Did I Miss Anything? On Attendance

“Did I miss anything?” It’s a common question from students.

How do you answer it?

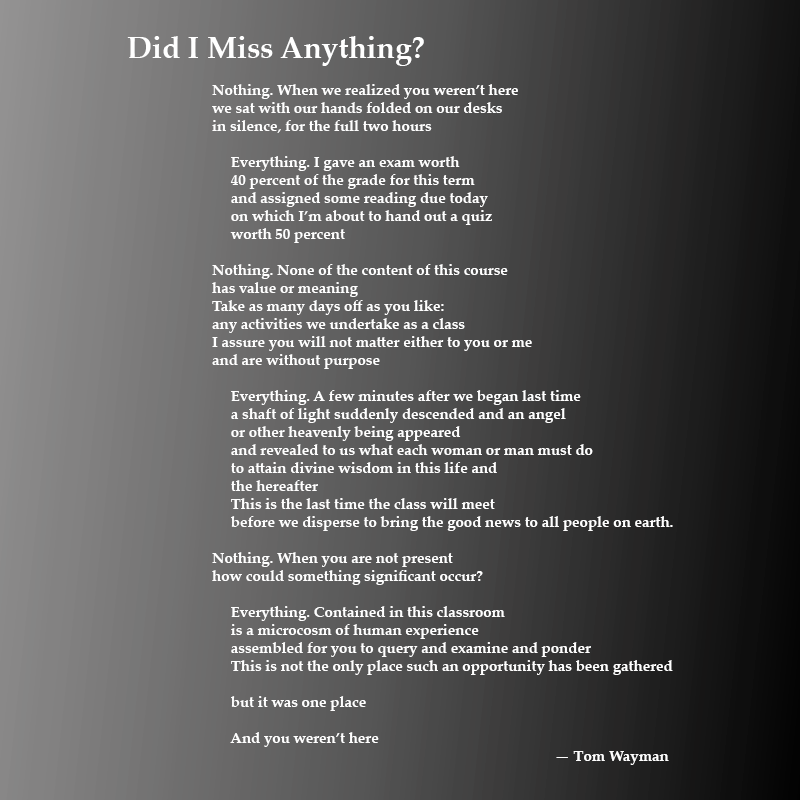

You may try directing them to the following classic response from Tom Wayman (Calgary):

How concerned with attendance should philosophy professors be? Philosophy centrally involves learning certain skills and developing certain attitudes. As with most skills, exercising them and witnessing others exercise them is crucial. Since the classroom is the primary arena for that, I think philosophy professors should think student attendance is very important.

What steps, if any, should one take to encourage attendance? Which are effective? Which are too paternalistic?

There were some interesting comments on the subject in a discussion here nearly four years ago, which I excerpt below, but as the audience for Daily Nous has grown somewhat since then, I thought it would be worth revisiting the topic.

M: “I take attendance in large lecture classes (60-120, in my school), but not in small ones, and I back it up with draconian penalties for missing class without excuse. Students get three free absences for the semester, but after that, for each unexcused absence, the student’s COURSE grade drops by one-third of a letter grade. I don’t fail anybody for attendance lapses, but students can drop down just short of failing. My rationale is partly just paternalistic: I am solving the puzzle of the self-torturer for them. But part of the rationale is that I do not think that I am just delivering a service, which they can avail themselves of at their own discretion. Even a large lecture class is made much better by students raising questions for discussion and clarification. So students are not doing their share for the good of the course by not showing up consistently, and I don’t think that there is anything wrong with requiring students to do their share for the course, on penalty of a drop in their course grade.”

Eddy Nahmias: “In my classes I have some minor assignment that students must turn in in person (usually I take up only about half), such as short reading questions or a question about the reading. Hence, students lost points for failing to attend and for failing to do the reading. I can’t see why we would not want to encourage attendance in this or other ways. It improves classroom discussion and student performance. Yes, students are adults. And adults have attendance taken… at their jobs.”

Dale Miller: “I understand the point of view of those who take attendance on the grounds that students who fail to attend have a detrimental influence on class discussion and morale. My own experience, though, is that having students there against their wills and visibly disengaged is even more damaging to the atmosphere. Reasonable instructors can differ, I think, about which effect is more toxic, especially since this probably depends largely on what pisses the instructor off (or at least distracts her) more.”

Gary Bartlett: “I kill two birds with one stone: at the start of class I pose some questions on the reading assignment that was due for that period. (I use clickers for this.) And their performance on those questions counts significantly towards their grade. This both motivates them to attend and motivates them to do the readings—two things that very many of my students would otherwise often not do.”

Av: “A couple commenters… say that it is the students’ choice whether they wish to attend classes and thus succeed, but that seems to assume that succeeding in a class simply means doing well on exams/papers. But that is a false assumption—perhaps dangerously so. (It certainly relies on a great deal more confidence in the thoroughness of one’s other assessment measures than I am able to muster about mine.) Succeeding in a class means learning the material. Those who do not attend classes regularly are likely (though of course not guaranteed) to have learned less than those who do attend regularly. (And are likely to have learned less of the material which is not tested on exams/paper assignments.) Thus if grading is a measure of learning, then it is quite reasonable to grade students on attendance, at least for most philosophy classes.”

Dana Howard: “I don’t take attendance directly, but I do incentivize it… Throughout the semester I have around 10 in-class activities: group activities mostly, close reading of a specific passage from the text, argument reconstruction, debates, comparing the views of different authors, etc… Student participation grade starts at full credit… every time a student misses a class activity, they lose 1 point. Final grades may thus be adjusted up or down by as much as one full grade for exceptionally consistent or inconsistent participation. I have found that this system is fairly effective in keeping students coming to class. Perhaps even more effective than when attendance was taken directly. Students like starting off with the 100% for class participation grade, they seem to care about maintaining their high average on this front, and they do not know when the next in-class activity will come.”

Discussion welcome.

P.S. Wayman answers some questions about his poem at his site.

While I have in-class assignments almost daily, I tell them rather emphatically on the first day, “If you don’t want to be here, please don’t come.” And I even have links to video versions of lectures available if students would rather just get the information that way instead of showing up. I find that students who attend begrudgingly are a buzz kill and ruin the energy of the entire room. I have strongly anti-paternalistic leanings on most of these classroom protocol issues. I also tend to think that the onus is on me to put something together worth showing up for.

“I even have links to video versions of lectures available if students would rather just get the information that way instead of showing up”

it is unbelievable to me that this is not a requirement of all lecturers at every college, or at least every public college.

if professors did this as diligently as they comply with title IX policies, colleges across the country would be profoundly more efficient and far more hospitable to low-income students.

I want to acknowledge first that many of us are bound bound by university and department policies regarding class participation grades and this affects what we are able to do with regard to attendance. I use two distinct tools, the first of which is a few years of data I’ve collected on the relationship between attendance and overall grade. I point out to students on the first day the strength of that correlation hoping the impress them the importance of coming to class. The second tool is roll call questions. I’ll write a simple question on the board, sometimes philosophical, often silly, and have them answer as I call their names. I find this encourages speaking up in the class as well as allows me to take the attendance for my records. I must state explicitly that this only works well in class periods that are over an hour and fifteen minutes long and have less than 45 or so students. Otherwise, it takes far too much class time. Generally, I do not use attendance to grade participation (unless directed to), but I do use it when I am considering changing a student’s grade or other minor corrections because I do take it as an indication of the students overall effort.

I’m quite interested in incorporating Dana Howard’s suggestion, above. I think I will try that in my next course.

I take attendance in my classes, for two reasons: it helps me learn students’ names faster, and it gives me a more objective means of grading participation (usually 10%). Generally speaking, I guarantee full participation credit as long as they come to every class and are not disruptive, not obviously disengaged, etc. I also give them the ability to “participate” in office hours, for those who have things come up. If they don’t participate, though, all bets are off. I won’t directly grade on attendance (since some students attend poorly but participate fabulously when they do, and university policy prohibits it anyway), but I’ll use it as a way to sanity-check my participation grading.

I am always amazed at the extent to which attendance correlates to final grade even if it’s not included mathematically. Students who show up do better work, or students who care to do work show up. Either way, while I have to take roll for administrative reasons I find including it in grade calculations to be largely redundant. Some penalty for habitual absences does make for a nice shortcut on the other hand.

that is because attendance correlates with the personality trait conscientiousness, not because attendance has a causal effect on learning. if you highly incentivized the class around mandatory readings and made attendance completely optional and emphasized this point repeatedly, the attendance would not necessarily correlate.

“not because attendance has a causal effect on learning.” What’s your basis for saying this? If you aren’t there, you aren’t learning whatever it was we were doing that day. “Learning” in our field isn’t identical with “reading.” Class time isn’t just some redundancy over doing the readings. The model of some Will Hunting who reads the calc text once and then solves Nobel-level equations without ever enrolling is (a) extremely rare and (b) not applicable to philosophy discussions anyway.

When a student asks me, “Did I miss anything?”, I never take the question literally; I assume that the student knows they missed *something.* (It’s like asking “do we have anything in the fridge?” Wouldn’t it be annoying if the answer was, “of course! We have lots of oxygen molecules!”) Instead, I take it that the student is wondering whether they missed absolutely crucial, or any deviation from the syllabus. And so, I’ll often tell them, “no, not really.” And then give them a sense of what the class covered that day (“we went over Korsgaard’s “The Authority of Reflection.” You might want to talk to someone in the class, or me during my office hours, about the tough spots in that article”). Finally, I tell them that a lot of other professors get annoyed by that question, and why they get annoyed.

I agree completely with Robert Gressis’ approach to this question (and similar questions). The student knows what they are asking; we know what they are asking; they know that we know what they are asking; and so on.

But they may not realize that they’re being insulting, even if unintentionally.

Plausibly, whether they’re being insulting depends on what they mean. Since what they mean isn’t an insult, they aren’t being insulting.

Maybe you meant that they are likely to offend someone. I agree, but I don’t think we should be so sensitive as to take offense when a normal students says this. So I think that for the most part, the problem is with us when this happens and we are offended.

Is it your position that if they don’t mean to be insulting, it isn’t insulting? I’m actually somewhat sympathetic to that, but it’s a far cry from what they’re taught in freshman orientation. In any case, what I meant is, in said freshman orientation, someone ought to explain the many ways in which college isn’t 13th grade, which includes both that they have greater leeway for missing class but also that their default assumption should be that they did in fact miss something.

I’m with ‘guy’ and Dale Miller. I want students to show up if and only if they want to be there. I make a very clear case that they should always be there, and some of my courses follow a Team-Based Learning model that includes team activities every day and a peer review process that allows teammates to give each other something akin to a participation grade. But in other courses, like a big logic course I teach, I don’t require attendance at all.

One thing I do in the big logic course to encourage attendance is have a couple of students from the previous semester come to the first lecture and talk about why attendance made a difference to them. I usually pick one A student who will explain how much important material is in the lectures and activities, and one student who didn’t do so well and can be trusted to say, “I really screwed up by skipping class, and wish I hadn’t. Learn from my mistakes and don’t make them yourselves!”

I also sometimes write to my students after the course ends and ask them to write messages to future students. I post those on the course website the next time. Many of the students stress the importance of attending, doing the readings, and paying attention.

I don’t like the idea of giving the students any points for mere attendance, because I feel that gives the impression that sitting in a chair is a university-level skill. I want everything they get points for, even the easy stuff, to be something they didn’t already know how to do perfectly before coming to university.

As a very junior instructor, I struggle with the question of tracking attendance. Personally, I have strong anti-paternalistic feelings/commitments when it comes to teaching, but these don’t seem to play well in the context that institutional teaching takes place. There are power relations in universities that structure the relationship of instructor to student in ways that preclude a mentorship relationship that is… freely chosen, democratic, and guaranteed to be in service of learning rather than in service of getting a credential. It seems that in some cases (20%?) genuine learning happens *despite* the institutional structure that precludes me being fully honest with students and precludes students from being fully honest with me. I guess it seems that it’s a somewhat coerced or at least pressured relationship that occurs for most students; I can tell they feel coerced or pressured to show up and to do the work; it makes me feel that if they feel that way, perhaps the instructor-student relationship is not a relationship they should be in. It makes me feel slimy to then try to get them to stay in it. But this is what almost everyone, including most students, expect. And many don’t think of the experience in terms of a mentorship relationship at all… they are just “taking a class.” I ask myself if I can take myself to be just “teaching a class.” But I am constitutionally incapable of that. It’s the mentorship aspect of teaching that drives me (even despite myself), but it’s not possible to be in a genuine mentorship relationship with 30-50 students. So I do some form of carrot/stick/don’t care policy, as does everyone. Not sure what my point is here, except perhaps that scale matters, but I do spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about this problem.

Maja, you write

“It seems that in some cases (20%?) genuine learning happens *despite* the institutional structure…”

If you’ve already noticed that as a “very junior instructor”, and you nonetheless find you just have to engage in something genuine rather than play the silly game the bean-counters want you to play (and that the students have been taught is the only game there is), then it sounds as though you _are_ the philosophy instructor so many are merely paid to be. It’s wonderful that someone like you is in the profession. It’s an uphill battle much of the time, but there are pockets where your work will be appreciated. I wish you the best with it.

Thank you for that, Justin.

My main goal as an instructor is to facilitate self-directed learning in my students. I’ve never been able to shake the sense that requiring attendance is in tension with this goal–that it communicates to students that learning is something that must be forced. It’s primarily for this reason that I don’t require attendance, though I can see some of the reasons why others do.

Sorry for the double comment, but something else just occurred to me. Sometimes I wonder about a case in which a student didn’t show up to class much, but with the help of abundant reading and other activities outside of class, ended up turning in excellent work. (Let’s stipulate, too, that the work passed the plagiarism checker with ease, that it was in fact the student’s own, etc.) Were I to require attendance, presumably I would have to fail that student, or, at the very least, exact a sizable penalty on her grade. But, when it comes to a student like that, one who has excelled in her work and has clearly learned a great deal about the course topic (perhaps even more than many of the students who did regularly attend), exacting such a penalty seems wrong. The prospect of running into a case like this has contributed to my unwillingness to require attendance.

Here’s a real-life example of something like this case: There was a philosophy major whom I’d had in a couple of small classes before. His last semester in school he signed up for my large lecture logic class, a requirement for philosophy majors to graduate. I never once saw him in lecture, though he turned in all of his problem sets and did all right on them. The day of the final, he came up to me and apologized for not having been in lecture. He told me he had created a startup company with some of his friends, it was his employment plan for after graduation, and all his time during the semester had been devoted to it. He was taking logic just to meet the requirement and graduate, and he found he could get by by just doing the reading. He passed the final, got a middling grade in the class, and graduated.

I had no problem with that. I’m fine with trying to educate students about what’s most likely to optimize their learning in a class. But I no longer assume that that’s every student’s goal in the class, and I don’t penalize them if it’s not.

Agreed that works on logic, but I deny it works on courses where there are issues to be discussed.

Yes, I do think that we must distinguish between types of courses/classes. In my legal phil courses, or even ethics courses, I could never boil all that ‘happened’ or what I wanted us to discuss in class to some set of ‘exercises.’

Some anti-paternalism positions assume that students have an unconstrained choice—outside of instructor policies—as to whether or not to attend class, or that students’ choices on this issue are largely a matter of preference and prioritization. I find that this is usually false. Students have many and various external and intense pressures—some of which are quite pernicious. Students often want to attend class, but outside of “paternalistic” or strong incentives feel coerced by these pressures to skip class. Some sort of requirement or strong incentive in this sense empowers their agency.

I think this is an important point. Gray commented just above that taking attendance “communicates to students that learning is something that must be forced.” I disagree. That seems to me to assume a false dichotomy: that students must either attend class entirely of their own free will (i.e. be entirely self-motivated), or they must be compelled to attend (i.e. be entirely externally motivated). There’s a whole swath of middle ground in between those two, which a reasonable attendance policy occupies, by allowing the class to gain an immediate sense of priority for the students. Being truly self-motivated is rare. For us ordinary mortals (I very much include myself) a little bit of external motivation is a great boon. As James says, it doesn’t destroy agency; it empowers it.

Hear hear to both Gary and James. In my own efforts at self-teaching my biggest problems have always been that other things that are more pressing and immediate just get in the way even if I want to learn whatever subject. Unless I have some sort of external pressure or I’m incredibly interested (as opposed to just interested) other stuff just crowds out what I’m trying to learn. In fact, I’d bet many of us have agreed to teach a class just because it would force us to actually really learn an area of philosophy we wanted to learn but couldn’t get around to learning. (For instance, I agreed to teach a class on continental philosophy because I knew there was no way I’d ever read “Being and Time” otherwise.) As is often the case I think the strongly libertarian arguments here are based on a fantasy of human autonomy where will alone tackles all obstacles that’s just got no relation the messiness of reality. Moreover, this sort of thing sets up students to fail and then blames them for doing so.

I genuinely wonder whether your argument here applies to graduate courses in philosophy and if not, why not? I don’t see why it wouldn’t, yet my impression is that, for the most part, attendance policies for graduate courses are rare (my field is math where attendance policies generally don’t exist outside of K-12).

Candlesticks, I think that’s simply because if you’re in grad school, it’s assumed that you are far more strongly self-motivated to attend class than the average undergrad; so an attendance policy is unnecessary. Notice, though, that this doesn’t mean you are entirely free of any external pressures. (I’m not sure that the idea of such a _purely_ internally-motivated agent is coherent.) Even without a direct attendance policy, there are all kinds of external contingencies built into the situation that motivate you to attend: e.g. the money you’d be throwing away if you didn’t, fear of your professors’ disapproval, fear of having to go and get an actual job…. Those contingencies act less strongly on the average undergrad (they often aren’t paying their own way; they don’t care as much what their professors think, etc), hence the usefulness of a more direct inducement in the form of an attendance policy.

My question to Sam Duncan concerned his conclusion that “libertarian arguments” against attendance policies are based on a “fantasy of human autonomy” that “sets up students to fail and then blames them for doing so.” If a grad student routinely misses class and fails as a result (which certainly does happen), why is it ok to blame them for it when, in Sam Duncan’s view, had it been an undergrad, the failure should more properly be thought of as a consequence of the professor’s policies? I am really not seeing the essential difference between the two situations.

As a separate issue, your original argument concludes with the assertion that “Some sort of requirement or strong incentive in this sense empowers their agency.” I take it what you really mean is: applying a strong incentive will induce students to more often do what I believe is in their best interests. Or perhaps: applying a strong incentive will induce students to do things that, deep down, they really want, but lack the will to do on their own. Calling this an “empowerment of agency” seems very weird to me.

Oops, I should clarify that it was James that made the original “agency empowering” argument. Gary just endorsed it.

For what it’s worth I do think that professors are often too hands off with graduate students and do stuff in the name of “autonomy” that sets up graduate students to fail. (The practice some professors have of handing out incompletes to grad students like Halloween candy is one that comes to mind.)

But to compare students in a graduate class to the average undergrad is apples and oranges. The average grad student is highly motivated, has good time management and study skills, and is extremely unlikely to be working full time. Many undergraduates haven’t yet developed the soft skills they need to succeed and part of our job is to help them do so. Refusing to do that under the guise of autonomy is at best misguided and at worst just an excuse for lazy teaching. I’ve taken a few classes outside of philosophy in drawing and the worst ones were those where the teacher treated absolute beginners like we were grad students and refused to give us a clear framework or any real guidance. As a beginner you need to be told what to do to succeed in a new area of study.

Also, many if not most of my graduate classes had weekly discussion paper requirements that pretty much served as de facto attendance policies and even in the ones that didn’t it was pretty clear absences could and would be counted against me. Outside of places like Germany or perhaps UChicago in the States where they have the gall to call 30+ student lecture classes graduate classes I can’t think of any graduate class I’ve been in that didn’t have at least a very strongly implied attendance policy.

“Students have many and various external and intense pressures—some of which are quite pernicious. Students often want to attend class, but outside of “paternalistic” or strong incentives feel coerced by these pressures to skip class.”

What in the world could these pressures be that they are so strong as to override the free will of the genuinely interested student but can be so easily combated by taking attendance?

Any justification for strict attendance policies here that likens attendance to a job requirement is self-defeating; if the purpose of philosophy courses were job preparation, they wouldn’t be philosophy courses. They’d be finance, or accounting, or something else. (Moreover, the job analogy only holds superficially. Nearly every private-sector workplace I’ve commuted to does not mandate workers to buy parking permits, for one, and college classrooms are usually in an odd village square-like environment that poses commuting constraints that affect students differently, especially by income level. Most crucially, they actually pay their employees. This factor cannot be overstated.)

For me, though, none of these comments address the bigass elephant in the room: much of the time, there is no need to physically be in class. This is so much the case at times that physically requiring me to be in class feels like an insult.

For lectures, not only is it possible for the professor to upload a recording of their lecture, it’s such a sustainable and workable solution that it’s irresponsible not to do this — recorded lectures can be watched and rewatched anywhere. This is a glaring inefficiency that is forced on students and drains resources. Mandating that a student show up for this is indefensible. The purported reason is that students can ask questions about the lecture, but (1) few lecturers actually means this, as too many questions is “derailing” the lecture, (2) questions can easily be asked over email, and in fact this is easier to do if you can provide timestamps on a lecture recording, (3) it’s thoroughly possible, especially with 4G phone data, to provide skype Q&A sessions once weekly. But it’s clear that the lecture model is just habit for the most part, and any reason to justify it is a veneer because “well, it’s the way I’m just to doing things” doesn’t sound good enough.

For discussions, classroom attendance is more defensible, but it’s clear that without structure and methodology, class discussions can quickly become a waste of time too. For as much as philosophers write about the benefits of class discussions, not nearly enough in the profession write about how they can go wrong. Far too many classroom discussions are vehicles for students to rant about some topic, or guide the discussion off-course, or bullshit about things they’re pretending to understand, or make up for lack of reading by talking more in class, or any number of issues of this kind. There is frequently no model for the discussion that the professor aims to have. I’ve had some very good classroom discussions, but I’d say over 60% and perhaps 80% of the time they are a waste of time. (I also get a vaguely hypocritical vibe from professors who preach about diversity and inclusiveness while having strict attendance policies — I can’t think of anything more damaging to the prospects of low-income and disabled students. I don’t personally care about this, but if you do, perhaps reexamine your priorities critically.)

But even in the event that class discussions are a philosophical necessity, they can still be done through Skype. It’s 2019. Seriously. 4G data is everywhere and 5G data will be everywhere soon. There is no excuse to not be technologically literate. Online fitness coaches do this frequently, and technology failures are more of a gambit to hope the professor does not have the technical competence to solve the problem (such that the student can dip out of the discussion) rather than real problems. When people want to use Skype, they do, and once it’s properly implemented the financial benefits and time benefits clearly outweigh the downsides.

I want to comment on one part of this:

“But even in the event that class discussions are a philosophical necessity, they can still be done through Skype. It’s 2019. Seriously. 4G data is everywhere and 5G data will be everywhere soon. ”

This is just plainly wrong, and partially for a reason you yourself point out. I’m a PhD student and instructor at a R1 school which is in a place with terrible internet, to the point that I often have trouble Skyping into conversations. And it’s strange to assume that everyone has access to data, especially those who are low-income.

If you’re going to suggest an online alternative to class discussions it should clearly be a less technologically requiring solution, e.g. a message board.

The “terrible internet” factor is exclusive to WiFi, which is inessential for Skype classes to occur. I’ve used computers at a lot of colleges, and all of them had reliable ethernet connections to their internet in their classrooms. From there, it’s completely possible for the lecturer connect a Skype webcam either directly or using an extension cord. The access can occur any number of ways after that. I should also note that many classes I’ve taken — even normal on-campus classes — presume access to a reliable internet connection. If the college seriously cannot provide that, this is an essential aspect of education the college needs to fix.

Moreover, the costs of commuting to any given college campus are far more prohibitive than the costs of 4G data plans. Most poor people in the United States have some kind of data plan because without one, getting a job is extremely difficult — very few job applications aren’t online — and data plans are often the cheapest reliable internet connection they have that isn’t a library of some kind. This cost could easily be aided by schools in some way; it just isn’t, because the current funding structures incentivize the lecture model.

The efficiency of internet solutions to informational problems has been realized nearly everywhere except college campuses, and it *really* reads like a bunch of people in relevant-seats-of-power are just so habituated to a current model that they can only muster a token effort to do it any other way.

At my university, California State University, Northridge, if we put up a recording, we’re required to caption it, because of the ADA. Even if you know for a fact that all of your students can understand everything you’re saying without captions, you’re still required to caption any videos you post.

My classes range in time from 75-100 minutes. I can’t caption them–I don’t have the time.

We do have a captioning service that supposedly takes two days to caption things, but I’m skeptical that (1) this service would avoid making crucial errors in captioning technical terminology (e.g., “incompatibilism”) and (2) I would bet that if every professor recorded their lectures and had them captioned that it would start taking more than two days to put the lectures up.

Assuming that (2) is true, then one way to resolve it is to spend more money on the captioning service–hire more people, etc. But I do wonder if that if the best use of university funds.

This is a serious wonder–if students don’t have to show up face-to-face, then that will save a lot of money too; we wouldn’t need as much parking or to spend as much on gas, to name just a couple of factors. That said, there are valuable emotional components to face-to-face discussions that are absent from watching those discussions on video. But perhaps we overrate the importance of those emotional components.

I’ve read that when people read on-screen texts, they retain much less information than when they read one printed on paper. I assume this would be just as true of lectures, and more true of discussions.

I’m surprised people are acting as though most classes are lectures. My classes aren’t lectures, and I know many other professors who teach similarly. We do the work in class. Hence, if you aren’t in class, you can’t do the work. I make it clear that this is how I teach, and if they want a class that does not require in class work they can take another course (there are plenty of options). Indeed, a few students always drop. If you choose to take my class anyway, you went into it knowing how the game is played.

Although I sometimes grade participation and attendance, I don’t require it. How could I?

I’ll get to my stated policy in a sec, but the thing I try to get them to understand is that, at the end of the semester, what I’m looking it is “did this student miss class a couple times, or like 9-10 times?” If it’s the former, I don’t get bent out of shape at all. Of course there is such a thing as a good reason to miss class. But if it’s the latter, you definitely did not learn all the stuff you were supposed to learn, almost by definition. So I usually phrase it like “absences in excess of three will result in reductions to your grade,” but I also tell them to use good judgment and only miss if they really need to, not because of some competing good. Also, since most of my courses are not required, I remind them that they should want to come anyway. And I explain the distinction I just described, so that they know why I’m saying all this.

I haven’t really read any of the discussion after Gressis’s comment. Did I miss anything?

For those who might be interested in some scholarly work on this question, you should read Daryl Close’s “Fair Grades” (https://philpapers.org/rec/CLOFGF) and a reply by John Immerwahr, “The case for motivational grading” (https://philpapers.org/rec/IMMTCF). Also Jennifer McCrickerd, “What Students Deserve: A Grading Policy that Supports Learning” in Emily Esch, Kevin Hermberg, and Rory E. Kraft, Jr. (eds) Philosophy Through Teaching. (Philosophy Documentation Center, 2014), and (also by Jennifer McCrickerd) “What can fairly be factored into final grades?” (https://philpapers.org/rec/MCCWCB) These are not just about attendance, but get at the issue of the extent to which we grade attendance (and possibly other things) as a way of motivating students.

Thanks for these links Andrew. I was curious if you had any links to good empirical literature on this as well. It seems that much of the normative work you linked to ought to depend quite heavily on what pedagogical research tells us about different grading styles and their effects on teaching outcomes (if motivational grading really did tend to increase mastery of course material then it seems like many of the fairness arguments against it, grounded on course mastery, would evaporate – if the opposite were true the arguments would shift in the other direction).

I don’t know of any empirical work, CG. I’m sure it’s out there, though.

I teach Close’s paper in class and have students do in-class exercises about grading policies afterwards. Students typically seem to enjoy Close’s paper.

I am posting with modifications a comment that got me into a lot of trouble at ‘Philosophy Students Say the Darnedest Things’. Many of the anecdotes on that site deal with the colorful excuses students give for not attending class and the trials and tribulations of philosophy professors conscientiously trying to enforce attendance. I found this puzzling. Assuming they were not bound by external regulations, couldn’t those professors all make life a lot easier for themselves by NOT making class attendance compulsory? If you do all or most of tyour assessment via essays which students work on at their leisure, if you have clearly announced deadlines for handing them in (with a scheme of penalties for lateness plus an extensions policy that can be administered with a moderate amount of flexibility) then you don’t’ have to spend so much time and energy playing the policeman and can devote much more of your in-class time to well, you know, *teaching* . Of course idle students won’t turn up or won’t turn in their essays but then that it is their funeral. If my students don’t attend fairly regularly they miss out on a potential 2.5% that they could get from giving a presentation and a further 2.5% for class participation which I don’t police very thoroughly. (It’s really part of a dodge to incentivize them to give presentations on a maximum-carrot minimum-stick basis. I would much prefer to simply give bonus points for a presentation but our regulations don’t allow it. ). Big-time non-attenders are naturally less likely to pass the course, partly because they miss out on 5% of the mark for the presentation and/or participation, but chiefly because they miss out on the lectures and the class-discussions which my lectures are designed to provoke. And if they don’t submit their essays in a reasonably timely manner they are highly likely to fail. But they are mostly adults (I only get a few seventeen-year-olds) and it seems to me that this is their decision to make. It is of course a bit silly to pay for an educational service which you then choose not to make use of and if you are being subsidized to study by the state but are failing to do so, the state is within its rights if it eventually withdraws the subsidy. But it is not our job as service-providers to coerce people into making use of the service that we provide and that, in many cases, our students have already paid for. I should add that I get attendance rates at my classes of about 70%, that that class discussions are lively, that my student evaluations are generally good, that my pass rates are well within the university’s guidelines and that my students’ grade averages are at the upper end of what is considered normal at the University for Otago. (Furthermore since the marks for some of my courses are ‘moderated’ by colleagues at other New Zealand universities, I can be reasonably confident that my students’ good grades are not simply an artifact of my softness as a marker) Thus thirty years’ experience at a state university with a relatively unselective intake suggests that it perfectly possible to be a successful teacher *without* employing these coercive tricks. And if you can succeed as a teacher without playing the policeman, surely it is better to do so. If enough students turn up enough of the time to ensure that that the classes are viable as learning environments and if enough of them turn up enough of the time to ensure that your pass rates are respectable, it is better not to enforce attendance. For enforcement carries significant costs, both costs in terms of time and effort and, more importantly *moral* costs in that it tends to infantilize students and to undermine them as autonomous leaners, reducing them to the kind of person who wouldn’t consider engaging in any educational activity without an institutional incentive.

In my own case a major influence on my attitudes has been Cambridge education. In the 1970s when I was an undergraduate, the lectures (as opposed to the supervisions) weren’t much good and after the first two terms I largely stopped attending. I still did OK. When I related this anecdote at the perhaps inappropriate venue of the Staff-student Liaison for Otago’s Philosophy, Politics and Economics program, my colleague, the Professor of Economics, who is about ten years younger than I am and had studied PPE at Oxford, expressed surprise that I had lasted so long. He gave up going to lectures after the first two weeks.

Now the Professor of Economics and I had access to other means to get ourselves educated. I read widely, I conscientiously wrote my weekly essay for my supervisor (they are called ‘supervisors ‘ at Cambridge and ‘tutors’ at Oxford) and I spent a lot of time talking to friends who were as passionate about philosophy as I was. (Thus a lot of my education was self-education.) But I really did not think it necessary to waste much of my time attending formal classes. The system is different at Otago and it is much more difficult to succeed as a student without turning up to class. But ‘difficult’ is not ‘impossible’. I deliberately design my own courses in such a way that it would be *possible* in principle for a sufficiently diligent and intelligent student to pass them without turning up at all (a technique I learned from my days as distance educator at Massey University in the late eighties) and relatively easy for a reasonably competent student to pass whilst cutting quite a lot of classes. Though I think myself a pretty good teacher (partly because my teaching technique encourages a high level of class participation) I don’t think my students need to hear every single golden syllable that drops form my lips. If they can get by with doing the readings and writing the essays and perhaps talking to their friends, that is plenty good enough for me. I would be very reluctant to force my students to do something that I did not do myself especially as I managed to succeed as a student without doing it.

“If they can get by with doing the readings and writing the essays and perhaps talking to their friends, that is plenty good enough for me.” Then, with all due respect, what are you there for? If reading books were sufficient for getting an education, why should we even bother being professors at all? One answer to my rhetorical question is: the texts are often _really hard_, and part of our job is framing and explaining and suggesting lines of inquiry. Another part is _professing_ — sharing our interpretations and insights. If students think that’s all entirely dispensable because they can read the book (or Sparknotes) at home or watch Crash Course, they’re mistaken.

I can’t speak for Charles, but here’s what I’d say if someone posed the question to me: I’m there to facilitate learning. I can do so by answering any questions students come to me with (e.g., if they found a certain reading hard), by suggesting readings and other resources that I think would be helpful to the students, by helping them plan their work, by offering my honest feedback on their arguments, and so on. And all that is consistent with the approach described in Charles’s comment (and is consistent, further, with the thought that professors are especially well placed to do these activities well). For me, the goal is to be, as far as possible, someone who guides rather than imposes.

What am I there for? Short answer: To help the vast majority who can’t do it on their own. in the hopes that this will gradually enable them to become autonomous learners who can do it without much help.

Elaborating a bit on my short answer. What am I there for if it is possible to get by without my services as a lecturer? Answer: a) to help the vast majority that would find it difficult to do so, and b) to help my students become autonomous learners, so that in the future they will be better able to learn about all sorts of things without the expensive help of a paid professor. Now if a student can demonstrate her capacity to learn without my help – for instance by turning in decent essays without attending many of my lectures – she will have proved pretty conclusively that she does not need it, since she will have demonstrated that she is *already* an accomplished autonomous learner. So although I think that my lectures are generally useful, I don’t want to force my pedagogic attentions on those for whom they are useless.

What underlies this dispute is a fundamental difference about the teacher’s function. I think of teaching (at least wrt adults) as a matter of helping other people to learn, which is itself an active process. It is not a matter of forcing information, or even skills and habits, into other people’s heads. (Hence my disrespectful attitude to those of my teachers that I did not find helpful and my willingness, as an undergraduate, to substitute self-education in the company of my friends for attendance at formal lectures.) There is a famous couplet of Pope’s satirising the teachers of his day:

Placed at the door of learning youth to guide,

They never suffered it to stand to wide.

I summarise my own view with a variation on Pope’s theme

Placed at the door of learning youth to guide,

He kept that door conveniently wide.

However, I supplement this with a few more lines

Nay more, a barker he was wont to be

Inviting them inside that they might see

Learning’s delights, which to a willing mind

Are of the very best that one can find

And if the threshold proved a little tough.

A helping hand he hoped would be enough

To get them over. But ‘twas not for him

To *force* his students to do anything.

(Sorry about the assonance in the last line. Imitating Pope is difficult.) It seems to me that others operate with a different maxim

Placed at the door of learning youth to guide

They shoved them roughly to the other side.

Now I don’t deny of course that sometimes a shove is necessary. But the difficulty to my mind is that if you don’t walk through the door of learning under your own steam, you will be less likely – and perhaps less willing – to make good use of what you find on the other side. Furthermore there is a risk that you will be so ticked off about being shoved that once your teachers have departed you will walk back out through the door of learning never to return.

But if through learning’s door you have been shoved

You will not think that learning’s to be loved

And when your ‘guides’ no longer are about

From leaning’s door you’re likely to walk out.

I am with you 100% Charles. I barely attended and still got a 1:1, if anything, attendance requirements detracted from my education when it came to post-grad level (I would much rather be able to research according to my own schedule than be forced into a class I would rather not attend). There is a streak of market mentality here: lecturers can teach to an empty room so far as I am concerned, it is the unquantifiable benefits which result from being in an academic environment which really count. Naturally, students should be encouraged to go to lectures, and there should be (minor) penalties for not doing as such, but higher education is about finding your own, indepedent, voice and approach to life first foremost. This may be an old-fasioned view, but, speaking as someone born under the millenial star, it should not be considered out-of-date.

I was called in twice by the head of department for non-attendance during my undergrad and also had trouble, some years later, for non-attendance at post-grad (although this institution was, in my opinion, particularly strict). Mostly that was because I was doing a lot of drugs and/or drinking. One thing I would say is that penalties had no effect on me: I already felt bad for missing the lectures/seminars, so any additional punitive measure simply made me incredibly anxious. My advice would be, at the first instance, to contact students who are recurrent ‘truants’ to check if there is anything going on in their personal lives which has resulted in them not showing up. Only one lecturer ever did this in my case, and I did start attending her seminars afterwards – mostly because she genuinely seemed to care and I felt quite guilty.

Many of the comments above focus on attendance in terms of summative assessment, that is, the connection attendance should have to the final grade. There are some comments that touch on formative assessment, that is, techniques used to let the learner know how they are doing and how they could improve; formative assessment is typically not linked to summative assessment.

Some of the comments touch on the relation between attendance and pedagogy, including: the balance between lecture and discussion; the advantages and disadvantages of online learning; and a few comments about other types of pedagogical methods including “team learning,” etc. However, while instructional scaffolding is touched upon, it is not explicitly mentioned; this is somewhat surprising, because instructional scaffolding requires some sort of interaction between learners and instructor, and thus could be an important argument for requiring attendance.

I see some evidence of the underlying educational philosophies in some of the comments, e.g., I see some evidence for romantic naturalism, utilitarianism, etc. Not surprisingly, given that Dewey is out of fashion, I see almost no evidence for a progressive educational philosophy (“education is not preparation for life but life itself”). Curiously, an explicit discussion of the relationship between educational philosophy and approach to attendance is missing in the discussion — curious mostly because this is a philosophy blog. I am an educator, not a professional philosopher, but it seems obvious that someone with a romantic naturalist educational philosophy is not likely to worry much about attendance, while someone with an existentialist educational philosophy seems likely to be concerned with the implications of attendance, and someone with a truly progressivist (in the Deweyan sense) educational philosophy seems likely to strive for a very high attendance rate as a way of engaging learners in “life itself.”