Now May Be The Time To Transition to Tutorial Instruction (guest post)

The pandemic and the various disruptions it is causing to the operation of academic institutions has prompted people to reflect on the value and qualities of those institutions. This guest post*, by Preston Stovall, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Hradec Králové in the Czech Republic, is one example of this.

In this post, he suggests we see the massive move to online teaching as an opportunity to introduce tutorial-style teaching in philosophy in places like the United States, where it is much less common.

On the Possibility of Transitioning Toward Tutorial Instruction at U.S. Philosophy Departments

by Preston Stovall

In thinking about the way the COVID-19 pandemic might impact philosophy departments in the future, I want to draw attention to four interrelated concerns: 1) that the quality of the education students will receive during this period may decline owing to the transition to online education; 2) that after this is over universities may take this opportunity to switch to more online courses; 3) that in doing so this may have a winnowing effect on faculty and decrease the number of lecturing employees; and 4) that this will exacerbate the problems faced by graduate students and recent Ph.D.’s competing in an already difficult market. These concerns are interrelated on account of the possibility of addressing them all at once.

For it may be possible that some philosophy departments, at least for some of their courses, to use this shift into online instruction to transition into some kind of tutorial system as a trial-run during this period. Under the tutorial system students attend a regular lecture once a week, and in addition they meet once a week with a lecturer, sometimes individually and sometimes with one or two other students. Prior to that meeting the students will have written a short essay that is passed around beforehand, and the meeting is devoted to discussing these essays in the context of the course readings and prior meetings. Successive readings and essays develop out of these discussions, with the result that the writing and reflection students undertake during a course is largely driven by their own interests and pace with the lecturer.

The number of students in a given course are going to constrain the feasibility of such a proposal, and surely only some courses would be fit to make this move. If we got serious about this it might help to reach out to people at Oxford or Cambridge, where tutorials are common, and get some advice, and at any rate maybe a limited pilot program would be the way to go. Some universities are transitioning to all-online teaching for summer courses, and so it may be possible to organize pilot programs for that period.

Courses for which this is feasible could setup a google calendar and students could vary from session to session, easing the burden for students to meet at a set time each week. This would be something like a directed study setup, but less stringent. In the U.S. we tend to look at directed studies as instruction-intensive courses for upper-level undergraduates, but if we could get the numbers right we might treat other undergraduate work in a more relaxed but similar sort of way.

It is possible to piecemeal address the four concerns outlined above—quality of online instruction during the quarantine period, universities using this period to transition more to online instruction after the quarantine is over, the resulting decline in lecturer positions, and the impact this will have on graduate students and recent graduates. For instance, a number of suggestions have been made to help foster good practices for online teaching (e.g. an APA webinar on teaching online, a Dischord channel for professional support, suggestions for running interactive philosophy classes online by Alex Hyun and Scott Wisor, a “bare bones” guide for transitioning to online courses during the coronavirus crisis by Gregory B. Sadler, and some recommendations from Matt Deaton, who has been teaching philosophy entirely online since 2013.) A handful of discussions have also cropped up about the impact this transition is likely to have on faculty and graduate students (e.g here, here, and here). Finally, philosophers might collectively organize in the attempt to minimize any deleterious long-term consequences of this shift to online instruction.

On the other hand, a transition to a tutorial-based system has the potential to address all four concerns at once. This sort of system would directly address the first concern owing to the fact that the quality of teaching in the tutorial system is pretty good, focused as it is on small-group discussion and personalized and immediate feedback. I don’t know of any data that directly bears on this, but we might get some of the more social-scientific folks in philosophy departments to do rough-and-ready studies of the impact of tutorial teaching for the proposed pilot programs as against courses that are not taught in this way. I think this move would also address the third and fourth concerns, because you need a fairly large group of lecturers to make this work and that would mitigate the impact of decreasing lecturer positions. Finally, if the tutorial system really is as good or better than the lecture-based method, while at the same time we get to keep or even enlarge our pool of instructors, then perhaps this addresses the second concern as well: for who cares whether the University uses this event as an opportunity to transition more toward online courses if this would be the result?

Perhaps the most difficult issue with this sort of transition, setting aside logistics and institutional inertia, is funding. With more lecturers you need more money, and maybe this would not be financially feasible at most universities. But things seem to be shaping up such that governments across Europe and North America are going to give cash to citizens in order to weather the quarantine. Perhaps universities in a position to do so could use some of their endowments to provide temporary support for their lecturers as programs of this sort are given test runs (assuming the stock market doesn’t gut endowments). If this was done in the right way, one might hope that noblesse oblige on the part of American capitalists would help replenish the endowments.

In good pragmatist fashion we could think of this as an experiment in trying to recalibrate the university organism to an ever-changing environment. For times of instability are times of opportunity as well. As Dewey puts the point:

Life itself consists of phases in which the organism falls out of step with the march of surrounding things and then recovers unison with it—either through effort or by some happy chance. And, in a growing life, the recovery is never mere return to a prior state, for it is enriched by the state of disparity and resistance through which it has successfully passed….Life grows when a temporary falling out is a transition to a more extensive balance of the energies of the organism with those of the conditions under which it lives.

(From p.12-13 of Art as Experience. New York:

Perigree, 1980 (originally published in 1934).

Vol.10 of Later Works of John Dewey, 1925-1953.)

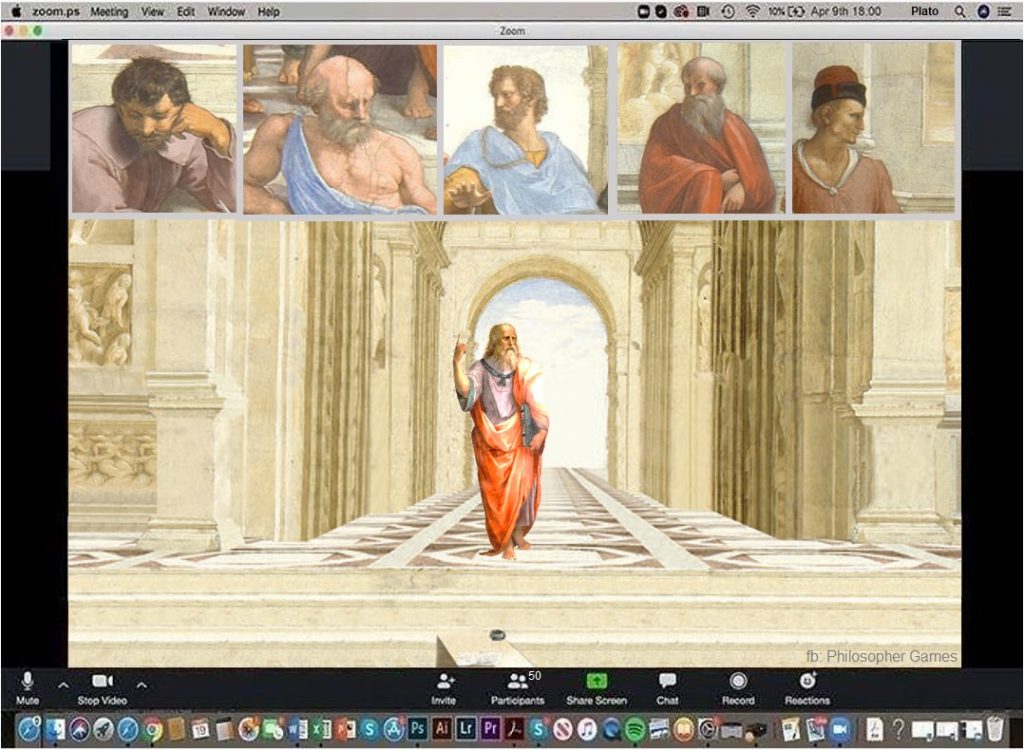

Are we sure Plato would have a MacBook?

If I may, I should like to say that Stovall’s assessment of the strengths of tutorial instruction is spot on. In my experience, students learn immensely well from being instructed in a tutorial, and, from my perspective as a teacher, I have always found the format rewarding.

Woolf University, where I teach, and which recently was founded by academics at Oxford and Cambridge, carries out its instruction on the Oxford tutorial model. Highly motivated students, who are coming to grips with the shifting terrain in higher education, are encouraged to learn more about us. All the Fellows at Ambrose College (with the few exceptions of those from Harvard) have extensive experience tutorial teaching at Oxford or Cambridge.

I’ve taught a lot in both systems. The discussion so far omits a major difference: the means of assessment. Oxbridge students are nearly entirely assessed in terms of exams that are either at the end of a year, but sometimes at the end of their entire degree. These exams are graded by people who are typically not the tutors, and the graded happens after regular teaching has been over for a while (as one does not teach during the examination period). The term-time workload for Oxbridge tutors is already immense, and much greater than their counterparts have in the US. If you add extra term-time grading on top, I think it would be extremely demanding. However, I suspect that US institutions would find it hard to move to the end of year examining model.

Also, I suspect I’m not alone in feeling that the Oxbridge workload was made bearable by the quality and engagement of the students. It is a very long hour of discussion when you tutor a student who isn’t taking the work seriously…

I would also add that part of the success of a well-functioning Oxbridge tutorial model is the expectations that students place on each other about what they are going to do each week. Initially, these expectations will be missing in any transition. So insofar as this is being proposed as a short-term initiative, I would not expect similar results to those achieved in the current Oxbridge model.

I would also hate sitting with an unengaged singleton for an hour. Reinstating tutorial groups of 8-10 students (how University tutorials used to be in Australia, rather than an unmanageable 30 students, as they often are now) strikes me as a happy medium between that and the current system.

Thanks for these thoughts everyone. This was a spitballing idea so I appreciate getting input on some of the difficulties it would face. A couple of quick responses.

First, I think we should be willing to try some evaluation methods other than final exams. I spent a year at St. Peter’s College at Oxford after finishing my B.A., and in my case I didn’t take exams–the essays I’d written for the tutorials were the only basis of evaluation. Something like that seems reasonable to try in the U.S.

But I’ll cop to the charge that under any method of evaluation this is likely to increase the workload, and Happy Medium’s proposal to use the Australian method of 8-10 students in a tutorial might be a way of working around that.

Finally, I agree that the prospect of sitting with unengaged students for an hour is pretty uninviting. It would be important to do as much as we could to institute a culture where students would be expected to meaningfully participate. But the idea is to start with limited pilot programs, and toward that end we might hand select students, or advertise the course in such a way that the expectations were clear at the outset. At the same time I have no trouble telling students who aren’t putting enough work into their assignments that they need to start doing so, and in my experience students are appreciative of that forthrightness and change their behavior as a result. So maybe there’s room to expect that our students would rise to the challenge.

I taught in the tutorial system for eleven years, and I think it’s wonderful – but it is really expensive. Bluntly, I don’t think there is a hope in hell of convincing an institution to do any such thing in the throes of a once-in-a-century economic crisis.

In particular, I don’t think the OP’s funding proposal – spend down the endowment, then fundraise to build it back up again – would be approved by a university’s financial team at the best of times – it breaks the principle that you should spend the income from the endowment but protect its value. But right now would be a catastrophic time to do it, given it would mean selling stock in the middle of a crash.

FWIW I don’t think the issue of grading is too serious. If you wanted to teach tutorial-style for a US course, you’d be setting and commenting on weekly essays in any case. Just grade them and use those grades. (Oxford doesn’t do that, and there are good educational reasons for their approach, but those reasons are mostly independent of the reasons for the tutorial system.)

As it happens, David, the grading method you propose in your last paragraph is the one we use. Its potential disadvantages compared to the marking system used for exams at Oxford notwithstanding, I think it works very well, just as you imagined that it might.