Junior Yearly Progress Reports in Pandemic Times

A junior faculty member has questions about the assessment of faculty on the tenure-track over the past year, particularly regarding how such faculty should, if at all, discuss how the challenges of the pandemic affected their progress.

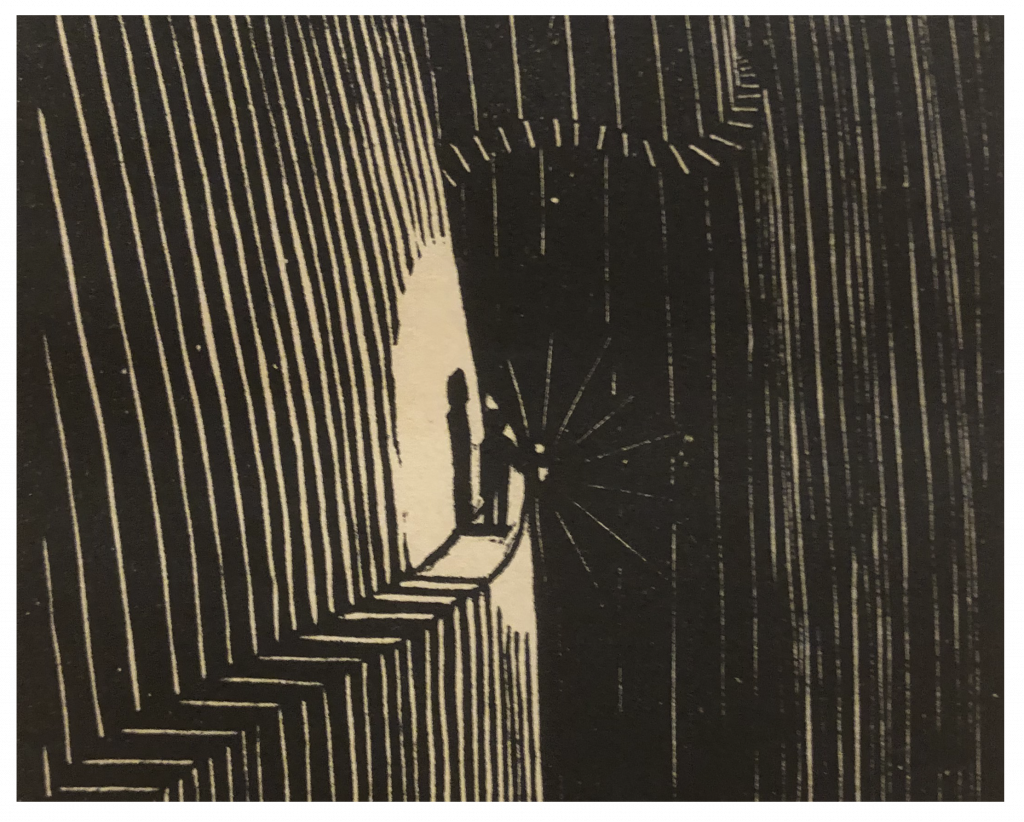

[M.C. Escher, “Never Think Before You Act, La Pensée, from Flor de Pascua” (detail)]

They write:

Lots of junior folks are working on or will soon file our yearly progress reports (and in some cases, have meetings about them). How should we be thinking about the function of these documents and meetings, this year? Normally, these files and meetings are meant to work as incremental check-ins to ensure that we are on track toward earning tenure.

Obviously “normal progress” was impossible for most of us this year, whether or not we had children at home. Still, even when it’s true, it feels infelicitous to say something like “it took all my effort to stay on top of teaching/mentoring/supporting people more vulnerable than me, so I didn’t make much/any progress on the conferencing/publishing/etc. dimension this year” to someone who is probably juggling twice as much work. And of course junior academics are keenly aware of the importance of continuing to be viewed as productive, energetic scholars, and so are reasonably wary that being too honest about the difficulties of this past year will be damaging in the long term.

So… any thoughts on how to approach or think about what’s adequate progress vis-a-vis these kinds of reports, this year, compared to a normal year? What’s the bar for ‘good enough’? What’s a sign for concern? Does that even apply this year?

Your comments are welcome. In sharing your thoughts about these questions, it might also be useful to note whether your institution has made any official announcements or policy changes relevant to them.

This is not quite directly responsive to the original question, but I worry that even if the acute effects of the global shutdowns are largely mitigated by the end of 2021, its opportunity-constricting effects will continue to be felt for a good 3-4 years after, while the various institutions that make up higher-ed are struggling to recover financially.

Conferences will likely be slow to start back up. Funding for extra speakers, travel, or leave will be hard to get. Academic presses will be more selective about book contracts. Journal acceptance rates will stay low, because it will keep being hard to find referees. Graduate students will be facing challenges than usual in the past, and so faculty who care about their well-being will sink a higher proportion of their time and energy into helping them make progress. Generally, the amount of effort and skill it takes to secure the usual indicators of research productivity will be much higher for the next several years than it had been for the previous several.

It’s well and good to say “this year doesn’t count”, but if we’re still thinking about the bar for tenure as largely unchanged, or relative to cohort-group performance, junior faculty with their eye on these kinds of costs should be worried. For some large number of junior faculty, their entire remaining tenure clock will elapse before the normal expectations for a “tenurable file” are reasonable to have.

There’s been a lot of conversation about how to avoid losing a generation of scholars; what I’ve seen has been (appropriately) centered on academics facing the job market. But it’s worth having a conversation about how to think about slow-burn problem for junior faculty: if tenure evaluation standards remain continuous with the past, we might well lose a number of people currently in their second or third year on the tenure track.

This is my concern too. My personal situation is exacerbated by having spent 2019 on maternity leave, meaning there was nothing in the pipeline to come out in 2020. 2020 has also been a wash (toddler, no childcare), so it’s going to be 2022 or later before any work comes out from me.

I think one palliative to this would be to have serious conversations with your chair and dean now, to make sure they know about these situations and will take them properly into account. Seed the ground now to harvest later, as one might say. It might be possible to pause or extend the tenure clock (probably it did pause for your leave?) and then this becomes less of an issue.

My view is that a frank, realistic assessment is always best. If teaching online took up huge amounts of time, if the pandemic and related issues made it impossible to do research, and opportunities like conferences dried up–and OF COURSE they did–then those things should be mentioned in annual evaluations and tenure files. Those aren’t excuses, they are just the way the world is. We can’t pretend we aren’t human or that the profession is somehow immune to external reality.

As a senior member of my department and chair of our evaluation committee, I plan to be as flexible and generous with my part-time and junior colleagues as I have been with my students. This year has been hard enough, there is no reason to add to that with unreasonable evaluations. I hope and expect that others elsewhere will take similar approaches.