Evidence for a Probabilistic Turn in Philosophy (guest post)

“If our data is representative of the philosophy literature, then the use of formal methods in philosophy changed starkly over the course of just a single decade.”

In the following guest post*, Samuel C. Fletcher (University of Minnesota), Joshua Knobe (Yale University), Gregory Wheeler (Frankfurt School of Finance & Management), and Brian Allan Woodcock (University of Minnesota) discuss the findings of their research into relatively recent changes in the use of formal methods by philosophers.

The authors are curious about the causes of this change; discussion is especially welcome on that, as well as on whether the change they describe is related to other relatively recent trends in philosophical thinking and methodology.

[Laura Owens, untitled (2016)]

Evidence for a Probabilistic Turn in Philosophy

by Samuel C. Fletcher, Joshua Knobe,

Gregory Wheeler, and Brian Allan Woodcock

A few decades ago, the use of formal methods in philosophy was dominated by a small number of closely related techniques. Above all, philosophers were concerned with the application of logic. Indeed, to the extent that philosophers turned to other areas for formal tools to conduct their research, it was often to areas that were intimately connected to logic (e.g., set theory).

A question now arises as to whether there has been a change in the use of formal methods in philosophy over time. Is the use of formal methods in philosophy still dominated by logic, or has there been a shift toward diversification, with an increased use of other formal tools? And if so, what other tools?

In a new paper, we report the results of a quantitative study that provides information about this question. We looked at papers from recent years (2015-2019) and compared them to papers from a decade earlier (2005-2009). The aim was to figure out whether the use of formal methods in philosophy has changed over that time period.

To get some information about this question, we picked one specific philosophy journal (Philosophical Studies) and looked at the change over time in the papers within that journal. We coded each paper for whether it used formal methods, and, if so, which formal methods it used (e.g., logic, probability theory), what subdisciplines of philosophy it belonged to (e.g., epistemology, philosophy of language), and the level of complexity of its usage of formal methods. In total, we coded and analyzed approximately 900 papers. (For more detailed information about the methods and statistical analyses, see the paper itself.)

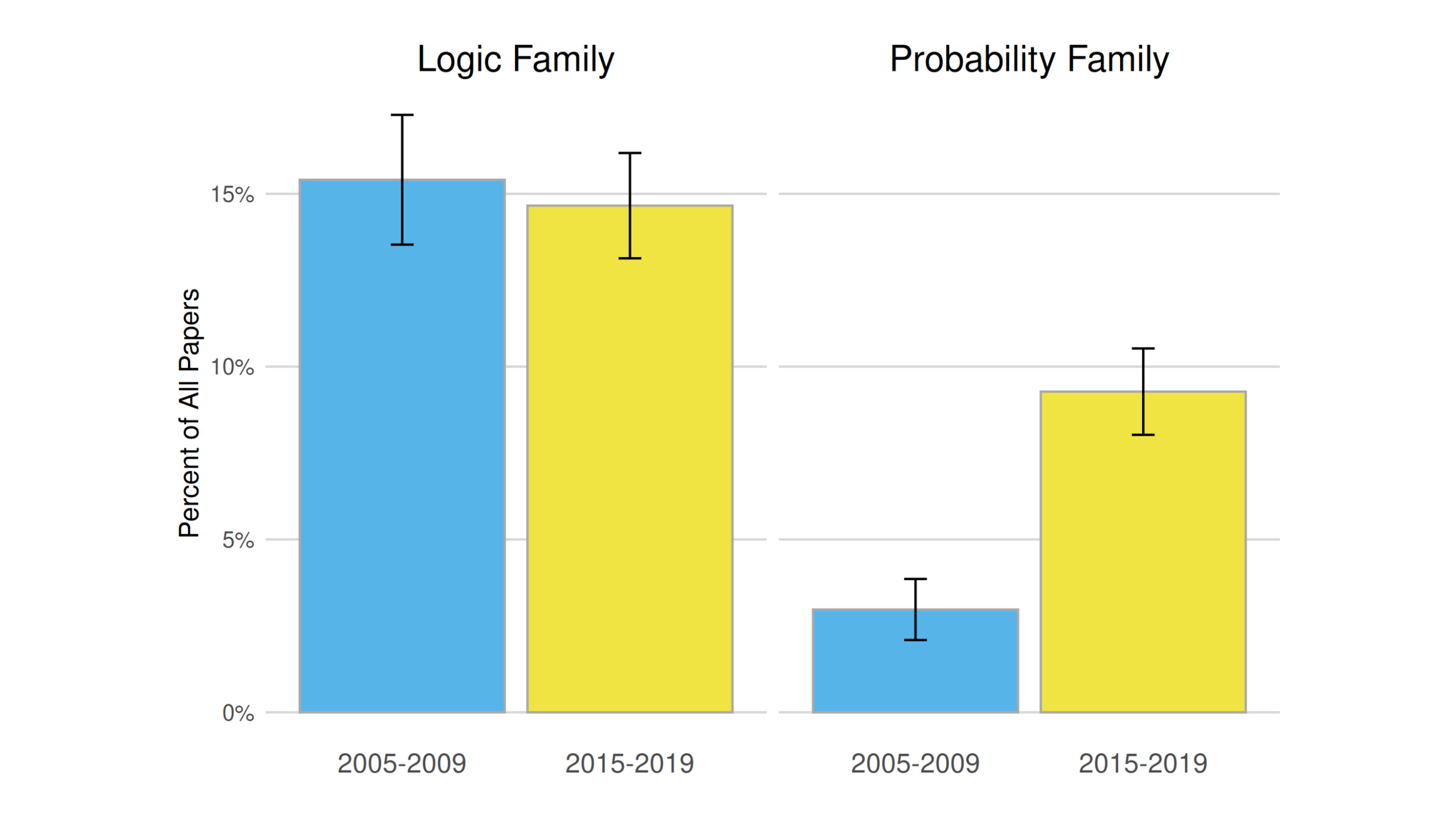

First, we classified the formal methods used in the papers as falling into a number of broad families. On one hand, there was a “logic family” (with logic, modal logic separately, and set theory); on the other, there was a “probability family” (with probability theory, decision and game theory, statistics, and causal modeling). Any given paper could be classified as falling into just one of these families, into both, or into neither.

Here is the change over time from the 2000s to the 2010s within each of the two families:

As the figure shows, the proportion of papers falling into the logic family remained relatively constant over time, but the proportion of papers in the probability family changed dramatically. In the more recent years, there were three times as many papers using probabilistic methods as there were a decade earlier.

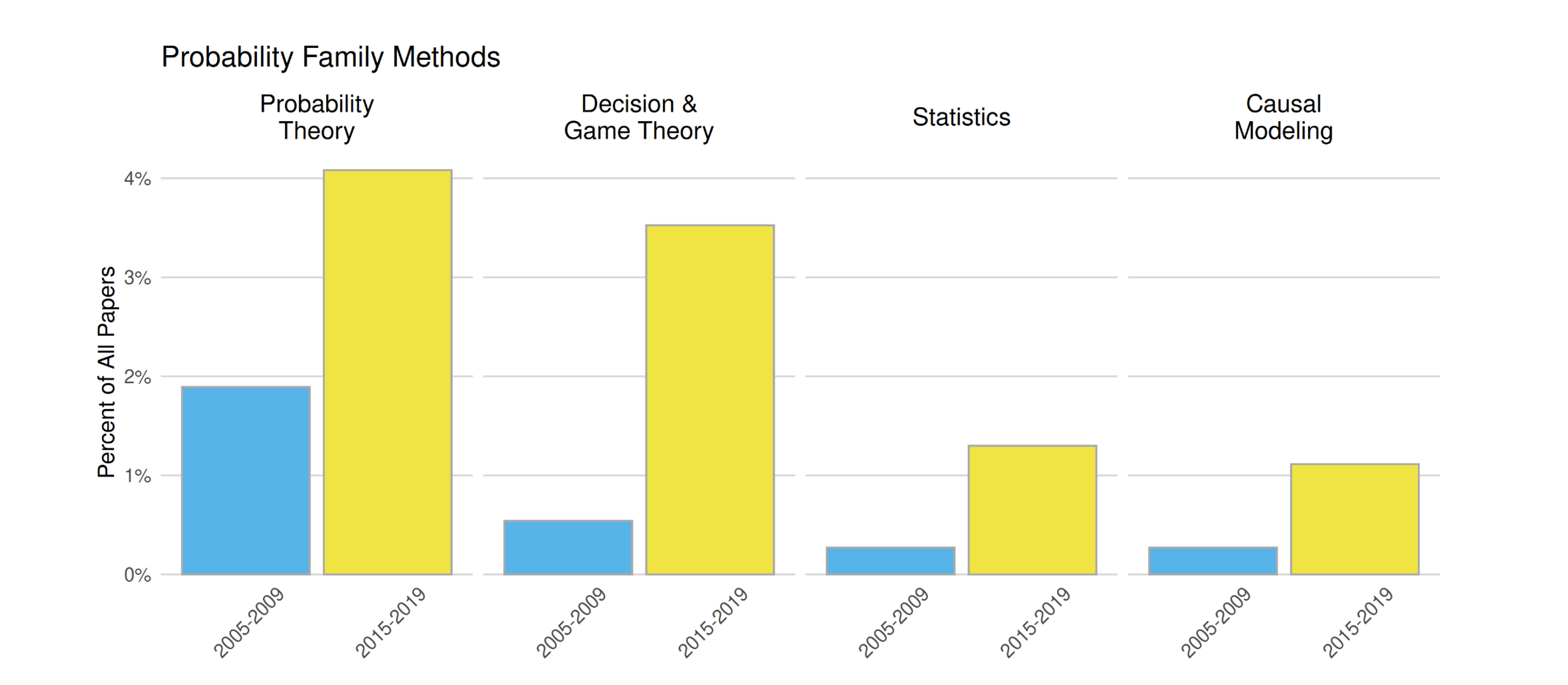

We then broke down the broad probability family into more fine-grained categories to look at different formal methods that make use of probabilities (probability theory, decision theory and game theory, statistics, causal modeling). We looked separately at the change over time for each of these separate methods.

As the figure shows, we find a sharp increase for each of the individual probabilistic methods. Comparing the more recent years to a decade earlier, we find that there is now around six times as much use of decision theory and game theory, five times as much use of statistics, and so forth.

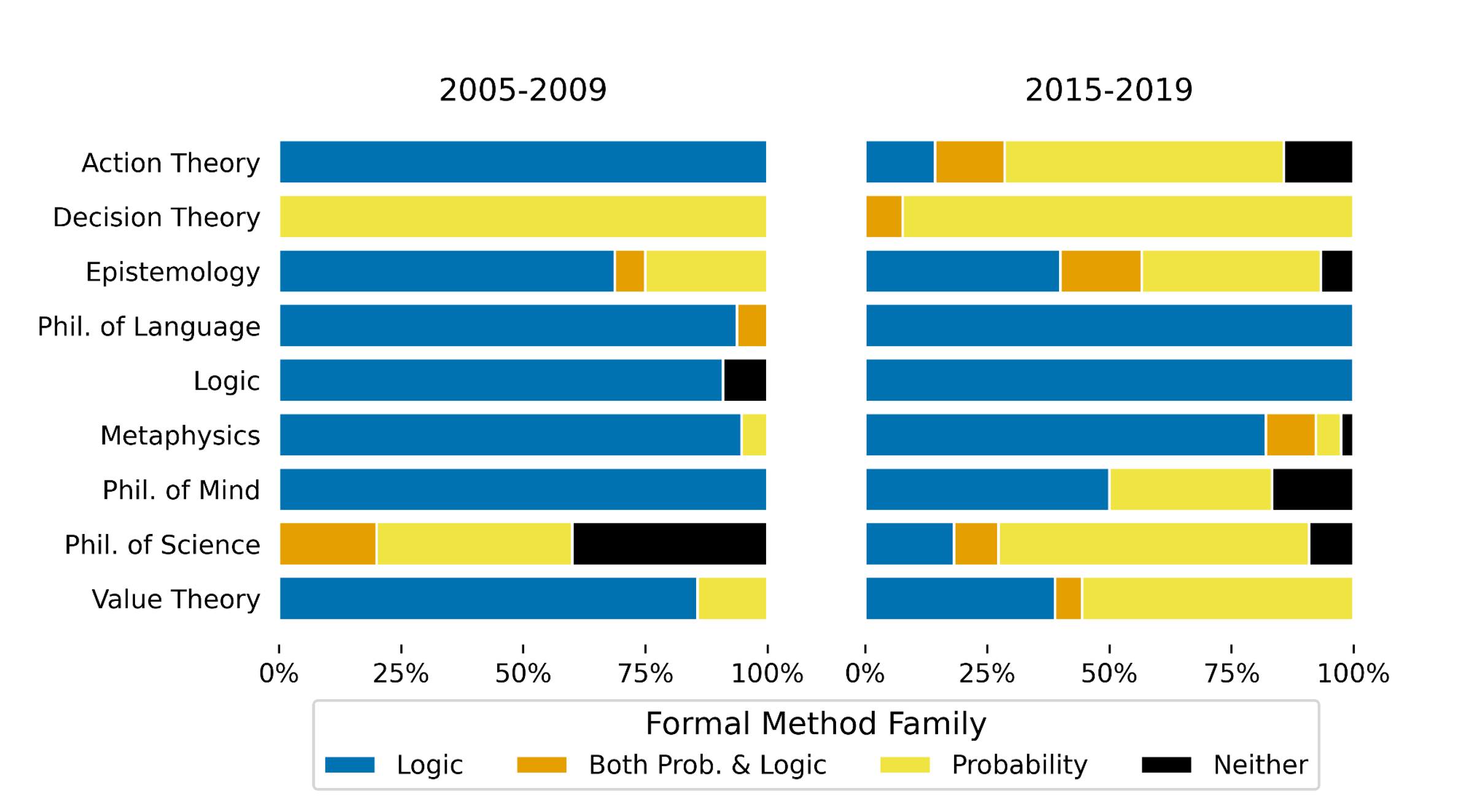

Next, we broke things down in a different way, dividing up the papers by subdisciplines of philosophy. Like with the methods, individual papers could be classified as belonging to more than one subdiscipline. This approach makes it possible to see whether the change over time was driven by one specific subdiscipline (say, just by epistemology) or whether it was more pervasive.

The results indicate that the change (increases jointly in the yellow and orange bars in the figure) was remarkably pervasive. We find an increase in the use of probabilistic methods within epistemology, but we also find an increase in the use of probabilistic methods in action theory, philosophy of mind and value theory. Similarly, when we broke things down by complexity of usage, we found that the increase was ubiquitous, not confined to more or less complex usages.

If our data is representative of the philosophy literature, then the use of formal methods in philosophy changed starkly over the course of just a single decade. This change includes a sharp increase in four different probabilistic methods (probability theory, decision theory and game theory, statistics, causal modeling) across four different subdisciplines (action theory, epistemology, philosophy of mind, value theory). We don’t fully understand why this would be the case and would be interested to hear from readers about why this might be happening.

We also don’t know whether this trend, if it is real, will continue in the decades to come. However, if things were to continue to change at even roughly the pace they seem to have been changing over the past decade, probabilistic methods would soon overtake logic-based methods to become the most frequently used formal methods in the discipline of philosophy.

Neat study! This confirms some trends I’ve been seeing (anecdotally). I would guess that the Formal Epistemology Workshops (and, more generally, the growth of the FEW community) probably has something to do with this. But, of course, I would be expected to say that. 🙂

Only ‘expected’ in the sense of being probable, though. It wasn’t deductively entailed.

exactly.

Hi Branden,

Totally agree that the wonderful FEW community is contributing to this change (and a huge thanks to you for your work on that!), but one thing we find a bit mysterious is that a whole bunch of separate areas of philosophy moved in the same direction at the same time.

So you are right that there has been an explosive growth in formal epistemology over the past decade, but there have also been very sharp increases in causal modeling, experimental philosophy, game theory… all approaches that use probabilistic methods, albeit in very different ways.

Yep — and I see it as part of an even more broad probabilistic turn in scientific inquiry more generally.

I suspect that this could easily be validated, at least in certain areas of science. Artificial intelligence has certainly made a major transition from logic-dominated to probability-dominated (though whether it’s been in this particular decade is less clear to me). My guess is that linguistics would look sort of like philosophy of language here (i.e., still more logic than probability, but an increase in probability – but perhaps the change has been bigger in areas like phonology and phonetics), and economics would look a lot like decision theory here (i.e., already thoroughly probabilified from early on). Psychology would be interesting to see.

I’d expect that core physics/chemistry/biology have had less of a change over the past decade or so.

It might depend on which bit of physics you’re looking at. A lot of physics is fairly insulated against these trends because its experiments are so repeatable (a six-sigma signal is robust against a lot of variation in Bayesian priors). But if you looked at observational cosmology, I suspect you’d see some of the same trends. (LIGO uses a lot of Bayesian modelling, for instance.)

Karen Hao, in a piece for <i>MIT Technology Review</i> that we cite in our paper, looked at the abstracts of all AI papers on arXiv from 1999 to 2019 and found that the move away from logic-based methods to probabilistic methods in AI started in the mid 2000s.

The following graph plots the relative change in the mentions of top keywords over time.

The point of no return for knowledge-based reasoning appears in hindsight to have been 2012, with the introduction of AlexNet.

Hi Branden and Kenny,

Exactly! We make this same point in the paper. It’s hard to know what is causing the change, but at the very least, it seems clear that it isn’t something confined just to philosophy. In this very same time period, we also see a massive shift away from logic and toward probability within computer science, and a shift toward more probabilistic theories within psychology. So, whatever is happening in the discipline of philosophy, it has to be understood as just one part of this larger change.

Nifty!

Given that it’s one journal, this could be the result of an editorial change there. This could be checked partly by just asking the editors. If there was a self-conscious attempt to be more open to probabilistic work, then the upshot of the study is just that it worked.

I’m confused about what’s being shown in the third figure (breakdown by subfield). The first figure indicates than not much more than 25% of papers in the sample use formal methods. But, in the third figure, the majority of papers use formal methods. Maybe this is looking at a subset of only papers that use formal methods? But then there shouldn’t be a “Neither” category.

Hi Dan,

The third figure asks the question: Of all papers that do use formal methods, what proportion use logical methods, and what proportion use probabilistic methods?

The “neither” category is for papers that do use formal methods but use methods that fall into neither the logic family nor the probability family.

Great study. As some others have said above, this parallels developments in other fields.

I suspect that fields like information theory, game theory, and so on will continue to drive this trend. And modeling using agent-based models or other probabilistic simulation techniques will also drive it.

I’m surprised there weren’t any papers involving probabilistic logics. That seems very weird.

Hi Eric,

We were most surprised to see evidence for a probabilistic turn across the board, a point Josh mentioned earlier in this thread. That suggests to us there are multiple drivers that extend beyond the fields of decision & game theory, information theory, or even beyond the philosophy of science more generally.

Is there any sense that this reflects a trend toward pragmatic attitudes if not methodology? Perhaps unintentionally driven with disappointment with lack of progress with armchair philosophy?

We probably should emphasize that these are relative effects that we are reporting and that the majority of papers published in Philosophical Studies over this time are not using formal methods at all.

But among the papers using formal methods, probabilistic methods are growing fast. It would be interesting to assess general changes of attitudes in philosophy and see what effect, if any, changing uses of formal methods might have.

Can anyone link me to some good papers in value theory using probabilistic methods? Curious what this looks like

Hi Edward,

One example from our data set was:

Murray, S., Murray, E. D., Stewart, G., Sinnott-Armstrong, W., & De Brigard, F. (2019). Responsibility for forgetting. Philosophical Studies, 176(5), 1177-1201.

It reports the results of a series of experiments about how people ordinarily understand moral responsibility for forgetting. It uses statistical methods to analyze the results.

To add to Josh’s examples:

Sober’s paper uses probability theory to compare inference-to-the-best-explanation arguments for moral and scientific realism.

Chung uses decision theory to argue for what’s described in the title.

Thanks guys!

Interesting! How many of the papers are xphi? Do they account for most of the ones y’all code as using statistics?

Hi Eddy,

Great question. To get some more information, I checked all of the papers we coded as using statistics.

In total, there were eight papers coded as using statistics. All of them were experimental philosophy papers. Looking just at those, we had one paper in 2005-2009 and seven in 2015-2019 – a very striking increase across just that one decade.

If I might hazard a guess, I would predict that the use of statistics in philosophy will continue to spread. Right now, most of the philosophy papers using statistics might be in experimental philosophy, but I bet that philosophers will start using statistics in other ways pretty soon.

Interesting to see that Philosophy of Language is still “stuck” in logic, given how statistical methods have completely taken over NLP…

First, I am NOT a philosopher in any usual sense of the term. I think of myself as a philosophical journalist. I have a strong background in mathematics and statistics as well as computer science, clinical psychology, mythology, and social psychology. Philosophically speaking I am a mixture of pragmatism, Daoism, and Buddhism and am amazed how Iain McGilchrist has managed to pull such variegated areas of the human experience into a coherent view. My approach to philosophy is to gather together as many facts before I attempt to draw them all together into a unifying philosophical view. There is a major shift in the sciences away from stationary processes to non-stationary process evidenced by the use of agent based modeling based on the view of complex adaptive systems initially developed at the Santa Fe institute. This general view sees the human experience immersed in complex systems that have no underlying probability distribution but is better understood as an evolving system that is “governed” by mixed distributions that philosophically is best described the Buddhist notion of dependence arising. Iain McGilchrist has beautifully described this in his book “The Master and his Emissary”. Genetics and artificial intelligence have already made this shift in perspective. I hope people from the analytic philosophy perspective will see the sophia of this new view.