We Still Have Work To Do

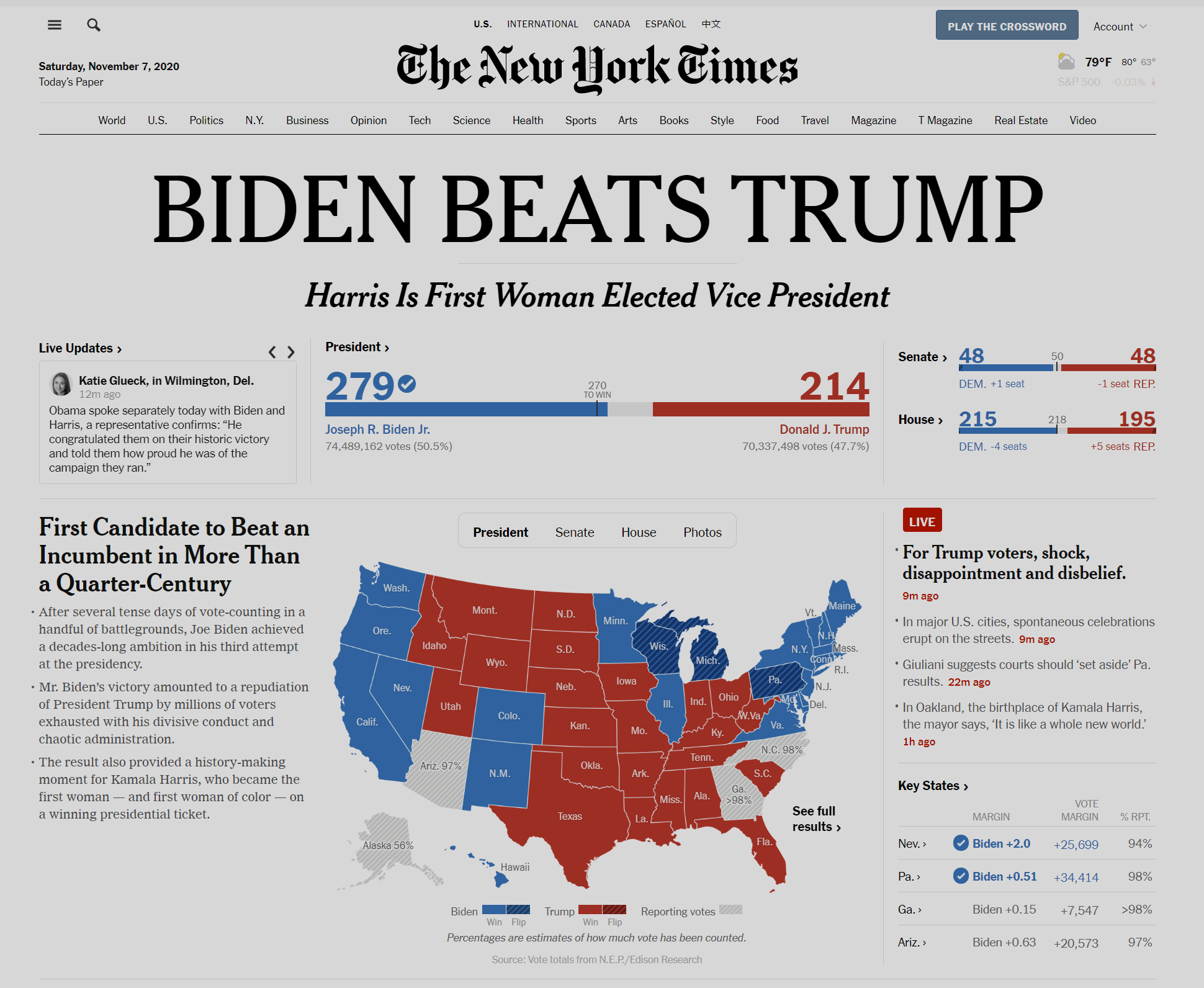

Joseph Biden has defeated Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election.

Thank you, fellow 75 million Americans who voted for Biden and Kamala Harris. Trump is [negative adjectives of your choice] and we are very fortunate to be removing him from the presidency. I shudder at what the country might have looked like with another four years of him at the helm—as it is we have much to repair and recover from.

Trump’s defeat is worth celebrating, and I hope you all* get to do a little bit of that this weekend.

Four years ago, when Trump won, I asked: “What should we do? By “we” here, I mean we in our capacity as members of the community of professional philosophers.”

This question remains a live one, and for many of the same reasons. Trump will not vanish from the political landscape, and neither will his followers. Over 70 million Americans voted for him—more than in 2016—and presumably many of these people did so because they like him or think he has been doing a good job, and not simply because they don’t like Biden or Harris or the Democratic Party.

In response to that question, I identified three elements of what came to be called “Trumpism” that I thought philosophers were particularly well-suited to address. They are still on the list:

1. Lack of respect for expertise. One glaring hallmark of Trump’s campaign is his apparent lack of respect for expertise, and the concomitant belief that the relevant questions are simple and their answers easy. The confidence with which he expressed his detail-less assurances that he could offer “tremendous” solutions to problems it was quite clear he did not understand ought to have been a bright warning sign. Philosophers are in the business of showing how the apparently simple is really quite complicated, once you think about it. This point is applicable across nearly every domain, especially governance and the various political, economic, and social challenges that governments address.

2. Inattention to sense. Is it that people don’t know when what they’re hearing doesn’t make sense? Or do they not care? Or do various cognitive biases interfere with people’s understanding of what makes sense? Yes, yes, and yes. Philosophers have long placed careful reasoning among their pedagogical goals. We need to do a better job of that, though. And we need to take up the task of motivating rationality. We academics—philosophers, especially—don’t generally need to be motivated to try to think rationally, but we are not normal. Additionally, we need to incorporate into our courses findings on the biases that interfere with proper reasoning, along with debiasing strategies.

3. Focus on the visible, rather than the important. Part of Trump’s success was owed to his ability to paint challenges as conflicts, and then foster solidarity with potential voters against their “enemies.” Yet the construal of these conflicts works by drawing attention to superficial and ultimately unimportant differences, and ignoring underlying and more important similarities. Insofar as philosophers teach others to look below the surface, and to not take things simply as they appear, they have a role to play in undermining some divisive appeals. Merely drawing attention to the pervasive role of chance or luck in everyone’s life can get students to be more thoughtful about the kinds of problems governments tend to address.

The intervening years have made clear that many other things need to be on such a list. I’ll mention one more,:

4. Constricted imagination. Much of the cruelty (racism, xenophobia, etc.,) Trump exemplified and encouraged seemed to be facilitated by a lack of thought about the question of what is it like to be (or be in the position of) the people who were the targets of that cruelty. Learning more about what the lives of others different from you are like, learning how to take those perspectives seriously, and learning about the epistemic hurdles we face in doing these things are undertakings philosophers and other academics can help with, with the goal that disputes involve more understanding and less dismissiveness.

I leave it to commenters to add other items to the list.

To be clear, the idea is not that better philosophical education will eliminate political disagreement. It won’t, and we shouldn’t want it to, anyway. Rather, the hope is that it will improve political disagreement, and get people to be more thoughtful. We have our classrooms, we have more opportunities for public-facing work and outreach than ever before, and now we have one less obstacle. Let’s get back to it.

But let’s raise a glass first.

* Yes I know some readers of this post will have voted for Trump. Perhaps they can be happy to be rid of a certain degree of non-partisan problems Trump exemplified.

P.S. Look for a “Philosophers On” post about the election this coming week. Here’e the one from 2016.

I am genuinely surprised that someone who predicted a Biden landslide, feels “particularly well-suited to address” the problem of Trumpism. I believe that your miscalculation demonstrates that you do not understand the political realities around you very well. I also believe that this self-critical insight should be the starting point of your call for political engagement. As philosophers we have to learn from the experts (the political activists, the community organizers etc.) how we can develop political sense and have political impact. Things look different from the armchair than they are on the street. Your third proposal is a case in point. I believe that Trump’s divisiveness has revealed real conflicts that are often hidden from our eyes. We have such privileged positions as academic professors that we can dissolve most conflicts in verbal disagreements. Our bi-weekly checks will come not matter what the outcome of the dispute. Finally and most importantly, we should thank the grass roots organizers in Detroit, Atlanta, Philadelphia etc. who have turned things around. And we should invite them to get their thoughts on what is needed right now, also from us. Trumpism has defied the laws of an alleged political normalcy a second time (more votes than 2016 despite everything, QAnon is in the House now, Republicans can still win the Senate majority…). That you did not see it coming the SECOND time, should make you a little more humble…

The four elements of Trumpism that I mention in the post were ones that seemed to me to be both problematic and something that could in part be addressed by philosophers in their professional capacities.

This post was not intended as a strategy statement for how Democrats can win elections, and I don’t see how my slightly-off political prognostications have any bearing on its substance. Further, the post was not intended as an exhaustive list of all things wrong with Trumpism, or of all things that can be learned from Trump’s popularity, or of all that we should do about Trumpism. Suggestions were explicitly welcomed.

That said, your point about Trump’s divisiveness revealing real conflicts is an interesting one and if you want to make suggestions about how philosophers might take that point to heart in their work be my guest.

What should we say counts as ‘winning big’ right now? If it turns out that Biden eventually gets 306 EC votes to Trump’s 232, and maybe 5 million more individual votes, should we count it as a big victory in today’s US political climate? Can’t see it making sense to compare it to anything more than 20 years ago. But on EC alone, it would larger than both of Bush’s wins, identical to Trump’s 2016 win, and smaller than either of Obama’s wins, so it’s average in that sense. On popular vote, Biden’s percent advantage is one of the largest (second only to Obama’s first win?).

Relatedly, people might have been right in forecasting a (big?) win for Biden, but wrong about when its scope would become noticeable. Recall the 2018 midterms, where the night of and day after the forecasted ‘blue wave’ didn’t seem apparent, to the dismay of some Democrats. But within a week or so the true scope of the victory came into focus, and now those midterms are rightly counted as one of the biggest swings in recent history.

With that in mind, and regarding ‘what to say’ about Biden’s win, and what sort of mandate that implies, one thing I want to caution against is the idea that this somehow speaks in favor of a moderate or centrist approach. For many months progressives were told (or scolded) to just plug their noses and vote for Biden. So it would be very strange indeed to now read Biden’s big(ish) win as somehow indicated a decisive vindication of his centrism. Alas, that seems to be the line that many Democratic party leaders are taking right now.

When did (so-called) philosophers decide that the people with whom they disagree are unintelligent, racist, fascist, and all other sorts of evil and incompetent?

I ask because that seems to me like a very unintelligent way of “engaging” (clearly there is no genuine engagement going on) and an impoverished representation of or claim to “doing philosophy.”

“How do we fix the baddies/get those rubes to be more thoughtful?” is an obtuse reaction to recent events. Genuine reflection would maybe focus more on ‘us’, for example: what is so alienating about the left that it would drive people into the arms of such a destructive person/movement?

The problems of Trumpism I discuss in the post seem to me apt characterizations based on what we’ve seen over the past several years. It’s an incomplete list focused on the kind of problems philosophers tend to be in a position to address in their work as teachers and creators of public philosophy. I don’t see why we should not, on a website dedicated to discussing matters related to the philosophy profession, take up this topic. If you think any of them are really off base, let’s hear it, but I don’t see why you’d dismiss the inquiry.

That there are other questions to be asked about the election is certainly true. But it’s not clear to me that “electoral strategies for the left” is something we’re particularly well-placed to take up here, and that is not what this post is about.

Exit Polling Data:

Among those who never attended college at all, Trump beats Biden by 3%.

Among those with no college degree (including people with no college and people with some college), Biden and Trump tied.

Among those with a college degree (but no graduate degree), Biden beat Trump by 13%.

Among those with advanced degrees after a bachelor’s degree, Biden beat Trump by 26%.

Source: ABC News – https://abcnews.go.com/Elections/exit-polls-2020-us-presidential-election-results-analysis

In response to “Data”. While some may be tempted to explain these figures as showing that people who voted for Biden over Trump are more educated, and therefore better able to pick the overall best candidate, we should consider the alternative explanation — which is that college educated Biden supporters are just voting according to their own class interests. This review of two books critical of meritocracy indicates why we should consider the latter:

https://www.newstatesman.com/david-goodhart-head-hand-heart-michael-sandel-tyranny-merit-review

In response to Chirimuuta:

More voters who made over 100K a year shifted to Trump and more who make under 50K shifted to Biden compared to 2016 (and Biden also got more votes in absolute numbers from voters who make under 50K).

So: would you also agree that perhaps “class Interests” explains this vote?

This is in reply to Justin above (the reply button doesn’t appear to be working for me). Thank you for your response.

In the original post, you say you want to “get people to be more thoughtful”—the people in question seem to be Trump voters, and we philosophers can help with their intellectual deficiencies and thoughtlessness. This is precisely the kind of condescension that many on the right find alienating. So it’s bad in terms of a political strategy, but also, are they not right to feel affronted by this kind of thing? It’s just bad philosophical procedure here, to assume that all the reasons I find Trump atrocious are also the reasons others find him attractive. “Let’s get to work telling these people how to think!” is self-righteous and unreflective, particularly coming as it does from people who seem to have no conception at all of the values and thought processes of a typical Trump voter.

Hi Prof L. You present three objections to what I wrote:

1. It is condescending in a way many on the right find alienating and so is a bad political strategy.

2. It is offensive to many on the right, regardless of its effectiveness as a political strategy.

3. It’s “bad philosophical procedure… to assume that all the reasons I find Trump atrocious are also the reasons others find him attractive.”

In response:

1. I’m not offering political strategy.

2. I’m having a conversation with my colleagues. It’s true that some people might be offended by the content of this conversation. Such is life. I don’t think the possibility that some people might be offended by this frankly tame discussion is a particularly strong reason not to have it.

3. I’m not assuming this. I saw a fair amount of the problems I identified in the post exemplified by Trump and his supporters. Whether this was owed to them being happy about them and not seeing them as problems, or just not finding them too objectionable, I don’t pretend to know.

Now I’d just like to point out that this always happens. Rather than take up the substantive points, which here would be (for example) identifying other problems, or arguing that the problems I identified were not in fact present or are not in fact problems, my critics from the right too often instead launch peripheral complaints, either about form or tone or inclusion or whatever. This is frustrating, to say the least.

(And yes, for some reason, the “reply” button appears to be broken for visitors to the site. I’m sorry about that, and hope to have it functioning again soon.)

In response to Data. (Again, ‘Reply’ button not working). All of these data need more fine grained demographics before one could say anything very substantive. But, yes, plausibly class interests might explain Trump’s rising vote share amongst very high earners — his only big legislative win was some tax cuts for the super-rich!

That’s completely consistent with the above point that the Democrats serve the class interests of a large sector of the college-educated. Goes without saying that the Republicans serve the class interests of the ultra-wealthy! (The concern being that neither party serves the class interests of low income voters without degrees.) Again, there’s only so much speculation one should do without more fine grained data, e.g. race, and income brackets above 100K. I don’t actually want to get into those finer points. My initial post was just to say that any idea that education correlates with better informed voting choices, comforting as it may be for people like me who work in university education and who wanted Biden to win, can be pitted against explanations in terms of class interests.

Hi Justin—I’m sorry you find this frustrating, and since this is not in line with the discussion you would prefer to host, I will stop commenting after this. Thanks for hosting these discussions and putting your views out there—disputing about contentious issues is one important way to progress toward truth.

Just a note: I’m not ‘from the right’, unless you just mean to the right of you: perhaps, on some issues. I assume many of your other “critics” here also would call themselves liberal or progressive.

wrt your #2, I do not think that the likelihood of causing offense is a definitive reason to desist from discussion. You aren’t offering political strategy, but you said you want to ‘”get people to be more thoughtful”. The starting point of “here’s what’s wrong with *them*”—without any good-faith investigation of reasons someone might have for voting for Trump—is a sure-fire way to make whatever comes out of this discussion completely ineffective for that end.

And wrt #3, fair point. The Trump voters I know voted for him in spite of many of these things, and their disgust for an out-of-touch left overcame their disgust for Trump. Some held their noses to vote, others gradually became gleeful at Trump’s ability to troll the left, and adopted the values you mention. Maybe Trump will stick around, here’s hoping he doesn’t. I tend to think he won’t have a huge influence on the mainstream going forward, and the idiosyncrasies of ‘Trumpism’ will go away. But the animosity that gave rise to it will stick around, fueled in part by condescension like that on display in this post, and its own peculiar thoughtlessness.

On point 1, the distrust of experts seems to me be as much a distrust of theory. I suspect they have a kind of respect for practical expertise, or for expertise born of skin in the game, but are deeply suspect of people who operate in the realm of pure theory or and research. This is probably connected to the fact that they think a lot of experts who are highly influential (ie. policy makers, economists, pollsters….) do not have anything at stake in the decisions that are actually made using their expertise. This probably helps makes sense to the hostility they express towards experts. (to be clear I love enjoy theory for theory’s sake, and all manner of speculation)

I too am grateful for this discussion, but I also want to ask an honest question to Justin (as someone who is also relieved about the outcome): you don’t think what you said in your initial post is condescending toward the +70 million people who voted for Trump? Many of them are close friends, mentors, and colleagues that I disagree with, but who are intelligent people of good will. I wanted to make sure I understood you correctly because you did also sound to me as quite condescending toward them. It seemed like you thought they were either ignorant or morally bad. Is that not right? Feel free to correct.

*head explodes*

Justin, re: “Learning more about what the lives of others different from you are like,” well I can’t think of anything more pedagogically important than that! But since most of us are liberal white academics, I suppose that means we have to encourage one another to learn what it is like to be, for example, a working-class Latino Trump voter, right? This isn’t just some political “gotcha” point, the philosophical literature on this is clear: empathetic projection requires understanding the reasons that our targets are operating under. In other words, accusations of bias and cognitive deficiency are the enemies of empathetic understanding, because bias doesn’t *feel* like bias, it feels like acting and believing for good reasons. So don’t you think this post kind of enacts a strange performative contradiction here? Declaring that what Trump said doesn’t “make sense” is to automatically preclude empathetic understanding with Trump voters, because it clearly made sense *to them*, right?

“Head Explodes” seems puerile. I wish if you would answer without condescension. But that’s okay.

As to respect for expertise, I think Trump and Trumpism are not equivalent here. Trump himself does seem vastly overconfident in his own abilities to solve problems way beyond him. At least, that’s part of his schtick. And his administration did try to meddle unconscionably with, e.g., the CDC and FDA during the pandemic.

But it’s not just about Trump: the Republican electorate in general is pretty skeptical of expertise as it impacts political questions. I presume the readership here is pretty familiar with that! There is another side to that coin want to point out here. This isn’t about moral equivalence, just a factor worth noting: the desire of liberals and progressives to reduce political/ethical questions to questions of technical expertise, and the tendency to anoint ‘apolitical’ saviors of the nation. An example of the former: considering lockdown skepticism to be “anti-science,” and the related pretense that there is professional consensus on massive, unprecedented NPI’s for a novel pathogen. There is, more broadly, the cultural apotheosis of “science” as both a monolith and an oracle, but above all a badge of team identification: “I fucking love science”, “In this house we believe science is real,” “follow the science.”

Some recent examples of the latter: James Comey, Robert Mueller, the pop star-ification of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Anthony Fauci. If you want to cringe, go back now and read all the hagiography of Comey and Mueller as the saviors of our polity. In both cases they instantly fell from favor once their ‘apolitical’ actions had an unfavorable political impact. Even more cynically, there’s the reinvention of various FBI/CIA/foreign policy creeps as talking heads who supposedly speak for some previously untainted noble profession of public service – Clapper, Brennan, etc. Gross. Fauci deserves his credibility, imo, but it does him no good to try to make him a political hero (Shephard Fairey postersand then complain that he is regarded as a political figure.

Politicians, being responsibiilty-averse, want such figures’ apolitical (or, in the law enforcement and foreign policy cases, supposedly apolitical) expertise and professional cred to suffice to answer essentially political questions – that’s much nicer than having to own a political decision. Not surprisingly, that often doesn’t go well – it’s just another way of politicizing the discipline or profession that desired savior comes from.

I agree with Led that the left often tries to use science to dodge the moral debate around policy choices. (Libertarians also do this, especially with the supposed results of economics). Consider lockdowns. I strongly support them myself, but in putting them in place there will be trade offs: Children and college students won’t get as good an education and service workers will suffer. Both of these losses will disproportionately affect the less well off since they’re the ones who lack reliable internet access to access online education and tend to work the jobs most vulnerable to lockdowns. In fact, these are the reasons that de Blasio was initially so resistant to lockdowns and why Sweden’s social democratic government has remained so. As Nate Silver and others have noted it’s easy to imagine a possible world where say President Kasich or Jeb Bush is imposing lockdowns and resistance to them has become a left wing issue. As I said I tend to support lockdowns and I personally think the way many anti-lockdown arguments discount the lives of the sick and old is disgusting, but it’s just dishonest to say that pure science settles this. There is a legitimate moral debate to be had and we’d do well to acknowledge that and not just try to shut people up by invoking science in the way my more ignorant Sunday school teachers would invoke the bible.

We should also admit that experts sometimes are fantastically wrong about things and that the lived experience of many Trump voters gives them reason to be especially skeptical of experts. Consider the free trade consensus. It’s become clear that the claims that free trade leaves everyone better off are just fairytales. One need only drive through my own state of Virginia west on Rt. 58 to see that that’s nonsense. Clinton’s free trade deals absolutely devastated the manufacturing industry in southwest and southside VA and most places there have never recovered. And yet I clearly remember 20 years ago when the experts told us that these deals would be good for those areas and that resistance was driven only by ignorance. I’m betting many people in places like Martinsville, Hillsville, or Galax, do too (they’re not as ignorant as you like to pretend). Or consider the Iraq War. Here expert opinion was more divided but there was a huge slice of self-proclaimed foreign policy experts, including Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton, who supported the war and told the public that the aftermath would just be awesome for everyone involved. Again people haven’t forgotten that and unlike relatively well off, liberal academics working class people in places like Hillsville, Galax, or Wise are likely to have family members or close friends who served in the military and so suffered pretty directly from the arrogance and incompetence of “experts” like Clinton and Biden. I’m going to guess that many black and hispanic voters also lack the “proper” reverence for experts for similar reasons and I wonder if that isn’t part of the reason Trump did shockingly well in those groups.

This country was founded on a healthy kind (and not so healthy kinds) of elitism. This is why we buffer between the masses and power. Elites must, however, balance this elitism with a healthy amount of self-reflection and empathy for those with whom we disagree. I think we strike the balance too far toward the latter when we worry about the inevitable “condescension” that results from a reasonable evaluation of our national situation.

I think both of these propositions can be, and are, true at the same time: (1) the left is out of touch with what really motivates the Trump base, and therefore more self-awareness and humility is needed; and (2) being honest about the problem on the right not only justifies but requires conclusions that will invariably be interpreted as condescending and insolent in the eyes of the Trump supporters to whom the criticism applies (I don’t think that generally fair criticism of the Trump phenomenon applies to all Trump supporters, but only a critical mass of them).

As for strategy, it doesn’t really matter how condescending anti-Trumpers are; the base of the right will still demonize and hate the left for some reason. There are media outlets that exist for the sole purpose of catering to some folks’ need to have a consistent enemy.

The area where philosophers on the left can have the most impact is not on the right, but on the left. Yes, the problems on the right are much, much greater—e.g., the escalating epistemic rot from climate change denial, to Trump, to QAnon. We should do what we can regarding that, but it seems that what we can accomplish there is pretty minor compared to the impact we could have on mitigating those epistemic vices on our own side that, while smaller, nonetheless, both add fuel to the fire of hyper-polarization and lead us down counterproductive paths–e.g., see Clyburn on “defund the police” (which is intentionally ambiguous between reformist policy and police abolition) and its costing Democrats seats in the Senate and House. It is insane that the left adopted and/or long acquiesced to this slogan, but not surprising given how little pushback it received (because of how anything even resembling pushback is received—e.g., David Shor). The appreciation of debate and nuance, which are crucial for self-correction, is way too low on the left right now, and mitigating this is an area to which philosophers could significantly contribute. It may seem unfair to aim criticism leftward while the right is more deserving, but that presupposes that criticism is a hinderance, as opposed to a crucial asset.

Thank you for your reply, Justin, and the offer to contribute. I hesitate, since I do not see myself in the position to tell others what to do. Here are some ideas nevertheless:

1. Reflect how your social position influences your moral intuitions, your selection of research topics, and the way you work on them. There is plenty of social psychological research that demonstrates how the social position and the social origin of people influence their moral and epistemic preferences. I do not believe that philosophers are an exemption.

2. Connect with the people who engage with ordinary political life on a daily basis. I believe that we can learn from them how political beliefs are formed, how political conversion can happen, and what the real issues of ordinary people are that motivate them to take sides.

3. Stop mystifying academic philosophy. We are an overly narrow discipline in many respects. Here are some examples: We are predominantly white, male, and middle/upper class. We have an extremely narrow white and male canon. Many analytic philosophers believe that continental philosophy is not philosophy proper and the other way round. Many systematic philosophers disregard historically orientated work as making no real contribution to philosophy. And these are not only personal preferences. These preferences are mechanism of exclusion that shape our publishing contexts, hiring decisions etc. Put briefly, we are the ones who have to learn “constricted imagination”. We are far away from being in the position to teach it to anybody. Put more constructively, help to widen the scope of what counts as philosophy.

All three points are instances of learning: learning about yourself, your political context, and your peers.

Wasn’t Trump the first president in more than 40 years who did not start a new war? The rest of the world appreciates that.

I interpreted the question this way:

A large number of Americans voted for a man who is willing to flagrantly lie and undermine our democracy in order to achieve power. What explains this? What should we do about it?

These seem to me to be very reasonable questions that Americans of all political persuasions should want answers to.