Article’s Acceptance “On Hold” Following Complaints on Social Media

An article that was accepted for publication in a special issue of The New Bioethics is now “on hold” following postings critical of the article on X (Twitter).

The article is “Abortion Restrictions are Good for Black Women” by Perry Hendricks, a recent PhD in philosophy from Purdue University.

Here’s the abstract:

Abortion restrictions are particularly good for black women—at least in the United States. This claim will likely strike many as outlandish. And numerous commentaries on abortion restrictions have suggested otherwise: many authors have lamented the effects of abortion restrictions on women, and black women in particular—these restrictions are bad for them, these authors say. However, abortion restrictions are clearly good for black women. This is because if someone is prevented from performing a morally wrong action, it’s good for her. For example, it’s good for Sarah if she’s prevented from driving home drunk. However, since abortion is morally wrong, it follows that it’s good for women when they are prevented from getting an abortion. And since black women get abortions at disproportionately high rates, abortion restrictions are good in particular for black women. Indeed, this is an example of a positive effect of intersectionality.

The paper argues for a moralistic paternalism, assumes abortion is wrong, and draws out the implications for that combination, contextualizing this within the rhetoric of contemporary political debates over abortion.

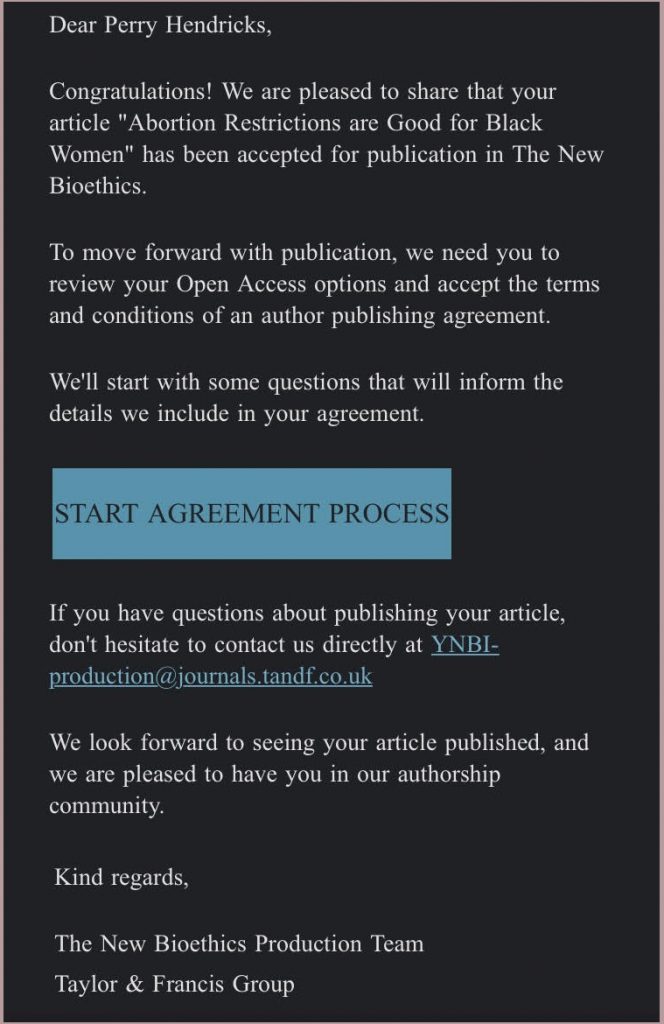

The paper was accepted:

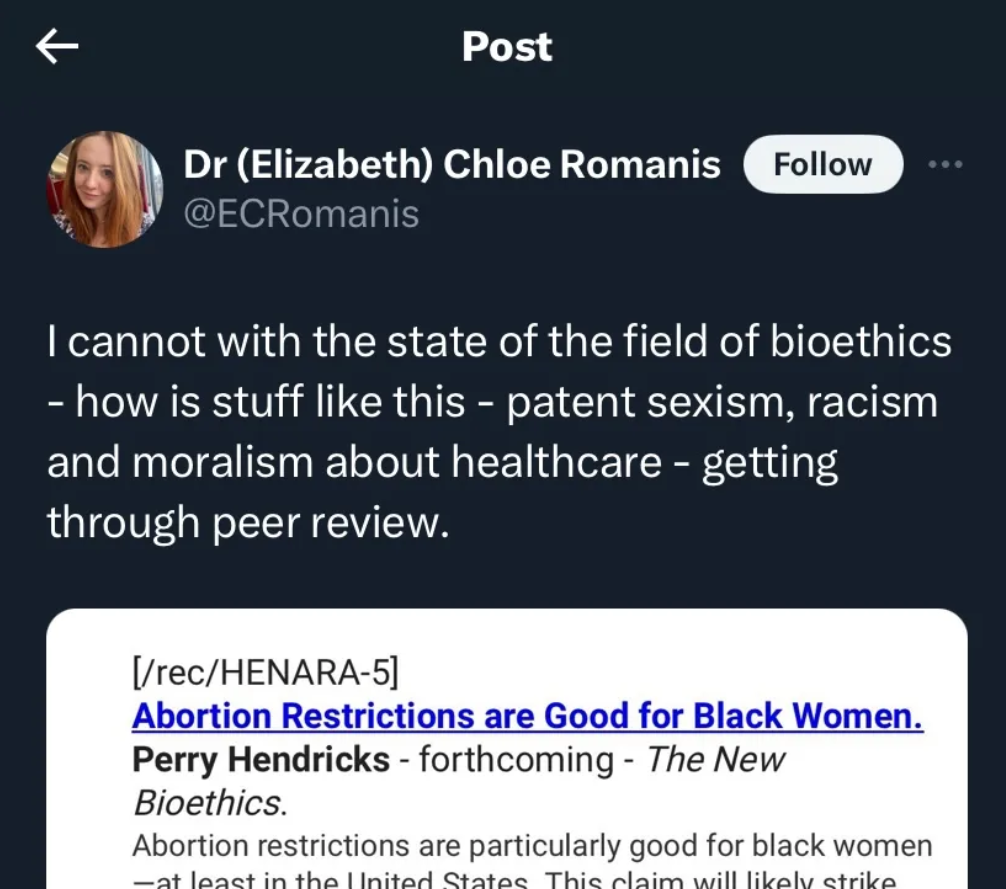

Hendricks listed the article as forthcoming. This was noticed by Chloe Romanis, a professor of law at Durham University, who wrote on X (Twitter): “I cannot with the state of the field of bioethics – how is stuff like this – patent sexism, racism and moralism about healthcare – getting through peer review.”

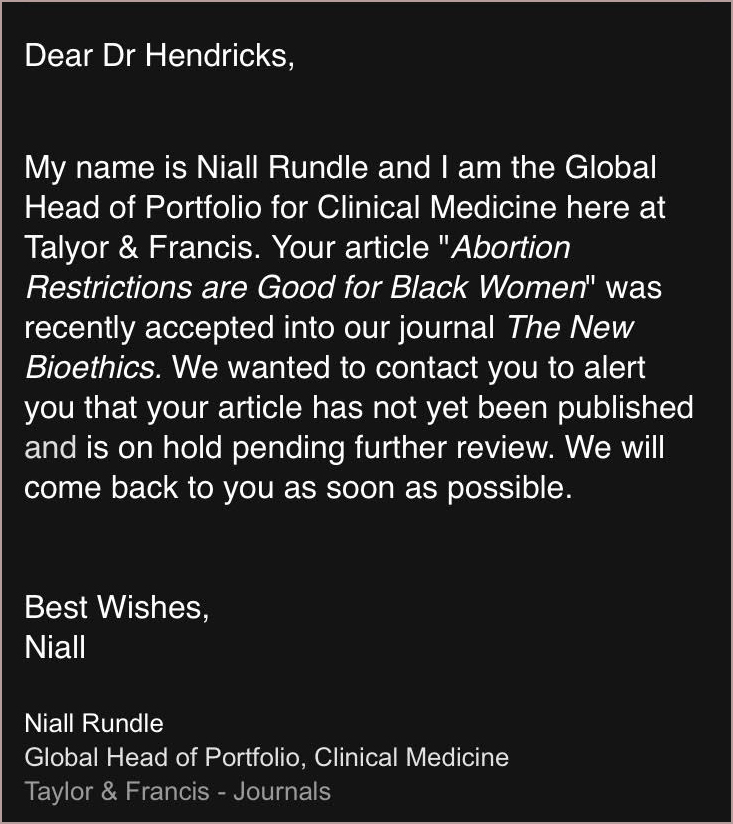

The comment, which was shared widely across X, was followed by an email to Hendricks informing him that the publication of his article was “on hold pending further review”:

Following an inquiry about this to the editor-in-chief of the journal, Matthew James (St. Mary’s University), I received an email from a Taylor & Francis “corporate media relations manager” who told me:

I can confirm that the article ‘Abortion restrictions are good for black women’ was put on hold after several complaints were raised. This is standard procedure for articles that are not yet published. A review of the editorial handling of this article found that it had been accepted for publication by the Special Issue Guest Editor. However, the policies in place at The New Bioethics require that the Editor-in-Chief, and not the Special Issue Guest Editor, must be assigned all articles for final approval before any acceptance decision. The Editor-in-Chief is now conducting this final review.

Readers may recall from this previous episode, which led to a profession-wide discussion of the editorial procedures at special issues of journals (see, for example, here and here), that it’s a good idea for editors-in-chief to be accountable for what appears in special issues with guest editors.

So is this just a procedural error? It strikes me as odd that the editorial software used by Taylor & Francis would allow for an author to receive an official acceptance of their article when the article has not been approved by the relevant parties.

But maybe that’s what happened. If so, it would be reasonable to think that it also happened for other articles scheduled for publication in this special issue of The New Bioethics, and perhaps previous special issues of the journal as well. It would be quite the coincidence if the only article for which this problem with the editorial process popped up was one that was complained about on social media.

That is, it’s not surprising that Hendricks’ provocatively-titled article drew complaints on social media that might have brought the procedural error to the attention of the publishers; but it would be surprising if it were the only article subject to that procedural error. If it were, that would raise other questions.

I asked both the Taylor & Francis spokesperson and the editor of the special issue, a current PhD student, how many other articles in the issue this had happened to, but have not yet heard back on this from either. I’ll update the post if I do.

Meanwhile, readers may be curious about the line in the spokesperson’s response to me, that putting the publication of an accepted-but-not-yet-published article on hold after social media complaints about it are raised is “standard procedure” at Taylor & Francis. I had not heard anything like this before, and I wonder how many people editing Taylor &Francis philosophy journals or submitting work to them or refereeing for them know about this.

For what it’s worth, I have received a message from a journal saying that my paper was accepted when it turned out to be a procedural error; the acceptance had been intended for another article, but was accidentally sent to me instead. Within a couple hours, I received an apologetic email from the editor letting me know about the error and telling me that my article was still under review. (My paper was not on anything politically controversial – it was mostly formal logic). Obviously I cannot speak to what happened in Hendrick’s case – or even to the frequency of erroneous acceptances – but it does happen.

Since the paper advances a false thesis, it’s clearly good for the author that he be prevented from publishing it.

This comment bothers me. I get that it’s attempting to be ironic, and the alleged irony is something like this:

“Hendricks claims that restricting abortion is good. He supports this claim by (1) assuming abortion is immoral and (2) arguing for moral paternalism. Ironically, if there’s a good argument for Hendricks’ moral paternalism, there’s likely a comparably good argument for an academic paternalism of the form ‘Stopping someone from publishing a false thesis is good for that person’. Next, we’re entitled to all the same philosophical moves as Hendricks is, so if he can assume abortion is immoral to make his argument work, we can assume his thesis is false to make our argument work. And voila, Hendricks’ paper provides resources for an argument against its being published!”

This irony seems misplaced. Hendricks explicitly notes in the paper that assuming abortion is immoral is not fair. What? Why would a philosopher explicitly make an unfair philosophical move? Answer: Because in the literature, many authors who oppose restricting abortion assume that abortion is permissible, and this makes arguing against restrictions a helluva lot easier. We shouldn’t make assumptions that make arguing for our views easier. To illustrate why, Hendricks offers an argument that assumes abortion is immoral and quickly arrives at the conclusion that abortion restrictions are good. In short, Hendricks’ paper is itself being ironic.

To support my interpretation of Hendricks, below is a quote from section 5 of the paper, which is titled “Objection: What if Abortion Isn’t Wrong?”:

The natural objection that will doubtless have struck the reader at this point is this: “You’ve not argued that abortion is wrong—you’ve merely assumed it is. And your entire case hinges on this point: if abortion isn’t morally wrong, then abortion restrictions won’t be good for women, let alone particularly good for black women.”

My response to this accusation? Guilty as charged. I have indeed merely assumed that abortion is morally wrong, and have gone from there. But I’ve done this intentionally: as seen above in Section 2, it is commonplace—though not universal—for authors to claim that abortion restrictions are bad for women, and in particular for black women. However, these authors don’t consider whether abortion is morally wrong—they just assume it’s permissible. I’ve intentionally mirrored their style here. The purpose of this is twofold. First, while it’s commonplace to say that abortion restrictions are bad for women, and particularly bad for black women, no one has noticed the corollary that holds if abortion is morally wrong. In other words, no one has noticed the important fact that if abortion is morally wrong, then abortion restrictions are good for women, and in particular black women.

Now, is Hendricks’ the paper actually good? Idk. Clearly, Hendricks is intentionally being provocative, to the point of risking offending opponents, and maybe philosophy papers shouldn’t do that. But the journal’s reviewers thought the paper was publishable until it got negative attention on X. Now the paper is being re-reviewed. In the event that it gets rejected, that would seem to me like viewpoint-based discrimination. And viewpoint-based discrimination is antithetical to scholarship. Indeed, viewpoint-based discrimination in is more of a threat to scholarship than bad scholarship (which the paper might be, idk). I don’t want to live in a world where only X-approved philosophy papers can get published.

“Viewpoint-based discrimination is antithetical to scholarship”. No it’s not. The opposite is true. Scholarship is predicated on some views being better than others. Why else care to consider evidence, have rigourous methods, make arguments, or have standards of reasoning? It is to discern truth from falsity, to discriminate between them. A diversity of viewpounts is not valuable on its own. Good, thoughtful, and well-informed argumets are, and if the result of making them is a diversity of defensible views worth taking seriously, then so be it, but such diversity it is not valuable in and of itself. If it were, then discrimination against creationism in biology and flat-earthism in geology would count as antithetical to good science. But it does not, and in fact such discrimination is a mark of a minimum standard of good scholarship as it is a result of adherence to what is actually valuable in projects of scholarship: Careful consideration of the relevant facts, reasons, evidence, and arguments to discren between true or false, good or bad, better or worse viewpoints.

Could it be that *philosophical* scholarship is predicated on some views being better *defended* than others? The standards you appeal to all happen to be broadly “formal,” or concerned with *how* (rather than *which*) conclusion is supported. But, presumably, “viewpoint-based discrimination” refers to the dismissal of a conclusion based mainly on its content, and thus largely irrespective of how it is defended. That is a (broadly) material sort of discrimination, which I assume some think occurred here, and which is unaddressed by your reasonable concern with more formal standards.

That said, it could be that this paper failed with respect to those standards. I haven’t read it, so I don’t know. But these Twitter-fueled issues tend to be (appear?) more sensitive to content than form. (And, of course, I will grant that the content/form distinction gets murky, and that perhaps this is a good test case for it.)

Also, for whatever it’s worth, I think I value a diversity of viewpoints in and of itself. But maybe what I value isn’t valuable simpliciter.

And yet a journal isn’t going to place an article initially approved for publication on hold because someone points out that it defends Kantian constructivism, which is false most of us agree. Why not? After all, it’s our job to discriminate between true and false! What goes for political articles should go for metaethical articles.

I think the answer is that, outside the extreme examples you mention, viewpoint discrimination is instrumentally bad. Also, deviating from standard publication procedures to appease those who don’t like the content of one article sets a precedent for potential abuse, even when the detractors have a point.

While many defenders of abortion rights also believe abortion to be morally permissible, I do not think many defenders of abortion rights believe these rights depend on the moral permissibility of abortion.

Just as a liberal society respects a robust range of freedom to say true and false things, it also respects a robust range of freedom to make (sometimes mistaken) personal choices about morally fraught questions. Boldly stipulating the wrongness of abortion at the outset of a paper gets you nothing but a tedious attempt at trolling the libs.

“Viewpoint-based discrimination is antithetical to scholarship”. No its not. Scholarship is predicated on some views being better than others. Why else care to consider evidence, have rigourous methods, make arguments, or have standards of reasoning? A diversity of viewpounts is not valuable. Good, thoughtful, and well-informed argumets are, and if the result is a diversity of defensible views worth taking seriously, then so be it, but it is not valuable in and of itself. If it were, then discrimination against creationism in biology and flat-earthism in geology would count as antithetical to good science. But it does not, and in fact such discrimination is a mark of a minimum standard of good scholarship as it is a result of adherence to what is actually valuable in projects of scholarship: Careful consideration of the relevant facts, reasons, evidence, and arguments to discren between true or false, good or bad, better or worse viewpoints

So ‘my opponents make mistake X, therefore I am entitled to make mistake X too’.

No. It’s rather “My opponents make mistake X over and over again, and they get away with it over and over again because people in this field and literature overwhelmingly agree with the conclusion supported by means of X. Now, watch me *also* make mistake X but to support a conclusion widely rejected in this field, and note how, when the conclusion is not something you already endorse, you can see that mistake X is transparently silly. So, making mistake X needs to be recognized as a mistake, and it needs to stop. This paper has exposed X as the mistake it is and is, therefore, an important intellectual contribution–far more important a contribution than all those other published (and not pulled at the last second) papers that got through peer review by making a silly mistake in support of a politically popular conclusion. This literature was in desperate need of a correction. My paper, if read correctly and taken to heart, does that.”

Making an assumption (implicitly) and building and argument from it is not a mistake, much less a silly one. It is an inherent part of literally any argument and occurs in every philosophy paper ever written, even for controversial assumptions.

That doesn’t appear to be what the title and abstract claim the paper will be doing. I would have expected someone who aims to make that kind of argument would have given some hint of this in the title or abstract, rather than saying in the abstract that they will be demonstrating positive effects of intersectionality.

I’m pretty sure he’s being ironic and just pointing out how the original logic is bad

There is no value neutral position in philosophy. We always have a position. Sometimes it is so commonly shared that the position isn’t noticed. Abortion is obviously a hot political topic. Position matters. Rather than assuming a both-sides ambivalence, it would probably be more appropriate to just layout out the differing assumptions between women’s sovereignty vs fetal sovereignty issue. History would likely disclose that the fight for women’s sovereignty has been around longer as a political cause than has fetal sovereignty. One might actually see that fetal rights were invented to counter the women’s sovereignty movement. It is a great example that changing the language of the position (a fetus is a child) is effective for obfuscation. The article in question seems to want to also change the language of the discussion. If one position is common, then the opposite position deserves equal consideration.

If it’s true that this paper is meant to be a kind of satire, this was not in any way indicated in the abstract. If it were satire, he should have made that point. The goal of an abstract is to give a summary of your arguments in your paper so a reader can know what to expect in your paper. If it’s satire, then he wrote a bad abstract and that’s on him.

I’m with you though – publish it. Let philosophers go at it. I could always use another publication.

A preprint of the article is available here: https://philarchive.org/rec/HENARA-5

Dr. Romanis’s post is spot-on and highlights a lot of problems with the article. I will pile on and add that is a surprisingly over-simple, weak argument for a philosophy journal. Here’s the gist of Hendrick’s argument. Abortions are bad. Abortion restrictions are good. Black women get abortions at disproportionally higher rates, so abortion restrictions are good for black women.

The philosophical jury is out with respect to whether abortion is bad or not, but even if it is, it doesn’t follow that a restriction against something bad is justifiable (imposing the restriction might be worse).

One might reply to Dr. Hendricks: the state of academic publishing in philosophy is bad. A restriction or policy limiting publications would be good. Dr. Hendricks publishes at disproportionally higher rates than other philosophers, so restricting his publications would be good for him.

Was the paper not peer-reviewed after submission?

This is not the argument of the paper. Did you actually read the preprint version? He explicitly acknowledges that whether abortion is bad is a contested issue. And I quote, “Of course, it’s contentious whether abortion is morally wrong. Nevertheless, [my argument here] shows that whether abortion restrictions are bad for black women depends on the ethics of abortion. And so we can’t–as some authors have tried to do–side-step this issue: to make claims about whether abortion restrictions are good or bad for women in general and black women in particular, we need to know whether abortion is morally wrong.”

Yes, this account of the paper’s argument is suspiciously at odds with other accounts in this thread…

As noted, I don’t think the problematic premise is “abortion is bad”. It’s the inference from “X is bad” to “a restriction on X is good” that is problematic. Also problematic is the inference from “X is good” to “X is good for someone”. Sections 3 and 4.

But I read the paper in propria persona and didn’t sense the irony. I read Section 5 as caution about the truth of a claim like “abortion is bad” and not irony. I’m not a bioethicist (or even a regular ethicist), so one could be excused for not picking up on that.

The abstract of the paper doesn’t suggest that it makes this kind of move.

But Bad Arguer literally quoted the part of the paper at which this move was made. Abstracts can’t cover everything. Or is “this kind of move” referring to something else?

But abstracts can and should cover THE MAIN POINT. When they don’t, that’s bad.

Sure, but Bad Arguer didn’t claim that it was the main point—only that the author does address the contentiousness of abortion, contrary to lol’s suggestion. And he does, as the quote shows. Did the author really need to include, in his abstract, that he at one point mentions that one of his assumptions is contentious?

Well, I suppose some interpretation is sometimes needed to discern the main point or points. That should have been better done here.

That’s what I said too.

username checks out

Justin, I sincerely appreciate that you posted about this.

I have serious doubts (but of course no proof) that the article was pulled both for its content and because of the positionality of its author (who is not, as best as I can tell, a black woman). I don’t intend here to comment on the substance of the article. Largely this is because I think, so long as someone produces an argument for a thesis that is accepted for publication, that the content of that thesis is irrelevant to whether it ought to be published. Controversy and truth often go hand in hand and it can be hard for people deeply situated in their sociohistorical contexts to separate mere offense from truth telling.

What I do want to do is to suggest that we adopt the following principle:

When something has been accepted for publication or presentation (article, book, lecture, etc.) then it ought to be published or presented as accepted unless one of the following is true:

(a) The acceptance was produced in a fraudulent or aberrant way relative to the standards of the journal / venue [This should be a really high bar. It must be proven that a genuine mistake or genuine fraud was committed]

(b) The article / lecture is itself fraudulent [This too is a high bar. By fraudulent I mean either plagiarized or written by AI]

(c) The venue has ceased to exist [i.e. the journal has been dissolved or is bankrupt]

No article or talk, ever, should be held back once accepted merely because others find it offensive or wrong. I take it to be the entire point of what we do that others will disagree with our ideas, that ideas that were thought to be dangerous or harmful at one time have become seen as orthodox or obvious truths at other times, and that the job of philosophy is to remind us that no ideas are obvious, that everything is subject to revision or modification in the light of new evidence or argument.

Others, in past conversations, have also rightfully noted that once academic publishers or conference organizers succumb to the demands of people on social media to cancel talks or not publish otherwise accepted work because they find it offensive is academic death because those in power (on social media or politically) will not always agree with our idiosyncratic moral views. You don’t want rightwing social media to have the power to influence journal acceptances.

I have read the paper. It does not meet my usual standards for acceptance. But, of course, I wasn’t one of the referees. I hope it doesn’t meet the usual standards for acceptance in the field of bioethics, because that would reflect poorly on the subfield indeed, but I don’t read enough bioethics to know about that.

A paper making this kind of argument could certainly meet those standards. A good example would be Matthew Scarfone’s “Incoherent Abortion Exceptions” (JSP 2020). Although Scarfone is by no means against abortion, he argues that, for those who oppose abortion on certain grounds, allowing exceptions is incoherent. Ultimately, he argues that those who favour such exceptions should instead be moved to reconsider their position on the issue. I can easily imagine a version of this paper that didn’t go on to flip those tables, though. And it would have been publishable too. But a paper which pretty much just pointed out the apparent contradiction and ended there would, in my view, struggle to justify its publication. My point is this: it’s good to have an interesting or controversial starting point, but how you follow through on it matters. Simply finding the hook is not enough.

Another good example that we’re all familiar with is Singer’s “All Animals Are Equal” which asks us to substitute ‘Black’ for instances of ‘animal’ in a paragraph by Stanley Benn. We can all see how horrifically racist the result would be so, by parity of reasoning, we ought to be worried about our talk about animals.

But the paper does a lot more than just highlight this reductio. In fact, it does a lot more positive work to justify expanding our sphere of moral consideration to include non-human animals.

To be clear, the author is not genuinely endorsing the argument in the abstract. They appears to be satirizing their opponent. They say that the near enough question begging form of their argument *intentionally* mimics what they say their opponents routinely do.

It’s a kind of turnabout thing: You don’t like this nutty argument? Then how come you do the same thing?

Here is the relevant bit in section 5:

But a person on Twitter “cannot” with it, didn’t you read the tweet?!

Why would you write a satire, but then not say anywhere in the abstract that this is a satire?

One potential reason for that would be that in this case the satire loses its effectiveness if it is signposted. Perhaps the effect the author was going for was a reader going through the first four sections without suspecting irony, becoming increasingly frustrated with the argument. Then in section 5 the author hits us with “Wasn’t it an unpleasant experience reading an obviously question-begging argument for a conclusion you disagree with on a charged political issue? Now consider the fact that people on the other side of this issue have to experience that all the time.”

Mentioning the intention in the abstract would have entirely robbed the impact of the ironic twist. Not saying this was clearly the author’s intention, but this is a possible (plausible?) answer to your question.

Because that wouldn’t be very satirical.

This question can’t be serious, can it?..

Given the passage cited by Sripada, it seems to me that the real core argument of the paper is:

Assuming abortion is seriously wrong, it follows (because it is generally good for a person to prevent them, in a suitable way, from doing doing serious wrong) that it is good to prevent (in a suitable way) women from having abortions.

The failure to mark the assumption as an assumption in much of the paper just allows the relevant rhetorical point to be clearly made.

A key unfortunate (and unwise) thing here was that the main point of the paper was missing from the abstract.

That main point was just that, for certain discussions about abortion, people just assume their preferred view on the ethics of abortion. So he explicitly did that in this paper, as some pro-choice people do, to make that point and observe that it’s bad. Mentioning that in the abstract would have been good.

One would think that the point of an abstract is to identify the major points of the argument and its conclusion. This seems like a significant issue.

Is it common practice to reject papers based on (perceived) problems with their abstracts?

Editors and authors should understand that abstracts serve a purpose and so write or develop good abstracts that include *the main point.* So this should have been noticed. This is especially important with papers on topics that “general readers” are apt to find of interest.

For those of us who do not use Twitter, can anyone say if Romanis shows any signs of having engaged with Hendricks’ paper beyond reading the title?

Not that we can tell.

Presumably they read the abstract as well, which makes the argument in greater detail. Others are saying here that the paper itself tries to take back all the arguments it makes in the abstract, and say that it’s just satire. But it seems like a bad idea for the main point of your paper to be missing from both the title and abstract.

Right. It seems to me that it’s a violation of “abstract ethics”! Really, an abstract must (accurately!) say what the main point is. Not having that is disrespectful to readers, misleading, and clearly does not result in the best overall consequences. It really looks like someone(s) was just foolish or “asleep at the wheel” here. Bad abstracts, especially on topics that people outside of philosophy are interested in, are bad for philosophy.

Some people here are citing a passage that amounts to “My argument is crap, but it is actually a strawman of the enemy, got you!”. Using this as a defence is puzzling. A strawman is still a strawman, even when clad in amusing rhetoric.

The strawman is never made explicit, but analogously to the given argument it would go as follows: “abortion is permissible; it is bad to be prevented from doing something permissible; therefore abortion restrictions are bad”.

But nobody argues this. Typically, the arguments against abortion restrictions turn on stuff like personal flourishing, individual autonomy, societal benefits, positive outcomes both social and economic, etc. pp. In a word, they are substantive, whereas the strawman is not.

Some works may proceed from a canon of such arguments. For instance, Watson 2022, cited in section 2 of the paper, frames her point largely in terms of autonomy, but focuses on concrete interventions to promote this autonomy. To say that Hendricks “mirrored” Watson is just plain inaccurate.

Certainly, one may go seek equally substantive counterarguments or, in actual analogy to Watson, focus on what follows from assuming a canon of counterarguments. But nothing of the like is attempted here (“it’s bad, so it is good to prevent it” ain’t it — this much, everybody here seems to agree on).

So the paper really is as bad as the abstract suggest, regardless of whether the abstract’s argument is read as sincere or as parodying the opposition. If it is sincere, it’s bad. If it is parody, it is parodying a strawman. Any qualified and attentive referee should have noticed that.

It is somewhat appaling that this needs to be spelled out. But it is indicative of a greater problem of conservative thought, namely that so much of it proceeds from the assumption that its enemies “get away with” things.

What evidence is there that “conservative thought” suffers from the problem you describe? I can’t think of any examples of this, besides maybe Hendricks’ paper, which I’m unsure you interpret correctly. This seems like a hasty generalization.

Re: my interpretation, you may want to look at Watson 2022 and then get back to me about whether the observation that a paper aimed at healthcare policy made a moral presupposition is something that (a) is in any way remarkable or problematic, (b) fairly challenged like this, or indeed (c) “mirrored” by the strawman.

Re: examples for my generalization, I’d point out that the first thing you reached for (above) is “viewpoint discrimination”. More generally, the relentless airing of grievances about alleged unfairness from conservatives — while in every case that has received any attention, the shoddiness of the work itself was the most parsimonious explanation. Moti Gorin below helpfully acts as another example, and cites a few more.

None of the examples I offered are examples where the “shoddiness of the work itself was the most parsimonious explanation.”

We have all read bad books and articles. Some of us have even written some (I know I have). The notion that “shoddiness” is the best explanation for why work that defends certain substantive positions that just happen to be unpopular with certain cliques in academia gets additional scrutiny is implausible.

Not that it should matter, but I’m a leftist and have no interest in promoting “viewpoint diversity.”

We’ll have to leave it at that, mostly because I don’t want to burden Justin with moderating a re-adjudication of certain matters.

“Moti Gorin helpfully acts as another example [of an aggrieved conservative].”

“I’m a leftist.”

“We’ll have to leave it at that.”

Lol wut?

It’s one of the matters I see no point in adjudicating, not sure what’s odd about this.

Doesn’t really need adjudicating. A simple “ah, my bad” would probably suffice (and not just saying that is what’s odd).

I simply don’t find the claim very plausible, but didn’t want to get into it.

Right, you don’t find it plausible that someone holds the political view they just ascribed to themselves. Hence, “lol wut?”

Yes because I am familiar with some of Moti’s work (yeah yeah “no true scotsman”). But there is indeed no point to adjudication on this.

The real point, anyway, is about the examples that Moti lists. But I figure we are all tired of talking about them.

It might be beside your point. But my point was that saying “we’ll have to leave it at that” in response to, admittedly among other things, someone correcting the political view you incorrectly attributed to them is—whatever you’re familiar with—odd enough to deserve a puzzled reply (namely, “lol wut?”).

If that makes you happy, fine.

It doesn’t make me happy. It makes me ask “lol wut?”

Not that it matters to the central point at issue (as you yourself note) but nothing I have ever written or said, sober or drunk, should lead any reasonable person to conclude that I’m a conservative.

Your original claim:

This is a generalization. If true, it discredits “conservative thought” somewhat (why would we hear out arguments that proceed from bad assumptions?). Given the weight of your claim, I asked for examples, so we can assess it in light of the evidence rather than rely on gut feelings.

Your evidence: I (above) stated that I’m worried that Hendricks, in the present case, is the target of viewpoint discrimination.

This is odd response for two reasons:

(1) You assume that my worry is misplaced, but I don’t see why that is. The facts are: Hendricks’ paper was accepted by the journal and subsequently pulled for re-review after it drew negative attention on X. Consider two competing explanations for this: (A) The paper constitutes shoddy work that shouldn’t have made it through peer review, and the backlash on X made the journal realize this. (B) The paper is, by this particular journal’s standards, of publishable quality, but the journal, seeking to safeguard its reputation, decided to re-review the paper in response to backlash.

If A is the best explanation, viewpoint discrimination has not occurred. If B is the best explanation, anti-conservative viewpoint discrimination might have occurred. We should note that it’s still possible on B that anti-conservative viewpoint discrimination did not occur. Perhaps the journal would have responded in the same way if Hendricks’ paper had instead angered a rightwing mob on X. Of course, that should still be concerning to proponents of academic freedom.

In my view, the evidence currently available renders the question of which explanation is best, A or B, indeterminate. You seem to be claiming that A is obviously the best explanation, since you reviewed the paper and think it constitutes shoddy work. But that’s a judgment call. I happen to think Hendricks’ paper is philosophically interesting independent of its conclusion. In light of our disagreement on this point, it seems hasty to conclude “A is obviously the best explanation.”

(2) Your original claim mentions “conservative thought.” I interpreted this to be a reference to something like “the conservative tradition in political philosophy,” which includes writers like Burke, Hayek, Oakeshott, Scruton, etc. If that’s what you meant, I contend that you will not be able to find examples to support your generalization. In that case, you stated an unsupported generalization disparaging a whole intellectual tradition, and that’s not very nice.

If instead you meant to say something like “It annoys me when rightwing philosophy professors air worries about viewpoint discrimination. There is no anti-conservative bias in academia, and every alleged example of discrimination is really just a case where someone’s work was revealed to be shoddy,” that’s fine. But why not just say that?

Sorry for being unclear. I meant that the current instantiation of “the conservative tradition in political philosophy” largely proceeds from perceived grievances and their adjudication, often but not exclusively focused on assumed “viewpoint discrimination” or the sense that progressives had outsized success with unreasonable arguments.

Witness just about any recent event put up by any conservative campus organization. Or anything said by Robert George in the last few years.

You are right that this is not so for Oakeshott, Scruton etc. (I have other issues with them, though I credit Oakeshott with convincing me that conservatism is a hopeless proposition, so there’s value there; the current strain, by contrast, is just infuriating).

“If instead you meant to say something like “It annoys me when rightwing philosophy professors air worries about viewpoint discrimination. There is no anti-conservative bias in academia, and every alleged example of discrimination is really just a case where someone’s work was revealed to be shoddy,” that’s fine. But why not just say that?”

I take this to be continuous with my complaint. The airing of grievances in comment sections, blogs, newspapers, talks, or articles is all equally indicative, to me, of the underlying problem.

“You seem to be claiming that A is obviously the best explanation, since you reviewed the paper and think it constitutes shoddy work.”

I believe that, and have argued as much in response to Moti’s claims about censorship, but this is mostly besides the point here.

My point in response to you specifically was that citing the “haha gotcha!” passage of the paper is not a convincing defence of the paper against its critics. And, moreover, that the displayed willingness to jump on this passage as a defence is indicative of what I see as a problem with contemporary conservative thought in general.

This statement disparages conservatives. That’s fine, but I dislike the vagueness. The vagueness makes it hard to assess whether you’re expressing a truth-sensitive proposition (e.g. “There is no anti-conservative bias in academia”) or a non-propositional sentiment (e.g. “I dislike conservatives”).

I am willing to consider the possibility that viewpoint discrimination played a role Hendricks’ paper being pulled for re-review after backlash on X. In your view, this is “indicative of a problem” in conservative thought. It would be nice if you could say explicitly what problem you’re seeing, preferably without making unspecific references like this:

We may be living in different informational environments because simply calling to mind examples of (1) events put on by conservative campus organizations or (2) claims that Robert George is known to make about the current climate on campuses doesn’t help me understand the “problem” you’re seeing.

Coincidentally, I saw George and Cornel West do a joint speaking event on “Restoring Civic Dialogue” at my university last September. I recall George claiming something like “Free speech on campus is under internal and external threat. Most external threats come from the right. Most internal threats come from the left.” This claim seems plausible to me. Idk if West agrees, but I recall he didn’t object. Is this claim by George “indicative of a problem,” in your view?

“expressing a truth-sensitive proposition (e.g. “There is no anti-conservative bias in academia”) or a non-propositional sentiment (e.g. “I dislike conservatives”).”

How about: conservatives [or however the ‘heterodox’ crowd self-identifies these days] are often falsely presuming that their views face opposition due to bias rather than due to intrinsic faults.

That’s truth-evaluable, but also something I find subjectively quite annoying. It does not entail that there is no bias in academia. Even in the presence of bias, not all negative treatment is ipso facto unfair.

Here is how I saw this reflected in the prior discussion:

The initial claim was “the paper’s argument is bad”.

The rebuttal was “it is, but it is aping a progressive argument”.

This rebuttal only convinces if one finds it prima facie plausible that progressives get away with things that cons don’t (that they are pursuing bad arguments without pushback). If one had any doubt about that, one might have followed up on one of the references and seen that it is nothing like that.

Hence, the whole charade — they very act of defending this particular rebuttal — evinces the presumption, held without double-checking, that bias rather than intrinsic fault is at play. Abductively, it contributes to evincing a tendency to attribute bias rather than fault more generally.

“Is this claim by George “indicative of a problem,” in your view?”

Yes, I think it is. It vastly overstates the “internal” threat and aims at diverting resources away from the much more significant “external” threat. And this mistake, I suspect, stems from George’s thinking proceeding from the assumption that the comparative lack of traction that his views enjoy in academia is due to bias rather than their intrinsic faults.

“You are right that this is not so for Oakeshott, Scruton etc.”

If Justin will permit a little more digression on this…

I’m not a Scruton expert but recently started listening to a collection of his essays on Audible. I also read his 2006 article “Should He Have Spoken?” If your idea is that, in contrast to the simple-minded grievance mongers, Scruton is some kind of serious thinker, I’d have to disagree.

So far, one of the central concerns of his work seem to be to attack liberals’ sacred cows and speak truths even if they’re unpopular with the current cultural elites. Everything is constantly couched in this kind of rhetoric. He can never just argue for p; it’s always (a wordier version of), “the libs won’t admit p because they’re so closed-minded and PC.” He might follow-up on one of those rants with an argument for p, but if he does, it will be exceptionally weak. He’s just clearly not that interested in first-order political or economic facts.

The other central concern is the preservation of Western Christian cultures and populations.

Look at “Should He Have Spoken?” The subtitle, “On the Household Gods of Liberalism,” says it all. Liberals, he tells us, are closed-minded about immigration. There’s this super important truth about immigration it that they’re unwilling to countenance. What is this truth and what’s the evidence for it? The “truth” is that a liberal immigration policy, which he doesn’t define, will admit too many terrorists and opponents of liberal democracy. The evidence for this “truth” is the London and Madrid bombings, the murder of Theo Van Gogh, that it’s evident to everyone, and that British politicians of the past would have grasped it because they learned the Bible and classics.

The parts about the classics are interesting. One finds a similar tendency among Straussians like Harvey Mansfield. They seem to want to talk about big, current political issues. But for whatever reason, they don’t want to analyze these issues through evidence, and instead go back to the classics. It all seems very posture-heavy to me.

The point isn’t to understand immigration and figure out how much and what kind of it is best for society. The point is to drone on about closed-minded libs and to fearmonger about foreigners.

I would speculate that the problems with his thinking derive from his basic commitment to Christianism, i.e., Christianity-driven politics. That’s not a position that’s going to win rational arguments about policy, so he retreats from both policy and rational argumentation.

I don’t intend to respond to comments, but it’s worth emphasizing that no passages in my article can reasonably be interpreted as racist or sexist. And no reasonable reader would think the article is racist or sexist. It’s unsurprising, then, that Romanis doesn’t cite any passages to support her claims.

does your writing evince a sincere concern for the well being of black women? if not then perhaps the construal of your explicit statements is beside the point.

I wonder why you’ve chosen to focus on Black women in your article, if your goal was to point out groups (or even “intersectional” groups) most likely to receive the good of being prevented from taking an immoral action. You singled out Black women by race rather than looking objectively at groups with the highest abortion rates, such as people with income below 100% of the poverty rate, cohabiting but unmarried status, already having at least one live birth, and so on. People have commented on the additional difficulties abortion restrictions present for those with lower incomes or who already have children, so it’s not as if an appropriate argumentative foil could only be found by choosing the example of Black women.

In addition, you assume that being prevented from the moral wrong of an abortion is a benefit properly applied to women, even though men often pay for abortions, help to make medical decisions, cause pregnancies, and are involved in other ways. How was the level of their benefit from prevention determined, relative to women?

If it is necessary to grapple with the moral wrong of abortion before making decisions about whether preventative laws are helpful or harmful, then wouldn’t we also need to know whether those laws actually do prevent abortion? If they aren’t very effective at preventing illegal abortion, how should this factor into the analysis of whether greater benefits are provided? Shouldn’t we also then consider whether the abortion restriction laws prevent or encourage other morally wrong acts, like self-harm, domestic violence, and murder? After all, pregnant women are much more likely to be physically abused and homicide is a leading cause of death for pregnant women. (https://www.bmj.com/content/379/bmj.o2499) The article assumes that unjustly killing a fetus is one of the worst things one can do, comparable to something like a fatal drunk driving accident – presumably killing a pregnant woman would be even worse, so an intersectional analysis focusing on groups at greatest risk might be needed. The article also appears to assume that every abortion is equally morally wrong, but this is not true for the state laws in question. Won’t we need to know which exceptions are made, and a subsequent intersectional analysis of which groups of people are more or less likely to be affected by those exceptions (for moral good or ill)?

[Just to be clear, I think it is wrong to rescind an acceptance of an article for ideological reasons. But I was surprised by the idea that no reasonable reader could find the article racist or sexist – mileage may vary but surely a reasonable reader could be worried about these issues.]

I do not want to talk about the article. But as the editor of a journal that is published by T&F (though not owned by them), I have to say the notion of a post-acceptance-prompted-by-social-media-furore-review is a new one to me. The contract between the AAP and T&F stipulates that ‘the editing and editorial policy of the Journal’ shall be the sole responsibility of the AAP, fully devolved to the editor (though there is reference to need for editorial decision to be in compliance with the ‘policies and procedures’ of the publisher). The ownership structure of this journal may be different and may not have this level of separation between publisher and editorial decisions.

Administratively, I can easily see how this could happen, assuming the journal is using ScholarOne to manage the editorial workflow – anyone granted the ‘Editor’ role can make final decisions on manuscripts, and if the guest editor account was set up with those permissions there isn’t any natural way to have those decisions be subject to further checks from the EIC. A good reason not to set up your guest editors that way, perhaps.

It’s not using Scholar One, it’s using “Routledge Submission Portal”. I have no experience with this one, but in Editorial Manager final dispositions cannot be set by guest editors, at least in the configuration I’m familiar with.

My mistake, AJP uses scholarone and I just assumed that was across T&F journals. But there are definitely limitations in the available roles in scholarone that I can imagine might make an EIC end up giving a guest editor more authority than they should.

We have several examples now (Byrne, Lawford-Smith, and now this one) of what appear to be, put most neutrally, unusual editorial/publisher decisions. Each piece of writing happens to defend views strongly disfavored by loud and aggressive proponents of the same set of moral and political positions.

The right is of course also guilty of censorship, or attempts at censorship, but I’m wondering if there are any recent cases in which right wing censorship has operated at this level, that is, the level of academic editors or publishers buckling to the hecklers. Genuinely interested in learning of any recent examples.

Does 2011 count as recent? Before Daily nous I guess

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/14/us/14beliefs.html

Sorry it looks like that’s behind a paywall

Here’s a link from old NewAPpS blog

https://www.newappsblog.com/2011/11/editorial-changes-for-synthese.html

It appears that the intelligent design controversy was also connected to a special issue with perhaps analogous issues to the present controversy ( except it was “right wing” rather then left wing “censorship “ as you call it)

Thank you. I now vaguely recall this story, which transpired when I was in grad school. It does strike me as a relevantly similar sort of case in terms of outside pressure influencing editorial behavior. I wonder, though, whether the Synthese editors ever considered pulling the paper, and also what would have happened if social media were a bigger force then.

Its a fair question – there was an outcry that a “disclaimer” would be inserted in front of Barbara Forrest’s essay critical of ID – I seem to recall there was pressure from Plantinga? (or others) – it did lead to a boycott of Synthese among some folks, and a resignation later of an editor… (John Symons..) I’m sure others recall the details better. But I think some editors were clamoring to pull the paper but it was too late (thus, the insertion of the “disclaimer” was discussed, etc).

Why presume there was any censorship? Admittedly, I did not follow the Twitter stuff closely, but I don’t recall anyone calling for a retraction or revocation of acceptance.

What strikes me as the null hypothesis is that a shoddy paper was accepted due to some oversight on part of the editor — either, as alleged, due to a technical error, or because the recommendation of an inexperienced guest editor was rubber stamped without diligence. Then, when the shoddiness of the paper became public knowledge, the editor went for damage control.

The null hypothesis is supported by the fact that The New Bioethics has published way more reactionary papers than this (that were however better crafted), and did not budge to complaints about them.

Nothing here smells censorious. The damage control was bad, however. Like Synthese did, it is better to let the mistaken acceptance stand, and change procedures to prevent reoccurrence.

It’s certainly possible that the acceptance was withdrawn for technical reasons. I suppose we could learn more, given Justin’s query with the relevant parties. For example, knowing whether everyone who got an acceptance in the same issue received the same email stating their papers also are “on hold” would certainly be informative.

As for why presume censorship: because we’ve seen very similar things happen recently that were pretty clear cases of censorship/attempted censorship, and because the PR person who responded to Justin stated that their decision came after complaints (presumably these complaints did not come from the peer reviewers or the editor, but from people who became interested via Twitter). We can argue about what censorship is, exactly, but I think it should be uncontroversial that explicit calls for censorship aren’t necessary for censorship.

Would you agree that there is a difference between an article being un-accepted in order to *appease* a negative public reaction (what you call censorship) and an article being un-accepted *after* a negative public reaction, e.g. because the reaction made the editor realize that the article is bad and it would be somewhat embarrassing to have it published (what nobody could call censorship). My point is that nothing points towards the former, but a lot points towards the latter.

The same goes for all other cases you mentioned — all are best explained by appealing to the quality of the work, rather than any nefarious actions.

I agree there is a difference. But there are also other possibilities that I think complicate the situation. Many things are published. There is seldom if ever unanimity regarding the quality of the work. I’ve seen people I respect greatly and who are better philosophers that I am disagree profoundly about the quality of some paper, i.e., “how did that even get published in journal x?” vs “this is one of the best papers on this topic.”

Now let’s make that disagreement public and put it on social media and make the topic one that’s extremely morally or politically or socially sensitive. It will often be quite easy to start a pile-on, and it will also be easy to raise questions of “quality” and to find others willing to agree that the work is subpar. This doesn’t require that anyone act cynically (though some will). And so of course in such cases it will feel quite natural to conclude that the best explanation for why this piece of work should not (or shouldn’t have) seen the light of day is that the quality was poor.

This indeed happens quite often (and from all corners of the political spectrum). I figure that in this case, the lack of quality was exceptional, and suspect that the editor was blindsided (again, I’m agnostic about whether this was due to a technical or procedural oversight) and reacted hastily.

Once again, this isn’t just a just-so story. It matches the evidence. And it explains why no such thing happens with other articles in the same journal that sparked similar (or even stronger) reactions on social media (e.g. a recent review on conservative work on puberty blockers in the same journal).

I suppose we’ll learn more, assuming Justin gets a response. Your hypothesis is certainly not outrageous or anything, but I don’t think mine is, either.

What review are you referring to? I’m aware of a couple papers on puberty blockers in the journal but neither is a review–just curious if I missed a paper (and I have no intention of discussing the substance here).

One thing that speaks against affirming your null hypothesisis that the author has published on abortion in much better journals: Ergo; PPQ; JAPA. That suggests their work on this topic is far from shoddy.

Is the author the protagonist in another Daily Nous story a few years ago, on how to publish fast and furious as a grad student? https://dailynous.com/2021/01/21/publishing-guide-graduate-students-guest-post/

That’s it! Thank you for pointing this out, I’ve been wrecking my brains since yesterday where I have heard the name before.

As others have pointed out, if the review process was above board, this ought to be published. If someone has issues with the content, write a response. Not that it matters, but FWIW, I’m not sympathetic to the content.

There’s also, of course, an issue with hyper prolific authors who are kind of one topic authors. In the case under consideration: Abortion bad, and then there’s 100 different angles in 100 different paper submissions reaching invariably the same predictable conclusion. It’s for Editors to decide how they respond to that sort of thing, but surely not post acceptance notification, and surely not post peer review. My own view on this has always been to give such content some runway and then end accommodating such text production. You had your say, it’s time to move on to other content looking to get published.

But, Udo, surely editors should not follow the recommendations of reviewers blindly. If someone else finds severe problems with the paper (such as it being racist, sexist etc) – before it is actually published – then the right decision is not to publish the paper. Of course, what is sexist or racist can be contested, especially in philosophy, but my point is that it is not unreasonable that the journal will not publish this paper, since important problems of the paper has been brought to public before the paper was published. The mistake the author made (in addition to writing a bad paper, arguably) was to upload preprint to Philpapers before the paper was published. I am sure this paper would not have been retracted because of the complaints even though now it might not be published because of the complaints.

I’m sure what happened is a dream-come-true for the author. Instead of his umpteenth publication on abortion he gets a scandal and can present himself as the lonely fighter against evil wokeness…

Here is an analogy. A good principle about a conflict of interest is that you should not even put yourself in a situation where it looks like you have a conflict of interest. For example, you should not accept expensive gifts from your students. Even if you know in your heart that, as you relax in the luxury spa that they paid for, you are grading their papers fairly, it still looks like they are bribing you.

Likewise, even if the journal has good reasons for putting this article on hold, it still looks like they are censoring it for political reasons. It would be good to put policies in place that prevent this from happening again.

I’d apply the same principle to the author, too. He and his defenders keep saying, if you really read the text of the paper, you’ll see that this is a satire, and not racist at all.

The thing is, if one reads the title and abstract of the paper alone (which is what most people do when deciding whether to read further), it sure LOOKS racist and sexist. I can’t imagine why someone would want to post a paper whose abstract could so easily be interpreted as racist and sexist by other professional bioethicists, let alone interested members of the public. I also can’t imagine why a paper with a wildly misleading title and abstract was accepted as is, even by a guest editor.

I’m not disagreeing about the journal, by the way.

Thanks for shedding more light on this, Justin. Not only has no one offered a plausible reason for putting the paper on hold; no one has explained what’s wrong with the argument. I say this as a pro-choicer. People have failed to read the article, or lacked a sense of humour, but those are different things.

If anyone’s interested, I discuss the Hendricks saga at length—and also offer objections to his argument—here: https://open.substack.com/pub/wollenblog/p/the-braindead-war-on-perry-hendricks?r=2248ub&utm_medium=ios

The putative explanation for why this is business as usual confirms that it’s discriminatory.

“I can confirm that the article ‘Abortion restrictions are good for black women’ was put on hold after several complaints were raised. This is standard procedure for articles that are not yet published.”

The telling words here are “after several complaints were raised.”

That suggests that publication would be expected but for the complaints (otherwise, why mention the complaints? Why respond on social media?). The email to Hendricks fails to mention any further hurdle that needs to be cleared. That suggests that if there was a further step, it was a rubber stamp not ordinarily worth alerting presumptive authors who have made it this far. Also the phrase “put on hold” suggests an intervention in the ordinary course of events.

How often are complaints raised? Presumably, that doesn’t happen routinely. It’s more likely to happen when the topic is political. How often are complaints raised to journals about forthcoming papers on dry topics, e.g., some strategy for dealing with the Frege-Geach problem? I assume not often. If there’s a case where a paper on anything non-political has been put on hold because someone complained about it, and it’s not a matter of plagiarism or research fraud or something like that, I’d be interested to hear about what it is.

It also seems likely that the complaints must come from people the publisher deems credible. If Libs of TikTok objected to a forthcoming paper on political grounds, I would guess that would be ignored, and rightly so. Who are the credible people? Academics. Academics ooze credibility.

So in practice, this “standard procedure” of putting papers on hold following complaints seems only to be relevant when academics complain about forthcoming papers espousing political views they don’t like. So in practice, it only applies in a narrow range of cases. So it’s not very standard, is it?

My guess is that the “standard procedure” is mainly about allegations of data impropriety in quantitative sciences. T&F is an enormous publisher, the majority of whose journals have nothing to do with philosophy — or with anything political at all. The typical case where this “standard procedure” gets invoked is most likely when someone alleges (after acceptance but before publication) that data has been fabricated or a statistical analysis done seriously improperly. In cases like that it does make sense to put the paper on hold until there’s time to investigate.

It’s tricky to know how to apply data-checking procedures to philosophy. What is our “data”?

And these days, most allegations of data impropriety do seem to first appear on blogs or Twitter. There’s a pipeline from these allegations to publishers’ quality control offices. Social media flack about this article almost certainly went into that pipeline, where some decision-maker who usually deals with (comparatively) simple questions of data integrity now had to decide whether this qualifies — and not surprisingly punted it into the “standard procedure” to stall or make it someone else’s responsibility.

If there’s an issue of political bias here, I suspect it’s to do with social media rather than the publisher. The question is how allegations of research misconduct gather enough attention on Twitter to make it into the publisher’s anxiety pipeline. There’s some threshold below which they just won’t notice. You’re probably correct that this is more likely to happen with left-coded concerns than right-coded concerns. But that’s probably just because social media tends to lean leftward (though this has started changing on Twitter!).

TLDR: there is a simpler explanation for what happened here, which needs to be ruled out before conjecturing political bias at the publisher

No “research misconduct” is even being alleged here, unless having the wrong views constitutes misconduct. What am I missing?

I agree that there’s no evidence for anything that I would consider research misconduct. (I think this is an argumentatively weak paper that should not have survived peer review, but that’s not research misconduct, nor grounds for retracting the paper after acceptance.)

But the hypothesis I offered doesn’t require that there is research misconduct or even that anyone at T&F thinks there is.

The hypothesis is that T&F has a misconduct-detector heuristic that reacts to buzz on social media wherein lots of PhDs are saying that a piece should not have been published or should be retracted.

My guess is that this is a pretty reliable heuristic. It probably catches allegations of data misconduct somewhat often, and probably has few false positives. But there will be some false positives, because it’s a heuristic.

Ok, thank you for clarifying. I think that’s a terrible heuristic. If a lot of people on social media are alleging research misconduct, then ok maybe. But if they’re just saying stuff like “I just can’t” then no that shouldn’t change anything.

And I’ll add that the “heurstic” you’re describing doesn’t strike me as an alternative hypothesis that needs to be ruled out. It sounds pretty much like precisely what I’m assuming happened only that you’re less alarmed about it than I am. This hypothesis just is a description of how political bias would be implemented in practice.

No, these are different hypotheses.

You speculated about a political bias *within* the journal/publisher.

I suggested a simpler explanation: the journal/publisher employs a relatively unbiased heuristic that takes input from a different system, social media, which has its own (documented, not merely hypothesized) political bias.

The difference is whether we postulate new (unevidenced) sources of bias: your explanation does that, mine does not. In general, it’s best to treat as default the hypothesis that does not postulate new entities or causal factors, at least until there’s evidence unexplained by the default.

Interestingly, you’re currently arguing that the intentions of the journal/publisher don’t matter, since bias isn’t about intentions — it’s about systemic effects. That approach certainly has precedent.

Ok, I see what you mean about the different hypotheses. That leaves us with a substantive disagreement.

“An unevidenced source of bias.” Really? So, in theory, we should expect the publisher to put a paper on hold because some right-wing academic said things like “I just can’t” on X.com about the preprint of a woke paper. The only reason this isn’t more likely to happen has to do with the lack of presence of right-wing academics on that site. It’s as though nothing like this has ever happened before, and we have no prior experience that might suggest that academic publishers might be more sensitive to left-wing pressure than to right-wing pressure (not just that the former is more likely to materialize). I think we know that’s false.

In any event, since you would, I take it, adopt some variant of the systematic outcomes account of bias, I’m not sure what difference this distinction makes for you.

Do you honest to God think that this is the implementation of any preconceived policy, as opposed to an ad hoc response to social media pressure (that feels forceful because it’s coming from within the political in-group)? Why haven’t they mentioned this policy?

If this is satire, then it’s bad satire. Section 2 is where Hendricks supposedly shows that it’s “commonplace” for “authors” to claim that abortion restrictions hurt black women without arguing that abortion is wrong.

In that section, he cites one bioethicists who supposedly does this. (I’m skeptical, but grant it for the sake of argument.) He then says it happens a lot in news media and cites three articles of this genre that he says do it.

But for his satire to work, it has to be the case not just that “authors” commonly assume that abortion is permissible in arguments that abortion restrictions hurt black women, but also that bioethicists commonly do so. Popular newspapers, magazines, and websites often have very low standards for arguments. If he wanted to make a point about these low standards by intentionally settling for them, then he should have submitted his paper to one of them. If he wanted to satirize academic bioethics for settling for standards that his article meets, then he needed should have shown that academic bioethics settles for those standards. Citing one article isn’t enough.

(It seems really bad to me that the journal seems to be changing course in response to reactions on social media.)

At least if the paper is pulled, the author cannot complain. The argument seems to clearly exemplify an epistemic vice (a few, in fact), and it is certainly good for people, regardless of their race or gender, to be prevented from being intellectually vicious in public.

I clearly lack the epistemic (and moral) virtues that many others here have. Therefore, I must defer to their expertise in arguing that we ought to make room for it. In that Modest attitude, I make the following Proposal.

Since it is imperative even for philosophers’ own good that they be prevented from being intellectually vicious in public, but many of us — including, apparently, a number of people who serve as journal editors — lack the discernment to recognize when articles like this one manifest epistemic vices, we ought to do away with journal editors entirely and replace them with a central committee of virtuous philosophers who can accurately tell the journal publishers what it is acceptable to print. Since the aims of this committee would be to prevent public harm not only to the vicious philosophers but also to all the countless millions who read philosophy journals, I propose that this committee be named the Committee of Public Safety.

The question then arises: who is qualified to serve on the Committee? Only people of unquestionable virtue and impeccable judgment, with the moral and epistemic vision needed to discern truth and goodness where many of us are short-sighted or plagued with uncertainty. Clearly, the job calls for dogmatism and confidence rather than self-doubt. I therefore propose that those who have engaged in quibbling here and elsewhere should be disqualified automatically, and that those who have a proven track record of early and unqualified denunciations of the vicious among us make up the whole of the Committee.

Unfortunately, since this comment of mine is not a philosophical journal article, it does not come with an abstract in which I can be expected to make clear whether I am speaking sincerely or engaging in satire, using a reductio ad absurdum, or presenting an argument so that people might consider where it leads. Apparently, this will make it next to impossible for the sorts of people who might serve on the Committee to figure out what is going on. Pity!

I find it amusing to see the juxtaposition of comments like this and comments expressing skepticism about whether ideological discrimination against conservatives (and others) is happening on a scale we need to worry about.

It reminds me of a joke I heard when I was a child.

Lucy says, “Mildred, this dish you recently returned to me has a big crack in it now!”

Mildred replies, “Well, first of all, that dish was in perfect condition when I gave it back to you. Second, the crack was already there when you lent it to me. And third, I never even borrowed your lousy dish!”