Empirical Support for a Method of Teaching Critical Thinking

A few years ago, a meta-analysis of studies about whether colleges do a good job of teaching critical thinking revealed “no differences in the critical-thinking skills of students in different majors.”

At the time, I wrote “it appears that philosophers lack good empirical evidence for what I take to be the widespread belief that majoring in philosophy is a superior way for a student to develop critical thinking skills.”

Perhaps this is not so surprising: course subject matter may make some contribution to the skills students acquire, but more important to skill development, it seems, is how the material is taught. And as with other disciplines, there is quite a bit of variability in how critical thinking is taught in philosophy courses, and some methods may work better than others.

One method that now has some empirical evidence counting in its favor is argument-visualization. A new study published in Nature’s education journal, Science of Learning, concludes that having students learn how to map arguments “led to large generalized improvements in students’ analytical-reasoning skills” and in their ability to write essays involving arguments.

The study, “Improving analytical reasoning and argument understanding: a quasi-experimental field study of argument visualization,” was conducted by Simon Cullen (Princeton), Judith Fan (Stanford), Eva van der Brugge (Melbourne), and Adam Elga (Princeton), and builds upon previous work on argument mapping that Professor Cullen has written about here.

The current study improves on previous research, its authors say, by being a controlled study, by using a well-known reliable test of analytic reasoning, and having students train “using real academic texts, rather than the highly simplified arguments often used in previous research.”

The study took place over the course of a seminar-based undergraduate course. During it, students worked in small groups, with intermittent faculty assistance, constructing visualizations of arguments in philosophical texts. Using LSAT Logical Reasoning forms as pre- and posttests, they assessed the performance and improvements of the seminar students and the control group. They found that seminar students performed better on the posttest than they had on the pretest, and that the degree of improvement exhibited by seminar students was greater than that exhibited by control students. They also had students in both groups write essays, and found that, in comparison with the control group, seminar students better understood the relevant arguments, structured their essays more effectively, and presented their arguments more accurately.

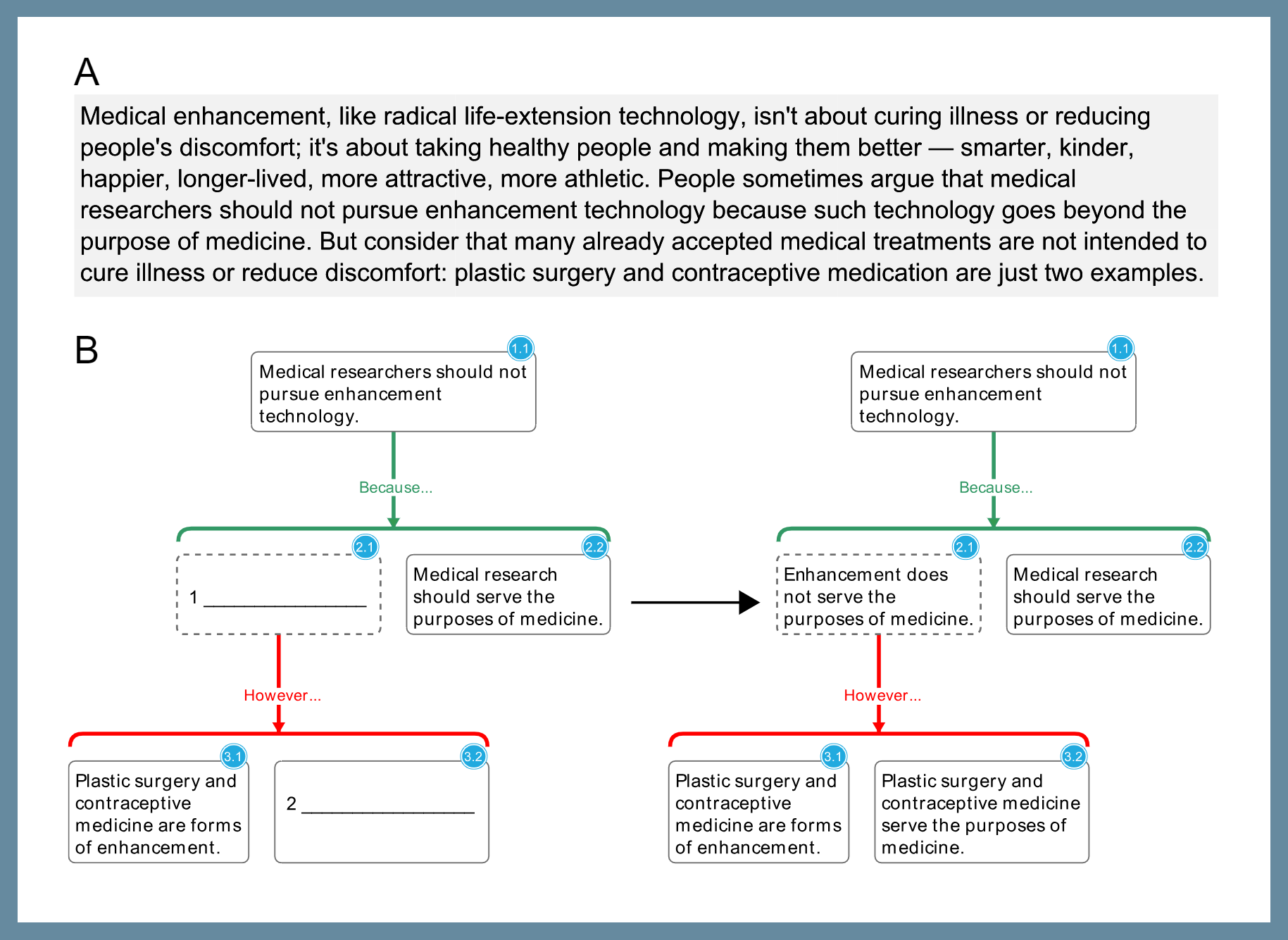

Below is an example of an argument-visualization exercise. You can read the study here. If you are interested in trying out argument-mapping, you may be interested in MindMup, a free online argument-mapping platform Professor Cullen helped develop (discussed here).

fig. 1 from “Improving analytical reasoning and argument understanding: a quasi-experimental field study of argument visualization” by Cullen, Fan, van der Brugge, and Elga

First, this is great. I have an objection that I think is weak, but I was wondering if someone involved or knowledgeable about this study could provide an answer: what if the improvement is just a result of training the very same skill that the LSAT test tests for rather than something like critical thinking more generally? Is it just testing the particular skill of argument mapping/argument schematization? Or is there a measure showing improvement in downstream critical thinking? I say I think it is a weak objection because I anecdotally believe in the power of doing this kind of exercise for improving critical thinking. It’s like the first step of slowing down that opens the door to a bunch of previously unseen features of an argument, opening the way for critical thought.

Hi C.W., thanks for your question. Transfer is the gold standard of evidence for learning, and that’s partly why we chose the LSAT for this study: the texts and questions it presents are seriously unlike those with which our students trained. (Our seminar looked nothing like an LSAT test-prep course.) It’s also relevant that we found large effects when we compared students’ essays with control essays drawn from a parallel course that did not feature argument visualization. I hope this helps to answer your concern about our choice of outcome measure!

HI Simon, congrats on this fascinating study. After reading it over, I do have one question. How were the treatment and control groups selected? If I understand correctly, the treatment group took a seminar on philosophy with argument visualization. But how did you determine who got into the seminar? Do you think that this affected the results? For example, if admission to the seminar was competitive, then perhaps the admitted students were more motivated to achieve gains than the control group.

Thanks very much, Sam! It’s definitely possible that selection effects biased our results (the study was a quasi-experiment), but we could find no evidence of this. As we report in the paper, the groups were alike with respect to their majors, their SAT/ACT-subject scores, and we controlled for slight differences in pretest scores. We selected students with the aim of building classes that would represent a variety of viewpoints, the thought being that this would make discussions and group work more interesting and productive!

Thanks to all the authors for such an important contribution to the profession.

I just based my intro gen ed course on argument mapping (AM) for the first time and was impressed with the results.

I was wondering if the authors might have a minute to respond to some comments/questions in the interest of helping AM newbies like me.

1. The study says that the texts to be mapped were adapted so students would be able to more easily interpret them, these being Princeton students. I wonder if the amount of adapting that would be required at colleges whose students are coming in with weaker reading skills would be prohibitive. Hopefully not! Any chance the adapted texts will be available somewhere? Any general tips on adapting texts? Do you worry that this aspect of the study might not generalize to students at more typical colleges? I ask because I’ve been toying with the idea of assigning more 1-3 paragraph sequences of arguments for mapping in place of full essays.

2. How do you get students to spend class time working on mapping the arguments (instead of gossiping, scrolling through snapchat, etc.)? One way would be to grade their work. But that would give the instructor a very heavy workload. I guess this is the age-old problem of in-class group work, but I wonder if AM provides any new solutions.

Thanks again!

To clarify the motivation for my second question, I have no misgivings about doing in class group work, in fact do it every class. What I’m wondering is whether this research suggests that these activities, in some form, can carry a lot of course objective weight. If so, they might be able to replace some homework, which would give some instructors more flexibility in course design.

Jonathan, it’s awesome to hear that you’ve been experimenting with argument visualization in gen ed! Have you thought about studying the effects of the training? Let me know if you want to talk about this!

About creating exercises for the classroom, I’d usually explain the background to the passages verbally before the students got to work, so they didn’t have to read too much of that. At least with Princeton students, about ~1k words/exercise seemed to work well. Sometimes we’d break a longer texts down into self-contained chunks that could be analyzed sequentially and then combined into a single map. Check the materials for teachers on Philosophy Mapped (philmaps.com) early next year – I plan to share whatever the original authors/publishers will permit.

About your second question, we didn’t have any big problems with students getting distracted in class. I think a few things helped with this… We always tried to focus on arguments they’d find fascinating, we used timers to ensure they were never left alone for much more than ~5 minutes, and we scheduled regular breaks during which they could snack and talk about whatever they liked. I think it’s important not to allow students to form their own groupings; instead, we’d paired them up and we’d reviewed how well the pairings worked each week, adjusting them as we learned more about the students. Maybe assessment could help, but I worry that it would be counterproductive: grading in-class performance may lead students to think of class mainly as an opportunity to earn praise from their instructors, rather than as as opportunity to develop their skills. In the Princeton seminar, we had a policy of not reporting any grades to students during the semester – neither for classwork nor homework. Some students were a little wary of this policy at the beginning of the course, but they usually reported deeply appreciating it by the end!

Hi Simon, I’m trying to get a sense of what you assign for the class. So, you assign full papers and you also give them short exercises? What role do the longer philosophy papers play in the class? How do students engage with them if they’re mostly focusing on the short exercises? Thanks for the help.

I am interested in studying the effects of argument visualization! I just emailed you.

Interesting study. A skeptic might say the students are just getting better at doing a fairly specific type of logic puzzle and the improvements likely won’t transfer. Another thing a skeptic might say is that the effects will likely vanish in a year or two out.

Bryan Caplan is one skeptic who often says things like this about the idea that the value of general education is that it makes students generally smarter or more critical, better at learning other subjects, etc. He talks about this in his recent book The Case Against Education.

Caplan cites psychologists who study such things and the findings he discusses are pretty dismal. He reports psychologists have found basically no evidence of transfer— students get better at a specific type of task, but however good they get at that, they get basically no better at other tasks . He also portrays his take on the psych literature on this as in line with the mainstream view.

Does anybody better versed in this area than I am know if he’s right or wrong about this?

I see Simon already answered one of my questions above in his reply to C.W.’s similar worries: the argument mapping course and the LSAT are pretty different, so it seems like transfer is going on. Thanks Simon!

So would psychologist consider this a rare and miraculous thing, as Caplan seems to suggest, or are psychologists much less skeptical about transfer than Caplan says they are?

As the authors of the study under discussion note, their research adds to an existing body of research on critical thinking and education. I think this research shows fairly convincingly that typical philosophy courses have a small effect on student critical thinking and that argument-mapping-based courses have a large effect. I also think the research shows that it’s pretty easy to devise a standardized critical thinking test that measures important skills with broader academic and real-world application. Critical thinking seems to be valuable just as one might have expected: if you can follow arguments and evaluate their strengths you’re more likely to infer true conclusions and inferring true conclusions can help in any domain.

As far as I know, there is no research on how long the increases in critical thinking due to education last.

I I would recommend, in addition to the OP article, van Gelder’s “Using argument mapping to improve critical thinking skills” and Butler et. al’s “Predicting real-world outcomes: Critical thinking ability is a better predictor of life decisions than intelligence.”

Thanks for the recommendations. I’ll definitely take a look at these.

The texts and questions on the LSAT LR forms are *very* different to those we studied in the course, but in both contexts it’s critical that students can identify the logical parts of arguments and how they hang together. So I think that we have here an example of students developing a set of topic-neutral skills in one context and them applying them in a very different context.

Sounds good to me. Hope you keep up the interesting research. Thanks for the response.

I’m not a psychologist or an expert, unfortunately. But I have read some cognitive psychologists who disagree with Caplan–to some extent. Yana Weinstein and Megan Sumeracki discuss transfer in Understanding How We Learn: A Visual Guide. They argue that there’s evidence that effective learning techniques promote transfer (like frequent retrieval practice and the use of many concrete examples to illustrate a concept). Their discussion suggests that transfer is hard, but possible.

I’ve read Caplan’s book and was very much provoked by it. My take though is that Caplan has a fairly devastating critique of the average college education in the US. But I’m less sure what Caplan’s book tells us about whether it’s possible for colleges to promote generalized reasoning skills if they use effective learning strategies (which they often don’t). Maybe argument mapping is one such strategy.

Thanks for this.

Yeah, from what I remember try to rule out the possibility that we might one day find types of education that transfer. He does say something like psychologists have been looking for the holy grail of transfer for a hundred or so years and haven’t found it, so we can’t reorganize general education along those lines at present.

Edit: …from what I remember try to rule out the possibility that we might one day find types of education that transfer.

I’m interested in understanding if there has been research completed on the transfer of critical thinking and generalized analytical-reasoning skills to non-formalized settings. For instance, does this sort of education transfer not only to LSAT tests where one is relatively detached from the subject material of the arguments, or would these skills transfer over to being able to better analyze information about a political issue that one is particularly passionate about? I think many philosophers would like to maintain that critical thinking is valuable because it creates a more educated populace that is less prone to rhetoric and cognitive bias when it comes to navigating the world, and not merely performing well on standardized testing. A someone that also doesn’t know a lot about the empirical scholarship on this topic, has any research been conducted to suggest that (high quality) critical thinking education (or high LSAT test scores, for that matter) correlates with being able to better analyze information in non-formalized settings?

Having an ability and being robustly disposed to exercise it are two very different things, so I think you’re right to worry about whether students will exercise their analytical skills in contexts that don’t involve formal testing. We haven’t studied this and I know of no good evidence to suggest that it isn’t an important concern. (Diane Halpern has suggested that her CT test predicts real-world outcomes, but I find the evidence she provides seriously unconvincing…)

On the question of the long-term benefit of philosophical instruction, it’s worth mentioning some of the work that’s been done on philosophy education in primary and secondary schooling. From here:

https://quillette.com/2018/01/11/benefits-philosophical-instruction/

One of the most rewarding things I’ve done in the last couple of years has been the pursuit of philosophical instruction in elementary and high schools. As I mentioned in the thread on the APA grants from last week, given the state of job market, the patterns that are becoming evident in the market, and the glaring need for critical thinking in the public domain, together with the fact that it looks like early philosophical instruction makes a difference on subsequent cognitive development, it would be good if there were more support for projects like this.

That’s not to say we shouldn’t be pursuing similar goals in university education, of course, and I’m glad that studies like the one discussed in the OP are being done. There’s space for education of this sort on a number of fronts. I’ve taught logic and critical reasoning online for a few years, and this semester I introduced one of my classes Robert Bloomfield’s LAAP and crebitry framework. Adapted from principles of good bookkeeping in accounting, Bloomfield has developed a schematization for identifying and evaluating contributions to debate and conversation that distort the aims of the venues in which they occur – Bloomfield identifies such distortions as ‘crebit’, as the incoherent attempt to mix entries on the debit and credit side of a ledger.

In the last two weeks I’ve given my students assignments for identifying crebitry in a Daily Nous discussion thread and an exchange between a Sovereign Citizen and a judge. The analyses the students gave of the Daily Nous thread were surprisingly sophisticated, betraying a much more subtle appreciation of what was being said (and why) than one finds in the comments they were analyzing.

If anyone is interested in learning more about argument mapping or in incorporating argument mapping into their classes, I’d recommend checking out ThinkerAnalytix. They’re an organization that teaches argument mapping and critical thinking in high schools and trains high school teachers in these techniques. They have an online course on argument mapping, and a helpful compilation of the research on mapping in addition to Simon’s really cool study.

Would having students put arguments into standard/premise-conclusion form count as a form of argument mapping?

It does not, because argument maps visually represent structural features of arguments that are not visually represented in the standard premise/conclusion form (such as chunking premises into groups when they only jointly support a conclusion). These kinds of features also allow argument maps to represent complex lines of argument that have multiple sub-arguments in a manner that is much easier to parse and process than the equivalent premise-conclusion form (which would either just be one giant argument, or would have to incorporate some elements of argument mapping in order to chunk out the sub arguments and show how they feed into the overall argument). Argument mapping also can very easily an nicely differentiate objecting arguments from supporting arguments via visual cues such as color.

Justin, the link to the article (in your last intro paragraph) contains an “author-access-token” followed by an impossibly long string of code. The canonical and permanent link is:doi:10.1038/s41539-018-0038-5 currently mapped to sensibly-named https://www.nature.com/articles/s41539-018-0038-5 for reading online and https://www.nature.com/articles/s41539-018-0038-5.pdf for offline reading.

Simon, first, let me thank you and your team for this work. At this milestone, I would suggest focusing on the MIT-licensed open source aspect of your work if you wish to maximize its impact in ways you cannot imagine..

You might consider a DOI for the open source portion (mapjs at https://github.com/mindmup/mapjs ) of the proprietary code that powers the mindmup.com server – for those who don’t need classroom management features and for those who need or prefer offline use in any case. But first, please consider beefing up the install instructions for those new to node.js and npm.

Software used in academic research and teaching (including the several symbolic logic programs recently featured here on Daily Nous) deserves a truly permanent home and citable reference beyond (in addition to) GitHub – for several good reasons, your CV amongst them, but also including basic reproducibility of a specific study and a far stronger guarantee of permanent accessibility than GitHub alone provides. (GitHub repositories may be deleted at will of account owner).

May I echo Peter Suber in recommending the free, green access depository for code, data, papers, etc. operated by CERN: Zenodo https://zenodo.org/ I have more faith in this than any institutional depository on the planet. This best-of-breed free depository allows DOI versioning of an ever-changing linked GitHub repository. See the very short GitHub Guide, “Making Your Code Citable” at https://guides.github.com/activities/citable-code/ and the Help FAQ at Zenodo. Your code and test data (latter not necessarily open access, though its meta-data will be) could live in the same stable infrastructure that houses data for the Large Hadron Collider.Cool!

Great work so far; a little gold plating is in order. Let it shine! Thanks!