What Does The Public Call What We Call “Public Philosophy”?

We are accumulating a large list of philosophers who do public philosophy in the comments to “Who Does Public Philosophy?” It is great to see that so many academics are involved in bringing philosophy to people outside their classrooms and peer groups, and especially heartening to see so many names on that list of people who haven’t been much mentioned before in the philosophy blogosphere. Perhaps even more people will be encouraged by this showing to engage in public philosophy themselves (see work on descriptive norms).

I wanted to draw attention to one comment to that post that raises an interesting topic. It’s from Nathan Nobis (Morehouse):

I’ve been wondering this about public philosophy. On the “supply” side, it’s called Public Philosophy. Has anyone though tried to figure out what the “demand” side might call it? I.e., for people who are seeking public philosophy, how do they seek it? I doubt they go out looking for something called “Public Philosophy”! So how do they seek what we hope they will find, or do we just put stuff out there and hope it is found, even though people aren’t really looking for it?

Patrick Lin (CalPoly) replied:

They most certainly do not call it “public philosophy” outside the discipline. In ethics at least, ethics is sometimes subsumed under “law and policy” or “societal impact”; but it’s hardly ever called “philosophy” unless it’s an academic meeting. “Philosophy” is not a selling point but a negative indicator for many, i.e., “ethicist” is more credible than “philosopher.”

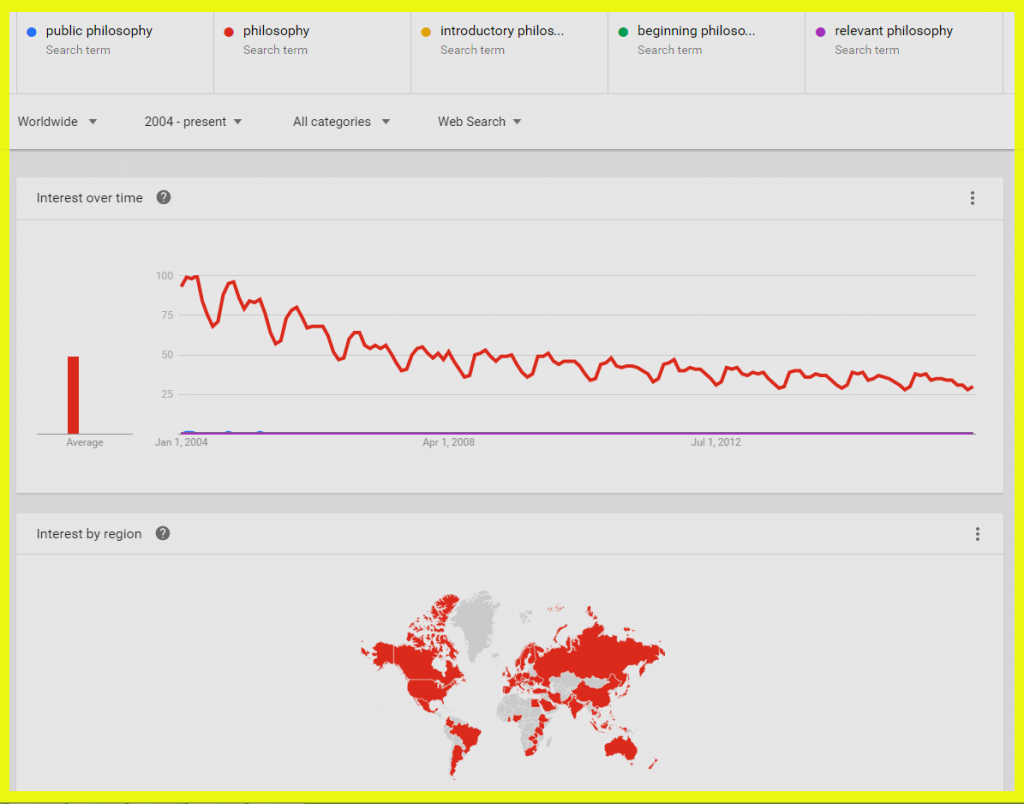

Professor Nobis provided a link to a Google Trends search he did using the terms “public philosophy,” “philosophy,” “introductory philosophy,” and others. As you can see, “public philosophy” barely registered, in comparison with “philosophy.”

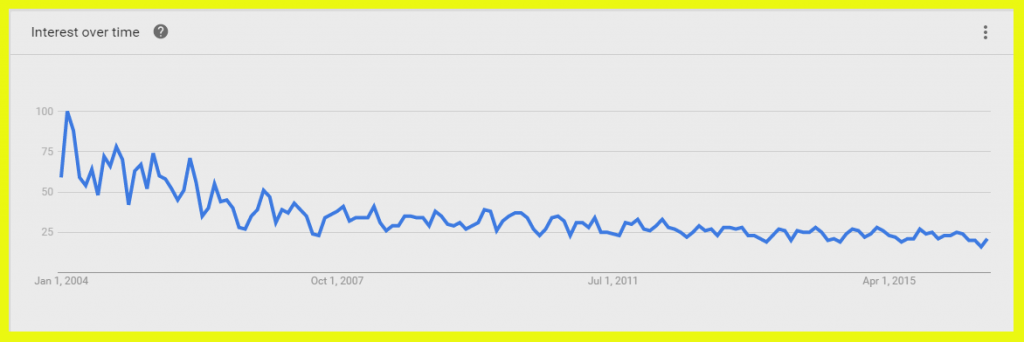

Here are the graph for “public philosophy” on its own:

These are trend lines, with “100” representing peak popularity of the search term relative to other times. So there appears to have been a decrease in searches for “public philosophy” over the past 12 years.

We might be led to ask: when the public is searching for what we are calling “public philosophy,” what do they call it? Knowing that, or what terms resonate with people in their search for public philosophy, might aid in the success of public philosophy initiatives. Comments on these matters welcome.

Simply put, I think “philosophy” has connotations of “head on the clouds while walking into a ditch.” When they hear that buzzword, they imagine we’re essentially Ivory Tower bullshit artists (thanks, Monty Python).

They do seem to like the term “consultant” though. Sounds much more business like as well as carries connotations of expertise.

One reason the previous thread has so many entries is that one expectation of tenured and TT faculty at many institutions is a service component. While part of that is met with institutional service, many public institutions (like mine) encourage community service that is discipline-related. So, in my own case, I’ve served on my state’s Office of Lawyer Regulation committee for about 20 years now, and tried to bring my skills as a philosopher to bear on the cases we deal with (useful distinctions, clarifications about language, epistemic interpretations relating to standards of evidence, etc.). I’ve also written letters across my career to my state’s major newspaper, and almost always about issues with a strong philosophical component. (One earlier this year defending abortion access earned me an anonymous death threat left on my answering machine!)

I don’t think I’m at all exceptional in this way. So maybe we should call “public philosophy” “discipline-related public service” or something like that.

Agree with Henri, including the use of “consultant.” Learning the code is crucial for branching out beyond the discipline. As I also said on the original thread: “responsibility” and “values” are also codespeak for ethics, outside of philosophy.

To call yourself a philosopher — as opposed to a consultant, ethicist, college professor, etc. — is to misunderstand what others /think/ they want or need. You gotta sneak philosophy in there, like medicine with food.

Otherwise, if you don’t even know your audience and other key stakeholders, how can you be trusted to know what you’re talking about, on issues that perhaps concern mostly them? For instance, if you’re talking about AI design to technology companies, you better know their lingo and something about their industry, or you’d lose most or all credibility from the start. Folks don’t take kindly to outside agitators since at least 399 BC.

(It should go without saying that stealth mode also means dressing the part, but I’ve seen this mistake committed in many meetings. Those philosophers tend to not be invited back, which maybe isn’t the goal, but this means their impact is diminished.)

here in Iowa the general consensus seems to be something like pointy-headed ivory tower liberal elite spin doctors tho not in those terms.

In line with the other comments, the average person thinks of philosophy as disconnected from their everyday life. The professional philosopher is nothing more than a master of “semantic games.”

I think the public would be more open to public philosophy if it was titled something like “practical” or “everyday” philosophy.

In an attempt to remedy misconceptions, I’ve actually engaged the public. Most seem at least somewhat willing to embrace philosophy, but don’t know where to start. I think having more professional philosophers go out into the public (literally) is a good move. It’s easy for the average person to dismiss philosophy when it’s too esoteric, technical, or removed from everyday life, but when you explain to them what philosophy actually is, and its relevance, (face-to-face in a polite and easy to understand manner) the appeal of philosophy becomes obvious to even the most skeptical of philosophy. I understand this might not be the most efficient way, but I think it’s a good way to reach out.

Shameless plug: https://sites.google.com/site/streetphilosoph/

I don’t think that we should call public philosophy “practical” or “everyday” philosophy, since the fundamental issues it deals with could include any of the fundamental issues philosophers deal with. Is the question of whether the external world is an illusion a “practical” or “everyday” question? Arguably so, but calling it that could easily be misleading. Also, some issues are clearly “practical” but not “everyday”. At what point, if any, we should give rights to artificial intelligences is a practical issue, but not one most of us face every day.

I don’t think public philosophy should include everything that professional philosophers do. I think that’s what turns off most people to philosophy.

Basic ethical and epistemological questions that are obviously intertwined with “everyday” experience are the best way, in my opinion, to reach people and spark interest. “Can opinions be wrong?” “Are you living a good life?” “Do you really have any rights?” etc. are the types of question I think are best used as an introduction. Later on, if further interest is presented, a laymen can delve into the deeper philosophical questions.

I think the tag of “everyday” philosophy is a good starting point. It does exclude a large amount of philosophy, but that maybe necessary to get people interested in the first place. Also, I agree that, you’re right, “practical” is probably a bad fit here. “Everyday,” though, (meaning everyday for the average joe) doesn’t seem problematic to me.

“In line with the other comments, the average person thinks of philosophy as disconnected from their everyday life. The professional philosopher is nothing more than a master of “semantic games.””

To be fair, many philosophers have criticized the current state of analytic philosophy for if not “semantic games” then for an undue focus on language.

“We might be led to ask: when the public is searching for what we are calling “public philosophy,” what do they call it?” If they are searching for public philosophy in the first place, they probably call it “philosophy”. It is, after all, philosophy they are ultimately looking for. They might possibly call it “popular philosophy”, since accessible science books are often called “popular science”. They are unlikely to call it “introductory philosophy” or “beginning philosophy”, as in the word search above, because that suggests that it is a stepping stone to real philosophy and not real philosophy in its own right. They also aren’t going to call it “relevant philosophy”, as that suggests that there is such a thing as self-labelled “irrelevant philosophy”.

Mostly, though, people don’t know what philosophy is. If they knew what it was, and knew that it is available in accessible forms, I think they would access it a lot more often than they do.

If we took a non-elitist view of philosophy and a non-condescending and more Deweyan view of the public, we’d get this kind of answer: public philosophy is a collective (philosophers with the help of publics) inquiry into what is at the root of our troubles and what might be done to ameliorate them. I worry that notions of public philosophy as aiming to educate the masses completely misses this point. Public philosophy ought to change what WE do not just what the public knows. Our own work should change — should become more engaged with the world — if we’re doing our work from a public point of view. Then some supposed problems become pointless to pursue and others that we might have otherwise ignored loom large. This still leaves plenty room for other philosophers to work on things that might seem pointless today. Tomorrow they could serve a huge point. Think Whitehead’s process philosophy or Spinoza’s passions…

Noelle, I think that the definition of “public philosophy” should be kept as politically unloaded as possible. A “public toilet” is a toilet for use by the public. A “public park” is a park for use by the public. A “public orchestra performance” is an orchestra performance to be accessed and enjoyed by the public. This is so, whether they are toilets, parks and performances that serve the public well, or do their job badly. Likewise, “public philosophy” should mean philosophy to be accessed and used by the public. If we label only a subset of philosophy accessed and used by the public as “public philosophy”., that will cause much confusion I think.

Hey Nonny Mouse, yes, of course. But note I began this with a big “if” and I do hope that IF is instructive for how we might think of our work. But more than that I think that thinking of the public as an audience to be served is just super condescending.

I think hoi polloi talk about “popular philosophy” but to academics,

“public philosophy” has other connotations. Popular philosophy is stuff people write to disseminate other people’s ideas to a wider public. Public philosophy, on the other hand, is original work that’s written in such a way that it’s accessible to a wide audience. Practitioners of public philosophy are people like Singer, Nussbaum, Dennett, etc., to name some of the stars. Practitioners of popular philosophy would include folks like Daniel Klein and Tom Cathcart, authors of books like Plato and a Platypus Walked into a Bar. People doing public philosophy have rather different reasons for doing it, I would say. They are people who are “doing philosophy” but find value in doing it in such a way that they have a lot of contact with general concerns. Also, they tend to be people with an interesting in both philosophy and good writing.

How does the public find public philosophy or popular philosophy? Well, bookstores don’t sell much besides public philosophy or popular philosophy. You can tell which is which based on affiliations. Generally speaking, public philosophers are academics. Not invariably, but usually! Popular philosophy is much more fun and marketable. But these categories are obviously imprecise.

As a member of the public I can report that I would call public philosophy ‘philosophy’ and know nobody who would do differently. The ‘public’ qualifier may be useful in some contexts but from the end-user perspective I wouldn’t know how to distinguish the ‘public’ kind from the ‘private’ kind. I suppose ‘public’ indicates accessibility, in theory, but in practice it may or may not.

I think that inferring a trend from the graphs would be a mistake. The Google ngram viewer reveals that “public philosophy” got negligible usage before the early 1950s. Although it has declined since 2000, it is still above the low point from the 1970s.

https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=public+philosophy&year_start=1940&year_end=2008&corpus=15&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2Cpublic%20philosophy%3B%2Cc0

I think the public would call it “jack ass-ery” if Spiros’ (Philosophers Anonymous — RIP) efforts were were characteristic. Ah, Spiros we — or at least I — miss you so.

A common exchange with many family and friends when I was in academia.

Uncle: “How is the psychology program going?”

Me: “It’s not psychology, it’s philosophy.”

Uncle: “Oh, like the meaning of life? So, what do you think is the meaning of life?”

Me: “Actually, my dissertation is on the philosophy of mind, on the nature of consciousness, and foundations of cognitive science?”

Uncle: “Oh, ok.” [With a blank expression].

Takeaway from this: Much of the public lives in a world divided between religion and science – as they see it, religion provides (or aims to, or fails to provide) a sense of meaning and purpose, and science tells us how things work. Philosophy as separate from religion and science (but overlapping with both) is a hard thing for most people to hold onto (including many priests and scientists). And insofar as the general public has a grip on this middle ground of philosophy, they are more apt to think of it in terms of new age thinking (Deepak Chopra, Echkart Tolle, etc.), which self-consciously aims for taking on the role of religion in a secular society (hence “new age” – global, cosmopolitan, etc.).

So academic philosophers have three competitors (as it were), who more easily have a grip on the general public: priests, scientists, and new age thinkers. To get the public more interested in philosophy as done in academia, academics need to contrast and compare, or collaborate, with these three groups. Ignoring these three groups, or being dismissive of their simple mindedness, is counter productive. This is one way people like Dennett have done a good job of getting academic philosophy in the public sphere – because he contrasts himself with and critiques religion. I think he is wrong about this, but at least it is clearing the ground. Public disputes – stirring the pot – are a great way to get the public interested.

So: if there is a worry that what are here denoted as “public philosophy” and “popular philosophy” are in some way carried out by people (some of whom claim to be philosophers) who have different interests and affiliations and motivations and beliefs and world views; and: if there is a general concern that this apparently fragmented situation doesn’t really help the “public” either grasp the overall terrain of philosophy very well, or help the “public” to become increasingly motivated to improve the ways in which public or popular philosophy are understood; then: would it be helpful to develop some tentative and overarching collective agreement about what the WORK of philosophy might be? Could such a formative invitational explanation help “the public” (not to mention some philosophers) enhance their understanding of the topic at hand, and to join in that work to help clarify, at least somewhat, what that work is all about, in whatever ways make sense and have positive value?

B. Leezard

“…if there is a general concern that this apparently fragmented situation doesn’t really help the “public” either grasp the overall terrain of philosophy very well, or help the “public” to become increasingly motivated to improve the ways in which public or popular philosophy are understood; then: would it be helpful to develop some tentative and overarching collective agreement about what the WORK of philosophy might be? ”

Surely it’s the results of philosophy that are important, and without those why would anyone be interested in the work? Give the public some results and they’ll be a lot happier.

“—Could such a formative invitational explanation help “the public” (not to mention some philosophers) enhance their understanding of the topic at hand, and to join in that work to help clarify, at least somewhat, what that work is all about, in whatever ways make sense and have positive value? ”

It does not seem to me that many philosophers are in a position to help the public understand philosophy. Charity begins at home.

Well, PeterJ: I see you’ve said something about philosophy needing to have and show “results” in at least one other discussion thread on NOUS. I, along with many others, agree quite strongly that philosophy ought to do that, and not only in “public” and “popular” philosophy, but in all realms. However, it seems to me that exhorting “Dammit, Jim, show results!” doesn’t get at the point I raised earlier, namely: it is important to discuss and identify what the “work of philosophy” is about. In this space-limited forum, I won’t build a full supporting framework but will, rather, develop my points as quickly as possible (however coarse this may be). So, if the work of science is to advance knowledge by rigorously developing testable and falsifiable hypotheses based on varieties of reliable evidence about things we decide are sufficiently interesting and important to serve as foci for our admittedly limited energies and attention, and also to explore and develop reliable methods for both determining what counts as evidence and applying those methods to develop and test our hypotheses (to claim reliable knowledge about some thing, or to frame up plausible laws, for example), then, in parallel, the work of philosophy is to advance knowledge in accord with equally stringent standards of rigour, but in realms where the objects of our attentions and the terms of reference for knowing as much as possible beforehand are not and cannot be known in advance. This means that the work of philosophy rigorously raises leading-edge questions and develops approaches to developing and exploring those questions having to do with how to think well about what it is we are discovering, the methods we employ to engage in discovery, and how it is we can develop and adhere to the highest standards of reasoning, investigating and acting. The work of philosophy thus allows us to deal as effectively as possible with challenges that arise in all other realms of developing our knowledge, as well as managing our affairs. The work of philosophy helps us think about our thinking and helps develop the most rigorous methods of drilling further into what we already think we know (thus, the leading edge of science), as well as pushing our explorations and inquiry as rigorously as possible into areas about which we may make terrible mistakes about being certain we already know everything we need to know, but in fact know next to nothing (thus, the leading edge of philosophy). Now, if the “public” demands “results” from philosophy to somehow “legitimize” philosophy when contrasted with the presumably “pre-legitimated” work of science (for example) , then it would seem crucially reasonable for anyone making such legitimization demands to ALSO demand to know what the work of philosophy is BEFORE any claims can be made about made about results of that work. So, if anyone was to voice claims such as, “Well, philosophy is useless because it’s a waste of time”, or “philosophy was important eons ago but not anymore because now we know (a lot more about) what we are doing”, or “philosophy is dead because it doesn’t give us any results”, then it would seem reasonable to point out in response that such claims are not statements of fact but are themselves philosophical arguments, and as such require the same level of rigorous analysis and response as any scientific claim. OK — I’ve gone on far too long here, but let us think about the present-day struggles that string theory physicists have rightly recognized as they develop greatly advanced and elegant mathematics while at the same time agreeing that the complexities and levels of development of string theory cannot presently be tested. What should do we do when confronted with such challenges? If the theory, no matter how elegant, cannot today be tested / falsified through what we accept as scientific means, do we de-fund string theory R&D and dump it in the trash bin so that money can be applied to something else? How do we determine current value and likelihood of future value in this case? What do humans do at the leading edge of inquiry when confronted with the real limits of their current investigative technologies and knowledge, but when the work that has been done to this point also suggests much, much more can be done and far more discovered — with profound potential implications? Do we give up, or do we work as hard as possible to innovate further? If we do the latter, I suspect we stand on the work of philosophy to do so.

B. Leezard

Please don’t think I’m dissing philosophy. I reckon I could defend it a lot more vigorously than you just have. I see it as more important than physics. But that is philosophy as a whole and we’re talking specifically about mainstream university philosophy.

—“Now, if the “public” demands “results” from philosophy to somehow “legitimize” philosophy when contrasted with the presumably “pre-legitimated” work of science (for example) , then it would seem crucially reasonable for anyone making such legitimization demands to ALSO demand to know what the work of philosophy is BEFORE any claims can be made about made about results of that work. ”

Fair enough. Let’s assume this condition has been met.

—“So, if anyone was to voice claims such as, “Well, philosophy is useless because it’s a waste of time”, or “philosophy was important eons ago but not anymore because now we know (a lot more about) what we are doing”, or “philosophy is dead because it doesn’t give us any results”, then it would seem reasonable to point out in response that such claims are not statements of fact but are themselves philosophical arguments, and as such require the same level of rigorous analysis and response as any scientific claim.”

The claim that philosophy is dead is clearly false. The claim that university philosophy does not produce results is a common one and seems to be an empirical scientific fact.

We may well disagree on what would count as a result. I’m using ‘result’ to mean a solution to a philosophical problem. If we cannot solve theses problems then what are we going to teach to the public and why should they listen? The only reason would be so that they can do better. But what they are taught is that they cannot do better and nobody can. How is this supposed to generate enthusiasm? They can learn the method but if the method does not produce results what’s the point? This would be what many members of the public that I’ve come across would argue. It’s what I used to argue before (late in life) I started to study.

To be fair, I believe that this form of philosophy can and does produce results and is highly effective. much more so than it is generally believed to be. It would be just that its results are misinterpreted and so appear to be barriers to knowledge rather than a way forward. The effect is the same though, prevarication and inconclusiveness, and an inability to defend itself from criticism. For this reason I believe that public philosophy is an issue that cannot be addressed prior to sorting out university philosophy. A couple of decent general introductions and Joe Bloggs will be pretty much up to speed with the state of the field. It should not be this way.

PeterJ : I agree that philosophy is “more important than physics” and would replace the word “physics” with any other word that denotes any other field of inquiry. As a late-start greybeard myself, I appreciate your collaborative discussion and would have great difficulty interpreting your statements as a dismissal of philosophy. I concluded at the beginning of our exchange that you would not have engaged at all unless you firmly thought the opposite. So, thanks for your perseverance! 🙂 I have time at the moment for a few thoughts. You say, “[t]he claim that university philosophy does not produce results is a common one and seems to be an empirical scientific fact.” First, I will not here ask for clarification of what you are taking to be “an empirical scientific fact” — that can be left for another discussion. Second, what you have said feels like a return to your refrain that “[if] [university] philosophy produced results and showed them to the public [then] the public would think of and act towards [university] philosophy more supportively than how it does now”. Here I think we agree that having a common understanding of what constitutes a “result” is essential, where “result” = “solution to philosophical problem”; and, I have suggested through implication in this thread that “the work of philosophy” must necessarily include “identifying a result as a solution to a philosophical problem”. But, I suspect that herein lies the challenge we are attempting to illuminate in our discussion, namely: [if] you, or I, or anyone else stood up to rationally claim that we perceive a philosophical problem (and we iteratively define it for others so they understand what we mean and that the claim is valid) and, in the same breath, that we understand the essential requirements for effective reasoning (so those ‘others’ understand what that means and that the claim to required methodological adequacy is valid), and, based on the ‘if’, we propose a solution to the identified philosophical problem (and can clearly show to others why the solution as it has been developed works for the perceived problem), that is not the end of it. Why? Because the final step is missing. How do we know this? Because this is where the “so what” question appears, and that lovely question can, as you know — and in bold-faced, sharp-edged practical terms — nullify and even create negative effects from the achievement of the result (e.g., the dreaded “Who cares???”). Said quickly another way: if no links have been clearly explicated BEFOREHAND between the identification of the philosophical problem (e.g., the reasons why the identified problem has plausible relevance to a wider body of stakeholders), the necessary adequacy of the required philosophical work to reach a solution leading to the achievement of the solution as the “result”, BUT at the same time no adequate rational framework of explanation of WHY achieving the result is important / significant / has value has been developed and communicated as a strong backdrop to the work of philosophy, [then] those stakeholders who have a legitimate claim to seeking and understanding good reasons for conducting philosophical work will likely dismiss it, repeatedly finding it irrelevant to their interests and perhaps their world views. This line of reasoning suggests that university philosophy (and may I say that much of philosophy writ large) might usefully map out for the benefit of all doubting stakeholders how and why the development of a complete a “map” (as complete as possible) of the essential philosophical work of optimal reasoning ought to always include the final step of application (and, logically as follows from this line, reformulation). The mythical statement of such a map would essentially be: “This shows you the lay of the land … here’s the identified problem, here are some possible routes to solution, here are some of the obstacles we will likely encounter and this shows some of the steps we will need to take along the way, and this key shows the resources and tools we will have on hand and can use at any time, and so, if we use this map as a general overview approach, we can likely get to our destination, our solution to the problem, the range for which is shown right over here … we may not follow any particular route on this map exactly, and it could be that, because of things we don’t yet fully understand and that we’ll discover on the way, we won’t get to exactly where we think we will as we stand here at the beginning … but, this map shows you the overall orientation and approach and resources we can use to get to where we need to go. As with any other task like this, we just need to be ready for adversity and discovery of things we haven’t even considered yet, and be prepared to adapt all the way as we move forward. What do you say? Sound reasonable? So, let’s do it!” Point being here that if we consistently think ahead and have an overarching approach to avoid the “so what” circumstance, perhaps (as I mentioned in last night’s post) the plausible link between innovation and the work of philosophy could be more clearly illuminated, and could thus be seen to be very attractive by those who might otherwise think that the work of philosophy is worthy only of dismissal “because it never gets us anywhere”. Perhaps what I’ve said here might help the broader population of stakeholders understand that fully embracing the work of philosophy is a noble and potentially very fruitful enterprise. What do you think?

B.L.

I would agree with most of that, (although it was tough going with no paragraphs). But a lot of the work you are proposing is educational – aimed by philosophers at the public (the implication of philosophical ideas and issues, their importance etc.). Most of it would not be necessary for a graduate student ( I hope), and most of it is in vain if in the end we are left free to follow our own opinions. Nothing will have changed.

The topic is too difficult to properly address here, but it ought to be addressed somewhere. There seems to be a lack of ambition, or a belief that although philosophy is a worthwhile enterprise one cannot expect to reach any conclusions. This belief seems to go largely unexamined,

This may be because the search for a global theory is seen as optional. Meanwhile much work is done on sub-problems that cannot be solved without a global theory. My feeling is that the work has all been done but that the outcome has not been interpreted correctly. Philosophical analysis does produce solid results, but only if we recognise that they’re results.

Public philosophy at this time is the dissemination of the idea that philosophy is inconclusive. I don’t feel the public is done any favors by being told this. They ought to be told that this is a view that is not shared by all philosophers and that one entire tradition would want to disagree with it. This is what students are not told.

To go further would be to go off-topic, but as one late-start grey-beard to another I’d be happy to continue by email if you want to pursue this.