Much Fewer Academic Philosophy Jobs Advertised This Season

Compared to previous years, the number of academic jobs advertised this season is much lower.

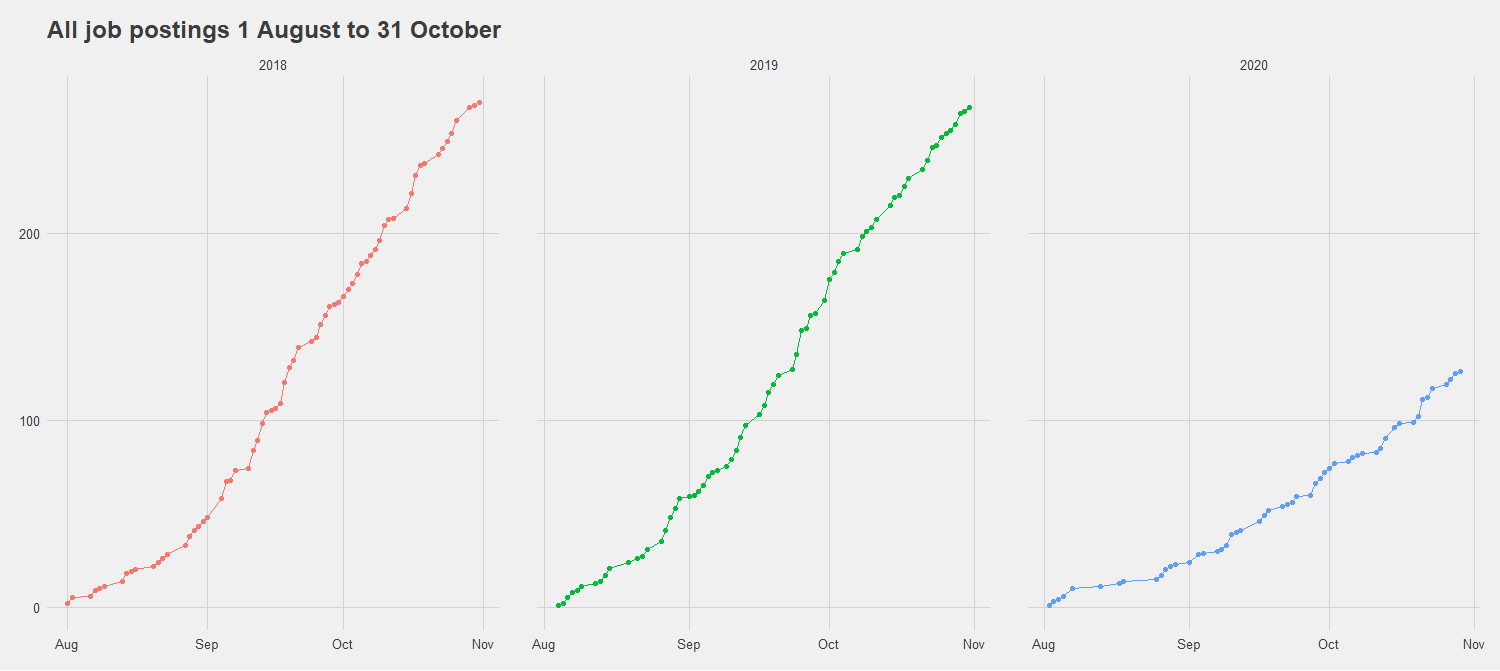

According to an analysis by Charles Lassiter (Gonzaga) posted at his blog, “there are 53% fewer jobs posted on PhilJobs in 2020 compared to 2018 and 2019.” By this time in 2018 there were 270 jobs posted, and in 2019 there were 267. This year: 126.

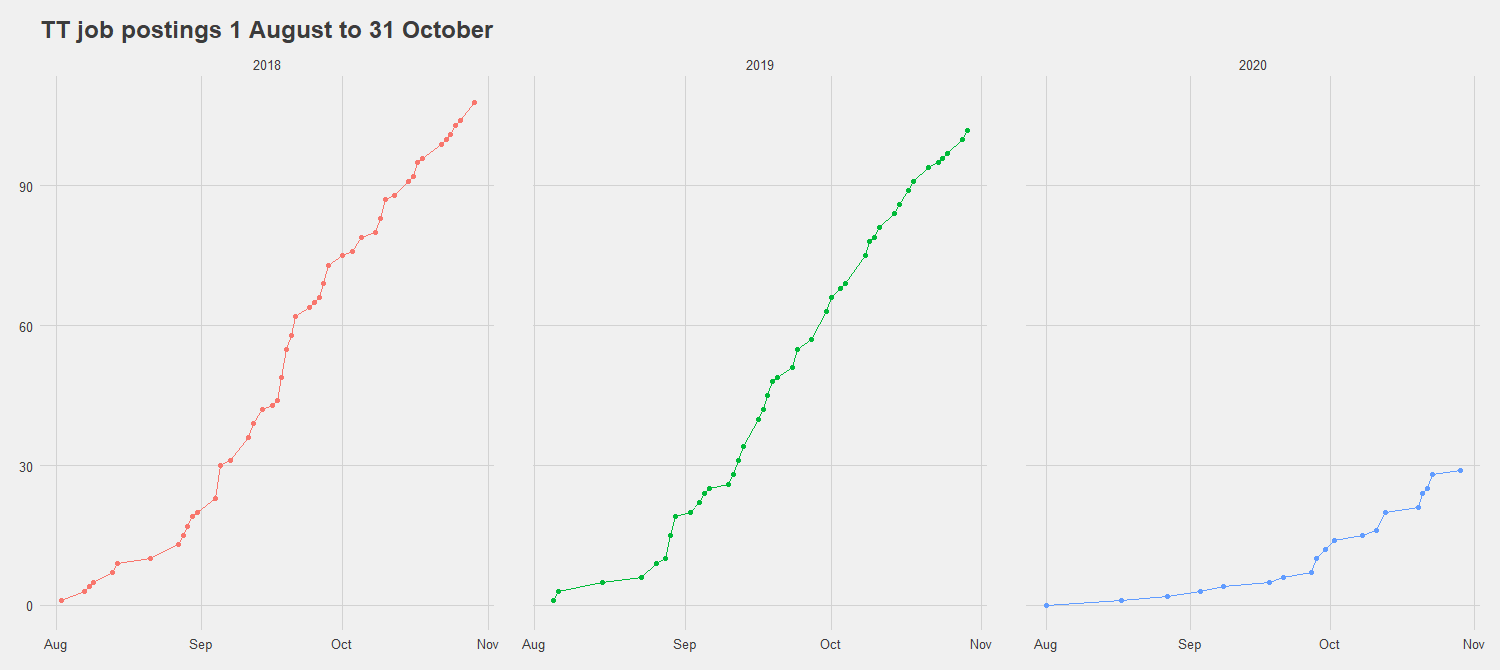

There was a 73% decline in advertisements for tenure-track positions this season, compared to last fall:

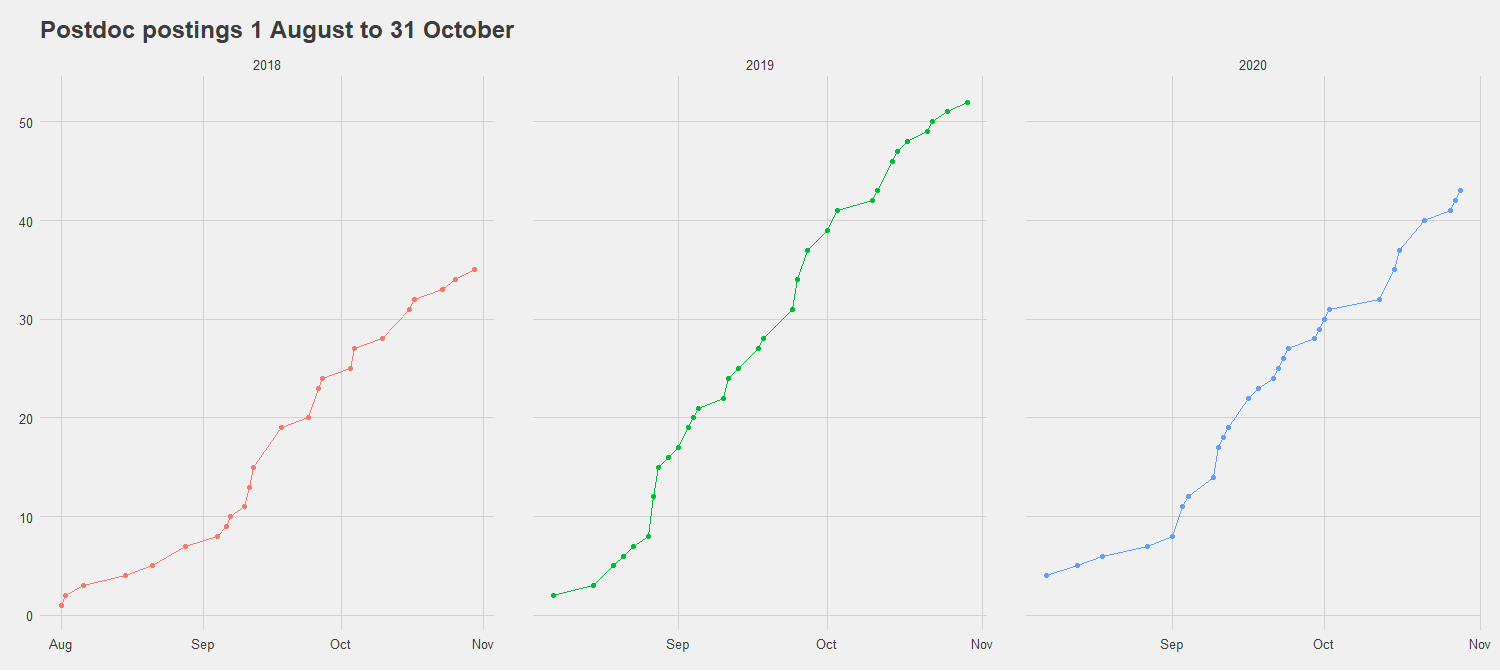

There hasn’t been much of a decline in post-doc positions, though:

Dr. Lassiter notes:

The long-term effects of this are hard to discern, but of this much we can be confident: there’s going to be a hell of a backlog of job-seekers for the foreseeable future. The job market wasn’t pretty before, and it’s only going to get worse. It’s not as though the jobs are going to spring back right away, if at all…. In light of this, I hope that departments and the APA increase their efforts to promote non-academic careers… The situation was already unsustainable, and the pandemic has only made matters worse. The profession can’t keep continuing to prioritize academic over non-academic careers. This is an opportunity to grow and adapt.

Related posts: Daily Nous Non-Academic Hires Page; Supporting Non-Academic Careers; Grad Programs and Non-Academic Careers; Duties to Graduate Students Pursuing Non-Academic Careers; Program Funds Non-Academic Internships for Philosophy PhD Students; New Site Interviews Philosophers With Non-Academic Careers; Profiles of Non-Academics with Philosophy Degrees; APA Issues New Guide For Philosophers Seeking Non-Academic Jobs

The shrinking academic jobs market coincides with what is predicted to be a significant shortage of k-12 teachers. I know it has already been a topic of conversation on this blog, but there is plenty of room to prepare philosophy PhDs for k-12 teaching and make k-12 teaching more attractive to someone who envisioned a career in higher education. On the point of preparation, there should be summer institutes that prepare PhDs in some of the basics of k-12 teaching and where pathways into the profession are described. If more PhDs choose k-12 teaching, interesting alternative pathways can be developed. On the point of attraction, concerned philosophers can do more to push the IB curriculum in schools. The IB curriculum leads to deeper learning for k-12 students, but it also puts philosophical thinking at the heart of secondary education. Finally–and this is likely far too idealistic on my part–philosophers can also push to make teaching conditions better in k-12 schools so that a PhD who chooses this path may still have time to pursue their intellectual interests and be rewarded for doing so by their k-12 district. And now this is being far too idealistic, but more students who get IB degrees may lead to a higher demand for philosophy in higher education, which could increase the need for academic philosophers.

I agree. I was a high school teacher (special education English and math), before I started my PhD and started looking back into it when my prospects for a college position looked bleak (I completed an “unranked” program in 2010 and didn’t have many viable prospects). I began preparing to get a math credential in a couple different states, when I lucked into a community college job.

I enjoyed high school teaching. I taught in a hard-to-staff school in South Central, Los Angeles. It wasn’t easy (I have some of the typical “war stories” people associate with inner-city education), but it was extremely rewarding. The school broke into “small learning communities” just after I left, one of which was Ethics, Leadership, and Mediation. They wanted classes to be themed along these lines. I was very tempted to stay to participate in that change, but felt the call of grad school too strongly. They also participated in the IB program you mention, but they were coveted jobs and typically went to senior teachers.

Though I adore my community college job and can’t imagine doing anything else for a living, I think I would have been very happy returning to high school teaching.

I agree with all the points you make about the value of philosophers in high schools. Though it takes work to earn the appropriate credentials, it is probably a great idea for many job seekers.

There needs to be a moratorium on _all_ philosophy departments admitting PhD students.

Here is a lengthy first draft, unedited post with some argument sketches in support of this claim:

As indicated above, there are far fewer jobs now than in the past. If there are not immediately fewer PhD students, then there will be the same number of job applicants for fewer jobs. So, there is guaranteed to be a group of people who worked to get a PhD but who cannot get jobs in philosophy.

Suppose we continue to produce PhDs at the normal rate. If hiring trends do not adjust upward dramatically, then each year there will be vastly more people with PhDs in philosophy seeking jobs than there are jobs available. So, the probability that those already on the job market will get jobs decreases accordingly.

Either those with PhDs but without jobs who are seeking jobs drop out, or they continue to live precariously as they seek permanent academic employment as philosophy profs. Those who drop out of the job hunt will have gone to great lengths (i) to get a PhD and (ii) to attempt to get an academic job, only to end up, usually just around the age of 30, having to start new careers, often with limited experience relative to their age cohort. Those who stay on the job market simply became part of an ever larger reserve army of un- and underemployed PhDs. This has very, very unwelcome effects.

First, consider more seriously those who get PhDs, don’t get jobs, and then drop out of the academic market to seek a new career. They will have spent the better part of a decade preparing for a career that they cannot have. The economic opportunity costs are massive. They have lost nearly a decade of earnings. They have lost nearly a decade of networking. They will have lost nearly a decade of making a home somewhere with good job prospects. Additionally, there are often huge emotional and psychological costs to spending nearly a decade training for a career, struggling to get a job in that field, and then having to abandon that project.

It is wildly irresponsible for even the “best” PhD-granting programs to create the conditions in which this terrible outcome is guaranteed. Even if only NYU and Princeton produce PhDs, these new PhDs still add to the competition faced by the older PhDs on the market. By increasing the competition for stable employment, the “best” programs increase the cost to older PhDs in precarious employment. And, even if the new PhDs are more likely to get jobs than the older PhDs, it remains the case that not all of them will get jobs. So, not only are departments negatively affecting the life chances of older PhDs, they are creating more bad outcomes by producing new PhDs who will not get jobs.

A caveat emptor rule for the person who freshly enters a grad program therefore fails to capture the negative externalities the production of new PhDs generates for the community of existing PhDs seeking jobs. For, while a new grad student may enter a PhD program with their eyes wide open to the likely failure they will experience on the job market, existing PhDs did NOT invite more competition onto the job market. Some of them may have entered their programs nearly 10 years ago (e.g., they got their PhD in 2016, have had a lengthy postdoc and an adjunct position or two). These people’s prospects are made significantly worse through no fault of their own when scores of new PhDs are granted each year.

So, it is a structural problem and not a problem of the aggregation of individual irresponsible acts committed by 22 year olds with dreams of being the next Haslanger or Scanlon. This problem can only be addressed by suspending all admissions to PhD programs for a number of years.

The remaining reasons to have a PhD program are mostly to benefit existing tenured professors. These professors benefit from teaching seminars to PhD students, where the professors work out their latest ideas. This is all well and good but it should not come at the cost of vulnerable people, namely, those who are unemployed or precariously employed in our academic community.

But, there is an additional well-known nefarious feature of PhD granting institutions.

Many PhD programs exist to produce casualized teaching and research labor. These people, nominally students but really mostly workers, do much of the teaching and marking that tenured professors do not want to do. As TAs, grad students lead sections, do the tedious labor of marking endless papers on the same few topics, and often filter the best students from the average students for tenured profs by meeting with the many many average students while gently nudging the best students to meet with the prof. Additionally, grad students sometimes teach their own classes. But, these are often service classes, such as intro this and intro that. This relieves tenured profs of this task, and allows them to teach lower enrolling but more interesting advanced classes. This is a good deal for colleges and departments because grad students are paid orders of magnitude less than profs. They also have no job security. So, it is a “good” economic deal for the department and the university.

Many schools are moving away from TA-heavy teaching. But, this is possible only because there is a reserve army of existing PhDs desperate for employment (see above). Once there are more people seeking adjunct jobs than there are adjunct jobs, PhD students can be relieved of all requirements to work since universities and departments can rely on the temporary employment of people with PhDs to do all the work once handed over to grad students. This dramatically limits the capacity for labor organizing – it’s much harder for adjuncts to get to know each other and there is little of the ‘natural’ solidarity that exists amongst grad students in the same department.

Nothing I’ve written here is news. I do think that it’s worth spelling it out over and over and over. And then we must ask: “Why are departments – any departments, from the Leiterriffic to the less Leiter-loved – still admitting PhD students?”

I can see no all things considered justification for this practice. It is, at the very least, directly contributory to a structural disadvantage of existing PhDs without jobs (and these people are often much more vulnerable than younger students entering grad school since the existing PhDs may have children). And at the very worst it is viciously exploitative.

There needs to be a total moratorium on admitting PhDs. Perhaps there should a full cycle moratorium, eg., six years.

Justin and I have disagreed about this in conversation. But now I’ll disagree with the internet! Sorry for typos and other infelicities of prose. I’ve not got the energy to edit this.

An immediate reaction I have to this is that the time lag between people entering PhD and gaining them is so long (sometimes ten years as you say!) that by the time your proposal would make a difference anyone currently on the market is likely to have either gotten a job or been forced out anyway. So it wouldn’t help the people you are concerned with. It might help people in the middle or towards the beginning of grad school know though. But another concern raised by the time lag is that we don’t actually know what the conditions for jobs will be like in 5-10 years time, so that by the time the proposal beings to take effect, it might have become unnecessary. A second worry is that it is anti-meritocratic: the same number of people who want jobs in philosophy will get them, but since there will be less of them from a particular age group, on average very slightly weaker philosophers than they would have been will get the jobs instead . (Note: this effect absolutely does not require the truth of ultra-naive views like the job market being a perfect meritocracy, or there always being a fact of the matter for any pair of individuals which of them is better at philosophy, it just requires some decent correlation between merit and job market performance, and that sometimes it is true that some people are better at philosophy than others-i.e. I am worse than the people I knew in grad school who seem to publish in Nous every six months for example.)

Why wouldn’t something akin to the Surgeon General’s warning on cigarettes be more appropriate than a total moratorium on admissions? Graduate admission letters could be sent with realistic probabilities of getting tenure-track, academic work. Certainly, many would still make choices contrary to their overall well-being, but I would think students prepared to begin graduate studies in philosophy are in a better position than most to make rational decisions about their futures.

If this kind of moratorium had been in place for my department in 2006, I would never gotten the chance to study philosophy at that level, and I think I would be the worse for it, regardless of my career trajectory.

Matt notes that those affected by today’s very bad job market are not just those going out on the market now, and those who will do so in the future, but those who entered the still-bad-but-not-quite-as-dreadful job market in previous years, and who did not know just how bad things would get. Even if their graduate programs told those in this latter group what the philosophy job market was like at the time they began their graduate studies, they were likely not given an accurate forecast so that they could really understand the conditions under which they’d later (that is, now) be seeking employment.

Matt’s point is important because it speaks to one element in my arguments against reducing the number of philosophy PhD programs, namely, that a better alternative to that is informing prospective and admitted students of their chances of finding secure employment in academic philosophy, so they know the risks they are taking. We can’t travel back in time and provide those currently competing in a crowded market for scarce jobs of the relevant information.

Matt takes from this point (and others) that we should not admit any new philosophy PhD students for several years. I disagree. I’ll admit that part of my disagreement comes from a general skepticism about top-down management of supply and demand, based on Hayekian knowledge-problem concerns and worries about unintended secondary, tertiary, etc., consequences. But more specifically:

1. Matt’s concern teaches us that we need to do a much better job in making clear and vivid to our prospective and admitted students just how bad the job market can be, so that they can be informed about what they are getting into.

2. While doing a much better job aiming for “informed consent” with our graduate students will not help those who are currently on the market, it is not clear that Matt’s proposed moratorium will, either. At best, we would start seeing effects from it 6 years from now, which will likely be too late. A moratorium might help those students who are just starting PhD programs now, but these are the same people who can be adequately informed. If there are two ways to possibly benefit someone, and one of those ways involves restricting their options, while the other does not, I tend to think there are several pro tanto reasons to favor the non-restrictive option. (These may be contingent reasons and epistemically “realistic” reasons but they’re reasons nonetheless.)

3. Matt’s reasoning does not mention the benefits of having more people study philosophy at the graduate level, but certainly they should be taken into account. (See my “Against Reducing The Number of Philosophy PhDs.”)

4. Even if Matt’s idea of a moratorium on admissions were a good idea, its success would depend on the cooperation of most philosophy PhD programs, with each acting against its own interests, and without the help of an overarching authority with teeth to enforce compliance or punish defectors. I hate to play the “unrealistic” card, but when it comes to assessing practical solutions to real-world problems, it’s important that the policy will actually achieve the desired end. Now it may be that a few high-profile departments can send a signal to others with their compliance to overcome this collective action problem, but I am skeptical that the signal would be sufficiently powerful to convert a sufficient number of departments. The opposing incentives are too strong.

5. By contrast, an information campaign is likely to face less obstacles. For one thing, much of the relevant information is not controlled by the departments, and more and more information is available at various places online (for example), and can be further publicized. For another, to the extent to which the relevant information is controlled by departments—such as a department’s placements and placement rates—we have seen success in pressuring for disclosure. Additionally, there is the possibility of a name-and-shame approach to departments that do not adequately caution their students.

6. What are the costs of Matt’s proposal, besides reduced opportunities for those who want to get a PhD in philosophy? (a) One worry is a possible temporary reduction in jobs advertised, as departments complying with a moratorium may find themselves unable to get their administration on board with new or replacement hires while the moratorium is in effect. (b) Another worry is long term: status quo bias is strong, and departments might rightfully be worried that after five years of not admitting students, to have to re-make the case for having a PhD program to a budget-conscious administration is too high-risk. Further, the permanent loss of graduate programs would almost certainly negatively affect the number of hires affected departments could make.

7. If we do a much better job at providing the relevant information about job prospects to our students, early on and repeatedly, it will likely still be the case that there are more applicants for academic philosophy jobs than there are jobs. But, again, it is not clear that the best way to address that problem is by reducing the opportunities for graduate study in philosophy. It could be that being more serious about non-academic job training, as many have suggested, is a better approach. Again, the idea here is to provide information and opportunities, rather than limit them.

Perhaps, in addition to informing new students about market conditions, departments could create and promote dual certificates or degrees that prepare students for non-academic fields as fall-backs. There are already many PhD/JD programs (e.g. at Georgetown, Penn, Stanford, etc.). Perhaps, philosophy departments could work with computer science departments for joint certificate programs like a PhD/programming certificate (Harvard offers a 4-course certificate: https://www.extension.harvard.edu/academics/professional-graduate-certificates/programming-certificate), or with education departments for PhD/teaching credential programs.

A moratorium seems like an extremely radical step, before at least trying less disruptive ones first.

Wouldn’t the moratorium mandate the hiring of more faculty? I taught a number of classes as a graduate student, and graded for many more. That labor will have to be done by someone. (Although I should note that my per-hour compensation was much better as a grad student than as an adjunct).

At Texas A&M, university funding for graduate programs is proportional to the average number of students that were enrolled in the program over the previous three years. A moratorium on admissions is, under these conditions, a decision to permanently cut the size of the PhD program (or to end it, if it lasts for a few years). (The rule only counts students in the first five years of a PhD program towards the total, and university funding can only be used for students in years 1-5, so there is no way to make up for this by retaining current students longer to insulate them from the job market.) (It may be that, all things considered, shrinking or ending our PhD program is the right move, but different considerations need to be brought to bear for that than the considerations that might motivate a moratorium with a planned return to full size.) I expect that many departments operate under constraints that have some of these features.

Quite separately, I think there’s a concern about a universal moratorium on graduate admissions. This may be what is best for current and recent past PhD students, but it comes at a large cost to the people in upcoming cohorts for whom a PhD would be a good move. A drastic shrinking of the pool of PhD program enrollments might allow these individuals to still find a place, but a complete closure dislocates the career plans of many just as much as a glut does to others.

I’d love to see a discussion on DN about the ethics of (1) tenure-track profs entering the job market right now, and (2) departments who hire those persons. It’s a complex issue and I don’t wish to pass too much judgment on individual applicants, but surely there are strong ethical reasons to prioritize the hiring of people whose careers and lives will be destroyed by all of this: Grad students, maybe expiring postdocs, etc. And unlike previous years, it is decidedly *not* the case that departing tenure-track professors are simply opening up a line for hiring next year; admins will use every departure they can to trim costs and shut down lines. I do hope that hiring departments will at least have this discussion; I would be proud to be a member of a profession that collectively decided, at this crucial moment, to try and protect some of its most vulnerable members by making sure that those 30-35 TT positions go primarily to grad students.

Moreover, one reason to avoid PhD admissions that M.Smith above doesn’t highlight is that it immediately frees up funding to shelter late-career grad students by extending their degree time. I think that this is clearly a moral imperative: departments should be doing everything they can to give their later-year students employment options, and extending the stipend and teaching duties seems like an obvious goal. I urge everyone to raise something like this possibility with their departments in the coming year: cut the grad admissions in half, try to convince the admins to use the savings to shelter the grads you already have.

I am a strong advocate within my graduate program for cutting admissions and trying to redirect some of that funding to extend support for current students. As I mentioned in a comment above, university rules normally prohibit the use of any of this funding for students who have already completed 5 years of a PhD (we usually use a small pool of unrestricted money to pay for minimal enrollment of 6th year students, but not beyond). The university has made some statements about leniency for students impacted by the pandemic that we are trying to use to enable the diversion of some funds to sixth or seventh year students in the near future, but university policies may not end up allowing it.

I don’t think it’s a good idea for hiring committee to second guess the motive (and the morality of the motive) behind an applicant’s job application! I see the good intention, but that seems to be over manipulating. There are so many reason a TT faculty may apply for jobs. Not to mention that there are so many program cuts looming over the horizon — including my own program — as we saw in the other post. And TT faculty typically can’t apply to post-docs. I think hiring committees just don’t have the information required to make that moral judgment for people.

Derek, this has nothing to do with moral judgment. If you have $100 and you can give it to either (1) someone you know is starving, or (2) someone who only might be starving but who might not be, you give it to the first person, and your doing so does *not* in any way rest on the judgment that the second person is feigning need. This is just a numbers game. If a grad student is hireable in a search, I think departments should prioritize them over a TT-faculty, unless of course there are strong positive reasons to think that the TT-faculty is also in dire need (i.e. their department was just shut down).

Kenny, you’re right of course, but I have to say that as the years roll on I tire of the “university rules don’t allow it” justification for allowing grad students to get slaughtered on an increasingly poor job market. We are the ones who can lobby to have the rules changed, and so we should.

Was PhilJobs well enough established in 2008 and 2009 to enable any comparison of the current drop with the drop around the global financial crisis? My recollection is that data then were still focusing on Jobs for Philosophers, but it would be good if anyone has those numbers available (or information on whether the transition from Jobs for Philosophers to PhilJobs made it hard to interpret *any* numbers around that time).

Sadly, PhilJobs wasn’t well enough established in 2008-2009 to make any meaningful comparisons to now. The earliest data available on PhilJobs is 2011. If memory serves, I was getting my JFP in the mail during the financial crisis.

Something that I think is worth getting proper data on: Anecdotally, I’ve seen a *huge* drop-off in jobs of any sort in the US this year, even postdocs. European/Asian job listings are keeping the numbers from being near-zero, it has seemed to me; the vast majority of postdocs seem to be in Europe this year. I would be very interested in seeing graphs of this sort broken down by region (especially North America/Europe/Asia postings), if anyone cares to do that work.

Hi Market-Goer, I just did a quick count for postdocs advertised on PhilJobs for 2020 and here’s the regional breakdown:

Asia: 2 (one in China, the other in Israel)

Canada: 4

Europe (including the UK): 12

US: 25

…out of 43 total.

I know PhilJobs advertises jobs largely in Canada and the US, so if there are other sites for posting jobs in Europe or Asia, I’d love to know and look at some of their postings too.

Ah, I see it’s actually easy to search for old postings on philjobs; I didn’t realize you could set the search date back in the past that far. So here’s some of my own findings, using the same dates as Lassiter’s blog post did (this gave me slightly different numbers than you have):

Postdoc listings, by world region:

August 1st 2019-October 31st 2019: 44 NA, 8 Europe, 0 Asia (one in Rotterdam that’s misclaffied on Philjobs as “Asia” I have moved to Europe), 52 Total

August 1st 2020-October 31 2020: 28 NA, 11 Europe, 3 Asia, 42 Total

So my anecdotal sense does have something going for it: the European postdoc listings have *increased* across these two time periods, while the NA postings have dropped almost in half (and a few Asian postdocs are also pulling the total up — there are actually two Israeli postdocs listed in this period, one in Jerusalem and one in Haifa; my suspicion is that most Asian postdocs simply aren’t advertised on philjobs, and I know some of my colleagues have taken postdocs in China found through more obscure channels). The overall number of postdocs is also lower than in 2019, but I’d need to do more data-diving to see if 2019 was representative or not.

So here’s some older data, also by region, with the same August-October dates to make the data uniform:

2018: 30 NA, 3 Europe, 0 Asia, 33 Total

2017: 32 NA, 8 Europe, 1 Asia, 41 Total

2016: 29 NA, 7 Europe, 1 Asia, 37 Total

2015: 39 NA, 9 Europe, 0 Asia (4 “Asia” misclassified, I have moved them all to NA), 48 Total

2014: 20 NA, 3 Europe, 1 Asia, 24 Total

2013: 26 NA, 6 Europe, 1 Asia, 33 Total

2012: 29 NA, 36(!) Europe, 2 Asia, 67 Total

2011: 18 NA, 3 Europe, 0 Asia, 21 Total

So 2019 *does* look like an outlier in the total number of postdocs (especially NA postdocs), and Lassiter is right that the overall picture looks similar between this year and 2019-2013. The 2012 numbers are wild enough on the European front that I really wonder whether philjobs is an accurate picture of the EU scene, though: all of the listings there are genuinely UK or European job listings for postdocs posted in that time period, so it doesn’t look like a coding error, but I have no other ideas for how to make sense of it. The EU numbers in general are all over the place, looking at this: the 11 this year is higher than any year except 2012, while in the period I looked at they had three years with a meagre 3 postdocs advertised on philjobs. I’ve not been looking to work in Europe, so perhaps someone more familiar with the European job market can clarify whether these postdoc figures are accurate.

European jobs are usually advertised on a hodgepodge of national and international websites and mailing lists; it’s basically impossible to get a comprehensive picture. PHILOS-L is a good starting point, as is jobs.ac.uk and (for the German/Austrian/Swiss market in particular) the academic job ads on zeit.de .

I would also expect more European postdocs being advertised come springtime, when this year’s ERC grant money is turned into jobs.

Matt suggests a moratorium on admitting graduate students, but another option of opening available jobs for newly minted PhDs is a mandatory retirement age. Why cull the bottom, when we could shave off the top?

Apparently, a major impediment to retirement that is ripe for mitigation is the presumed change in day-to-day lifestyle (e.g., a ticket to Florida and mandatory plaid golfing pants). However, it seems that the change in a professor’s life from “going emeritus” need not be anything more than no longer doing (much) formal teaching (or bureaucratic labor). That is, professors could keep their office and come into the department, serve on committees, and publish as much as they’d like. Apparently, keeping one’s office is crucial. It might create an office space “crisis” for new hires, but that’s certainly preferable to a job market crisis.

https://www.chronicle.com/article/a-professors-last-crucial-decision-when-to-retire/?cid=gen_sign_in

I believe that in the U.S. the Age Discrimination in Employment Act bars mandatory retirement ages (with presumably exceptions for a few specific occupations, e.g. airline pilots). Or if it doesn’t actually bar them, it’s had the effect of making them much less common. Before the ADEA mandatory retirement ages for professors were pretty standard, I think; not now.

I think it’s important to note that not all jobs in philosophy are listed on philjobs. Most community college jobs are not and more than a few teaching focused SLAC positions aren’t there either. As a theoretical issue this isn’t too important to the point this post makes. Even if you factor in the community college jobs that are out there on other sites the market still looks bleak. However, community college jobs are often posted later than others (January or after seems pretty typical). So there still might be some change.

The practical point is more important though. If you’re interested in teaching focused jobs you simply can’t limit yourself to philjobs. At the very least check the listings on higheredjobs.com. And keep a look out for jobs late in the cycle.

One other thing I’d add: I wonder if there might not be a boomlet of jobs later in the cycle for both 2 and 4 year colleges. The COVID recession has decimated state budgets so many colleges are no doubt worried about cuts. But if Biden wins and the Democrats take the Senate I’d bet any amount of money you choose that they will provide budget assistance to states. A COVID vaccine– and there’s a pretty good chance we’ll have one by the end of the year– would also do a lot to clear up uncertainty about the fall 2021 semester enrollments, which is also a factor in the low rate of hiring. I’m not optimistic enough to think we’ll get a huge boom of hiring late in the season that redeems this awful year, but I would expect a fair amount of VAP hiring to fill needed teaching positions for fall 2021. But maybe I’m being too optimistic.

On thing we have to be honest about is just how long PhD education takes these days.

If job seekers lose 3 years it’s one thing, if it’s a decade its quite another.

This suggests that we have to do everything to remove things that are nice but not essential, including:

1. Teaching. This has been already discussed. No teaching. It just isn’t fair to have people doing service until they have a job.

2. Coursework. The CVs these days have an inordinate amount of postgrad coursework. One or two courses max.

3. PhD as book: Move to 3 papers model.

In 3 years someone can take a course or two, and write 3 good papers. That should be enough.

Then we have to be honest at this point, and have an up or out policy.

We’re not being kind, but cruel, by postponing this decision unnecessarily for another 5-7 years.

It’s a desperately sad situation, but one that only gets worse (not better) by prolonging.

If you exclude jobs related to (a) AI ethics and (b) philosophy of race, I would estimate the number of TT positions advertised further dwindles by two thirds. I’m not necessarily complaining; in fact, I work in one of those areas. But those who are not watching the job boards closely should know that, for the modal philosophy candidate, this year looks much bleaker even than the numbers in this post would lead one to believe.

Josh above (reply would not work)–

My whole department was essentially closed by threats of increased teaching/travel/etc or taking a separation-enhanced early retirement. For me it only advanced retirement a year or so–for others it forced their hands. What I wonder is how many such forced retirements are occurring across the country. And you can guess how many junior positions this produced–a handful of pitifully paid lecturers at best.

My guess is that even a large number of early retirements is no good indicator of increasing hiring prospects, especially tenured positions. Negative politics and the pandemic is a one-two punch that the discipline will endure with only diminished power and numbers by any scenario I can see,