What the Evidence Says about whether Studying Philosophy Makes People Better Thinkers

It says: “we need more evidence.”

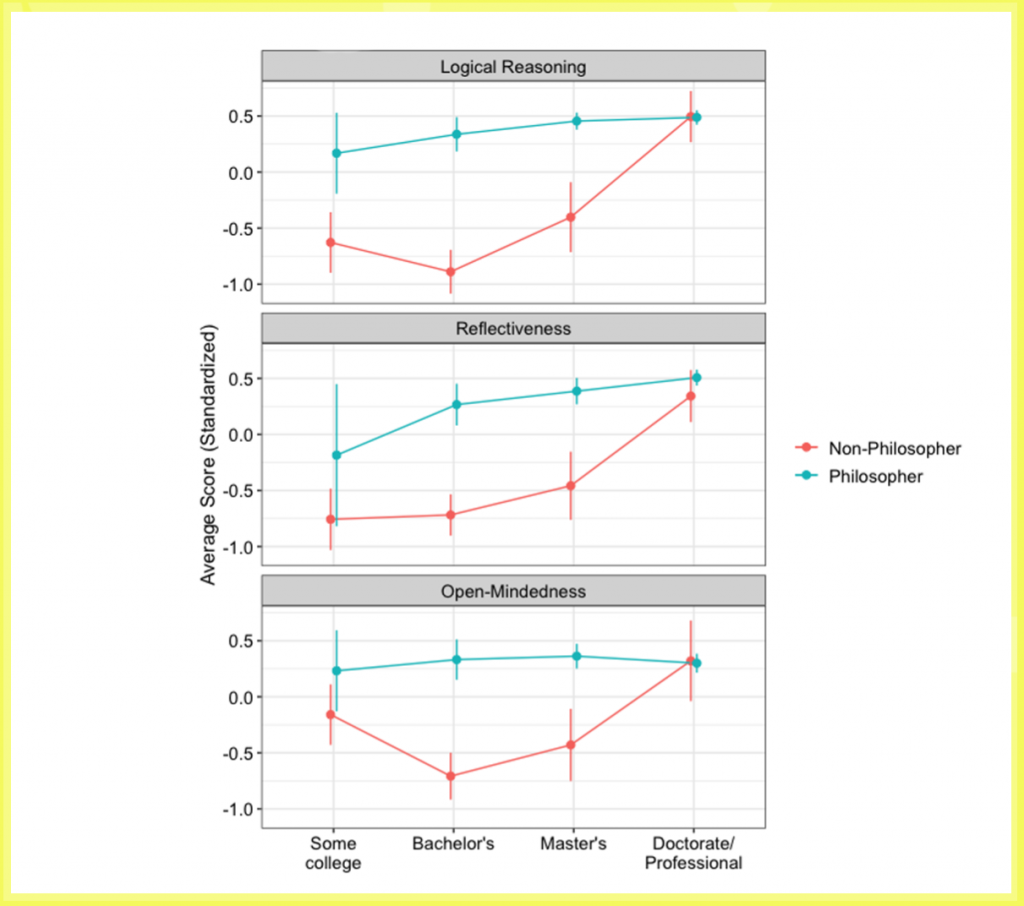

Evidence indicates that “on average philosophers are better at logical reasoning, more reflective, and more open-minded than non-philosophers.” Philosophers are more “intellectually virtuous,” as they put it (except at the highest levels of education):

Figure 1 from “Does Studying Philosophy Make People Better Thinkers?” by Michael Prinzing & Michael Vazquez. “Logical reasoning ability, reflectiveness, and open-minded thinking, grouped by philosophical training. Points indicate means and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The y-axis has been standardized for ease of comparisons across measures. Hence, 0 indicates the average; 1 indicates one standard deviation above average, etc.”

Yet the correlation between philosophical education and these intellectual virtues does not explain the matter of causation. It could be that studying philosophy leads people to be better thinkers in these ways (that is, the correlation is explained by treatment effects), or it could be that philosophical study attracts people who already have these qualities (that is, the correlation is explained by selection effects), or some combination.

To help settle the matter, Prinzing and Vazquez compared students during the first week of an introductory philosophy class with the general population of adults in the U.S. They write:

One strategy for investigating the question of treatment versus selection effects is to assess students right as they start their first philosophy course. If students at the very beginning of their philosophical education are no different from their peers, or from the population at large, then the differences we’ve observed between philosophers and non-philosophers might be due to a treatment effect. On the other hand, if those students already score substantially higher than others, then the differences we have observed are likely due primarily if not entirely to selection effects.

The data they collected suggest that self-selection may explain the prevalence of the intellectual virtue of “reflectiveness” among those who’ve studied philosophy, while studying philosophy may indeed lead students to develop or improve the intellectual virtues of “open mindedness,” being able to “see things from another’s point of view,” and being able to “imagine what an impartial third party might think about their situation.” When it comes to the quality of “intellectual humility,” the evidence was, appropriately enough, inconclusive.

Prinzing and Vazquez also looked at findings from a study on how students’ thinking changes during an ethics course, comparing the ethics students with psychology students at the beginning and end of a semester. They write:

The results indicated that the philosophy students changed their views on [ethical questions covered in the course], and more so than the psychology students. Additionally, the researchers found that the philosophy students, but not the psychology students, showed a reduced tendency to base their ethical views on intuition and emotion versus deliberation and analysis. Among philosophy students specifically, the degree to which students reduced their reliance on intuition and emotion predicted the degree to which they changed their ethical beliefs. This is an exciting set of results, both because it suggests that philosophy courses influence the way that people think about real-world issues, and also because it suggests that the mechanism behind these changes is a trait that we know philosophers display to a remarkably high degree (i.e., a tendency to engage in reasoning and reflection).

Furthermore,

The philosophy students… became more inclined to think that it is morally wrong to: “trust your intuitions without rationally examining them,” hold “on to beliefs when there is substantial evidence against them,” or “rely on anything else other than logic and evidence when deciding what is true” (these are quotes from the survey questions). This is evidence of a treatment effect.

They add: “Whether it is a desirable treatment effect, on the other hand, is less clear.”

The authors also include in the paper some thoughtful remarks about the extent to which philosophical skills may (or may not) transfer to other domains.

In the end, though, the results are inconclusive:

The full paper is here.

Related: “Philosophy Majors & High Standardized Test Scores: Not Just Correlation” by Thomas Metcalf (Spring Hill), which Prinzing and Vazquez critically discuss in their paper.

Great use of existing data and existing student populations!

1. For what it’s worth, we found that having students and crowd workers from multiple platforms think through philosophical thought experiments before completing reflection tests slightly improved test performance (compared to taking the reflection test first, d ≈ 0.3, p = 0.003). However, that effect emerged only after rejected a bunch of junk data (almost entirely from Amazon Mechanical Turk) and I don’t recall pre-registering that finding. I’ll be curious to see if others can find this seeming philosophical reflection effect.

2. Given how many students most of us have access to, Prinzing’s And Vasquez’s proposed research seems thoroughly feasible. I’ve started doing waitlist control trials between duplicate sections of courses (to test different claims), but I have yet to convince a Registrar to let me randomly assign students to each section. 😉

This is interesting. I’d like to see the results after facilitating collective reflection, via a moderated conversation, before the test is administered. Depending on the facilitation, a number of results seem plausible to me, but I have no real sense of what would likely be found.

Great work, people! I know Jonathan Surovell has looked into this research, too; my understanding is that argument diagramming is one of the few interventions with notable data supporting the hypothesis that philosophical thinking improves learning indices.

Hi Preston. I doubt we’re alone, but we have been doing experiments comparing (a) interactive reflection to individual reflection and (b) mapped arguments to standard prose.

I’ll be sure to share what we post/publish on social media; Google Scholar will probably notify our followers within a week of our posting it.

Thanks for pointing me to Surovell’s book and website!

Doesn’t have to be either/or. It could be a mixture of both. I was always analytical before I took philosophy but my thinking was still somewhat sloppy. Philosophy made me think more clearly and organized. At least analytic philosophy.

If we value making students better thinkers, it seems we should make it an explicit learning objective in our courses and programs and pursue it directly. For example, we can explicitly identify and directly reinforce philosophical reasoning skills and methods (e.g., abduction, partners in guilt, possible worlds) by using supplementary texts such as The Philosopher’s Toolkit, The Ethics Toolkit, and Philosophical Devices (links below). I presume this is more effective—or at least, more efficient—than relying on students’ indirectly picking up such methods and skills through experience. (Explicitness and directness also have equity benefits.) Additionally, our intro logic courses can emphasize teaching statistical reasoning, how to avoid cognitive biases, and other ways of being better thinkers, and de-emphasize teaching students how to solve formal logic proofs. (Personally, I like the text, Reason Better, discussed here: https://dailynous.com/2019/05/01/new-kind-critical-thinking-text-guest-post-david-manley/).

Philosopher’s Toolkit:

https://www.wiley.com/en-us/The+Philosopher%27s+Toolkit%3A+A+Compendium+of+Philosophical+Concepts+and+Methods%2C+3rd+Edition-p-9781119103233

Ethics Toolkit:

https://www.wiley.com/en-us/The+Ethics+Toolkit%3A+A+Compendium+of+Ethical+Concepts+and+Methods%2C+2nd+Edition-p-9781119891994

Philosophical Devices:

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/philosophical-devices-9780199651733?cc=us&lang=en&