An Accessible and User-Friendly Argument Mapping App (guest post)

“Argument mapping is about twice as effective at improving student critical thinking as other methods,” writes Jonathan Surovell (Texas State University). However, “there are obstacles preventing philosophy teachers from adopting it.”

“Argument mapping is about twice as effective at improving student critical thinking as other methods,” writes Jonathan Surovell (Texas State University). However, “there are obstacles preventing philosophy teachers from adopting it.”

In the following guest post, Dr. Surovell discusses argument mapping and its benefits, and introduces us a new app for teaching and learning it, Argumentation.io, that is user-friendly and meets accessibility standards.

Argumentation.io:

An Accessible and User-Friendly

Argument Mapping App

by Jonathan Surovell

The more we learn about teaching argument mapping (sometimes known as argument diagramming or argument visualization), the more remarkable its benefits to students seem to be. Unfortunately, there are obstacles preventing philosophy teachers from adopting it. One of these obstacles is that, up until now, it’s been virtually impossible to teach argument mapping consistently with university accessibility standards. Over the past couple of years, my team and I have developed a new web-based app, Argumentation.io, that, we believe, will solve this problem while making argument mapping more intuitive and effective for all students. We’ll soon bundle the app with other materials that will make it easier for instructors to start teaching a fully accessible argument mapping course.

Argument Mapping

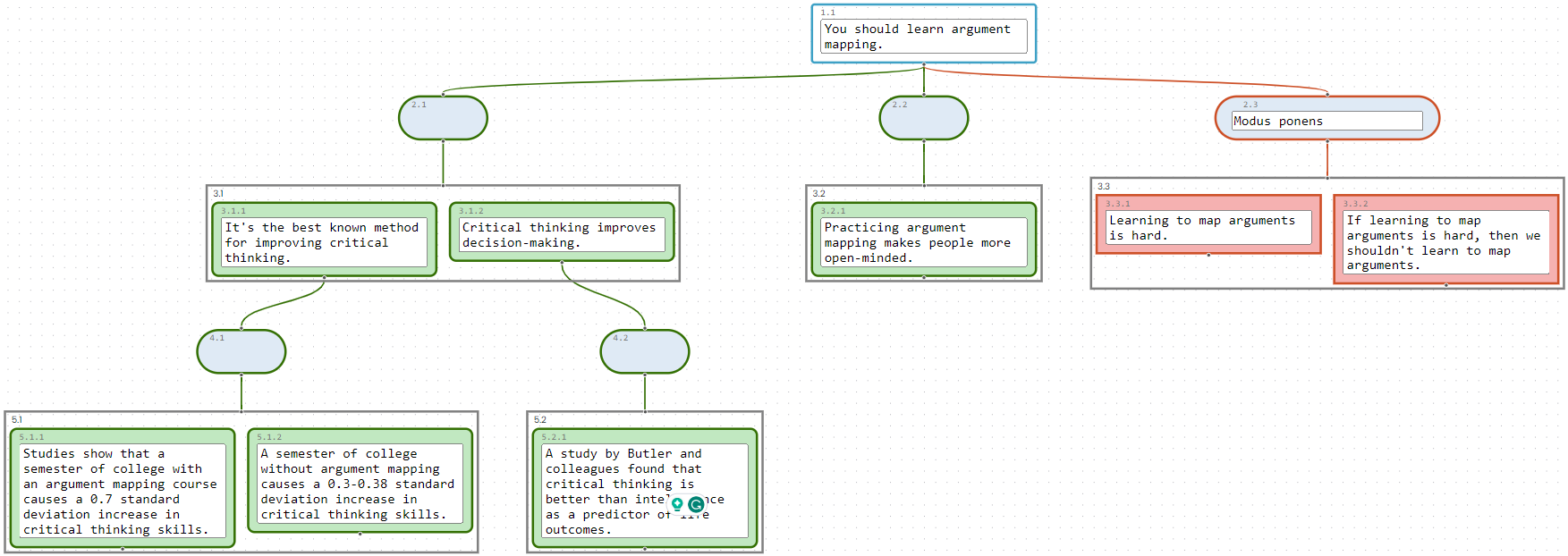

An argument map is a diagrammatic representation of an argument in which statements go in boxes and logical relationships are conveyed by the shapes and colors of these boxes and lines connecting them. Argument maps allow for the simultaneous presentation of reasons for and objections to a given claim, and so can perspicaciously convey multiple sides of an issue. Here’s an example:

Here’s a link to this example at argumentation.io.

Argument mapping is often taught in introductory philosophy courses that include a critical thinking component. I use it for the first five or six weeks of my “Philosophy and Critical Thinking” and “Ethics and Society” courses at Texas State University. My students and I then map the philosophical articles we spend the rest of the semester reading. Argument mapping is also taught in pure critical thinking courses and in various courses outside of philosophy.

Argument mapping is about twice as effective at improving student critical thinking as other methods:

| Course Type | Size of effect on critical thinking (standard deviations) |

| A year of college with the courses unspecified | 0.16 over the course of a year |

| A semester of college with a mixed philosophy and critical thinking course | 0.38 |

| A semester of college with an argument mapping course | 0.7–0.71 |

Its effect is statistically “large,” whereas other teaching methods’ effects are “small” to just barely “moderate.”

Eftekhari and colleages (2016) found that courses that use a computer-based argument mapping app are more effective than those in which students map with pencil and paper. Dwyer and colleagues (2012) found that argument mapping retains its efficacy in online courses.

Argument mapping courses may also lead to:

- “[M]ore deliberate and fair-minded approaches to understanding” contentious issues and interpersonal challenges,

- Better essay writing (see here and here),

- Better scientific reasoning,

- Better mathematical reasoning, and

- Better recall of course content.

Why is argument mapping so effective? Some hypotheses:

- It involves dual visual-propositional modalities, which frees up memory for understanding logical relationships.

- The use of Gestalt grouping principles improves understanding and processing.

- Hierarchical ordering helps content enter into, and stay in, memory.

- Argument mapping is particularly amenable to scaffolding–typically, students learn one aspect of mapping at a time, starting with reasons and objections, followed by (not necessarily in this order) co-premises, independent arguments, sub-contentions (intermediate conclusions), and inference arguments.

Argumentation.io

Despite these impressive benefits, argument mapping isn’t widely used in higher education. Why? Presumably, lack of awareness plays a role.

There are two other likely factors. One is accessibility. Most colleges and universities require their courses to be accessible to students with disabilities. In fact, Section 508 of the American Rehabilitation Act legally requires most universities to make their courses accessible. But because argument maps are diagrammatic, and not purely text-based, a blind person can’t create an argument in a word processor (or with a pencil and paper), nor are existing argument mapping apps accessible to the blind.

Argumentation.io solves this problem. All the functions in our app are screen reader and key command compatible—even drag and drop editing. Instructors can use the app as their standard argument mapping app, for purposes of instruction and demonstration, without worrying about violating a student’s civil rights.

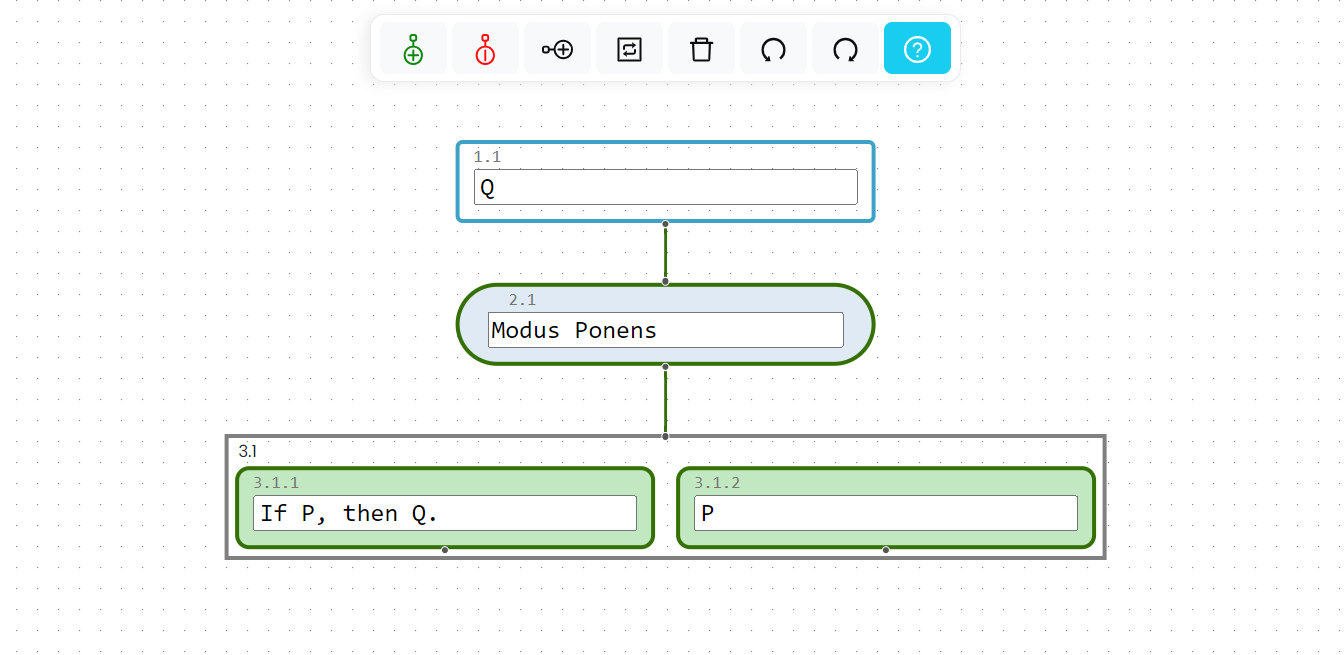

Another novel feature of Argumentation.io is its use of inference boxes: whenever a user adds a reason or objection to their map, a box representing the inference is automatically placed between the reason/objection and the claim it supports/opposes. In this map, box 2.1 is the inference box:

Example with ‘modus ponens’ in the inference box (box 2.1).

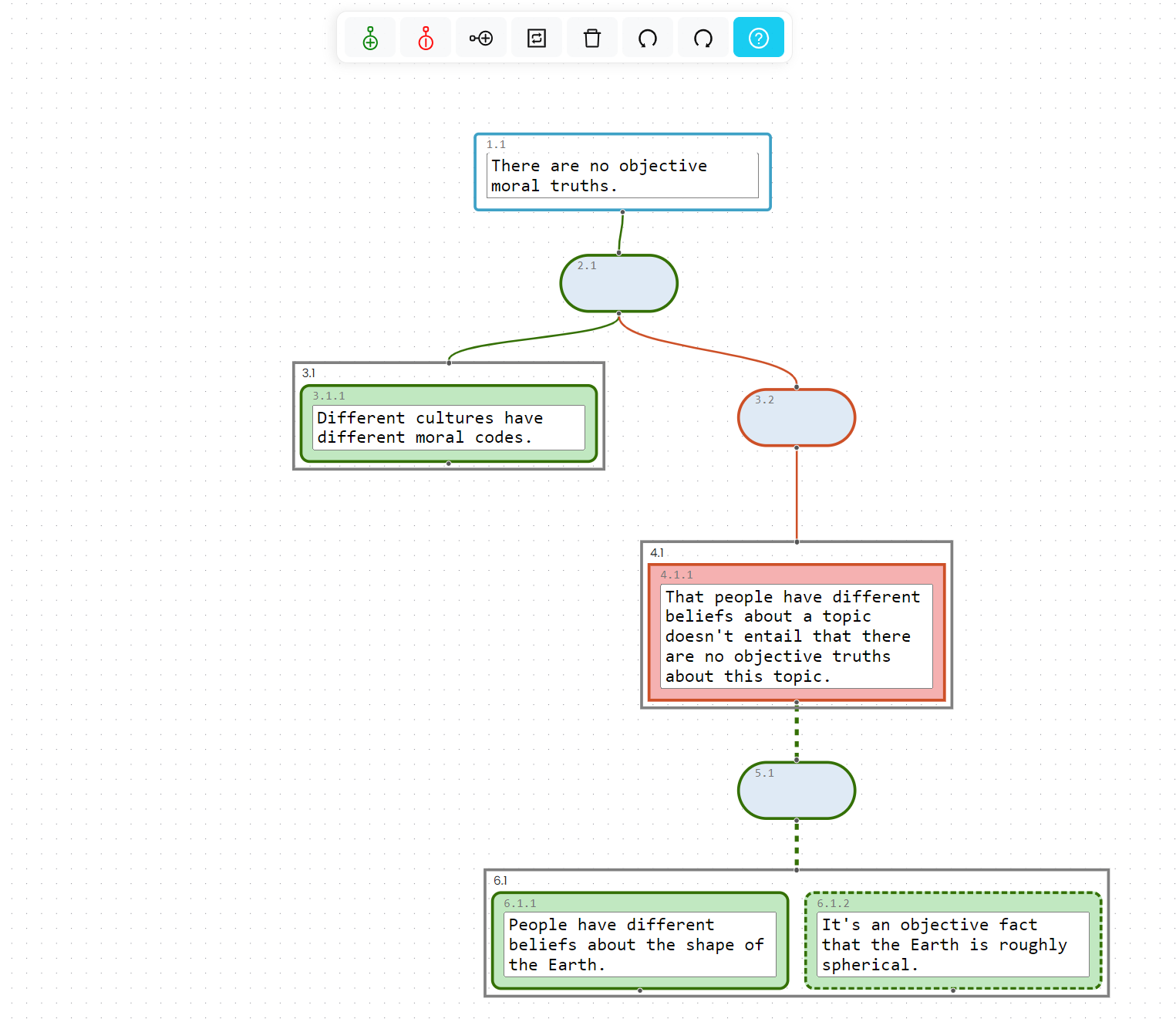

The inference box helps students learn about inference by providing a more intuitive representation of inferences and arguments for or against them. Conceptually, an inference is a connection between premises and a conclusion; an objection to an inference is an objection to a connection between premises and a conclusion. And in Argumentation.io, this is also what inferences and inference objections are spatially and diagrammatically. Here’s an example from Rachels’ “The Challenge of Cultural Relativism”:

Example of an inference objection.

Another advantage of the inference box is that it increases the user’s ability to edit their maps: they can drag and drop onto the inference box to turn an argument for or against an inference and they can drag and drop onto (the top of) a group box to turn a claim into a co-premise.

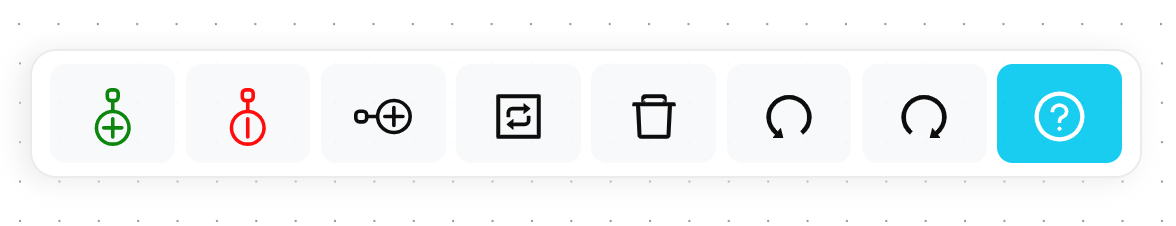

Finally, we’ve made Argumentation.io as simple, user-friendly, and self-explanatory as possible. We’ve kept the buttons on the main control panel to what’s essential for argument mapping and have given the buttons self-explanatory, color-coded icons:

As a busy teacher, I know how important it is to minimize my students’ technological difficulties. It keeps them happier and more focused on course content and it reduces the time I spend explaining technology and answering questions about it. I used Argumentation.io for my Spring 2023 courses and had my lowest rate of student technological problems since I started teaching argument mapping.

At present, the app has the core features that are essential to teaching argument mapping. We’ll keep adding new features over time.

In the coming weeks, we’ll release a six-chapter argument mapping textbook (co-written by myself and Zachary Poston), a teaching quickstart guide on all aspects of teaching argument mapping accessibly, and PowerPoint slides. We’ll bundle the textbook with the app. Together, these materials will help instructors set up and run a fully accessible argument mapping course.

Users can create maps in our app for free. We also offer subscriptions, which give users the options to save their maps in Argumentation.io, share them through links, or use the save as pdf or png functions. A subscription will also give the user access to the textbook, once we release it. An individual subscription costs $5 per month or $25 for six months. Universities and colleges can sign up for institutional subscriptions. These give everyone at the institution a subscription.

Promotion Code and Contact

Daily Nous readers can enjoy a free one-month subscription to Argumentation.io. To do so, create an account by clicking the Main Menu button (the button in the upper left-hand corner with the three horizontal lines), then clicking Login, then entering your email and password, then clicking ‘Create New Account.’ Once you’re logged in, open the main menu again, select Subscribe, select Monthly, and use the promotion code ARG1 at checkout. Instructors who use Argumentation.io for their courses can continue to subscribe for free.

If you’d like to learn more about Argumentation.io or how to incorporate argument mapping into your course, I’d be happy to talk with you about it, over email or in Zoom. You can reach me at [email protected].

Related posts about argument mapping

sick. how do I cite it?

https://applied-philosophy.org/home/f/argument-mapping—skills-for-the-ai-age

Amazing! Thanks for this, Steve!

Argument maps seem good for lower-level courses, or for honing in on narrow issues. But reasonably quickly into a philosophical discourse, someone usually makes a point about the meaning of a concept or a term, or the framing of a debate. Such a move is something that probably cannot be easily represented as a bifurcation in a tree, because it recontextualizes everything, changing the meaning or importance of the propositions higher in the hierarchy. Argument maps can blinker us to such argumentative moves that involve more than “making a point,” but also a “change in perspective.”

Hi Daniel,

Thanks, this is food for thought! Some initial reactions:

Am I doing this right?

Okay, I know this is just for fun, but the satirical argument that birds aren’t real because they’re government surveillance robots drives me crazy—it only follows that birds are (real) robots, not that they aren’t real! The kids need to read their Putnam!

If I am about to eat the plastic apple in the fruit bowl, you might tell me “stop, that’s not a real apple.” If a wizard waves their magic wand and turns all apples into plastic apples, we might say that there are no real apples left: they’ve all disappeared. And so if it turns out birds have been robots all along, I don’t think it’s strange to say that in fact there are not nor have there ever been any real birds. Maybe there do not need any real birds for birds to be real. But I’d say the charitable way to read “birds aren’t real” is as elliptical for “there are no real birds.” And I don’t think a robot bird is a real bird any more than a plastic apple is a real apple. Real apples are made of stuff you can eat. Only fake apples are made of plastic.

Perhaps you might reply that fake things are still real. They are real fake things. I wonder what the distinction is between a real fake thing and a fake fake thing. Maybe something cannot be a fake fake thing, because if it is a fake thing it is a thing, and all things are real. Or maybe a fake fake thing would just be a real thing: a real apple is a fake fake apple? So a fake apple would be a fake fake fake apple and a real apple would be a fake fake fake fake apple, etc.

(Of course, the actual answer is that “real” has multiple meanings in English. E.g. via Merriam-Webster, it can mean “having objective independent existence,” which is what you’re talking about, while another meaning is “not artificial, fraudulent, or illusory,” which is the sense being used in the discussion about the reality or lack thereof of birds.)

https://argumentation.io?share=8d240970-edac-4b0b-9570-df37b26fe78d

Hi Steven,

This is awesome! Great choice of topic.

I hope you don’t mind me replying in the mode of a teacher; I think this is a great opportunity to share some more about our book and how argument mapping can be taught with it, including giving students feedback. So some of what I’ll say might be obvious to you but it wouldn’t be to many students.

If you want to go straight to my version of the debate you mapped, to compare with your own, it’s here:

https://argumentation.io?share=ff5379e8-ab85-4f4d-afa2-03db40721734

(In the lower left-hand corner of the workspace, there’s a view panel with a button, below the zoom-out button, that zooms out to exactly the extent necessary to see the whole map.)

Your map makes great use of co-premises in many places. Also, most of the reasons support the claims they’re connected to and most objections oppose the ones they’re connected to.

There are two main areas for improvement: the use of inference boxes and objections to objections (specifically, box 6.1). (Again, for purposes of illustration, I’m writing this similarly to how I’d respond to a student.)

On inference boxes, remember that claims don’t go in them, names of inference rules do. See sections 1.9, 3.1, and some other sections in Chapter 3.

On objections to objections, see Sections 5.4 and 5.5.

Here are the passages I refer the student to (and also the table of contents), excerpted from our textbook With Good Reason: An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Argument Mapping:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HPLYr-2Wo2pFHeAWiZtTRwGaNvjuyrKR/view?usp=drive_link

Chapter 1 of the textbook also discusses “inference indicators” like ‘therefore,’ since,’ etc.

Each chapter has at least 30 exercises, so the student has plenty of opportunity to practice. That’s what argument mapping is all about.

Let me say a little more about the inference box, since when I designed this, I was worried it would confuse students.

In my spring 2023 courses, I talked to my students about inference boxes in class and had a section on inference indicators. I didn’t have the multiple discussions of the issue that I’ve put in With Good Reason or all the examples illustrating what goes in the boxes. Seeing that the box has ‘inference’ written in it, and that there are things called ‘inference indicators’ seemed to work for many students; they left the boxes blank or put inference indicators in them, which is basically correct. The rate of mistakes, like putting a claim in an inference box, was low. On the first quiz, 6/107 (5.6%) made this kind of mistake. On the second, 8/107 (7.5%) did. (And the mistake, in that case, didn’t impede understanding; I can explain why if there’s interest.) After that, it was less than 1%. This is about as low a mistake rate as one can expect for these introductory gen ed classes.

Ack, this is a reply to Jason. Sorry, no idea where I got ‘Steven’ from!

Can students work on a single map together (similarly to a shared google doc)?

Currently not similarly to a shared Google doc. To work on a map together on different devices, they’d have to share the link, open the map while logged into their account, save it to their account, make changes, and send back. So similarly to how people used to share Word docs through email, make edits, and send them back.

We plan to add real-time collaboration over the next year.

Let me 2nd this question/suggestion. The ability to have students collaborate on the maps is important to me. I currently use MindMup for argument mapping, but I’d be tempted to switch to your product if there were a way for students to work together. (For what it’s worth, MindMup gets a little glitchy when students are working simultaneously.)

Thanks for the feedback! We’ll raise the priority of this feature.

Does it only map directed hierarchical graphs, or can it represent non-hierarchical networks of mutually reinforcing claims?

I’m not familiar with non-hierarchical networks of mutually reinforcing claims. Could you give an example of one of those?

Just a note that like almost all accessibility requirements enshrined in law, section 508 of the ARA has an explicit “undue burden” exception, and designing a website to make argument diagrams machine readable is going to count as an undue burden every day of the week and twice on Sunday.

Hi Christopher,

I’m not a lawyer so I don’t want to offer what might be construed as legal advice; if readers are considering using a technology that’s not accessible, their institutions might be able to advise them on it.

However, I would urge caution in relying on the undue burdens clause to justify adopting non-accessible emerging technology. The reason is that one could avoid excluding students with disabilities by simply not adopting the technology, and eschewing an emerging technology isn’t generally considered an undue burden. This is from a 2010 letter by two DOJ Civil Rights attorneys to college and university presidents:

https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-20100629.html

You might be right that designing a screen-reader-compatible argument app wasn’t the easiest strategy for making argument mapping compliant with US federal accessibility law. Before I developed Argumentation.io, I considered developing a separate accommodation. However, I ran the idea by a blind person who knows a bit about accessibility and she convinced me to just make a new argument mapping app that blind people could use. It’s been a ton of work but I think it’s been worth it. Having one app (and reading materials) to use for a class, rather than a separate accommodation, will make things easier for instructors. And I imagine the students who would otherwise be excluded would, all else being equal, prefer it.

“Argument mapping is about twice as effective at improving student critical thinking as other methods.”

Sigh. Maybe someone with more time and energy can help me out here. I spent about 30 minutes looking at the four links and want to point out the following problems:

1. We don’t, as far as I can see, get any high-quality experimental or quasi-experimental designs that directly compare argument-mapping to another active intervention (such as a traditional critical thinking course) of the same intensity and duration.

2. The Cullen et al (2018) study is the source of the 0.71 effect size.* This is a single quasi-experimental study of Princeton freshmen. There is no randomization, and the authors don’t really show their work when they say the treatment group and the control are comparable. The control is not a critical thinking class. There are two measures, improvement on the LSAT and blind scoring of essays. These are the results: between group for the LSAT improvement measure (d = 0.71, 95% CI: [0.37, 1.04], p < 0.001) and for the essay: (d = 0.87, 95% CI: [0.26, 1.48], p = 0.005). Notice the wide confidence intervals.

So that 0.71 number needs to be taken with some caution, and we’re comparing apples to oranges in some cases—since we seem to be comparing between-group effect sizes in controlled studies to pre v. post effect sizes in uncontrolled designs cited elsewhere in the blog post. Moreover, there is a serious issue of external validity. Are Princeton freshmen representative of the population of college students liable to take critical thinking courses?

3. Moreover, let’s look at the actual intervention, as described in the Methods section of Cullen et al (2018):

“Between 2013 and 2017, 105 students participated in the seminar…. While students worked, three instructors circulated around the room, providing help or philosophical discussion when appropriate…. In addition to coaching during the sessions, students received detailed and individualized written feedback on their problem sets every week, which indicated errors in students’ understanding of the texts as manifest in their argument visualizations.”

This sounds pretty intensive, no? The authors don’t appear to consider the possibility that more instructor contact is moderating or mediating the relationship between argument-visualization and outcomes on the measures. I struggle to imagine those of us who teach critical thinking at large public universities adopting such an intensive teaching style. Again, there’s a real risk of comparing apples to oranges.

4. The other source suggesting a higher effect size for argument mapping is Van Gelder (2015). I am not sure where this was published. It does not look like the kind of piece that would have passed peer review at a journal specializing in empirical research. This piece purports to be a meta-analysis, but it does not contain a proper Methods section, nor does it explain how the literature review was conducted. It relies heavily on unpublished data. This is about all we get in the way of methods:

“For some years, we have been gathering relevant studies and pooling their results. At time of writing, we obtained results twenty-six pre- and post studies of AM-based instruction in a one-semester CT subject, from institutions in Australia, Europe, and the United States. Many of these are unpublished, but published studies include those found in Butchart (2009), Dwyer, Hogan, and Stewart (2011; 2012), Harrell (2011), Twardy (2004), and van Gelder, Bissett, and Cumming (2004).” (p. 189)

The author reports the overall aggregate effect size of the meta-analysis of 26 studies as 0.7. Again, though, author doesn’t show the work the way we would expect in a modern meta-analysis that passed peer review at a leading journal. In the next paragraph, the author goes on to acknowledge the issue I mentioned before, namely, that some interventions are more intensive than others. “Fifteen of the twenty-six studies were high-intensity, and the weighted average effect size for these studies is 0.85.” But what counts as high, low, and medium intensity? And what were the effect sizes for the other intensities? Etc. Moreover, how do we compare these intensities to a regular, run-of-the-mill critical thinking course many of us would teach?

Again, there’s a lot more that could be said about the problems with the author’s argument, but I hope the basic point is clear. The cited studies do not support the conclusion.

*Incidentally, in the behavioral sciences at least, the convention is that d > 0.8 is a large effect size, so this would, at least based on the convention from Cohen, be a medium effect size, not a large effect size, as the blog post claims.

Hi Alex,

Your point about teaching “intensity” as a potentially confounding variable in the Cullen article is a great one. From what I can tell, this is a topic deserving of further research. And sorry for getting the “large” effect size number wrong.

That being said, having looked over some research again with your point about intensity in mind, I remain convinced of the benefits of AM, for four reasons.

First, van Gelder’s claim about high-intensity AM courses, and what I take to be an implication about medium- or low-intensity AM courses, seems qualitatively right to me, even if he should have shown his work. His claim is supported by the two published articles on AM that figure in his meta-analysis and that aren’t on high-intensity courses, namely, van Gelder, Bissett, and Cumming (2004) and Butchart et al. (2009). (The van Gelder meta-analysis is from the Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education (2015) btw.)

van Gelder, Bissett, and Cumming (2004) got a 0.8 effect size in a course they describe as follows: “four graduated modules containing practice and homework exercises, 24 supplementary ‘lessons’ covering key concepts and procedures, and six tutorials on argument mapping. Each module contained a specification of the concepts and skills to be mastered in the module, a set of practice exercises, and a set of homework exercises.” That sounds like less work than the non-AM courses I used to teach.

Butchart et al. (2009) got a 0.45 effect size in their AM-based general CT course. That might sound barely better than an average non-AM course. But it’s actually a lot better: the Abrami meta-analysis (linked in the OP) found that a general critical thinking course only has a 0.3 SD effect on critical thinking. The 0.38 number is for mixed philosophy and critical thinking courses (mixed CT/subject courses are more effective than general CT). (Butchart et al. and van Gelder might not have been aware of this when they compared their outcomes to mixed courses or lumped the two together.)

Butchart et al.’s course sounds low-work: 12 weeks of standard lectures, a weekly, two-hour tutorial, and eight homework assignments that are a bunch of short-answer questions and one short essay. When they taught the same course in a different semester, without argument mapping, the effect size was 0.19.

Second, there’s also good reason to think that most people process certain kinds of information more effectively when it’s in the form of a diagram vs. text. And what we know about this difference, in my view, lends further plausibility to the hypothesis that argument mapping contributes to the impressive outcomes in the studies on it. Given what we know about “visual learning,” I’d be surprised if AM didn’t enhance CT courses. This article provides a nice overview of the research on this topic:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/thoughts-thinking/201811/improving-critical-thinking-through-argument-mapping

In particular, there’s Dwyer’s finding that, in experimental situations, test subjects remember more of an argument when presented with it as a map than as text; and research on dual-coding (visual-spatial/diagrammatic).

Third, we have good evidence that AM courses are highly effective at improving student critical thinking, essay writing, etc. As you point out, it’s possible that we could get the same results without AM if we teach more intensely. As a practical matter, if one is going to up one’s teaching intensity, one should do so in a way that’s been confirmed to work. I wouldn’t want to start grading way more without knowing whether it will do much good. This doesn’t address the specific argument of mine, about the empirical research on AM, that was the focus of your objection. But it’s worth keeping in mind.

Fourth, while I first started teaching argument mapping because I read the research on it, at this point, my views on it are influenced by my own experience teaching it. As I said in another comment, my intro students’ essays are now, on average, better than my upper-division students’. All the other AM teachers I’ve spoken with are similarly enamored with it. I realize such opinions of “informed judges” is unscientific. But I don’t think it counts for nothing, particularly when it coheres so well with more scientific research. And I also think we teachers often have to rely on our sense of what worked for us because we’ll rarely have high-quality RCTs to guide our teaching decisions. Teaching used to be a chore for me; now it feels like a way to make the world a better place.

I have never used argument mapping, but have meant to try it out. One reason to do so now is that it might help with the ChatGPT problem. At present, it does not seem that ChatGPT can argument map. So one can assign argument mapping without worry. In addition, one might be able to use it to ensure that students do substantial work on their essays. If a student is required to write an essay built on an argument map, they might be able to get the essay from ChatGPT, but will still have to reverse engineer the argument map, which is at least a significant amount of philosophical work.

Can ChatGPT identify and reconstruct arguments from a passage in any of the various so-called “standard form” styles? (For example, as in: P1). . . . (s[entence] #3) / P2) . . . . (s#4) / ________ / C1/P3) . . . . (implied by s#3) [Putatively deductively valid inference from P1, P2] / P4) . . . . (s#2) / ________ / C2) Probably, . . . . (s#1) [Putatively inductively forceful inference from P3, P4]? If ChatGPT can’t do that, then many of us already use non-mapping approaches that ChatGPT hasn’t mastered. But if ChatGPT is already good at creating standard form argument reconstructions with nicely labeled parts, then yeah, I might consider trying a mapping approach.

I gave ChatGPT the following prompt:

Here’s its reply:

If you’ve waited until the last minute to start designing your course, please consider our textbook, With Good Reason. You can download it from Argumentation.io with a subscription. Use subscription code ARG1 for a free one-month subscription.

Here’s a description of the textbook:

https://sites.google.com/view/jonathanreidsurovell/with-good-reason

Students will soon be able to buy a book/app subscription bundle through Perusall. If there’s interest, we should be able to arrange the same thing with your university bookstore. And we offer institutional subscriptions.

I’m also happy to share assignments, rubrics, and lecture slides for a course based on Argumentation.io and With Good Reason.

Glad to see another free, no-account-needed website for argument mapping.

But I’m curious why one would use Argumentation.io over MindMup.com, which seems to have more features, less visual clutter, and more integration with cloud services like Google’s and Microsoft’s. If you’ve mapped that part of the pitch, I’d be very interested to get the details.

Thanks for this important work!

Thanks also to Alex for enhancing the analysis of the alleged benefits of argument mapping!

Hi Nick,

Thanks for the feedback! We’ll take another look at integrating with a cloud service.

Argumentation.io’s main advantages over MindMup are accessibility, user-friendliness, and the inference box. What I say in the OP about the novelty of our app in these respects applies to MindMup, I just didn’t mention them by name.

On clutter and number of features: based on user interviews, we decided to go with only the features that are absolutely essential to argument mapping, so as to keep the user interface as clean and uncluttered as possible. If Argumentation doesn’t have a feature you like, including something to do with cloud integration, I’d love to hear your feedback. We expect to add real-time collaboration within the next few weeks. We decided to add that based on feedback we got in comments in this thread!

When you say Argumentation.io is more cluttered, are you talking about the inference boxes? I’m a fan of these, for the reasons discussed in the OP. Also, I’ve recently learned of benefits of the inference box that I didn’t foresee when I designed them:

1. My students have really surprised me with their understanding of inference rules like IBE this semester. I don’t think I could teach this without the inference boxes.

2. The treatment of inference afforded by inference boxes has allowed me to teach other argument mapping topics more effectively. For example, you can use inferences in explanations of the difference between co-premises and independent reasons. Traditional material about evaluating analogical arguments (sample size, relevance of analogy, etc.) can be mapped as objections to an inference box with ‘analogical argument’ in it. The inference box opens up a lot of possibilities.

It’s hard to teach about inferences with MindMup because it uses two distinct diagrammatic objects for a single inference. When you give an inference a name (‘A’ or ‘analogical argument’) it goes on the line connecting premises to contention. When you object to an inference, your objection goes under the bracket encompassing the co-premises (the idea being that it’s an objection to an unstated co-premise). So you can’t simply tell students, of any one thing in the diagram, “this is the inference,” without risking confusion.

What I think this shows is that the inference boxes aren’t really clutter; they’re making visible something that’s “really there.”

One other thing I didn’t mention in the OP: MindMup is really a pair of sites–an argument mapping site and a mind mapping site. The two sites look very similar. When I taught with MindMup, many students would get to MindMup by googling it and this would lead them to the mind mapping site, rather than the argument mapping site. They were unable to make argument maps there, and generally didn’t realize that what they were making wasn’t an argument map.