Moral Dumbfounding and Philosophical Humility (guest post)

“I need to have the humility to recognize that, in this case, I have not found that truth, and that I may not ever find it. And it has also shown me that I need to be more generous to people who are dumbfounded by cases where I happen to have clear and consistent intuitions.”

The following is a guest post* by Louise Antony, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. It is the fourth in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

Moral Dumbfounding and Philosophical Humility

by Louise Antony

A few weeks ago, at an excellent conference on the epistemology of religion at Rutgers University, I had a terrific conversation with John Pittard. I had mentioned to him, in an offhand way, that my overall reaction to best-of-all-possible-world theodicies was this: if the creation of our universe really necessitated the amount of suffering experienced by sentient creatures on this earth, then God would have had a moral obligation not to create it at all. John then posed the following case to me:

Suppose that you knew of a planet, very much like Earth, that was in the very earliest stages of the evolution of life, with maybe just some microbes, but with no lifeforms even close to sentient. Suppose, further, that it was possible for you to figure out—from its extreme similarity to Earth at the same age—that in all probability, sentient life would evolve, much as it did on Earth. Finally, suppose that you were in a position to destroy the planet before any further evolution occurred. Would you be morally permitted to do it? Would you do it?

It struck me that, given the principle implicit in my view of theodicies, it was pretty obvious I ought to say that I was not only permitted, but even obliged to destroy the planet. After all, I had committed myself to the view that the amount and intensity of suffering that has transpired on Earth is sufficient to have made the creation of the world morally wrong; oughtn’t I to prevent such suffering if I were able to?

And yet, surprisingly, I found myself quite reluctant to say that I would destroy it. Hmm. What was going on?

I bothered John for most of the rest of the conference musing aloud about this. (I’m sure he regretted ever bringing it up.) What I came up with was absolutely nothing that philosophically justified my hesitation. What the exercise taught me was a lesson in intellectual humility—and just possibly—a new sympathy for the kind of dumbfounding I suspect many of our students experience when faced with a thought-experiment that they cannot rationally critique, but that seems to carry them in a deeply wrong direction.

So, with your indulgence, let me set out some of the factors that popped up when I looked within, along with the reactions of interlocutors, inner and outer.

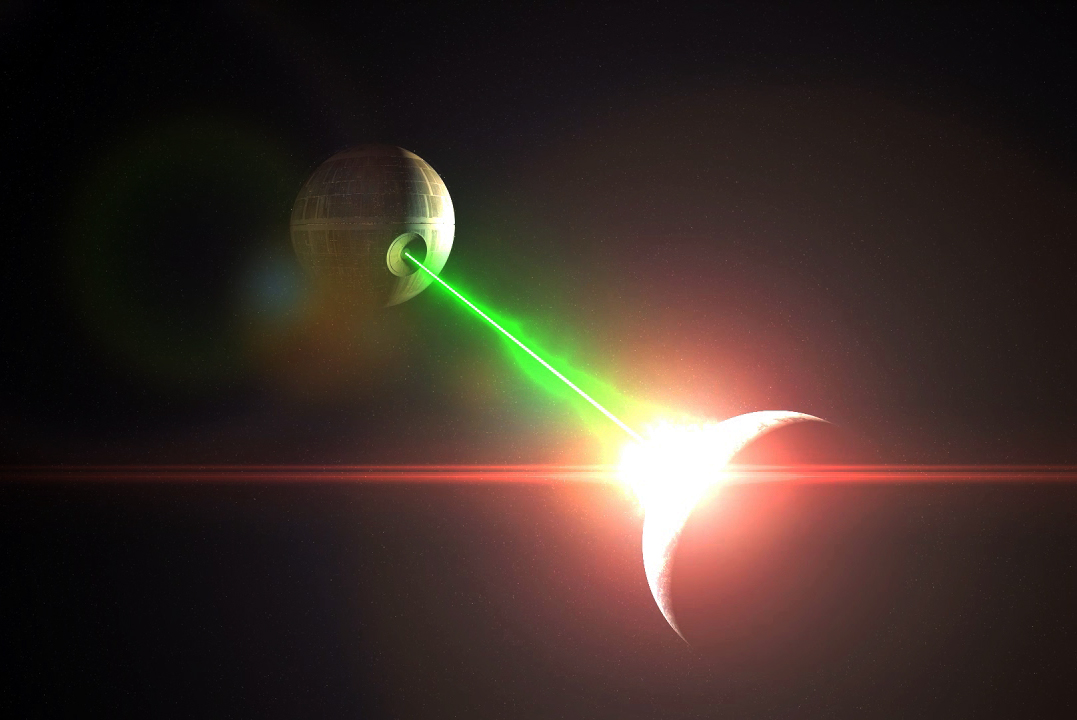

The Star Wars Consideration. I am not Darth Vader; I’m on Team Leia.

Interlocutor: You’ve got to be kidding.

Something to do with the “doing vs. letting happen” distinction? It’s one thing to not create a planet; it’s a different thing to destroy one. Now I know that it’s controversial whether this distinction is morally important. Consequentialists generally argue that it’s not, and try to explain away the intuition that it is, in terms of human squeamishness about “up-close and personal” interactions. I don’t buy those explanations. Experiments by Katya Saunders with young children indicate that kids mark the doing/allowing-to-happen difference, and its moral significance, in situations where there’s no physical contact with anybody. And John Mikhail has presented evidence that the Doctrine of Double-Effect is part of a humanly innate “moral grammar.”

Interlocutor: Interesting defense of Double-Effect (although it hardly follows from something’s being innate that it’s true), but the principle is completely irrelevant here. It’s true that destroying the planet would be an action, whereas allowing the planet to evolve would be a “letting-happen.” But this is an action that wouldn’t harm anybody! Double-Effect only comes up when the action under consideration entails a consequence that would be impermissible if intended directly—an action that causes harm. Taking action that prevents harm without causing harm ought to be a moral no-brainer.

Maybe I’m being too parochial about what constitutes “harm.” I have been assuming that the existence of harm depends on there being sentient creatures whose desires or interests are thwarted in some way. But maybe I’m confusing “harm” with the experience of harm. I don’t think that mosquitos feel pain, and that’s why I have no compunction about swatting them. But surely it harms a mosquito to kill it.

Interlocutor: Well, two things. First: we can stipulate that the killing of any living thing counts as harming that thing, but then it would be a separate step to say that all harming is morally wrong. And you, Louise, don’t accept that step! You take antibiotics when the doctor tells you to, and you don’t worry about the “harm” you’re doing to the bacteria!

Second: you are coming dangerously close to endorsing a view that you really don’t want to endorse, viz., that there is some inherent purpose in the universe as a whole. You don’t believe in purposes that are unconnected from creatures who have purposes. Of course, some will say that the “purposes” in question are determined by God. That’s OK for them, but you don’t believe in God. But come to think of it, it’s not OK for them, either: the thing about God’s purposes is that it is not always obvious what God’s purposes are; blowing up the planet could be exactly what God would like me to do. This same epistemological problem—which one would have to solve in order to solve the moral problem—besets any naturalistic translation of talk of “purposes.” Discovering that there is naturalistic value in the universe doesn’t tell us the specific value of that planet’s being there. So this is all going nowhere.

This just seems like too much responsibility. I’d feel better about destroying the planet if there were some sort of collective decision about it.

Interlocutor: Oh come on. It wouldn’t be OK if you did it on your own, but having—what, 100?—other people agreeing with you would make it OK?

Let’s back up—do I really have all the pertinent facts here? How can I be sure that life on this planet will evolve? Or that sentient creatures, if and when they turn up, will experience suffering? And also, how do I know that the explosion wouldn’t hurt other sentient life somewhere else in the universe?

Interlocutor: So now you are engaging in what you disdainfully call “philosophy-avoidance” when your students do it—you are refusing to accept the stipulations of the thought-experiment instead of grappling with the philosophical challenge it poses. Remember this the next time you bring up anemic violinists or out-of-control trolleys.

But if I blow up the planet, I’ll prevent the occurrence of a lot of good! Think of the frolicking squirrels that never will be, the great art, true love, ice cream (surely they’d invent ice cream!).

Interlocutor: All right, now we’ve come down to it. Despite your protestations that you don’t think it’s morally permissible to “balance” the goods of this Earthly life against the suffering of sentient creatures, it’s now emerging that you do think that the existence of some goods might somehow warrant the suffering it would entail in order for them to be realized.

Let’s get back, then, to the basis of your original intuition: What bothers you about many theodicies is the utilitarian assumption at their hearts: that the suffering of X could be justified by the good it provides for Y. Pace Derek Parfit, you don’t think that interpersonal tradeoffs between suffering and happiness are morally equivalent to intrapersonal tradeoffs across time. Moreover, the moral acceptability of tradeoffs of either kind often depend upon the fact that the agents in question have agreed to the trade. I agree to suffer reading through that last draft of your paper on conceptual engineering for the sake of your philosophical development—whether rational or not, that’s my choice. But the once-frolicking, now-terrified squirrel stuck in the jaws of a ravenous fox (whose own frolicking had just hours before provided me with enormous entertainment—video upon request) has hardly agreed to the arrangement.

OK, enough! Here’s where I’ve landed. I have a set of strong intuitions, none of which I’m prepared to give up, but that seem to entail a judgment about a hypothetical case that I cannot seem to accept. What do I do with that? There’s a name for the situation: I’m experiencing “moral dumbfounding.”

Philosophers who have discussed this condition disagree what to say about it: some think that the moral answers in these cases are obvious and that those of us who cannot accept them suffer from a psychological shortcoming that we should get fixed. Some philosophers think that moral dumbfounding shows that there is no objective answer to the moral problems that occasion it (or that there are no objective answers to any moral problems.) I don’t like either of those strategies. I’m a moral realist; I think the truth is out there.

What John’s ingenious puzzle (thanks, John, I suppose) has shown me is that I need to have the humility to recognize that, in this case, I have not found that truth, and that I may not ever find it. And it has also shown me that I need to be more generous to people who are dumbfounded by cases where I happen to have clear and consistent intuitions. This includes students who don’t know what to make of the aforementioned violinists and trolleys, but also fellow jury members, political opponents, vaccine skeptics—you know, other people.

But I probably won’t stop trying to figure this out, and neither should they (mutatis mutandis). That’s philosophy, and it’s for everyone.

(PS: Thanks, for real, to John Pittard for truly edifying conversation about this and other matters. He is not responsible for anything in the above that is stupid or wrong.)

Very interesting. I suspect that we are, at bottom, more life-affirming than rational…and that there’s an evolutionary explanation for that. If so, then it would be interesting to ask further whether it is the life-affirming instinct or the rationality instinct which should be curbed…and what the implications of either kind of curbing would be.

It seems to me that we are above all CONSCIOUSNESS-affirming, and that herein is also found the basis of a rational justification, in that consciousness is the chief value, or is the precondition of all values. I suspect that many would accept human life even if it necessarily meant a good deal of suffering – though not an infinite, or indefinitely extended, amount. Certainly we are grateful for the existence of painkillers!

I guess I have some mixed feelings about some of the above. Consider:

“Too much responsibility” – there’s a pretty good idea in the background here, I think, that seems to be presented in a strawman way in the response to the idea. In lots of cases it makes good sense to be less than sure of our own judgment. Often (not always, of course, but often) we can improve our judgment by consulting others and making decisions in a collective way. So, if it’s a case where I feel unsure or conflicted, or where it’s outside of my experience (as the ‘example’ is, of course) it might make sense to get the input from others. It’s obviously not sure-fire, and might be the wrong approach in some cases, but it’s not clear this is one. It seems to be dismissed too quickly in the face of bad criticism.

“do I really have all the facts?”/”I’ll prevent a lot of good” – I take both of these to be “fighting the hypothetical”, as law school professors say. But! Sometimes it makes sense to fight the hypothetical. This seems so in this case. Although we can say the words in the scenario, and sort of understand them, it seems less than obvious to me that we can really understand them. (This is so with lots of philosophy thought experiments, I’d say. Students often pick up on this in inchoate ways that we sometimes dismiss, but probably should work to help develop.) In such cases I don’t think it’s right to accept the (desired, often because baked in) “answer” to the problem. It makes sense to say we’re not sure, or to otherwise hesitate. (“If the world was very different than it is, it would be different” is a good inference, but it’s not clear it tells us all that much about the world as-is.)

BUT! It’s not clear to me that, say, vaccine skepticism is like this. Note that the example situation is not at all like a situation we have normal experience of. It’s not clear how we could know the things in question. (This might make us less sure of “our” claim at the start of the argument – that God should not have brought the world into being, if all the suffering was necessary for it, though we might still think it’s supported better than alternatives.) But vaccines (and some other things, like, say, the connection between gun violence and gun availability) are not like this. These things are supported by evidence in all of the normal ways. We might be wrong, of course, but we don’t have reason to think we are, and we don’t even have any strong reason to doubt it. In lots of these cases, if we were wrong, we’d have reason to doubt a lot of other things we take for granted. That again doesn’t seem similar to highly abstract and sparsely described philosophy thought experiments.

So, I’d agree that we should be hesitant to draw strong conclusions from some philosophical thought experiments, but it’s not clear to me how far this generalizes to other cases.

I think the reticence might have something to do with the fact that, at some level, you see the uniqueness of the young world and its eventual sentient beings, and that you would be snuffing out something that would inevitably be unrepeatable and unlike any other world, whether those other worlds contain sentience or not. Recognition of your own awful ability to wipe out the beginning of that life process, snuffing out the beginning of that life, halting the painstaking and eons long “work” that would go into that singular world, allowing it to eventually flower into one of those few that harbors sentient life and the value that comes with it just seems like murder of the young, so to speak. At some level you do see the pain and suffering as being the cost of that unique world, perhaps unavoidable, but you also see that the universe is richer with the world than without. So you allow it to continue.

Perhaps a relevant difference between the cases is that we suppose God could have done better? That his only choices are not this or nothing?

Thank you for this post Louise! I had a question about the case rather than the dumbfounding: is it supposed to be part of the stipulation that you know, of the potential sentient life on this planet, that it will suffer to more or less the same extent as the sentient life here on Earth? When you discuss the “do I really have all the pertinent facts” response, you sound like it’s stipulated that you do know that there will be comparable suffering, but in the description of the case itself, all it says is that sentient life will evolve “much as it did on Earth” – wasn’t sure if this was supposed to imply that the suffering would be comparable. In any case, if you don’t know this in the envisioned scenario, then your situation isn’t like the situation of an omniscient being trying to decide whether to make the universe. It could be that the uncertainty about the degree to which these sentient creatures will suffer makes a big difference to whether you ought to Death Star the planet.

On the other hand, if it *is* part of the thought experiment that you know there will be suffering of the same sort, I wonder whether you still retain your original intuition when considering a variant case in which the suffering is cranked up significantly, i.e., imagine that you know the sentient life on this planet will suffer far more than the sentient life on Earth. Do you still feel reluctant to destroy the planet in this situation? Thanks again!

How can I possibly know what it’s like to be omniscient in order to get this thought experiment off the ground in the first place? I know this sounds trivial but it seems an essential element of the thought experiment that I, literally and without fault, *know* everything that will happen on this world (the calculation depends on certainty, it becomes very different if the question is: sentient life might arise here and, if it does, it may have lives that contain more suffering than happiness – do you destroy it?).

I’ve written about problematically perspectival thought experiments before (they’re one reason why I’m skeptical of much vignette-based moral psychology) and I think the specific example in the guest post runs into the same sorts of problems that perspectival thought experimetns tend to run into (Matt L does a nice job explaining these and yet more problems). It feels like we can put ourselves into the position of omniscience but this is an illusion, we cannot (as Matt sense, our students often have an inchoate sense of dissatisfcation that tracks these problems) and when we have an intuition about these cases that intuition, I think, is really far off the mark of what we would think would be jusitifed if we actually found ourselves in that situation (assuming the situation where I become a deity while maintaining my own identity is conceptually possible in the first place).

So my own response here is that something has gone wrong but it’s not a case of moral dumbfounding. Instead it’s the thought that we can actually complete this sort of thought experiment in the first place.

My own thoughts concern the way the problem of evil is being formulated here, namely the antecedent:

“if the creation of our universe really necessitated the amount of suffering experienced by sentient creatures on this earth, then God would have had a moral obligation not to create it at all.”

If God is omnipotent then this antecedent is false. They could have just arranged things so that sentient beings do not suffer (or need to suffer in order to be motivated to avoid avoid harm, etc.) in the first place. The moral wrong lies in introducing the potential for any suffering at all, and for an omnipotent being, refusing to create sentient life does not seem at all necessary to avoid such a potential. I’m not an expert in this literature so someone correct me if I’m wrong, but this way of formulating the problem of evil seems immune to the reply from Pittard. To meet it you would need to argue either that a universe with suffering is better than a universe without one, or that God, while still omnipotent, is powerless to create sentient beings for whom suffering isn’t a feature of their lives.

I think the OP formulates the problem of suffering etc. in the way it does because it’s framed explicitly as the author’s reaction to “best-of-all-possible-world theodicies.” These presumably assume that the deity, for whatever reason, could not have “done better.” If one removes that assumption, then it’s no longer a question of “best-of-all-possible-world theodicies,” because it’s no longer the best of all possible worlds. (I have to acknowledge I don’t know much about this particular question though; I know the punch line of Candide, and not much beyond that.)

Ah, somehow I completely missed that phrase in the opening paragraph. But I think that just creates yet more cumbersome problems for the theist. And it also makes me somewhat confused about the constraints on the discussion: is the non-theist supposed to grant to the theist that this is the best of all possible worlds? Because it is not clear that Antony, by allowing that God could have created a world without any suffering, is granting that.

Does the suffering in question mean physical suffering (of various kinds) or psychological suffering as well? If the latter, then it may be worth considering that without psychological suffering there’s probably not going to be much “great art” (to lift a phrase from the post).

A Shakespeare who hadn’t suffered probably could not have written Hamlet, King Lear or the Sonnets; a Dostoyevsky who hadn’t suffered probably could not have written Crime and Punishment; a non-suffering Emily Dickinson likely could not have written some of her poems; etc. etc. etc.

In short, if you want “great art,” you’re probably going to have to accept some suffering in the world as part of the bargain, so to speak. So in this particular case it’s not a balancing, because they’re intertwined. (Or else you posit a quasi-utopian world without suffering where the meaning of the phrase “great art” will likely be understood differently.)

Thank you for commenting. I’ve a few thoughts here:

(1) I have doubts about whether an artist needs to suffer to produce “great art.”

(2) There is (I think) an underlying theory in your reply about how works of art are valuable that I am inclined to reject, namely that the world is just better for their existence.

(3) More to the point, I’m dubious that a world with suffering and “great art” is preferable to a world without suffering and no great art, or that it’s better an artist suffer and produce great art than that they not suffer.

(4) More locally, If given the choice to alleviate an artist’s suffering or allow them to suffer on the promise they’d produce great art, I’d choose the former option. (I’m assuming I don’t know what their wishes are on the matter, and also that it imposes minimal burdens on me to assist them.)

(5) While there is controversy about exactly what art is good for, I wonder if its importance would be diminished, and subsequently whether we would be worse off without it, in a world where no one suffers; the value of many things, including artworks, depends on contingent facts about human beings, including the fact that we suffer. In a world without suffering our needs would be drastically different, and the need for art may fall out of the picture.

Given further time to reflect on the matter, I might agree with you at least on some of these points. I was not trying to make a case for “great art” (though I think there is one to be made) but rather just trying to point to what seemed to be a tension here in the original post.

P.s. I also was not intending to claim that an artist *always* has to suffer to produce great art, and on some ‘modernist’ approaches the question would probably be deemed unimportant or irrelevant (though I don’t think it is).

Isn’t the relevant difference between you in the Darth Vader situation and God circa Genesis that God could have made a better world (less suffering) while you can’t provide a replacement for the world you’d destroy? I’m not sure how this thought experiment is supposed to undermine your original commitment once this asymmetry is pointed out.

As someone pointed out (and as I myself overlooked at first) this is a “best of all possible worlds theodicy” where god could not have done better—which makes me confused about whether Antony is accepting that condition, if a world without suffering is supposedly better.

This is a wonderful post, Louise (if I may). The thought experiment and discussion are indeed very interesting, but I want to get back to the broader point you’re making here rather than the example you use to make it.

You say, “But I probably won’t stop trying to figure this out, and neither should they (mutatis mutandis). That’s philosophy, and it’s for everyone.”

I agree completely. Our moral feelings can point in all sorts of directions, but seem to be disturbingly affected by our social environment. Slavery, genocide, indifference toward the suffering we cause to nonhuman animals, and just about anything else need not cause us any moral discomfort at all. We know this because we have seen entire societies that found all these things to be normal and even worthy of moral defense. What changes things is the discovery of something that just doesn’t quite fit, some basis for doubt, some glitch in the story. And the process that leads from the discovery of the glitch to reasonable social change (as opposed to the mere replacing of one damn thing with another, i.e. drift) critically depends on people who succeed in pointing to the glitch emphatically and clearly enough for the problem to become a real source of irritation. (Depending on one’s audience, this irritation will require more or less emphasis to be felt).

The interlocutors who engage with one another over these things — the ‘conservative’ one coming up with interesting reasons why the thought experiment (say) doesn’t present any real problem, and the ‘dissenting’ one finding ways to show that the thought experiment is still troubling after all, or to come up with new thought experiments — are both doing philosophy. (I’m using ‘conservative’ here to mean supporting the default answer: what counts as conservative in my sense changes with the dominant norms in the culture or subculture). Both sides may engage in a great deal of motivated reasoning, but the system can handle it if there are enough sharp-eyed people on the other side to apply rational pressure, and if enough people care about the integrity of the process: who are more interested in the fairness of the courtroom than the outcome of the suit.

With proper norms in place, and a proper concern for principle, philosophy can work its way through all sorts of bad arguments and positions and come out right in the end. As you point out, there are places where the resources of the defender seem to dwindle to nothing: this is where dumbfounding sets in and the doorway to moral or political improvement (or perhaps the restoration of what has always been right) at last appears. Even if nothing is conceded at first, the fact that nothing could be said in defense of the moral intuition will continue to be an irritation, provided that the objection is not allowed to be forgotten or shut out of the discussion.

But, as you mention, those who have been fighting to deflect the criticism and now find themselves with no response to make may instead choose some rule-breaking or rule-evading moves. For instance:

The non-philosophical response. E.g. ‘Yes, I grant that the arguments we’ve considered for the retention of the current practice of slavery all seem to fail on intellectual grounds, and what our side is left with is nothing more than a moral feeling that slavery is justifiable. But we won’t let that bother us, because

– there is obviously disagreement on this issue, and where there’s disagreement, there is no objectivity and hence no truth, so it’s all just a matter of opinion;

– this is just not the sort of issue anyone in the dominant social group within philosophy cares that much about;

– etc.’

The anti-philosophical response. E.g. ‘Look, I’m sure you can sit there all day and come up with quibbles that raise doubts about the possibility or importance of animal suffering. But maybe, instead of doing so, you should catch up on the vast literature that the rest of us have agreed on (in which arguments on your side of the issue are treated about as seriously as I’m treating you now). Or, better yet, maybe you should just open your eyes to what’s right in front of you. If you haven’t yet come to see things my way, you have clearly not yet attended to the obvious moral reality I perceive, from which it follows that your objections are not worth taking seriously,’ etc.

The destruction-of-philosophy response. E.g. ‘Genocide in this case is morally permissible, and anyone who denies or doubts this is therefore an enemy of morality. Anyone who dares to stand as an enemy of morality must be shamed, punished, and banished from the public sphere. Let us, therefore, shut down this back-and-forth at once, especially during these troubled times when what we need is moral clarity. And let any person, group, or forum that allows the discussion to continue also be shamed or otherwise coerced into silence.’

These last three moves, presented in order of how grave a threat they present to philosophy, may become more recognizable if one alters the topic and/or sociopolitical valence. But it strikes me as odd that they are not always recognized as different in kind from legitimate philosophy.

The presentation of a troubling counterexample, and the ongoing battle between those who come up with distinctions that show that the counterexample doesn’t apply or some restatements of it that show that it does, all does the work of philosophy by moving us closer to a point where one side faces moral dumbfounding (or its equivalent), or else the other side sees that the push toward that point cannot be effective with the supposed counterexample.

Once the state of dumbfounding has been reached, the philosophical work continues as the dumbfounded side continues to spin its mental wheels, trying to find some way out of the predicament. But the longer one is forced to sit and acknowledge the lack of justification, the weaker the moral conviction should become (to a serious and committed philosopher, that is). It may take a very long time, but some pretty significant moral intuitions have left us both personally and as a society when there turned out to be nothing to say for them.

It seems to me now that the line demarcating a philosophical mindset from one that isn’t philosophical depends on this: Pushing toward or against the point of moral dumbfounding in a principled way, or stewing in the juices of moral dumbfounding, counts as philosophy. Derailing that process from outside of the process, or saying that it doesn’t matter or that it’s positively bad to engage in it, is something else that philosophers should unite against: what we have in common is our practice and its goals. And taking dumbfounding seriously is something that no philosopher can avoid.

I’ve always thought that that setups that assume perfect knowledge of the future, and indeed multiple possible futures, are sufficiently different from the human condition as to be irrelevant for evaluation of human ethical judgements. Imperfect information is essential to us.

But then I was never in the least tempted by any sort of utilitarianism.

Right.

I agree that setups that assume perfect knowledge of the future, or multiple possible futures, are sufficiently different from ordinary cases to be useful judgments for evaluating theories. But I’ve never been tempted by any *non*utilitarian ethics.

Really? The infinite ethics stuff doesn’t worry you at all? Or the non-identity problem? Or the fact that it entails that most abortions are grievously wrong? Or the idea that we’re morally required to choose an option that involves rape and murder just because it produces slightly more net value than the alternative? (Of course, it will have to produce significantly more gross value to make up for the disvalue of the rape and murder.) Sorry, this is probably not the place for this, and you were probably exaggerating anyway, but I can’t understand how so many philosophers are such unwavering consequentialists. Maybe, in the end, consequentialism is the best view. But everyone should be tempted by the thought, and hope that it’s true, that there is a better alternative.

For a contrary view: “I argue that (something close to) utilitarianism is actually the most intuitive moral theory, because (i) its conflicts with intuition are shallow, and can generally be accommodated at least reasonably well by appeal to related moral considerations such as character evaluations; whereas (ii) non-consequentialism conflicts with our intuitions about what matters in ways that are deep and irresolvable.“

Perhaps you’ll disagree with my arguments. But if they’re right, they could neatly explain why “many philosophers are such unwavering consequentialists”.

I can’t speak for Kenny, but I’m not exaggerating when I say that I’ve never been the slightest bit tempted by non-consequentialism. Sure, for any specific view, we might always hope for a “better alternative”. But non-consequentialism strikes me as both utterly hopeless and deeply unappealing, for the reasons outlined in that post.

(That said, I don’t expect everyone to agree with me. People are a diverse bunch, and some find the strangest things appealing!)

As a non-philosopher, I’m a little puzzled about why philosophers use the language of “consequentialism” and “non-consequentialism.” As Rawls observed quite a long time ago, “[a]ll ethical doctrines worth our attention take consequences into account in judging rightness.” (TJ, 1st ed., p. 30)

Louis: consequentialism is standardly defined as the view that consequences are the *only* thing that matters in judging the rightness of actions; you are correct that most doctrines allow that consequences matter at least to some extent, in at least some cases.

Richard: I read the blog post but didn’t watch the video. A couple of comments. First, what does it mean for an intuition to be “shallow”? I mean, I really firmly believe that it is wrong for a utilitarian sheriff to hang an innocent man to prevent rioting or whatever. My credence in that is close to 1; I don’t know how “shallowness” is supposed to enter into the calculation. (And I don’t think the sheriff has “more reason” to do that either.) Second, I’m not sure how “By contrast, I think it is much clearer that (e.g.) innocent people’s lives are more important than deathbed promises” is supposed to support consequentialism. That sounds like an axiological claim, one that consequentialists could, in principle, reject, and that non-consequentialists could, in principle, accept. In fact I do accept that claim. Third, you don’t address the infinite ethics problem, which seems to just break consequentialism, no? (If the world *is* infinite, at least.) Finally, as regards your overall methodology (this is related to my second point I guess), many views start with an axiology, and then move to principles that take you from the good to the right, and then live with the results, as long as they’re not too implausible at least. (Maybe you and I agree about axiology, but I deny that we should maximize the good, holding rather that our duty is merely to not destroy or prevent the existence of any goods. That will have some implausible entailments, but so does the consequentialist route!) So I don’t see that there’s anything distinctive of consequentialism about your general approach. Huemer may have advocated an alternative strategy, but I would be surprised if you’re not both using some version of RE, perhaps with different starting points.

Why would you think that? I would think that moral principles are necessary, and so hold true across all possible worlds, so if they fail to get the right answer in some very unfamiliar possible world, this can falsify them as much as if they did so in a realistic world. Or do you mean that our judgments about such worlds are unreliable?

– either destroying or continuing Planet Earth makes no sense in any case as humans who are now most developed species might have evolved for absolutely no reason but by a purposeless accident and so whatever above strategy one uses there’s then no actual reason for either as there’s probably no existing purpose to do anything at all –

For those interested in the literature on the problem of evil, Justin Mooney presents a case very much like the one Pittard gives and uses it to make a similar point on pp. 453-454 of this paper, published in Faith&Philosophy.

https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol36/iss4/2/