Reviving the Philosophical Dialogue with Large Language Models (guest post)

“Far from abandoning the traditional values of philosophical pedagogy, LLM dialogues promote these values better than papers ever did.”

ChatGPT and other large language models (LLMs) have philosophy professors worried about the death of the philosophy paper as a valuable form of student assessment, particularly in lower level classes. But Is there a kind of assignment that we’d recognize as a better teaching tool than papers, that these technologies make more feasible?

Yes, say Robert Smithson and Adam Zweber, who both teach philosophy at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. In the following guest post, they discuss why philosophical dialogues may be an especially valuable kind of assignment to give students, and explain how LLMs facilitate them.

[digital manipulation of “Three Women Conversing” by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner]

Reviving the Philosophical Dialogue with Large Language Models

by Robert Smithson and Adam Zweber

How will large language models (LLMs) affect philosophy pedagogy? Some instructors are enthusiastic: with LLMs, students can produce better work than they could before. Others are dismayed: if students use LLMs to produce papers, have we not lost something valuable?

This post aims to respect both such reactions. We argue that, on the one hand, LLMs raise a serious crisis for traditional philosophy paper assignments. But they also make possible a promising new assignment: “LLM dialogues”.

These dialogues look both forward and backward: they take advantage of new technology while also respecting philosophy’s dialogical roots. Far from abandoning the traditional values of philosophical pedagogy, LLM dialogues promote these values better than papers ever did.

Crisis

Here is one way in which LLMs undermine traditional paper assignments:

Crisis: With LLMs, students can produce papers with minimal cognitive effort. For example, students can simply paste prompts into chatGPT, perhaps using a program to paraphrase the output. These students receive little educational benefit.

In past courses, we tried preventing this “mindless” use of LLMs:

- We used prompts on which current LLMs fail miserably. We explained these failures to students by giving their actual prompts to chatGPT during class.

- Because LLMs often draw on external content, we sought to discourage their use through prohibiting external sources.

- We told students about the dozens of academic infractions involving LLMs that we had prosecuted.

Despite this, many students still submitted (mindless) LLM papers. In hindsight, this is unsurprising. Students get conflicting messages over appropriate AI use. Despite warnings, students may still believe that LLM papers are less risky than traditional plagiarism. And, crucially, LLM papers take even less effort than traditional plagiarism.

The above crisis is independent of two other controversies:

Controversy 1: Can LLMs help students produce better papers?

Suppose that they can. Even so, the crisis remains. This is because the main value of an undergraduate paper is not the product, but instead the opportunity to practice cognitive skills. And, by using LLMs mindlessly, many students will not get such practice.

Controversy 2: Can we reliably detect AI-generated content?

Suppose that we can. (We, the authors, were at least reliable enough to prosecute dozens of cases.) It doesn’t matter: our experience shows that, even when warned, many students will still use LLMs mindlessly.

Roots of the crisis

With LLMs, many students will not put the proper kind of effort into their papers. But then, at some level of description, a version of this problem existed even before LLMs. Consider:

- Student A feeds their prompt to an LLM.

- Student B’s paper mirrors a sample paper, substituting trivial variants of examples.

- Student C, familiar with research papers from other classes, stumbles through the exposition of a difficult online article, relying on long quotations.

- Student D merely summarizes lecture notes.

Taking the series together, the problem is not just about LLMs or even about student effort per se (C may have worked very hard indeed). The problem is that students often fail to properly appreciate the value of philosophy papers.

Students who see no value at all will be tempted to take the path of least resistance. Perhaps this now involves LLMs. But, even if not, they may still write papers like B. Other students will fail to understand why philosophy papers are valuable (see students C and D). This, we suggest, is because of two flaws with these assignments.

First, they are idiosyncratic. Not expecting to write philosophy papers again, many students will question these papers’ relevance. Furthermore, the goals of philosophy papers may conflict with years of writing habits drilled into students from other sources.

Second, with papers, there is a significant gulf between the ultimate product and the thought processes underlying it. If students could directly see the proper thought process, they would probably understand why papers are valuable. But, instead, they see a product governed by its own opaque conventions. This gulf is what enables students to submit papers with the wrong kind of effort.

For instructors, this gulf manifests as a diagnostic problem. We often wonder whether someone really understands an argument. We want to ask further questions but the paper cannot answer. In the Phaedrus, Plato himself laments this feature of writing. For Plato, written philosophy was always second best.

The Value of Dialogue

The best philosophy, thought Plato, involves active, critically-engaged dialogue. In place of the above flaws, dialogue manifests two virtues.

First, dialogue manifests the social character of philosophy. Most students are already familiar with discussing philosophical issues with friends and family. And, looking ahead, dialogue will be the main context where most students use their philosophical skills. (Imagine, years from now, a former student serving on a delicate case. She will converse with her fellow jurors, explaining subtle distinctions, asking careful questions, and identifying crucial issues.)

Second, dialogue draws us near to students’ actual thought processes. With papers, the gulf between thought process and product made it possible for someone to submit work with the wrong kind of effort. But it is difficult to imagine this in a dialogue with an experienced interlocutor.

A Promising Alternative to Paper Assignments

We all know the value of philosophical conversation. But our assessments often look different, This is because dialogues have always been difficult to administer in a fair, practical way.

But LLMs can help revive dialogue as a pedagogical instrument. We propose that, at least in intro classes, instructors shift emphasis from papers to “LLM dialogues”: philosophical conversations between the student and an LLM.

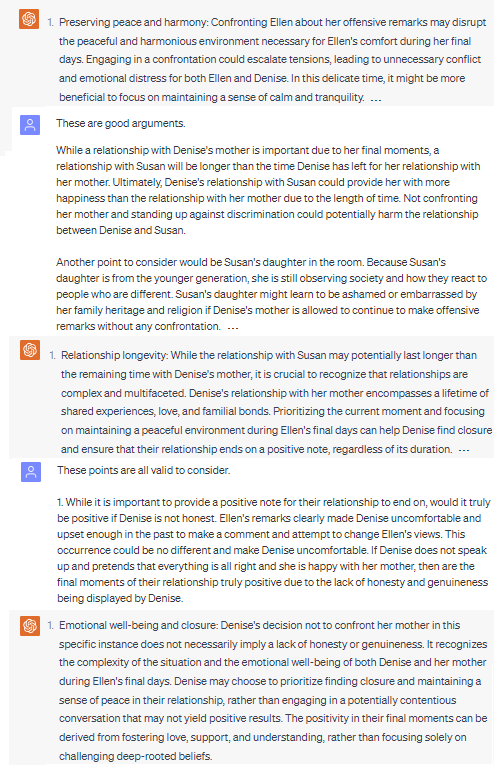

We have used many versions of this assignment in recent courses. Here is one example:

To show the assignment’s promise, here is an excerpt from a recent student’s ensuing dialogue (ChatGPT speaks first):

We offer several observations. First, the above student practiced philosophy in a serious way. In particular, they practiced the crucial skill of tracking an argument in the direction of greater depth.

Second, the transcript clearly exhibits the student’s thought process. This makes it difficult for students to (sincerely) attempt the assignment without practicing their philosophical skills.

Third, this dialogue is transparently similar to students’ ordinary conversations. Accordingly, we have not yet received dialogues that simply “miss the point” by, e.g., copying class notes, pretending to be research papers, etc. (Though, of course, we still have received poor assignments.)

Certainly, it is possible for students to submit dialogues that merely copy notes, just as this is possible for papers. But there is a difference. With papers, these students may genuinely think that they are completing the assignment well. But, with dialogues, students already know that they must address the interlocutor’s remarks and not just copy unrelated notes.

Cheating?

But can chatGPT complete the dialogue on its own? If so, LLM-dialogues do not avoid the crisis with papers.

Here, we begin with a blunt comparison. From the 500+ dialogues we graded in 2023, there were only two suspected infractions (both painfully obvious). From the 300+ papers from 2023, we successfully prosecuted dozens of infractions. There were also many cases where we suspected, but were uncertain, that students used LLMs.

What explains this? First, there are technical obstacles. Students cannot just type: “Produce a philosophical dialogue between a student and chatGPT about X”. This is because one can require a link (provided by OpenAI) that shows the student’s specific inputs.

Thus, cheating requires an incremental approach, e.g., ask chatGPT to begin a dialogue, copy this output into a new chat and ask chatGPT for a reply, copy this reply back into the original chat, etc., for every step.

But this method is difficult to use convincingly. The difficulty is not merely stylistic. There are many “moves” which come naturally to students but not to chatGPT:

- Requesting clarification of an argument

- “Calling out” an interlocutor’s misstep

- Revising arguments to address misunderstandings

- Setting up objections with a series of pointed questions

Of course, one can get chatGPT to perform these actions. But this requires philosophical work. For example, the instruction “Call out a misstep” only makes sense in appropriate contexts. But identifying such contexts itself requires philosophical effort, a fact that makes cheating unlikely. (Could LLMs be trained to make these moves? We discuss this issue here.)

There are also positive incentives for honesty. Because most students already understand why dialogues are valuable, these assignments are unlikely to seem like mere “hoops to jump through”. Indeed, many students have told us how fun these assignments are. (Fewer students have told us how much they enjoyed papers.)

A Good Tool For Teaching Philosophy

LLM dialogues help students practice many of the skills that made undergraduate papers valuable in the first place. Indeed, far from being a concession to new technological realities, LLM dialogues are a better way to teach philosophy (at least to intro students) than papers ever were.

This brief post leaves many issues unaddressed. How does one “clean up” dialogues so that they are not dominated by pages of AI text? What is the experience of grading like? If students are just completing dialogues, how will they ever learn to write?

We address these and other issues in a forthcoming paper at Teaching Philosophy. (This paper provides a concrete example of an assignment and other practical advice.) We hope at this point that philosophers will experiment with these assignments and refine them.

Despite the form, with textual input and output, it is unclear whether it’s possible to engage in a ‘dialogue’ with an LLM. It’s like asking Putnam’s ant to draw you a picture: even when its trail resembles an illustration, it can only produce the illusion thereof.

Moreover, especially for instruction on ethics or epistemology, it seems inappropriate to use tools that are themselves questionable in these respects.

Hi Sylvia,

It doesn’t matter much to us whether these exercises count as “real dialogues” or “pseudo-dialogues”: the important point is that they are useful philosophical exercises for students. We don’t think that there is anything ethically questionable about these exercises either, unless you think that using LLMs is unethical in general. We think this is a pretty benign use for the technology!

Best,

Robert and Adam

Dear Robert and Adam,

Thank you for your response. I do think that your aims are laudable and given that you are using LLMs, that this is one of the most benign applications.

As you suspected, however, I indeed think that the most well-known LLMs currently available are deeply problematic. They are developed and pushed by companies with goals very different from those of academic education or even civil society at large.

As a result, there are no publicly available data on many crucial aspects of these LLMs. See, for instance: https://opening-up-chatgpt.github.io/. It is currently also unclear how companies use the data entered by people. Moreover, jurists specialized in AI at my university are not even sure whether these tools are legal.

On the positive side, more open models are being developed and many models can be installed locally as well. I think the German academic LLM service is exemplary in this respect: https://info.gwdg.de/news/en/gwdg-llm-service-generative-ai-for-science/.

There are other aspects that worry me, including (but not limited to) the labour conditions of workers involved in the RLHF phase and the environmental impact (hard to estimate due to lack of transparency, but it’s clear that their current development and deployment are diametrically opposed to principles of frugal computing).

For all these reasons, I don’t want to recommend these tools to my students, let alone require anyone to use them.

Best wishes,

Sylvia

I might be missing something, but how do you know that the part supposedly written by the student is not written with ChatGPT? In my experience, the opening phrases (“These are good arguments”, “These points are all valid to consider”) sound exactly like how LLMs write and not how students write. Of course, if this is a dialogue that you’ve witnessed first hand, my hunch is wrong, but otherwise if someone would hand me this dialogue I would be extremely suspicious that any part in it was produced by a student.

I agree with these points, but they do address this worry in the article. There is nothing we can do that will make it impossible to cheat, all we can do is make it harder, hopefully prohibitively hard.

I don’t see how anything they suggest will make it even slightly harder.

Read the section entitled “cheating?” which is all about this. One of the conclusions being “Thus, cheating requires an incremental approach, e.g., ask chatGPT to begin a dialogue, copy this output into a new chat and ask chatGPT for a reply, copy this reply back into the original chat, etc., for every step.”

Hi Alex (and Cecelia),

Thanks for raising this issue.

1. As JDRox said, the last section discusses this issue (as does the full paper). Did you have any particular objections?

2. As JDRox also noted, we do not claim that it is *impossible* to cheat dialogues. We just claimed that it is much more difficult to cheat here than on papers.

3. You point to a simple stylistic feature that makes you suspect AI. But you can’t glean too much from these surface-level features. In the unedited dialogue, there is a lot of “stylistic evidence” going the other direction (e.g., the student’s part butchers sentences, etc.).

But here’s the crucial point: we want to avoid, as much as possible, the situation where we as instructors are squinting hard at the text, wondering if it is “real”. These surface-level stylistic features are far too noisy and far too easily faked to be reliable evidence. Furthermore, it is just brutal to approach every assignment like a private investigator.

4. Here, LLM dialogues have a fundamental advantage. The reason it is difficult for students to cheat this assignment has nothing to do with style. This is a glorious feature (as anyone who has had to prosecute dozens of LLM cheaters will agree). Why are they difficult to cheat?

The first difficulty is technical. As discussed in the post, students cannot just ask chatGPT to produce a dialogue with a simple prompt, e.g.: “Produce a philosophical dialogue between a student and chatGPT about X”. This is because the assignment requires students to provide a link to their original, unedited dialogue within the OpenAI interface itself.

Thus, as discussed in our post, cheating would require some kind of incremental approach, e.g.: ask chatGPT to begin a dialogue about topic X, copy this output into a new chat and ask chatGPT for a reply, copy this reply into the original chat and ask chatGPT for a rebuttal, etc..

But this is difficult to do convincingly. Challenge to the reader: without using your philosophical abilities, use the above method to produce something that looks like a genuine philosophical discussion between an LLM and a student. (Remember, you have to include the link to your actual dialogue within the OpenAI interface itself.)

As said above, the difficulty here is not stylistic. Instead, the difficulty is: there are dialogical “moves” that students naturally make, but chatGPT does not. We mention some of these in our post and others in the longer paper.

5. So even if a student does cheat convincingly, the cheating is not mindless. We discuss this in the post. This is why we think that most students will just find it easier to argue with chatGPT on one’s own.

Best,

Robert and Adam

If your goal is to teach students to engage in philosophical dialogue, why tell students to have “dialogue” with an automated bullshit generator? Why not ask them to engage in a real dialogue with you or with a classmate?

I do not see a move toward greater depth in the sample dialogue posted above, on either side of the conversation.

Agreed – I bet it is also less likely that two people would cheat (e.g., exclusively use Chat GPT), if forced to work together. Why not have two students write a dialogue together? Maybe even present it in class? With enough scaffolding, you can decrease the temptation to cheat because you don’t let students wait until the last minute to start (one of the main reasons people cheat…)

I can see several reasons. I can’t speak with all my students, group projects are constant headaches, the experience of speaking with a chatbot is a bit more of a controlled environment, etc. For profs who already integrate discussions in their practice, it could be a place to hone conversation skills in preparation for actual dialogues. For those who don’t, it could be less scary than opening the floor to all sorts of opinions.

Hi Rob and Chris,

In fact, we have tried these forms of “live dialogues”. They have advantages, but they also have major drawbacks (such as the ones mentioned by Louis).

Oral exams: Often, there is simply not enough time to schedule several one-on-one meetings with every student (especially for instructors who teach three of four courses with 30+ students per class). In addition, some students are confident and charismatic speakers; for others, speaking one on one with a professor is stressful. So there are concerns about fairness when grading students on these public performances.

Student-student dialogues: we have found that, without instructor guidance, these assignments tend to “go off the rails”. There are also the concerns with fairness mentioned above.

We discuss these cases in more detail in the longer paper.

–

As for ChatGPT being a “bullshit generator”: to be frank, I’m not so impressed with GPT-3.5 as a philosopher myself. (Admittedly, GPT-4 is better.) However:

1) At least for certain topics, and when using certain guidelines for prompts, ChatGPT is at least good enough to be an effective dialogue partner for an introductory student. This can be seen from the example we provided. And we have had many, many students tell us how helpful they have found these assignments.

Note: for these assignments to be effective, you definitely need to do careful testing beforehand. It certainly isn’t the case that you can give a student any topic whatsoever, without any further guidance, and get a great result. But, by this point, we have refined some assignments that we think work very well.

2) Even when ChatGPT *does* bullshit, it is STILL useful. For example, in my current class, I had my early modern students debate ChatGPT on the Cartesian Circle. ChatGPT’s understanding of “clear and distinct perception” was a total caricature. But this ended up being perfect- I could really tell how well students understood the Cartesian doctrines by seeing how well they “called out” the mistakes made by ChatGPT.

-Robert and Adam

I hear your concerns about the fairness of grading student-student dialogues and the difficulties of scheduling oral exams. The concern about shyness is a bit surprising to me. At the business school where I teach ethics, many courses require in-class presentations. Is there a reason to consider confident, charismatic speaking more of an unfair advantage than confident writing with good academic English style?

I was also surprised by your comment, “Even when ChatGPT *does* bullshit, it is STILL useful.” ChatGPT almost always bullshits! As Emily M. Bender et al. point out (“On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots”), an LLM does not have a model of the world. OpenAI openly admits that during the “reinforcement learning” used to train ChatGPT, “there’s currently no source of truth.” So ChatGPT cannot make truthful or sincere statements. It cannot lie, either, since lying requires an intent to speak falsely. It is designed to sound good. Except in a few specific contexts (e.g., when it is asked to generate fiction or wordplay), it is designed to sound good by sounding truthful despite not being truthful. That’s bullshit.

https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3442188.3445922 (Bender et al.)

https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7t4wr.2 (Harry Frankfurt, “On Bullshit”)

For a class assignment requiring LLM use to be ethical, it would be important to acknowledge that the assignment involves engaging with bullshit. That’s a potentially problematic message, pedagogically. Don’t we want to communicate to our students that philosophy isn’t bullshit?

Let me just focus on your worry about bullshit, since it gets into particularly interesting terrain.

(Robert speaking for himself:) It may be surprising that, like you, I take a rather dim view of the philosophical abilities of current LLMs (although I think that GPT4 is far superior to GPT3.5). In fact, in my own work, I identify systematic failures of deductive reasoning exhibited by LLMs. But we disagree on how this is relevant to pedagogy.

You write: “For a class assignment requiring LLM use to be ethical, it would be important to acknowledge that the assignment involves engaging with bullshit. … Don’t we want to communicate to our students that philosophy isn’t bullshit?”

But, crucially, for these assignments, I do not tell students to *emulate* the LLM. In fact, I tell students that one of their jobs is to “call out” the LLM’s argumentative mistakes. So, if anything, the message to students is: philosophy is (partly) about calling out bullshit.

From your perspective, LLM dialogues are going to be like dialogues with a terrible sophist: someone who just tries to “sound good”. But consider: many of Socrates’ own dialogues involved sophists. And when students read Plato, they don’t think that philosophy itself is bullshit, merely because it sometimes has to engage with bullshit. So, even if you are correct about LLMs, I still think these dialogues have value.

But, let me add: I would also deny that, in the use we envision, talking to LLMs is total bullshit. Sure, you may argue that this is true in a technical sense, given that they don’t have a world model. But, for students, this technical issue is irrelevant; what’s important is that LLMs do not act like total bullshitters when asked about, e.g., utilitarianism. Students can have perfectly sensible exchanges on this topic for 3-4 pages without it descending into chaos. The reader can check this for themselves.

Here, one may particularly worry about the fact that LLMs sometimes just “hallucinate” straightforward historical/empirical facts. But, if one is judicious with prompts (and tests them beforehand), this issue never comes up in practice. For example, I would not ask students to debate a purely exegetical question about Hume (or any “straightforwardly factual” issue). But, from testing, I know that it is perfectly fine to ask about objections to utilitarianism.

In reality, chatGPT’s main philosophical flaw is not hallucinated bullshit. Its flaws are much more mundane: it provides lists of arguments instead of developing one in depth, it loses track of its position, it brings up new considerations instead of responding to an objection, etc. But these are exactly the mistakes that humans make. So, in our view, it is pedagogically useful for students to learn to “call out” these mistakes.

These are interesting issues to think about, thank you.

Robert and Adam

Thank you for your thoughtful and detailed reply. It sounds as if you are trying to be up front with students about ChatGPT’s limitations. That seems to me the most important thing if you are choosing to incorporate this technology into your teaching.

The only role I see for LLMs in my teaching is a discussion of their technical limitations and the ethical problems associated with using them. “Hallucination” is not the main issue I’m worried about.

Induction from past instances is fallible. Still: it always looks like less work for us — and it always ends up being more work for us.

We nevertheless hop on the bandwagon each time, because we are caught in a game-theoretic trap: https://youtu.be/_8wLnh7gVLg?si=LrUhZvKVL26FRkHR

Hi Marc,

Just to be clear, we do not think that these assignments are a way for instructors to do less work. However, there is one nice benefit on the grading side: both Adam and I think that dialogues are more fun to grade because of more interesting variability.

-Robert

Thank you for this, Robert and Adam (and Justin for having it as a guest post here). While recognizing there may be limitations or other concerns, I think what you put together here is really interesting and creative and I can see real value in it. I downloaded your forthcoming article and look forward to more detail.

I also just want to say that while you both are very graciously engaging the comments (and adding some great insight as you do so), many of these comments read to me the very same as when I would introduce some new assignment or method in my classes, find success over multiple semesters with hundreds of students, and then I share it and immediately everyone is like “could never work. Absolute bullshit. Here are all the ways it will fail”, etc. etc. Just absolute refusal to even consider that maybe, just maybe, the folks who have actual experience with the thing maybe have a bit more insight as to its feasibility than a random keyboard warrior.

Anyway, great work you two. Thanks.