Some Virtues Become Vices When Too Many People Possess Them (guest post)

“If individual vices can be virtuous from the perspective of a group, is the inverse also true? Does this mean that virtues, in some cases, can be vices in the context of group behavior?”

That’s the subject taken up by Mandi Astola (Delft), Steven Bland (Huron), and Mark Alfano (Macquarie) in the following guest post. The post is based on a recent article of theirs, “Mandevillian Vices“, published in Synthese.

This is the sixth in a series of guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

(Posts in this series will remain pinned to the top of the homepage for several days following initial publication.)

[a frame from Ghost in the Shell]

Some Virtues Become Vices When Too Many People Possess Them

by Mandi Astola, Steven Bland, and Mark Alfano

In Ghost in the Shell, the protagonist Major Motoko Kusanagi is asked to justify why she involves a normal human in her mission, rather than a powerful cyborg with superhuman capabilities. She replies: “If we all reacted the same way, we’d be predictable, and there’s always more than one way to view a situation. What’s true for the group is also true for the individual. It’s simple: overspecialize, and you breed in weakness. It’s slow death.” Cyborgs are stronger, more resilient, better fighters and better investigators than regular humans. However, if all the members of the crew are strong, resilient, and skilled in the same way, then the members are all similar in that way and diversity is diminished.

Many of us accept that diversity in gender, ethnicity, background and experience is generally a good thing for many groups. Many of us also accept that diversity of opinions is good. A “marketplace of ideas” is more likely to be interesting and fun, more likely to cater to the needs of different people and less likely to result in polarization and staleness, and, like Motoko Kusanaki says, vulnerability to attack and exploitation.

These types of diversity are all positive. But what about diversity in virtuousness? Might it also be better to have people with different sets of virtues and vices? And does this mean that even vicious character traits can add value to collective reasoning by increasing diversity? Are there reasons to think that we should resist trying to train everyone to a procrustean ideal of virtue, and instead embrace the benefits that vice can induce in the collectivist contexts where we spend most of our lives?

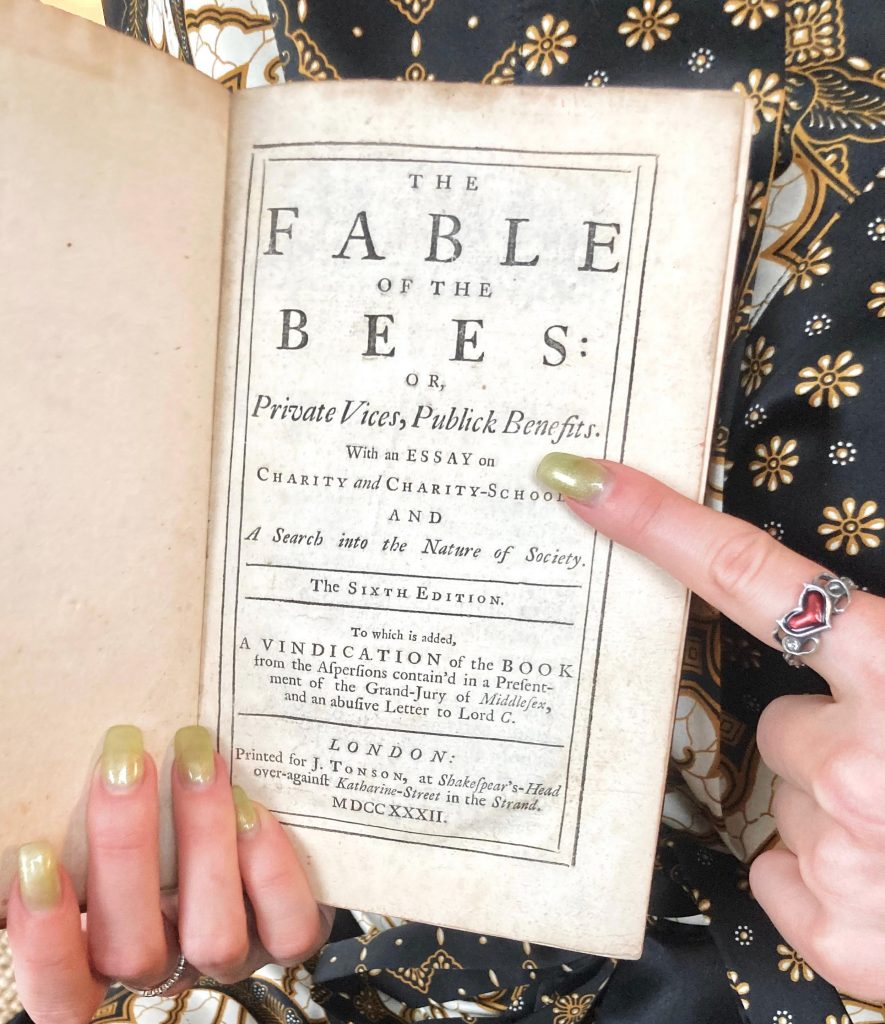

Bernard Mandeville, a Dutch economist and philosopher of the 17th and 18th centuries, wrote extensively about the public benefits of private vices. His work inspired many other important economists, such as Smith and Keynes. For example, its influence can be seen in Keynes’ paradox of thrift. If all the households live frugally and manage their finances prudently, then the economy suffers because fewer products are produced and purchased. Reckless splurging contributes to general economic welfare. Individual vices that have benefits at the level of collectives are called mandevillian virtues, and several philosophers have written about them in the context of virtue epistemology and virtue ethics (see Smart, Bland, Astola).

[An early edition of Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees, held by Mandi Astola]

When there is too much apt deference and open-mindedness…

Overspecialization breeds in weakness in the domain of thinking and reasoning. If we were all intellectually virtuous thinkers, then we would often think similarly, and miss out on the benefits of diversity.

One example of this is apt deference. Human beings are uniquely capable social learners: by relying extensively on one another, we come to know much more than we could if we relied only on our own limited devices. Social learning can increase not only the quantity of what we learn, but also the quality. We can harness the wisdom of crowds by aggregating the judgments of individuals, provided that they are independent and reliable. Francis Galton famously encountered this phenomenon at the West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition, where eight hundred fair goers wagered on the weight of a large ox. He discovered that the average guess—1,197 pounds—was only one pound short of the ox’s weight, and much closer than the vast majority of guesses. Wise individuals, it seems, defer to wise crowds.

But if everyone follows this policy, the wisdom of the crowd undermines itself. People are deferring to people who are deferring to people who are deferring, and then it’s just turtles all the way down. Even groups of reasonable conformists are liable to converge too quickly in their thinking: they forsake their collective wisdom and think like limited individuals. Consequently, groups are often well served by containing a mix of diffident conformists and independent non-conformists. The former harness the wisdom of crowds; the latter preserve it.

We see this advantageous division of cognitive labor in scientific communities. The vast majority of scientists do what Kuhn calls ‘normal science’: they solve existing puzzles within prevailing paradigms. These puzzles can be formulated only by relying on the principles and procedures that most other scientists take for granted. However, Kuhn thought that science also advances by revolutionary leaps that involve the replacement of one paradigm with another. Most attempts at scientific revolutions fail; their advocates stray too far from their discipline’s accepted wisdom. But scientific progress depends on their making the attempts. Where would biology be without the Darwinian revolution, or physics without the quantum revolution? The stubborn independence of a few scientists can also prevent theories from being prematurely rejected. The bacterial theory of peptic ulcer disease would have died decades ago were it not for a handful of advocates who refused to be swayed by, among other things, Walter Palmer’s inability to find Helicobacter pylori bacteria in his biopsies of digestive systems (he was using the wrong kind of stain to detect them).

The kinds of theoretical diversity that allow science to thrive can be maintained only if there is a critical mass of scientists ready to advocate for unpopular theories. On the flip-side, science can converge on better theories over time because most scientists are ready to defer to the judgment of their colleagues.

This kind of thing can happen when people exhibit what seems to be a virtue: avoiding myside (confirmation) bias. However, group deliberation might suffer when everyone does this. As Mercier and Sperber argue, myside bias can be epistemically beneficial in a dialogical context. When two people, both biased in opposite directions, have a discussion that’s guided by an unbiased mediator, both will need a lot more convincing, and this often means that more arguments are explored in the discussion than would be otherwise. Discussions are, after all, more interesting when people disagree a little.

There is however an amount of disagreement at which discussions become boring again, when polarization happens and interaction and exchange become difficult. This is why we stress that epistemic vices are not always good for groups, and if there is too much of them, then inquiry suffers. When that happens, the group faces a potentially irresoluble conflict in terms of attaining truth and understanding.

When there is too much mercy and forgiveness…

Imagine that a police officer stops a stressed out father who is driving his crying and fighting kids to school. Tears well up in the father’s eyes when he realizes that he has forgotten his driver’s license. The police officer might mercifully let him go with a warning, realizing that the man is on the verge of a mental breakdown. This seems like the right thing for him to do. But if everyone were always merciful in this way, then norms regarding traffic safety and rule-following would likely deteriorate. Some moral virtues also become disadvantageous when everyone possesses them. Forgiveness and mercy are among them.

Cooperation is a big part of morality, perhaps even the majority of it. And a little forgiveness and mercy can grease the wheels of cooperation because everyone makes mistakes. This is why the tit-for-tat or copycat strategy (being nice to those who are nice to us and nasty to those who have been nasty to us) is evolutionarily stable. In certain contexts, especially when miscommunication is prevalent, an even more forgiving strategy is stable: the so-called tit-for-two-tats or copykitten strategy. The basic idea is that one only defects if one’s partner has defected twice in a row. As lovely as this strategy is and as virtuous as the people who employ it might seem, if too many people adopt the copykitten strategy, the population becomes vulnerable to exploitation by aggressive defectors. Copykittens are predictable and forgiving, which can be great for cooperation, but a group of only copykittens is arguably overspecialized in forgiveness as a collective at the cost of an inability to enforce norms.

The division of moral and cognitive labor

Having everyone behave more virtuously sounds like a valuable and worthwhile aim. In many contexts, it is. But, we argue, there are also collectivist contexts where the realization of this aim would have negative unintended contexts. If everyone were virtuous, then they would think and act similarly. And dispositional monocultures are problematic when they lack the diversity required to sustain an efficient division of moral and epistemic labor.

Moral and epistemic diversity can trump individual virtue. When some moral agents are vindictive and others are forgiving, the former specialize in guarding and maintaining moral norms while the latter guard and maintain flexibility and harmony by allowing for the occasional violation and possible readjudication of those norms. Likewise, diverse collections of independent and deferential thinkers can effectively divide the cognitive labor required to harness and maintain the wisdom of crowds.

We should note that often such divisions of labor are gendered or racialized. Society expects a lot more forgiveness from women than from men, and Black people in the US, and possibly other places too, are often pressured to forgive racism. These pressures may both depend on and support social inequalities, and because they rely on evolutionarily stable strategies, such inequalities are liable to become entrenched. Whenever there is a division of labor—whether it be economic, cognitive, or moral—it is therefore important to be mindful of the position of and pressures faced by those at the bottom of the hierarchy. We want the benefits of cognitive and moral divisions of labor, but not if that depends on and perpetuates unjust or oppressive systems. This is not to insist that different populations and sub-populations have exactly the same strengths and preferences, but that whatever the distribution of strengths and preferences, proactive care needs to be taken to ensure that those with the least power are not unduly exploited. Even if some people are more disposed, by nature or nurture, to altruism and turning the other cheek, that does not mean that a just society should encourage or eagerly accept their self-sacrifice. Indeed, having a few spiteful protectors of such innocents may benefit the group.

Challenge for virtue ethics and epistemology

Mandevillian virtues and vices constitute an empirical challenge to traditional accounts of moral and intellectual virtues. It is not the first such challenge. Situationists have leveraged results from social and cognitive psychology to argue that virtues are much less prevalent than people have thought. In our new article, we use results from psychology, computer modeling, and the philosophy of science to argue that virtue theorists underappreciate the effects of personal dispositions on collective forms of thought and action. Given that most of our moral and intellectual lives are lived in collective contexts, this strikes us as a significant blind spot. Maybe it’s time for virtue theory to take a collectivist turn.

I’m not sure why “Mandevillian virtues and vices constitute an empirical challenge” rather than a normative or conceptual challenge. It is an empirical question, I suppose, whether actual communities tend to cultivate individual virtues or collective, Mandevillian ones and whether they tend to suppress individual vice or Mandevillian vice. But the more important question is which they ought to do— and what kind of individuals we should strive to be given the tension between the individual and collective standpoints.

Did Plato, Aristotle, or Aquinas believe that the virtues must be such that a society or other collective would be better off if every member of that collective fully possessed them, rather than only some members?* If not, are any major contemporary virtue theorists committed to this claim?

* at least, in Aquinas’s case, better off in this life.

Interesting piece, thanks for sharing. I am just not sure that your examples really work, however.

(1) If everyone defers all the time that creates a paradox. But always deferring is no virtue. And even if everyone defers most of the time (which may well be the case given the amount of specialization in modern societies), that doesn’t lead to a paradox.

(2) I am not a fan of the normal/extraordinary distinction in the sociology of science. For one thing, like “paradigm,” depending on what level of generality you pitch a particular claim almost anything can be normal or extraordinary science. More to the point, I don’t see why we need a mix of defending unpopular theories sometimes versus counting (the awful lot of) scientific consensus there is as truth tracking across scientists as a group. Shouldn’t each scientist exemplify the right mix on a virtue approach? You say, “There is…an amount of disagreement at which discussions become boring again,” but the ultimate aim of science is (or is compatible) with being very boring.

(3) Similarly with mercy, virtue is having the right mix. If there’s too much mercy in society (I find that hard to picture) shouldn’t virtue theorists say that too many people are being unvirtuously merciful?

I don’t see why we should treat these cases as people not being properly virtuous, rather than as something like a collective action problem. The virtue theory behind such an approach – group virtue theory? – is not, I think, widely held.