The Fourth Branch (guest post)

“We shouldn’t attempt to fit ‘outreach’ or ‘engagement’ into one of the existing three categories [of research, teaching, or service]. It doesn’t fit neatly into those categories. And, more importantly, all of us should be doing it as part of our jobs, not just a few of us. We are in an all-hands-on-deck situation.”

In the following guest post, Alex Guerrero, professor of philosophy at Rutgers University, argues that we should count engagement or outreach as a distinct component of the job of professor.

This is the fifth in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

[Posts in the summer guest series will remain pinned to the top of the page for the week in which they’re published.]

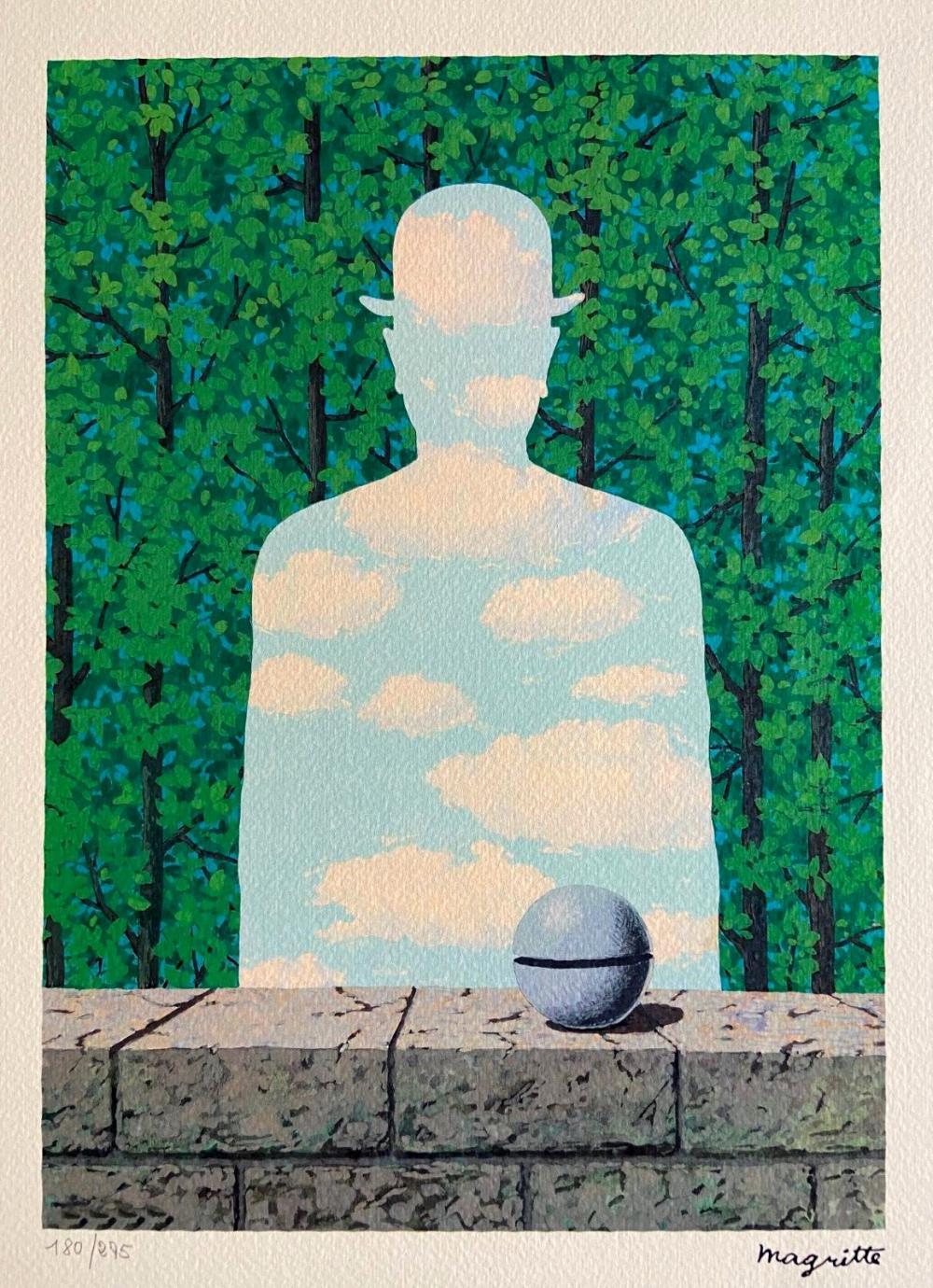

[“The Beautiful Walk” by René Magritte]

The Fourth Branch

by Alex Guerrero

The job of a philosopher in America has been defined in relatively specific terms. These are the terms: research, teaching, and service. How much of one’s life one is expected to contribute to each, the precise percentage and weight, varies from job to job. In some, research is all that matters. In others, teaching is the thing. More rarely, a philosopher wanders deep into administration, lost in a forest of service, and emerges as a thoughtful if pesky manager and builder of things with varying degrees of value. For most of us, we are required to do all of these, more or less well, with more or less joy.

Socrates and Kongzi both might have, for once, been at a loss for words if forced to say whether they were doing research, teaching, or service. But we have contracts, faculty handbooks, promotion guidelines, and legalistic specifications of what we are required to do. None of us are employed as philosophers. We are employed as professors (lecturers, instructors). For the most part, our job is like that of other humanities professors, and unlike that of research scientists and others in STEM fields supported by grants, who do things like “buy out” of teaching and oversee research labs. For us, the job is the core three: research, teaching, and service.

Teaching is the very official role where we are in front of enrolled students, in a class that counts for credit, presenting material, devising and evaluating assignments, and figuring out ways for students to learn what we take to be important about the subject. Our teaching responsibilities are almost always defined by the number of courses taught per academic year, spread out over semesters or quarters, often specified in terms of level and number.

Research is publication. We might wish it were instead about ideas, figuring new things out, moving knowledge forward—regardless of whether that results in articles in peer-reviewed journals or books in academic presses. But we know better. You need 8 publications for tenure in B+ or better peer-reviewed journals. Or 1.5 per year on the tenure clock. Or whatever. What “counts” for research, and how much it counts, is usually clear, even if promotion requirements are rarely specified in detail. Post-tenure, although research productivity factors into further promotions and merit raises, the sense in which it is “required” becomes considerably murkier.

Service is what is required to keep up the pretense that universities and colleges are run by the faculty, rather than by a distinct managerial class. We “serve” on hiring committees, as undergraduate and graduate program administrators, on curriculum committees, on admissions committees, in organizing colloquia and events, in putting people forward and evaluating them for tenure and promotion, as chairs and vice-chairs, deans and deanlets, and on committees for every domain of human complaint and frustration—these are the core of internal, university service. We serve our departments, schools, colleges, and universities. Many of us expand beyond this to engage in service to the “profession”—running academic journals, professional associations, planning workshops and conferences, creating and supporting broad mentoring and inclusion efforts, and so on.

Most of us were just dropped into this world of research, teaching, and service. I’ve never seen anyone try to justify why these are the three parts of the job. As many have noted, they don’t fit together all that naturally. What makes one an amazing teacher might have nothing do with what makes for a groundbreaking researcher. And we almost expect that whatever makes us good at those things will make us inept at, or at least impatient with, most kinds of “service.” Our graduate training programs do very little to train us to teach, or to administer anything or manage anyone.

The explanation for the three branches seems to be a historically contingent one, with the modern college or university coming to exist with a dual-purpose mission of educating students (teaching) and advancing knowledge (research), and service comes along as a third thing essential to preserving various values relating to those first two. Specifically, the values of academic, expert peer review (for admissions, hiring, publication, research evaluation, promotion) and academic, expert curriculum and course design and implementation.

There are, of course, many ways of rethinking this basic three branch setup, and many institutions that have already reconfigured things so that people are hired into jobs where they will do just one or two of those three things. I don’t want to wade more deeply into those waters. Instead, I want to suggest that, given the pressures confronting colleges and universities, sustaining those institutions in their core dual-purpose mission of educating students and advancing knowledge requires introducing a fourth branch. I’m not sure what name for that fourth branch is best. Here are my two favorite candidates: outreach and engagement.

The basic argument for the fourth branch is simple.

Colleges and universities are supported (1) by the general public, through government funding; (2) by students and their families, through tuition and fees; and (3) by rich people, through donations. What education and what knowledge will be pursued in colleges and universities is not set in stone; it is, rather, a function of what those three groups want and demand. If we want philosophy to be part of the education and part of the knowledge that is pursued in the years to come, we need people in those three groups to want and demand philosophy. And for people in those three groups to want and demand philosophy, we need to reach out to them, engage them, make them aware of what philosophy is and why it is wonderful and valuable. Given what philosophy is, and given our contemporary situation, that task is monumental, and must be undertaken at many different levels, in many ways. No small number of us can do it on our own. Therefore, it should be a part of all of our jobs—quite literally—to do this work.

(We can substitute in almost any humanistic field for ‘philosophy’ in the above argument, with similar implications for a needed fourth branch for the rest of the humanistic fields.)

The basics of this ‘demand side’ story are familiar. Many students and parents think of college and university in terms of relatively short term, career ambitions—how will this major, this degree, this school help me get a job. Many states and nations have begun taking a similar attitude toward all higher education, thinking in terms of contribution to economic productivity. Little actual empirical investigation is involved in deciding that humanistic fields, and fields such as philosophy, in particular, don’t do well by this score. But that is a common public perception. And it is understandable. It seems plausible that a degree in business, health professions, computer science, engineering, or biomedical sciences (the five largest growth majors over the past ten years) would be a more direct route to a job than a degree in English, history, or philosophy (three of the majors that lost the most majors over the past ten years).

There are other factors that affect demand. STEM fields are intimately connected to industries and occupations outside of the academy, so that one might have encountered a person with background in that field. We no longer have the same kind of elite, quasi-aristocratic veneration of those humanistic things that every “educated” person must know. STEM spends more time in the news, as breakthroughs in tech, science, and computing get regular reporting and discussion, and result in products in our pockets and dreams on our screens. In the United States, quality exposure to literature, philosophy, and even history is rare prior to college or university, with many students not having encountered any philosophy before college, and having encountered history only as rote memorization and literature only as forced reading.

Behind the idea that colleges and universities have a dual-purpose mission of educating students and advancing knowledge is a mostly implicit idea about what education and knowledge is valuable and why. For those of us working as professors in a subject domain, we almost certainly see the domain as valuable, and can offer many different compelling reasons why it is valuable, pointing both to intrinsic or final value of the subject, and to instrumental benefits of education and knowledge in the domain. We can go on and on about personal transformation, what it means to be human, learning to think critically about what is important, becoming a democratic and cosmopolitan citizen of the world, and so forth. But for those not already in philosophy, where are they supposed to hear the good news?

It is easy to vilify the administrator class, focused on the bottom line—bottoms in seats, donations to “development” offices, legislative support for public institutions. But it is not their fault that higher education is funded as it is. It is not their fault that we, the professoriate, don’t have unbridled power to force people to study those subjects that we see as most valuable. Professors like the idea of being in control: we get to design the curriculum, plan the syllabus, pick the readings, develop the research projects, evaluate the work, decide what should be published, determine who should be admitted, hired, promoted, esteemed. This all seems right and good to us, given our knowledge and expertise. But that is not the system we have with respect to the very basic facts of higher education in most contemporary political environments. We might wish for administrators who could hold the line, fight the battle for us, make the case for the importance of philosophy and the humanities. And some of them can and do. But many operate in incredibly difficult economic and political environments. They can’t change the basic facts about whose demand matters. And they can’t even do much to affect the substance of what is in demand. They need help. And—at least given our knowledge—we are well positioned to provide it.

Many of us are already involved in various efforts to broaden exposure to and engagement with philosophy. Most involved in this work aren’t doing it thinking to “increase demand” for philosophy, but it plausibly has that effect. There are obviously central enterprises: exposing children and adolescents to philosophy and serious humanities in K-12 education, for example, something that many are already doing. Writing “public facing” philosophy that appears in newspapers, broad circulation prestige venues, trade books, and so on. Creating online philosophy courses and videos and other broad access materials like podcasts. There are also more local, more intimate efforts: organizing a public philosophy week at a public library, running a philosophy club or ethics bowl team at the local high school, organizing community book groups and “meetups” to discuss philosophy, running “ask a philosopher” booths at the train station, farmers’ market, or mall. These activities bring philosophy to people outside of the academy and bring people into philosophy, giving them entry points and a better sense of what the subject is and why it is of value. They also are a lot of fun. And a ton of work to do well. And, for the most part, they are treated as outside of one’s job, falling outside of the big three: research, teaching, and service.

For those involved in this work, a common argument is that it should be included under research, teaching, or service—depending on the details. In a few places, “engagement” work is already included as part of one’s official job requirements. In more places, efforts are being made to think about how to include this work under research, or teaching, or service. I’ve spent the past year on a committee at Rutgers on a “Task Force for Community Engaged/ Publicly Engaged Scholarship,” focused on questions of definition (what is it, what counts) and evaluation (what metrics are available and appropriate, what standards should be used) of this kind of research. In serving on this committee, I’ve learned in detail about dozens of similar efforts at other institutions. In almost every case, the discussion is focused on how to credit the work being done by a small percentage of professors who are doing some “community engagement” or “public facing” work. Can it count instead of other, more traditional academic research? Can it count for teaching or service?

I want to suggest that, for those of us in the humanities, we should understand the importance of this engagement work to our core dual mission of educating students and advancing knowledge in our fields, and we should stop trying to shoehorn it into the traditional three categories. In the same way that service is required to sustain certain valuable features of how education and research is conducted, engagement is required to sustain certain valuable features of what education and research is conducted. Professorial “service” is required due to internal, contingent features of running a college or university, as something instrumentally important to enabling high quality education of students and to advancing serious research and knowledge. In the modern political and economic context most of us are in now, professorial “outreach” or “public engagement” is required due to external, contingent features of running a college or university, as something instrumentally important to enabling high quality education of students and to advancing serious research and knowledge in all academic domains that are of genuine value, including philosophy. We shouldn’t attempt to fit “outreach” or “engagement” into one of the existing three categories. It doesn’t fit neatly into those categories. And, more importantly, all of us should be doing it as part of our jobs, not just a few of us. We are in an all-hands-on-deck situation. It’s not clear that even this huge shift would be enough to save the humanities, but it affords more hope than doing nothing and just praying for favorable shifts in the demand curves.

So, the proposal is this. Add “engagement” or “outreach” as a fourth component of the job of professor, along with research, teaching, and service. The exact percentages might vary, as they already do, across institutions. One model might be 35% teaching, 35% research, 20% service, and 10% outreach. Just as with service, there would be a variety of ways of satisfying the requirement. And it might be assessed over several years, rather just in one particular year.

In addition to the familiar forms above—creating and running K-12 programs and clubs, public facing writing, online courses and spaces for public philosophy discussion, podcasts, local events and courses and reading groups at libraries and other community venues—there might be other work that would count. Creating and publicizing materials about philosophy and its intrinsic and instrumental value, developing materials to connect philosophy to prominent issues of the moment, connecting philosophy to locally popular elements of colleges and universities (such as college sports), strategically lobbying local and state political officials to help explain the value of philosophy and to think about ways in philosophy might be relevant or useful given their political agenda, developing white papers and strategic plans to encourage businesses and industries to seek out philosophy graduates and build philosophy alumni networks, even working on philosophy-related fundraising (either through or, where permitted, outside of, the development office). We need to do work at many different levels, in many different venues and spaces. New Yorker articles and popular books are important, but insufficient to reach or affect the very broad, heterogeneous communities whose interest and demand is relevant.

Just as with service (and teaching and research, for that matter), we shouldn’t expect that everyone will be equally good at or equally drawn to every aspect of outreach. And, just as with service, much of our evaluation of the work will be somewhat less precise than our evaluation of teaching or research. Norms and guidelines will need to be developed and adjusted over time. There is also the question, as with teaching and service, of how to train people to do this work well. Much of the work being done by committees like the one I’ve been on can be of help in thinking through these issues. None strike me as insurmountable.

The basic hope is that, by requiring everyone to do some outreach and engagement work, we can get many more people involved, and have a correspondingly greater effect on the broad understanding of philosophy and its value, with a hoped-for uptick in interest, support, and demand.

There are other potential side-benefits to creating the fourth branch. One is that it might mean that the public face of philosophy will be much more complex and multifaceted, so that it isn’t entirely dominated by a few prominent people who are skilled at prestige publishing or personal branding or whatever we want to call Žižek’s skillset. Another is that, as most people who have done this work will attest, engagement and outreach work provides a kind of beneficial feedback, potentially improving the quality of one’s teaching, research, and service, as one steps back from those activities and considers and attempts to communicate about their value, and to share philosophy with people who have not encountered it before. A third is that it might enable and prepare philosophers and other humanists to push back more effectively against the tendency for humanistic and normative concerns to be overrun by the march of technological, scientific, and commercial “progress” and “innovation.” And it might help the broader public see, raise, and respond to these concerns for themselves, even without any university training in the field.

There might be a worry that focusing on demand and broad interest sets up a zero-sum competition. We might do better, but that will mean some other field, perhaps with a harder case to make, will do worse. Perhaps, although I think a broad push from humanists in this regard might make a considerable difference to public understanding and public perception, even about the basic role of colleges and universities and the value of attending those institutions. Much greater, more structurally supported and organized efforts from professors in this regard might help alter the discussion and push back against the view of higher education as just some kind of pre-vocational training for those who can afford it. Most optimistically, it might alter the public funding dynamics of college and university, reasserting the ideal of affordable liberal arts, humanistic higher education for all as part of an important public component of a genuinely democratic, flourishing society.

Earlier, I mentioned that administrators are often limited in the ways in which they can help us. Here is one: help the humanists help themselves, by building a fourth branch, focused on engagement and outreach, into our jobs. In some cases, we could begin doing this somewhat informally within departments, setting up service positions focused on outreach, and then treating that work as part of service. But, in my view, it will be better to build it in more structurally, with a broader requirement for everyone, and allowing a broader array of ways in which to contribute.

If we want philosophy to survive, we need people to understand what it is and why it should survive. We can’t just rest on our historical laurels or on “get off my lawn” arguments that simply insist that no serious university can exist without a philosophy department. We might be right. But we also might just end up surrounded by unserious universities.

Other posts on public philosophy, engagement, and outreach.

In a healthy democracy, outreach wouldn’t need to be a contractual part of one’s job. Each citizen would recognize that they should communicate what they know and value in public spaces. Of course, a humanistic education is probably a prerequisite for most citizens to recognize that duty and co-create a healthy democracy. So, maybe Guerrero’s proposal will have to do for now.

Good point!

But, I think you need to distinguish between what citizens do as citizens and what philosophers do as philosophers.

For the latter:

Note: I’m a Persian speaker, so I’m sorry if my point is not clear enough!

If we start out as professors of philosophy looking for ways to preserve our jobs and whatever measure of social prestige come with them, then some form of outreach or public engagement may seem necessary as a form of marketing. From this standpoint, we must do whatever we can to ensure the continued place of philosophy in the academy.

If we instead start out as philosophers looking for ways to preserve and perpetuate philosophical activity and philosophical communities, then we should engage in outreach or public engagement in order to create or sustain communities and institutions that can support that activity. From this perspective, we should think seriously about whether and when the academy is the best or most important home for philosophy.

In speaking of the job of a “philosopher,” and invoking ancient philosophers like Socrates and Kongzi, Prof Guerrero invites us to think he is addressing the second perspective. But the details of his analysis make it clear that he is addressing the former. Indeed, not only is he addressing only academic philosophers (and, more broadly, academic humanists), but he is only addressing those in full-time, typically tenure-stream positions. The adjuncts and the unemployed are not part of the “we” who must add the category of ‘outreach’ to our jobs.

There is nothing wrong with addressing that audience, but I would hope that the various crises facing the modern academy would lead us to think seriously about the purposes of the academy for philosophers, how well it is serving those purposes, and what alternatives there might be.

I’m all in favor of people choosing to engage in philosophical outreach of their own free will, as there are plausibly many goods to be gained from it. I am also in favor of us encouraging each other to do it, and perhaps rewarding it under existing requirements for service (which is how my university counts it).

What I am less convinced of is the idea that we should codify it into our official job requirements as a fourth branch to be counted and evaluated separately from (and in addition to) all other things we are already required to do.

Why? For many reasons, among them that it would for all intents and purposes enable people in power (administrators) to demand *25% more work* from all of us in perpetuity on top of all of the other constantly-rising demands we face…just so that we can keep our jobs. Peak capitalism indeed.

Agree with Facepalm.

If we’re talking about ontology, yeah sure, outreach is plausibly distinct from service. But pragmatically, it’d be much easier to argue that outreach is a type of service than to overhaul retention, promotion & tenure requirements and processes in order to carve out a fourth branch…which can be exploited or even weaponized by administrators.

We need less bureaucracy, not more of it.

Yes, having spent a long time on this particular issue, I can see a case for folding it into service at some institutions.

I don’t think all that much ‘overhauling’ would be required, however. Nor do I think much new bureaucracy is required. In my experience on tenure and promotion committees, service is evaluated almost entirely just based on whether there is anything in the box at all. I can’t recall a single case in which it seemed like a tipping factor for or against tenure or promotion. The chair/department’s letter will spend a little time mentioning what service was done, but it doesn’t require any elaborate bureaucracy, there are no ‘service evaluation metrics’ calculated beyond just the question of how much the person did.

On the proposal as envisioned, outreach would be very similar, if even less important/central in almost all cases. No elaborate bureaucracy. No overhaul required. Just another box on the form and a wide range (as with service) of how much people have to put in that box.

As for the ‘this enables people in power to demand more work’ argument, I guess I don’t see it, given the way that service is currently considered.

At many places, assessment and assignments of service are fairly informal: you do the service requested of you by your department or university, and they keep some eye on that so it is fairly balanced. At other places, they have precise point systems, with different service jobs ‘counting’ for different points, and everyone having a set allotment.

In the informal places, outreach would be similarly informal, and (at least at places that embraced it in a serious way) there would be an understanding that the other three areas would be reduced a little. You would have to do something to put it in the box, but there would be a lot of latitude in what or how much, and it might be balanced against other things. There’s always a risk of some unfairness and slippage at such places, and worries about some people doing much more than others, just as there is with service. But that might be one reason to lump it in with service, as a different kind of service, as Patrick suggests.

In the formal places, outreach would just be another thing that was assigned points, and would be counterbalanced according to the %s as determined by the particular institution.

It is of course possible that at some highly exploitative institution they will not take the % thing seriously at all, and just demand more work, so that you are required to do 110% or 125% of what you were previously. But at those places people will (and maybe should) just do a shitty job with service and outreach, too, I guess, check off the boxes in a minimal way so as to keep at 100% of what they were before, and be maximally frustrated with their exploitative institution. But surely this is already a problem for anyone in such a job, right, as they would seem to be able to just arbitrarily increase your teaching load, or require you to do a bunch of extra online teaching or grading, or require more service and teaching by not replacing people who retire, or slash funding for administrative staff and require professors to do that work, too, or… I mean, yeah, that seems really bad. I am sure there are many people at such institutions. But I guess it seems they hardly need to wait for this kind of reform proposal to come along to exploit you, given that they can do that within the existing three categories as much as they want. And it would seem that focusing on those cases would mean pretty much anything at those places would be bad news. It’s a bit hard to imagine the case where the administration toes the line incredibly responsibly with respect to the current three categories, but adding in a fourth would allow them to just pile on and ignore all contractual specifications, etc. At any rate, one hopes those cases are not a majority of cases, and the reform might be useful even for eventually transforming some of those jobs into something slightly less exploitative…

In Scandinavian countries, this is a reality, in Sweden it is called “Tredje uppgiften”. It is called the third task because “service” isn’t recognized as an autonomous area of obligations. Theoretically, I find this to be a good idea. In reality, however, it leads to several problems such as the difficulty to assess the quality of public outreach.

More diversion from actually doing philosophy – yay!

Outreach can actually consist in doing philosophy, just as most research and teaching can consist in doing philosophy, and a good amount of service too (refereeing papers, organizing conferences, sitting on committees, etc.)

But as with all of these, if you’re doing these in a way that involves engaging with others, rather than as a solipsistic activity, that engagement with others will involve a lot of stuff that feels non-philosophical, like writing up your ideas so they can convince a reviewer that you’re doing interesting philosophy, and grading student assignments to see if they actually learned things, and writing up reports destined for an editor to see.

You have a very broad conception of ‘doing philosophy’. I meant it in the narrower sense – researching and writing texts, and discussing them with other philosophers privately, in print, in workshops or through lectures.

“You have a very broad conception of ‘doing philosophy’. I meant it in the narrower sense – researching and writing texts, and discussing them with other philosophers privately, in print, in workshops or through lectures.”

You do realize that by your definition Socrates pretty much never did any philosophy don’t you?

Good point. There’s still a ravine between what Socrates did and the proposal above.

Hi Thomas. Here’s how I think of it. I am incredibly fortunate to be in a position where I could spend a very large percentage of my time just “doing philosophy” in the “narrower” sense you describe.

But I see these terrible reports from other places where whole philosophy departments are being shuttered, or faculty are being laid off. Not to mention the general trend away from funding new TT positions for people in philosophy, as faculty retire and are not replaced.

I see this proposal as suggesting a way for each of us to do a little of something that isn’t (perhaps) just our own narrow research that will make it possible for many more people to have a chance to do philosophy.

I also think that there are many ways to do outreach that are also “doing philosophy” in just about any plausible sense we could articulate.

Hi Alexander. Thanks for the reply. I agree that outreach work is important and I don’t doubt that your proposal is well-intentioned, of course. But to me the formalization of yet more job tasks seems likely to affect junior academics much more than senior ones. Pre-tenured faculty, postdocs, adjuncts and PhD students would have to perform this fourth branch to a very high level in order to become or remain competitive for a tenured job. Whereas tenured faculty would face no real pressure to do so. It’s similar to the added pressure to show how much one has done to further diversity. Tenured faculty can put a lot of effort into it (as you do), but if they don’t, the personal consequences are minimal. This isn’t so for non-tenured philosophers. If your proposed new requirement is applied solely to tenured faculty, with real incentives added, then I’m all for it.

I see that this article aims at the humanities – but I think it’s wrong to think that the sciences don’t need to be doing exactly the same thing. From a standpoint in the humanities, it can feel like scientists get all the goodies, but actual scientists often feel like they are nearly as ignored as humanists, in favor of engineers and people doing business or law or whatever.

However, the sciences have organized themselves to make outreach a formal part of their work. At the university level, they are still organized around the three branches of research, teaching and service (sure, there’s a lot of “buying” out of undergrad teaching, but there’s correspondingly much more graduate education in running labs). But grant applications usually have a section where scientists are required to describe some outreach efforts that they will engage in as part of their work. And scientists have been trained to talk to the university publicity office every time they publish a paper, to get some outreach on that end too.

Once outreach has been institutionalized this much, to a lot of people it feels like a bs hoop they have to jump through. But I think it’s a valuable one, just as a lot of the steps involved in research, teaching, and service are. It may be that 90% of outreach attempts achieve nothing of value, but we may have to engage in all of them to get that 10% that do have impact.

I think administrators at my university would love this – another way to demand even more work from us for no additional pay. They’re certainly not going to cut my course load or research expectations to give me time to do something else.

Given your description, I would think that administrators at your university would hate this! I doubt that administrators at your university are motivated by increasing workload – I suspect they’re motivated by certain kinds of output that faculty produce, and they will like this only if they think it will increase the output of that kind that they can get from faculty. If what they value you for is the butts in seats in your classes, or the university name on journal bylines, then they’re not going to be interested in this proposal at all, since it will take away your attention from those things.

But if they like those things *as well* as liking their university’s name in the press for other reasons, then they might be interested in this proposal. But they would also have incentive to implement it in a way that results in a greater balance of what they’re interested in – they’re hopefully not so naive that they think they can just increase expectations in all categories at once. (And if they are that naive, then there’s no worry about this proposal – they’ll just ask you to teach more classes and publish more papers already.)

This isn’t relevant to the main proposal, but in passing while describing the current set-up of research, teaching, and service, the OP says,

“Our graduate training programs do very little to train us to teach…”

This is true as a matter of fact, but it shouldn’t be true. Precisely because grad school largely is a training program for future work as a professor, and teaching is one of the main job responsibilities for future professors, teaching people how to teach effectively should be at the center of all graduate programs.

> And, more importantly, all of us should be doing it as part of our jobs, not just a few of us.

And how much are you getting paid for this new work?

I do not dispute the wisdom of outreach, but I confess my initial reaction is one of exasperation given the things already demanded of me.

I tend to see outreach come from philosophers of name-brand universities. This could be due to three factors: (1) one reason they are at a famous university is because of their skill in outreach; more likely, (2) the public (and certainly media organizations) don’t care as much what I have to say from my regional teaching public university; (3) professors in name-brand/R1 universities have teaching loads that make outreach feasible.

So is this activity something the vast majority of faculty could ever really pursue? I was surprised to not see OP discuss workload outside of Rutgers/Oxford.

Thanks for the comment. Yes, we should think of workload. For some reason, these conversations often go to thinking about the already exhausted person teaching a 4-4 load, running their struggling undergrad program, having to serve on several university committees, perhaps all while junior and under pressure to publish and do many other things. Agreed, I wouldn’t want to add ‘outreach’ to their list of responsibilities if nothing is going to be reduced or subtracted. The proposal involved subtraction and reduction elsewhere, but perhaps that isn’t a possibility everywhere. The proposal also kind of assumes that the burden would fall relatively less on junior people and more on post-tenure people, just as service responsibilities do at most places. But we should be clear about all of that, and condition support for the idea locally on those things being the case. Fair enough.

But let’s think also about the hundreds if not thousands of faculty in relatively cushy 2-1 or 2-2 or 3-2 or 2-1-2 jobs, with teaching preps they have done many times already, post-tenure, who are cruising along, not doing all that much service (and in places where large service jobs come with teaching reductions), maybe focused mostly on their research or not even doing all that much of that. There are 146 R1 universities. There are 50+ excellent SLACs. Think of all the post tenure people at those institutions. What I would like is to nudge all of *those* people into doing more outreach work, as a way of paying it forward and helping to support and sustain philosophy for the next 25-50+ years (until we are eaten by AGI or whatever). Some of them do some of this work already. But many of them don’t. Most of them don’t. Not for any particularly good reason, either. Many would be great at it. But it’s not on their radar. Or there is just life inertia. Or whatever.

Also, importantly, by “outreach” I really don’t mean anything limited to publishing “public philosophy” in prestige media or high profile venues. Quite to the contrary, I think we need a lot more of creating local philosophy events, clubs, groups, etc., in Tallahassee and Kalamazoo and Columbus and Walla Walla and Phoenix, and thinking about how to present and popularize philosophy in places and venues much closer to home.

So, I’m very sympathetic with the basic concern. But let’s not ignore the many people who could, without all that much added stress (and maybe a lot of added joy!), do more. (I have been and remain colleagues with many of these wonderful people!) Indeed, it strikes me that if we want to make things better for philosophers in every kind of job, those in relatively reasonable workload jobs need to do more on this front.

Thank you for the helpful response–seems very reasonable to me.

You say “For some reason, these conversations often go to thinking about the already exhausted person teaching a 4-4 load..” I guess the reason I went there is because that is me, and most philosophers in the profession, even when only considering those endowed with the privilege of having a tenure-track position in the profession. So I do not think the reason why we go to thinking about that person is mysterious. I think there’s a very good reason to often go to thinking about that person (though not to the exclusion, as you suggest, of people in other situations, for whom your proposal makes a lot of sense!).

I agree with Junior Faculty – the reason people start off by thinking about those in non-TT positions/adjuncts and those with high-workload TT positions is because these are the vast majority of people who teach philosophy in the United States.

To echo this from a job market perspective: please nobody make me write an effing “outreach statement”.

I might be jaded here, but whenever some senior person comes out with “philosophers really should do X”, departments react by saying “let’s require this of our next hires”. In most cases, this one included, it is probably right and important that we do X. But consider who bears the brunt. It’s never the senior, tenured faculty.

Our grad students already have to do a ton of little semi-official qualifications they have to achieve to be competitive on the job market *in addition to their dissertation research*, with practically no administrative or financial support.

Yes, agree that this would be the wrong way to do it. That’s why I’m pitching it as a component of the job, and really (as with service) part of the job of TT faculty, and really (as with service) part of the job that we should and often do (in healthy departments) place mostly on the post-tenure people.

Two other things. One, early career people already do a ton more of this and this would be a way for them to get more credit for that work. Two, the motivation for the proposal is focused on the need to increase demand for philosophy, which very directly goes to the supply of TT jobs in philosophy. I don’t see this just as another nice thing to do. We need to be thinking about how to solve the job shortage problem. And yes, that really should be on all of us, but particularly those of us with tenure in stable, relatively cushy jobs (those who are least personally and intimately worried about the shortage of jobs, perhaps).

The Charting Pathways of Intellectual Leadership (CPIL) initiative in the College of Arts & Letters at Michigan State University might interest folks in this thread. Driven by the tension between what is considered valuable university work and the traditional research-teaching-service classification triad, the CPIL framework asks faculty (and staff) how they shared knowledge, expanded opportunities, and engaged in mentoring and stewardship activities. This framework for intellectual leadership is considered supportive of traditional RPT criteria (books, articles, and grants), but also allows for the articulation of new criteria, including publicly oriented scholarship, outreach, and community-engaged and non-profit work. MSU’s College of Arts & Letters has also worked with each unit to apply this framework to their governing document. They have a nice visual in this short video that shows how they aim to support work; and here is also an overview paper of the initiative.

While I’m not at MSU to know how this is working in practice, as someone whose academic profile has a significant component tied to public outreach and engagement, I find it a super interesting example of what value-aligned institutional practices and change could look like. I also think it’s an interesting model because, for some academics who do publicly engaged work, their projects don’t nicely and conveniently fit into these branches in an easily quantifiable way. They overlap and inform each other a great deal. For example, I produce philosophy/research papers that are deeply informed by my outreach, which also involves aspects of undergraduate teaching and graduate student mentoring.

Everyone I’ve told about the MSU initiative finds it a fascinating development, even institutionalists who like the old model and categories. I recommend everyone take a look at it.

It’s worth pointing out that public-facing work can be helpful within the academic discourse as well. If you are somewhat of an outsider to some sub-sub-discipline in philosophy (or any academic field for that matter), often the best entry points are some articles written by, or interviews or podcasts with, an expert in that area. There is a considerable amount of tacit knowledge in any academic conversation which the insiders don’t feel the need to make explicit in academic publications since the in-group share the relevant tacit knowledge. But when communicating with a broader audience, one must make explicit some of those tacit presuppositions, and that can be instrumental in clarifying the rules of the discourse to philosophers and academics who aren’t part of that niche discussion.

Shameless plug: you can see an example of this kind of work at our page for the REACH initiative at Salisbury University. http://www.salisbury.edu/reach

Following some of the points already made, I’d advocate that this sort of engagement actually enriches philosophical research and teaching in exciting ways. It’s question begging to say that engagement isn’t a part of “actual” philosophy because that’s simply an appeal to the idea that definitionally, philosophy is only really done when it’s not engaged in the way described. In my own experience this sort of “actual” philosophy is sometimes thrilling and sometimes meh, but it is always unclear to whom this kind of philosophy is addressed and on whose behalf it speaks.

Having stated my general enthusiasm, I would point to what I would see as a major deficiency in the scope of the original argument, that is, it doesn’t speak at all about what would need to be the case for engagement serving as a form of institutional empowerment for humanities/philosophy professors. Will public engagement be met with enthusiasm when the public wishes to change what a university is for? When a wrong action by a university has caused harm to a community? When trust is lacking in higher-education for a defensible reason worth exploring? What happens when engagement reveals something that would require a critique of the activities of a school or department across campus? A senior colleague?

It is important that universities are engaged in a very diverse but also concrete sense of “communities” (local, epistemic, institutional, etc.) and that this engagement has the capacity to generate critical thinking about the status quo and the common good in relevant senses. Think of the way philosophers can productively contribute to criminal justice reform, public ethics and transparency, health care, etc. And I’m in broad agreement with the idea that such activities are in our self-interest as professionals. It is strategically beneficial for the role of humanities in following through on university missions, and promoting the public understanding of what it is that philosophers and humanists can do. But good critical relationships are, well, relational, and to engage in a community means to revise what it is that (philosophers, humanists, universities) do, how they make decisions, how they seek to include excluded voices, understand their own barriers and bad practices, even the ways in which universities done wrong have caused harms to communities and individuals, which are typically not well reported on or are well understood by their own faculty (note the 2021 Penn St. Anthropology faculty apology for the use of human remains from the MOVE bombing from Penn St. as an exception). So while I can see lots of excitement from administrators on the concept of engagement when understood as a critical engagement by faculty with the community or other institutions, I’m not at all sure that faculty will be supported when they are morally or otherwise obliged to direct the critique the other way, i.e. discover community and public realities that require that universities themselves be the subject of critique and change.

So I add that in addition to the already complex landscape of engagement, we’d need to think about the limits of institutional willingness to embrace an empowered form of engagement, e.g. where faculty freedom and labor will be protected even when the result is facilitating a critique of our disciplines, practices, and institutions -by- the community. Of course, I think that “actual” philosophy should be excited about this because it is an opportunity for critiquing ourselves and searching for the best sense of what philosophy ought to be doing, given information about the priorities (ethical, political, epistemic, etc.) of a concrete community or institution with which one has a substantial and long-term commitment, about which one has institutional wisdom, and hence through which one has access to a form of community-informed insight. But make sure you get those assurances of institutional buy-in up front, on paper, and with broad consensus for support. Because engagement, if it is philosophically worthy and not performative, can get pretty rocky pretty quickly.

I’ve talked to Alex extensively about this issue and am very excited about this work advancing this initiative at Rutgers, so I’ll use this opportunity to register one difference of opinion.

I don’t think public outreach should be a requirement of everyone in a particular department. I think its okay to have a division of labor based on talents and skills. There are plenty of people I wish were never required to do university committee service, and some who I wish were never required to set foot in an undergraduate (or grad) classroom, and quite frankly plenty who I wished weren’t required to write papers they don’t care about and are only publishing to get over some hurdle at their teaching-intensive non-research institution. It should be okay to have very good public outreach individuals in your department while everyone else is happy to stay in their research niche, others happy to teach their same 4 courses, and still others who are working to become Dean. Some people might be good at many areas. Example- much of PIKSI and various summer programs are run by very well-known researchers.

What we need first is to get rid of the inequality associated with excellence in some of these categories and not others at certain kinds of institutions that could really benefit from people who excel in one but not others. Many excellent teachers of philosophy aren’t valued at R1 institutions, many young TT people I meet who want to do outreach (and maybe even did it as grad students) have to wait because their institutions don’t count it at all, and even if they are tenured, will continue not to count it).

I think what Alex says is all true, we take for granted that philosophy departments should have good philosophy researchers, and they should have good philosophy teachers, and they should have good administrators who can help run things. Having a good public outreach person/program that makes the local (or national) community see the value of philosophy is something we haven’t taken for granted, and we should. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it should be a requirement of the job for everyone. It depends on the department and institution.

Hi Barry! Yes, I actually had a longer version of this when I had a kind of ‘menu’ model, in which most jobs would be structured so that a person picked 2 or 3 of the 4, and that departments would then be structured with some balance of people to cover all 4 of the branches, but not all on a ‘each-person-does-all-4’ model. But that got complicated for a simple model, and it was harder to get the basic argument for covering the fourth branch–in some way or other–in view. But yes, I am very much in favor of institutional flexibility and a range of design options…

(Also, thanks for our conversations on this, which have been very helpful for my thinking about it!)

Again, I notice that discussions of public philosophy (here and elsewhere) and (now) engagement usually don’t take (the apparatus of) disability into account. Disabled philosophers are generally disregarded in these discussions. Examples of public philosophy and now engagement that get offered in these discussions, for instance, never refer to Dialogues on Disability, the series of interviews that I conduct with disabled philosophers. Yet the interviews are so very important to disabled philosophers, disabled academics more generally, and the wider disabled population. They serve both internal and external roles and functions, making space and community for disabled students and faculty, as well as drawing attention to philosophy from non-philosophers and prospective (disabled) philosophers. Many disabled philosophers find it difficult to imagine what it would be like to be in the profession, including as a disabled student, without the series.

What are “public philosophy” and “engagement” when you identify with a social group that is systematically excluded from philosophy? When “engagement” revolves around employment which, as a disabled person, you are most likely to be excluded from? (Most “working-age” disabled people are unemployed due to widespread ableism and inaccessibility.) Some disabled people cannot work, given current social arrangements and infrastructure.

Next month, I will post the 100th installment of Dialogues on Disability which will comprise blurbs from many of the past interviewees who convey what the series has meant to them and the way in which they situate it in the context of the discipline and profession, as well as society more broadly.

Dialogues on Disability is a great and important resource, and an important way of broadening philosophy and bringing philosophical ideas and insight to the broader public. Thank you for your work on it.

Over my 40 year career I did uncounted public presentations and published dozens of letters in the Milwaukee Journal-and/or-Sentinel (and got death threats for defending reproductive health and rational gun control; one letter about freedom from religion received *from the publisher of our local paper in an editorial* a printed intimation that I should go to hell since I didn’t believe in it!) but did all that only because I felt that the privilege of my position as a state employee required that I participate in the public sphere advocating for what I saw as the public good. That’s because I have always believed that a progressive democratic society must view education as such–a public good. There are incredibly strong forces today that see public-funded higher education as anything but a necessary evil in opposing their lust for control–especially over the nature of education–and we must do everything in our power to resist that.

I’ve done a fair bit of work in public philosophy and I can’t say I ever struggled to find philosophers willing to participate (we are not usually a group afraid to take the mic!). What was much more tricky, by several magnitudes, was finding financial support—for infrastructure, for admin support, for various technicians etc etc. So I think a proposal such as this might be good for public engagement not because it encourages philosophers to engage with the public but rather because it may encourage investment and spending in the infrastructure required.

During my experience as a very mature philosophy student at Edinburgh, 2009-2013, it became clear that the academics were driven in pursuit of their citation index. In lectures and seminars I could look out at the Edinburgh populace going about their daily lives totally unaware of the Aristotlean practical wisdom that could be available to them, if only those with it would reach out. Asking the Thalean question: What is It? This would provide the individual with a start on a reflective life. This thought alone should be enough to make philosophy a core subject at every level of complusory school education. It is for academic philosophers to shrug off the strait jacket of the citation index, that leads to papers on obscure matters, read only by people who themselves cite them in further obscure papers. Relevance is everything. Philosophy is too vital for the mental fitness, and the vigour of critical thinking within a population, to be the mere plaything for academics locked in their offices, typing more papers only for other academics to read. Leave the office, and go out to the agora.

What are the criteria for this, or who would be in charge of deciding what the criteria are? If I just tweet a lot, is that outreach? Does it matter how many followers I have? If so, would that incentivize trolling and other ways to gin up clicks? It’s easy to point to good examples of people doing this, but if it were institutionalized, I fear the bad examples would rapidly outpace the good ones.

If I am a political philosopher who canvases for the Democratic Party, does that count as outreach? (I mean, it would be counted, of course, but does it?)

Philosophy is (slowly) coming to the same realisation that the scientific community came to in the 1990s: that outreach is essential in order to build credibility and trust around the profession, such that philosophy will be taken seriously by the general public, which is necessary to give philosophers a greater opportunity to contribute to contemporary issues in a constructive way.

It was the resistance to the science of climate change in the 1990s that sparked this realisation, and triggered reflection by the scientific community on previous resistance to outreach (notable rejecting Carl Sagan becoming a fellow of the National Academy of Science). I’ve seen similar resistance by academic philosophers to other “vulgarisers” and popular philosophers.

Yet some still do engage in outreach, and the entire profession benefits. I am seeing a greater awareness of the importance of engaging with the public, but many academics have never been trained in how to do so effectively. As a public philosopher and former journalist myself, I try to help philosophers in Australia to engage with the media or the public wherever possible.

As for whether it should be a fourth pillar of academic philosophy – yes, if it can be made complementary to the other pillars. I can’t speak to the academic culture in the US, but in Australia there are already enough pressures on academics that mandating outreach risks imposing an unsustainable burden.

But one can pursue outreach outside of academia as well, as I have. I work as a full-time public philosopher for The Ethics Centre in Australia – granted that’s a rare role.

I suspect there’s a greater opportunity in learning from science, which created an entirely new discipline of “science communication”. Why not teach people philosophy *and* communication, and train up a cohort to help share the tools and insights of philosophy with the world. We’d need money, and roles for the phil communicators to take, and philosophy doesn’t have the same extra-academic infrastructure & money as science, but I do suspect that good communicators could better sell the value of philosophy.

If anyone’s interested, I wrote about the value of philosophy communication here (some years ago, but it’s still relevant): https://medium.com/so-ethical/why-we-need-philosophy-communication-9b54b7f740a3