APA Creates “Beyond the Academy” Online Resources

The American Philosophical Association (APA) has created an online version of its set of resources for those with philosophical training who are seeking employment outside of academia.

“Beyond the Academy” includes data, advice for job seekers, and recommendations for faculty about how to support non-academic career paths. The APA is also holding a webinar on non-academic careers on April 28th. (via Shane Wilkins)

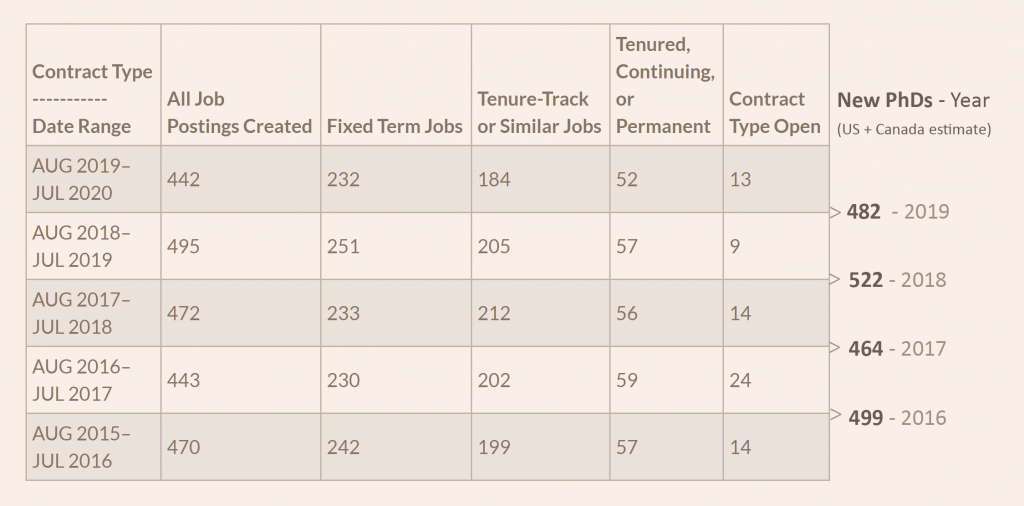

The data on the APA site includes information about the number of philosophy PhDs earned each year and the number of jobs advertised:

The APA notes in its analysis of these figures that “there are enough tenure-track positions in philosophy for about 40% of the doctorates produced in the US and Canada each year.”

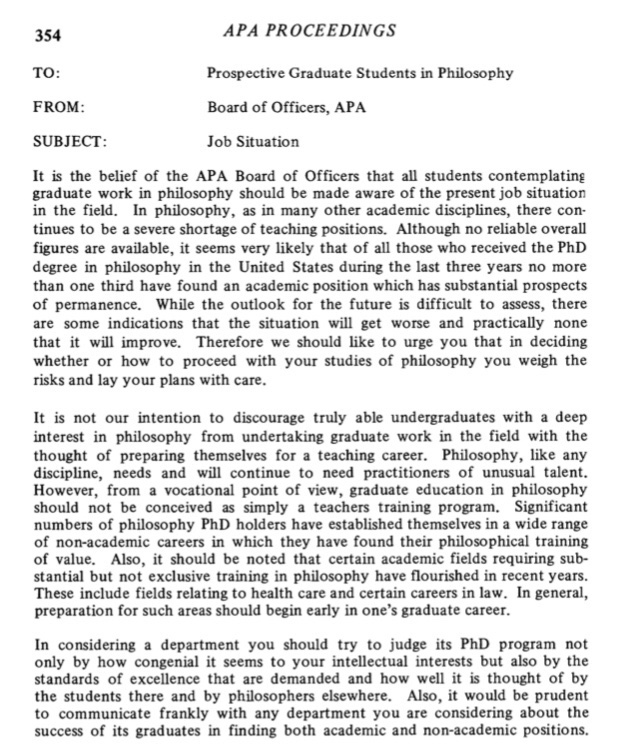

Relatedly, Nathan Ballantyne (Fordham), in his continued look into the history of the APA, recently came across statements from the organization’s Board of Officers from 40 years ago about the job prospects for new PhDs in philosophy. The 1979 statement, below, says, “it seems very likely that of all those who recieved the PhD degree in philosophy in the United States during the last three years no more than one third have found an academic position which has substantial prospects of permanence… [T]here are some indications that the situation will get worse and practically none that it will improve.”

For departmental placement information, consult Academic Placement Data and Analysis and this post.

Does it not in some way overburden students to emphasize non-academic careers rather than discourage departments from over-enrolling or, for “substandard” departments, having a PhD program at all? All this talk focusing on telling graduating students what they might do, and nothing said to departments who keep churning out PhD students who have little to no chance (for a myriad of reasons) of being placed in their chosen profession? It seems to me that producing the amount of PhDs above ill serves the profession just as much as telling them there’s no jobs and they’re better off picking up an MLS and becoming a librarian.

While I’m inclined to agree with the thrust of this comment, I’m also willing to acknowledge that there are good reasons for admitting a surplus of students. For example, sometimes, the students who seem less promising are the most promising, and those who seem most promising are not. For this reason, it does serve the profession to admit so many. There, of course, are other reasons. I need not review them all.

The ratio of philosophy PhDs to decent academic jobs is poor. The relevant question is whether the problem is too many philosophy PhDs or too few decent academic jobs.

I think I agree with you, Tom. But one problem (among many otheras, as Jen alludes to) is that a number of those substandard programs are R1s with faculty who have 2/2 loads and research quotas to meet.

For these programs above the ‘top 25’ (or whatever), I don’t see faculty looking any time soon to pick up another 100-level course each semester, even if it means confronting the moral hazard of admitting graduate students with zero professional prospects.

The system is an extraordinary convoluted ponzi scheme with no one behind the curtain (and therefore no one ‘bad person’ to blame).

*Edited for typos

Currently, academic institutions depend on the work of per-course adjunct instructors, but also don’t pay them livable wages. If we want to deal with the shortage of decent academic jobs, we can either cut down on the number of people getting PhDs, or we can pay instructors more. The first option would either mean increased course loads for professors, or fewer course options for students. The second option would either mean higher tuition or cutting costs elsewhere (the obviously correct answer if we lived in a world which made education about education).

It upsets me when I see philosophers immediately jump to the first option.

I’d be interested in a survey of students who completed PhDs at “substandard” departments to see if they wish they had been denied access to grad school.

I earned my PhD from an unranked philosophy department. Near the end of my studies, I knew that a full-time, tenured position might not be in the cards for me, so I started preparing to teach high school math. I ended up being very lucky and finding a tenure track, low-paying community college job, then moved to another community college, and now I’m in a nice area making six figures teaching philosophy as a tenured professor. Had that not worked out, though, I think I would have been happy as a high school teacher, and I wouldn’t have traded my experience in grad school. It seems presumptuous to make a decision on behalf of people who might not mind completing graduate studies without securing a tenure-track position without, at least, knowing if those students actually regret their decision.

I’m not sure how patterned the responses would be. But in my experience a significant problem in my low-ranked program was that, given today’s insanely competitive market, most of the junior faculty were recruits from brand name programs, and many were un-invested in the graduate students.

No students were really sure why, and I’ve no doubt there were a number of reasons.

But one strong suspicion was that these faculty just didn’t consider us to be on their level, and they were more interested in making tenure than in mentoring.

Do I regret it? Not really. But graduate school wasn’t exactly the dynamic, exciting, community of intellectuals I had dreamed about in my undergrad. We were primarily lowly paid grading labour.

Hi, John.

I’m sorry to hear about your experience with junior faculty at your program. I’ve heard horror stories about even the highest-ranked programs (faculty discord, misogyny, harassment, etc.). I feel very fortunate to have had a very different experience. My department was incredibly supportive of me.

There’s some good evidence, at least from philosophy PhDs at the University of California, that most do not regret earning a PhD, even when they did not go on to get an academic job. Though, UCs are R1, so that might not address your question. As someone currently on the job market, as much as I am dedicated to pursuing research in academia, I will not regret earning a Philosophy PhD if things do not work out for me. The value of the experience is present in nearly every interaction I have in my daily life. I can’t imagine a good substitute – though, this may just be an issue with my imagination.

While it may be true that philosophy, and the humanities in general, overproduce PhDs to some extent, I do take issue with the idea that philosophy departments, especially in lower prestige universities, should substantially decrease the number of PhDs they produce. There are a number of reasons for this. First, although most philosophy PhDs will not find academic employment, many will find gainful employment for which they are well paid. In my experience, folks who leave the academy are quite happy with the decision, even if the decision to leave had more to do with making rent and feeding their families than an desire to leave. One of my undergraduate mentees, with only a philosophy B.A., is currently making 85k+ per year at 5 years out. That’s more than the average tenure track professor. Nothing to sneer at. With the right skill set, a philosophy PhD might be able to earn considerably higher pay as middle management. Maybe. Who knows? We need more data. This does however require training that most PhDs in philosophy are not currently receiving. And this is the emphasis of the Beyond Academia work being done at the APA.

Okay, but its not our chosen profession. Well…let’s be clear, most of us chose to become academics because that’s what we’re prepared to do. I cannot imagine a life without academia, but many people I know dislike most aspects – publishing, teaching, academic politics, and so forth. So, second, it might well turn out that many philosophy PhDs will indeed end up in their chosen professions if we rethink our ideas about what philosophers are meant to do. Most first year graduate students have no idea what it means to be a serious academic researcher, and I think many PhDs in the humanities pursue academic jobs because they just don’t know what the other options are. In this light, it might turn out that we’re underproducing PhDs for careers we just don’t know about yet. Maybe. Who knows? We need better data on this. Regardless, we should be seriously worried when we say that the profession of a philosopher is a full time academic job when only 40% of professionally trained philosophers are tenure track professors. Most philosophers do something else, and many might even want to do that other work if they knew it was a possibility. (It seems bizarre to assume that the bulk of the philosophical community has somehow been relegated to lives of misery and dissatisfaction because they didn’t get the job that we all already pretty much knew they weren’t going to get.)

Third (and most important), it is extremely difficult for folks who lack substantial academic capital to gain entry into more prestigious programs. While earning a degree of any sort can assist with ending cycles of generational poverty, earning a PhD will help ensure that significant academic capital will be transferred to the next generation. And, at least for the recent history of the academy, more prestigious programs seem to lag when it comes to considerations of social equity more generally. For example, until recently the most prestigious philosophy programs (overall) have had the lowest numbers and proportions of women faculty and graduate students (compared to less prestigious programs). So, curtailing the number of PhDs granted at less prestigious programs will probably also obstruct some of the most important pipelines for social equity in the discipline, though this is just a hypothesis.

There are plenty of other reasons, but these seemed most pressing. Its not all sunshine and rainbows, but the situations does not need to be as bad as it is. And the solution is probably not to just put an end to the surplus of philosophy PhDs. We need to come by the means to effectively redirect our extremely well-qualified, intelligent, and talented PhDs, from programs at all levels of prestige, into other careers. And we need to move faster to serve the members of our community who are currently suffering in this job market. These are the pressing issues that this Daily Nous post and the APA are contending with.