An Empirical Approach to the Analytic-Continental Divide

What’s the difference between analytic philosophy and Continental philosophy? In a new paper, a pair of researchers use a computer analysis of the content of different journals to test one way the distinction is sometimes characterized.

Moti Mizrahi (Florida Institute of Technology) and Mike Dickinson (Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) note that sometimes the distinction between analytic philosophy (AP) and Continental philosophy (CP) has been drawn by reference to a supposed difference in the importance of argumentation in these philosophical traditions. In their “The analytic-continental divide in practice: an empirical study,” published in Metaphilosophy, they write:

Some philosophers have argued that the differences between AP and CP have to do with the place of argument in these two philosophical traditions or camps. That is, it has been argued that argument occupies a more important place in AP than in CP.

They then engage in an interesting attempt to use digital humanities methods to test whether the different philosophical traditions differ in the degree and type of argumentation they use.

They first identify “indicator words” that tend to correlate with (but, they acknowledge, do not guarantee) the presence of particular kinds of arguments. For example:

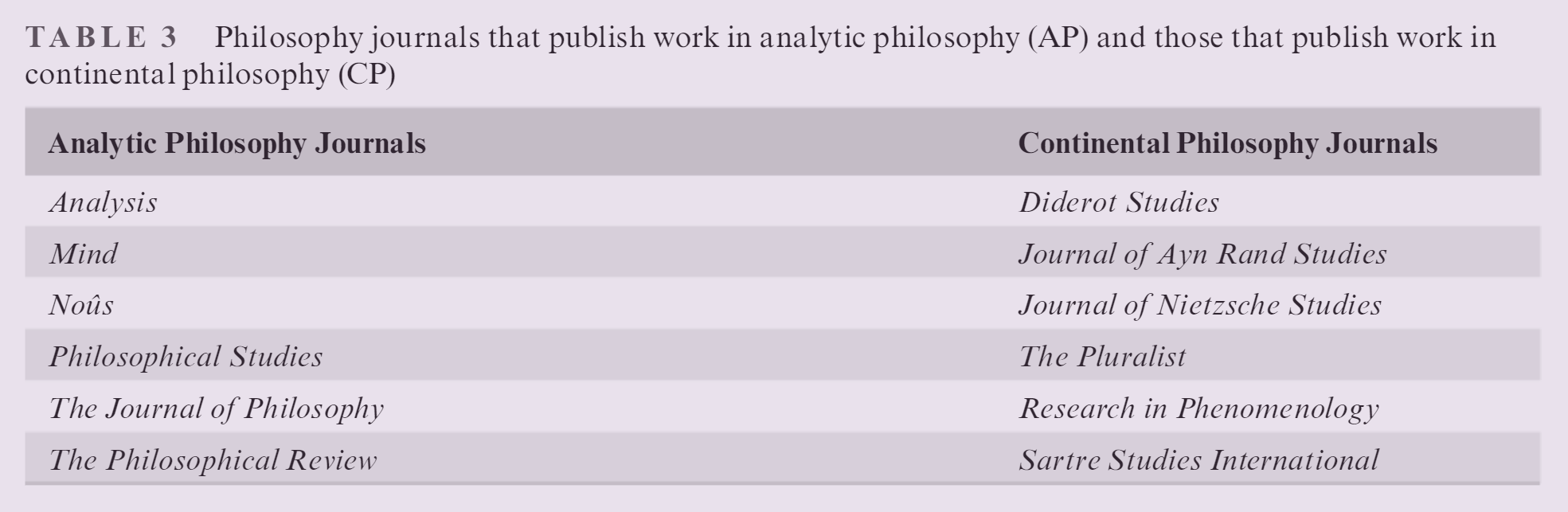

Then, they selected a set of journals they identified as largely publishing analytic philosophy and a set of journals they identified as largely publishing Continental philosophy, and used a combination of text-mining programs to run several kinds of searches for the indicator words.

What did they find?

Our results suggest that articles published in both AP journals and CP journals contain arguments. Moreover, our data reveal no significant differences between the types of arguments advanced in articles published in AP journals and the types of arguments advanced in articles published in CP journals. In fact, both AP and CP journal articles contain the three types of arguments we have looked at, namely, deductive arguments, inductive arguments, and abductive arguments, with no significant differences in frequency.

Mizrahi and Dickinson ran their study on just 12 journals (see table 3, below), so it would be good to run this study with a larger set:

As others have noted (on social media), the selection of representative Continental philosophy journals seems strange: The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies is rather fringe in academic philosophy, The Pluralist is the official journal of the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy, and neither Randianism or American Philosophy are known as kinds of Continental philosophy.

Still, the method that Mizrahi and Dickinson employ here is interesting for its potential to correct distorted or false stereotypes of methods, styles, and areas of inquiry in philosophy (not just in regard to the analytic-Continental divide, but in regards to philosophy across different cultures, or, as the authors note, across different subfields of philosophy). And since such stereotypes sometimes constitute obstacles to learning, collaboration, and opportunity, there may be practical as well as intellectual benefits to be had from the method’s development.

(via Eric Schleisser)

Related: The Methods of Analytic Philosophy, How Journal Capture Led to the Dominance of Analytic Philosophy in the U.S., Thoughts about the Analytic-Continental Distinction, Collingwood and the Contintental – Analytic Divide, The Origins of Analytic Philosophy, The Flaws In Analytic And Continental Philosophy, The “Analytic Co-opting” and Death of the Continental Tradition

I’m not sure whether the authors have established their conclusion or provided further evidence for the limitations of text-mining methods.

i’m sure they haven’t even come close, ignores context/grammar, some irony in trying to evaluate continental philo this way.

maybe more helpful would be a more genealogical approach:

https://newbooksnetwork.com/the-dialogical-roots-of-deduction

Indeed one commonly finds deductive arguments in continental philosophy. Here is, for instance, Derrida, employing the classical derivation rule ex falso quodlibet:

And yet I think this fragment could be, with some charity, construed as a deductive argument:

In order to forgive, one must forgive the unforgivable.

(One kind of action usually deemed as) forgiving does not forgive the unforgivable.

(That kind of action thought of as) forgiving is not actually forgiving.

Derrida’s love for paradox should not obscure the fact the there is argument involved. However, I also think that this example points to a limitation in the method of text mining used. Maybe it is not the presence or absence of textual markers of argument that separates AP and CP, but a whole attitude towards language and argument.

It seems clear to me that part of what Derrida is doing in that paragraph is presenting a paradox, and this is a style of doing philosophy he clearly values. Why would he value that? How does argument work alongside this style?

“Maybe it is not the presence or absence of textual markers of argument that separates AP and CP, but a whole attitude towards language and argument.” that’s pretty explicit in someone like Derrida as is the performative aspect of his work, maybe also in someone like Wittgenstein tho I tread lightly around the ongoing interpretive wars in his name, also see: https://jcrt.org/archives/12.2/dickinson.pdf

Indeed it is a deductive argument—that’s the point. Also I think it’s pretty clear that “In order to forgive, one must forgive the unforgivable” is the conclusion of that argument.

But why should anyone accept the premise of the argument, i.e, that you can’t forgive something forgivable? To my mind a more analytically inclined philosopher wouldn’t give an argument, deductive or not, with that kind of premise.

Yes, I agree. I wasn’t implying it was a good deductive argument.

Here is something to think about. I self-identify as an analytic philosopher–I was primarily trained in analytic philosophy–but I publish work on Continental figures like Nietzsche. I would argue that journals like the Journal of Nietzsche Studies, with which I’m most familiar, is much more of an “analytic” journal than a place to find Continental thought. I think it’s clear that both AP and CP use arguments. But the style, presentation, or mode of delivery between AP and CP is often very different, and I’m not sure how digital humanities work might illuminate that difference. Personally, I often have a hard time clearly understanding what’s going on when reading authors deeply entrenched in Continental philosophy–even when reading work on thinkers like Nietzsche that I know pretty well–whereas it’s much easier for me to understand analytic treatments of Continental thinkers. And when I present work at Continental conferences, I sometimes find the audience pushing back against my analytic style more than any arguments I’ve given, which again suggests that the “divide” is elsewhere.

The editorial board for the Journal of Nietzsche Studies supports your idea that it is problematic to regard it as exclusively / primarily publishing “continental philosophy.” It seems like the authors did not put too much thought into what prima facie distinguishes the two.

coming from the other side of the divide I find that there is a often something akin to misplaced-concreteness to analytic projects in that they often assume that social doings have the kind of uniformity/generalizability that one doesn’t find in ‘thick’ studies of how things actually play out (the kinds say that pragmatist/realist studies of judgments by judges show us), the same sort of logic that seems to lead people to do these kinds of searches/studies without much (if any) wrestling with how they set up the categories/frames to place words/images in as data which can be treated with/like numbers. For Heideggerians (writ large) this kind of calculative reasoning is suspect, for better and worse I’m sure.

A lot of my background is in the “pluralism but in the spirit of Analytic philosophy” approach. I think there’s a grain of truth to the idea that CP is less straightforwardly argumentative.

I also think there’s a grain of truth to the idea that one of the biggest differences between CP and AP is stylistic.

That’s why the biggest problem I have with the method used in this paper is that the arguments in a lot of CP require some interpretive effort to unearth and it’s rare to see someone from that tradition using phrases like “thus necessarily” or any of the other indicators.

I like the idea of using computers to analyze texts but one of the challenges, I suspect, will be that people who are squarely within AP are closer to being on the same page when it comes to how they express their views, frequently using phrases like the indicators used in the paper, while people who are squarely within CP are often self-consciously trying to express their views in unique ways.

Lots of questions about all of this.

I don’t have access to the full paper at the moment, but does anyone know whether their study was run on the same number of words (approximately) for each category?

It’s probably not good enough that the same number of journals or papers were given for each side, if that’s even the case. It could be (I’m guessing/making this up) that Continental papers are more verbose than analytic papers; if so, then the results would naturally skew in favor of Continental because of its larger sample size, if the word count wasn’t controlled.

Unless they’ve left it out of the methods section of the paper, there is no attempt to balance the size of the corpus in each condition to account for the length of papers, or number of papers per year, or anything like that. They do calculate the key results in terms of the ratio of articles containing the relevant indicator words to total articles in the journal, so accounting for those differences in a sense, but they don’t attempt to balance for them.

For two related problems, consider the journal Diderot Studies. Many of the articles in the journal are published in French. As far as I can tell, they only text-mined these articles for English terms. There is no statement about excluding non-English articles or whether their is even metadata for which they could do that. So is that biasing the ratio for Diderot Studies? Also, Diderot Studies appears to have been discontinued in 2015. The authors don’t give the data range for their corpus of journal articles. Does that make the number of articles between the two conditions even more unbalanced?

If we ask the question of place with respect to CP, where does fit on the spectrum between fiction and non-fiction? Lots of work has been done in AP to understand this distinction. For example, we can say Thus Spoke… is a work of fiction. We can say of ‘Is JTB Knowledge?’ that it is a work of non-fiction. But what can we say about ‘Beyond Good and Evil’? What can we say about ‘Fear and Trembling’? What can we say about ‘Phenomenology of Spirit’ or ‘Being and Time’? And the same with the dialogues. CP really complicates the fiction non-fiction distinction. It isn’t clear what it is. Maybe it is a separate category of fiction? Is it non-fiction? Does it contain facts? AP may also lack facts and be highly speculative, as well. But it presents the knowledge with less prejudice towards its conclusion.

I like to think of the distinction in terms of the good. CP wants to continue the Platonic project of asking what the good life is. AP is uninterested in that. AP what’s to know what counts for meaning.

This is something of a ‘shoulda woulda coulda’ detail but I think the way the mining has been set-up is a bit lackluster (and potentially undermines part of their conclusion).

They write: “Applied in this manner, the string_detect() function will return a list of true or false logical values, where true indicates the presence of the argument indicator and the anchor at least one time within each document and false indicates no pattern match.” (emphasis mine)

I worry that this induces a bias for texts which are less uniform in their use of the signal words for particular argument-types.

If I understand them correctly; if a single set of signal words is used very often within a single text, it will be counted as only a single hit.

They then, for such a single text, look how many of their chosen signal words were found out of the total they are checking for – the more types are found, the more ‘deductive’, ‘inductive’, etc. the text becomes.

But, this means that if the abductive indicator-words simply contain many pairs of words that are never used (because, perhaps, they are linguistically superfluous) and only pick words from half of that list, this sort of argument-type will structurally score lower whereas there might have been quite many abductive argument indicator-words in the texts (just less diverse).

Second worry I have is that without finding an ‘argument density’ say, per word for example (and not per article preferably, for reasons Patrick Lin reacted with here as well), but only extracting ratios of types of arguments, they don’t answer the question they open with: does one type of text use more arguments than the other kind of text generally does?

Still, I think this is super cool study, and it is an interesting and valuable idea to see if one can find and check ‘general statements’ about bodies of texts in this way, but I wonder why they didn’t just count all the occurrences of all of the indicator word-pairs in the texts. Dividing by the total number of words investigated could even have given them an idea of the ‘argument density’!

This would have allowed them to 1) compare AP en CP journals in total averaged amount of such indicator words and 2) be less sensitive to biases introduced by their choice for specific indicator-words.

In addition to the problems raised with the Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, The Pluralist, the Journal of Nietzsche Studies, and Diderot Studies in other comments, it seems worth mentioning that Sartre Studies International has many articles in it that aren’t philosophy at all, but rather literary studies of Sartre’s plays and novels, historical or biographical studies of Sartre’s life and political work. The journal describes itself as “a peer-reviewed scholarly journal which publishes articles of a multidisciplinary, cross-cultural and international character reflecting the full range and complexity of Sartre’s own work. It focuses on the philosophical, literary and political issues originating in existentialism, and explores the continuing vitality of existentialist and Sartrean ideas in contemporary society and culture.” Also, this journal publishes articles in French, though seemingly fewer than Diderot Studies.

It seems like the only journal whose inclusion as “continental philosophy” is unproblematic is Research in Phenomenology.

Almost all of the markers are for conclusions. “The bigger the burger, the better the burger. The burgers are bigger at Burger King” would thus not pass muster as an argument.