Conference Series On Oppressive Speech Disinvites Trans-Exclusionary Philosopher

Leibniz-Zentrum Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft (ZAS), a publicly-funded research institute in Berlin that is holding a series of conferences on oppressive speech between now and May, has removed a philosopher from its program after complaints about her planned talk.

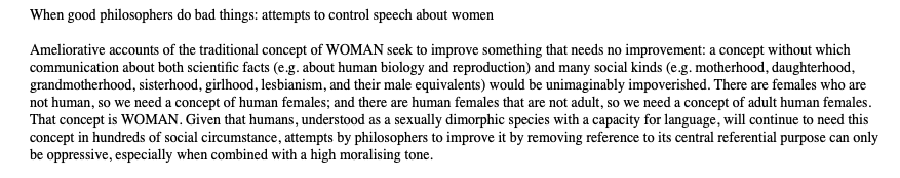

The philosopher, Kathleen Stock (Sussex), had been invited to particpate in the session taking place in April, 2021, the theme of which is “Gendered Speech Acts, Practices, and Norms.” Stock’s planned talk was of a piece with the trans-exclusionary position she has advocated for over the past few years on social media and in Medium posts, Quillette, The Economist, and elsewhere:

According to Leiter Reports, which first reported on this story, another philosopher taking part in a different session complained about Stock’s participation in the conference, and because of this, says Stock in a tweet, she was “told to withdraw.”

ZAS itself said in a tweet:

ZAS had to retract the abstract because it did not fit to the scientific theme of the workshop (oppressive speech & communication) and contained language that was inconsistent with the values of the ZAS. We regret that the abstract went online.

What to make of these two reasons?

Regarding the first: As advocates of the trans-exclusionary view like to note, their view is the dominant one in the broader culture. So in simply reinforcing the hegemonic trans-exclusionary conception of “woman,” Stock’s paper could be seen as closer to exemplifying what some take to be “oppressive speech,” rather than taking up oppressive speech as a topic. That said, it is highly unusual for such a degree of scrutiny to be applied to invited talks, after the speaker has been invited, with a consequence of such scrutiny being that the speaker is disinvited. Though still unusual, it would have been much more respectful and sensible to consult with the speaker about revising her paper or giving a different one if the proposed one really did not fit the conference at which the speaker was invited to speak.

Regarding the second: This seems more straightforward. Stock is arguing for a trans-exclusionary view, and ZAS presumably takes that to be inconsistent with its values.

OK, ZAS, you’re within your rights to not want to be identified with trans-exclusionary views. And sure, you’re within your rights to disinvite a speaker. But you didn’t have to. This is because, for one thing, inclusion needn’t imply endorsement (though see here, too).

For another, if you oppose trans-exclusionary views, and you would like others in the academy to oppose them, too, then sometimes we’re going to have to hear such views. As I wrote last year:

The more I have learned about the philosophical and policy arguments regarding transgender issues, and in particular trans women, the closer I have come to a fairly strong trans-inclusive view. Like most philosophers, I’m not the kind of person who, on controversial matters, just takes others’ words for it. I want to hold the view of the matter that I believe is most justified, and to do that I need to understand the issues and to be moved by reasons and arguments, and to do that well, I need to make sure I’m getting a good accounting of the relevant considerations and opposing arguments. How can I do that? By engaging with the best work those with competing views have to offer.

If the institutions of philosophy prohibit the defense of trans-exclusionary views, what then? Do the views disappear? No. Rather, their best defenses go elsewhere, to less reliable, less seriously-vetted venues (think, for example, of Quillette, or blogs), where argumentative errors, rhetorical nudges, strategic omissions, and polemical sleights-of-hand are more likely.

Furthermore, the absence of trans-exclusionary views from academic venues under such conditions does not thereby signal their weakness to philosophers who’ve yet to form considered opinions on the matter. It signals instead a kind of dogmatism that threatens to alienate allies…

In short, if your interest is in more philosophers coming to reject trans-exclusionary views, then we have to talk about trans-exclusionary views, and to do that well, we have to let those with trans-exclusionary views talk to us through the institutions we’ve found valuable for pursuing the truth. This argument doesn’t depend on prioritizing philosophical questioning above all else, or on the idea that as philosophers we question everything. It is based on a confidence in the justifiability of a more trans-inclusive view, and a belief that Millian considerations regarding the expression of ideas are not unrealistic for the philosophical community.

Additionally, to say that we have to let those with trans-exclusionary views talk to us is not to say that everything goes…

Or, as Elizabeth Barnes (Virginia) said last year:

I think we need to take seriously the pain and harm that can be caused to individuals by philosophical arguments. What is a purely hypothetical thought experiment for one person is a discussion of someone else’s personal suffering, and I think that discrepancy matters. Nor do I think all arguments are worth taking seriously—sometimes the moral awfulness of an argument’s conclusion can make me think that it’s not worth engaging, no matter how clever or interesting the premises might be. The question then is when to engage, and for me that is just a hard question with no clear answers.

At least for my own decisions, one thing I think about a lot is whether the argument is taken seriously in wider public discourse. (I know people worry that engaging with offensive arguments will ‘legitimize’ them, but in a lot of cases the arguments already have widespread currency, and whether I pay attention to them won’t change that.) I’m the elite among disabled people—I have great health insurance and a full-time job with great job security. And I also, in an important sense, make my living and my reputation from talking about the experiences and the oppression of people less fortunate than I am. So if I then turn around and say, in response to an argument that has wide public currency, that it’s too offensive for me to engage with, that doesn’t strike me as fair. What am I here for if not to philosophically engage with arguments that are hurting people who are subject to the type of oppression I study (the study of which gets me a nice paycheck and invitations to fancy universities and etc)?…

Another thing that matters to me a great deal, when thinking through these issues, is what happens to philosophical discourse if we repeatedly say that arguments or positions ought not to be entertained because they are offensive or politically unacceptable. I should caveat by saying that I think that a lot of complaining about free speech and no-platforming is overblown, especially because in many cases we adopt a ‘teach the controversy’ mindset in which arguments are given prominence not because they are particularly interesting or challenging, but simply because their conclusitons are controversial. And then the same people are asked, over and over, to engage with these arguments in a way that can feel more like public theater than genuine philosophical engagement. And I can understand getting sick of that. That being said, I am genuinely concerned about issues of political censorship in philosophy.

And I’m concerned not because I think we have to make sure we protect the rights of obnoxious people to say obnoxious things (although I do think that.) I’m concerned because academia, like most any other social setting, has embedded hierarchies and power structures. If I was confident that the progressive elite of academia would always be on the side of right, then I wouldn’t be too worried about a norm of discourse that says you can shout down views that you find offensive or that you are politically opposed to. But I’m not confident of that. In fact I’m very confident of the opposite. And so I think it’s imperative, if we want to protect the ability of the truly vulnerable to be heard and to question consensus, that we have a norm of allowing views that go against the political grain. This will, of course, involve having a norm that allows for shitty and offensive views. But I think that’s a price worth paying.

Whether it’s justifiable or not, we take there to be a difference between not being invited to an academic event and having one’s invitation to it rescinded—no one will notice the former but people will make noise about the latter. If Stock wasn’t the right fit for your conference, or you weren’t prepared to responsibly put on a talk by someone whose views you think are at odds with your values, then you ought not to have invited her in the first place. But you did, and now you’ve disinvited her, you handled it badly, and now there is, reasonably, some noise.

* * * * *

Readers, I’m going to try to leave comments open on this. If you want to comment on this thread, you’ll have to use your real name to do so. Please be patient. Comments may take a while to appear (I have grading to do and a few meetings today).

It would be great if the discussion were useful, say, by focusing on ways events can include views the organizers reject without endorsing those views, or what steps, if any, event organizers could usefully take besides disinviting a speaker when they find themselves in a position like ZAS’s, or ways speakers could effectively and respectfully present offensive ideas, etc. And of course readers are welcome to disagree with my views about speech presented here. But here’s what I don’t want comments on:

- Why I call Stock’s view “trans-exclusionary,” and whether I should call it that (see here)

- Whether Stock’s view is correct or not.

- What kind of person you think Stock is.

- Whether trans women are women, whether trans men are men, and generalizations about people who are trans.

- Outing specific people as trans.

- How I’m censoring you.

- If 2+2 = 4

- The supposed irony of this list on a post about someone losing an opportunity to speak.

Thank you for your cooperation.

UPDATE (12/18/20): Comments on this post are now closed.

Related: “When Tables Speak”: On the Existence of Trans Philosophy

I would’ve expected philosophers to be better at tolerating views that are contrary to their values. For example, did you know that some philosophers have defended eating animals? Others have defended sitting by and doing nothing (or very little) while children in other countries literally die from entirely preventable causes (e.g. malaria). Those views should surely be “contrary to our values”, if any are. But we don’t bat an eyelid at them — and rightly so!

On Justin’s first point (whether Professor Stock’s paper can’t be regarded as taking up oppressive speech as a topic given that the view supposedly being oppressed is ‘the dominant one in the broader culture’): it would be really strange to suppose, with a level of confidence sufficient to retroactively reject a paper, that speech can’t be oppressive in some subculture unless it would be oppressive in the broader culture. And a quick perusal of the abstracts for the conference series – especially Theme 5, the one where Professor Stock was to be speaking – shows that many of them are concerned with putatively oppressive speech within certain subcultures, rather than in the broader culture. So I don’t find this persuasive.

On Justin’s second point (whether retracting a paper is okay if it’s retroactively judged to have ‘language inconsistent with the values’ of the organisers: Justin’s eventual conclusion is ‘no, it’s not okay’ and of course that’s correct. But I think it says something concerning about the current norms in the profession if this conclusion needs an 1,100-word apologia and not a one-sentence condemnation on straightforward academic-freedom grounds.

I think Dr. Stock, who has written on objectification and sexual orientation, would be a perfect choice for a panel on oppressive speech based on gender or sexual orientation, but it kind of seems bad form for her to present a paper about oppressive speech directed toward the trans community, since many consider her to be an instrument of that kind of speech.

“Oppressive” is far from a neutral frame for the conference. I take it that an “oppressive speech”-themed conference focuses on combating it and its effects, not on whether or not an oppressed group is *really* or *rightly* oppressed. One wouldn’t expect to see someone accused of using racist speech on a panel about *oppressive* race speech.

There may be appropriate panels for Dr. Stock’s views on transgendered people (though, I’m a little skeptical there is), but this one doesn’t seem to be it, given its theme.

This is a reply to Wes McMicheal, who wrote:

“One wouldn’t expect to see someone accused of using racist speech on a panel about *oppressive* race speech.”

I don’t find that so clear. E.g., I don’t think Harvard Law professor Randall Kennedy would be at all a strange choice for a panel on oppressive racist speech. But given his book, subtitled “the strange career of a troublesome word”, I’m sure he’s been accused of using racist speech.

Omitted in your story is the fact that Professor Stock was originally invited to participate in a session called “Bodies, Gender Identity, and Misogyny”; ZAS changed the title after disinviting her.

Second, the ZAS tweet says that Stock’s abstract “contained language” inconsistent with its values. Whether ZAS meant to say that the problem was with the abstract’s terminology, or rather with the views expressed by the abstract, is unclear. More importantly, this appears to be some feeble attempt at a retroactive justification after Stock was removed because another philosopher complained.

Third, commentators on this post are instructed to ignore whether Stock’s view is true. But this is relevant to the question of whether ZAS “ought…to have invited her in the first place.” Naturally organizers of an academic workshop on philosophical topic X will try not to invite speakers who have silly or poorly-argued views on X. But what about speakers who have well-argued views on X, which happen to conflict with the views or values of the organizers, or which some people find offensive? Unless philosophy is a joke, that is no reason at all not to invite such speakers.

Fourth, either ZAS’s values are inconsistent or their policies are. One of the talks is by Louise Antony, a defense of “the value of freedom of speech.” (Good for Professor Antony, I should add!) If this conflicts with ZAS’s values, they don’t seem to be doing anything about it.

It seems problematic to close a rational discussion of a topic because it might result in emotional pain. Doing that appears to serve the manipulative function of an Appeal to Emotion argument.

We may not have a clear view what is at stake where offensiveness, fragility, and the personal significance of philosophical topics are concerned. These factors have been far more widespread and relevant for far longer than the discussion about trans. For instance, in taking a philosophy of religion class, a Christian student has to hear and treat seriously the idea that the most important beliefs, emotional states, and personal relationships of his life are the constituents of an embarrassing or even morally compromising delusion– other people in the class will be arguing that. Likewise, an atheist has to hear and take seriously the idea that she is fundamentally alienated from the only source of value in the universe and may be in for hell– other people in the class will be arguing that. Of course, they do not direct their arguments personally, but the implications are clear to anyone really thinking about the issue. These are not the only topics of similar personal significance.

If we want to be able to keep such discussions central to philosophical practice, we may have to take it for granted (a) that people are responsible for engaging in or tuning into arguments about personally significant ideas only if they are robust enough not to be damaged by associated negative emotion, and (b) that to the extent that participants are moved to change their perspective (even on the moral worth of their own mode of life: e.g. with believers and atheists), this is one of the features of these kinds of conversations, not a bug.

This is a reply to Wes McMichael, who wrote, “[I]t kind of seems bad form for her to present a paper about oppressive speech directed toward the trans community.” However, my understanding is that this paper is not about oppressive speech directed toward the trans community. It is about oppressive speech directed towards women.

Molly, I thought the photo Justin attaches to the article was the abstract of her paper, which seems directed at trans women. Is that incorrect? If so, I retract my statement.

The “reply” button isn’t working for me, but this is a reply to Wes McMichael. Are you saying that the paper is “directed at” trans women, or are you saying that the paper is about oppression that is “directed at” trans women? I don’t think either interpretation is quite right. As I understand it, the paper is about how speech (or attempts to control speech) can oppress women.

This comment is a reply to Molly and Wes,

I think the paper is bidirectional. It’s a fact of genuine epistemic conflicts that the constituent positions are mutually exclusive, so an attempt to gain ground in such a conflict is likely to be conceivable under the aspects of defense and attack. Stock presents herself as defending women from an attack by her counterparts in this epistemic conflict (not trans-people as such: it seems possible to be trans and be even sympathetic with the trans-exclusionary position). However, to the extent that she is successful in persuading the public, she will be seen (at least by some) as limiting the degree of public self-realization trans-people are capable of. So, the social/epistemic valence of the paper is bidirectional.

A significant question that lurks under this issue of the social/epistemic valence of the paper is how to understand ‘epistemic violence’. I feel an assumption under this brief exchange that the issue is that ‘epistemic violence’ is being directed at somebody, and whoever is doing it is in the wrong. But what exactly is epistemic violence, and if it is in part just personally and socially significant argument, then isn’t it justified in many cases? How do we distinguish between genuinely oppressive speech (a la– in the extreme– 1984) and ‘oppressive speech’ as Russel conjugation for personally and socially significant argument?

@Matthew Capps:

“How do we distinguish between genuinely oppressive speech (a la– in the extreme– 1984) and ‘oppressive speech’ as Russel conjugation for personally and socially significant argument?”

It’s a while since I’ve read it, but I recall that the typical oppressive speech act in 1984 was of the form “Do this thing” or “Behave this way”, and what made it oppressive was that if you didn’t do this thing or behave this way, you were kidnapped and tortured by the Thought Police. Big Brother didn’t need epistemic violence, the regular kind of violence worked fine for him.

I am generally opposed to inviting propagandists to speak on ethical topics in an academic venue. Doing so makes a mockery of the intellectual values that academics and especially philosophers ought to value and promote. But were my own department, for example, to make a mistake and invite a propagandist to speak, I would be the last to urge my colleagues to withdraw the invitation. And I would adamantly oppose withdrawing an invitation on the grounds that the invited speaker’s views were offensive. That would clearly violate academic freedom, and would be likely to amplify the disinvited person’s voice as a consequence of the publicity generated by what will accurately be described as censorship and silencing. This is not to say that there are not many kinds of cases when the presumption against withdrawing an invitation is overcome. Suppose a colloquium committee, for example, invites someone and then learns that the invitee once behaved in an extremely offensive way to a member of their department. Depending on the details, withdrawing the invitation might be appropriate. As one of my philosophy professors used to say, there are cases and cases.

I may be old fashioned and idealistic in this respect, but I would suggest philosophy functions in a dialogue in a context where truth stands as telos, good intentions are the norm, and where reasons and evidence are openly contemplated. Hard to see that here. The feelings and suffering of the interlocutors and audience are important, but only in the sense that respect, non-mean-spiritedness, and sensitivity to the ways thinking and truth are hard are valued. That a particular idea or view may cause discomfort or pain isn’t in itself a reason to exclude or cancel or silence it, as long as it is not meant to harm, is contemplated openly with a hope for understanding and truth, and is honestly and respectfully discussed using reasons and evidence. If this wasn’t an ideal we would never tell our children the truth about the tooth fairy or santa claus, and philosophers would never contemplate nihilism or radical evil for example.

In reply to David Wallace,

I think you are mistaken about the novel. A central feature of Big Brother’s regime is Newspeak, whose purpose is to make thought crime literally impossible by subsuming both social conversation and every individual’s epistemic faculties under party control– not merely behavioral outcomes, but what it is possible to know. A central premise of the book is that regular violence must be extended– socially and linguistically– into individual psychology for a totalitarian regime to really, truly become total.

So, I’d argue that using Newspeak was probably “the typical oppressive speech act” in the novel. Of course, the epistemic coercion depends to some extent on being backed by regular violence. But I don’t think it rests solely on regular violence. See Mill’s arguments about social/epistemic tyranny.

On a side note, maybe ‘epistemic coercion’ would be a better term. Epistemic violence is a bit too metaphorical. However, I think this metaphor gets more currency than we realize (especially when talking about oppressive speech), which is why I brought it up.

To Matthew Capps: I don’t think it’s even faintly possible to make sense of the world of 1984, including Newspeak and attitudes towards it, without the omnipresent literal violence and threat of literal violence. And hardly any of the novel’s dialog is actually in Newspeak – it’s talked about but rarely used. But this thread’s probably not the right place for literary analysis – especially of a novel I haven’t read for twenty years – so I won’t push the point further.

This post at BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY addresses the constraints on freedom of speech in the contexts of Canadian philosophy and Canadian philosophy departments :https://biopoliticalphilosophy.com/2020/12/15/opposition-to-bill-c-7-and-too-many-letters-of-reference/