Some Good News, Some Bad News in the APA’s State of the Profession Report (guest post)

The American Philosophical Association (APA) today released a new report, “State of the Profession 1967-2017 and Beyond: Institutions and Faculty.”

The report, drafted by Debra Nails (Michigan State University, emeritus) and John Davenport (Fordham University), “gives a detailed picture of the profession of academic philosophy—that is, the makeup of philosophy departments and philosophy faculty in North America—and how it has evolved over five decades.”

Its information comes from past editions of the Directory of American Philosophers published by the Philosophy Documentation Center (PDC) and other data from the PDC, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the APA, and departmental sites.

The report, its authors say, “provides more detail on the state of the profession than has previously been available, including more specific information on gender, institutional types and affiliations, and regional differences among philosophy programs” and “explores the types of institutions that teach ad hoc courses and those that offer degrees, identifying where faculty in contingent positions are most concentrated, and where women philosophers are most concentrated.” It also provides information on the types of positions philosophy professors hold.

The full report is available here. In the following guest post*, Carolyn Dicey Jennings (UC Merced) and Eric Schwitzgebel (UC Riverside) cover some of its key findings.

Some Good News, Some Bad News in the APA’s State of the Profession Report

by Carolyn Dicey Jennings and Eric Schwitzgebel

We were recently provided with a report from the APA that recounts work by Debra Nails and John Davenport to collect, organize, and analyze available data on the discipline over the past 50 years, including data from the Philosophy Documentation Center, the National Center for Education Statistics, and the APA itself. We are grateful for the efforts of Nails and Davenport in creating this important report on the state of the profession. As colleagues on the Data Task Force, we have some insider knowledge of how challenging this task was, and how much time it required between 2016 and now. In reviewing the report, a few threads stood out: good news, bad news, and supporting news. Let’s start with the good.

Contingent Faculty

While some use the language of “adjunct” or “part-time” faculty, we follow the report in using “contingent,” since it is possible for adjunct and part-time positions to be permanent ones. The national issue of increasing contingent labor in academia has come up many times at the APA Blog and Daily Nous, and there was recently an APA session dedicated to the topic. As one report puts the problem:

For many part-time faculty, contingent employment goes hand-in-hand with being marginalized within the faculty. It is not uncommon for part-time faculty to learn which, if any, classes they are teaching just weeks or days before a semester begins. Their access to orientation, professional development, administrative and technology support, office space, and accommodations for meeting with students typically is limited, unclear, or inconsistent. Moreover, part-time faculty have infrequent opportunities to interact with peers about teaching and learning. Perhaps most concerning, they rarely are included in important campus discussions about the kinds of change needed to improve student learning, academic progress, and college completion. Thus, institutions’ interactions with part-time faculty result in a profound incongruity: Colleges depend on part-time faculty to educate more than half of their students, yet they do not fully embrace these faculty members. Because of this disconnect, contingency can have consequences that negatively affect student engagement and learning.

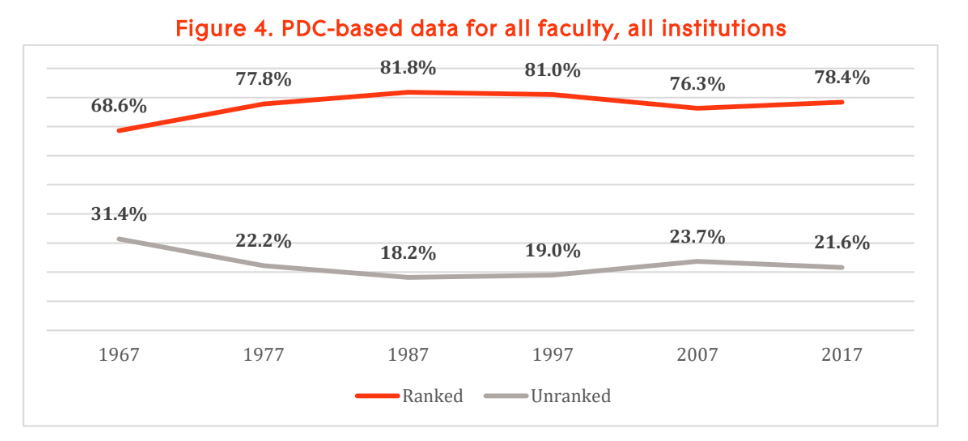

So far this sounds like bad news, but we want to be sure that we do not overlook the real issues contingent faculty face in communicating the good. Namely, that the percentage of contingent faculty in philosophy is low and stable. As Nails and Davenport explain, around 73% of all faculty nationwide are in contingent or “unranked” positions, whereas only 22% of philosophy faculty had contingent positions in 2017. Moreover, there is a lower percentage of contingent philosophy faculty now than there was in the 1960s. While the APA membership numbers have suggested this for some time (with around 20% of its members reporting contingent status), a reasonable concern about that estimate was that contingent faculty might be underrepresented among APA members. This new report suggests that the numbers just are low in our discipline. That’s good news, under the plausible assumption that it is best for the discipline if a large majority of faculty are tenured or tenure track.

While we are heartened by these findings, we see a couple of reasons to stay vigilant about the status of contingent faculty.

First, we don’t know the reason that there are fewer contingent faculty in philosophy. It may be, for example, that philosophers are less likely to teach the types of courses that are typically offered to contingent faculty, such as general education and writing courses. In that case, this wouldn’t be a reason to celebrate philosophy’s success on the issue.

Second, the report raises the possibility that contingent positions have recently been replacing assistant professor positions: “Since 1987, there has been a steady increase in the number of faculty hired outside the tenure system compared to entry-level positions inside it.” We note only that the numbers show that the ratio of assistant professor positions to contingent positions has shifted from about 1:1 in 1987 to about 4:3 in 2017, representing a gain of about 500 contingent positions while the number of assistant professor positions remains about the same (see “a” in Figure 5).

It is unclear what we should conclude from this, since the overall ratio of contingent to non-contingent faculty hasn’t really changed: there are also nearly 500 extra professor and associate professor positions since 1987 (“b” in Figure 5). This could be due to faculty staying in the profession for longer than in past decades, but it could be for some other reason. Zooming in on the difference between 2007 and 2017, Nails and Davenport note that “the drop in assistant professors and rise in associate professors may indicate a decline in entry-level hires since 2007. Universities that hired new faculty into contingent positions in the wake of the Great Recession have not yet made tenure lines available to those who, under normal circumstances, would have been hired as assistant professors.” But here, too, the additional numbers of those in associate and professor positions could explain the difference (“c” in Figure 5). It may be, for example, that those in more recent years are achieving promotion faster than in past years, leaving fewer people at the assistant rank relative to ranked positions, overall. So it is unclear what to take from this data, but we may want to be cautious, given the possibility Nails and Davenport raise.

Alright, how about some bad news?

Decline

The bad news is that philosophy is represented at about 100 fewer institutions in 2017 than in 1967 (1669 colleges and universities in 1967 and 1552 in 2017). This appears to represent a decline of the discipline in academia that has been the subject of numerous blog posts.

Surprisingly, the report particularly notes a decline in philosophy at (non-Catholic) religious institutions, both at the undergraduate and graduate level. Whereas around 16% of all public institutions offer no philosophy degree, this is true of 27% of non-Catholic religious institutions (but only 11% of Catholic colleges and universities). We don’t know the root of this decline of philosophy in religious institutions. It might be due to the especially atheistic culture of philosophy and its writings, or due to such institutions having comparatively stronger religious studies or theology programs competing for majors, or due to the relatively left-wing politics of many academic philosophers.

In addition, a striking 78% of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCU) offer no philosophy degree. Given the historical racism in philosophy, it seems likely that this is also connected to cultural issues. It would be in the interest of philosophy to further explore the matter. (Interested readers might start with this interview with Brandon Horgan at Howard University, an HBCU.)

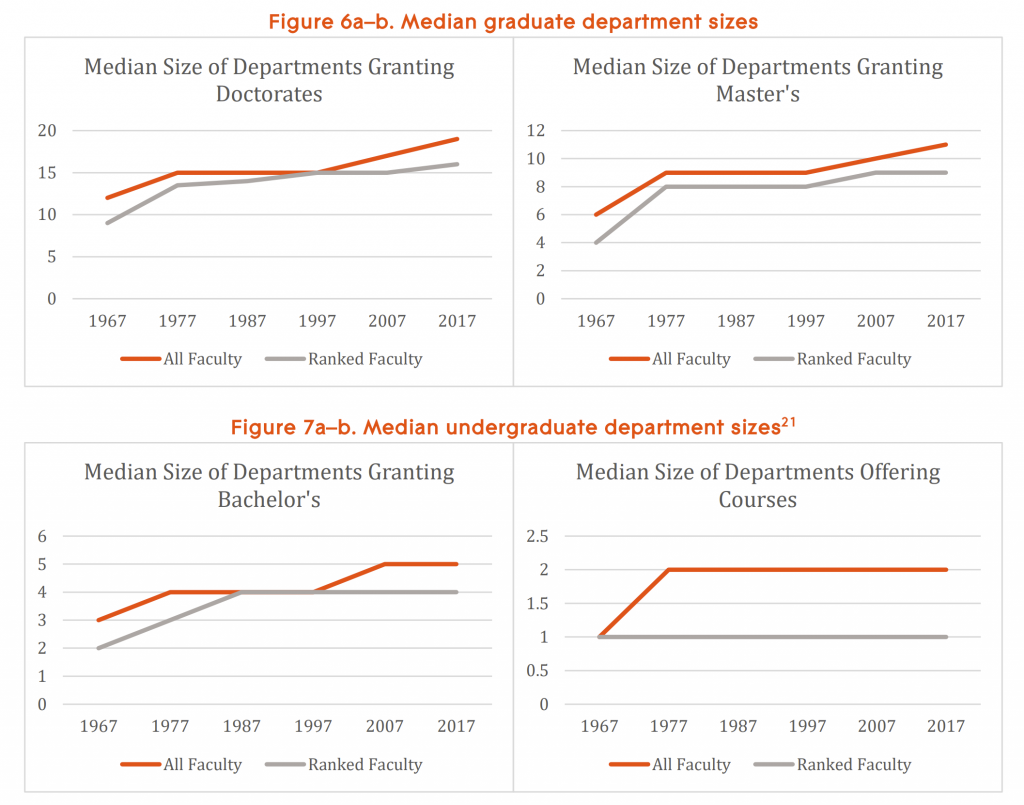

We did note one reason for optimism with the overall numbers: while the numbers of institutions with a degree in philosophy has declined, the number of faculty at these institutions has increased, from around 6,000 in 1967 to around 9,000 in 2017. One can see how this played out at most institutions through the median number of faculty: whereas the median number of faculty for programs offering a PhD in philosophy was around 13 in 1967, it was around 19 in 2017. Similarly, those offering a Master’s went from 6 to 11, those offering Bachelor’s went from 3 to 5, and those offering courses only went from 1 to 2 (Figures 6a-b and 7a-b).

The report also provided some numbers that support other findings, which we called “supporting news” above. We focus here on the supporting news regarding gender diversity. (The authors of the report were unable to explore race/ethnicity, disability, LBGTQ status, or other aspects of diversity.)

Gender Diversity

The APA now collects some demographic data from its members, including gender, race/ethnicity, LGBT status, and disability status. Among the 1874 APA members who reported gender, 505 (27%) answered “female”, 1363 (73%) answered “male”, and 6 (<1%) answered “something else.” Other recent research has suggested that women constitute about 30% of recent philosophy PhDs and new assistant professors in the U.S., about 20% of full professors, and about 25% of philosophy faculty overall (plus or minus a few percentage points). However, most of this previous research is either a decade out of date or is limited to possibly unrepresentative samples, such as APA member respondents, faculty at PhD-granting programs, or recent PhDs.

The current report finds generally similar numbers, in a larger and more representative sample (all faculty in the Directory of American Philosophers from 2017). Overall, 26% of philosophy faculty were women, including 34% of assistant professors and 21% of full professors. (Associate professors and contingent faculty are intermediate at 28% and 26%, respectively.)

We note that the authors of the report relied on the DAP’s binary gender classifications of faculty, which were generally reported by department heads or other department staff. And where faculty gender was not specified, the report’s authors searched websites and CVs for gender designations. Thus, the data do not include non-binary gender and some classification errors are possible.

The tendency for women to be a smaller percentage of full professors than assistant professors could reflect either a cohort effect, a tendency for women to advance more slowly up the ranks than men, or a tendency for women to exit the profession at higher rates than men. On the possibility of a cohort effect, since professors often teach into their 70s, the lower percentage of women among professors might to some extent reflect the fact that in the 1970s and 1980s, 17% and 22% of philosophy PhDs in the U.S. were awarded to women. By the 1990s, it was 27%, which is closer to the numbers for recent graduates. However, cohort effects might not be a complete explanation, since 21% might be a bit on the low side for a group that should reflect a mix of people who earned their PhDs from approximately the 1970s through the early 2000s. In the NSF data, women received 23% of all philosophy PhDs from the year 1973 through 2003—the approximate pool for full professors in 2017.

The report also explores gender by institution type, highest degree offered, and region. One notable result is that philosophy departments offering at least Bachelor’s degrees had on average higher percentages of women than departments not offering Bachelor’s degrees. Faculty were 27% women in departments offering the PhD, 28% in departments offering a Master’s but no PhD, 27% in departments offering a Bachelor’s degree, 22% in departments offering a minor but no Bachelor’s, 23% in departments offering an Associate degree but no minor, and 20% in departments offering philosophy courses but no degrees. (A chi-square test shows that this is unlikely to be statistical chance: 2×6 chi-square = 24.3, p < .001, lowest expected cell count = 104.) We are unsure what would explain this phenomenon.

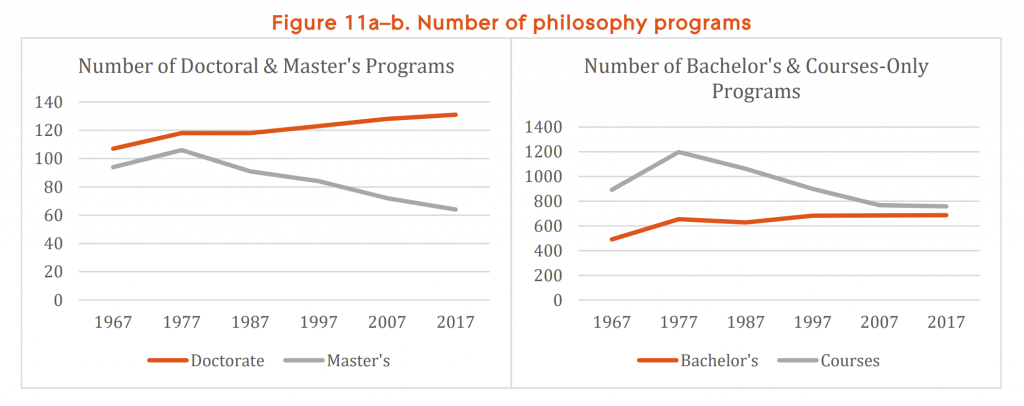

Editorial note: readers may also be interested in the report’s data concering the number of graduate and undergraduate programs in philosophy, represented in Figures 11a and 11b, below. Nails and Davenport write, “the total number of doctoral programs has continued its slow increase since 2007, despite the soft job market for faculty positions in the tenure system.”

“But here, too, the additional numbers of those in associate and professor positions could explain the difference (“c” in Figure 5). It may be, for example, that those in more recent years are achieving promotion faster than in past years, leaving fewer people at the assistant rank relative to ranked positions, overall. So it is unclear what to take from this data, but we may want to be cautious, given the possibility Nails and Davenport raise.”

I’m a bit surprised by this claim that it is unclear what to take from the data. It seems to me that the decline in the ratio of assistant professors to other faculty (TT and otherwise) is pretty alarming. Just the raw number of Assistant professors, at under 1500, is pretty alarming on its own. The APDA’s data suggests that, in the 5 years leading up to 2017 (2011-2016), there were 3,391 PhDs granted in philosophy ). While some of people may have been promoted early, we also know that some people move laterally and spend more than 5 years as assistant professors (I would bet the number who do this is far larger than those who get early promotions, but that’s just based on anecdata). There are also folks who take postdocs (seemingly more of them than there used to be, though that is again anecdotal). Both these populations should make up for those with early promotion.

). While some of people may have been promoted early, we also know that some people move laterally and spend more than 5 years as assistant professors (I would bet the number who do this is far larger than those who get early promotions, but that’s just based on anecdata). There are also folks who take postdocs (seemingly more of them than there used to be, though that is again anecdotal). Both these populations should make up for those with early promotion.

So the decline seems alarming, but so too do the raw numbers. And all of this was before the present catastrophe. The take away here seems very clear to me.

My claim about “both populations” making up for the early promotion is a mistake, sorry. The postdoc population is just relevant to evaluating how bad the job market is in any given year.

I agree that yours is probably the most obvious interpretation, and it fits with how Nails and Davenport the situation. However, given that the overall ratio hasn’t changed much and the surge in Associate Professors, I think some caution is warranted.

I don’t want to put Carolyn on the hook for this interpretation, but one possibility is that there was a (comparative) surge in hiring circa 2000-2007, which shows itself as a bulge in the associate rank as of 2017, and that post 2008 hiring is a higher ratio of contingent to tenure stream than pre 2008.

PS: I should have posted this as a reply to Postdoc10.

Re: Contingent faculty. Are contingent faculty counts including only “adjuncts” (people who are paid by-the-courses) or do they include all faculty employed outside of the tenure-track (perhaps as a separate question, do they include graduate students teaching their own courses)?

I’ll be honest and admit that across the three universities I’ve worked at the ratio of non-tenure track faculty instructors to tenure-stream instructors was always *at least* 1-1. In the large cash-strapped R-2 I spent some time at, the ration was more like 1:3 (tenure-stream : non-tenure stream) so either my experience is highly unusual (not impossible!) or the APA’s data just isn’t’ very reliable at giving us a picture of the profession (as opposed to its members).

Graduate students were not included in the contingents count. Setting that issue aside, I agree that it’s plausible that contingent faculty are disproportionately undercounted in the DAP, and that job titles vary confusingly from place to place.

>job titles vary confusingly from place to place

This is definitely the case at my current university where there are four different non tenure-stream ranks (two kinds of adjuncts and two kinds of lecturers) which are not promotionally defined. One doesn’t begin at the lowest rank and progress upwards, we just have four different terms denoting, roughly, how long one’s contracts last (one term, one year, three years, six years) and how much service and non-teaching is expected. I assume that we’re not alone in that sense either.

Also, are you counting heads, or full-time equivalents? That would make a big difference to the ratios between tenured and contingent, I imagine.

The institutions at which the faculty is less female (institutions without any degrees in philosophy) are also the ones where the median number of faculty is 2. It would be interesting to see if there’s a correlation between gender representation and total number of faculty at the institution. I would not be surprised if somehow implicit bias about what a philosopher “should” look like is a bigger effect at an institution hiring their only faculty member or their second, than at an institution that has a dozen faculty in the field already. It’s possible that this explains why gender ratio is so different at these institutions without degree programs (my conjecture would suggest that the few among them with large departments would have gender ratios more in line with those at degree-granting institutions).

Interesting thought, Kenny!

Thanks for the analysis by Carolyn and Eric, and the interesting comments that follow. Just a few things to note.

(1) It was a huge disappointment for me to realize, a few months into this in 2017, that we were not going to be able to deeply assess full-time vs part-time, and tenure-stream vs non-TT positions, because we cannot infer these with certainty from job titles. We could make some approximations from the PDC data, but did not have enough self-reported statuses from individuals (e.g. from APA data) to categorize each person listed at each institution into a definite job status such as tenure stream. This is one of the main reasons that a complete survey of departments and programs really must be done next time (in 2027).

(2) Of course the lack of data by race / ethnicity is another big limit. Another reason for a survey next time.

(3) A survey would also allow us to look into info from institutions not reporting to the PDC. For all its great work, and invaluable data shared with us, the PDC cannot chase down non-reporting institutions forever. If we had info on individuals teaching philosophy at from more colleges and universities that are members of big associations, such as the CIC or Historically Black colleges and universities — a lot of which did not report — what would we find? What if there are several hundred community colleges at which someone is teaching a few philosophy courses, but the PDC did not have their data in 2013? With all that info, we might find more contingent faculty — or people with degrees in English or Religion or something else teaching philosophy.

(4) IMHO, we could also better assess the faculty numbers over time if we also had data on numbers of students enrolled in Arts & Sciences colleges. For example, what if one could track a 15% increase in students in these colleges (as opposed to Nursing or Business etc.) in a 20 year period in a given region or big state (like CA) but then see only a 10% increase in Philosophy faculty (or 8% in TT faculty) in that same period and region? (Obviously I just made up these figures for sake of illustration). We would somehow have to factor in philosophy courses taught outside A&S programs, but the bigger problem is that universities report total numbers. I’m not sure how one could find figures on (say) just the A&S student numbers at universities — unless one looked up 1600 some websites, which we did not have staff to do. So we can only use changes in total 4-year and 2-year college enrollments as a comparison point relative to faculty numbers.

(5) Sad to say, universities just seem to report grad student numbers too irregularly and unreliably to the PDC. We had the same problem with some job titles like “postdoc,” which can also mean different things at different places.

(6) These problems give you a taste of the obstacles we faced (no fault of the PDC though; this is just the nature of what institutions have reported). There are still more analyses that could be done with the refined and aggregated data in our spreadsheet — for example, correlation between gender representation and total faculty numbers would be possible. Without staff, it would have taken too long to do more analyses, and we wanted to finish them by the end of 2019 so the info did not get too old to be useful.

All this said, I still feel like a novice at this kind of work — both at statistical analysis and finding data sources. Debra Nails is the real expert, and she is the reason this report exists. So take everything I say with a grain of salt.

PS to Caligula’s Goat, it also seems possible to me that some large depts just have not been reporting all their contingent faculty to the PDC, although this may improve over time as the importance of contingent faculty is increasingly respected.