The “PC College Students vs. Free Speech” Narrative is Baloney

Overall public support for free speech is rising over time, not falling. People on the political right are less supportive of free speech than people on the left. College graduates are more supportive than non-graduates.

That’s a summary of recent data by Matthew Yglesias at Vox.

Among the various findings:- public support for free expression has been generally rising

- college students are less likely than the overall population to support restrictions on speech on campus

- there is little age polarization on matters of free speech (e.g., 56 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds support the right of the racist to give a speech, versus 60 percent of the overall population.)

- data from the College Senior Study appears to show a causal relationship between attending college and more open-mindedness

- there’s no evidence that left-wing politics is producing closed-minded people

One exception to the pro-free-speech trend concerns people’s views of whether a “Muslim clergyman who preaches hatred of the United States” should be allowed to speak. Most Americans say the clergyman should not be allowed to speak.

As I’ve often mentioned, commentators are quick to take a few cases of genuinely egregious anti-free-speech behavior by college students and imagine that there is some huge cultural shift going on regarding free speech (see availability heuristic).

Yglesias comments:

The overall debate about “political correctness” as a phenomenon tends to suffer from an excess of vagueness and ambiguity.

On the one hand, there is a fairly narrow debate about the attempted use of heckler’s veto tactics on a handful of college campuses — often in response to speaking invitations that appear to have been constructed primarily for the purpose of attracting hecklers. On the other hand, there is a fairly broad debate about a wide array of anti-racist activity that includes everything from the #OscarSoWhite hashtag to people being mean on Twitter to Bari Weiss to efforts to push the boundaries of who can be described as a “white supremacist.”

By rhetorically lumping in instances of rare, fairly extreme behavior with much more common behaviors under the broad heading of “political correctness,” it is easy to paint an alarming picture of the hecklers as a leading edge of an increasingly authoritarian political culture.

The fact that there does not appear to be any such trend—and that public desire to stymie free expression is concentrated in the working class and targeted primarily at Muslims—ought to prompt a reevaluation of the significance of on-campus dustups and perhaps greater attention to the specific contexts in which they arise.

The whole article is here.

Related: “Tough Enough: Resilience in Academia“, “Are We Being Chilled or Should We Just Chill?”

There is no racism problem in America because 70% of Americans say that they are not prejudiced towards other races.

Two points:

(a) Look at the trends: there appears to be more and more support for free speech

(b) Understand the dialectic: this post (and Yglesias’s article) are a response to claims that things, free-speech-wise, are worse at, or because of, higher education.

There appears to be more and more people who respond positively to questions about free speech. How much does that matter if there is an anti-speech minority that is growing in intensity and are not opposed in any sort of way in action? Things may very well be worse on campuses (or particularly campuses, at least) even with growing verbal support for free speech.

Good point. It is certainty possible for society as a whole to become more tolerant of speech they don’t like and yet for there to be less free speech in society because there are more fringe activist groups trying to police speech who are using bolder tactics than in the past and thus having more success. However, do you have an evidence that this is actually the case? Justin makes a good point that anecdotal evidence is weak, especially given things like the availability heuristic. Do you have anything better?

It’s a good question what would count as evidence for or against this. Do the incidents at various schools in which speakers have been disrupted, cancelled, or physically harassed count as evidence? Does the debacle at Evergreen St. or the Linsday Shepherd incident count as evidence? And we’d have to determine why those incidents took place. Are they homegrown incidents as a result of local, idiosyncratic campus culture, or are they the result of a more widespread movement that manifests itself in such places? I don’t think people dispute (although maybe they do) that more incidents like these are happening than 10 years ago (but maybe not more than the early 90’s or the early 70’s). The related questions are why they are happening, is it a trend that may grow or will fizzle, should there be administrative pushback or acquiescence, and so on. This, of course, assumes that these incidents considered in themselves are bad: that no platforming is bad and free speech is good, etc. Ultimately, the evidence that Yglesias presents simply isn’t relevant to that particular hypothesis.

Did events like the ones you mention take place in previous decades or not? I’m no scholar of the history of universities, but I do seem to recall hearing about some disruptions and occupations of universities in the ’60s and ’70s, and I seem to recall discussion of related issues in the ’80s and ’90s. Without details, I can’t yet tell whether the events of the past five years are of a different character or quantity.

Who is going top admit they are a racist? What a dumb conclusion and comment. Hitler wasn’t a racist in his mind, just a pro-Nordic warrior.

I think the problem–which isn’t as bad as the outrage-mongers on the right-wing like to pretend it is, but still, a problem–is that people who aren’t really racist (or fascist, sexist, etc.) receive that label. So while “support for free speech” across categories might be growing, the number of people lumped into a category for whom that right is denied is also growing.

That’s why groups show up to try shouting down CH Sommers or Ben Shapiro. Yglesias acknowledges that the boundaries of “white supremacy”, for instance, are being shifted. I’m not certain just *how* rare this is–which isn’t to say I necessarily think it common, but I have been surprised by just what some students consider to be sexist or racist.

At the very least, it isn’t something covered by the data in Yglesias’ report and to say that support for free speech is growing because support for the above categories has grown seems, perhaps, disingenuous.

“people who aren’t really racist (or fascist, sexist, etc.) receive that label…. That’s why groups show up to try shouting down CH Sommers or Ben Shapiro.”

Shapiro defended a ridiculously racist video published on his website (before backtracking under pressure)–I’ve seen the video and the description was accurate. I understand if you don’t think that his weird obsession with taking down the Black Panther movie counts as racist but this was definitely racist.

As for Sommers, she appeared on a white supremacist podcast and apparently didn’t say anything to push back against what the host was saying. (I haven’t listened to this myself.) She also advertised her appearance on the same side as the white supremacist and all-around garbage person Milo Yiannopoulos, and was an enthusiastic participant in GamerGate–a movement whose members harassed and issued death threats to feminists for speaking out.

If there’s a problem here, it’s not that Shapiro and Sommers are unfairly being labeled racist.

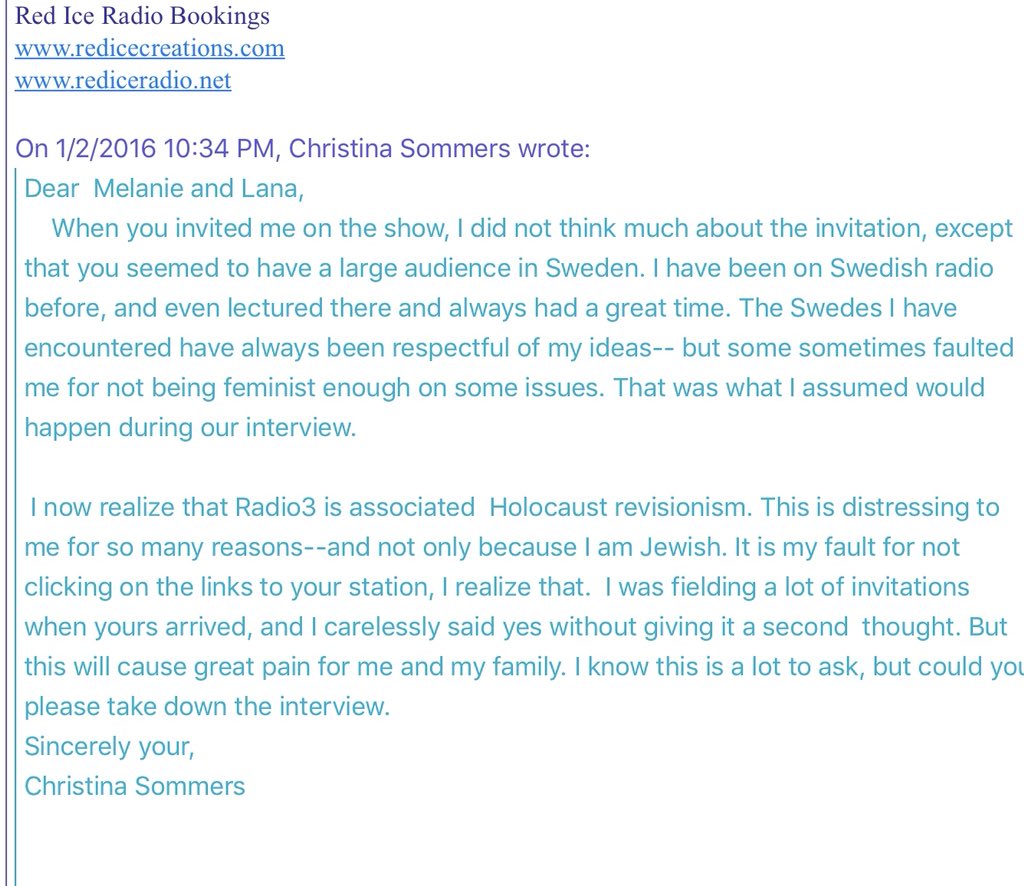

First, Sommers’ alleged leniency with this white supremacy podcast is only being talked now, years after the podcast, as people try to dig deep to try to justify their claims. Even assuming this leniency was there, it can’t explain why students protested against her before (ditto for her relationship with Milo, it didn’t begin there). Second, she did speak against the podcast once she realized what it was about, and that was even before it was released (1);

Honestly, those seem like post-hoc rationalisations of the belief that they hate her ant that she’s a modern day Mussolini of some sort (which is ridiculous).

‘

(1) :large

:large

Yes, who among us has not gone on a podcast with white supremacists, nodded quietly while they said racist things, and then asked for them not to release the episode when we realized how bad we were going to look?

This is precisely the broad labeling I’m referencing. The DailyWire video was crass, tasteless, never should have been posted and Shapiro should not have defended its posting. Columbus did lots of horrible things for horrible reasons. But while the video has racial overtones, it isn’t racist as such–at no point does it indicate indigenous peoples behaved in the portrayed barbaric manners because of their race. It’s a 40 second animated video which simplistically portrays history stupidly. But I don’t think it indicates any causality whatsoever, which I would say is necessary for something to be racist (e.g., “X is inferior because of X’s race”).

Lambaste the video, by all means, lambaste Shapiro for defending it; but do so without broadening the confines of what constitutes racism, or risk enervating the term.

Yiannopoulos is indeed a garbage person. I’ve associated with garbage people before i knew they were garbage. I’ve even given some of those garbage people second chances. Maybe I’m naive, or was. Maybe Sommers is, or was, as well.

And Sommers did indeed appear on a white supremacist podcast… which she tried to prevent being published (as Pedro showed), and asked to have removed. And GamerGate is, I think, the poster-child event for people not knowing how to behave on the internet; i.e., a total clustercuss of baiting statements and wild unfounded allegations instigated by overblown reactions to false statements, in which just about everyone involved said or did something stupid. Personally, I think Sommers stepped in it there; but the guilt-by-association is… well… continuing the kind of bad faith argumentation that GamerGate itself exemplified.

“But I don’t think it indicates any causality whatsoever, which I would say is necessary for something to be racist (e.g., “X is inferior because of X’s race”).”

Yes, if your definition of racism excludes a video that depicts Native Americans as simple-minded cannibals, you will find people labeling a lot of things as racist that you do not consider racist.

“Yiannopoulos is indeed a garbage person. I’ve associated with garbage people before i knew they were garbage. I’ve even given some of those garbage people second chances. Maybe I’m naive, or was. Maybe Sommers is, or was, as well.”

The degree of naivete you have to ascribe to Sommers here is more insulting than anything I could say about her. She was around Yiannapoulos enough to know exactly who he was.

You’re correct: there *are* lots of things people label racist that I do not consider racist. If someone made a cartoon video depicting Carthaginians eating babies, Jews steamrolling Palestinians, Japanese raping Koreans, or Europeans as genocidal colonialists, I wouldn’t consider it racist. I’d consider it a series of tasteless false generalizations; but the race happens to be incidental. In other words: there can be negative portrayals of people of any color which need not be racist. “Japanese and hating Koreans” is not the same as “Japanese _therefore_ hating Koreans”.

Both wrong; but different kinds of wrong. Sometimes, a “therefore” is implied in the “and”, to be sure. But not always; and I think philosophers most of all are obliged to make the distinction.

And secondly, I’m sure nobody truly intelligent has ever misjudged someone else’s character for a long time… nope, never happens.

“And GamerGate is, I think, the poster-child event for people not knowing how to behave on the internet; i.e., a total clustercuss of baiting statements and wild unfounded allegations instigated by overblown reactions to false statements, in which just about everyone involved said or did something stupid.”

If your reaction to campus protests is that it is a big problem, and your reaction to GamerGate–in which the side for which Christina Hoff Sommers was a prominent advocate drove people from their homes with death threats, harassed them nonstop, exposed the details of their bank accounts, and incidentally prevented at least one of them from giving a speech on a campus by threatening a massacre at the event–is that there were faults on many sides, I don’t know what conversation there is to have.

“people who aren’t really racist (or fascist, sexist, etc.) receive that label. So while “support for free speech” across categories might be growing, the number of people lumped into a category for whom that right is denied is also growing.”

If you look at the data from which the graph shown in the article is drawn (http://jmrphy.net/blog/2018/02/16/who-is-afraid-of-free-speech/) the question asked of survey respondents in regards to racists was about “…a person who believes that Blacks are genetically inferior.” (The question was “If such a person wanted to make a speech in your community, should he be allowed to speak, or not?”) So what the data shows is support for free speech for people *with that specific view* has remained pretty much constant (and amongst the extremely liberal has actually *grown*). I suspect that “…a person who believes that Blacks are genetically inferior” provides a pretty decent baseline – if someone thinks such a person should be allowed to speak, they probably would extend that right to speak to people with other views classified as “racist.”

You’re right. It has remained more or less constant, with variations primarily within 10% over the past 30~ years; and it has grown among the “extremely liberal”, though declined among both “liberal” and “slightly liberal” (which together, with “moderates”, “slightly conservative” and “conservative” comprise many more than the “extremely liberal” and “extremely conservative” [where it has also grown], as is indicated by the *overall* decline). That’s not the point I was making, though.

The point is that people who in no way believe that “Blacks are genetically inferior” are presumed to believe that “Blacks are genetically inferior” because they believe, for instance, that Thomas Jefferson did some good things despite being a person who owned and abused slaves in a reprehensible fashion, or that having more white than black authors in a college course is acceptable.

More and more people support free speech, so we should not be so concerned about the increasing number of mobs silencing speakers.

A bit like saying:

Fewer and fewer violent crimes are being committed, so we should not be so concerned about the increasing number of school shootings.

“the increasing number of mobs silencing speakers” — I think we disagree on the facts here.

“we should not be so concerned” — There are reasonable questions to be had about where to spend our time, attention, and resources. If the mainstream narrative has overblown the problem, that indeed would be a reason in favor of diverting our time, attention, and resources to other issues in higher education.

Great. You can do that. For those of us who see the problem occurring at our institutions and who are more concerned about it than you can do our own thing.

I think it’s pretty clear that the number of speakers being shouted down has dramatically increased. This has been the observation of all sorts of people of various political persuasions. Now, if you have data that contradicts that perception, I’m open to it. But absent data, I see no reason why the perception isn’t likely to be accurate. Self-reporting does not count as the relevant data.

That said, I think it’s worth considering that some of these mobs may be motivated by “softer” unjustified uses of force, that have happened in the past. An LGBT speaker in 1985 might not be shouted down, but they might be kept from speaking in other ways, using other political ways of manipulating things. That’s worth realizing. Those that sow the wind sometimes reap the whirlwind. (But we needn’t say that those who bring the whirlwind with them are justified in doing so.)

The data and claims above specifically about college students should be looked at alongside the data in the Gallup surveys of college students in the Inside Higher Ed article below.

http://insidehighered.com/news/2018/03/12/students-value-diversity-inclusion-more-free-expression-study-says

This would seem relevant.

https://www.chronicle.com/article/College-Students-Want-Free/242792?cid=at&utm_source=at&utm_medium=en&elqTrackId=ae6d5f9157f644b6a102586b5f0bfc50&elq=26b1a026fca144c3920b4ca09600741c&elqaid=18145&elqat=1&elqCampaignId=8088

I think you’re missing the real concern critics of mob silencers, social justice activists, etc.: It is not that there is necessarily an overall trend, among college students or non-college students, against support for free speech in the abstract as a principle one endorses or not, but that a vocal minority is wielding outsized influence and that this is leading to changes in norms and policies that favor a specific ideological perspective, and that this is achieved in part through the demonization of opposition.

These critics are more concerned with e.g. the denial of due process on college campuses, twitter mobs, major social media companies playing political favorites and selectively censoring viewpoints they don’t like, fear of being seen as racist inhibiting individuals and institutions from addressing sexual assault and other crimes in Europe, etc. Even the college protests need not be indicative that a particular viewpoint is becoming widespread; it need only be indicative of a particular viewpoint having the momentum and support to influence school policy and have a cultural impact. Most of the action is not even taking place on campuses but is taking place online, e.g. twitter and other social media outlets, and various online publications.

I believe you are being uncharitable towards the points of view you disagree with and are seizing on flimsy evidence to justify dismissing them. The burden of proof is certainly on proponents of these claims to make the case for them. You can easily point out that they have not done so in most (or all) of the cases I’ve cited, and that’s enough. You do not need to grab on to feeble evidence to unilaterally declare a given set of concerns “baloney.” That’s premature and isn’t warranted by this particular study.

As others have pointed out, there are any number of studies and reports that point in the opposite direction.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/18/have-millennials-given-up-on-democracy

https://www.forbes.com/sites/neilhowe/2017/10/31/are-millennials-giving-up-on-democracy/#511fae772be1

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/14/opinion/sunday/millennials-freedom-fear.html

As someone who has taught in the university in some capacity since the early 90’s, I have observed a profound shift in attitudes among students towards how we should deal with challenging, upsetting, even offensive ideas. The notion that this is not the case — or that young peoples’ attitudes have become more liberal, rather than less — strikes me as fundamentally unserious, at least if one has been paying attention. Certainly, they have become more *progressive* but that is not the same thing and in its current form is as often as not, antithetical to liberal ideas, in the Lockean and Millian senses.

“fundamentally unserious, at least if one has been paying attention”

Why must you use such pompous and condescending language, Dan? It is very frustrating.

In any event, my position is not “unserious.” Try taking the long view.

If you paid more attention to the long view, you’d see that what’s often happening is not some “shift in attitudes among students towards how we should deal with challenging, upsetting, even offensive ideas” but rather a shift in which ideas these are.

To take just one example: consider the idea that homosexual activity is morally permissible and culturally acceptable. It wasn’t long ago—several decades at the most—that many students would have found this to be “challenging, upsetting, even offensive.” It wasn’t long ago that people, including students, responded to this idea with mockery, scorn, shunning, and violence (of course there’s still some of that), and institutions engaged in discrimination and bans. These were certainly not liberal responses!

There are so many ideas whose expression has gone from suppressed to allowed over the past 100 or so years, including on college campuses. These should factor into any “serious” thinking on this matter by people who are “paying attention.”

Unfortunately, what often ends up happening instead is that people see that culture seems different now compared to the narrow bit of it they were exposed to and liked when they were younger, and are attracted to narratives which explain why it must now be worse. This often involves ignoring the long view (not to mention, again, susceptibility to the availability heuristic and confirmation bias).

I don’t know how to count ideas, but if I did, I’d bet that there are a greater diversity of ideas more freely discussed on college campuses today than ever in history.

This is not to say that we shouldn’t tell students, for example, that they ought not to march into a lecture and shout down the speaker. We agree on that.

But the declinist view you offer does not seem to be supported when more and more evidence is taken into account.

Why must you use such pompous and condescending language, Dan? It is very frustrating.

= = =

Says the guy who posted a picture of a giant shit-statue at the end of an article on my What is it Like to be a Philosopher essay. (Yes, I read your explanations. Not very convincing, I have to say.)

I don’t think what I said is nearly as bad as you make it out to be. In the annals of pomposity and condescension, it strikes me as scoring pretty low.

Hi Justin,

Speaking from my own experience–which, being early career, is still fairly limited–its true many ideas formerly suppressed are now allowed, even encouraged. On the contrary, however, ideas which were formerly taken for granted, common, or mainstream are now being themselves marginalized–even when they are not simply being pushed forward as the “obvious” norm, but defended through rational inquiry. For instance, I found that the majority of my students at my last school were afraid to question post-gender ideology. The idea that gender may be biologically based (not exclusively biological, but biologically based and culturally augmented) was anathema.

Few students were willing publicly to admit they believe in God or practice Christianity; or if they did, they qualified it with statements about how progressive their Christian belief is in regards to homosexuality, race, reproductive decisions, etc.

Few students were willing publicly to admit they support the Second Amendment, or that they don’t think guns are the cause of violence.

Few students were willing publicly that they’re Republican, or Conservative, in any way. There was a real fear of being targeted if one said something conservative. Being on the more conservative side myself, I *very frequently* had students *privately* thank me for presenting a point of view that they never heard anywhere else.

That is, I think there may be more ideas discussed on college campuses today, but I don’t think they’re very diverse from one another, ideologically speaking. My impression–and again, this is very limited, and formed most recently from being at college in Boston (surrounded by other colleges in Boston, of course)–is that the supremacy of one’s own interpretation of one’s own lived experience is inviolable; and this belief undergirds the majority of the popularly-discussed, widely-publicized views on college campuses.

I didn’t look at them all, but the first article you cite doesn’t seem to be particularly on point.

It’s reports that Australians between 18 and 29 are less likely to state that democracy is the best form of government than their older cohorts. It then reports their reasons for saying as much: “Millennials themselves, asked why they do not back democracy, mostly say it “only serves the interests of a few” (40%) and that there is “no real difference between the policies of the major parties” (32%).”

The article then goes on to note that: “The twist is that while they disdain democratic institutions, millennials engage in the cut and thrust of democracy with vigour.”

I’m not sure how you go from that article to the conclusion that young people are extra-sensitive, or somehow opposed to free speech.

I didn’t. I said that there are a number of studies that suggest that point in a direction different than that described by Yglesias.

The post is about support for free speech, and suggests that support for free speech is increasing and that college students are less likely to support restrictions on speech. You say that there are a number of studies and reports that “point in the opposite direction.,” and then cite that article. You immediately follow it by reporting your own view that you have “observed a profound shift in attitudes among students towards how we should deal with challenging, upsetting, even offensive ideas.”

How does the first article you cite “point in the opposite direction” of the view that support of free speech is increasing, and is particularly strong among college students? How does the article support the view that there has been “a profound shift in attitudes among students towards how we should deal with challenging, upsetting, even offensive ideas”? As far as I can tell, the article only suggests that 19-29 year old Australians think that democratic systems aren’t in fact very democratic, and that that same group is very active politically.

A bunch of students say they support free speech. That doesn’t necessarily mean they genuinely do. Desirability bias and all.

Further, the narrative isn’t that campuses have free speech problems because the majority of students are illiberal. The narrative is that they have free speech problems, period, and then that the best explanation for that this a vocal and organized illiberal minority makes trouble.

If the mainstream media switched from stories about “students these days” and “college campuses are bastions of intolerance” to “a vocal and organized illiberal minority makes trouble,” that would be an improvement.

Your impressions of the titles presented in mainstream media seems somewhat different from mine.

Or we’re not applying the term ”mainstream media” to the same news organizations.

This data shows that there is far more tolerance for communists, militarists, homosexuals, and atheists. Speech that used to be censored by the right is becoming more tolerated. That is a good thing, but it is hardly surprising in a campus culture that is increasingly collectivist at the expense of traditional liberal values of individual rights.

There is less tolerance for racist speech, which on the surface is a good thing. However, there is a cultural narrative right now that is hair-trigger quick to brand someone a racist, fascist, sexist, trans-phobe, or general bigot, even for people who don’t deserve to be lumped into and treated in the same category as Richard Spencer. Look at what happened to Rebecca Tuvel for instance. I would like to see data that shows trends for tolerance of speech that is considered “sexist, homophobic”, etc.. I think those would all point sharply downward with steep gains in recent years. That is again a good thing on the surface, unless you can too easily be painted as falling into one of those categories for saying the “wrong thing”.

Importantly, the punishment for saying the “wrong thing” is new – online shaming and humiliation – and this is a potent force that is arguably similar to the type of fear the state was able to instill against communism during McCarthyism. The threat of online shaming has created a much deeper fear of saying the wrong thing, since the repercussions are so much more profound then what we’ve been used to for decades at least. I don’t think that the author’s data captures that phenomenon effectively or that the questions are specific enough to get at that phenomenon.

I know that just from my personal experience that I’m much more afraid as a professor to speak on controversial issues in class out of fear that I may be reported to the Internet for accidentally saying the “wrong thing”. Unlike economics, the high profile incidents that the author dismisses have a trickle-down effect. We look at what happens to these people, sometimes major repercussions for the slightest offenses even if the dissent is reasonable (see Evergreen State), and say “better keep my mouth shut”. If you don’t believe me, go openly challenge Internet collectivist orthodoxy at a “progressive” school in California and see what happens. Have fun with that. You will be attacked FOR being a liberal and tarred and feathered online.

While you are right to suggest that we should look at the data to support our conclusions, I think you should think over your conclusion that this author’s data really shows that these concerns being expressed are “baloney”.

I don’t think anyone knows how widespread it is, but there can be no doubt that a vocal contingent of well-connected young people in and around college campuses today are using violence to keep people from expressing and discussing verboten ideas. Think about Berkeley’s response to Milo, or recent outbursts against Christina Hoff Summers, or the Evergreen fiasco, or the students who assaulted the speakers at a discussion with Charles Murray at Middlebury College, or the philosophy instructor who is alleged to have assaulted a protester with a bike lock. These aren’t one-off random events, but rather the result of collective (and ill-focused) effort on the part of people who share political and ideological convictions about violence and free speech.

This is only to focus on the violent manifestations of this tendency, and only on the left. Equally violent tendencies are manifest on the right, though I don’t know of a comparison between the alt-right and ctrl-left when it comes to the suppression of others’ speech. Things looked very different in the U.S. in the 1950s, for instance, and this suggests that the problem is social rather than psychological. And given the drastically left-ward ideological shift the humanities and social sciences have made in the last two decades, it’s not surprising that the non-violent suppression of speech we hear about is mostly coming from one direction.

At any rate, it is not surprising that people are calling attention to the ctrl-left’s violence. So I fail to see how surveys show that the problem is ‘baloney’. A global increase in generally favorable attitudes toward freedom of speech is compatible with concurrent local growths in the violent suppression of speech at places like Berkeley, Evergreen, and Middlebury. And if that’s happening, it’s worth drawing to salience as a characteristic feature of at least some college campuses today. The existence of this kind of behavior at Berkeley, of all places, is a problem the intelligentsia on the left would do well to face more directly.

The whole issue is a *small*, noisy minority of authoritarian left wing crazies who want to control speech! I agree with those above: this overall trend, accepting there is one (i.e. putting aside issues with the methodology), obviously does not contradict this *at all*!

There seem to be a lot of people who insist there is a real problem, and a lot of other people always insisting the problem is fake. Would anyone be willing to preregister some hypotheses about the kind of data that best decide the question? Assertions tell us something, but perhaps there are other more informative measures, concerning behavior, structures, or policies.

I second the call for preregistering some predictions. Perhaps a prediction market could either supplement or function better, as well. If someone puts together a place for us to make specific predictions I’d be willing to do so.

To those saying it is “obvious” that students are less willing to engage with upsetting or controversial ideas based on their own anecdotal experience, let me offer my own anecdotal experience as a counterweight.

I am a fairly recent graduate of a major state school that has a reputation, at least locally, of being extremely liberal. And yet, my experience at the university completely contradicts the narratives of those who claim there is a free speech crisis on campus. Conservatives were and are regularly invited to speak and sit on panel discussions, and not one of them was shouted down, censored, or threatened. I only remember one incident of a speaker being protested at all–Milo, not exactly representative of normal conservatives–and that protest was peaceful, small, and remained outside the venue (and contained less than two dozen people on a campus of tens of thousands). Furthermore, I never once encountered a trigger warning in class, nor demands for safe spaces. Indeed, I regularly witnessed discussions in classrooms and at talks about controversial issues such as sexual consent, abortion, religion, Trump’s election, and immigration (to name a few) where the audience may have been at times uncomfortable or critical, but always respectful and willing to engage in dialogue. Most of my Professors seemed to be left-of-center (though by no means radicals either) but they always were open to a variety of perspectives and never shamed or discouraged those who had more conservative views. In short, I have never experienced the angry social justice anti-speech movement that many claim exists.

This isn’t to say there aren’t isolated incidents of no-platforming, heckling, and the like. But I’m not convinced these are more common now than in the past, it’s just that now things can go viral online whereas in the past these stories would have remained only local.

These are good points, but they are consistent with the idea that it’s becoming more common that people will get drawn and quartered for putting forward certain controversial theses. Something can be rare and yet be increasing. There may be something of a reaction that you’re describing, though, which is interesting: perhaps the vitriol is making academic progressives more self-aware and accommodating in person, if they don’t decide to be “SJWs”.

But I think online is another story. Online, one’s passive-aggressive frustrations can be voiced openly. I mean, consider the APA conferences as a microcosm — you hardly hear ANYthing vaguely conservative there, but the internet is full of philosophy ne’er-do-wells like me experimenting with conservative ideas, at least to some degree. And the internet witch-hunts can be intense and brutal.

That we have cute language that tries to normalize this kind of behavior–“no-platforming,” for example–suggests to me that the problem isn’t just imaginary. The Overton Window has shifted on this issue. The discussion now isn’t *if* this kind of behavior is appropriate but *when* it is (or isn’t) appropriate.

Related: “Is There A Defense of Shouting Down A Speaker At A University?”

I’m not saying or suggesting that anything here confirms or disconfirms the content of this post. But, here’s an interesting, related discussion:

https://the1a.org/shows/2018-03-15/censoring-speech-on-campus

There also was this article in the WaPo a few years ago.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/rampage/wp/2015/12/01/measuring-millennials-support-for-censorship/?utm_term=.e08495de5be8

3 years ago, I stood up for the civil and constitutional rights, including free speech and religious expression rights, of our only POC job candidate, and some of my graduate student peers tried to have me removed from our program and socially ousted me from the department, turning me into a pariah. So, there’s that.

An article published on Monday:

https://www.chronicle.com/article/College-Students-Want-Free/242792?cid=at&utm_source=at&utm_medium=en&elqTrackId=ae6d5f9157f644b6a102586b5f0bfc50&elq=26b1a026fca144c3920b4ca09600741c&elqaid=18145&elqat=1&elqCampaignId=8088

“Fifty-six percent of college students say protecting free-speech rights is extremely important to society, according to the poll of 3,014 college students that was conducted in the fall of 2017. They also say they overwhelmingly favor an open learning environment that allows all types of speech on campus over one that imposes limits on words that might be considered offensive.

“But respondents’ commitment to open debate was inconsistent: Nearly half of students say they favor campus speech codes; nearly two-thirds do not believe the U.S. Constitution should protect hate speech; 73 percent support campus policies that restrict hate speech like racial slurs; and 60 percent say the same about those that discourage stereotypical costumes.

…

“Their opinions on free speech are changing rapidly. Support for campuses that allow all types of free speech, over those that limit offensive speech, dropped from 78 percent to 70 percent since the survey was conducted in 2016.”

All of those free-speech studies contain semantic exceptions, which make them meaningless as applied.

A modern-day student may well claim to support free speech “except in cases of violent speech.” But the problem is that they see “violence” very differently than their predecessors: while I think of immediate incitement to direct physical harm (which is incredibly rare) they use the word to refer to more general speech, so they apply it broadly.

If you allow them to indiscriminately classify opponents as “hate speech” then of COURSE they will come off looking like they support free speech. But that is a question problem.

Everyone say it with me — “Hate speech is constitutionally protected free speech.” Again — “Hate speech is constitutionally protected free speech.”

If you don’t support hate speech (the right to speak it, not necessarily the content), then you don’t support free speech. I like to say that I love hate speech and pornography, and I hate hate crime legislation.

Heterodox Academy has a pretty good takedown of the Yglesias essay and the twitter thread that preceded it. They also operationalize three hypotheses concerning what one would expect to find if the hypotheses were true:

https://heterodoxacademy.org/skeptics-are-wrong-about-campus-speech/

“Over the past two weeks, Jeffrey Sachs (a political scientist at Acadia U; not the economist at Columbia) has made the argument that There Is No Campus Free Speech Crisis, as he put it in a long twitter thread on March 9. Matt Yglesias then expanded on Sachs’ argument in a post titled Everything we think about the political correctness debate is wrong, and Sachs expanded his case in a Washington Post Monkey Cage essay with a similar title: The ‘campus free speech crisis’ is a myth. Here are the facts. Sachs and Yglesias both draw heavily on analyses of the speech questions in the General Social Survey, which were plotted and analyzed well by Justin Murphy on Feb. 16. In this blog post we will show a reliance on older datasets and the failure to formulate the question properly have led Sachs and Yglesias to a premature conclusion. Something is changing on campus, but only in the last few years.”

I guess that “bologna” is actually a filet.

I was coming here to post this as well. I am curious what Weinberg’s thoughts are on this piece. As I stated in one of the first posts in this thread, “It is not that there is necessarily an overall trend, among college students or non-college students, against support for free speech […] but that a vocal minority is wielding outsized influence…”

Many of the more credible concerns about free speech are entirely consistent with increased overall support for free speech among millennials; this is just the wrong operationalization of what the claim even is, so data on it can’t “refute” what critics are claiming.

Here’s a follow-up piece from Heterodox academy that puts another, and I think final, nail in the coffin of the Yglesias and Sachs pieces.

https://heterodoxacademy.org/the-skeptics-are-wrong-part-2/

Seems pretty decisive to me. If anyone has a way to salvage the ‘baloney’/’myth’ dismissal of concerns over the trend these past three years, I’d be interested to hear it. Otherwise, it’s time to get our heads out of the sand and do what we can to salvage what’s left of our universities.

Dear 2018,

Matt Yglesias was just a co-signatory to a quite widely discussed letter claiming a growing problem with free-speech culture, so he may have changed his mind.

Yours sincerely,

2020

PS don’t make any travel plans for the year after next.