To Be a Department of Philosophy (guest post)

“There are many reasons to expand the story we tell about philosophy. But a main reason is just that the best, most interesting, and even the correct answers to philosophical questions that interest us might be found anywhere.”

The following is a guest post* by Alexander Guerrero, Professor of Philosophy at Rutgers University. It is the second in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

[Gaba Meschac – Globallon (detail)]

To Be a Department of Philosophy

by Alexander Guerrero

The profession of philosophy and the education of philosophy students—at both the undergraduate and graduate level—must change.

It has now been almost exactly six years since Jay Garfield and Bryan Van Norden published their “If Philosophy Won’t Diversify, Let’s Call It What It Really Is” in the New York Times, and it has been five years since Van Norden published his follow-up book, Taking Back Philosophy: A Multicultural Manifesto. They and many others have been pointing out, for years, that the vast majority of philosophy departments in the United States (and most other parts of the Anglophone world) offer courses only from one strand of the world’s philosophical traditions, the Anglo-European strand. (And even within that strand, it is narrow, giving prominence to Ancient Greece, France, Germany, the UK, and the US.)

As those of us who went through such programs know, this story begins in Ancient Greece with fragments of Thales and Parmenides and a few others, and considerably more from Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle; skips forward to Medieval Europe and Anselm and Aquinas (or skips this period entirely); continues through a few prominent ‘early modern’ or ‘modern’ Anglo/European men (Descartes, Hobbes, Locke, Hume, Kant, maybe also some Leibniz, Spinoza, and Rousseau); picks up a few others in the 19th Century (Bentham, Hegel, Nietzsche, Marx, Mill); and arrives with an early 20th century philosophy origin story that goes through Frege, Russell, Carnap, Wittgenstein and into central figures like Quine, Kripke, Lewis, Rawls; and then a topically-driven focus on many distinct philosophers in the last quarter of the 20th Century and early 21st Century on the analytic side (substitute Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Derrida, Merleau-Ponty, Deleuze, Foucault, etc., on the continental side). The dominant version of the story includes no chapters on African, Chinese, Indian, Latin American, or Indigenous or Native American voices or views; nothing (or almost nothing) from the long grand traditions intertwined with Buddhism, Islam, or Judaism; nothing from other non-Anglo-Europeans.

This story of philosophy has been overwhelmingly male, overwhelmingly white, and, as Garfield and Van Norden are at pains to point out, overwhelmingly Anglo-European, dominated by Europe, the UK, and, joining later, the United States. Why is this the story that has been told, over and over again, to undergraduates moving through philosophy programs? Why is this the story that we continue to tell through our major requirements and PhD distribution requirements?

There are two broad families of answers. The first aims at justification and vindication: here are the substantive, justifying reasons why this is what we teach and require and put at the center of ‘Philosophy’ in our educational institutions. The second aims at debunking these justifications (arguing that there is no justification for doing things this way) and supplementing that with diagnosis and historicization: here are the empirical explanations for why this what we do; notice that there are no justifying reasons in that story, nor no new justifying reasons to embrace now.

The first kind of answer makes a substantive claim about philosophy. It claims that, in sticking to the story above, we teach and require everything that is most centrally well-described as philosophy. We leave out, or put to the margins, work that is just religion, or anthropology, or literature, or cultural studies, or “thought” that doesn’t constitute philosophy.

I’m not sure anyone still really believes this. At any rate, they shouldn’t.

This kind of answer requires (a) that there is some kind of meta-philosophical view for sorting things as ‘philosophy’ or not, (b) that it is an attractive, non-question-begging meta-philosophical view, (c) that those telling this standard story agree on this view and use it to sort work into the ‘philosophy’ basket or not, (d) that this view compels us to include what we teach and require but exclude what we don’t currently cover, and (e) that this sorting just happens to include only Anglo-European work and almost nothing from non-Anglo-Europeans prior to 1950 or 1960 or something like that (at which point Jaegwon Kim and a few others get to become the very first non-Anglo-Europeans ever to do philosophy!). (Or perhaps there isn’t just one meta-philosophical view that all agree on, but, by amazing coincidence, the various meta-philosophical views are all such that they get extensionally equivalent results regarding (d) and (e)?) That is already quite a lot to swallow. I know that, at least in the places I’ve been, I would not expect any kind of broad meta-philosophical agreement, nor has there been any recent sorting or meta-philosophical discussion. What would the meta-philosophical view be? Something about arguments? Arguments about certain topics? Counterexamples—from inside and outside our standard story—abound. Garfield and Van Norden offer many of these.

But, even more decisively, we can tell that this isn’t what is really going on, because of the second difficulty with this answer: those who endorse it have either no or only glancing acquaintance with work from these other traditions, so the actual explanation for inclusion or exclusion can’t be some faithful, careful application of an attractive meta-philosophical principle. Nor can we defer to our wise forefathers (and they were certainly almost all men) who first crafted this story by using some (now forgotten) beautiful meta-philosophical sorting principle. We might not know that much about them, but one of the things we do know is that they, too, knew very little about any work that isn’t part of the standard story.

I expect that almost all of us teach and study in departments in which we just inherited the basic structure of coverage and the (at best) implicit understanding of philosophy revealed by that structure. These are the courses on the books, these are the professors we have to teach them, this is what I learned about in my philosophy education, these are the readers and textbooks we use, this is what we know about already, so, this is philosophy.

Obviously, that’s not any kind of argument toward substantive justification. We might try to come up with some attempts at post hoc rationalizations, but, once we acknowledge we don’t know anything at all about what is in the shadows, why should we continue to maintain that the pedagogical light is shining in just the right place?

The main answer to this is a human one: it’s natural to feel defensive and protective of what you have come to know and love. The vital point—at least by my lights—is that the problem with the standard story isn’t what it includes: what we all have come to know and love is, in many deep ways, important and beautiful. It makes sense that we want it to be taught and studied forever. The problem with the standard story is entirely about what it excludes. Figuring out how to move forward, figuring out how to begin telling a different, broader story, requires looking backward to better understand these patterns of exclusion. The second kind of answer to the ‘why this story’ question—the debunking and historicizing answer—helps us in that regard.

The second answer to our initial question of why this is the story of philosophy that we offer focuses on historical factors, explaining why we are in this situation without purporting to justify it. The long version of this story would need to be told by someone with more knowledge and historical and sociological expertise than I have. Randall Collins, in his unbelievably comprehensive masterpiece, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, tells some relevant parts of this story, focusing on the shift of philosophy into universities, particular networks of philosophers and intellectuals and the stories they tell about their own origins, and the gradual accumulation and ossification of a story as generations of students encounter it and learn about the key figures within that story (and, just as importantly, do not learn about other things).

Most of us who went into philosophy didn’t know all that much about what it was; we learned via example and ostension: this, these texts, the writings and ideas of these people, is philosophy. We have been told various things to justify this particular set of people, these starting points and texts. But often what we were told is just something said on the first day or two of class, not rigorously questioned or challenged even by those telling us the story. We are all, after all, mostly philosophers, interested in philosophy, not intellectual historians, interested in intellectual history. Once we have some interesting philosophy in front of us, we might not be inclined to ask all that many questions about what we haven’t been shown and why.

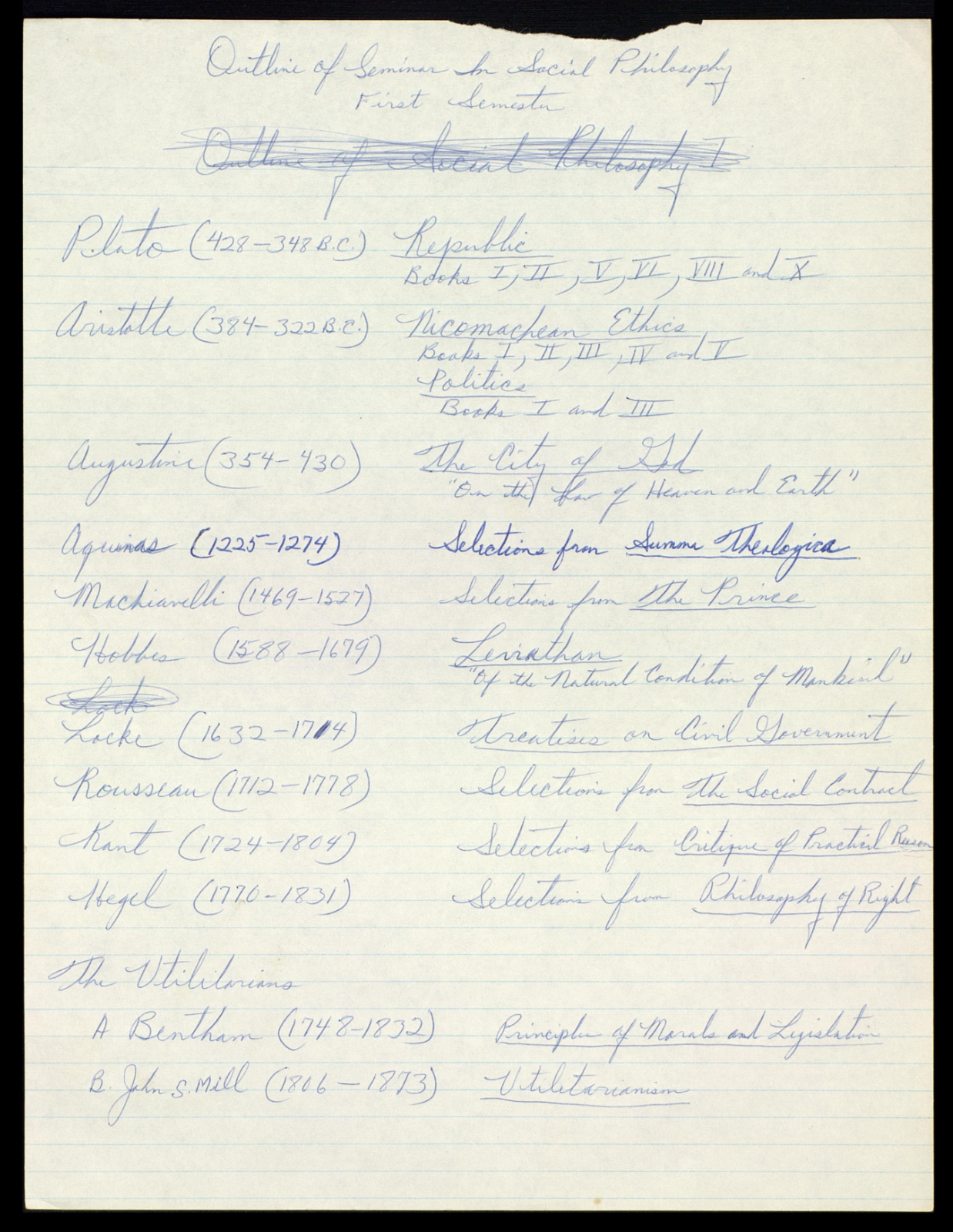

So, for much of the recent history of philosophical education in the Anglo-European world, what was pointed 75 years ago is still what is in the story today. Martin Luther King Jr.’s syllabus for an introductory social and political philosophy class he taught at Morehouse College 60 years ago could be identical to one that might be taught today.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s outline for his social philosophy seminar at Morehouse College

For some significant part of that time, many of those doing the pointing have plausibly had biases against work by women and work by non-White people. Racism and sexism are part of the story of exclusion.

But another key part of the story is just a story of cycles of ignorance: your teachers don’t know about X, so they don’t teach you about X, so you don’t know about X, so when you teach you don’t teach about X, so your students don’t know about X… It might be that what falls under ‘X’ is a result of racism and sexism. It might also just be a matter of what is easily accessible at a particular time and place. We live at a time of unprecedented access to texts, ideas, and traditions from throughout history and from around the world, in addition to sophisticated scholarly commentary on and distillation of all those texts, ideas, and traditions.

Those parts of the explanation suggest good news and concrete steps for the project of beginning to tell a different story. I will suggest six such steps, concerning both undergraduate and graduate philosophical education. These might not all be equally easy to implement, depending on one’s particular local situation. But I hope that many of them can be taken up by those involved with philosophical education in almost any educational setting.

(1) Continue Your Philosophical Education

First suggestion: if you regularly teach philosophy, see it as a personal project to develop competence with material in your areas of specialization and/or competence from a philosophical tradition outside of the Anglo-European tradition that could be brought into your regular teaching (and perhaps also your advising and research).

Very few people who graduated with an undergraduate degree and a PhD in Philosophy from schools in North America, Australia, or the UK will have had any courses in any of Africana, Buddhist, Chinese, Indigenous or Native American, Indian, Islamic, Jewish, Latin American, or any other non-Anglo-European philosophical work. This is the central mechanism of the vicious cycle of ignorance that keeps us where we are. The only way to get out of the cycle is for many of us who were exposed only to the standard story to do some work. We can’t wait for someone else to do it. We aren’t teaching anybody else to do it. As Garfield and Van Norden wrote in 2016:

The vast majority of philosophy departments in the United States offer courses only on philosophy derived from Europe and the English-speaking world. For example, of the 118 doctoral programs in philosophy in the United States and Canada, only 10 percent have a specialist in Chinese philosophy as part of their regular faculty. Most philosophy departments also offer no courses on Africana, Indian, Islamic, Jewish, Latin American, Native American or other non-European traditions. Indeed, of the top 50 philosophy doctoral programs in the English-speaking world, only 15 percent have any regular faculty members who teach any non-Western philosophy.

Very little has changed in this regard in the past six years. There are excellent people working in these areas, but there are simply not yet enough people who are experts in these areas, and the vast majority of PhD programs in Philosophy are not producing people who work or teach in these areas.

Fortunately, one thing that is changing significantly are the resources available to people for their own continuing philosophical education with respect to work from outside the standard story.

There is a new program, the Northeast Workshop to Learn About Multicultural Philosophy (‘NEWLAMP’), which has this as its central purpose. Twenty philosophy instructors from across the country will meet in July to expand their knowledge of African and African social and political philosophy. Future iterations will cover different traditions and topics. More such programs should be created.

But there are also many things one can use on one’s own, or in a small reading group. Last Spring, I ran a reading group on African, Latin American, and Native American philosophy over Zoom. This was very fun and relatively easy to do. All the readings and plan are available here, and many other similar groups could be organized, covering all manner of topics.

Perhaps the single-most remarkable resource, The History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps project, now has extensive coverage of Islamic Philosophy, Indian Philosophy, and African Philosophy, thanks to the truly amazing work of Peter Adamson, Jonardon Ganeri, and Chike Jeffers, among others. The future plan includes coverage of ancient China with the help of Karyn Lai. It is helpfully organized chronologically but also indexed thematically, so that one could learn just about aesthetics or ethics or mereology.

Familiar resources, like the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and Philosophy Compass, are significantly expanding their coverage of philosophical work from outside the Anglo-European tradition. For example, Guillermo Hurtado and Robert Eli Sanchez have created a remarkable overview entry for the SEP on Philosophy in Mexico, there is a fantastic entry on metaphilosophical questions concerning ‘Latin American Philosophy’ authored by Susana Nuccetelli, and Stephanie Rivera Berruz has written a brilliant entry on Latin American Feminism. Philosophy Compass has new Section Areas on African and African Philosophy, Indian Philosophy, Latinx and Latin American Philosophy, and Native American and Indigenous Philosophy, to accompany the longstanding Section on Chinese Philosophy. Keep an eye out for articles that will helpful both for professors looking to get their bearings and for assigning to students. Also, check out The Philosophical Forum, as Alexus McLeod (a world expert on several different philosophical traditions from outside the standard story) has been brought on as the new Editor of that journal, and he aims to make it a leading forum for work from all philosophical traditions.

There are several great blogs and other online communities to help one get a sense of the people working on these topics now, and to become familiar with some of the topics and issues. Warp, Weft, and Way, focusing on Chinese and Comparative Philosophy, is one of the most active and oldest blogs. 20th Century Mexican Philosophy provides discussion and links to many valuable resources. The Blog of the APA has been running a series of posts on teaching material from outside the traditional canon, such as this wonderfully helpful entry by Liam Kofi Bright and Peter Adamson, So You Want to Teach Some Africana Philosophy?

The Center for New Narratives in Philosophy, directed by Christia Mercer, is creating events and other resources aimed at bringing work from outside of the standard story into view. This includes a book series, the Oxford New Histories of Philosophy (co-edited with Melvin Rogers), which brings both primary texts and secondary materials helping to make accessible and “available, often for the first time, ideas and works by women, people of color, and movements in philosophy’s past that were groundbreaking in their day but left out of traditional accounts.”

Bryan Van Norden has put together a remarkable bibliography of readings on Africana, Chinese, Christian, Indian, Indigenous, Islamic, Jewish, and Latin American philosophy, including many helpful suggestions under the heading ‘Where Should I Start?’ for each of these areas.

As I hope is clear, although it might have been hard to know where to begin 10 or 15 years ago when thinking about trying to learn more, it is considerably easier now. Please mention other resources in the comments!

(2) Make Connections at Your Institution

There are almost certainly philosophers and people teaching and studying philosophy outside of your home institution’s department. They are quite likely to be teaching and studying philosophical work from outside the standard story. They might be in Departments of Religion, East Asian Studies, History, American Studies, Africana Studies, Comparative Literature, and so on. Learn about who they are. Reach out to them. Build connections between them and the Philosophy department. Co-teach with them. Co-organize conferences with them. Encourage your Philosophy students to take their classes. Cross-list their classes with Philosophy. Give them a presence on your departmental webpage. Perhaps, if it makes sense, pursue giving them more institutional power within Philosophy (through joint-appointments and so forth).

(3) Create Courses to Expand Your Department’s Story About Philosophy

Once you have identified what is already offered at your institution, think about what isn’t being covered, even if those courses are brought also into philosophy, and learn enough to create introductory courses on that topic or to bring that material into existing courses. This is actually one of the best ways to take up the first suggestion, as nothing helps one learn a topic more than teaching it.

At many institutions, it is not very difficult to get a new course on the books. In my experience, it was very easy to get institutional approval for a new course on African, Latin American, and Native American Philosophy. (You can read about my experience in that regard.) Most departments at most institutions are already way ahead of Philosophy in expanding the story they present to students, and administrators are excited when this happens. My philosophy colleagues have always been nothing but supportive in this regard. I expect yours will be, too.

There is now a remarkable collection of syllabi collected by the American Philosophical Association on topics in all of these areas. These are excellent for making it easy on new instructors, so that you don’t have to start from scratch.

Even if you don’t create a whole new course, work on adding material from outside the standard story into your classes in Ethics, Epistemology, Metaphysics, Mind, Political Philosophy, and so on. Many of the above resources will help in that regard, too, and this is, in some ways, an even more direct way to expand the standard story and to make evident the way in which philosophy really is a subject that has been done by people of all kinds and everywhere.

(4) Change the Official Story Your Department Tells – Undergraduate Level

Once you have identified courses being offered at your institution that expand the standard story, or once you and your colleagues have increased your knowledge and created such courses, start requiring your undergraduate and graduate students to take these courses.

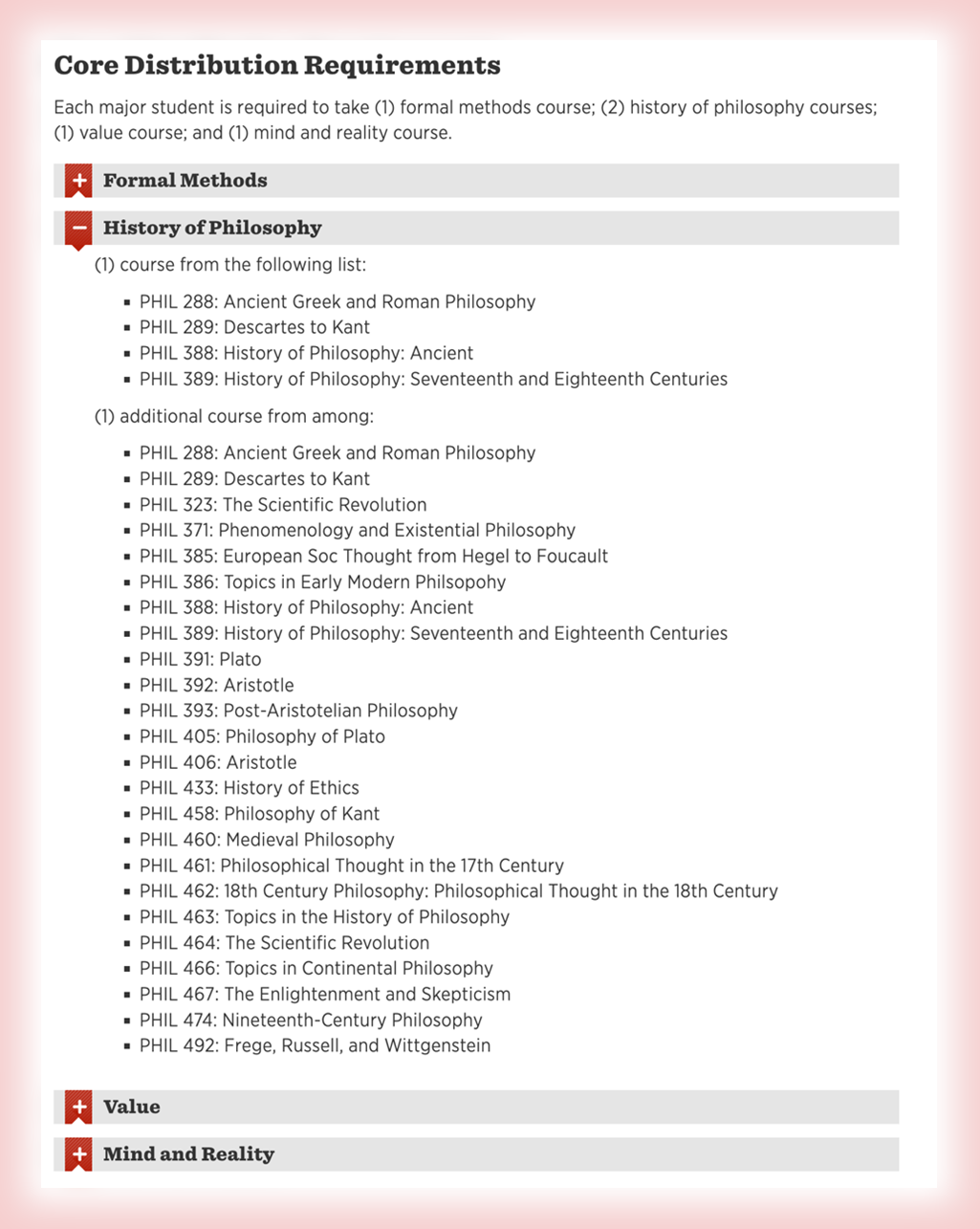

At many institutions, the Philosophy major is structured so that philosophy majors have to take something like 11 or 12 total philosophy courses, with 1 course in Logic, 1 course in Ancient or Medieval Philosophy, 1 course in Modern Philosophy, 2 courses in Metaphysics, Epistemology, or Language, 1 course in Moral or Political Philosophy, and then 5 or 6 electives, spread out over courses at varying levels. This is the basic pattern at Rutgers, Penn, and NYU (the three philosophy departments that I have spent the most time in, but also three pretty different institutions), but it is also similar to some places that have specialists on the Philosophy faculty who work on topics outside the standard story, like Michigan. Often, there is a list of courses on historical topics that specifies which courses can count as fulfilling the requirement, and that list almost always leaves off courses that aren’t part of the standard story. At Michigan, for example, these are the courses that count for history:

At Rutgers, we somewhat regularly offer courses on African, Latin American, and Native American Philosophy, Hindu Philosophy, Buddhist Philosophy, Islamic Philosophy, Jewish Philosophy, and Chinese Philosophy, but these are not listed as courses that fulfill any of the philosophy major requirements.

Given that many are very attached to everything currently required as part of the standard story, an easy initial recommendation would be to add in an additional requirement for a course from one of these other traditions, once those courses are being offered regularly enough at one’s institution. Prior to that, I would suggest pushing so that they can count as alternative ways of fulfilling existing requirements, but I know that is likely to engender more controversy.

Having these courses either be required for the major or at least count for a major requirement is essential for changing the story. It also is essential for creating a new generation of philosophers with more competence than the ones before it with respect to work outside of the Anglo-European tradition. In my experience, these classes are also very popular and bring in many students who might not otherwise have been considering Philosophy as a field of study.

Please, share in the comments if you teach at an institution that has made changes in this direction!

(5) Change the Official Story Your Department Tells – Graduate Level

Obviously, there are tens of thousands more students learning philosophy at an undergraduate level than at a graduate level. But if departments of philosophy are ever going to change the story they tell at any kind of scale, it will need to be through making it easier to get a PhD in Philosophy while also working on philosophy from outside the standard story. This is also vital for creating philosophers who can work on these philosophical ideas and traditions as researchers, bring them into conversation with other philosophical work, and do so at a high level of sophistication and competence, learning the relevant languages, and so on.

An initial, somewhat modest set of steps is to encourage MA and PhD students to take up the first suggestion, learning about philosophical work from outside the standard story in an area that is an AOS or an AOC. They might do this via directed reading groups, teaching their own courses on these topics or TA-ing for courses that faculty teach, or other mechanisms from your program that help to provide both time and support for those doing this. This has obvious non-instrumental benefits, but there also now is a significant demand for new faculty with competence or expertise in these areas. As Marcus Arvan documents, the number of jobs in ‘Non-Western’ Philosophy was roughly half what it was for all of Mind, Language, Metaphysics, Epistemology, and Logic combined. Developing an AOS or even an AOC in these areas might really help students on the job market.

Of course, to do work in these areas in a serious way will be hard (even if not impossible) to do without more direct expert advising. And there are very few people teaching in Philosophy PhD programs who are experts in these areas. This is not a trivial problem, given the current composition of faculty at most PhD programs in North America, the UK, Australia, etc. Most such faculties include no one who can advise a dissertation on these topics or traditions. (To find those that can, or to find potential experts to consult, you might look to The Pluralist Guide for some of these areas, or to the discussion on Warp, Weft, and Way concerning graduate programs in Chinese Philosophy.) And although departments could hire away experts from some of the other institutions out there, this won’t address the overall numbers problem. (It still might be an important signal to the profession if more ‘fancy’ PhD programs were to do this.)

To address this concern, an obvious initial step is to look within one’s institution, as suggested above, to see if there is expertise on these philosophical topics outside of the philosophy department.

An additional obvious next step is to actually hire people who are experts and specialists on philosophy from outside the standard story. That’s not always possible, of course, but when one sits around in a department meeting thinking about what holes there are in the current program coverage, one should start to take these holes more seriously.

A somewhat less obvious step, but one that I think deserves more consideration and discussion, is to hire (at adequate compensation) experts from other institutions to teach mini-courses, give lectures, and perhaps serve as outside advisors for students at one’s institution.

The overall suggestion here is to do what one can to support PhD and MA students in becoming experts and competent teachers with respect to philosophical work outside the standard story.

(6) Hire People Who Know More of the Story

As some of the foregoing suggestions indicate, there are things that people should do even if they can’t bring experts in these areas into faculty roles in their department. But that is obviously an excellent thing to do if it is a possibility. Just as it is impossible for most graduate programs to be excellent in their coverage of every single area of even the standard story, it won’t be possible for graduate programs to cover all of these areas and philosophers. But departments can develop specializations and strengths in some of them, and if some of those are outside the standard story, that will do quite a lot to change the perception of the department and the field.

* * * * *

Many of these suggestions ask for some effort and even sacrifice on the part of current professors and graduate students in philosophy. It’s worth talking about the reasons to see this both as beneficial and morally imperative. There are several reasons, and they do not compete, although they may differ in the degree and nature of force they provide.

The first is already obvious, I would expect: if one of the main reasons we tell the story we do through our philosophy curriculum and requirements is simply historical racism, we should do something about that. Continuing to do nothing, to just run out the exact same philosophy curriculum and to produce students with the exact same limited understanding of philosophy, is to both be complicit in that racism and to perpetuate it. Perhaps one thinks that racism plays very little role in the initial crafting of the story; it was, instead, just that people taught what they knew about and what was available to them. That just makes us doing nothing all the worse. It is then our racism—or culpable negligence, or something close to that—that is keeping the story alive. Because work from all these traditions is, at this point, relatively easily available to us.

This is the kind of scolding reason. It’s also a problem: none of us like to be told that we have to do anything. That’s why we got into philosophy! It’s also a disaster! Because—in my experience—every person I’ve seen encounter ideas and arguments and thought experiments from these other traditions finds something there to be excited about. There’s something for everyone, whether one works in ethics, epistemology, metaphysics, mind, language, political, social, logic, or anything else.

And it’s not surprising that it is exciting. It provides a new dimension of interest and even a kind of validation to see that people in considerably different sociohistorical circumstances might have also been thinking about some of the same things that keep you up at night. Comparative philosophy, whether across history or cultural difference or both, is tricky, and it is easy to be too quick to see commonality even when the reality might be more complicated. But it is undeniable that there are many common questions and concerns, and many interestingly different and interestingly similar ideas and arguments.

And for those of us interested in philosophical ideas, there is a more basic kind of excitement: meeting something new and beautiful and possibly bewildering that helps you understand something you are fascinated by and care about.

There are familiar arguments that racism is inefficient: by only considering people from one racial group for hiring, for example, one narrows one’s search in an arbitrary way, missing out on brilliance and ability for no good reason. Here, too, in the quest for philosophical truth, racism is inefficient.

If you think there are better and worse answers to philosophical questions, or even correct and incorrect answers to them, some worries emerge with the dominance of the standard story. The “streetlight effect” is the name of a kind of observational or investigational bias that occurs when people are searching for something but look only where it is easiest, rather than all the places where the thing might be (based on a story of a drunk person looking under the streetlight for his keys, even when he is pretty sure he left them in the enshadowed park across the street).

There are many reasons to expand the story we tell about philosophy. But a main reason is just that the best, most interesting, and even the correct answers to philosophical questions that interest us might be found anywhere. If we think there are genuine answers here, we should be concerned about parochialism. And we should be concerned about the streetlight effect.

To be a department of philosophy, we must change the story we are telling.

Related:

- When Someone Suggests Expanding the Canon

- Philosophical Diversity in U.S. Philosophy Departments

- End Philosophical Protectionism,

- Two Models for Expanding The Canon

- Bad Arguments Against Teaching Chinese Philosophy

- Why Don’t We Study African Philosophy?

Other resources:

I should add, too: although the college is ending, along with its philosophy program and first-year two-semester Philosophy and Political Thought course, Yale-NUS College, where I teach, has striven to do many of the things Alex describes in this excellent, thorough post.

If anyone is interested in hearing how philosophers with little to no previous experience in Indian philosophy managed to teach a global philosophy course spanning multiple philosophical traditions and thousands of years, and how they found it fruitful for their own research, my podcast has short, fifteen-minute interviews with current and former philosophy faculty (Season Three: https://sutrasandstuff.wordpress.com/seasons-and-topics/)

Tomorrow (1 June 2022 Eastern Time), I’m airing an interview with Robin Zheng, now at University of Glasgow. She talks about connections between contemporary feminist philosophy and premodern Indian philosophy.

My hope is that this series will encourage others to experiment in their own courses.

On a personal note, I’m happy to email with anyone interested in teaching Indian philosophy or in expanding their research interests in that directions.

Finally, I might add to this remark:

Yes, and also: studying other philosophical traditions can expand our understanding of what counts as philosophical questions. Mark Siderits has a nice metaphor for expanding the philosophical canon in his latest book, How Things Are, of global philosophy as being like viewing through a stereoscope. The two images we experience are slightly different, resulting in a kind of “queasiness” until one learns to adjust and see through the two lenses together.

In the spirit of this metaphor, I’d suggest that bringing together the different methods and organization of the discipline of philosophy (and its analogs globally) can result in some unease, since there may not be perfect alignment even in how we’re investigating the world or what we’re focusing on. But it may lead to more depth in our experience, as Mark and many others have suggested.

Some might find this helpful with regard to comparative philosophy: https://www.academia.edu/46923618/Thinking_about_Comparative_Philosophy_a_bibliographic_introduction

I’m genuinely curious, as someone who supports broadening and globalizing the *historical* canon in philosophy, how widely this argument goes. For example, much contemporary philosophy is, at least in terms of participants, “global” (though written in English). As someone who neither teaches nor particularly likes the history of philosophy, I’ve wondered how best to incorporate these kinds of arguments into my own teaching which typically doesn’t touch things written more than about 40 years ago.

Are these arguments targetted, as they seem to be, at those who primarily teach “History” of philosophy? If so then it makes a lot of good sense. It also makes sense, to a degree, to think about the normative traditions that have arisen outside of the standard Western story (i.e., outside of utilitarianism, deontology, contract theory, virtue ethics).

However, suppose we’re largely teaching courses that have little direct contact with the “deep” history of philosophy. I can understand how someone might see, for example, 20th and 21st century philosophy of mind (or psychology for that matter) to be deeply rooted in the Western tradition though even global research on the mind, the brain, etc., have converged on something like naturalism (I know I know…everyone disagrees about everything but here I mean this in the thinnest sense of naturalism as a commitment to a very weak empirical thesis). Similarly, suppose we teach courses in artificial intelligence or some other technology-related area (genetic engineering, etc.). To what degree are we under an obligation here not just to make sure that we’re reading literature being written today but people around the world but research that is steeped in (broadly) non-scientific traditions?

I don’t think I owe students, for example, a deep dive into psychoanalytic theory in order to talk about mental states nor, for similar reasons, do I think that quasi-religious theories (Western and Non-Western) should have a deep place in that sort of class. Am I wrong about these sorts of thoughts? I ask this as a genuine question and from the position of someone eager to learn more so please don’t take this question as sarcasm.

Yes, my own view is that whether there is relevant philosophy from non-Anglo-European traditions out there on some topic or not will depend on the topic (no different than, say, whether there is some part of Kant or German Idealism that bears on the topic).

For example, if you work on philosophy of quantum mechanics, there might be work written by people from all over the world that is relevant, but it won’t necessarily be drawing on a distinct philosophical tradition (or that tradition is something like ‘contemporary global analytic philosophy of science’). It would obviously be bad to only read work written by Anglo-European men on the topic, but that seems to me to be a different matter. I teach plenty of courses where we don’t read anything written more than 10 or 15 years ago. It is totally fine by my lights for there to be lots of classes like that.

But I do think that for many other philosophical topics, there is much work that is relevant from other philosophical traditions or perspectives, in some cases including *contemporary* philosophical perspectives, held by contemporary living philosophers, from outside the Anglo-European world. So, to speak to your example re: artificial intelligence, if one is teaching about ethical issues relating to data privacy and design of AI/ML systems, one might find it useful to engage with the work of Sabelo Mhlambi, who draws on the concept of ubuntu in engaging those issues. https://sabelo.mhlambi.com/ubuntu/

As discussed in the other thread, there is interesting, provocative work, drawing on modern interpretations of Confucianism, being done in China by Tongdong Bai and others concerning non-democratic, non-egalitarian political systems: https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691195995/against-political-equality

If you are teaching a course on existentialism, I would consider adding a unit on the Mexican existentialists: https://ndpr.nd.edu/reviews/contingency-and-commitment-mexican-existentialism-and-the-place-of-philosophy/

If you are teaching a course on philosophy of ecology or environmental ethics or climate change and sustainability, I would definitely consider having a unit on Indigenous Environmental Studies and Sciences and Kyle Whyte’s work: https://kylewhyte.seas.umich.edu/articles/

So, I don’t think there’s any obligation to go into deep history or any history in courses that are focused on philosophical problems for which there isn’t much of relevance written more than 10 or 15 years ago. But there is a lot of contemporary work that falls under the heading of African Philosophy or Native American Philosophy or Chinese Philosophy etc. that might well be relevant. (There are large meta-philosophical debates about what should be placed under what heading and why; many of the resources mentioned in the main post get into those issues…)

It seems to me that if non-Western traditions have much to contribute to contemporary debates, that implies there’s a lot of low-hanging fruit to be picked up. Given there’s a market in academic publishing (better contributions are more sought after, and make you more likely to get hired) this would suggest that anyone who dislikes the current state of affairs would have a much easier time finding these non-Western contributions than sticking to those that everyone else is, as there’s far less competition. This admttedly seems less plausible when it comes to thinking about historical traditions, where what counts as ‘canon’ arguably is more sensitive to precedent. But when it comes to contemporary topics, it seems that people pushing for more non-Western inclusion need an account of why this purported low hanging fruit isn’t being picked up.

‘It’s in fact really good but you all can’t recognise it because of how you were raised and what you find familiar, so make more of an effort’ isn’t convincing, or at least, misses some really important features. Even if one honestly believes this, and is genuinely curious about new kinds of philosophy, they immediately encounter what I take to be a bigger problem, which is that one can’t identify from the outset which ideas are going to be fruitful and which will have little intellectual payoff. There is no a priori reason to think a certain idea or tradition is useful or true or interesting just because it’s non-western (especially if, again, it would imply there is low hanging fruit no-one is picking up), and more importantly, the ‘it’s good but you just don’t yet recognise it’ response can be made from people defending crackpot theories too, see e.g. random ramblings of various thought leaders. The broader a church we encourage, the harder it is to discern signal from noise, and you can’t insist everything is signal without undoing the entire purpose of having peer reviewed journals. This is also why arguing that people inclined towards the current status quo can’t defend their position because they can’t defensible point to what counts as philosophy risks sawing off the branch we are all sitting on. If there’s no boundaries to what counts, then there’s also no basis for excluding ‘thought leaders’ who commit very basic fallacies.

I take Guerrero to be complaining that we have too many false negatives (philosophy that is in fact good but not identified as such), but any proposed solutions really need to show that they won’t introduce too many false positives (bad ideas identified as good philosophy), which are a far greater problem in the long run. Especially if we collectively begin to admit false negatives from an area simply on the basis that it’s non-traditional, which then brings down the average relative quality of work in that area, which will be eventually noticed by others, leading to a stereotype that work in that area isn’t very good. Favouring ideas encountered from within existing networks, though imperfect, has much more quality assurance, especially if it seems that the assessments of people pushing for change are being motivated by ideological considerations and assumptions that I don’t share, or hinge on arguments implying there is not such thing as quality. Rather than trusting people who insist there is fruit to be picked, and tell me X is fruit that I can’t recognise, I’m more likely to instead wait for specific demonstrations from people who have picked up that fruit and can make others see it e.g. Evan Thompson’s great work on how Indian philosophy contributes to philosophy of mind.

To be clear, I’m not arguing against widening our usual scope or that we shouldn’t include non-western traditions. I’m just saying that arguments in favour of such changes usually somewhat misrepresent the nature of the problem, and that I’m sceptical of solutions which basically amount to collectively agreeing to be motivated by a different set of considerations.

There’s a lot here.

A few quick things.

I don’t know what you have in mind when you talk about introducing false positives, but there are just homerun after homerun works of philosophy that we don’t teach, but which are very well studied outside of philosophy departments in North America, UK, etc. I don’t know what you are picturing, but the idea is not to just include anything everywhere that might fall under the label ‘Chinese Philosophy’ or ‘Africana Philosophy’ or whatever. There has already been a ton of vetting, engagement, discussion, by very careful, serious philosophers. Just not in philosophy departments. So, we’re not flying with our eyes closed. (Just like we aren’t wandering through the stacks of everything that might be labeled ‘philosophy’ that was published in Germany in the 18th century and just picking stuff at random to assign when we teach our Kant courses.)

I’m not sure what you mean by the ‘picking up low hanging fruit’ metaphor. It kind of seems like you mean ‘publishing articles about non-Western philosophical ideas’ or ‘publishing articles drawing on non-Western philosophical ideas’ or something like that. If that’s what you mean, I’m sure you can see an obvious impediment: even if there are great ideas, many leading philosophy journals NEVER publish anything engaging with work from these traditions. Princeton philosopher Harvey Lederman just published an article in Phil Review on the Ming dynasty philosopher Wang Yangming. That was the first research article in Phil Review on a non-European philosophical tradition since 1948, and the first research article in the journal dedicated to the works of a single Chinese philosopher since the journal started in 1892. Phil Review is tough for lots of areas. But the same holds for many, many journals, although the times are changing (albeit slowly).

That said, I absolutely think that there are many exciting ideas that constitute ‘low hanging fruit’ ripe for much more philosophical engagement and discussion. Rather than being the 50,000th person to write about Kant’s ethics in the broadly analytic vein, why not be the 2nd or 3rd person to write about Nzegwu’s discussion of dual-sex governance systems in pre-colonial Igbo society? Write a careful, thoughtful dissertation that contrasts Spinoza’s monistic view with the Aztec/Nahua monistic idea of teotl. Consider how the different elements of Akan conceptions of the person (as debated by Gyekye and Wiredu) might illuminate or contrast with Parfit’s relation-R. Write an article that sets out the philosophically distinctive components of the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace (Kaianere’kó:wa). I think all of these (and millions more) would be absolute bangers and would represent real philosophical contributions. And it would be much easier to be making an interesting and important philosophical advance than by writing the 346th article on quasi-expressivism (no judgment!) or the 1347th article on Rawlsian reasonableness (very tolerant!) or the 568th article on whether knowledge is the norm of assertion (probably not), etc. It might also be easier to publish on those topics, but that’s harder to say, because of the previous point.

Honestly, rather than banging out more pseudo-economic analysis of philosophical progress, I’d encourage you just to pick a few things at random from Van Norden’s bibliography list and start reading. You’ll find lots of fruit, some high up, some low down, some harvested and all packaged up for market, others that you might be the first to have tasted or combined with just these other flavors–all delicious.

Professor Guerrero rejects the justification that “We leave out, or put to the margins, work that is just religion, or anthropology, or literature, or cultural studies, or “thought” that doesn’t constitute philosophy.”

Any of the subject areas listed may be relevant to philosophy and I can see any of them being taught about in a philosophy course, but isn’t there a subject that is distinctly “philosophy”? If not, why have philosophy departments at all? When we ask for money for philosophy, what is it that we say we do?

I’d like to add something to clarify (sorry Justin and thanks as always!)

I appreciate that the boundaries of philosophy are fuzzy and that some work has been excluded in an arbitrary way. I think it makes perfect sense to strive to include relevant work. I think it’s a great idea to look for ideas that have been arbitrarily excluded. I just don’t think that we should get rid of the boundaries altogether.

There is something important in the tradition that we have called “philosophy”, something to do with reasoned argument, offering justifications and considering objections. I can’t offer you a definition that everyone will accept but I don’t want to lose this special thing either.

Some think we shouldn’t have any boundaries at all (or that we shouldn’t spend any time focused on those issues, or policing those boundaries, or…). I’m certainly not committed to anything like that.

My point is that the way work has been included or excluded in telling the standard story is not at all about some faithful, accurate application of some meta-philosophical boundary principle, concerning boundaries between philosophy and religion, or philosophy and science, or philosophy and literature, etc. As I try to stress, the main way in which we can see this is that exclusion of this work has been done without knowing the first thing about it, just assuming (often in an explicitly racist way) that it must be ‘thought’ or ‘religion’ or something that isn’t philosophy.

The ‘something to do with reasoned argument, offering justifications and considering objections’ sounds pretty good to me, but that definitely includes a ton of work that we exclude, including every area I mention in the original post: African Philosophy, Buddhist Philosophy, Chinese Philosophy, Indian Philosophy, Islamic Philosophy, Latin American Philosophy, Native American and Indigenous Philosophy, etc.

And it’s not just like a few things here or there that should have been included. It is completely systematic exclusion of tons of philosophy, and that’s true if by ‘philosophy’ we mean ‘something to do with reasoned argument, offering justifications and considering objections.’

Please forgive the self-promotion:

Steve Phillips and I have been teaching courses and editing textbooks including large amounts of Non-Western material for thirty years. When we started, materials that were clearly philosophical outside the Western tradition were often hard to find; now, it’s much easier. For anyone who’s interested, here are links to books we’ve done. Only the first is still in print.

https://www.amazon.com/Introduction-World-Philosophy-Multicultural-Reader/dp/019515231X/ref=sr_1_4?crid=3AU254ASGC48W&keywords=bonevac+phillips&qid=1654026527&sprefix=bonevac+phillips%2Caps%2C97&sr=8-4

https://www.amazon.com/Understanding-Non-Western-Philosophy-Introductory-Readings/dp/1559340770/ref=sr_1_6?crid=3AU254ASGC48W&keywords=bonevac+phillips&qid=1654026527&sprefix=bonevac+phillips%2Caps%2C97&sr=8-6

https://www.amazon.com/Beyond-Western-Tradition-Political-Philosophy/dp/1559340754/ref=sr_1_9?crid=3AU254ASGC48W&keywords=bonevac+phillips&qid=1654026527&sprefix=bonevac+phillips%2Caps%2C97&sr=8-9

There are also some videos that cover Non-Western thinkers on my YouTube channel. Many of the videos on traditional philosophical concepts include references to both Western and Non-Western works.

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLzWd5Ny3vW3Twa6jGRRBYsrqsLodJYfG7

Allow me to set aside history of philosophy considerations and focus on live philosophical debates. Are there ideas—present or historical—from outside of Anglo-European philosophy that would contribute to contemporary debates? I presume so and the philosophy of this audience would be the better for including them. As such, journals should publish (that is, philosophy should incentivize) articles that retrieve these ideas. In other words, there should be an exception to the originality requirement for articles to include “original to this audience.” This would fast-track getting these ideas into the system. (Ideally, these ideas would be written as the author’s own for blind review purposes but that seems infeasible.) A journal with precisely this mission might be low-hanging fruit. However, insofar as any material cannot stand on its own outside of its identification as a particular [ethnic/regional] philosophy, then it seems a matter only for historians of philosophy and history of philosophy classes (none of which should be required by the way—you should read Kant’s Critique in Epistemology not some historical class). (Also, we should all have been posting in Esperanto by now.)

When first taught Kant’s ethics, students often ask about how it relates to the golden rule. Professors are typically well-equipped to explain why the categorical imperative is not the same. This helps many students better understand Kant. Thousands of undergrads in the US each year (at least ones with a South Asian background, but I’m guessing many others too) can’t help but also notice the resemblance between Kant’s ethics and Krishna’s Gita in the Mahabharata. It would be great if their professors didn’t draw a blank, when asked about this resemblance—quite apart from the value of studying the Gita, I’d imagine it would help students develop a more nuanced understanding of Kant.

My point here is not about adding more non-western thinkers. But rather, even with respect to helping students understand western thinkers it helps to be able differentiate the views from nearby views students might already be familiar with. Sometimes these nearby views are going to trace back to thinkers outside of the western canon.

For what it’s worth, see S. Radakrishnan’s, “The Ethics of

the Bhagavadgita and Kant” published in 1911 in Ethics (at

the time, “International Journal of Ethics”):

“Much has been made of the apparent similarity between the ethical

systems of the Bhagavadgita and Kant, the critical philosopher. To the

superficial reader, the similarity is no doubt striking. Both systems preach against the rule of the senses; both are at one in holding that the moral law demands duty for duty’s sake. In spite of the agreements between the two systems, however, sober second thought will disclose differences of great moment.”

This makes me think that maybe I should re-read the _Bhagavadgita_, which I haven’t read since I read it for an undergraduate “Asian Philosophy” class many years ago!

So have you read much Islamic philosophy? That would be a necessary condition of recommending it to someone else.

I have read some of both Al-Farabi and Avicenna.

But I also dispute that a necessary condition of A appropriately recommending X is that A has read X. It might also be that A trusts B, and has excellent reason to trust B, and one knows that B has read X and that B recommends X.

In this case, I would recommend to everyone interested in Islamic Philosophy one truly excellent B, Peter Adamson, whose podcast does an amazing job introducing a wide array of Islamic Philosophy: https://historyofphilosophy.net/series/islamic-world

If you aren’t a podcast person, much of the content has now been published by OUP: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/philosophy-in-the-islamic-world-9780199577491?q=peter%20adamson&lang=en&cc=us

I am not a specialist in any of these areas, but I am learning, and by the end of next year I will have taught African, Latin American, and Native American Philosophy and Introduction to Chinese Philosophy. After several more years of gaining competence and taking up some research in those areas, who knows, I might add Intro to Islamic Philosophy as well. Keeps things interesting!

I’m pretty interested in Russian philosophy, both pre-Soviet and some Soviet stuff. Interestingly, this work is almost never covered in US philosophy departments, and is also almost never mentioned in discussions like this one. (The last time I looked, it was a giant “gap” in the “History of Philosophy with no Gaps” project!) (In grad school I wanted to fulfill my language requirement by taking some Russian classes, to get my very slow reading speed up to a more workable level, but was told I could not because “there was no tradition” to work on. That wasn’t true, but it’s a very common belief, and it didn’t seem worth fighting over. Instead I satisfied my requirement by not actually learning enough German to do me any good.)

But, despite my interest in this stuff, with one very small exception (co-authored and largely discursive), I’ve not written anything on Russian philosophy, and rarely mention it in my work. Why not? Because it’s hard work, often is addressed to topics than are different from those I’m mostly writing on, and doing it very well would be quite time consuming, taking me away from work that’s likely to have larger career pay-offs (for reasons both good and bad.) I have taught a little bit – of Kropotkin, in a criminal law theory class, to law students – with some descent success. And, it would be fun and interesting (and maybe even useful for other people) to be able to spend more time on this stuff. But it would also be very bad for me professionally. No doubt there’s a collective action problem here, but such problems are, by their nature, not ones that most individuals can address on their own. I suspect that similar things apply for others who are not already very comfortably situated in more or less the exact job they want.

(the short piece mentioned can be found here: https://www.academia.edu/1757103/Philosophy_in_Russia If I were approaching the subject today, I’d emphasize different things, but maybe it’s still of some use to some people.)

Yes, I actually considered mentioning Russian Philosophy by name (maybe thinking about past conversations we’ve had?)! I instead just went with the very first parenthetical, partly because there actually are quite a few other arguably ‘European’ or ‘Eurasian’ philosophical traditions that also are left out, with a host of meta-philosophical questions about how to draw various boundaries…

It’s definitely true that taking these things on is easier to do once one has a lot of job stability/security. I hope at some point you’ll be able to design and teach a Russian Philosophy class!

You could switch to Igbo philosophy, medieval Thai Buddhist or Serbian philosophy in 18th century and walk the talk! I mean – really do it, do something that is actually different, learn the languages and found a new direction for US academic departments, independently of what the current or one’s own or preferred by current culture demographics demands – which is, after all, the wrong way to go since that is how the current status quo came about. How about that?

While I largely agree with the goal of this article, I think it leaves out some of the systemic hurtles embedded in academia. It can take a lot of time to sincerely improve knowledge in another tradition so that an entirely new course can be taught. If one has tenure, then one isn’t at risk of losing their job unlike someone who does not have tenure. To get to that point, one will need to publish in their field of expertise which is already likely western philosophy. So the systemic incentives need to change. The publish or perish model, that capitalist model of academia, must end.

Yes, I very much agree that people at different career stages and at different positions in the field will be able to take up different parts of this.

My dissertation and all of the research that helped me to get a job and then to get tenure was on contemporary moral and political philosophy unrelated to any work from these excluded philosophical traditions. I had interests in some of these other areas going all the way back to my undergraduate studies, but it wasn’t until I felt secure in my path toward tenure that I took up the project of creating a new course, and I didn’t begin teaching it until after I received tenure.

I do think some of these incentives are changing. As I noted in the post, there are starting to be many more jobs advertised in these areas, and there still are very few programs producing students working in these areas, so it’s not clear to me it’s professionally disadvantageous to have research strengths in these areas. And in many places, there is high student demand for courses in these areas, so it would be advantageous to be able to teach those courses.

But it’s certainly true that one must pay attention to one’s local situation and do what one can in light of those constraints.

A couple thoughts:

1. While perhaps it’s clear that the predominant story of philosophy in the West is “overwhelmingly male”, I don’t think it’s clear that this story is “overwhelmingly white” on /any/ of the prevailing definitions of ‘white’, at least if we include pre-early-moderns, as the predominant story does.

2. I grant that your two “broad families of answers” to your opening questions (“Why is this the story that has been told, over and over again, to undergraduates moving through philosophy programs? Why is this the story that we continue to tell through our major requirements and PhD distribution requirements?”) are accurate and exhaustive–these are the two main options. However, you then argue that the first family or “kind of answer” “claims that, in sticking to the story above, we teach and require everything that is most centrally well-described as philosophy. We leave out, or put to the margins, work that is just religion, or anthropology, or literature, or cultural studies, or “thought” that doesn’t constitute philosophy.” Note that this is only one way of giving the first kind of answer, but, as your post admits or implies at many junctures, there are many other ways of doing so. For instance, it may be that (most) Western philosophers are qualified to teach only the tradition with which they are familiar, believe they ought to teach what they are qualified to teach, but grant that there are other traditions that qualify as philosophy. You touch on this sort of view later on, but it isn’t included in your first family as you describe it in your opening argument. This is not to defend this way of giving the first answer, but it is to say that it’s not clear why we should think that you are justified in narrowing as severely as you do the option space available to those who take the first option.

3. More effort should be put into figuring out how Western philosophers might justify why they tell the predominant story as they do. Jumping so quickly to debunking stories about how it’s natural to “feel defensive and protective of what you have come to know and love” seems beyond premature. Debunking stories this general and weak are a dime a dozen–we can tell parallel stories about many of those who are currently promoting changes to the predominant story–and they often just obscure or prevent authentic and open dialogue.

4. It’s not clear to me why wider historical and geographical coverage in philosophy story-telling is valuable in itself. I can see why it is troubling to represent a narrow subset of philosophy as /philosophy/, but, again, I don’t think many people actually would take this line (per the above). I can see why it is not good to ignore relevant evidence for viable answers to philosophical problems in general…and thus that provided by other traditions (this is a version of your final “main reason” at the end of your post). Etc. Granted. But it’s hard to see why merely broader coverage is valuable in itself. And even if it is valuable in itself, achieving broader coverage comes at significant costs in other similar values that are not being addressed here with any seriousness. Perhaps this comes down to a disagreement about what the primary goal of a philosophy department should be, which is one of your concerns, I take it. I think it’s clear that it’s not /primarily/ about representing philosophy as a global and timeless whole accurately. Why should we think it is?

Thank you so much for the original post, for all of the work behind it, and for the comments, Alexander. There’s an impressive amount of intellectual, social, and emotional labor there!

I’ve also appreciated the discussion in the comments. It’s cool to see folx resourcing and pushing each other in these ways.

PhiloHawg—I take your providing mostly criticism in concise, numbered points as reason to believe you appreciate direct criticism as a form of engagement at times. I do too. So, in that reciprocally-critical spirit, I want to be honest that I felt like your contribution lowered the level of collaborative exchange, intellectual responsibility, and willingness to listen to understand.

I want to engage your individual points to try to give a sense of why I felt this way in the hopes of getting us back in some alignment:

(1) You say that there’s no prevailing definition of ‘white’ which would make the following sentence true: “the story of philosophy in the west is overwhelmingly white”. Especially if we’re listening to understand and applying a principle of charity, there are numerous ways of understanding ‘white’ that scholars and activists of race would argue give a true interpretation of the sentence. My guess, though, is that you’re implicating that all prevailing definitions of ‘white’ take some central notion of race to be a clearly modern phenomenon, such that people only become white (or Black or Indigenous or AANHPI or Latin@ or MENA) in the modern period. I actually tend to adopt and have argued for a particular type of social constructionist view which would agree with that. That said, there’s lots of accounts of race, racism, and whiteness out there that argue that these apply prior to the modern period. As Charles Mills (rest in peace, rest in power, rest in love) points out in one of his last papers (a brilliant one that everybody ought to read on five different ways of reading Locke on slavery),

“until a few decades ago a strong scholarly consensus existed that racism was a product of modernity. Ethnocentrism, religious bigotry, xenophobia, all existed in pre-modernity but not racism because the concept of race had not yet been invented…But in a recent wave of revisionist work initiated by Benjamin Isaac’s 2004 The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, a growing number of theorists are contending that this scholarly consensus is quite wrong. For Isaac and at least some other supporters of this longer periodization, Aristotle should be seen as the pioneering racist theorist of the Western tradition.” (Mills 2021, p. 488)

Furthermore, Geraldine Heng has done really cool work on race and racism in the European middle ages, especially in her book, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. In a separate direction, that I would endorse, the STORY of philosophy in the West could be overwhelmingly white even without it being true that most of the individual philosophers from the story are white (because they lived in pre-modern, pre-racial times). The thought here could be that the story is white in the sense of being a part of structures of white ignorance, white supremacy, white silence, white collusion, etc. A very natural way to do this would be to look at a genealogy of the modern story (canon) of philosophy, like Peter KJ Park’s fantastic book, Africa, Asia, and the History of Philosophy: Racism in the Formation of the Philosophical Canon, 1780-1830. This shows that histories of philosophy up until the middle of the 18th century were overwhelmingly much more diverse than even our own today. The vast majority of historians of philosophy up to this point not only included much more focus on different philosophical traditions from Africa and Asia, they also took one or the other of these continents to be the birthplace of philosophy and sources of influence for the Greek philosophers. Then, a group of racist philosophers, historians, and anthropologists, like Christoph Meiners, Dietrich Tiedemann, Wilhelm Tennemann, and Immanuel Kant, gave white supremacist recharacterizations of the history of philosophy for largely racist reasons. This seems to me to make it true that there’s a sense in which the canon of philosophy can be called ‘white’, even if it isn’t accurate to call Socrates or Plato or Aristotle ‘white’.

(2) I read Alexander’s point much differently than you did, PhiloHawg. I read Alexander’s point in a collective sense and I think you’re reading it in a more individualistic sense. The types of justification and vindication that Alexander was talking about were all put in terms of ‘we’. That is to say, what is being sought is a justification for us deciding to continue to tell the story of philosophy, to present the canon of philosophy, in the ways we currently do. The types of justification you’re pointing to would be an individual faculty member justifying their continuing to teach the story they’ve been taught. An individual faculty member could think they were justified in teaching that story without thinking that what we’re doing as a philosophy department, discipline, community, etc. is in any way justified or vindicated.

Furthermore, it seems to me like part of what Alexander did above was give, and point to, reasons that would override their desire to teach only the tradition with which they are familiar. Or, another way to read Alexander could be as giving reason to think that one couldn’t all-that-reasonably hold on to an unrestricted principle that they ought to only teach that tradition with which they are currently familiar. After all, it turns out that almost all of us are familiar with what we are for largely oppressive and unjust reasons. On top of that, part of the point seems to be that the story of philosophy, the canon we present, doesn’t even familiarize us with a tradition. Lots of critical theorists of race and gender over the last handful of decades have shown that folx interested in western and anglo-european and anglo-american traditions miss out on a lot of the potential of those traditions with the standard story which leaves out Anton Wilhelm Amo, Quobna Ottobah Cugoano, David Walker, Maria Stewart, Antenor Firmin, Martin Delany, Frederick Douglass, Anna Julia Cooper, Luisa Capetillo, Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. DuBois, George Wilmot Blyden, James Baldwin, Walter Rodney, Angela Davis, Audre Lorde, and more. I’m thinking of writings by Charles Mills, Lewis Gordon, Dwight Lewis, Myisha Cherry, Kathryn Sophia Belle, Liam Kofi Bright, Stephanie Rivera Berruz, Darryl Scriven, and more.

(3) I’m very surprised by your suggestion that there hasn’t been effort put into figuring out how western philosophers justify why they tell the predominant story as they do. I would take it that Alexander shows some of that effort in this thread and gives resources to see much more of that effort. Similarly, others have added resources in this thread to see further efforts and I hope to have provided a few more resources to see even more efforts here. On top of that, I’ve done some work on this front myself. From a lived experience perspective at the APA Blog, Where the Hell Have Us White Philosophers Been? The Need for Peace, Love, and Racial Justice in Philosophy . From a more theoretical perspective, Race, Gender, and the History of Early Analytic Philosophy . In podcast form, The Question of Inclusion in Philosophy , Baldwin as Juneteenth & Pride , Open the Books , Black Masculinities: the super predator-not , A Counter Narrative using Non-western, Anti-western, and Other-western Philosophers and Philosophies , Rage & Social Justice: A New Beginning , and Black Planetary Ecology: Diamonds in the Cave .

So, again, Alexander seemed to me to be anything but premature in going to an explanation of defensiveness and protectiveness of what we’ve come to know and love. Rather, he seemed to me to be being a best-and-highest-self charitable reader. Because, as the above shows, the alternative explanation is intentional complicity in racism, white ignorance, and the like. Alexander seemed to be assuming that folx have good intent and aren’t intending to have such an impact—they simply have that impact as a result of systemic ignorance combined with an inclination to respond in protective ways to challenging what we’re used to. My own efforts to understand this defensiveness have been to see this as significantly located in the body. We need to understand this in terms of trauma and trauma responses—in particular, racialized trauma. I think we cannot have authentic and open dialogue without recognizing these bodily phenomena and tendencies that encourage us to take certain cognitive stances—not just in people I disagree with, but in myself and my comrades as well. Folx interested in this should look at the work of scholar-practitioner-activists like Ruth King https://ruthking.net and Resmaa Menakem https://www.resmaa.com .

(4) I genuinely just don’t see where Alexander suggests that “wider historical and geographical coverage in philosophy story-telling is valuable in itself”. I certainly see that he suggests “wider historical and geographical coverage in philosophy story-telling is valuable”. I just don’t see where the “in itself” piece comes from. Alexander seems to be taking a very naturalistic, practical, and empirical approach to philosophy and pedagogy. He isn’t so much focused on ideal theoretic arguments about what we do in principle or what’s valuable in itself. The point is that, given the actual world we live in, the institutional policies, practices and protocols in place, and the cultural narratives, standards, and myths at play, it will always be prudent for us to take a wide historical and geographical approach to story telling in philosophy. Given what we know about how the current Eurocentric canon was created, we should absolutely move away from the standard story. That this is how Alexander would be oriented shouldn’t be surprising when we understand the role of ideal theory and non-ideal theory in ideology construction and deconstruction (again, see the wonderful work of Charles Mills).

Again, this was offered in the spirit of Baldwinian love, where “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within” and where “if I Love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see.” I hope you’ll reach out if you want to engage more.

Hi PhiloHawg; I just want to say I disagree with this in Matt LaVine’s reply to your post:

Thanks for the feedback, Preston! Although ten years of interacting together is starting to make me think you can just put a negation sign in front of my views to get yours and vice versa! Haha

Indeed, Matt. Though I’m enough of a Peircean optimist to think we may eventually see eye to eye, and sufficiently Sellarsian to suspect we would, even now, agree about more than we realize if we had the right language. Hope all is well.

I appreciate the intellectual and personal hopes, Preston! Hope you’re taking care of yourself in these difficult times!

Thanks for the post Alex. An addition suggestion for things we can do individually to bring about a more diversified view of philosophy is to incorporate corresponding discussions elsewhere in our professional lives– for example, in departmental talks, at conferences, in inter-institutional committee work, in article reviewing. The focus on teaching and what is taught, as well as PhD education and focus is important, but to be really effective this perspective on philosophy needs to find its way into all aspects of the broader philosophical culture. That too requires disrupting business as usual and some additional work on the part of each of us when we find ourselves with an opportunity to introduce some lesser known sources or raise some largely unasked questions.

I approach this much like I have philosophy for children over the past nearly 40 years: get people thinking constructively about it whenever you can, even when its not the focus of discussion. In both case, students at all levels are especially receptive to hearing about these alternatives that lie beyond what they have been exposed to (or exposed to less) in their philosophical education.

On this topic, I’d like to shamelessly plug an upcoming textbook I’m editing. It’s on ethical theory, covers a range of non-Western views (Indian, Chinese, Japanese, and African) in addition to the usual suspects in Western ethics, and tries to put them all into conversation in a meaningful way. Most importantly, it’s highly accessible and should be able to be used in the run-of-the-mill kind of ethical theory course you find in most departments, and taught by faculty with little to no background in non-Western philosophy.

Hopefully it should be out with SUNY Press in the next year or so, so if it sounds like something you’d be interested in, keep an eye out for it.

Excellent! I look forward to seeing it!

I think this is mostly very helpful and insightful. I will raise my usual concern, though: a significant part of modern philosophy – the part that is in close dialogue with contemporary science and mathematics – isn’t really part of any specific philosophical tradition. That covers at least the philosophy of the specific sciences and most of formal logic; it probably extends across most of general philosophy of science, and the more formal parts of epistemology and the more science-adjacent parts of mind and language, though there’s room to debate the exact boundaries.

I don’t think Prof. Guerrero would disagree and I don’t read his post as doing so. (His reply to ‘Caligula’s Goat’ makes that explicit.) But I do think some of these discussions either elide science-based philosophy entirely or – worse – treat it as ‘western philosophy’, and in doing so inadvertently support the disastrous and pernicious message that science is ‘western science’.

That said, I think philosophy of science can also benefit intellectually from a broadening of the canon of historical philosophy. I don’t myself spend a lot of time reading historical philosophy – in any tradition – because it’s hard to justify the time cost when there is so much physics and math to keep up with, so I benefit a lot from colleagues in more mainstream areas of philosophy who can tell me what to look at and what insights to gain. I absolutely welcome those colleagues (individually or collectively) having a broader range of historical traditions to draw upon.

With apologies for the double-posting: on reflection, I think the existence of the historical-tradition-neutral part of philosophy actually strengthens the case for the sort of diversification Prof. Guerrero advocates. I don’t actually think there would be anything wrong with a university – especially a European university – offering the chance to major in the history of European philosophy and having a department of European philosophy that taught that major. But it’s hard to make a good case for a department of (History of European philosophy plus modern analytic philosophy of science) – unless that case is based on a normative assessment of the European tradition being just objectively better, which I find pretty implausible for broadly the grounds the OP develops.

Regarding the MLK syllabus: Augustine was from North Africa, and it is Augustine’s view that an unjust law is no law at all (i.e., an unjust law has no real normative authority over us) that MLK appealed to when justifying civil disobedience in the Letter from Birmingham Jail. In making this comment, I am not suggesting that Alex is wrong when he says that the philosophical canon in the West is overwhelmingly white, male, and European (where “European” includes English, Scottish, Australian, and US-American). No doubt it is. But still, the point about Augustine is worth keeping in mind. (Although Alex did not say that MLK’s syllabus was all dead white men, I do think that many people reading Alex’s post would naturally infer that MLK’s syllabus was all dead white men. And that inference is false.)