The Philosophy Profession, Mid-20th Century

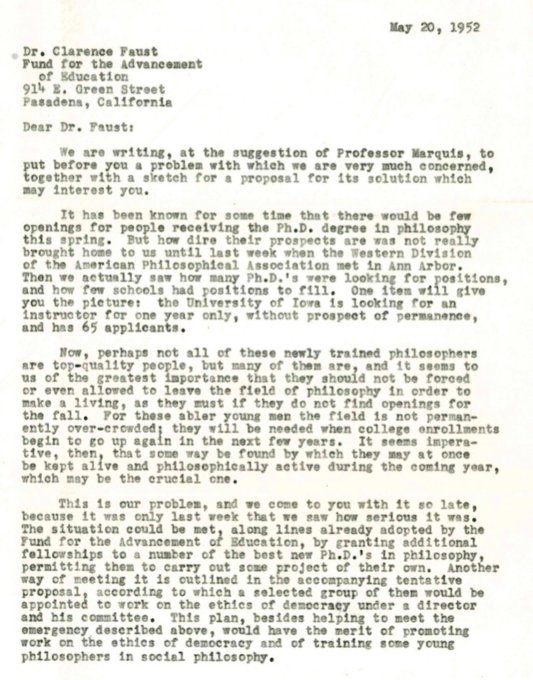

It has been known for some time that there would be few openings for people receiving their Ph.D. degree in philosophy this spring. But how dire their prospects are was not really brought home to us until last week when the Western Division of the American Philosophical Association met in Ann Arbor.

Then we actually saw how many Ph.D.’s were looking for positions, and how few schools had positions to fill. One item will give you the picture: the University of Iowa is looking for an instructor for one year only, without prospect of permanence, and has 65 applicants.

That’s an excerpt from a letter from University of Michigan philosophy professors William Frankena and Paul Henle, dated May 20, 1952, to the Ford Foundation, seeking last-minute funding to create 12 post-docs for some of the philosophy Ph.D.’s who weren’t going to be hired by any school that year. They continue:

Now, perhaps not all of these newly trained philosophers are top-quality people, but may of them are, and it seems to us of the greatest importance that they should not be forced or even allowed to leave the field of philosophy in order to make a living, as they must do if they do not find openings for the fall. For these abler young men the field is not permanently over-crowded; they will be needed when college enrollments begin to go up again in the next few years. It seems imperative, then, that some way be found by which they may at once be kept alive and philosophically active during the coming year, which may be the crucial one.

The letter was unearthed by Nathan Ballantyne (Fordham), who posted it on Twitter over the weekend:

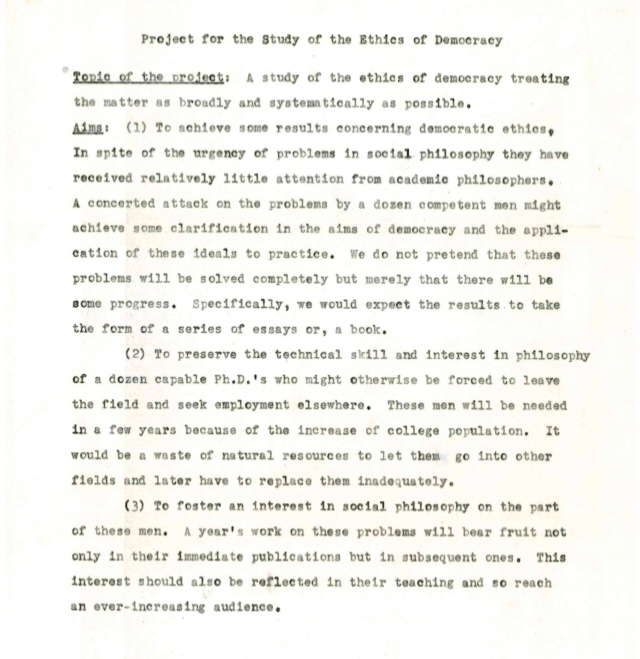

In the funding proposal, Frankena and Henle write of the unemployed philosophers that “it would be a waste of natural resources to let them go into other fields and later have to replace them inadequately.” So they suggest post-doctoral fellowships on the subject of “The Ethics of Democracy”:

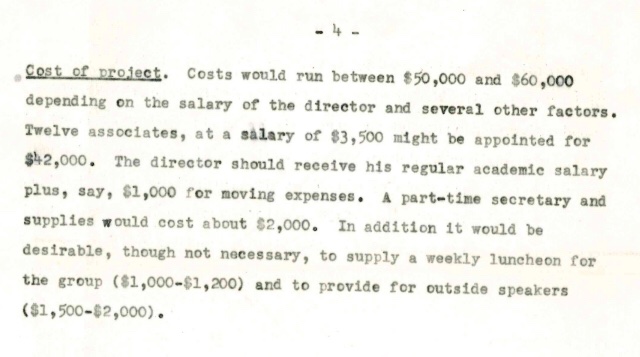

Each fellow would earn $3,500:

In today’s dollars that’s just under $35,000.

This is just one document among several that Dr. Ballantyne has been collecting for a project of his.

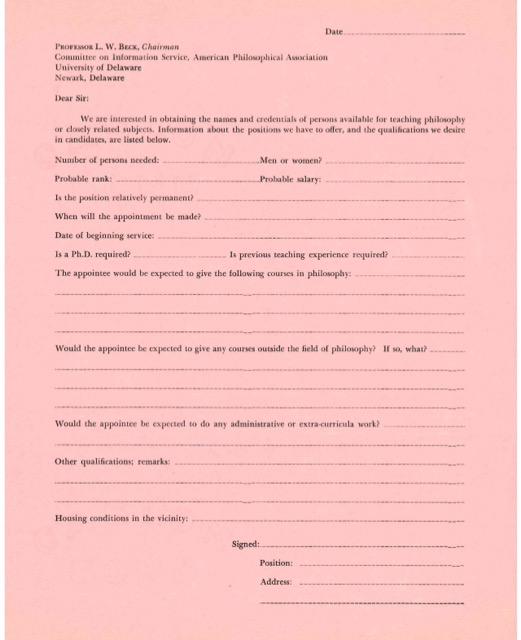

Another recent find was a form produced by the American Philosophical Association’s Committee on Information Service around that time by which philosophy departments could make their hiring needs known to the association:

Note the question, “Man or Woman?” Dr. Ballantyne found the text of a 1953 talk by Lewis Hahn, chair of the APA’s placement committee, apparently summarizing information gathered over recent years through this form. Most departments, he says, “prefer that the candidate be a man”:

Note, too, the “fairly often” requests for breadth of interests “rather than narrowly specialized or technical interests” and the importance of “the social significance” of philosophy over “a high degree of technical proficiency.”

To bring these two documents together, I wonder how many of the dozen folks who would have gotten the fellowships would have been women… (I assume the application was unsuccessful. If successful, it’d be fascinating to see know the names of the fellows.)

As a female student in my first year of Philosophy studies, I’m also VERY curious

We have too many PHD Philosophy Programs giving students false hope. We could probably eliminate half of them and still have a surplus of job seekers for the limited number of academic positions that are open.

Exactly. Across the humanities PhD spectrum there is often attention given to the demand side (how many positions available – basically none) but less on supply. Focusing on supply would highlight the extent universities are complicit in this problem in that they are churning out way too many PhD every year. But if they dramatically cut back on PhD admissions or God forbid instituted a near moratorium on them it would be suicide for their programs. Its kind of a death spiral.

For a different take on this, see “Against Reducing The Number of Philosophy PhDs“

When I was adjuncting I was getting offered 8-10 classes a semester in departments covering 3/4 classes with adjuncts. Seems to me that the most urgent issue is exploitative conditions on the demand side, where they’ve figured out that some of us will slog for a bit because we are mission driven rather than financially driven. Let’s fix the demand side before we start telling people that they cannot share the transformative experience of intensive, discipline-specific, study and obtaining of mastery. If I hadn’t gotten lucky with a ft position, I’d have adjuncted a bit then probably taught high school math. We should be honest in advising undergrads, but talk of closing programs is self defeating nonsense.

There are opportunities in the writing profession since Philosophers are writers.

I am a writer since my PhD took me nowhere. Now I can write a series of short stories about poverty and loss called “Nowhere”, inspired by Simone Weil and María Zambrano, nobody and everybody reads in IInstagram. Seriously I’d found this post very interesting. I’m spanish, living in the underworld of the spanish underworld, where philosophers are women who are thinkers and, at the very end, poets, all of them.

Pretty fascinating post. I’ll add in my own contribution with some remarks.

Many years ago due to the retirement of a senior colleague I came in possession of a folder containing the mimeo minutes of the entire 10-year run of a committee in the UW–Madison philosophy department, beginning in 1952. The charge of the committee was to examine the content and methodology of teaching their Introduction course (first 1a, later 1, today 101). The membership of the committee across those years alone constitutes quite an interesting assortment of faculty and, in its late stages, several lecturers: Marcus Singer, Cornelius Golightly (the first African-American philosopher at Madison as far as my research shows), Robert Ammerman, Carl Bogholt, William Goodwin, E.F. Kaelin, Julius Weinberg, Haskell Fain, and Fred Dretske, among others. No women members.

What struck me after writing an 8000 word commentary on the minutes is that many contemporary concerns about teaching undergraduates are echoed there: students are underprepared, do not read closely or well, write poorly, do not reason logically, etc. The minutes collectively also reveal many problems that current members of academic committees might nod in recognition: meandering discussions, failure to move efficiently through agendas, lack of progress on major issues, returning to the same topics after (sometimes years after) covering them before, the sometimes deleterious effects of replacing members of a multi-year committee, you know all too well! But the committee wasn’t a total failure either, as Singer argued in his foreword to the collected minutes written in 1964. Original discussions of what students need to know in the introductory course that were driven by faculty spit-ball-guessing about their students’ interests and beliefs finally emerged into an empirical survey in the late 50s that in turn resulted in an Inquiry article about student attitudes and beliefs–arguably one of the earliest uses of what we now call X-Phi (Fain was an important catalyst to all this). The minutes also contain the survey and the article itself. While even in ’64 it’s apparent that some participants questioned the survey’s methodology, it was still pretty groundbreaking.

I scanned and enhanced all the pages (Singer’s original foreword was not legible without that enhancement, for example) into jpg, wrote the commentary, and sent it all including the originals to Professor Harry Brighouse at Madison, feeling that it really belongs to their departmental heritage. I knew Harry from his generously allowing me to participate in some activities of his Center for Ethics in Education, and he seemed very interested in saving this legacy. I understand that he might have had the entire collection of jpgs transcribed–a pretty daunting task considering it was over 60 images.

So here is one case of history being rescued by chance–I wonder how many other departments disposed of interesting historical documents thinking them just more paper taking up file cabinet space.

Interesting!

In the late 1960s, I graduated with a degree in Philosophy. The schools I requested applications from sent them along with a caveat that there were to

be few jobs in the field. And so it was on to law school.

As an aside, at one law school where I had an interview, the interviewer actually told me that Philosophy has little relevance to the study of law. I weighed whether that was a provocation or just stupidity.

My main reaction is admiration for Frankena and Henle for an altruistic effort, even if unsuccessful, to benefit recent philosophy PhDs, and not just their own, whom they saw in an unfortunate situation. And was the ethics of democracy topic an attempt to appeal to cold war sentiments on the part of the granting agency? Even if it was it’s obviously an important and still relevant topic.

— I agree, Tom, and not just admiration for the altruistic effort, but also for the ability to see a solution beyond the constraints of typical institutional arrangements and common practices, and the spirit to try for it.

I had that reaction, too, Tom. In poking around old papers, I’ve come across some interesting efforts by established philosophers to help young philosophers and job seekers. And, surprisingly to me, philosophers were involved in all sorts of grant work during the Cold War, with the Ford Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, etc. When you read articles by mid-20th century philosophers, they rarely mention support received from foundations, but that was part of the story.

Why the ethics of democracy? I’m not sure, but it would certainly fit into the Ford Foundation’s priorities around then. In 1951, the FF kicked off a program called the Fund for the Advancement of Education, and that’s the funding stream that Frankena and Henle were trying to dip into. By 1957, this initiative had flooded $40 million into different projects, most of which had to do with “the improvement of teaching”. That’s $40M in 1957 dollars. (Adjusted for 2021 dollars, that is around $400M.)

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1292303?seq=1

Can the APA ask each one of Apple, Google, Amazon, Netflix, Facebook, Tesla, etc., to start a foundation aimed at studying the ethical use of technology, the improvement of democracy, the improvement of education, the alleviation of poverty, and perhaps some other things? Then can the APA ask for lots of jobs for philosophers to be funded by these newly created foundations? If Frankena and Henle took a shot with the Ford Foundation in 1952, why can’t we take a shot with the Fords of today?* Mark Zuckerberg needs some good press, since his press has been terrible since the 2016 election. So, maybe try Facebook first. Really, it’s a win-win. Facebook gets good press. We get jobs.

*I realize the Ford Foundation already existed in 1952, whereas my proposal is that the APA should ask Apple, Google, etc., to start new foundations. But still…