Is There A Sound Philosophical Method? (guest post)

“Is there a sound method for constructing and assessing philosophical theories—one capable of generating theories, in diverse subfields, that deliver philosophy’s ultimate goal?”

That is the question taken up in this guest post by John Bengson (University of Texas at Austin), Terence Cuneo (University of Vermont), and Russ Shafer-Landau (University of Wisconsin).

It is based on part of their book, Philosophical Methodology: From Data to Theory (2022, Oxford University Press).

* * *

[James Welling, “7690” (detail)]

Is There A Sound Philosophical Method?

by John Bengson, Terence Cuneo, and Russ Shafer-Landau

It’s a striking fact about contemporary philosophy that different subfields privilege different methods. If you ask moral philosophers for their preferred method, you’re likely to get an earful about reflective equilibrium. Metaphysicians will probably sound off about theoretical virtues or how to weigh costs and benefits. Epistemologists tend to favor the method of cases and conceptual analysis, propelled by thought experiments and counterexamples, or perhaps an ameliorative variant guided by socio-political aspirations. There are also divisions within subfields (think, for instance, of differing approaches in philosophy of mind), along with fealty to particular methods associated with specific schools or traditions: phenomenology, ideological critique, hermeneutics, deconstruction, and so on. Aiming to find unity amidst this apparent diversity, some have claimed that flying at a higher altitude reveals all of philosophy to employ “the method of argument.”

Is there a sound method for constructing and assessing philosophical theories—one capable of generating theories, in diverse subfields, that deliver philosophy’s ultimate goal? We as a community are called to face this question together.

The first step is to clarify the goal. Setting aside philosophy’s legitimate practical and aesthetic aims (fortifying one’s soul, promoting justice, appreciating beauty), philosophy in its theoretical mode has many proper alethic and epistemic goals. These include truth, justified belief, and knowledge. But in our view none of these is theoretical philosophy’s ultimate proper goal, conceived as that state in which the questions that open inquiry are fully resolved—there is no more work to be done. That point is reached only with a theory that is not just highly accurate, coherent, and reason-based, but also yields the sort of broad, systematic illumination characteristic of understanding. A sound method supplies this good.*

Familiar methods fall short. For instance, no matter their plausibility or soundness, analyses and arguments are by themselves insufficient to guarantee the sort of explanatory illumination at issue. Weighing up costs and benefits may select for a theory that entirely fails to secure one or more of the understanding-providing features, including illumination, so long as the attendant benefits (such as simplicity) are deemed sufficiently virtuous. Nor will reflective equilibrium do the trick, as it permits theorists whose judgments and principles conflict to relinquish an understanding-providing feature, such as illumination or breadth, whenever doing so will reinstate balance. Moreover, even in its “wide” form, reflective equilibrium notoriously fails to put inquirers on track to achieve even a modicum of accuracy.

In a way, none of this should come as a surprise. After all, these methods weren’t crafted with understanding in mind. It’d be rash to label them failures or declare them useless. Following them faithfully may well yield other important achievements: truth, justified belief, or even knowledge. But we’re on the hunt for a sound method. So we need to keep looking.

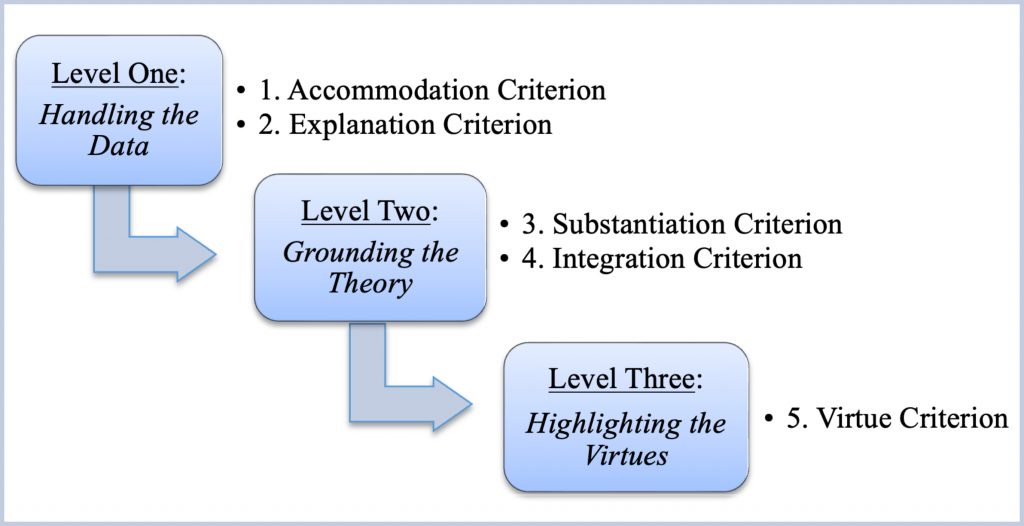

Here’s a sketch of the “Tri-Level Method” we propose in our recent book, Philosophical Methodology. As its name implies, the method incorporates a set of criteria at three levels. The first instructs theorists to handle the data associated with the topic they are inquiring about. The second tells theorists to ground all the claims they made when handling the data, as well as any further claims advanced when pursuing that grounding project. The third, enlisted only as a tie-breaker among theories that do roughly equally well at levels one and two, calls on theorists to develop their theories so as to exemplify specific theoretical virtues. The following diagram visually depicts their organization:

Let’s break this down more concretely. Our leading thought is that any sound method must take the data very seriously. There’s no theory without data. What are data? Roughly, they are inquiry-constraining starting points that serve as “common currency” for theoretical inquiry—not in the sense of being uncontroversial, but in the sense of meriting attention from theorists of all stripes. This is not a counsel of conservatism. Data are defeasible. Theorists may with perfect propriety reject one or more of them. But it is incumbent on theorists who do so to defend that rejection.**

At its first level, the Tri-Level Method consists of two criteria that instruct theorists on how to handle the data. The first criterion says that a theory must accommodate the data, rendering them likely; or it must adequately defend the claim that any such accommodation is unnecessary. The second criterion says that a theory must explain the data, saying why they hold; or it must adequately defend the claim that those data needn’t be explained.

The claims enlisted to perform these tasks are not self-standing. They must be defended, explained, and integrated in order for the theory that incorporates them to have a chance at facilitating understanding. This is the work assigned to theorists at the second level, which also comprises two criteria. The first of these calls on theorists to substantiate all of a theory’s constituent claims. In our book, substantiation amounts to defense (= offering a positive argument for) plus explanation. If a theorist declines to defend or explain a given element of her theory, she must adequately argue that such defenses or explanations are unnecessary (say, because a given claim is inexplicable). Further—and this is the second criterion at level two—all of the claims in a theory must either be integrated with both one another and our best picture of the world (which includes the deliverances of our best science), or be exempted from this stricture via a compelling argument for the acceptability of the resulting incoherence.

That’s a lot of work. If (and only if) two or more theories are roughly on par with respect to the criteria at levels one and two, theorists are instructed, at level three, to make their views as virtuous as possible—where something is a theoretical virtue just if its realization by a theory contributes to understanding. Simplicity might play this role; we ourselves are neutral. Yet the question is hardly pressing, since in practice it may be the rare occasion when a theorist has any call to advance to this third level.

It might be helpful to collect the five criteria, which amount to norms of theoretical inquiry, together in one place:

Accommodation Criterion: Accommodate the data, or adequately defend not doing so.

Explanation Criterion: Explain the data, or adequately defend not doing so.

Substantiation Criterion: Defend and explain the theory’s claims, or adequately defend not doing so.

Integration Criterion: Integrate the theory’s claims with each other and our best picture of the world, or adequately defend not doing so.

Virtue Criterion: Make the theory’s claims more theoretically virtuous than rivals, all else being equal.

Although the method does not say the criteria must be satisfied in this order, the list traces a natural progression from data to theory.

There are a few routes to defending the Tri-Level Method. One emphasizes that its criteria are constitutively connected to the understanding-providing features we encountered above. At the first level: accommodating data is keyed into accuracy; explaining them ensures illumination. By jointly doing these things with respect to a wide range of data, the theory becomes more robust, achieving breadth. At the second level: defending a theory’s claims guarantees that it is reason-based; explaining those claims extends and deepens the illumination it provides. If a theory’s claims are internally well-integrated, it will achieve coherence and, on the assumption that our best picture of the world is in decent shape, external integration offers the promise of greater accuracy. By satisfying all four of these criteria together, a theory is also poised to be orderly, hence systematic. At the third level: should two or more theories fare roughly equally well at levels one and two, we can assess their relative merits by attending to the virtues they exemplify. At this level, too, there is a constitutive link to understanding, since we defined theoretical virtues in terms of their ability to facilitate that very epistemic achievement when the first four criteria have been satisfied.

The foregoing supports viewing the method as sound. There is more to say. For instance, the Tri-Level Method is not only friendly to the various activities in which philosophers engage when they’re doing philosophy:

- advancing arguments

- raising objections

- offering replies to these objections

- providing clarification

- developing explanations (with miscellaneous virtues)

- displaying sensitivity to the deliverances of science, mathematics, and logic.

The method also explains why it is a good thing for philosophers to engage in these activities: doing so conduces to the satisfaction of the method’s criteria (which, again, are constitutively linked to philosophy’s ultimate proper goal). Moreover, it achieves this explanation while also making sense of the attractions of familiar methods. Although their directives don’t point all the way to understanding, they’re arguably attuned to one or more of the method’s five criteria.

Yet conforming to the Tri-Level Method would not be to engage in business as usual. For one thing, it calls upon each theory to handle the full range of data: no cherry-picking! It also instructs theorists to develop their views as well and fully as they can, rather than simply to exchange arguments and objections with their rivals—as sometimes happens when theorists merely shift burdens of proof, or fixate on admissible moves within a given dialectic. Further, the method advises attention to the data while discouraging undue emphasis on parsimony and other putative theoretical virtues that should play only a tie-breaking role late in the game. The method’s criteria help keep theorists’ eyes on the prize.

The Tri-Level Method is not revolutionary. Its answer to the question of method incorporates bits of wisdom from extant methods, which enjoy popularity in one or another subfield. Its elements are also familiar from the way most philosophers ply their trade. Still, the specific instructions it contains, their rationale, and the order of operations it suggests strike us as offering a promising path to attaining theoretical understanding and, consequently, to making philosophical progress.***

notes:

* This paragraph is a very brief sketch of ideas and arguments about the structure and goals of inquiry in Chapter One of our Philosophical Methodology: From Data to Theory (OUP, 2022), on which the whole of this post is based.

** We’ve noted some data about data. What theory best handles these metadata? Chapter Two critically discusses sociological, metaphysical, psychological, and linguistic theories of data. Chapter Three develops an alternative, epistemic theory of data, centering on the notion of a pretheoretical consideration that inquirers considered collectively have good epistemic reason to believe.

*** Chapter Six is dedicated to the matter of philosophical progress, elucidating the role of the Tri-Level Method therein.

What about experimental methods? Actual not thought ones. Or maybe more broadly empirical methods – It’s arguably been a part of philosophy since Aristotle and Galen not to mention the more recent movement.

Thanks, Benny! We can be pluralists here: lots of room for empirical methods in data collection, for example.

There is a lot to chew on here, but I think I am broadly sympathetic.

However, I am having trouble squaring the initial one-line rejections of others’ methods (in the fourth paragraph, starting “Familiar methods fall short”) with the conciliatory stance at the end of the piece and the ways that I can see how others’ methods could be interpreted to be compatible with this proposal. Can you help me on this front?

For instance, you write at the outset that “Weighing up costs and benefits may select for a theory that entirely fails to secure one or more of the understanding-providing features, including illumination, so long as the attendant benefits (such as simplicity) are deemed sufficiently virtuous.” But this sounds like a reason to weigh up costs and benefits in a particular way, not a reason to not weigh up costs and benefits (i.e., not a reason to doubt that the proper methodology is weighing up costs and benefits). This is an oversimplification, but you get the idea.

Thanks a lot for the piece!

Hi Graham, nice question! One core feature of CBM is its multidimensionality: it sanctions a plurality of criteria (normally, such things as explanatory power), whose satisfaction sometimes implies satisfaction of the TLM’s criteria — hence the thumbs-up toward the end. However, another core feature of CBM is its allowance of various trade-offs, which fuels the brief criticism sketched earlier: some are illicit. Might a souped-up version of CBM include additional criteria disallowing those? CBM tends to be presented schematically, making it difficult to litigate the question. We explore it in the book (ch. 4, §4), but hopefully these brief remarks offer a sense of how we’re thinking!

That’s helpful! Thanks. I will check out the book for more…

One thing that would really help me better understand your theory are examples – You say that familiar methods fall short, but I’d want to see how your method solves philosophical problems than alternative methods (e.g., wide reflective equilibrium) don’t. I guess that’s in chapter 2 of your book? (can’t quite tell what you mean by your summary…)

I agree: some examples of well-known philosophical questions or problems to which this method gets applied would be useful.

Thanks for the prompt, Chris. The last chapter (ch6) of our short book discusses problems of philosophical progress and sets out how the Tri-Level Method facilitates such progress. I wish I could give you a snappy set of examples of progress that have been achieved by using our preferred method, but since its novelty hasn’t yet allowed for proof of concept, let me offer a promissory note: our forthcoming book, The Moral Universe (OUP), puts the Tri-Level Method fully to work in the service of constructing a nonnaturalist realist account of the metaphysics and normativity of morality.

Thanks, Chris! Just adding to Russ’s reply: we illustrate the TLM with the mind-body problem at some length in ch. 5 (§4). (In fact, there are lots of examples, drawn from across the philosophical landscape, throughout.)

To be clear, the proposal is not that the method itself solves philosophical problems, as if one can simply plug in a question and the method outputs an answer. Rather, the idea is that by satisfying the method’s criteria (no mean feat!), philosophers can generate theories, in diverse subfields, that deliver philosophy’s ultimate goal.

Thank you

Thanks for the post, and look forward to reading the book! I guess the part that strikes me is this feels pretty non-naturalist and non-empirical. It doesn’t really say anywhere, for example, that we need to go out into the world and look at things, or create theories with (empirical) predictive power.

Maybe the idea is that, as John says in one comment, we can be pluralists, so maybe this is a generalized form of a more empirical approach, which can be used for both empirical and non-empirical projects.

I wonder, though, what naturalized anti-realists will make of this sort of approach, and how it’ll be useful for our thinking. We don’t need a pluralistic framework because, well, there’s only the naturalized anti-real stuff; there’s nothing else that needs accommodating. If the argument for pluralism is itself non-natural, then it won’t convince non-naturalists. So, in that sense, this account actually isn’t pluralistic, because it already has non-naturalistic commitments that naturalists would reject?

But I’ve read Russ’ other work (e.g., *Moral Realism*) and understand the basic program. Will look forward to this one and see if I can make progress on some of my above questions. Thanks again for posting!

Thanks for your comment, Fritz! Nothing in the TLM’s criteria, or our conception of data, or anything else in Philosophical Methodology favors realist over anti-realist approaches, or non-naturalist over naturalist ones. The doors are open to all!

“Philosophy’s ultimate goal.” As if the enterprise is a monolith. Whatever happened to pluralism? Oh, right — analytic philosophy did.

Hi! The post says there are many legitimate practical, aesthetic, alethic, and epistemic goals of philosophy. See paragraph 3!

The paragraph concludes: “But in our view none of these is theoretical philosophy’s ultimate proper goal, conceived as that state in which the questions that open inquiry are fully resolved—there is no more work to be done. That point is reached only with a theory that is not just highly accurate, coherent, and reason-based, but also yields the sort of broad, systematic illumination characteristic of understanding. A sound method supplies this good.”

This sort of teleological notion of intellectual history is especially poorly-suited to the history of science and the authors are hubristically attempting to find a philosophical counterpart to this imaginary, immutable, unitary scientific method. As if there were one method uniting theoretical physics, computational biology, and pharmaceutical trials, to name just three examples. It’s not just embarrassing, either. It’s harmful. Making philosophy merely and only the interpreter of scientific data leads to discrimination against world traditions which do not easily fit into the analytic paradigm and furthermore encourages the abandonment of branches of philosophy which cannot feasibly appeal to scientific data (especially ethical, social, and political philosophy, but also — albeit to a lesser degree — metaphysics).

Right, philosophy is not “merely and only the interpreter of scientific data”, and an adequate conception of philosophical methodology shouldn’t “discriminat[e] against world traditions which do not fit easily into the analytic paradigm” or “encourage the abandonment” of the various branches you list. Glad we’re agreed!

This is pretty damn interesting as well as ambitious. The one question I have–reflecting my own turn in my approach to philosophy in the last ten years–is where does pragmatism fit in, if at all? Thanks in advance for any feedback.

Thanks, Alan! Re pragmatism–our view is ecumenical about it and most other “isms,” such as naturalism, idealism, etc. The method does not itself dictate criteria for what counts as a good defense or explanation, for instance. It does not itself take a stand on what the theoretical virtues are, except to insist that their exemplification by a theory must contribute to the theory’s ability to facilitate understanding. The method is really meant to be open those of all theoretical persuasions whose aim is to provide understanding of the domain they are investigating.

Thanks so much Russ (glad you’re back with UW!). So I take it that this project is very meta. To me this suggests that your final Virtue Criterion might be the most crucial of all. In my recent work (like “Free Will Zombies” in an edited volume) I attempt to show that much work on FW results in just an argumentative metaphysical stalemate that kicks all the issues back to practical value considerations–and tries to focus on what overall values must drive our pursuits given that we have to act in rational fashion. So if metaphysical stalemates prevail, then something must take hold over them–namely, what values we can adhere to that have some commonality with all prevailing reasonable positions on FW and deliver something like reflective equilibrium that can satisfy objections well enough to quell counter objections, given the stalemate assumption (though I grant that many would not adhere to that assumption, which raises even deeper questions of why they do not). Still, this is an important exercise and thanks again.

As a non-philosopher whose academic background is mostly in the social sciences, I don’t quite get — or, perhaps, sympathize with — this effort to set out a scientific-sounding method and “ultimate goal” for a discipline, namely philosophy, that is valuable but is not a science.

P.s. That said, I recognize that philosophers often should engage with or refer to data and/or findings generated by the sciences. (I don’t think the two points are contradictory.)

I welcome any discussion of methodology in philosophy, since methods are what we sorely lack. My worries are two:

This is so vague it’s really hard to see how to apply it in any way that would settle any serious philosophical disputes.

This looks far too much like scientism, reducing philosophy to a pale imitation of the empirical sciences.

As an alternative, consider formalizing philosophical theories in recent tools like Lean or Isabelle. These tools aren’t currently ready for large-scale deployment in philosophy (they’re too unwieldy, with steep learning curves). But they can get and are getting better.

My only point is that these tools really do provide a method, that is, a standard for practice. And it’s a standard that’s not vague. (And that might help to provide philosophy students with marketable skills.). It’s a method that permits cooperation, division of labor, and progress.

It’s a plausible and interesting objection that this just reduces philosophy to mathematics. Which raises the deeper question: are there any non-reductive methods? If not, there’s probably no philosophical method at all.

This is very interesting John, Terence and Russ. I’ve got this nagging doubt, which I also had when reading the book and one that also comes up in some of the other comments. I just worry that the Tri-Level Method fails to describe a method in any recognisable sense of what methods are. I’ve been thinking of this in terms of a cake baking analogy.

Let’s say baking a cake has three stages: the mixing stage, the baking stage, and the decoration stage. It seems to me that a ‘method’ analogical ‘Tri-Level Method’ for baking a cake would be instructions for each stage that would provide desiderata of what the baker is trying to achieve at each stage: use all the required ingredients, mix them sufficiently, let the mix rest long enough, don’t burn the cake, make it beautiful, and so on.

But, if you give these for the baker, this is hopeless as a method for baking the case – we would hardly call it a method. The baker would have no idea to what actually do to bake the case. I worry that something like this is going is going on with the ‘Tri-Level Method’. We get various ideals at each stage but not steps for how to actually achieve those steps.

Because of this, for me it’s easier to think of methods of philosophy as more local argumentative structures that provide more natural steps for what to do – akin to different recipes to bake different specific cakes. In this case, there are many, many methods and they are quite specific. Some of these methods are better than others just like some recipes are better, and like it’s possible to come up with new recipes it’s possible to come up with new argumentative structures – new methods of philosophising. But, that’s just me…

Thanks, Jussi! I appreciate your concern: do the TLM’s criteria provide actionable guidance?

First pass: The TLM instructs inquirers to assemble a set of claims that accommodate and explain the full range of data, to defend, explain, and integrate those claims, and to do that as well for all other claims made in so doing. Can inquirers act on these instructions? Yes, I think so: we can do each of those things (rather than various others). Does the TLM tell inquirers how to do each of those things? No, it doesn’t: more could be said, and we’re open to exploring the options. But the fact that the TLM does not itself incorporate this further advice, or other types of advice, hardly makes it useless.

Second pass: It’s fun to think about your cake analogy! Given how we (non-trivially) explicate ‘accommodation’ and ‘explanation’ (in ch. 4, §1), the instruction to accommodate and explain the data seems far more informative/substantive than “use all the required ingredients”; similarly, given how we also (non-trivially) explicate ‘defense’ and ‘integration’ (in the same section), the instruction to defend and explain a claim, while also integrating it with all other claims and our best picture of the world, seems far more informative/substantive than “mix them sufficiently”. So I don’t think a method that incorporates the TLM’s criteria is hopeless in the sense in which the baking method that incorporates the criteria you describe is hopeless (at least for those who understand the explications; I might agree that the TLM would be rather less hopeful for those for whom the terms are empty placeholders).

One more thought: Perhaps it’d be helpful in this context also to clarify how we’re using the term ‘method.’ We’re thinking of a method of/for an activity A as a set of criteria and instructions for Aing. So a method of philosophical theorizing is a set of criteria and instructions for philosophical theorizing (= constructing and evaluating a theory that delivers philosophical inquiry’s ultimate goal). We recognize that there are also methods for other things: e.g., a method of assembling a good defense (argument), or a method of fashioning an adequate explanation, would be a set of criteria and instructions for doing those things. Of course there are also specific or “local” tests (e.g., zeugma), strategies (e.g., apply the claim to itself!), techniques (e.g., modeling), procedures (e.g., for data collection), varieties of argument, and so forth — all are helpful tools in the philosopher’s toolkit. But they’re too much for a short book like ours. While the first half of Philosophical Methodology covers the nature of inquiry and data (we think this is needed to set up a proper rendering of the question of method), its second half is focused on presenting the TLM, distinguishing it from extant methods (cost-benefit method, reflective equilibrium, etc.), showing how it handles various data about method, establishing that it’s sound, and charting its role in facilitating philosophical progress.

Dear John

thanks very much for this – this is very helpful and sensible. Just quickly – this also helps me to understand where I disagree. When you say:

“We’re thinking of a method of/for an activity A as a set of criteria and instructions for Aing”

I was thinking that methods are instructions and not criteria – that was the point of the cake example. It also seems to me, reading the book, the blogpost and your answer, that, in offering TLM, you are offering more criteria and less instructions.

When you talk about ‘accommodating and explaining all the data’, defending and explaining the claims, integrating the claims, etc. these all sound to me like criteria – what you need to end up with in order to have done a given stage well – rather than instructions for what to do in the stage and this seems to be the case even after further explication. Or at least these sound to me like very good criteria but not so good instructions. In fact, it sounds odd to me that you call these instructions even when you grant that these instructions do not tell us how to do these things – isn’t that what instructions do? And, because for me methods sound more like instructiony rather than criteria-like, I worry that no method has really been given.

A criterion is* an instruction. Take, for example, the Explanation Criterion: “Explain the data” seems like a clear case of an instruction (cp. “Take off your shoes”).

Perhaps you’re asking for instructions on how to satisfy the TLM’s instructions? My reply above was intended to speak to this: We’re open to adding such meta-instructions (e.g., concerning various styles of explanation or argument), but the TLM provides substantive actionable guidance even in their absence. Moreover, it does so in a way that, we propose, is sound (viz., it puts inquirers on track to achieve philosophy’s ultimate goal). Sorry if this doesn’t address your point/question; if so, I’d appreciate hearing what it misses.

* Remaining neutral here on how to theorize the ‘is’: is identical to, constitutes, is constituted by, is biconditionally related to, etc.

Thanks for the post, John, Terence, and Russ!

I had a response that I think is related to Eric and Jussi’s – the description of the method sounds fine, but I worry that it sounds fine because it isn’t really giving us information about how to do philosophy that everyone wouldn’t see themselves as already doing (at least at some level of abstraction). You say that the TLM is not “business as usual”, because:

“For one thing, it calls upon each theory to handle the full range of data: no cherry-picking! It also instructs theorists to develop their views as well and fully as they can, rather than simply to exchange arguments and objections with their rivals—as sometimes happens when theorists merely shift burdens of proof, or fixate on admissible moves within a given dialectic.”

Is there some philosophical methodology that endorses ‘cherry-picking’? Sure, some philosophers can be accused of cherry-picking examples, but they would presumably deny that that is what they are up to, not say ‘oh my methodology actually allows for cherry-picking’.

As for developing views as well and fully as we can and not focus on arguments and objections with rivals – Sure, this is also true, and probably something philosophers are also guilty of.

On the other hand, partly this might be an issue of how zoomed out of a perspective we take on the development of positive theories. In most debates I intervene in, I don’t think I’m in a position to offer a grand theory – I see myself as a worker bee making a small contribution to the development of a bigger theory or perspective, and providing a single argument or showing that an objection fails is my small contribution. So what looks like nitpicking can (sometimes!) be perfectly compatible with your method, and a charitable read of people in the literature is going to be that.

To rephrase, in the reflective equilibrium literature, there was a debate a couple decades ago about whether reflective equilibrium is an admissible method. Any time someone pointed out that reflective equilibrium couldn’t handle some fact or possibility, proponents of reflective equilibrium just broadened their theory, such that reflective equilibrium was conceived so widely that it was the only method anyone *was in fact applying*, whether they thought that’s what they were up to or not.

I’m a bit worried that once we interpret the methodology of almost any analytic philosopher charitably, your method will, in fact, be too general to rule anything out.

Hi Preston, thanks for your questions! I feel less confident than you that extant methods incorporate criteria that protect against cherry-picking. But let’s try to sidestep that bog. The main idea we wish to propose is that the TLM articulates a series of steps that, if taken, would result in theories that deliver philosophy’s ultimate goal. And these steps differ from various others, including those endorsed by extant methods. Inquirers following those methods have at times violated the TLM (they’re “ruled out” in your lingo). But I prefer to accentuate the positive: as you rightly observe, many philosophers are already, even if unintentionally, doing TLM-friendly work! Actually, we use just this point in ch. 6 (§2.5) to explain some of the philosophical progress that, we argue, has been made. (A further suggestion, floated briefly, is that intentionally following the TLM might just increase the rate of progress henceforth.)

Thanks for your post, Preston.It’s true that we don’t specify for how to best fulfill the constitutive criteria of our method–we do not get embroiled in the legitimate debates about what, for instance, counts as a good explanation, or what counts as, or makes, one defense better than another. One way to hear your concern, as well as those of others, is as a worry that our method isn’t specific enough because we don’t include such precise instructions. We actually think it;’s a feature, rather than a bug, that we couch things at the level of generality we do, leaving lots of room for further discussion and debate about how, for instance, to best explain or defend a given theoretical claim.

To your related worry that our method will fail to rule anything out: though the TLM does clearly borrow from extant philosophical practices, it definitely does advise against a number of common ways of doing philosophy. As one example from the field I know best (metaethics): many of those who share our moral realist sympathies regard realism as the default view, the view to beat, such that its superiority to competitors is established just so long as realists have adequate replies to objections. We strenuously disagree–it’s an important implication of our method that no theory in any philosophical field is the default one. Another example: many philosophers will start their thinking from a commitment to some form of naturalism, and argue that since a given theory is in tension with naturalism, it suffers thereby. The TLM does not license that sort of move, at least if the goal of the enterprise is to achieve understanding. Naturalism (or nonnaturalism or error theory, etc.) about some domain may emerge as a result of hewing to the instructions offered by the TLM, but are not licitly taken for granted at the outset of inquiry. Another example: many argue against a theory by claiming that it is less parsimonious (or natural or elegant or some other virtue) than a competitor. But the TLM says that this sort of comparison counts for nothing, unless the competitors are already roughly on a par with respect to their ability to handle the data and to substantiate and integrate their claims. One last example: our emphasis on handling the data at level one is quite often honored only in the breach.The TLM requires that theorists be attentive to data and construct their theories with data very much in mind. Whether you want to preserve a datum or reject it, The TLM makes it incumbent on theorists to be explicit about what the data are that bear on the questions they’re asking, and how the theory they are building handles those data. This emphasis isn’t of course unique to the TLM, but it does work at cross purposes to the way much philosophy is done nowadays.

Thank you very much for this. This is extremely interesting! I am still working my way through the positive view set out in the book, but I have two questions about how to exactly understand the reflective equilibrium method. I’m not an expert on this, so I hope I haven’t misunderstood anything.

In Chapter 4, you set out four methods of philosophical theorizing. You say: ‘Although the methods we’ll discuss are non-exclusive, each is meant to be complete, in that nothing more than following its instructions is supposed to be required in order to resolve the theoretical inquiry’ (p. 91). The four methods are the Methods of Analysis, Argumentation, Cost-Benefit Analysis, and Reflective Equilibrium.

You set out the method of reflective equilibrium as follows: When constructing a theory about a given domain, theorists ought to attend to their considered judgments that address the central questions about the domain, seeking to achieve coherence between their considered judgments (at any level of generality) and principles that account for them through a reflective process of modification, addition, and abandonment of either the judgments or principles in case of conflict (with each other, or with any of their other relevant convictions). The best theory is the one that achieves such coherence to the highest degree relative to rivals.

You say that the method has equilibrium as its sole criterion. The highest degree of coherence determines what the best theory is. I don’t have a good overview of what everyone thinks the method of reflective equilibrium exactly is, so perhaps I just have something different in mind than most. But I wonder whether we cannot understand the method of reflective equilibrium as a method of theory-construction. This is a method for building your theory/theorizing with respect to some domain(s). But this leaves it open that besides coherence there are other desiderata/criteria for adjudicating between rival theories, that is, it is not necessarily providing us with a method of theory-assessment. For example, the Cost Benefit Analysis Method you describe seems very well suited for theory-assessment (but on its own not so much for theory-construction). If two competing theories about the same domain are equally coherent, but say one lacks explanatory power or simplicity (or any of the relevant factors that come up in the CBA method), this gives us reason to favor the theory with superior explanatory power or simplicity. So, you don’t necessarily need to accept pluralism when there are two equilibria (unless both theories satisfy all criteria to the same degree). The idea being that for adjudicating between theories, theories can be equally justified in terms of coherence, but one is simply a better theory in light of other desiderata. The reflective equilibrium here would still be the source of justification, and this is what this method of theory-construction emphasizes. Or would this be a significant departure from the method of reflective equilibrium in your view? I think this would still be compatible with a ‘wide reflective equilibrium method’? Or would they want to include all this into the criterion of coherence? This might also raise the worry Preston mentions, that it makes the method so overly wide that anyone is basically applying it, and I’m not entirely sure the distinction I have in mind would help here.

And related to this, plausibly, the method of reflective equilibrium encompasses the methods of conceptual analysis and argumentation, otherwise you couldn’t (attempt to) reach an equilibrium. Of course, you say that these methods are non-exclusive, and I agree. But if the method encompasses these two methods, I wonder whether the standards/criterions of those methods (analysis and argumentation) are inherited by the reflective equilibrium method. Couldn’t we say that coherence at least to some extent presupposes that the theory provides analyses of its central terms, concepts, or properties to some sufficiently high standard, and that the theory contains conclusions of arguments whose premises and inferences meet some sufficiently high standard (p.92). If so, wouldn’t the same criteria of those methods belong to the method of reflective equilibrium as well? This would cast some doubt again that coherence is the only relevant criterion for assessment or, alternatively, that coherence as a criterion involves much more one might initially think. This might matter for some of the concerns you later raise about the method (e.g., about trade-offs and enhancing coherence at the expense of accuracy).

I’m still wrapping my head around all this, but I’d be curious to hear what you think. Thanks again for a great discussion!

Thanks, Niels. We do regard the method of reflective equilibrium as a method for theory construction (as well as providing a criterion–coherence–for evaluating a theory’s stand-alone and comparative merits). I think you’re right to be puzzled about exactly what the method is–there are different versions out there. As we indicate, we presented an austere version so as to highlight its central features, though theorists are of course free to augment or subtract various elements when devising their own preferred version of the method. As we see it, coherence is primarily a matter of consistency and explanatory relations. It’s possible that, say, analyses and arguments are brought to bear when assessing whether a theory’s constituent claims explanatorily dovetail with other claims. But the accuracy of analyses and the probity of arguments are not the same as coherence, and in many cases aren’t needed to establish coherence. We do discuss (at the end of ch. 4, section 4.3) the potential for a pluralistic method that augments reflective equilibrium with an equal emphasis on analyses and arguments. Unsurprisingly, we aren’t very sanguine about the prospects. 🙂

This is a wonderful post!

However, I am having trouble seeing how the accomodation, explanation, and substantiation criteria can be kept distinct. You say that substantiating a claim consists in giving a positive argument for it. But we often appeal to explanatory and predictive power when giving such arguments. In fact, sometimes explanatory and predictive considerations exhaust (or nearly exhaust) the positive epistemic reasons we have for believing a claim.

It is also hard to see how the substantiation and integration criteria can be kept distinct, if substantiation involves addressing objections. For many (perhaps most) objections to philosophical views take the following form: View X implies or predicts that not-p, but we know that p. So, not-X. There are two ways to handle objections of this form. One could (i) show that X does not imply or predict that not-p, or (ii) show that it needn’t bother us that X implies or predicts that not-p. These seem to correspond to (i) integrating X with p and (ii) explaining why X needn’t be integrated with p. So, in cases like these, what exactly is the difference between offering a defense and integrating a theory with the rest of what we know? (A similar question arises when a view is alleged to be inconsistent or self-defeating: what exactly is the difference between offering a defense and integrating the various parts of a theory with each other, in such cases?)

Perhaps all this shows is that there is no one-to-one correspondence between the activities that constitute theory-construction and the criteria that constitute the tri-level method: sometimes we are both accomodating data and substantiating a theory’s claims at the same time, etc. But I worry that some of the criteria are redundant in that case. In particular, I worry that substantiation adds nothing that accomodation, explanation, integration, and virtue don’t already include and that should really be thought necessary for a theory to be a good one. Perhaps offering direct sensory, introspective, or intuitive evidence for a claim is a kind of substantiation that can’t be reduced to the activities involved in meeting the other four criteria. But it is hard to see why a theory’s claims must have those kinds of evidence behind them, as opposed to other kinds of evidence, in order for the theory to be a good one.

Thanks for that, Noah. We agree that abductive defenses are sometimes good ones, and so defenses will sometimes implicate explanations. Still, it does pay to distinguish the work done by each criterion. Accommodation and explanation at level one are directed to the relevant data–these are what need handling. Various claims are enlisted to do that work. These claims, once advanced, themselves need to be ratified. How to do that? By providing arguments for them, explaining them, and showing that they cohere well with one another and with other, well-established claims outside the theory one is constructing. Each of these tasks really is a task unto itself, though we are fully on board with the idea that there can be overlap in the work done to fulfill each of the TLM’s criteria.

A smaller point, re substantiation: its most important elements are providing a positive defense of a target claim and explaining that claim. Secondary defenses–those that amount to responding to objections–are of course licit, when they abet understanding. But in our book, secondary defenses, though they occupy a great deal of space in today’s books and journals, are not the most important part of substantiating the constituent claims of a philosophical theory.

As someone coming to the end of their career, methodology in Philosophy interests me more and more. I have, in fact, become very skeptical about whether Philosophy has nearly as much to offer in terms of advancing knowledge as philosophers typically think. I think bad methodology in Philosophy is rampant. I will definitely read the book with great interest.

Thank you, Kaila–I hope the book leaves you at least a little less skeptical!

If we can’t solve the demarcation problem in science, I don’t think we can expect a single methodology in philosophy. Also, as a philosophical theory, doesn’t this have to apply to itself? It doesn’t seem that you foll your own method.

Thanks, Timothy! As it happens, we explicitly apply the method to itself (in ch. 5, §5). While the post above doesn’t emphasize this, its comment about how the TLM makes sense of various philosophical activities (in the bulleted list) is one we make in that context. We also address a few other data, before undertaking the tasks of substantiation and integration.

Regarding your other question: I don’t see how our having not solved the demarcation problem in science would be a good reason to reject the TLM.

Thanks for that. Sorry that I haven’t read the book yet.

As to how demarcation might be related to this approach…

I take it that the failure of demarcation shows there is no one, unified, distinguishing method of doing science properly. Why think there’s a method in philosophy, if not in science? Or can or does science follow your method? Have you in fact solved the demarcation problem?

Thanks for that, Timothy. I’m not sure why our inability to demarcate science from other areas of inquiry entails or even suggests that there can’t be a sound method for doing science. Assuming that there are sciences, such as physics and chemistry, that their practitioners have made lots of progress, and that such progress is not always an accident but has been achieved by following some method(s) or other, then there can be sound methods even without a satisfying answer to a demarcation problem.

Fwiw, we don’t claim that the only proper way to do philosophy is to follow the Tri-Level Method. Our claim is rather that the TLM is a sound method–successful adherence to it will yield theories that facilitate understanding. We don’t ever claim that the TLM is the only way to achieve that goal. Nor do we insist that understanding is the only proper goal of philosophizing–we allow that there are many such.

We’re unsure whether the TLM is suited to guide scientific inquiry. One reason for our uncertainty is that we haven’t thought hard enough about whether understanding is the ultimate proper goal of such inquiry. The TLM’s criteria are constitutively linked to the elements of theoretical understanding. (See the response to ajkreider below.) When scientists engage in their work in something other than the theoretical mode, or, in the theoretical mode, aim for an epistemic achievement less demanding than understanding, a method other than the TLM may be just what’s called for.

The reason that the failure to demarcate science from other areas of inquiry is a problem is that it suggests that there is no one scientific method and so science in general is not methodologically superior. I guess I misunderstood what you guys are doing. I thought the point was that Aristotle, Hegel, Marx, the Ordinary Language Philosophers, Rawls, all had methods, but yours was the best/right method. If one combines a very abstract account of what one’s method is with no particular claim about how it stacks up against other methods… Well, it’s hard to see what the payoff is. As someone asked above, are there philosophers that don’t think one should deal with all the relevant data?

Hi Timothy,

We devote half a chapter (the second half of ch4) to discussing the problems with extant methods and then a good chunk of ch.5 to describing how the TLM improves upon them. So we definitely affirm a “particular claim about how it stacks up against other methods”–we believe that the TLM is sound, whereas other methods we’ve encountered are not: the TLM’s criteria are constitutively linked to understanding, whereas other extant methods are not.

This is fascinating. Thank you for the summary, which inspires me to read the book. I’m very interested in considering whether there is a possible “neutral” standpoint from which to evaluate and compare philosophies, although I fear that such a standpoint always begins with some presuppositions, and therefore fails to be completely neutral after all.

Thanks, Zenon! If we are right, the TLM is itself a neutral basis for doing the evaluating and comparing. No matter your philosophical tastes and preconceptions, you can assess philosophical theories by reference to how well they handle the data, substantiate and integrate their claims, and, as relevant, exemplify theoretical virtues. Maybe you’re asking whether there are neutral ways to determine whether (or the extent to which) a theory satisfies the TLM’s criteria–whether, for instance, there is a neutral way to assess whether a datum has been accommodated, or a claim has been well-defended. We are cautiously optimistic about this. Though we do not ourselves drill down and advance methods or criteria for applying the TLM’s constitutive criteria–that would have made our book much longer than we wanted it to be, and embroiled us in controversies that we sought to avoid–we believe there’s reason to hope for a respectable amount of neutrality. The evidence supporting our hope are the many cases where inquirers of very different theoretical persuasions readily agree that one theory does better than another with respect to accommodating or explaining a given datum, defending or explaining a given claim, or exemplifying a theoretical virtue.

This is, no doubt, a very naive concern. But I sincerely don’t know know what:

“broad, systematic illumination characteristic of understanding”

means. I don’t know what “illumination” means here , or :”understanding”, unless they mean something like knowledge or justification. But even then, I don’t understand which is which, or what it would mean for either of those to be systematic or broad.

It’s entirely possible that the lack is in me. But elucidation would be appreciated.

Thanks, AJ. We don’t offer a full theory of understanding in the book (though John develops one in his 2017 paper, “The Unity of Understanding,” that appears in a collection by Stephen Grimm on understanding). That said, we do offer a nontrivial characterization of understanding as the sort of epistemic achievement one secures when fully grasping a theory that is accurate, reason-based, robust, illuminating (i.e., genuinely explanatory), orderly, and coherent. We say more about understanding, and why we regard it as philosophy’s ultimate proper goal, in the book’s first chapter (section 3).

Thank you for the post. This sounds like a fascinating book, and I look forward to reading it. 2 (sets of) questions (which were both partially asked prior):

I had a similar question to Timothy S. Is this an attempt to distill the *correct* philosophical method? It sounds like the answer is “no.” But, then, might it be the case that we get precisely the sort of heterogeneity in method across branches of the guild that you seem to suggest is somehow problematic? That is to say, if this is just one method among potentially very many, why should we worry about the existing methodological heterogeneity?

A second question is related to Chris’—concerning examples of the methodology’s success. I expected you to point to historical examples, but it sounds like the examples you will garner in support of your methodology will be from the purported fruits of your own application of it. Is that correct? If so, two issues came to mind. First, is it discontinuous from the history of philosophy? I suspect the answer is “no,” but it would be nice to hear more about how the methodology is presaged in particular practitioners, or particular historical instances of theory development. Who are the philosophers coming closer to getting it right, and who are those who have gotten it wrong? Second, it’s very hard to see what the “correct” view is in the present; so, insofar as you are deploying the methodology with respect to current problems, I worry that it will not be at all clear whether it has succeeded, except by the criteria you have set up. But that, of course, will not satisfy the skeptic.

Thanks again!

Thanks for your questions, Mark. In reply to the first: It’s not the heterogeneity of methods that is itself worrisome, but rather whether there is a sound method at all. A good deal of our work is aimed to showing what a sound method for doing philosophy in the theoretical mode would be. We don’t foreclose the possibility that there might be another method that facilitates understanding, but as we see things, no extant method does the trick.

As for your second question: we naturally hope that others will come to see the Tri-Level Method as a sound one and will begin to construct their own philosophical theories by applying that method. As we say, our method isn’t intended to be revolutionary, but rather incorporates, in an orderly and hopefully well-motivated way, familiar elements of how philosophy has long been done. Accommodating and explaining data, defending and explaining one’s claims, revealing how they integrate with one another and with our best picture of the world, applying theoretical virtues–each element has been present throughout philosophy’s history.

Would this method have generated any of the philosophical work the field is grounded in?

Has anyone ever done philosophy remotely this way?

Would standardizing philosophy to follow this method have generated any of the views we know and love or would it have excluded them?

If it would have excluded them, maybe we should not recommend that everyone follow this method? (Perhaps it would be nice for some to try it but as a standard method, it perhaps does not give us everything we need.)

Hi Ray,

It’s hard to predict what the outcomes of a thorough application of the TLM would be. Applying the TLM isn’t a quick and easy thing–it took us about 350 pages to do this when applying the TLM to questions about the metaphysics and normativity of morality in our forthcoming book (The Moral Universe).

To your question about whether people have done philosophy in remotely this way–well, each element of the method should be a familiar one, even if the overall method itself is novel. See my reply to Mark B, just above, for more on this.

I find this fascinating, although I wonder what continental philosophers (and those who reject the idea of robust scientific methods) would say. I do analytical philosophy in a Politics department, and I’m constantly required to specify my methods. My response is always: my method is the use of logical arguments. I draw certain conclusions from certain premises. I make sure that the arguments are consistent and valid and that the premises are justified. For the authors: what do you think a reviewer from a social sciences department would say about your proposal?

Thanks, Diego. I hope they’d say: Awesome!

We discuss the method of argument, which seems like what you are describing as your own preferred method, in our book (ch. 4, sections 3+4), along with a number of other extant methods. Constructing arguments is a vital part of doing philosophy. But it’s not the only thing, especially when it comes to constructing a theory designed to aid understanding of a target domain.

Somewhat through section 1.1 and every paragraph or so “but no data (gathering) is theory free”.

Certainly in the physical sciences It’s required that people proposing a project are clear about that and, of course, some amount of theory is required to know what is data.

The humanities Achilles heal is that people are so often clandestinely ideologically overloaded.