CNRS Commission Defends Roques in Response to Plagiarism Accusations / Update: Roques Dismissed from CNRS (updated)

A commission formed by the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) has issued a statement defending a researcher in medieval philosophy against multiple charges of plagiarism.

Last fall, several articles by Magali Roques were retracted owing to them containing passages copied from others without attribution (details here). A commission composed of “three experts in the field, all foreigners” [see update 7, below] was tasked by CNRS to investigate, and the results of that investigation have recently been made public by CNRS.

Using a conception of plagiarism according to which plagiarism “signifies above all the theft of another author’s whole argument or the structure of their work or their fundamental ideas,” distinguishing between “plagiarism” and “unacknowledged borrowings,” and noting that they were unable to discern in Roques’ writings “a wish to appropriate anyone else’s ideas or of an intention to deceive the reader about the origin of the ideas put forward in the articles,” the commission concludes that though they are “seriously flawed by the regular presence of bad scholarly practices,” her writings contain “neither academic fraud nor plagiarism properly so called.”

Here are the commission’s “primary findings” (the report refers to Roques as “MR”):

-

- The results of our qualitative analysis show that there is neither academic fraud nor plagiarism properly so called in MR’s English articles. Moreover, there is no sign to be found of a wish to appropriate anyone else’s ideas or of an intention to deceive the reader about the origin of the ideas put forward in the articles.

- The results of our quantitative analysis have shown that the proportion of unacknowledged borrowings is relatively limited—sometimes even minimal—in comparison to the total size of each article. Admittedly, a brute calculation of the passages borrowed by MR from third-parties

would tend, at first glance, to justify the accusations made against her. A more careful calculation, however—one which, in particular, takes into account the nature of the borrowings, has shown that in a number of cases it is not a matter of undeclared borrowings in the strict sense. Once the Commission had thus come to realize that many passages had been wrongly accused of being plagiarized, the proportion of borrowings open to accusation in the various articles became considerably smaller. - The qualitative and quantitative analysis of the publications under accusation has led the Commission to reach a dual conclusion. On the one hand, it is undeniable that MR has been the victim of an injustice, because her accusers have fashioned and diffused, wrongly, if not with ill intent, the shameful image of a ‘serial plagiarist’, who composed all her writings simply by copying what others have written (see ‘Philosopher Revealed as serial Plagiarist’ [multiple updates], Daily Nous). On the other hand, it is also equally undeniable that the whole body of work in English published by MR is seriously flawed by the regular presence of bad scholarly practices, by what might be called a sort of active negligence, which, although not a matter of academic fraud, cannot be excused.

- In her publications in English, MR has quite clearly lacked rigour in her way of making references and has not respected the academic standards accepted in the area. These publications suffer from serious, persistent negligence in the manner of referring to the secondary literature and sometimes also in references to the sources. In these articles, MR has therefore failed to keep to the requirement for a scrupulous and irreproachable method of work, which every researcher should observe.

- In her defence, MR cites various reasons to explain the deficiencies noted in her articles in English. Some of them (such as ‘youthful errors’ and a lack of awareness about plagiarism) did not do much to convince the Commission. The Commission did, however, accept her lack of assurance in writing English as a credible reason for MR’s frequent borrowings of technical terms and formulations from authoritative studies published in the Anglophone world. Moreover, trying to forge an academic career in an ever more competitive world, MR seems to have engaged in a race to publish, writing many articles in English at breakneck speed, but cutting corners in a number of her publications, in the method, quality and rigorousness of her research. The Commission accepts that MR’s explanations are sincere and in good faith, yet it wishes to emphasize strongly that unacknowledged borrowings, even if they are accidental, involuntary or incidental, are unacceptable according to the academic standards recognized in the area.

- The accusations of plagiarism concern the publications which were written in a limited period, during which MR was trying to make a place for herself in the Anglophone academic world. It is exactly in this specific context that there occurred the failings that mark the articles in English. It is fitting to observe here that, before they could be published, all these articles were subject to peer review and that, in most cases, the reviewers came to very positive judgements both about the contents of the articles and the originality of MR’s contribution to the subject: judgements which convinced the editors of the academic journals in question who, although they are specialists in the area, did not notice the slightest indication of failings in these works.

- The Commission notes that, in the great majority of cases, the unacknowledged borrowings discovered in the various articles occur in the parts which introduce the general area being studied, which put the questions treated into context and in syntheses about authors who are introduced by way of comparison. These borrowings do not have anything to do with either the general interpretation or the main arguments developed by MR in her works. Each of the articles examined thus presents an individual contribution of her own by MR, with her own original ideas, based on which she presents distinctive views, which she offers to specialist readers in order to engage in academic discussion among equals.

- The Commission did not discover any academic fraud or any sign of plagiarism in the three French publications. The accusations regarding these publications turned out to be to a large extent unfounded. There is, indeed, the borrowing of a phrase from an article by Irène Rosier-Catach, but the passage in question merely states a commonplace. That said, the Commission notes that MR’s negligence over giving references is also found to some degree in these articles.

- The Commission observes that the idea of plagiarism goes far beyond tacit citation: it signifies above all the theft of another author’s whole argument or the structure of their work or their fundamental ideas. Nothing of this sort can be attributed to MR.

- Finally, the Commission wishes to give an explicit reply to the question of whether ‘supposing that the borrowings had been correctly cited … the articles under accusation contain enough original ideas of MR’s own to justify their publication.’ It can indeed confirm that if MR had cited all her borrowings correctly, this would not have lessened the number of original ideas that she proposes in the articles under accusation. The publication of these articles would therefore be entirely justifiable if MR put her borrowings into inverted commas and attributed them correctly to their authors.

In line with the claim that the publicization of the accusations of plagiarism against Roques constitutes “an injustice” (see #3, above), the commission writes:

the vast damage done to MR’s academic standing by the accusations of plagiarism seems already to outweigh in severity any sanction proportionate to the deficiencies and mistakes considered during our enquiry.

The commission also notes that it is not up to them “what course of action the CNRS should take in response to this affair.”

You can read the commission’s entire report here.

* * * * *

I think I should respond to this passage, from #3, above:

It is undeniable that MR has been the victim of an injustice, because her accusers have fashioned and diffused, wrongly, if not with ill intent, the shameful image of a ‘serial plagiarist’, who composed all her writings simply by copying what others have written (see ‘Philosopher Revealed as serial Plagiarist’ [multiple updates], Daily Nous).

While I appreciate the commission not ascribing to me any ill-intent, I will note that this passage appears to contain two mistakes.

First, the commission takes the term “serial plagiarist” to be an error. To the contrary, in ordinary academic practice, “plagiarism” includes the very kind of behavior that led to the retraction of multiple articles by Roques; and indeed, several of the editors of the volumes responsible for the retractions expressly identified plagiarism as the reason for them. My failure to use the commission’s own peculiarly narrow conception of plagiarism, for which it provides no support, does not mean that I’ve wrongly described what has happened.

Second, no one (to my knowledge) at any point said that Roques “composed all her writings simply by copying what others have written.” That is not only a false account of the accusations against her, it is disrespectful to the editors and others who took the time and energy to painstakingly research, detail, and annotate the specific copied passages, communicate and deliberate about what to do in regard to them, and institute and announce the retractions. This is not a trivial amount of work, and it was quite clearly in evidence in the original Daily Nous post about this and its updates.

Though the commission is mistaken in its own account of whether and why there has been an injustice, it is still possible that there was an injustice. After all, it’s certainly possible that having true things said about one may constitute an injustice, particularly given the reach and seeming permanence of things said on the internet. If someone wants to make the case that that is what has happened here, I’ll listen.

UPDATE 1 (6/26/21): Some minor edits were made to this post, including a change to the headline to make it clearer that it was a commission tasked by CNRS (and not CNRS itself) that conducted the investigation and wrote the report.

UPDATE 2 (6/28/21): “The CNRS report is a fig leaf that doesn’t quite cover up” — a quote from Michael Dougherty (Ohio Dominion) in an article on the story by Retraction Watch.

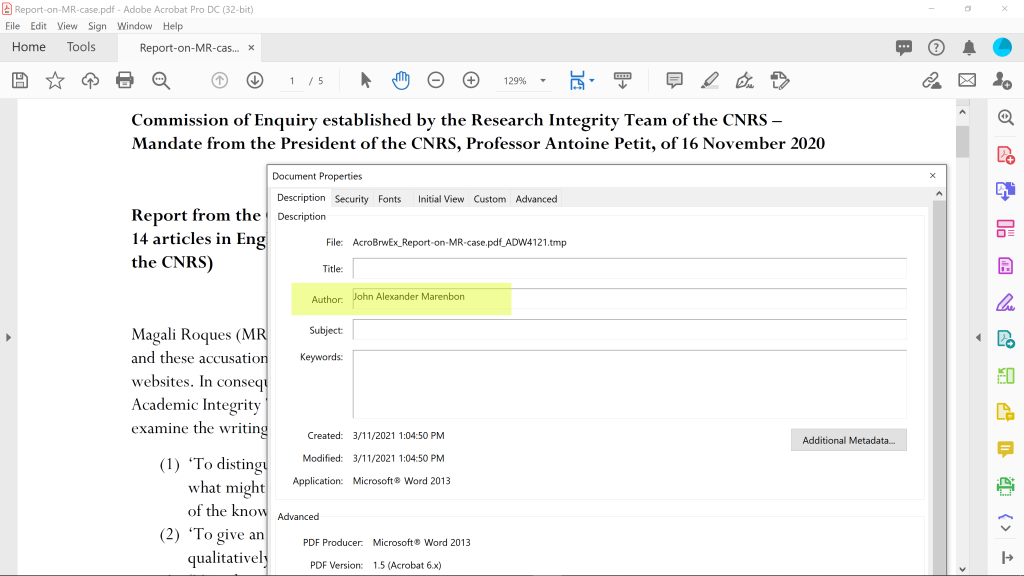

UPDATE 3 (6/28/21): CNRS did not announce the names of the “three experts in the field” that comprised the commission that investigated and reported on the Roques matter, but a reader pointed out that the metadata of the PDF of the report lists John Marenbon of the University of Cambridge as an author:

While it is unclear that the commission should have been anonymous to the public in the first place [see Update 7, below], it is rather noteworthy that the state research agency of France apparently failed in such an elementary way to protect that anonymity.

UPDATE 4 (6/28/21): An early-career French philosopher who wishes to remain nameless emailed me a lengthy comment, which I post below with their permission. This person asked me, for reasons expressed in their email, to relax the requirement that commenters on this post use their real names. I’ll accede to that request. Commenters on this post may use pseudonyms; don’t use “anonymous” or “anon” (etc.) in your handle. Whatever pseudonym you pick, use it consistently should you comment more than once on this post. Pseudonymous comments must be submitted with real, verifiable email addresses (the email addresses will not be made public).

First, I want to thank you for covering this story. As you might have noticed, the French philosophical community has been almost entirely silent on this—at least when it comes to social media. There are probably many causes for this silence, but one of them is to be found in the fact that the French philosophical community is quite small and very clannish. This clannish character leads to a system in which people are very likely to retaliate against anyone who criticizes a member of their clan. There is nothing to gain, and much to lose, in calling out even clear cases of academic fraud. People are simply afraid to speak up, so they shut up. I know for a fact that this is my case, and the case of other French researchers—particularly researchers without a permanent position. Because we hope to find eventually a permanent position in France, we keep quiet even when outrageous cases like this one happen in plain sight (11 retracted articles!!!). I know of the case of someone who shared links to the Daily Nous post on this story. They have been explicitly criticized for this by senior researchers. There are genuine attempts at making this story disappear. It might be out of good intentions—for example, an intention to avoid hurting the plagiarist herself, whose reputation has suffered and who, I suppose, must have been through some genuinely difficult times because of this story. However, at the end of the day, the result is some sort of mafia-like suppression of the truth.

So, I am grateful for your covering of this story. If it was not for foreigners (who have nothing to lose, as they are not as dependent on the goodwill of the French academic establishment), this story would have been completely silenced. No one would have heard of it outside of a small circle, and people would have been silenced when trying to speak about it…

Second, I want to point out that your comment policy on your post at Daily Nous can be quite frustrating for people in my position. I would like to express my opinion—not to insult M. Roques, whom I do not know personally and with whom I can even empathize—but I feel like I cannot, because if the wrong person in France saw my name there, this could very well destroy my chances of ever finding a permanent academic job in France. Enforcing a “real name only” comment policy in this sort of case, with a clannish system of retribution-punishment-omerta in the background, is tantamount to preventing most people from speaking their minds. (A strong moderation policy, on the other hand, to avoid any sort of insults, would be perfectly justified, although I understand that it might be too time-consuming).

UPDATE 5 (7/4/21): I’ve been informed by multiple sources that Roques has been dismissed from CNRS.

UPDATE 6 (7/9/21): The Commission writes (in #8, above), that they “did not discover any academic fraud or any sign of plagiarism in the three French publications” they examined. I’ve now seen text analyses of these three articles and they indeed contain plagiarism, including passages that were plagiarized from English-language sources and then translated into French for uncredited insertion in the articles. Note, too, that MR pubished more in French than just the three pieces examined by the Commission.

UPDATE 7 (7/13/21): In light of CNRS’s inadvertent release of the names of one of the members of the commission (see Update 3, above), the other members of the commission requested their names be made public. The commission was composed of Ruedi Imbach (Emeritus Professor of Medieval Philosophy, Sorbonne University), John Marenbon (Senior Research Fellow, Trinity College, Cambridge, Honorary Professor of Medieval Philosophy in the University of Cambridge and Visiting Professor at the Università della Svizzera Italiana), and Tiziana Suarez-Nani (Professor of medieval philosophy, Department of philosophy, University of Friborg / Switzerland).

UPDATE 8 (7/20/21): The board of the Société Internationale pour l’Étude de la Philosophie Médiévale, an academic organization dedicated to promoting the study of medieval thought, has, “due to recent discussions in and about our field,” issued a statement about plagiarism. It asserts that plagiarism should be understood as “appropriating wordings, images, or ideas from someone else, intentionally or unintentionally, without explicit acknowledgement of the extent and nature of the appropriation and without precise bibliographic reference to its source.” You can read the whole statement here.

UPDATE 9 (7/23/21): Another retraction. “An Introduction to Mental Language in Late Medieval Philosophy,” a chapter by Magali Roques and Jenny Pelletier in The Language of Thought in Late Medieval Philosophy: Essays in Honor of Claude Panaccio, a volume they edited for Springer’s Historical-Analytical Studies on Nature, Mind and Action book series, has been retracted. The retraction note says the reason for the retraction is “significant textual overlap with a number of sources,” and notes that “Magali Roques accepts responsibility for introducing this overlap into the text.” The sources include works by: Joël Biard, Susan Brower-Toland, Richard Cross, Catarina Dutilh Novaes, Russell L. Friedman, Russell L. Friedman and Jenny Pelletier, Axel Gelfert, Joshua P. Hochschild, Peter King, Gyula Klima, Simo Knuuttila and Juha Sihvola, Calvin G. Normore, Gabriel Nuchelmans, Claude Panaccio, Stephen Read, Sonja Schierbaum, Juhana Toivanen and Mikko Yrjönsuuri, and Ria van der Lecq.

UPDATE 10 (9/12/21): The editors of the philosophy journal Bochumer Philosophisches Jahrbuch für Antike und Mittelalter, Manuel Baumbach and Olaf Pluta (both of Ruhr-Universität Bochum), wrote an editorial in which they reveal that an article they published by Roques contained multiple instances of plagiarism. The article is “Metaphor and mental language in late-medieval nominalism.”

Strangely, the journal has not retracted the article. Instead, it published a list of the plagiarized passages along with citations that ought to have accompanied them. The list was supplied by Roques, the person who committed the plagiarism, and approved by the editors, who apparently missed the plagiarism the first time around; and so, even at six pages long, readers may have their doubts about the completeness and accuracy of the list.

The editorial, dated December 28, 2020 (though only recently posted online) states that it and the corrections “will be available together with the electronic version of the article.” As of this update, neither of the two pages listing the title and abstract of the article (here and here) mention or link to the editorial or the corrections. The publisher of the journal is John Benjamins Publishing Company.

The sources plagiarized in this particular article by Roques include Raymond W. Gibbs, Jr., Catarina Dutilh Novaes, Irène Rosier-Catach, Mary Sirridge, Georgette Sinkler, E. Jennifer Ashworth, Richard D. Johnson Sheehan, David L. Thompson, Ria van der Lecq, Sonja Schierbaum, Jack Zupko, W. Grey, Marilyn McCord Adams, J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Frédéric Goubier & Nausicaa Pouscoulous, Peter Adamson, Eva F. Kittay, and Sean Driscoll.

UPDATE 11 (1/21/22): Another Roques article has now been retracted on account of plagiarism: “Quantification and Measurement of Qualities at the Beginning of the 14th Century. The Case of William of Ockham,” which appeared in 2016 in Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale. In an note, the editors write that the article “presents numerous instances of plagiarism, in the form of

the unreferenced appropriation of sentences and views drawn from previous scholarship.” They add:

The Journal, in the person of its directors and of the editorial Board as a whole, resolutely condemns any form of plagiarism, such as the one exemplified by the article in question, as much as any other form of scientific communication that involves the unreferenced and so illegitimate appropriation of other scholars’ writings or ideas.

Those plagiarized in this piece include: Susan Brower-Toland, Paolo Cantù, Richard Cross, Matti Eklund, Stefan Kirschner, Marilyn McCord Adams, Erwin Neuenschwander, Chris Schabel, Jean-Luc Solère, Curtis Wilson, and Rega Wood.

Comments must be submitted with a verifiable email address.

Please avoid insults, speculations about people’s character, and the like in your comments.

See the Comments Policy for more details about commenting at Daily Nous.

Comments on this post are moderated and may take some time to appear.

As Peter Kivy once observed (see what I did there?), you don’t need to have the concept of a catamaran to build one (or, indeed, the intention to build a catamaran); you just have to try to stabilize your canoe with outriggers.

The same seems true of plagiarism to me; the question of whether someone had nefarious intent is not all that relevant. This is how I think about student work, too, which only sometimes demonstrates clearly nefarious intent but more often reflects ignorance (willful and otherwise). It’s still plagiarism, and I mark it accordingly. (Now, granted, the consequences may differ depending on what I think happened.)

In this case, the fact that the “borrowings” are “borrowings” and undeclared really seems to count against the conclusion in (1). There is, after all, some evidence of appropriation and deception–namely, the fact that sentences and passages were lifted wholesale from other sources without attribution. Whether that amounts to evidence of wishes or intent is, again, kind of immaterial (although personally, I’d say it’s de facto true).

The account of plagiarism offered in (9) is not in accordance with my understanding or application of the term. Again, the test is the classroom: if I’d discovered this in student work, it would have earned a zero for plagiarism and a chat. I got busted for doing this sort of thing in an essay on the International Space Station in grade six. If it didn’t pass muster in an elementary school classroom (and rightly so! Thank you, Mrs. Smith!), it shouldn’t pass muster in a professional academic context, either.

Franchement, c’est honteux.

« Recourant à une conception distinguant ‘plagiat’ et ´emprunts non reconnus’ ».

Mauvaise foi, novlangue ou génie juridique? Il y a quelques années, j’avais eu droit à « simples coïncidences » suite à une saisine pour plagiat. Sacrées commissions, va 👍

I find the report very strange and unconvincing. As if the experts were focused on defending MR at all costs. They adopt a very “relativist” stance towards plagiarism. What is the sense in such a research practice when you can just copy a fragment of some other text and incorporate in into your own? Maybe history of medieval philosophy would work better with bots in charge instead of humans? Just joking. Or maybe not?

Lulz, the shit I just took this morning has more intellectual integrity than the CNRS. It’s good to know that in France, you can get away with rampant plagiarism if you are sufficiently well-connected and famous.

Have you tried adding fiber?

Jason Brennan, I hope that since you posted your comments you have taken the time to read the comments of “French scholar” and “Parisian Medievalist”, which provide some important factual information.

If this is the case, you should retract your statements and apologise for speaking without sufficient knowledge of the case.

If not, there is still time to read the comments in question.

It would be helpful to know whether the description of plagiarism by the Office of Research Integrity and by the CNRS’s Ethics Committee captures what is ordinarily meant by plagiarism by those of us who write in medieval philosophy. Is their description adequately understood by the report? Is the understanding of plagiarism in philosophy or maybe intellectual history different from that in some other disciplines, such as the sciences?

As a scholar of medieval logic, and as an academic philosopher teaching undergraduates about plagiarism, I do not recognise the definition of plagiarism that the report uses. It falls far, far short of the standard to which students are held across academia, and it falls short of the standard to which I would want my fellow medievalists to be held.

The definition on p. 24 of the CNRS Ethics Committee guide ( https://comite-ethique.cnrs.fr/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/GUIDE-2017-FR.pdf ) has this, which seems closer to the common usage:

“Le plagiat consiste en l’appropriation d’une idée ou d’un contenu (texte, images, tableaux, graphiques…)”

Hi Justin, It’s commendable to have asked the commentators not to be anonymous. I just wanted to let you know, though, that many French early career researchers are scared to even mention the topic in public (I myself received some pressure not to speak about it). Thank you for writing these articles, because nobody will do it in France. CNRS has also taken a public stance against Pubpeer, just so you know. Denouncing fraud in France seems worst than committing it in the first place. There is something rotten, it’s quite frustrating.

Anyway, sorry for making you moderate this comment. Have a great day.

talking here only about medieval philosophy: couldn’t agree more with the description of the Parisian/French mafia-like system, but one should not forget that the vast majority of those who are in the CNRS are honest, serious scholars. OK, not all of them! Indeed some (big or relatively big) names are not (yet?) mentioned publicly, but as someone here wrote, we know them – it’s been a while since the clanish style became the norm, dismantling it it’s complicated, and, as we just saw, it would maculate big names from the UK (and the US), part of the same network.

The CNRS committee is right in stressing one point: MR did not plagiarize ideas, but words.

I am not a member of the committee, but I already pointed this out under Justin’s first post on the issue, not to excuse the evident plagiarism, but to stress that she simply did not need plagiarizing others to write good papers, which makes the whole story even more sad.

not sure I share the same view, precisely the one that MR wanted to distribute in her defence, but which cautions a dangerous practice. Phrases (i.e. words) transmit ideas, she did not choose to copy the acknowledgements or other banalities.

Take her ‘Contingency and Causal Determinism from Scotus to Buridan’ (see the posthttps://dailynous.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/roques-magali-contingency-causal-determinism-plagiarism-mark-up.pdf) there is hardly one sub-section of the paper without passages copied from others – her contribution to the this paper was to connect these passages and write the abstract (the proofs given in Vivarium are also convincing).

I’m not clear on how one can copy someone else’s words, tweaking them slightly, without thereby copying their ideas; what is it that words express, if not ideas?

All this is very troubling.

> The Commission did, however, accept her lack of assurance in writing English as a credible reason for MR’s frequent borrowings of technical terms and formulations from authoritative studies published in the Anglophone world.

MR is not the only person who is not a native English speaker in a preeminently English-speaking academic world. She is also not the only one “in a race to publish”. The report seems to imply that if we are unsure about our language skills and nevertheless want to publish a lot (who isn’t, and who doesn’t?), then that gives us license to “borrow” texts. Even if these texts were not essential to MR’s arguments, it is still as if in a marathon race one of the winning participants took a 10k shortcut and the organizers said “OK, she was just getting tired.”

I think this is indeed an important point which receives no coverage in the report. It seems to me that it is ethically significant whether these actions gave MR an undue advantage against other candidates. There is a significant case that this was the case, since non-native English speakers who did not cut corners probably had a shorter list of publications, given the extra time needed to write articles legitimately from scratch. I think there would be grounds to think that such a copy-paste approach probably would even giver her an unfair advantage over a native speaker. Even in my first language, I find that it takes me time to formulate my ideas and figure out how to articulate them grammatically/syntaxically. Besides, treating the “ideas” or “arguments” as separate from the “rest” of the text seems hard to justify, perhaps especially in philosophy. If a student of mine gave me a paper which was not a paper but, say, a diagram of all of the parts of the arguments and their logical connections, I would not accept it, because that is not “sufficient”. This, to me, points to the fact that the “form” (for lack of a better term) is an integral part of a philosophical work, and not just the ideas themselves, if we grant (which I think is doubtful) that ideas can even be neatly separated from the rest of the text in such a way. There are also philosophers that owe a great part of their renown to their especially keen way of presenting their arguments, rather than just the arguments themselves.

1-Le culot! (the audacity? The chutzpah?). I read the report and it did not feel good. Some parts amazed me. For example, the report claims that uses by M.R. of publicly available translations of medieval authors does not count as plagiarism, even if she omits to mention the name of the translators (“Published translations of medieval authors, which are thus in the public domain. Omitting the names of the translators is clearly negligent and goes against accepted standards of academic behavior”). But this is simply NOT what M.R. seems to have done, if I believe the analysis given in this document (see here for example note 60: https://dailynous.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/roques-magali-contingency-causal-determinism-plagiarism-mark-up.pdf). She wrote “my trans” for allegedly plagiarized translation of dozen of lines of text, which is MORE than merely omitting the name of the real translators. If this document states things correctly, that means that she explicitly appropriated translations (and did not just fail to mention the real translators), which in my book (in everyone’s book, I hope?) counts as plagiarism. Three main possibilities: either the analysis given in the above document is deeply faulty, or the commission was seriously and deeply mistaken, or the commission lies.

The core of the exonerating report relies on a distinction between “unacknowledged borrowings” and “plagiarism”. On that, a few things. First, the letter of the director of the CNRS asked the commission to decide in their report whether M.R. had committed “plagiarism” or had simply borrowed “formulations”. Charitably and reasonably interpreted, “borrowing of formulations” would refer to the borrowing of a few expressions, groups of words, at most a few short sentences here and there – obviously NOT to full paragraphs. The commission then used this distinction, changed it (dropping the “formulation” bit entirely in their report) to create a distinction that I find amazing between “unacknowledged borrowings” and “plagiarism”.

Second, this distinction, as it is made and used, is, to me, mind-blowing. I genuinely do not understand how any competent and self-respecting scholar could draw it – particularly in print. I take it that we would all have a good laugh if one of our students would come to us, justifying the use of fully copied paragraphs by appealing to the concept of “unacknowledged borrowings” – and telling us that they deserve to keep their A+ (actually, getting one of the few permanent research positions offered by the CNRS is equivalent to much more than an A+, it would be more like being the valedictorian at an elite university).

But I suppose that it’s normal to ask LESS of a tenured researcher, compared to a bachelor student, in terms of scientific integrity. I am sure there would be a good La Fontaine pastiche to be written here, with the title “The researcher and the student” (“Selon que vous serez puissant ou misérable, les jugements de cour vous rendront blanc ou noir”).

Really this distinction is so intellectually challenging that it makes sense that the commission who made this distinction tried to stay anonymous. On that topic, does someone at the CNRS knows if anonymity is the rule for this kind of report? I had a look at the other report posted on this section of the CNRS website, regarding cases, concerning potential scientific malpractices of biology researchers at the Institut Pasteur (https://mis.cnrs.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Rapport-CNRS-Pasteur-INSERM.pdf) and the report was signed by the commission. I don’t know who decides whether or not the commission stays anonymous in this sort of cases and I would be curious to know. It seems to me that this kind of report should be signed as a matter of rule (asking established foreign scholars to write such reports should normally be enough to avoid the potential pressure that comes with writing under your name).

2-“The sin, not the sinner”. I know this is an old line, but old lines can be quite good sometimes (see the French saying about old pots and good soups…). M.R. certainly deserves our compassion (among other things, though). But her fault remains a fault and denying it, hiding it, blurring the lines of integrity, is itself a fault. The way the report mentioned her hardships (competitive academia, pressure to publish, etc.) to exonerate her simply feels like a slap in the face. I am a young French researcher without a permanent position and I also feel pressured to publish. I also find it difficult to write in English, as we were not trained to do so when we started our studies in France, and it only became recently (more or less) required of us to pursue an academic career in France in the humanities. I think that we are dozens, even hundreds in that case: nevertheless, it simply NEVER occurred to me to start copying & pasting entire paragraphs of the work of others. It has always been obvious to me that I should not do that, at least since I started to do research (the undergrad version of me would maybe have thought about it differently). I would feel ashamed to do that, and I think that this would also be the reaction of 95% (maybe even more) of my young colleagues.

More generally, it feels like a slap in the face that this obvious case of plagiarism, widely recognized by the scientific community (11 of her articles have been retracted, from 7 different journals! – see the retraction watch article), is simply denied here through the use of moral and juridical acrobatics. It is hard not seeing it as a sign that, as an honest, hard-working, not particularly well-connected young scholar, you have little to no place in French academic philosophy, not matter how long your list of publications, how good your international reputation, how glowing the judgment of your peers. There are so few permanent jobs available that there will almost always be someone with better connections, and/or someone who has simply cheated, to beat you in the competition for jobs. And if the cheaters are finally caught, no one will say anything, an anonymous commission will exonerate them, people who find that shocking will be silenced – and everyone will carry on. I find this deeply depressing.

excellent points about the so-called report which, with its deceiving verbosity, deliberately distorsions reality and intends to deny the work (i) of many scholars who, in their capacity of experts in the board of the 7 journals, patiently analysed and eventually decided to retract not less than 11 articles, (ii) of important publishing houses who decided to interrupt their projects with MR and (iii) of the vast majority of scholars in medieval philosophy from Parisian institutions (including those who initially supported MR for the permanent position at CNRS) and around the world who officially reject MR in front of the authorities of the CNRS etc. (several letters signed by honest, non-deceiving scholars have been sent to authorities in the past months).

What MR and the so-called report did to our community of scholars is more damaging than what Martin Stone did (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_William_Francis_Stone)

MR and the so-called report must not overshadow the truly hard work of excellent anglophone and non-anglophone scholars producing original contributions.

In response, we should simply ignore MR, the report and its deceiving rapporteur. These “manipulateurs” (both young and senior) showed their measure. Enough is enough. We waisted too much time and energy with this case, while could have advanced with our work. The major lesson that I what to retain is that we need to show more support to the vast and silent majority of honest scholars of our field in particular and of the CNRS in general.

And what about the young French scholars who are horrified by what is happening to Magali Roques, and who don’t believe in academia any more for this reason? Is this the message the French community send to the world?

Can you expand on what you mean by “what is happening TO MR”? I think what a lot of people are concerned about is that nothing is in fact happening to her, despite some fairly egregious actions.

Or was your comment more directed at the general “look at the pressure that academia puts on scholars and what it drives them to do” situation?

How can you be so sure that “nothing is in fact happening to her”? Did you contact her or the persons in charge of the investigation?

Having 11 articles retracted is not something that just *happens to* one, accidentally. She could have done scholarship the way the rest of us try to do. Sara is right that the surprising fact here is what’s *not* happening.

I am not and have not been involved in the investigation; I have been in contact with Magali, whom I consider a friend. This does not mean I condone either her plagiarism or the results of the commission.

[comment deleted by request of author]

But this is something that MR did, not something that happened to her.

The only way to defend MR in this situation would have been to attack the system. We are ALL suffering under English-domination: each of my articles has been proof-read by an English native speaker, paid from my mostly miserable postdoc income. And we are ALL suffering under unrealistic publish-or-perish pressure. I perfectly understand MR from a human point of view. I however don’t have any comprehension with the commission, which defends her unfortunate personal choices. It makes me angry that copying ready-made phrases in English and publishing is apparantly less reproachable than sticking to the standarts and thus failing to publish 11 articels per year. The CNRS’ ehical commission undercuts the fairplay among postdocs. Fix the rules, please, instead of bending them to the person you support.

PS It is not only the French academia which suffers under the Omerta-silence. I have personally stayed quiet in English and in German contexts in similar cases.

From the human point of view you can understand the pressures of publishing, but they are common to all scholars. To respond to these pressures by stealing the work of others and passing if off as your own is doing ill not just to those whose work you stole but to fellow-researchers who are behaving ethically.

none of us is immune to errors, and while MR’s failing could be seen on a personal level, the decision of the commission has a rule-setting power. It *could* have been impersonal. But it is very apparantly not. In this case, the commission has acted as a mafia structured body, instilling feud and silence.

I was under the impression it was still possible to have an academic career in France (at least in the humanities) without publishing in English. I understand the need to be competitive also for other job markets, but would an American post-doc with only English pubs have a competitive advantage over a normalien(ne) with mostly French pubs for a cnrs/maitre de conf position ?

I haven’t been following the job market in France very closely in the past couple of years but I think I know of a few appointments with no English pubs (which is totally ok – there’s excellent stuff being done in French that unfortunately goes unnoticed on my side of the pond).

I am not well acquainted with the specifics of the French academia job market, but considering the usually prolongued postdoc stage (which can last from 0 to lifelong) one has to apply to variety of non-national funds and fellowships, which are more often than not announced in English, or are directly funded by EU. Publishing in prestigious journals (the majority of them in English) is another point. Then again, French market could be relatively large, but you have lots of scholars from smaller countries whose language does not count as any official language outside their country of origin (all the way from Portuguese to Polish, and Belgian to Bulgarian). Securing a next postdoc funding means stauying on the road. Like for most postdocs, MR’s CV is not France-centered, having e.g. Finland and Germany as its stops. That is why publications in English are cucial, as being internationally visible and high-profile.

I agree with ichbinhanna. I find that the situation regarding English is rather similar in France for most young scholars, although it might heavily depend on their subfield (but all subfields take the same direction). There are very few postdoc offers in France, especially in the humanities, and a shrinking number of junior permanent positions, so people who want to continue doing research after their PhD must usually go abroad to get a postdoc, which requires publishing in English (no one cares much about what you write in French in other countries: you are unlikely to land a good postdoc will only publications in French). The alternative route is to go to teach at a lycée (if you are agrégé or certifié) after your PhD, and keep on applying to jobs at the CNRS or at universities. However, teaching at a lycée is very time consuming, so you will be unlikely to manage to publish much during that time, which means that you will not be competitive in terms of publications compared to people who went abroad for postdocs. Of course, it is not a problem in 100% of cases, given that the system is partly corrupt: if you are well-connected and lucky enough, even a pathetic list of publications can get you a job. So, for some, it might be worth staying in France, teaching at a lycée, not publishing much and do a whole lot of networking…

Here is another discipline, and another country, but a very similar finding that, in spite of borrowing material without attribution, a dissertation was free of plagiarism.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-35769001

One of my Facebook friends, a prominent economist, had a great line about what’s going on here:

The more I think about the more I see the ridiculousness but have to admire the bold audacity of the play. That is, you are head of CNRS and you find out one of your permanent employees has 9 papers retracted. What do you do? If you consider the option of firing them you have lots of downsides: legal hassles, union hassles, hassles from philosophers plus that it was publications in English which were the problem and I am sure all French scholars hate that they feel they have to write in English. So that is out. But doing nothing has downsides. You cannot look weak on academic fraud. Hence their play: (a) get some dupes to create a new standard of plagiarism and admit your person was guilty of sloppy scholarship but not plagiarism, (b) then you can claim your person is the victim of being falsely accused of plagiarism so (c) she has suffered professionally enough from these false accusations so we don’t need to make that worse by also punishing her so (d) she says she is sorry about sloppy citation practices, promises not to do it again and CNRS positions itself as tough on academic fraud and plagiarism “properly so called” but also loyal to their team, who they give a second chance after their suffering as a victim of false charges. It is a narrow corridor but with enough chutzpah and willingness to bald face lie with a straight face its doable–which is all heads of organizations can ask for. No wonder though this was their first comment on this since it happened last fall…it must take awhile to find a sufficiently pliable trio to be a “commission of enquiry” to say just what you need said.

What struck me down the rathole was the “swap plagiarism” in which she took sentences from another author about another medieval philosopher Gerard of Odo and pretended it was her words about William Crathorn (including, charmingly, copying the words “in my view”). (I haven’t heard of either of these, I am just reading the report of the editors of a journal on why they retracted her work). This not only cannot be excused away as “sloppy citation” as she has to have knowingly switched the names while copying but this is worse that plagiarism, it is academic fraud at it is pretending words about one philosopher are about another. So how the apologia concludes “no fraud, no plagiarism properly so called” is beyond me.

Yes — I certainly wouldn’t want to be in the head’s place either.

But it is also noteworthy that all MR said so far was that this whole thing has been a misunderstanding. And the CNRS supports exactly that interpretation. I agree with @#inchbinhanna that this is a terrible signal to send to all the postdocs out there.

someone pointed out that she did the same with Wylton (copied ad litteram from Trifogli) and expressed her opinions on Ockham (without any change). And the rapporteur wanted to fool all of us saying that it is nothing more than loose English, negligence, lack of rigour etc. The rapporteur had the impression that he was supposed to convince fools and blinds.

Regarding Jason Brennan’s (friend’s) interpretation of this situation, it’s interesting to look at the terms of reference for the committee:

(1) ‘To distinguish between plagiarisms properly so called, on the one hand, and, on the other, what might be considered borrowings of formulations concerning matters considered to be part of the knowledge shared widely by those who are expert in the area’;

(2) ‘To give an impression of the seriousness of the faults committed by MR, quantitatively … and qualitatively’.

(3) ‘To indicate, if appropriate, supposing that the borrowings had been correctly cited, if the articles under accusation contain enough original ideas of MR’s own to justify their

publication’.

It reads to me, rightly or wrongly, as if there’s a certain steer there for how the committee was expected to approach the subject.

It is difficult to believe that CRNS had put things this way, and probably none of us would let any of our students defend themselves by reference to (1) or (3). Part of academic writing — and one of the reasons it takes so long — is that even “shared knowledge” has to be presented, and we can’t just skip writing the introduction or the background chapter altogether. One can’t just throw one’s (let’s suppose) original argument into a paper and borrow all the rest from others; the whole thing actually has to be written.

I have looked closely at some of the many passages that have been cited as instances of plagiarism, and I cannot agree with Durandus that “MR did not plagiarize ideas, but words”, or even that “she simply did not need [to plagiarize] others to write good papers”. The devil is in the details, and I suggest that anyone working in the field with a genuine interest in the truth of the matter should try working through pp. 145–149 of her article “Metaphor and mental language in late-medieval nominalism” (2019), for which seven pages of “corrigenda” are due to be published in the Bochumer Philosophisches Jahrbuch next month. If you compare the account of Ockham’s views in this part of the article to what Ockham actually wrote, you’ll find an astonishing number of serious mistakes. And if you also compare what Sonja Schierbaum wrote in Ockham’s Assumption of Mental Speech – one of the sources painstakingly identified by Pernille Harsting, from which the article only cites pp. 51–54 in one footnote – you’ll find explanations for some otherwise puzzling distortions.

By way of illustration, here are two sentences from p. 149 of the article: “Indeed, equivocation applies exclusively to spoken utterances since a sufficient condition for a term being equivocal is that it is subordinated to more than one concept. For this reason, Ockham claims, mental terms are strictly speaking neither equivocal nor univocal.” Any competent specialist will be puzzled by the first sentence, which is a non sequitur with a false conclusion. But if you look on p. 92 of Schierbaum’s book, you’ll find two faintly similar sentences that are not so puzzling (in fact, they give an accurate précis of Ockham’s view): “Equivocation applies exclusively to conventionally signifying terms, since Ockham explains equivocation in terms of what can be called a ‘multiple subordination’ involving a multitude of impositional acts. For this reason, Ockham claims mental categorematic terms like dog to be – strictly speaking – neither equivocal nor univocal.” Naturally, Schierbaum and Roques both cite the same passage from Ockham, where he says (inter alia) that “sola vox *vel aliud signum ad placitum institutum* est aequivocum vel univocum”. Now, the point about this example is that it bears the hallmark of sophisticated plagiarism: unlike the egregious cases that can be identified as blatant plagiarism even by a casual observer, here the source text has been altered so that there is less verbatim copying, but – crucially – the changes are not truth-preserving because they were not made on the basis of a genuine understanding of the source material. In this particular case, Magali has fatally excised Schierbaum’s mentions of imposition and conventional signification, leaving a nonsense that should never have got past peer review.

Obviously it would take a lot of time to examine a long string of publications at this level of detail. Equally obviously, though, this is precisely the sort of analysis that the CNRS commission should have been engaging in. That they have instead resorted to brazen casuistry is an embarrassment to the field, and I hope that those of us with scholarly integrity and a sense of shame will not be afraid to stand up and be counted.

P.S., good for you to stand up and be counted. Obviously, since this isn’t my field and since I don’t intend ever to work or get money from the CNRS, it costs me nothing to criticize Roques or them. But for insiders, taking a stance means bearing a real cost. So kudos.

Subordination to more than one concept is a sufficient condition for equivocation, but it is not necessary, since connotative terms can be equivocal even if they are not subordinated to more than one concept (since they are not subordinated to any concept) – i.e., only because whatever is expressed by the one is not expressed by the other. This is basic knowledge among Ockham scholars. An explanation in terms of imposition (i.e., why spoken words are subordinated to this or this concept) does not add anything in this context. Magali explained this to me with an infinite patience in private conversations, after I read her paper (long before it was published). I don’t see any trace of plagiarism here. Let the experts do their job.

With apologies to everyone else for the inevitable tedium, I feel obliged to explain why the anonymous reply misses my point. Firstly, Magali’s article makes the following inference: “a sufficient condition for a term being equivocal is that it is subordinated to more than one concept”, therefore “equivocation applies exclusively to spoken utterances”. If, as the anonymous reply affirms, this kind of subordination is sufficient but not necessary for equivocation, then we cannot deduce anything from it about what equivocation applies exclusively to. (This is a matter of basic logic, but if it helps to see a parallel example, try completing this inference: a sufficient condition for a creature being an animal is that it is a human, therefore animality is exclusive to ___.) Secondly, the conclusion of Magali’s inference is obviously false according to Ockham, because written terms and sentences can be equivocal as well, which is no doubt why the man himself wrote “sola vox *vel aliud signum ad placitum institutum*”. So I stand by my claim that any competent specialist will identify Magali’s inference as a non sequitur with a false conclusion.

As for plagiarism: to reiterate, the puzzle outlined above is explained when you realize (as could hardly be more obvious once the parallel has been pointed out) that Magali’s inference is an edited version of Schierbaum’s, which was itself impeccable: “Ockham explains equivocation in terms of what can be called a ‘multiple subordination’ involving a multitude of impositional acts”, therefore on Ockham’s view “[e]quivocation applies exclusively to conventionally signifying terms”. And as I say, this is merely one illustrative example. The same dishonest and unreliable modus scribendi characterizes various other passages that I have examined.

Finally, in response to the anonymous suggestion that we should simply “let the experts do their job”: if you are familiar with my expertise in the field and with John Marenbon’s, perhaps you can tell me the respect(s) in which he is an expert in this matter and I am not. I take it as obvious that there is no such thing as purely ex officio expertise.

Thank you Mark for this. I did not read MR’s papers with this level of attention and what you write is indeed an excellent refutation of my point.

In reply to Jason Brennan’s econ friend: I don’t think that MR is tenured yet.

You might have more information than I do, but I would find it surprising that someone elected “Chargé de recherches” in the summer 2019 is not yet “titulaire” (i.e. tenured, more or less) in the summer 2021. I thought it usually took about a year. I am not chargé de recherches however, so what do I know..

I’m taken aback by multiple aspects of the CNRS report, such as the contention that significant amounts of uncited and unquoted material copied verbatim from other sources can be considered as “tacit citations.” I’m also dumbstruck by their claim that it is impossible to plagiarize translations:

“…the Commission is of the opinion that three sorts of borrowings incriminated as ‘plagiarism’ by the accusers cannot be considered as such: […] (2) Published translations of medieval authors, which are thus in the public domain. Omitting the names of the translators is clearly negligent and goes against accepted standards of academic behaviour, but it cannot in any way be considered plagiarism in the sense specified above.”

Perhaps “public domain” means something different in the French context, but on an ordinary reading this appears both to be a misunderstanding of copyright law and a slap in the face to those scholars who have engaged in the difficult work of rendering technical medieval Latin philosophy into contemporary languages. At least one of the retracted papers, I recall, had multiple long translations that had been lifted verbatim from MM Adams and in each case were labeled “my translation”: if that’s not “the appropriation of the content of another’s work,” then I don’t know what could count as such — especially when publications with such “borrowings” are then used as credentials to secure a book contract with OUP for a volume of translations.

I suppose it’s easier to clear a particular author of academic misconduct if you just declare at the outset that none of what has been done by that particular author counts under your definition of misconduct.

I’m bothered by the committee’s attempt to whitewash this as mere sloppy research practices, but I’m positively angry at the harms this has done to other pre-tenure researchers, some of whom likely lost out on conference invitations, publication opportunities, research funding, and/or academic positions to someone who has made a career of such sloppiness.

I believe another point, which we, a closed academic community, tend to overlook, is what kind of image do we create to the public by decalring apparantly sloppy scholarship excusable. I believe similar cases confirm the public image of academics as useless ministerial moths who cannot produce anything worthy, but would defend each other at any cost, because that’s what people on a state job do, i.e. stick firm to their secure position. This devaluates the efforts of so many scholars working hard, and having to defend to the public eye what’s good about spending public funds on medieval philosophy. It’s like watching [French] Academia shooting itself in the foot.

From the reports produced to document the case, one particularly disturbing aspect are the instances of swap plagiarism, which have been clearly documented in the Recherches de Théologie et Philosophie médiévales 87(2) (see also Mark Thekkar’s comment). I might understand that reviewers may not recognize the plagiarized passages during the submission evaluation; but how is it possible that experts on, say, Ockham, fail to see the clear nonsense? The whole case also casts doubt on the quality of the peer review system.

To all the commentators of this post,

As a French scholar, I would like to bring here some precisions concerning this affair, which affects the French research community in a very unfair way.

First, contrary to what is written on this site, the French community has not remained silent at all. A letter signed by 50 researchers – including almost all specialists in the field – was sent to the president of the CNRS explicitly stating that the signatories no longer wished to work with this person accused of plagiarism.

Secondly, the French system has its flaws, its bureaucracy is legendarily heavy and cumbersome. But it allows people to be judged according to the law, not according to opinion or popular vindictiveness. The case was thus examined by several authorities before the president of this institution took his decision. The report that is published here does not represent the CNRS’ point of view at all. It is only a consultative opinion, written by three foreign researchers – I insist: foreign! – at the request of the CNRS Integrity Mission. The case was then examined by the National Committee for Scientific Research, a representative body with two thirds of researchers elected by their peers, which gave a negative opinion to the tenure of this person. Finally, a parity commission, with representatives of the staff and the administration, also gave a negative evaluation. Thus, contrary to what one can read on this site, where those who express themselves are totally ignorant of the French system, the case was judged according to the rules in force in France (rules of law and democratic). As a result of these statements, the president of the CNRS has just given his opinion and the person in question will no longer be part of the CNRS as of the beginning of the new academic year. Because, contrary to the myth of the French researcher’s job for life, one can be dismissed from the CNRS as soon as one commits a serious fault. The case is therefore closed.

It would therefore be useful for those who are raging here against French researchers to get some information before judging and to remember that the only positive opinion in this case comes from foreign researchers. Moreover, it is necessary to recall that all the incriminated papers were written when their author was a post-doc in various countries (Switzerland, Germany, Finland, Great Britain, etc.), never in France. Let us also recall that, with the exception of one case, all the journals that have allowed these articles to be published are not French (Belgium, Netherlands, Great Britain, Italy…). If the cleanup has to be done, it is not only in France, but almost everywhere. In any case, France has equipped itself with a system that is certainly cumbersome, but effective, and which judges, according to the standards of French law, both for the prosecution and the defence before making a decision.

Let’s hope that these clarifications will silence the uncontrolled slander of some commentators.

MR informed me – as well as many other colleagues abroad – of her current situation. She hasn’t had any right of defense nor was she informed of anything, from the first day she informed the committee for scientific integrity of the first allegation of plagiarism against her papers to the last day of her contract. Indeed, one day last week she received a letter stating that she was fired, for no reason. I don’t know whether CNRS researchers can be proud of contesting a report led according to the international criteria of scientific integrity, during more than 8 months, by means of an internal conspiracy. There is one thing I am sure of: postdocs from all over the world, don’t apply to the CNRS! I won’t. This obscure machinery is an old goat which frightens as soon as someone puts out her gun.

It is not true: MR produced a report in her defence which was consulted both by the external commission and by the members of the CNRS. Also, the direction of CNRS has consulted several commissions with CNRS members about this situation before taking a decision. The external report was clearly a failure, but it never expressed the official position of CNRS. On one thing the report and the French Scholar agree: MR did not plagiarise in her French publications. But, let us not forget, she was offered a permanent position in a French institution, where it is very hard to enter because there are very few positions, and one needs heavy support (it’s not a secret, is it?) – and that the jury and rapporteurs from CNRS were equally trumped (were they under internal pressure?), not only the people from foreign institutions.Also, I do not agree that we are dealing with “popular vindictiveness”: the expression is unfortunate. I would have used “collective astonishment”. I could not see any form of vendetta here: nobody had anything to revenge (although some may argue that she was offered a permanent position in the same year that probably another mediaevalist, honest, was not). The vast majority of us reacted when the report justifying plagiarism was made public, not when plagiarism was revealed (e.g. 46 comments on the report, 29 comments on the post about plagiarism). The fact that it took one year before she was dismissed played its part as well. I also think that the pression from scholars on dailynous had an impact. There is another thing from the French Scholars’ comment that we formed an “opinion”: well, we all read the reports from Vivarium, RPhThM and the cases presented about some of her articles: “Contingency and Causal Determinism from Scotus to Buridan” and “Metaphor and mental language in late-medieval nominalism” analysed briefly here by M. Thakkar. We all judged these evidences (not “potins”). The French community of 50 scholars signing against MR used exactly the same evidences.On dailysnous, people reacted to something that matters: the quality of the peer-review of 7 of the most prestigious journals in our field, the possibility to trump numerous funding bodies (in Germany, Switzerland etc.), the possibility to receive support from scholars and eventually receive a permanent position. The reactions here are not vindicative: those are the proof that deceiving scholars (either young, as MR, or senior, as one of the authors of the report), once revealed, won’t be tolerated by the community.”Serial plagiarism” is astonishing and rare, although it is the second case revealed in the field of medieval philosophy. CNRS and the French community had a hygienic reaction, there is no need to pretend it was much more than that and seek for glory. It is a French institution through French scholars (report and jury) on behalf of French scholars putting pressure that MR was offered a permanent position. The situation is neither better nor worse than for other institutions (including journals) and scholars that have been trumped by MR in the past 6-7 years.

MR was not fired on the ground of serial plagiarism, since otherwise a disciplinary committee would have been seized and a public statement would have been issued about the case. Only a counter-expertise appointed by the CNRS could nullify the conclusion of the first. I must confess that I don’t understand a word to what you are speaking about…

the direction of CNRS relied on various reports (as the French Scholar explained) and took the final decision after analysing all the reports (not only one).

MR was rejected by the French community and fired by the CNRS on the ground of major deontological issues detected in her work which were recognised even by one of these reports (the ‘foreign experts report’): MR “has not respected the academic standards accepted in the area” . basta.

Again, the procedure is the following: if a fault had been acknowledged by the CNRS, a disciplinary committee would have been gathered and a public statement concerning the case would have been issued. Only this committee has the right to give a sanction – which can be the termination of a work contract. MR was simply not tenured at the end of the probabtionary period. For this, no reason has to be advanced. This is the law.

I think we can all agree that there is nothing left to be said about this case. I appeal to Justin here – it would be a good idea to take down the pages concerning this story from DailyNous. Your aim was to inform the scholarly community about something serious that was happening in the field of professional philosophy. I believe this goal has been abundantly reached. Moreover, this person is no longer part of the community of professional philosophers. There is no point in keeping these pages on, provided that shaming and avenging are nobody’s goal here.

“I think we can all agree that there is nothing left to be said about this case.”

I don’t agree. This story is still developing, along at least three lines:

(1) Possible further cases of alleged plagiarism and responses to them from publishers and editors

(2) Possible official statement from CNRS on this case and/or academic responsibility

(3) This commission’s report: its intended anonymity, use of selective evidence, and bizarre reasoning raise questions about the motivation for defending MR.

I have the same definition of plagiarism as my colleagues Thomas and Sara express above which I impress on my students. I always make it very clear on my syllabus and verbally to students that ignorance of the rules is no excuse. The onus is on the writer to familiarize him/herself with the rules of citation and keep careful records of sources consulted, plus material quoted or paraphrased in an assignment. I also provide detailed written instructions on when plus how to cite and model this to students on my handouts. Hence, I always report students when I see violations, even if it could be unintentional.

However, I disagree that my practices are typical of my Philosophy colleagues and fellow academics at large. To many colleagues, it is the intent that counts and Dr David Phillips, Chair of my Department, plus Plagiarism Hearing Officer, routinely rules in favor of students when they explain how they came to unintentionally incorporate material without citation, regardless of my instructions to them.

One could argue that such lenience should not extend to someone who holds a doctorate, however, if norms of citation are not taught and reinforced consistently across a person’s educational career and if academics disagree on what actually constitutes plagiarism, then it is hardly surprising when younger scholars, like Dr Roques end up not strictly adhering to each and every norm.

For me the more important question now is not the academic question of how to define plagiarism and the degree of Dr Roques’ violations thereof, but how we, as an intellectual community should react to such cases. I do not know Dr Roques well, but she participated in a workshop in Berlin in 2015 that I was part of, and I was impressed by her contributions to the discussions. She has a lively, active philosophical mind which is not something one can simulate in the context of an in-person intellectual exchange. I was so impressed that I invited Dr Roques to be part of a panel I organized for the 2016 meeting of HOPOS in Minneapolis. I would invite her again and I was shocked that when Dr Roques recently asked to attend an online conference on Medieval Philosophy, her request was denied on the grounds that this would upset participants with a stake in the plagiarism allegations.

From what I understand, Dr Roques has apologized to each author she failed to cite, and retracted these articles. She has done the right thing by taking responsibility for her actions. It seems to me that our role as an intellectual community should be to instruct her and help her become a more careful scholar, rather than to ostracize her.

When I allege that a student has violated my university’s academic honesty policy, it is just that, an allegation. My role is then to present the evidence at a closed hearing to which the student has the right to respond. It is not my role to begin publicizing the alleged violation as though guilt were a preestablished fact, no matter how convinced I am by the evidence. I certainly cannot refuse the student entry into my classroom, or simply give them a failing grade. There is such a thing as a right to due process. Dr Roques had the right to be heard in a formal process before being convicted in advance by sensationalist online headlines. A Commission was tasked to investigate and make a determination, which it did. There is no prima facie reason to believe that each independent expert on this Commission acted from ulterior motives.

Yet, for reasons I confess I do not understand, the President of CNRS rather than following the Commission’s findings has now terminated Dr Roques, two days in advance of the deadline she was given to respond. Dr Roques has not only lost her career, but her livelihood. One part of the Medieval Philosophy community that has expressed sympathy for Dr Roques’ plight, nonetheless, is too afraid of repercussions from their colleagues to even allow Dr Roques to attend a conference in her field.

In my view, this is an abject failure on the part of the intellectual community which should be willing to instruct Dr Roques and allow her to make amends. One can fully agree that Dr Roques did not respect all the norms of proper citation and scholarship in her publications and find this deeply problematic despite the Commission’s finding that most of what she has published is original. But this is not incompatible with showing some basic human decency and recognizing that the punishments being levied against Dr Roques by the President of her institution and some of her colleagues are cruel and counterproductive. They are not worthy of us as an intellectual community. We need to do better.

“For me the more important question now is … how we, as an intellectual community should react to such cases.”

Many thanks for this nuanced comment. Seeing the discussion unfold but always harden quickly, I wholeheartedly agree that the community needs an open and constructive exchange about exactly this point.

Since we are mentioned in this post, I should probably respond (this response may not reflect the views of the other organizers). I agree with you about the general point. But for clarification, we were asked by MR to attend the conference in the very last minute (i.e., the day of), with the explicit request that she would discuss her case at the event. We, the organizers, had a long talk about the request, and it was not an easy decision to say no. But being a purely research-oriented conference, we could not have provided a forum for such a discussion, and as MR also knows, a lot of our participants (all our keynotes, and some of the organizers) are personally involved in this case, which could have lead to very unfortunate exchanges. We were not prepared to moderate such a discussion on such a short notice.

While I do not know the details of the amends MR has made with people, this case is different from many cases of student plagiarism in that it has personally hurt many of MR’s own colleagues — including the ones she “borrowed” from, but also the ones she had gained undue advantage of, in terms of publishing / academic positions. For people in less established positions, this is something difficult to swallow.

Zita, I appreciate the difficult position you and your co-organizers are in, which is why I did not name the conference in my post. I imagine that many who do not have the luxury of working in a different specialization on a different continent struggle with similar decisions. Granted, the impact of a young scholar’s actions is greater than that of a student’s, nonetheless, my general point was that in either case, all parties must respect due process. Otherwise, one risks a result driven by emotions of the cyber equivalent to a lynch mob. I echo Martin’s hope that an open and constructive exchange can occur in the future once emotions calm down. Meanwhile those concerned about the premature termination of Dr Roques’ employment at CNRS can contact Professor Calvin Normore of UCLA at [email protected].edu

I don’t see how termination of MR’s contract is premature. She has had generous amount of time to present her case to the CNRS. Respectable journals have retracted numerous of her articles. The external committee has found her guilty of serious misconduct. 50 CNRS colleagues don’t want the CNRS to allow the said conduct. Termination of MR’s contract is exactly what we should expect. Personal forgiveness and support are another issue.

If Prof. Hattab is correct in noting that “the President of CNRS … has now terminated Dr Roques, two days in advance of the deadline she was given to respond”, this this would seem to be a violation of due process, wouldn’t it?

If such a response is properly a part of the due process in place at the CNRS, then yes.

A comment above enumerates several institutional bodies that have considered the issue and claims that the case has been judged according to the rules in force in France. It is also known that MR has presented the CNRS with a number of letters of support. Also the external committee report indicates that the committee has consulted MR’s own response.

What is there to respond to at this point?

Indeed, MR presented several letters, but they should not be called “of support” – some of these letters were requested by MR at an early stage of the entire process, before the public saw the second proofs (e.g. provided by the Recherches) and before colleagues knew precisely (!) the nature of the accusations. She acted quickly and used two arguments:

(1) the argument “I have lots of support from colleagues” in order to obtain more letters (but, nota bene, many more colleagues (!) refused to write letters for her – and yes, she kept asking for similar letters even a few days before her dismissal, so basically since last year she contacted several dozen of colleagues, and all or almost all of them refused to write for her), and (2) the argument that she is persecuted (notably by the editors of the journals). With (1) she was bluffing and with (2) she was victimising. Also, some of these “letters of support” … did not support her nor justified her plagiarism.

Also, the reaction of the 50+ persons from the French (rather Parisian) milieu and the recent statement issued by the SIEPM should be considered normality (in response to Dr Hattab’s and M. Lenz’s doubts).

As for the procedure followed by the CNRS, it is very difficult to understand it from outside and through various explanations written here, but it is certain that the CNRS followed the law (the Union and other legal parts supervised the entire process etc.).

I appreciate the constructive comment that we should “reflect on how an intellectual community should react to such cases,” I think this raises an important point. However, there’s much I completely disagree with. First:

“if norms of citation are not taught and reinforced consistently across a person’s educational career and if academics disagree on what actually constitutes plagiarism, then it is hardly surprising when younger scholars, like Dr Roques end up not strictly adhering to each and every norm.”

I find this hardly an excuse for students, let alone for PostDocs, Professors, etc. I do not remember my supervisors, during my educational career, constantly reminding me that I should not plagiarize, nor is anyone sending me warning about plagiarism now that I am a PostDoc — yet I have never entertained the thought of stealing my colleagues’ work, and I bet this extends to the vast majority of my colleagues.

Also, I think the comment underestimates the scale of the problem in MR’s case; the plagiarism has been very well documented here:

https://poj.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article&id=3289003&journal_code=RTPM&download=yes&fbclid=IwAR3rQY3LO2d1obJ8WJUREC28JsRCmKFPC0VyJuf8iSWzUhAtWD-FBXdxz3E

The misconducts include cases of swap plagiarism, and “nonsense” contributions which have been retracted by respectable journals after careful examination. Also, we are not talking about a few isolated cases of plagiarism, but almost all MR’s scientific production. I am personally amazed at the CNRS’ report, not at the president’s decision to fire MR.

Second:

“I was impressed by her contributions to the discussions. She has a lively, active philosophical mind which is not something one can simulate in the context of an in-person intellectual exchange.”

Sure, and I bet she’s very smart, but I don’t fully understand the relevance of this point to the whole case. Making great contributions in convesations, panels, workshops, etc. has also a lot to do with social skills — I have also met great philosophers, with excellent publications, who didn’t make impressive comments at such academic events (because socially awkward, introvert, just tired, etc.).

(I don’t know MR personally, and I don’t have absolutely anything against her; I do hope this story reaches its conclusion with the least personal damage to her; but that’s just a completely different point).