Students Have Easy Access to Ghostwriters for Hire — What Should Teachers Do?

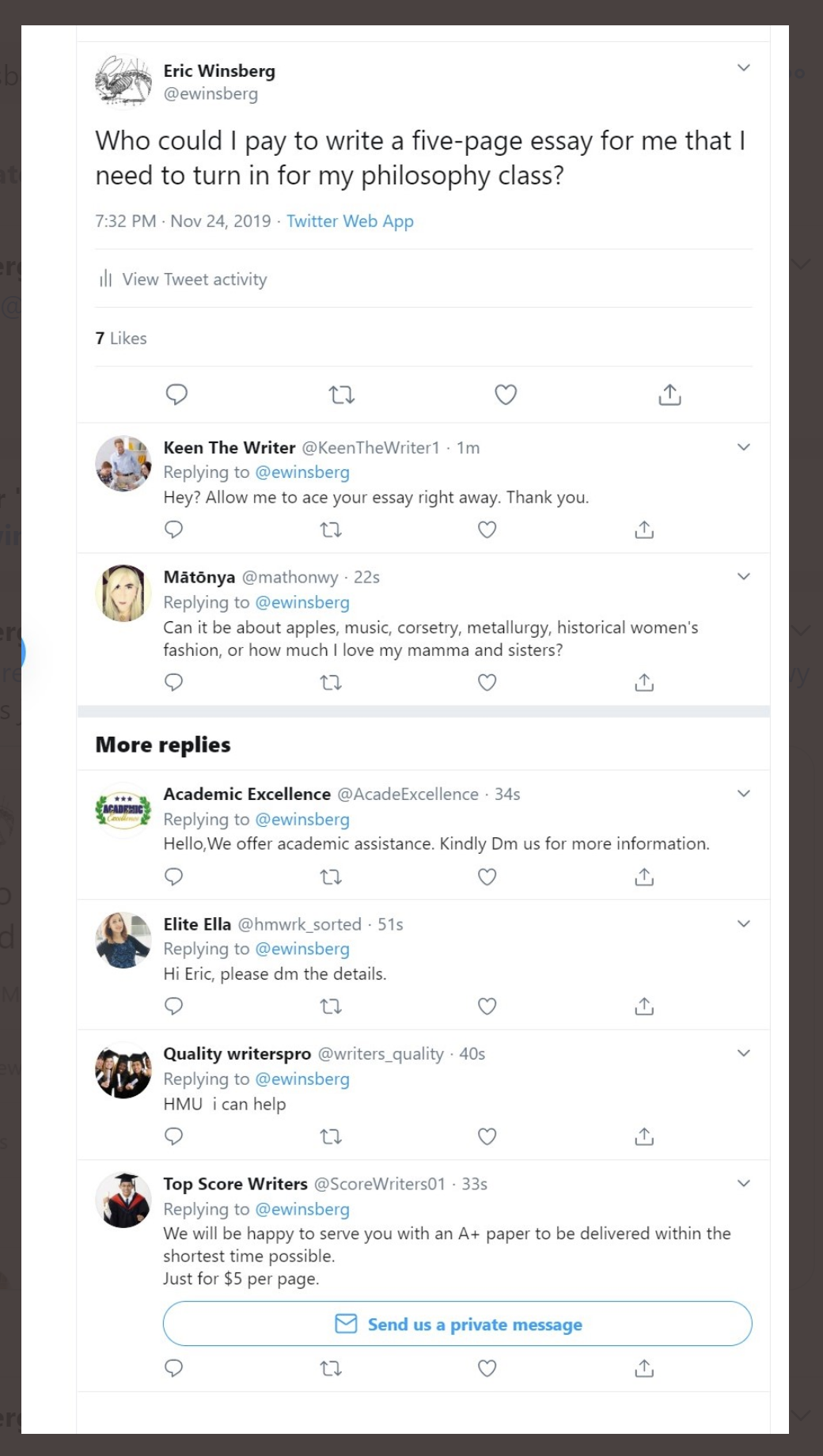

Recently, Eric Winsberg (South Florida), as an experiment, tweeted, “Who could I pay to write a five-page essay for me that I need to turn in for my philosophy class?”

As the semester comes to an end and assignments pile up, some students may be tempted to cheat by hiring others to write their papers for them. Professor Winsberg (@ewinsberg) found out you no longer need to approach these ghost-writing services or visit their sites. They’ll come to you—quickly, and in droves.

A sample:

This is not exactly news. Winsberg himself joked at his naivete in being surprised by the responses to his tweet. “I was aware there were paper mills,” he said in response to someone who linked to a news report on Kenyan ghostwriters who do some of that work, adding “I wasn’t aware that all you had to do was tweet and 20 would pop up.”

According to a New York Times article on the use and production of ghost-written papers, it is not clear how many students purchase them. It reports that 7% of undergraduates admitted to submitting papers written by someone else, but that statistic is from 14 years ago, an eon and a half in Internet years. There are worries that it is now “a huge problem.”

The use of ghost-written essays is difficult to detect. Plagiarism detection software will not catch it unless the ghost-writer uses plagiarized material, and, as David Tomar, who says he worked as a ghost-writer for essay mills for years, says:

Though the optimistic educator may take some comfort in the view that paper mills are not legitimate enough to constitute a threat, there are rules for professional paper writers and the more successful companies will enforce them. Chief among these rules is the responsibility to provide completely original, never-before-used material crafted to respond to a specific assignment inquiry. This product is the cornerstone of this industry’s success.

So what to do? Here are some pieces of advice from Tomar for making it more difficult to use ghost-written work:

1. Teach up-to-date, carefully-constructed courses that make use of distinctive content and assignments:

A generic assignment begets a generic essay. If this is all an instructor seeks from his or her students, said instructor makes it nearly impossible to differentiate between the work of a pupil and the work of a person who has never set a foot in the lecture hall. If, by contrast, one designs materials, assignments and exams with thought, care, and specificity, one has much better odds of spotting the work of an outsider.

2. Give in-class writing assignments:

Partial emphasis on in-class writing exercises, when supplemented by out-of-class assignments, is a powerful way of getting to know students’ writing capabilities and voices. Class time should be used to challenge students with unique and fun writing exercises… No matter how convincingly a ghostwriter writes on a given subject, this approach provides a document whose authorship is not in question as a point of comparison.

3. Assign multiple drafts:

Using the multi-draft process can stretch an assignment out across weeks or months. This results in a greater length of exposure for the cheating student. Instead of the once-and-done security of getting away with a single ghostwritten assignment, each student knows that his or her work will be held up to sustained and ongoing scrutiny. By inserting one-on-one conferences into this draft process, the instructor can heighten this scrutiny by requiring each student to defend the approach, argument, and decisions comprising the written work.

4. Personalize the subject matter:

Assignments that incorporate personal experiences and interests not only offer students a welcome reprieve from the rote, repetitive, or regurgitation-based work that makes up so many courses, they also make it more difficult for the ghostwriter to assume a student’s identity. This challenge may even strain the credibility of submitted assignments to the point of making them more detectable… Knowing one’s students on a personal level might, in this case, provide more than enough information to peg suspicious assignments.

5. Emphasize class discussion in writing assignments:

Assignments that rely strictly on standard texts make the ghostwriter’s job very easy. Most texts are readily available online. By contrast, a lecture, a class discussion and the experience of being a part of both should be something unique and impossible to replicate.

6. Give assignment “exit interviews”:

Standardizing one-on-one conferencing with each student following assignment-submission requires each student to defend his or her writing. This is an especially attractive approach because it need not revolve around the suspicion of cheating. This healthy exercise can simply serve as a way of helping the student to reflect on the content of an assignment and the process involved in its completion.

Tomar gives much more advice here, including tips on detecting ghost-written assignments but also on getting students to be sufficiently engaged in the course that they are less motivated to outsource their assignments.

Feel free to share your experiences, advice, and ideas.

“The WriteCheck service, provided by Turnitin, is designed to allow students to run an article through its software to check for plagiarism for a one-off fee. Our evidence suggests that essay mills also say they are accessing the service in order to reassure potential customers. ”

https://www.researchresearch.com/news/article/?articleId=1383297

Don’t many universities subscribe to stuff too, like SafeAssign, that check this? (That one checks the percentage of content that could have been cut/paste from the internet, though that would include many legitimate quotations.)

Maybe the point is that “good” ghost writers can just write from scratch, so this doesn’t help. There’s a bunch of good suggestions above, but I’ve just tried to make prompts that can’t get hacked. Students can still get friends to write, I suppose, which is maybe one reason the exit interview is neat–though probably too labor-intensive to get off the ground. Ditto on multiple drafts, though I know some people that do that.

Right, all these people at least promise that their essays contain no plagiarism. (That is, until the student puts their own name on it and turns it in.)

Dan Ariely ran an expert ok this a few years back. The results are quite encouraging.

http://danariely.com/2012/07/17/plagiarism-and-essay-mills/

But that was back in 2012! As I understand it, the essay mills are improving rapidly.

I’m not sure this is worth worrying about. If folks are going to cheat on an intro or ethics paper, they’re going to cheat. Unless you want to make them write in front of you, there’s really no way to prevent this. Might as well spend the time worrying about how to get the students who care to get more out of the course.

Sure, they’re going to cheat. But they can be forced to overcome obstacles that make it difficult to get a good grade when doing it. My assignments make reference to lecture and discussions specific to the way I teach the material. This makes it difficult for people turning in ghost-written papers to get a C or better on the assignments because the papers have to include information specific to class meetings to write an adequate paper. Creating assignments like this is easy enough for some of us that we’ll have plenty of time to work on ensuring the students who care get a lot out of the course.

I don’t understand what the suggestion is here. Is it that we should just permit cheating, because people will cheat? More generally, is the idea that if people try to do something bad, and we can’t prevent them from trying, we shouldn’t bother doing anything to stop them from succeeding at it?

If so, that sounds very implausible to me. The main reason we are able to do this job is that people pay us to confer a credential on them (without that credential, almost all those people would try to learn without paying tuition fees, if they would bother to learn what we teach at all). And that credential has value only if others have good reason to believe that it can’t easily have been acquired dishonestly. If enough of us have policies of letting cheaters have whatever credentials they want, then there goes the profession.

Nearly all the sincere and hard-working students, also, seem at least partly motivated by a desire to earn a high grade. If they discover that their instructor regularly gives high grades to cheats who put in no work, and just shrugs at that practice, why will they continue to work as hard? And why won’t they feel resentment at being given the same grade, or a worse grade, as someone who just bought his or her A paper?

Also, how is this fair to honest students who don’t have the money to buy their As?

I don’t think the suggestion is that we should permit cheating. I think it’s that we should prioritize our job as educators over our interests as peddlers in credentials. I guess I’m old fashioned, but I think the students who actually do the work are learning something, and that that education is its own reward. When I catch cheaters I punish them, but I don’t design my class around the assumption that students aren’t cheaters, and if I’m going to put extra work into my teaching, it’s going to be directed at helping students learn, not catching the more sophisticated cheaters.

You’re right of course: If our primary job is selling credentials, then we should spend most of our efforts policing the value of that credential. But if our job is also to be philosophers and educators – not mere sophists – then we have to choose how to prioritize those very different parts of our jobs. If there are things that serve both simultaneously – e.g. requiring/incentivizing/inspiring class participation; having assignments that come in multiple drafts to allow development as a student/writer; – great. But I didn’t accept the opportunity costs entailed by a (still precarious) academic career to focus my professional energies finding ways to catch cheaters.

Should have been “I don’t design my class around the assumption that students ARE cheaters.”

Correct.

_One_ of the factors here is our interest in our position as trusted adjudicators (not at all the same as ‘peddlers in credentials’ — the mere peddling of empty credentials is what we will become if we carelessly allow cheating to go unpunished, and spread even further than it does already, so that people can literally buy their way to the credentials we bestow). If we can no longer provide students with trustworthy credentials, the bottom falls out of the profession, and that’s bad for all of us.

But yes, let’s put aside the interests of the profession and consider the students’ interests:

1) Does it help, or harm, the students if we continue to give out unearned credentials to cheats, and do nothing to stop them? Clearly, it harms them. The credentials we thus bestow signify less and less, and thereby become less and less trusted by the people they wish to impress by those credentials. Already, this is becoming a crisis. In a recent survey of over 70,000 undergraduates, over 60% of them(!) admitted to sometimes cheating on written exams (https://academicintegrity.org/statistics/). This is the equivalent of the mint allowing the unchecked printing of counterfeit currency. It doesn’t make everyone richer. It just makes the money of honest people depreciate.

2) We can also go further and put aside the question of credentials completely, focusing only on how effectively we teach the students in our courses if we decide we don’t care about cheating. The good teachers among us challenge our students to meet difficult goals. This requires them to put in a good deal of work, but that work should pay off. The achievement of a high grade on an assignment or exam is a sign that their work has paid off, and a source of gratification to them. If students get a B on a difficult assignment after devoting fifteen hours to it, and then get laughed at by the student sitting beside them who just bought the essay in five minutes and got an A, it demoralizes them and makes them feel that it wasn’t worth the bother. How do I know this? Because many students have told me what it feels like. It’s also not hard to imagine. If you were in some competition — for leisure, or for a job, or for getting your article into some impressive publication — and found out that many of the successful people around you got their by just straight-up cheating, would you really work as hard at it? Would you really take the whole process as seriously? Few people do.

Chris,

I more or less agree with you. But that’s why I found this alarming even though I already knew there were outfits like this. I figured they were only being used by the most nefarious students. But it appears that these outfits aren’t only offering the service to students who seek them out, they are actively luring students into it. something something about keeping honest people honest something something. I dunno…

Or just don’t assign “papers”. Have them do something else. Give them objective format tests. Make them do worksheets in class. There are ten thousand alternatives to the essay model. (And, while I’m happy to be corrected, I’ve never seen a shred of evidence that writing essays shows that the students studied, or learned – or whatever it is you want to measure.)

What writing papers can demonstrate is an ability to think critically, to analyze or solve philosophical problems, to acquire a deeper understanding of those problems, to analyze an argument, to construct valid arguments, to invent ingenious counterexamples, and so on. Scientific evidence supporting this would not be very interesting since experience in grading papers is enough to support it. I don’t know why anyone would care to wait for scientific evidence of this before acknowledging it. Of course, these abilities can be demonstrated in other ways. But paper assignments are just fine for this, and writing papers can help prepare them for writing Honors theses or writing samples, among other things. This is reason enough to assign papers.

Well, I require empirical (that is, scientific) evidence for empirical claims. If you don’t have evidence to back up your claims, I can’t understand why you think they’re true.

There is a dog in your home. This is an empirical claim. Do you require scientific evidence before you accept or deny it? Turning the door knob allows you to open the door to your home. This is an empirical claim. I assume you think it’s true, and don’t require scientific evidence to support it. So, I assume, you’ll agree with me that it makes sense to believe some claims even when there’s no scientific evidence to support them.

I’ll say all those count as scientific. And I’ll also say you’re avoiding the issue. As for your claims about paper-writing, you could try to back them up with some evidence, rather than just assert that you “know” that they are true, when, in fact, you don’t. You could try various experiments, try independent ways of measuring student accomplishments. When I do things in the classroom, I want to know whether or not they are effective means to my ends.

I’m not avoiding the issue. The issue is whether the claim that writing papers can demonstrate an ability to construct valid arguments, to analyze arguments, understand philosophical arguments (etc.), is a claim of the sort that it makes sense to believe without scientific evidence. I’ve been suggesting that it is. It’s not that it doesn’t require evidence at all; it’s that it requires evidence that we get through experience in grading papers. When a paper has an original valid argument in it, it demonstrates an ability to construct a valid argument.

Empirical evidence and scientific evidence are just not the same thing. One could empirically observe a one-off supernatural event. We wouldn’t say that there was scientific evidence of the supernatural if that happened, would we? People have had empirical evidence for their beliefs in prehistoric times, but science was invented more recently. You yourself suggest that scientific evidence involves experiments. Anyhow, if you want to just use ‘scientific evidence’ and ’empirical evidence’ interchangeably, go for it. But then there’s all sorts of empirical/scientific evidence that writing papers demonstrates certain philosophical abilities: e.g., I’ve observed that people with better philosophical abilities (as determined by personal interactions and performance on other assignments including exams) tend to do better on papers.

Sure, fine. All I’m asking for is better evidence than what was presented, since, in fact, no evidence was presented at all. And it’s not hard, it’s really not hard, to provide that evidence, to run experiments on our pedagogical practices, to record observations. In fact, it’s so easy it’s remarkable that nobody here seems to think it’s important.

Also, writing itself is (still!) and important skill, and many students don’t get enough of it. Like many skills, practice is an important part of learning it, so there’s value in assigning writing for that reason alone. Many of the skills needed for good writing are also found in presenting ideas clearly and logically in other areas, so there are additional benefits, too. (Unfortunately, practice alone isn’t enough for most people to learn good writing – some training is necessary, and many universities skimp on composition requirements and training by people who are trained to teach writing. But, even given that, writing assignments can be useful on their own.)

Absolutely! And there are plenty of ways to get undergrads to develop philosophical writing skills besides term papers or long-form essays open to the kinds of cheating mentioned in the OP.

So, some students cheat, so to stop them I should give my students and me a shit ton more work?

Pass, on ethical grounds

I don’t get how this is ethical, Jason. A system exists to help ensure that people who have acquired adequate skills and knowledge, and only those people, receive a credential. You and I are fortunate enough to be employed in that system, and to be given a good deal of discretion in ensuring that that credential is awarded properly and fairly. We are aware that there are many people out there who blatantly attempt to manipulate us into awarding that credential to them unfairly, and by that means they intend to defraud future employers, etc., Why is the ethical response to that to allow them to achieve their fraudulent aims without putting up resistance? Moreover, wouldn’t broadcasting the fact that one follows a maxim of awarding cheaters be apt to increase the number of your students who try to cheat, if anything, since apparently nothing bad happens to them if they do and they are apt to be rewarded more generously than if they put in the work?

I can imagine your students reasoning similarly: “So, I’m supposed to earn my grades without committing fraud, and to do that I should devote a shit ton more work, at the expense of being a better friend, etc.? Cheat, on ethical grounds.”

I don’t think the supposed ethical costs of letting some students cheat their way to a degree (or rather, cheat through whatever portion of the degree writing assignments constitute) outweigh the extra work it’d take to stop them from doing that. Especially if you are as pessimistic as Jason Brennan and other DC-area libertarians are about just how well universities teach “skills and knowledge,” it seems like the fact that some students complete some of the requirements for a degree by cheating just shows that employers must not care too much about that possibility. It’s not like cheating is a big secret that only we academics are aware of — employers know people can do all kinds of illicit stuff to get a degree. It seems like that knowledge must just already be priced in to the value of a degree, and apparently it isn’t too big an issue. And that seems right if what degrees signal isn’t actually useful skills and knowledge, but rather stuff like the ability to follow directions, to stick to something for at least 4 years, to sit quietly and listen to someone boring talk for about an hour at a time, etc.

Whether we should project an atmosphere where cheating is accepted is a separate issue. Obviously *that* would be bad. So we should do something to make sure we don’t project such an atmosphere; but it seems like that’s already accomplished by simple things like putting stern warnings on your syllabus and walking around the classroom while students are taking tests. What it takes to make students *think* cheating is not acceptable is clearly different from what it takes to *actually* catch and punish cheaters, and it’s the former that seems to matter more.

I think the idea of JB and others (Surprenant, Bowman) instead is this: These essay mills are terrible. Already they are damaging one aspect of our colleges, the grade and credential apparatus. If we react by changing the way we teach and what we teach, then their damage will have spread to a much more important feature of our colleges.

The job of a teacher is to be expert in a subject matter and to teach it well. When we do this effectively, the education we provide is worth credentialing in the first place. Of course some students will show up largely or even solely because they are interested in the credential. Some of them will cheat and some of them won’t, but the more our pedagogical efforts are devoted to managing these ulterior motives, the less likely we will be effective as teachers.

Others have pointed out that assignments that can’t be hacked might actually be better for some learning purposes. If so, then the fact that paper mills might have inspired us to conceive of such assignments is a happy accident. The reason to teach with them is that they are effective for the students who are out to learn, not that they can’t be hacked.

Philodorus: The problem of academic dishonesty is getting worse and worse, and at this point 2/3 of undergraduates are guilty of it, even by their own admission (https://academicintegrity.org/statistics/). So why do employers continue to take academic degrees seriously at all? Partly because the numbers aren’t even higher, but mostly, it seems, because there is no other easy way to limit the pool of candidates at the start of their careers for interviews. But we’re on very shaky ground there. Selling great education at bargain prices has been tried (the early MOOCs), and it turns out that, without the credential, it just isn’t that marketable a product. Once the levels of dishonesty get high enough that the credential ceases to signify anything, families will realize that it isn’t worth it any longer to spend vast sums of money and incur large debts for their children to have that credential, and there goes the university as we know it. And in fact, what’s anticipated to be a significant drop in enrollments has already begun. Will the degrees at least continue to indicate a willingness to sit still in class for four years and follow instructions? Not if we give out the credential to people who simply skip class (or attend but play video games the whole time) and just turn in plagiarized work and cheat on exams.

University Teacher: ONE job of a teacher is to know the subject matter and teach it well. But it’s not the only job. We aren’t just employed to teach our students: we’re paid to assess them fairly. There’s no need for both those jobs to be done by the same person, and perhaps it would be better if we only did the teaching part and the examination could be done by someone else. But as it stands, a big part of the job we’re entrusted with is fairly evaluating our students. If we fail to do that, we let down our honest students, encourage wrongdoing, and allow the system to collapse.

One strategy I use: collect the papers as docx files and check the metadata via File / Properties. What name is stamped in there? Also, some cheaters do know about that strategy and will purge all metadata (handled under “Protect Document” then the checkbox “Remove personal data…”) But that also indicates something. You’ll get a document that has no metadata and took “0 minutes” to write. No student does that by accident.

Had a student recently who turned in a paper with all metadata wiped. I strongly suspected that meant it was ghost written. I asked her about it and she played dumb, saying she didn’t know how it happened that the metadata got wiped. But, before the conversation turned south, she offered to re-write the paper. What I later got was very different than what she originally turned in…

Students have always cheated, but my sense is that in the last 30 years cheating has become more prevalent not just because it is easier for students to do, but because we as a society have become even more dysfunctional in our conception of education as *merely* ways of obtaining a document that allows you do other stuff, which unfortunately is also something that want to do just in order to get another result. One thing that might help here is to begin class with a good discussion of Marx on alienation.

Have your students “build” the paper during the 3-4 weeks leading up to the date the final version is due. One way they can do this is through short in-class writing assignments (“come up with an objection of your own to this view that you could potentially use in your paper”), which can then become the basis of small-group discussions (“talk about your objection with the person next to you”) and broader class discussions (“let’s list some of your objections and then try to come up with some possible responses”). Use this tactic primarily because it is good pedagogical practice. Producing a good philosophy paper depends on building it one step at a time, on discussing it with your peers, anticipating possible objections, etc. Students should think about philosophy as a process and not a product, right? Also, it will give you as the professor important feedback on how the students are processing the ideas you discussing in the class and that will be the basis for the paper. Since the students are involved in the process and see that you are invested in this process yourself, and because they have already produced parts of the paper and you have seen what these parts are, it will reduce plagiarism to nearly zero.

Does anyone know *why* there is an increase in using these paper mills for ghost writing? I would be interested to learn more about the reasons. – My hunch is that students want to get good grades that way. If this is correct, it might be an idea to reduce the amount of graded essays (and focus on giving substantial feedback instead). We’d kill two birds with one stone: reduce the incentive to cheat and foster writing skills.

From an administrative point of view, the essay mills are quite useful as they contribute to earlier graduation rates – students are able to take and complete more courses at the same time. Moreover, the cost is comparatively low and, in any case, not to the university budget. The papers are also easier to read and grade, lowering the time cost of grading to the professors and T.A.s. so it’s basically a win-win situation.

Out of curiosity, I had a look at several sample essays at a couple of the most prominent ghostwriting websites. They’re of pretty poor quality (see for yourself), so I’m not too concerned about this. (My apologies if this post will be a duplicate. My previous post seems not to have been approved for some reason, so I’m trying again.)

Suppose that you’re a C+ student, and you do not have time to write the last paper for PHL300. Do you want the essay mill to write an A+ paper for you, or a B- paper? I suggest the latter: you’re much less likely to be caught. And it will suffice for your purposes. So, maybe the poor quality of the essay mills’ papers is a feature, not a bug.

On the campus of University of Toronto I see advertisements for essay mills all the time. In the lobby of one of the main lecture halls on campus, at the beginning of term, the tables are littered with cards advertising “Not Enough Time to Write your Essays and Assignments? $15 off essay! No plagiarism.” Talk about ‘luring students into it’!

All of the proposed suggestions strike me as quite difficult to implement in a 300-person lecture class, a class graded by TA’s with a specified number of hours for grading, or taught by a sessional instructor with 4-7 other courses to teach, never mind when all three are true. Given the percentage of student’s whose primary philosophy experience comes in classes with some or all of these features, I doubt that essay mills could be eliminated even if all the upper-year small courses taught by tenured faculty adopted all of these solutions. Which in turn suggests that individual action among those positioned to take it can’t be the fundamental answer to the problem (although it might help to some degree).