“Incompetence”, “Arrogance”, “Misunderstanding”

Last month we had a very active post with readers submitting their “Philosophy Journal Horror Stories.” The following story, recounted by Nathan Salmon (UCSB), fits well with that collection.

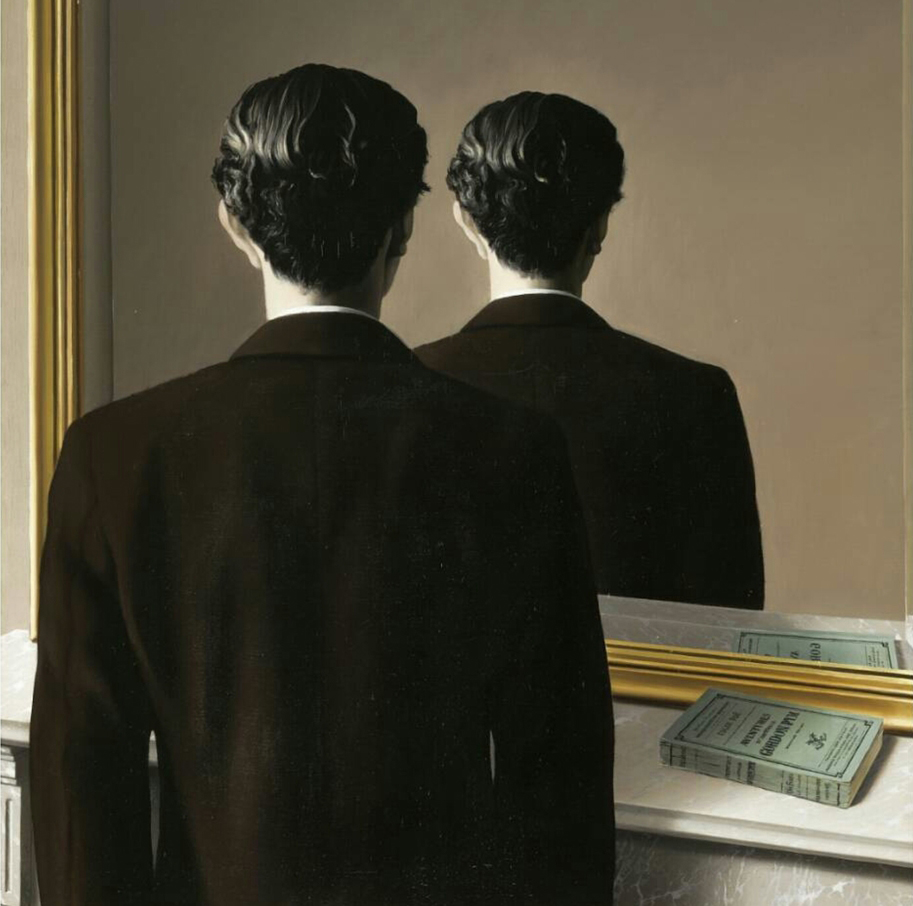

[René Magritte – “Not To Be Reproduced”]

I received an anonymous referee report that emphatically rejected my classification of a particular contemporary philosopher as one among several who do not endorse certain views that have been attributed to them by some careless readers. The referee authoritatively declared—without a shred of textual support, yet without a trace of tentativeness—that the philosopher in question very definitely holds the views in question. So confident is the referee in fact that they declared my interpretation to be disingenuous—either that or naïve.

The contemporary philosopher whose views are in dispute: Nathan Salmon. I had referred to myself in the third person for the purpose of blind review.

Because of the sheer volume of submissions in analytic philosophy, any referee for a journal submission is effectively given unilateral veto power over that submission, under the full protection of professional anonymity. In my experience, the current dysfunction in the peer-review system in analytic philosophy is due in large measure, but not entirely, to simple professional incompetence, often combined with arrogance. It is also due largely to widespread serious misunderstanding of the reviewer’s assigned task, which is not to declare whether the work under review has persuaded the reviewer to relinquish their prior theoretical stance, but to make a professional assessment with regard to merit and suitability. There is also the unfortunate tendency among some to troll, especially if that can be done anonymously. Worst of all, the dysfunction is also due partly to professional abuse of the veto power for the purpose of suppression, to protect the reviewer against published criticism or to influence the narrative in the reviewer’s favor.

The system of peer review in analytic philosophy is badly broken and needs to be re-imagined.

Suggestions for such re-imagining welcome. Or perhaps we should abolish pre-publication peer review?

I feel like to fully evaluate this post week need to know what the view in question was. What if Nathan is mistaken about what his published work actually argues for? I am 85 percent joking.

I am not a philosopher. I find this disturbing. On the one hand, I thought I believed in the concept of peer review, but not in cancel culture. If a work is “garbage”, I would hope most/all reviewers would readily agree. If it is well written and well researched, and controversial, that should readily be approved and there ought be no one-reviewer veto unless s/he can convince others it is “garbage”—badly written and/or badly researched.

Just my 2 cents.

I am somewhat skeptical of the benefits of double-anonymous review; this is one of the reasons.

Could it be that Salmon’s published work lends itself to the reading of Salmon to which the reviewer is referring? Maybe Salmon is wrong about Salmon. One can’t know without knowing what textual commitments are in question.

What about a system where authors rate reviewers and then these reviewer ratings go into a database that all journal editors have access to before choosing reviewers? There are a lot of incompetent reviewers, but still only about 1 in 4 (in my experience). This simple system could weed them out.

While this idea has potential, I worry that the results would basically be the same as the result of student course evaluations – namely reviewers who recommend publications will receive high scores, while reviewers who recommend rejection will receive lower reviews…

The temptation to hate on “Reviewer 2” will often be too great to pass up.

I worry about that too. Editors should (and many do, internally) rate referees though.

It is curious that the editors in this case didn’t catch that the reviewers were rejecting the author’s assessment of their own previous work and perhaps taking this into consideration in their editorial decision. While some journals triple blind reviews, this is a good example of why that is a problem.

Not curious at all as many journals are triple anonymous.

Maybe that’s a bad idea too.

Could be but I don’t have a hypothesis as to why. And I do think that before anonymity fancy people had an undeserved leg up. And uncertainty about fanciness leads to more care in refereeing the unknown/non-fancy. But, as I say below, I don’t think all journals should be run like all the rest.

Even if there were three anonymous reviewers, as opposed to two, and the vote was 2 to 1 against acceptance, the editors in their discretion could have decided in favor of publication, no? At least in theory, peer reviews are supposed to be advisory, not dispositive, at least that’s my impression, and one might hope that in cases of fairly sharp disagreement among reviewers the editors would look at the paper for themselves. I realize that may not be how things work in practice most of the time.

Or am I mistaken and does “triple anonymous” refer to the editors not knowing the identity of the author of the submitted paper? (I guess that would make more sense in the context of the exchange above.)

Yes.

Depends on the journal. I believe some have a policy of just going with the reviews. Phil Imprint comes to mind but 3 reviewers are rare.

The relevant journal does use triple-blind refereeing. In fact, the journal invited my co-author to referee the submission.

That is the most obvious worry, but, to alleviate it somewhat, I often find myself praising referees who recommended rejection of my paper (and vice versa). On the other hand, to the extent that referees are keen to receive positive reviews from authors, they might being to recommend publication more often, which in itself might be troublesome.

To infer that “the system of peer review in analytic philosophy is badly broken and needs to be re-imagined” based on some (even numerous) instances in which a peer reviewer has badly failed in their duties is a little like inferring that the global climate isn’t getting warmer based on some extreme cold weather conditions in one’s particular locality. If you want to infer something about the global climate, then you need to cite facts about the global climate, not facts about your local weather. Likewise, if you want to infer something about the peer-review system, then you need to cite facts about that system, not facts about your own particular experience with certain peer-reviewers. Thus, if Professor Salmon had shown that, under our current system, you can’t get good papers published, then he would have provided some good evidence for the system being broken. But, as it is, Professor Salmon hasn’t said whether he’s found it impossible for him to publish a paper where he sets the record straight on how the careful reader should interpret his work. I wish people would stop saying that our system is broken without giving any evidence that the system is failing to weed out unpublishable papers while more-or-less ensuring both that good papers are published and that better papers are published in more prestigious journals. In any case, I think that we should think of our peer-review system as Churchill thought of democracy. It’s perhaps the worst system for deciding what to publish except for all those other systems that have been tried from time to time.

Except we don’t have other models to compare it to. We don’t have any data about how well or badly it works (which is, I think, evidence that it doesn’t work). And we don’t have any data about how it’s getting better or getting worse. It’s an entirely unregulated, unguided, unmonitored system.

How is the absence of evidence evidence?

Generally if something works, there’s evidence that it works.

What form would this hypothetical evidence take?

That’s an excellent question. Our problem is we don’t know what our goals are here or how we would measure success in meeting them.

The analogy here is wildly prejudicial and not really apt. A better analogy to what Salmon describes would be cases of medical malpractice like say where a doctor amputates the wrong leg or makes a misdiagnosis that causes a patient pain and suffering. You couldn’t ignore cases like that by simply saying “Well show me a better system!” In both Steinhart and Salmon’s examples a referee recommended rejection on the basis of a factual misunderstanding based on their own incompetence. If that’s not malpractice what is? And the only proper response to something like that is to ask what we can do to minimize if not eliminate such cases of egregious malpractice. Also, it’s just utterly bizarre to say that the only thing that would prove failure of the system is allowing bad work to be published. Why in the world isn’t rejecting good work also a failure of the system? Presumably the system is supposed to reach truth or something like that, which is a different matter than avoiding falsehood. If I gave all of my students F’s then I’d completely avoid the problem of unfairly rewarding B level work with A’s or C level work with B’s. I’d also rightly get in serious trouble since giving a student who deserves an A an F is at least as serious a bit of pedagogical malpractice (if not a far worse one) than giving a student an A for B level work.

Sorry I’d meant the previous comment as a response to Portmore. I hope that’s clear from context.

Maybe one way to defend Douglas’ position on lack of evidence of the peer review system failing, by way of falsifying your conditional, is that “work” may attain application conditions that can only be adjudicated on in relation to what we observe regarding outcomes of alternative systems, meaning that something could work without evidence thereof if there is nothing to compare it to. This would be because this evidence in question is relational in nature.

Of course, one might reasonably assert that such relational evidence could obtain if we compare what we have currently to IMAGINED outcomes that intuitively seem attainable and claim that the current system does not work in that way.

Just some thoughts.

Actually, Eric we do have various models within “our” way of doing things since journals are by no means monolithic in how they do things. I do think some things are broke – there is too much work to go around and no good way to stem the flow of submissions in a way that is both fair and doesn’t keep good work out. But we have some experience with different levels of anonymous review. And also some experience with different journals that are run in different ways. And over time there seems to be more care in some journals about such issues. We obviously have not tried every way of doing things, but there is a range. And we don’t have representative data sampling. But we also don’t have no evidence.

Sure, all good points, but it sounds like variations on the standard publishing model. I’d like to see new models.

I think that would be good too.

Pointing to systemic flaws is exactly what Salmon does in the third paragraph (e.g. referee’s veto power combined with bad faith/incompetence behind the veil of anonymity). But even it weren’t enough to show that the system is broken (I for one don’t think it is), it’s not clear to me that Salmon is making the inference you’re attributing to him. He’s recounting a bad experience, suggesting he’s had or heard of a fair number of other bad experiences and also saying the system is broken. The system being broken, for a number of reasons besides those he lists, leads to such outcomes. But I’m not sure he’s concluding that the system is broken simply based on his own experience. For that reason the climate/weather analogy doesn’t quite work. But then Salmon’s actual views are clearly open to interpretation so I might be wrong! 😄

But referees don’t have veto power at most journals. Editors make the decisions often get multiple opinions, and can ask for further reviews if they think one is needed. Sure,they too can and do make bad calls. But any system of refereeing will have bad calls at some level.

Surely Salmon intends ‘veto power’ to be understood de facto, which referees indubitably have

They most definitely have de facto veto power in many cases. Many journals are perfectly honest about the fact that two glowing reports are required for getting an R and R (examples include AJP and Ergo).

So if you write a negative report, you typically know that this will sink the chances of the paper being published in this venue.

I’m sure rare exceptions occur.

My thanks to Norwal. I wrote ‘*effectively* given unilateral veto power’.

I agree with you in that I’ve seen editors supersede positive reports, as is their prerogative. I was engaged in exegesis of what Salmon was saying, not stating my own view. But it remains true that without two positive reports at many places it’s near impossible to get anything through the door, which suggests a de facto veto power (exercised by proxy through the editor).

FWIW, it goes both ways, though since journal space is limited it tends to go more one way than the other.

Here is a possible alternative to the current system: Instead of asking two reviewers evaluate a single paper, we could ask a team of five experts on topic x jointly evaluate twenty submissions on topic x and select the best two or three papers. The team gives extensive feedback on the best papers (but not on the others) and the editor makes the final selection. This method resembles how grant proposals are evaluated. I am not claiming that my alternative is perfect, just that it could be worth testing.

I’m an expert on topic X. I have publicly funded research projects going on, postdocs, a full teaching load, graduate students, two small children. I don’t really have the time to read 20 papers for review.

When I reviewed grant proposals, I only reviewed them one at the time.

5 reviewers / 20 papers is less than 2 reviewers / 1 paper. The total number of hours spent on reviewing would decrease (which I guess is desirable).

How does your proposal work exactly?

After the first post, I thought it was that the five experts are each reviewing each of the 20 papers, which would be more total work than if each of those papers were sent to one reviewer.

Here is how my proposal works: The five reviewers together identify the two or three papers they consider to be best, but they do not have to carefully read and give feedback on all 20 papers. If the task is to identify the best papers in a set of 20, it will in many cases not be necessary to carefully read all papers. It will often be obvious that paper x is not as good as paper y even if you haven’t read the papers carefully. An advantage of this proposal is that each reviewer will have less influence over each paper; it is less likely that any single reviewer will be given veto power over a paper.

An idea:

Single blind, double review system:

1st review is blind.

2nd review is fully transparent review of the first review (not the paper) with both author and reviewer’s name known, to identify whether that recommendation should stand or fall based on the kinds of issues brought up in the post, above.

More narrowly, we could dedicate this second reviewer (or a third) to only look at a very small set of potential review problems.

We’d need a special name for this second (or third) reviewer. I suggest calling them the ‘editor’.

But Matt’s proposal has the advantage that it is not a single person (with their particular views about what constitutes good philosophy, etc.) that makes these decisions.

Anonymous peer-review is the best of several bad options. Many reviewers do an excellent job but some are woeful in their incompetence and unprofessionalism. Anecdotally, I have also seen a rise in “trolling” reviews. Furthermore, editors generally fail to adequately police these bad practices (perhaps because they are overworked with little or no remuneration and struggling to deal with ever increasing submission rates).

The solution seems to be tweaking the system to incentivize better reviewing (or disincentivize incompetent and unprofessional reviewing). The question is how to effectively do this. I think collectively we need to put a lot more effort into thinking through this and evaluating various proposals.

One idea I like is journal’s giving awards each year for the top 5 or 10 reviewers. This could be based on timeliness, thoroughness, and helpfulness. It could be as easy as Associate Editors having a box they can tick when they receive a referee report to shortlist it for this award. At the end of each year, editors from the journal could then review the shortlisted reviewers and choose the best ones for awards. Of course, this is no silver bullet, but presumably it would have a modest effect on report quality as many would like to have such an award listed on their CV.

Another idea is creating a better system for recording each individual’s record of reviewing. This is much harder to do. But imagine if every scholar had a publicly accessible record of how many articles they had reviewed, and how many reviewer requests they had turned down. Even better would be if editors had a box they click if they decide that a review is too incompetent or unprofessional to be used. This could also be included in the public record and thus someone who trolls might find their professional reputation diminished by the high number of ticks in this third box in their public record. (Also, editors might be more incentivized when they know that taking action against an incompetent or unprofessional review will have a broader impact beyond the single article under review).

Further ideas are: (1) having some kind of inter-journal flagging system for recording strikes against reviewers who are grossly incompetent or unprofessional, which professional consequences for too many strikes such as submission embargos; (2) getting universities to put greater emphasis on reviewing as an essential component of service expectations (which would help address the shortfall of reviewers and thus make it easier for journals to find quality reviewers); and (3) have an author and editor rating system that allows editors to see the average rating of each potential reviewer whose name comes up in the system.

This is just a start off the top of my head. If our profession put more effort into fixing this problem, I’m sure that we could come up with some practical proposals that are likely to work and make some kind of a difference.

I was publicly shortlisted for an award like this a couple of years ago. It was nice.

It never occurred to me that it would be even slightly helpful for my CV.

One of the major problems in philosophy is that on any given topic philosophers can have radically different starting premises. If your journal submission goes to a referee with radically different starting premises, you’re pretty much screwed. Granted, in your specific sub-(sub-)field people are more likely to share many starting points, but it can still be a gamble. Sometimes your submission is sent to someone in an adjacent sub-field, and then they’re much more likely not to share starting premises. I don’t think such issues can be solved by changing the implementation of the peer review system.

I think this is too pessimistic.

From a recent referee report I wrote:

I have some fairly severe disagreements with many parts of the paper, including [redacted]. But these disagreements are way out of the legitimate space for referee criticism, and way into the ‘disagree-in-print’ space.

I see referee reports like this often.

Other people are almost as wonderful as I am.

Almost.

In seriousness, I don’t think I’m particularly unusual in saying things like that (and Mark van Roojen’s testimony supports this). Lots of people have a good and professional attitude to refereeing.

I am still dreaming of someday getting a referee report like this. The reports I get are almost always of the “this is stupid and wrong and probably not even philosophy” variety. Frequently, the reports look like, “Write this other completely different paper that I would have preferred to have read.”

FWIW, I think that too many of us suppose that all journals work the same way, and also that one way is best. I tend to think it is a good thing that journals don’t all adopt a single “best” system, though I tend to favor anonymous reviewing over reviews in which the authors and editors know who wrote what is under review. Still I would not advocate completely abolishing the alternative since it is good to have alternatives.

Daily Nous readers are encouraged to look at the discussion of the case on my Facebook page. (It is a public post.) Some readers have suggested that perhaps this is simply a point on which my writings are easily misinterpreted. This is not a case of that sort. The particular misinterpretation in question is of several philosophers, none of whom is easily misinterpreted on this score. The referee singles out Saul Kripke and me by name. (I can be more specific about the misinterpretation if and when my submitted article, which is actually co-authored, is placed.)

Occurs to me that this is all fodder evidence for the old debate about privileged access. It did extend my mind on this.

If Prof. Salmon is right that the current dysfunction is due in large measure to simple professional incompetence, then that is tough to fix. I do think more training in how to referee (where and when I don’t know – perhaps in graduate school) would help mitigate the second issue of widespread misunderstanding of the referee’s task.

But really I wanted to offer the throwaway thought that this came up on some social media site, and someone suggested having paid reviewers at journals, as a full-time job. If a journal had, say, two or three posts available, paid at postdoc wages, then we might have highly competent reviewers handling 300-600 submissions per year, with much quicker turnaround. It’s fun to imagine the knock-on effects on journal prestige and other aspects of the system.

Totally unrealistic, I know (big publishers need those profit margins), even as a lot – a lot – of money goes from universities to publishers, and from funders to publishers (by way of open access fees built into the grants).

Josh, an interesting suggestion, however this would de facto make these ‘full time referees’ (if their identities were revealed) the most powerful people in philosophy. They would hold everyone’s careers in their hands… and this could turn corrupt very quickly. Of course, they *could* be full time paid referees and just keep their identity as such secret (like CIA), however people could probably figure their identities out… after which desperate job seekers needing something in, e.g., Phil Studies will have every incentive to (like the Pharma people) send these reviewers steak dinners and for the Phil Review a Patek Phillipe or whatnot.

agreed, the full-time journal referees (when rolling up to the APA) would be treated (at least by everyone on the job market) with the reverence of a person evaluating hotels for the Five Diamond award …

Haha perks of the job! As I say, an unrealistic suggestion, though I actually doubt this would happen. At many journals the editorial staff plays a very important role in selecting reviewers, and in making the final decision about the paper – sometimes overruling referees – but I don’t think they get many steak dinners. But what do I know? Almost nothing.

I do imagine journal reputation would start to turn on the quality of the referee staff, in this possible world. Might even be a good way to get a fancy faculty job – a kind of alt postdoc.

I do think more training in how to referee (where and when I don’t know – perhaps in graduate school) would help mitigate the second issue of widespread misunderstanding of the referee’s task.

I would think it could make a decent assignment in a grad class – maybe in a proseminar, but maybe later – to have a professor give a draft paper to the grad students and have them write referee reports, and then to share actual referee reports, for that same paper or others, to compare them and talk about what makes them good or bad. Maybe people already do this.

I don’t think you could find people – especially at the postdoc level! – with sufficiently broad expertise, given that papers are supposed to be refereed by people highly informed about the particular topic of the paper. (e.g. I’m competent to review most work in philosophy of physics, but by no means all of it, and I have unusually wide research interests and have been research-active for 20 years.)

Egregious mistakes of interpretation of the author’s paper are going to happen in peer review. Unfair rejections are also going to happen in peer review. These are things we should simply accept, I think. (We might not like them, but we should accept them.) What is unacceptable — and has to be fixed — is the wait times. That is the real issue. I am tenured. So, it doesn’t bother me much. But, dear God, when I didn’t have a tenure-track job and when I was on the tenure track, I can’t tell you how frustrating it was to wait for decisions that took well over a year. This is devastating for people without tenure. We have a system where you have to go one by one with papers. So you’re completely at the mercy of the journal. It’s a totally one-sided system, and the wait times have to change. I know I haven’t proposed any solution; I’ve merely complained. But at least I’ve isolated what really needs to be fixed.

Here’s one potential idea for helping with the backlog that connects to recent discussions in the philosophy blogosphere: count public philosophy toward our assessments of job candidates / tenure / promotion. Instead of increasing trying to increase the number of journals or hiring paid reviewers (the latter I fear would be like adding another lane to an already congested highway), we can instead give people more options about how to advance their careers.

How this is carried out is probably best addressed at the hyper-local / departmental level (I can imagine R1s taking a very different approach than a SLAC or an R2 or a CC) but the downstream effects of such a proposal could make significant improvement on the timeline problem. If someone can get tenure with three articles and a well-liked Youtube channel full of philosophy (or a series of local / national talks, think pieces, INSERT YOUR PREFERRED CRITERIA HERE), then the pressure to achieve professional distinction via the journal system will lessen.

Eric Schwitzgebel’s proposal for how this might work at a place like UCR (https://dailynous.com/2021/01/13/departments-credit-faculty-public-philosophy/) is an excellent starting point for this kind of discussion.

The difference between medical and reviewer malpractice is that there is quite often a pretty clear standard for such things as botched surgery. That’s just not the case with respect to philosophy papers or books.

I remember how indignant I was when, many years ago, my first submission to a publisher was criticized for such things as spelling the name of the person I was writing about exactly the way she did. (In fact, the specific complaint regarded my multiple “mispellings.”) I can’t say now whether that paper was any good or should have been published, but, clearly, simple factual errors like how a name is spelled (or the one described by Prof. Salmon in the OP here) ought not to be the principal reason for the rejection of any article.

Unfortunately, philosophy journal declines are not generally based those sorts of undeniable mistakes, but on philosophical disagreements. And, given the huge volume of offerings, there must be SOMETHING to use as a filter. Philosophy. being what it is, this is not a problem that can ever be fixed–say, by reviewing reviewers. It will always be the case that many “great papers” (like many “towering works of fiction”) receive multiple rejections, while many “terrible papers” (and “garbage novels”) are quickly accepted. There’s just no help for it.

I am going to reiterate some things I said on Nathan Salmon’s Facebook post:

1) One thing that this review horror story makes clear is that some of the desired virtues of peer review were operative in this case. I am not saying it was a good review (I haven’t read the review or the manuscript, so I don’t have much judgment there; it sounds like there were some obvious issues). But, presumably the person writing the review was, in fact, unaware that the author of the paper was Nathan Salmon. That’s…a good thing! I know it is frustrating to have one’s work misread (and it seems that people are very eager to pay attention to this frustration when it happens to a prominent and well-established senior figure, though, of course, most of us have dealt with equally silly referee reports without getting this level of attention), but insofar as anonymous review is something that we think is valuable, and insofar as we expect that sometimes reviewers will be wrong about things or that there will be careless or haphazard reviews and reviewers (why on earth would that happen, we might ask?), there are bound to be such cases.

2) Nathan Salmon is a very well established philosopher with a hale and hearty CV. If he wants to publish his work, he could easily get it published without going through whatever journal he was seeking to get it published in here. Maybe he finds that seeking publication in journals usually helps improve his papers? (His FB post suggests otherwise given the vitriol about the peer review system, but I don’t know).

Of all the people harmed by capricious reviews, he is surely not the one with the most to lose. We might think then that he is to be lauded for speaking truth to power, but I actually think this is not quite right since one of the largest issues with the system is that it is overloaded with submissions, and vastly underloaded by people doing the editorial and referee labor, and signaling to the profession that such labor is, in fact, prestigious and valuable. I don’t know how much refereeing he does. We pretty much don’t know how much refereeing anyone does. But we know how much publishing people do. Because that’s what we treat as the prestigious and valuable contribution to scholarship in the profession.

3) The people who are best situated to actually take steps to fix things, to reform things, and to reimagine the journal system to their liking, are the people who are not under publication pressure in order to secure or maintain their employment. That is: people—like Nathan Salmon (though not just him, obviously)—who are already in secure positions with ample prestige, who can do things (apart from just posting about their bad experiences or “starting conversations”, like, starting a journal that runs things differently, or submitting to journals that run things the way they want, or spending their time refereeing, editing, etc., or whatever it is they think will actually fix the journal system, rather than simply complaining that the person who refereed their paper did a bad job (oh, also: if you are at a place with a grad program: make sure your program is explicitly training grad students how to write referee reports).

I’ll just close by noting that I see many people on this thread debating the best entire alternate systems. But we’re not going to schedule a vote as a profession and pick a different journal system. We are going to each make choices individually about what to do when we send papers places or if we are editors of journals make choices about journal policy. This is why I say: the people with the most ability to impact change are the one’s with the most career security (or maybe I should say the ones with the least concern about career security). They can start journals with new and innovative policies, or submit to journals without as much fear about prestige costs. They can write letters of recommendation that get taken seriously because of their stature (and begin to change what the contents of those letters speak to).

I understand how pressing the issue of work overload in peer reviewing is, given how much it affects a larger class of people in a very unprivileged position. But that is not a reason to dismiss Professor Salmon’s concern, since both his concern and yours merit discussion, and doing so is not incompatible. As I understand it, his concern is that current blind-review system(s) gives undue veto power to anonymous reviewers, allowing them to reject papers based on their disagreement with them rather than on their merit, which in turn contribute to pushing for, or maintaining, certain philosophical narratives over others (whether intentionally or not), depending on the prejudices of the referees. If the concern is justified (I largely agree that it is), it points to a systemic problem prone to privilege certain ideas (arguments, etc.) as more publish-worthy if they are in line with current orthodoxies (whether justifiably or not), and which affects us all (if someone as renowned as professor Salmon is affected, it is reasonable to expect that less renown people would be affected more seriously).

I would also add that having a philosophical reputation already made, and job security, does not give someone the necessary influence to make a significant change towards the systems currently operating (whether with respect to practices regarding work security or academic integrity). In my opinion, some renown and very competent philosophers, largely viewed as “fringe” figures, and have very little power to influence on the current them (whether this is the case of professor Salmon, I do not know). However, having public discussion of these issues has the potential of bringing more attention to them, and maybe be in a position to have enough combined influence to make significant changes, which is sufficient justification to have those discussions.

I am grateful to Mel for her/his thoughtful remarks. As a member of the editorial boards of philosophy journals, I have in fact made a number of appeals to journal editors-in-chief to reconsider some of their journals’ inappropriate practices–such practices as relying on a referee report that the editors know was originally written for another journal, and such as seeking an assessment from the very philosopher targeted in a critical submission, often the single least appropriate potential referee on planet Earth. Scholars in other disciplines have assured me that these same practices–which routinely occur in analytic philosophy–are prohibited in their disciplines. On the basis of my experience I can testify that it is going to take a lot more than my voice to effect the kind of systemic change that is badly needed in our peer-review system as it presently is. Generally, the most competent potential referees don’t particularly want the task, for very good reason, and too often those who do want the task want it for exactly the wrong reasons. The bottom line is that peer-review in analytic philosophy ultimately depends on most philosophers making serious efforts to conduct themselves professionally responsibly.

Nathan, I am not suggesting that you can change the course of an entire system by yourself, and I don’t think that’s what my comment suggests.

I also think that there are issues with how editors conduct the solicitation and evaluation of referee reports (see the post I linked in my original comment and on your FB page on how to impose on people better, where I take editors to task for not outlining what they even want in a referee report, and graduate programs for not generally training people on how to write referee reports).

My point is that since we do not have a deliberative body which can call the question, and we are not going to table the debate and overhaul the journal system en masse, a discussion dominated by people proposing radical overhauls of the journal system is a misguided discussion which doesn’t bring us closer to the changes you are suggesting we need and which seem necessary and have been identified by people as necessary in many prior discussions.

It seems relatively indisputable to me that:

1) with respect to social norms in the profession, the people who are more prestigious and influential have the greatest impact on how those norms can change and evolve.

2) with respect to freedom to explore and experiment with alternate approaches to journal arrangements and publication schemas, people with the greatest job security and least publication pressure are in the best position (perhaps alongside those with nothing to lose).

The combination of (1) and (2) suggests that people, like you Nathan, who are in that intersection of (1) and (2), should just be experimenting with different approaches to see what works best and expending your social capital to reward people for doing better by way of good refereeing and such (or nudging people towards the norms you want to be in place). That doesn’t mean you can single-handedly fix the system, it just means, don’t expect that the solution is to convene a grand discussion of what the correct end-state looks like, reach consensus and then we arrive a it; just apply what pressure you can towards where you want it to go.

Importantly though, the pressure doesn’t just get applied through speech, but through action like when people see Big Names publishing in journals they don’t expect, or they see Prestigious People taking refereeing seriously and taking the time to teach grad students how to do it right, etc. (maybe you do this, I don’t know; it’s something the profession as a whole *doesn’t* treat as nearly as valuable as it should).

Just throwing this out as an idea that came to me in reading this thread. We have the technology these days to post a paper securely online so that it’s only accessible to editors, referees, and authors, and to preserve the anonymity of all relevant parties. Perhaps it would be worth referees and authors engaging pseudonymously in a discussion (a dialogue even!) about the merits and demerits of the author’s paper during a fixed time window. Nothing too involved — just marginal annotations that can be replied to, followed by a short summary paragraph by each referee and their verdict, which permits the author the ability to respond. After which the editor(s) can make a final judgement.

For referees acting in good faith, this could bring to their attention misreadings or uncharitable interpretations of an author’s view, and presumably it would benefit the author to learn of such misreadings. Having the oversight of someone (whether it’s an editor or a submissions manager) who knows the referees’ and author’s identities would mitigate the Gyges effect and other forms of perniciousness. It strikes me that such a process would displace the veto power of any one referee, and if it unfolded during a fixed timeframe it’s not obvious it would result in greater delays to the time it takes to conduct a typical peer review.

This would be a fairly large increase in the time commitment required of referees, I think. (I’ve just put aside this afternoon for refereeing; it’s a delineated window of time that I can use to focus on the job* and otherwise keep it away from other work tasks. It would be a lot more intrusive to feel that I’d have to schedule and engage with this dialog process.)

*other than occasional procrastination on DN

It will be an increase in the time commitment of referees for any individual reference request. With that said: (1) if it leads to fewer papers getting rejected for silly reasons, then it could well lead to fewer papers being resubmitted, and therefore an overall decrease in the amount of time spent refereeing; and (2) referees may well be happy to accept the additional commitment if it entails that they’re afforded the same opportunities—I know I would, ten times over!

(As a matter of personal policy I do not respond to trolling.)

We could improve journal publishing in lots of ways. Here are two ideas. (1) Emphasize *training* people to become good referees. (2) As part of that, change the general attitude of referees toward the work they read: Rather than being a gatekeeper, looking for reasons to reject, be a nurturer and help the work become the best it can be. (Good editors used to do that sort of work, I think, though few have the time these days.)

We also need many more journals, and/or journals should publish many more papers per year, so that acceptance rates can be significantly higher. It is much harder to publish in philosophy than in almost any science, which just isn’t reasonable.

I want to resist this conception of a referee’s duty. I’m not refereeing on behalf of the author; I’m refereeing on behalf of the journal. My graduate students are owed the best help I can give to improve their paper; the person I’m refereeing isn’t. The problem isn’t that referees are gatekeepers; the problem is that referees sometimes have an inappropriately demanding conception of what the conditions are to pass the gate.

I’m still catching up with the thread, but here’s one thing I haven’t seen come up after doing a search that deals with the *specific issue* of papers dealing with one’s own work. The topic has come up a few times at philcocoon, as people are understandably at a loss as to how to cite work that builds on previous work, because there is a dilemma: present it as work by [redacted] and you risk being easily identifiable; present it in the third person, and reviewers are likely to think the piece is too derivative (on your own work, as it turns out!).

How to fix this? Here’s a suggestion: I know, from good sources, that it’s fairly common for authors who submit to ‘Nature’ and ‘Science’ to appeal rejection decisions, appeals that often lead to acceptances in those journals. Now, for various reasons (some have come up) I don’t think these are the best models for philosophy journals. And, of course, I don’t advocate free rein on appeals (everyone would do it every time).

But there could be a strict list of grounds for appeals (none of which would be based on just the author’s assessment of the quality of reviews). Such a list could include as grounds for appeal the following condition:

-A significant part of a reviewer’s negative assessment could be corrected by revealing the author’s identity.

That might need tweaking, but something like this could address the issue Salmon complains of, and an issue that to judge from philcocoon, many authors struggle with. No doubt other conditions could be added, and I imagine in the long run the effect would be to unclog the system some, since papers accepted post-appeal would not make it back into the system.

Just a comment of the “training reviewers” variety, one way in which the journal’s expectation from reviewers might easily be conveyed is by providing a short checklist/questionnaire that the reviewer mus t submit along with a written review. I have come across a journal or two that does this and it seems to be a useful way in which to gain some relevant information about a paper’s merit that may not automatically be included in all reviews. A short list of questions that simply asks things like “is the paper well-argued/well-researched/well-written/properly referenced; does it make an original /worthwhile contribution”, etc. gives some guidance as to what the reveiwer should be looking out for. If all of these questions are answered in the affirmative and the recommendation is still a rejection, the reviewer has to work that much harder to justify their recommendation and clarify why it does not simply come down to their personal disagreement with the central thesis.

Nothing is going to change so long as the volume of submissions remains unmanageable. The volume of submissions will remain unmanageable so long as too many graduate students are trying to publish in order to compete for too few jobs, and institutions are requiring an unreasonable number of publications for tenure and promotion. The requirements for tenure and promotion have been increasing steadily for decades, driven by competition for departmental and institutional “rankings” that bear little relation to the proper aims of higher education and research. The number of jobs has steadily fallen, or failed to increase, because of institutional spending aimed at (i) attracting undergraduate applications, required in some cases to keep institutions afloat amid the ever escalating cost of degrees (due, of course, to the escalation of spending) and in others to raise the institutions “selectivity” to boost public rankings; and (ii) to move senior faculty from one place to another, also in pursuit of rankings. I could go on, but my bottom line is this: the problem is not located in the journals; it’s located at the highest level of the system, which is a tangled mass of perverse incentives produced by collective action problems. It’s one more problem in our society that is systemic. I fear that American higher education has to collapse before it can be rebuilt to solve these problems.

Jason Brennan and Phil Magness provided (to my eyes) fairly compelling evidence a couple of years ago that (tenured/TT) jobs have more than kept pace with UG numbers over the last few decades (“The problem is not that humanities jobs are disappearing” | Daily Nous). If you think they’re wrong, I’d be interested in seeing the evidence.

No, I don’t have evidence over the course of decades. But what do you mean by UG numbers? Do you mean UG enrollments? I would imagine that TT jobs *do* keep pace with UG enrollments, because those enrollments generate increasing income, as tuitions rise. But how long can UG enrollments keep up, now that people realize that taking out loans for a college education is a trap? Families are realizing that college education isn’t always a passport to prosperity, since it can be a passport to lifelong debt. Something’s gotta give.

Oh — and federal funding for higher education is no solution. The real cost of a degree cannot go on rising indefinitely any more than the price of GameStop shares. When I said, above, that “American higher education has to collapse before it can be rebuilt to solve the problems”, I was envisioning a similar crash in demand.

Could it also be that some tenured faculty continue to publish too much in top journals, effectively competing with their graduate students or their peers’ students for what can determine the career of a job candidate but only has a negligible marginal impact on the former’s career except for boosting their prestige and status?

Here’s a proposal. I’m not sure that I agree with the proposal, so I’m putting it out there to see what people think.

Once an academic reaches a certain level of prestige — say full professor at an R1 institution or an h-index of 50 — they no longer need to publish in refereed journals. They can just hang their work on their webpages and post a link to PhilPapers. This would free up refereeing and editorial resources so that more junior colleagues can get more attention.

Of course, there are downsides. (1) It’s not great for your CV if you suddenly stop publishing in refereed journals, and just hang stuff on your webpage. (2) Your stuff is less likely to be read if it’s just on PhilPapers and nowhere else. (3) At some institutions, pay raises depend on publications in recognized venues — not publications on your own webpage or in PhilPapers or arXiv. If you’re sufficiently prestigious, maybe (1) and (2) are not such a problem.

It is indeed striking that anytime the topic comes up it’s graduate students who are told they should not publish but not the utmost secure and already highly successful senior scholars, who then infallibly rise to defend the peer review system as not being the problem or even part of it.

This tends to happen anyway, as senior faculty become increasingly frustrated with peer review and receive invitations to contribute to anthologies. But I agree that it might help if publication in peer reviewed venues became a mark of shame for senior faculty.

It bears repeating that the submission that prompted this entire Daily Nous discussion is co-authored. My co-author is not yet full professor. Each of us teaches at a research-oriented university at which salary increases depend almost entirely on publishing in recognized venues (for the most part, print venues).

Thanks, Nathan. I spoke carelessly. Of course, publishing in peer refereed venues shouldn’t become “a mark of shame” so long as it is necessary for salary increases. I was imagining a very distant possible world.

But the venues that matter for promotion or raises may not be exactly the same ones that the most highly regarded by search committees. Plus the marginal cost for tenured faculty of not publishing in these venues, albeit not zero, is far less than it is for job candidates and junior faculty. So *if* we have to triage it’s hard to see why job candidates and the untenured should not have priority.

PS: this without any prejudice regarding Prof Salmon and his coauthor’s reasons for publishing. This point is orthogonal to the main issue of the OP.

I wasn’t addressing your particular submission. And, at my institution, salary increases also depend (partly) on publishing in recognized venues — so much so, that I’m not yet personally willing to take the financial hit required by my proposal.

Since the discussion seems to have broadened to the general question of how to reform peer review, I’ll make two suggestions (one of which I’ve made on DN before).

1) Encourage more journal specialization. Most of the most prestigious journals in philosophy (Mind, Nous, JPhil, Phil Review, Analysis, etc) are generalist journals. That seems to lead to an equilibrium where everyone is submitting to lots of these journals sequentially, with a correspondingly small acceptance rate, overstressed journal staff, and very long lead times to publication. It also tends to lead to editors having to make decisions, and find referees, for subjects some considerable way from their own area of expertise.

My admittedly-anecdotal impression is that the philosophy of science publishing system works better than in many areas of philosophy, and I think an important reason is that its top specialist journals (Philosophy of Science, British Journal for the Philosophy of Science) are nearly as prestigious within the philosophy-of-science field as the top generalist journals, so that you can bypass the generalist journals and submit to specialist journals direct. Those journals in turn are less inundated and have more expertise to place articles with appropriate referees.

My fantasy would be that (say) Mind, JPhil and Phil Review put out a joint declaration that for the next 3 years, Mind will only accept submissions in metaphysics, epistemology, mind and language; JPhil will only accept submissions in value theory, and Phil Review will only accept submissions not in those areas – and then they rotate after 3 years. More realistically, we could encourage the development of high-quality specialist journals, e.g. by senior people prioritizing them as places to publish. (I’d be interested to hear from people outside philosophy of science as to how the status of the top specialist journals looks in their areas.)

2) Adopt the science practice of getting authors to propose referees. Finding qualified referees who actually know the material is frequently brought up as one of the biggest problems for journal editors, and the actual authors of the paper are extremely well placed to make suggestions. I think a common practice is to use one suggestion from the authors and one referee not on their list.

The British Journal of Aesthetics and the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism are the top venues for aesthetics and the philosophy of art, and I’d say we hold them in as high regard as you do PS and BJPS.

I’d say that we also have a large and respectable stable of second- and third-tier journals.

I think I disagree. My own impression is that even aestheticians regard publication of an aesthetics paper in a “good” generalist journal as a significantly greater achievement than publication in the BJA or JAAC.

As for wider perception: all journal rankings are mostly bunk, but they do track reputation to some extent, and every “all-in” ranking I’ve seen has those two phil science journals (and Ethics) ranked way above the aesthetics journals, usually mixing it with the B+/A- division of generalist journals. So even if aestheticians reckon that the BJA and JAAC are close to par with generalist journals, few others seem to believe them.

(On both points, no comment on whether they should, I’m just dealing with description)

I think I mostly agree about philosophers outside aesthetics and the philosophy of art not rating the BJA and the JAAC as highly as they would PS, BJPS, or Ethics. In fact, I suspect that most philosophers would struggle to name those as the top specialist journals in aesthetics and the philosophy of art, while they wouldn’t really struggle so much for PS, BJPS, or Ethics. I think that’s a consequence of the subfield’s marginalization in the profession, especially at the doctoral level in the US, but I digress.

I think we’ll have to agree to disagree about the first part, though. There’s very little aesthetics or philosophy of art being published in the T20 or so generalist journals (there are a couple of exceptions, but I think they’re notable exceptions). Sure, we’d all like pubs in the T10 or so, but so would anyone else! I think our perceptions of the BJA and the JAAC compare favourably to the journals typically ranked under ~10. (Although the fact that some of those have more name recognition among the general population of philosophers is definitely a consideration!)

Certainly, there’s no question that the BJA and the JAAC are the main venues for work in the subfield, and I think there’s a clear consensus is that they’re the best of the subfield’s journals. In terms of sheer volume, I doubt that the aesthetics and philosophy of art output of the T35 generalist journals combined would compare to that of either journal on its own.

Digression or not, the first point (on which we agree) is probably the most important one, at least insofar as it affects aestheticians’ chances when being assessed by other philosophers (for, e.g., jobs, grants, tenure).

On the second: I think it’s precisely the fact that there is little aesthetics published in those journals that makes it seem like landing an aesthetics paper there is a greater achievement. But perhaps I am thinking of your T10 rather than T20, in which case your “so would anyone” point holds.

Agreement to disagree accepted, but for what it’s worth: I guess my perception is that people tend to think that their “better” papers are those that might be interesting to audiences outside aesthetics, and so send those to the generalist places, while keeping their papers of more narrow interest for the specialist journals. You could query the equation of “better” with “more generally interesting”, of course, and you might also think that the considerations about “reaching a more general audience” are less important now that most people don’t get their journals in paper copies which they browse.

Agreed of course about the status of the BJA and JAAC compared with other journals in the subfield.

In my experience, the vast majority of referees are competent. And the sour grapes factor cannot be ignored in assessing the contrary opinion.

My biggest complaint as a referee is the paper that, although it may contain a great idea or argument, is so poorly written that it would take me days to discern what that great idea or argument might be. My second biggest complaint is the incorrigible author who refuses to seriously address criticism by a mere referee. Moral of the story: Don’t topple the apple cart because of a few bad apples.

Lewis Powell said above: “I’ll just close by noting that I see many people on this thread debating the best entire alternate systems. But we’re not going to schedule a vote as a profession and pick a different journal system.”

And that’s what frustrates me about these discussions on social media: exactly nothing is going to come from them.

I can’t count the number of times I’ve seen or heard the suggestion that referees should be given clear instruction on the purpose of peer review and a basic outline of good practices. It would be a trivial matter to make this a part of the form letters currently sent out to reviewers, or to organise the review form so that it asks very specific questions. Even if only 10% of referees read the instructions, and if it only improves 10% of those who do, that’s still hundreds of improved reports every year. But so very, very few journals do anything like this.

And maybe they have good reasons for not doing it. I mean, I can’t think of any good reasons—many other disciplines do it, it’s not like it would be difficult, and I seriously doubt that it will make it any harder to find reviewers. But maybe there is a reason or several reasons that I’ve not thought of for why it cannot be implemented for our discipline.

Either way, though, it’s an extremely common suggestion which, like all the other suggestions, is not and very likely never will be implemented on any significant scale. And that’s the easiest, most straightforward suggestion there is! So good luck with more thorough-going suggestions. For example, amongst other things and in addition to the above, I think it would be a good idea to (a) have longer abstracts, so that editors can make a more informed decision before sending out for peer review; and then (b) if it is sent out for review, no immediate rejection without any possibility of response unless the referee makes a very compelling case that the work is unpublishable; and finally (c) there needs to be scope for standardised feedback to editors on the quality of a referee report. Of course, none of this is ever going to happen; not any time soon anyway, and certainly not as a result of my having made the suggestion in the comments of a blog post.

So maybe there’s a much more useful discussion we could be having instead. What are the feasible ways in which we could actually get some positive change going? Don’t say: “We could talk about it sporadically on facebook”, because the abundance of evidence is that this will come to nought. We’re not building momentum, we’re just idly spinning wheels. Should we hold a conference on the matter? Perhaps something at the APAs and AAPs and etc., with editors invited? This is a sincere question: what can we usefully do to actually get the ball rolling here?

I’m late to the game here, but here’s a possible model—a credit system, in which journals voluntarily participate, where a referee gets ‘credits’ for refereeing papers, and then credits are ‘spent’ to submit papers. One might give people a one-time gift of 5 credits, or something, but once those are depleted they can only be earned by refereeing.

This would make being a good referee important to a person’s professional advancement, provide a strong incentive to referee, and make people seek out refereeing more than they do. It would also make it so people polish up their papers, ask for comments from friends and colleagues, etc. before sending them out, because it costs them something significant to send it out. I do get the feeling that people just cycle their half-baked papers around to journals, hoping to just get lucky at one journal or another, or at least to get a nice set of comments. I’ve certainly been guilty of sending out work long before it’s ready.

I’m sure this has drawbacks (not least of which that it would be logistically difficult), but just tossing it out there as something to think about.

To make amends for my earlier (genuinely intended sarcastic) comment (like people don’t know their own belief contents?)–my own refereeing regimen was reformed many years ago by a comment from Neil Levy–if you agree to referee then do it ASAP to clear your further agenda–and do a conscientious job. Ever since I have returned submissions within three days, and feel a lot better for it. It’s a good practice and great advice. I’ve not received any requests since retirement, probably because my institutional email was changed, but my new address is on the site linked to my name here.

And apologies if my earlier comment was taken seriously; tone is not the strength of commenting sometimes.

UPDATE: My co-author and I wrote to the journal involved in the incident recounted in the original post, appealing to the journal to consider revising its procedures so that editors might be in a better position to recognize that a referee report of the sort in question should not be relied upon. In reply, the journal did not acknowledge that the referee report is improper.