New Data on the Employment of Philosophy PhDs (guest post)

As noted in yesterday’s post, Academic Philosophy & Data Analysis (APDA) has completed its data gathering for nearly 150 philosophy PhD programs, with a new data dashboard capturing nearly 6,000 philosophy PhD graduates between 2013 and 2023.

In this guest post, APDA project director Carolyn Dicey Jennings (UC Merced) discusses some of the data they’ve collected on the employment of graduates of these programs.

(A version of this post previously appeared here.)

New Data on the Employment of Philosophy PhDs

by Carolyn Dicey Jennings

Graduates of the nearly 150 philosophy PhD programs we surveyed are largely in academic jobs: 40% have had permanent academic employment (2,379 of 5,998), whereas 39% have had only temporary academic employment (2,324 of 5,998).

A much smaller proportion, 12%, has had employment outside of academia, with another 10% of unknown status or unemployed.

The proportion of graduates in permanent academic jobs varies by graduation year, partly due to the fact that it takes multiple years for many graduates to find a permanent academic job, and partly due to changes in job availability and/or reporting. For example: 55% of 2013 graduates have had a permanent academic job, which is only true of an average 30% of graduates between 2019 and 2023 (from 37% in 2019 to 26% in 2023).

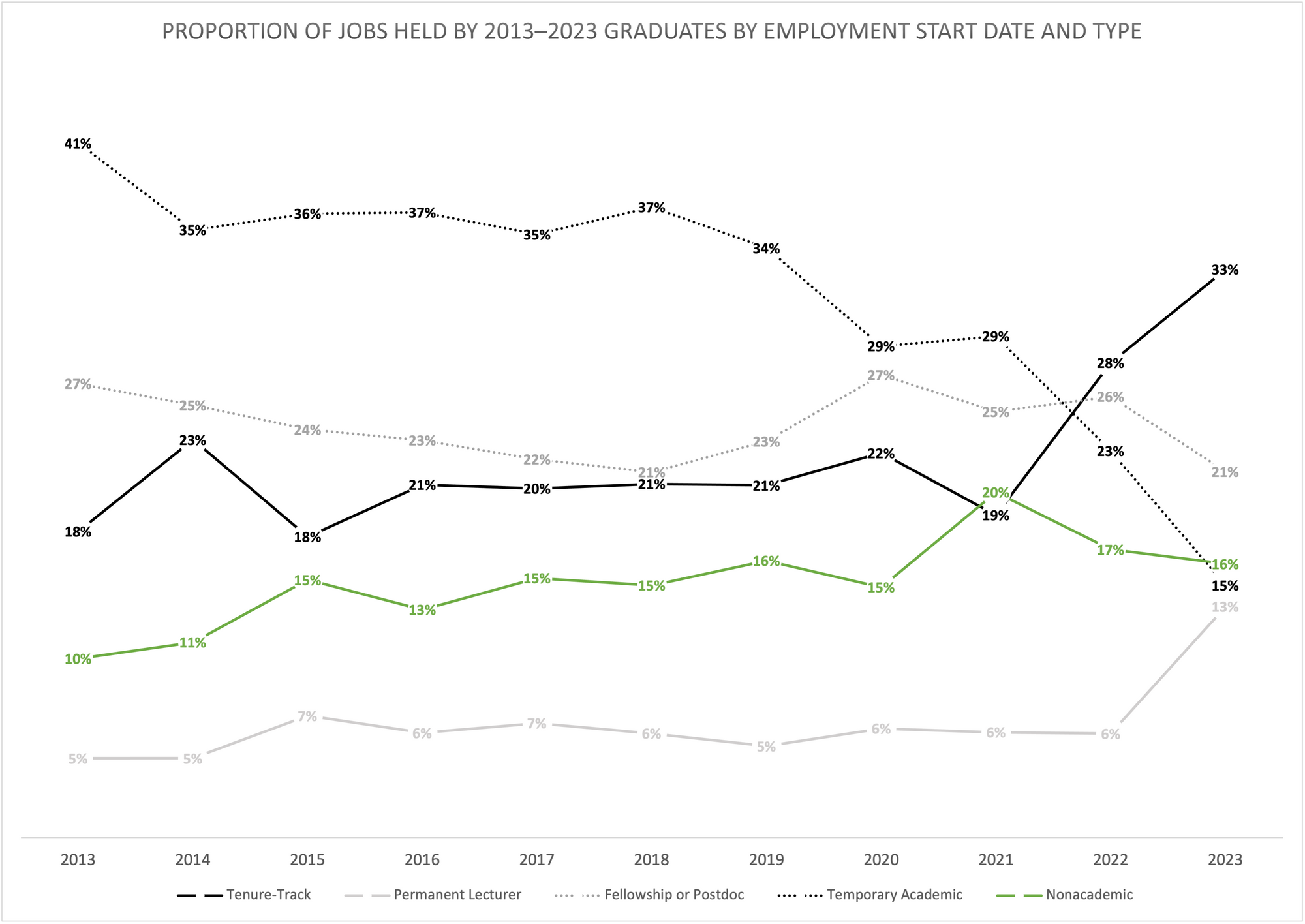

The proportion of different types of jobs held by graduates has also changed over time, with a higher proportion of permanent academic jobs for the last couple of years, likely due to reporting differences (i.e. graduates and programs are more likely to report these jobs on their websites). Setting aside the last couple of years, the proportion of tenure-track jobs and permanent lectureships has stayed largely flat (around 20% and 6%, respectively), while that of temporary academic jobs has gone down (from 41% to 29%) and that of nonacademic jobs has gone up (from 10% to 20%).

This may reflect greater interest in nonacademic jobs, perhaps due to efforts by the APA and other groups to increase familiarity with these career paths (see our post on Philosophy Works). Past research reports by APDA have found that pay is substantially higher for those in nonacademic jobs than those in permanent academic jobs, and this holds true for this year’s survey as well, with those in nonacademic jobs making an average $111,564, those in permanent academic jobs making an average $81,507, and those in temporary academic jobs making an average $51,314; this is about a $30,000 salary difference between each job type.

Outside of salary, those in nonacademic jobs are also more likely to report being able to access $1,000 or its equivalent for emergency purposes, with only 1% saying “no” in comparison to 5% in permanent academic jobs, 13% in temporary academic jobs, and 24% of current PhD students. (This is better than what is reported elsewhere for Americans overall; 57% say they cannot afford such an expense.)

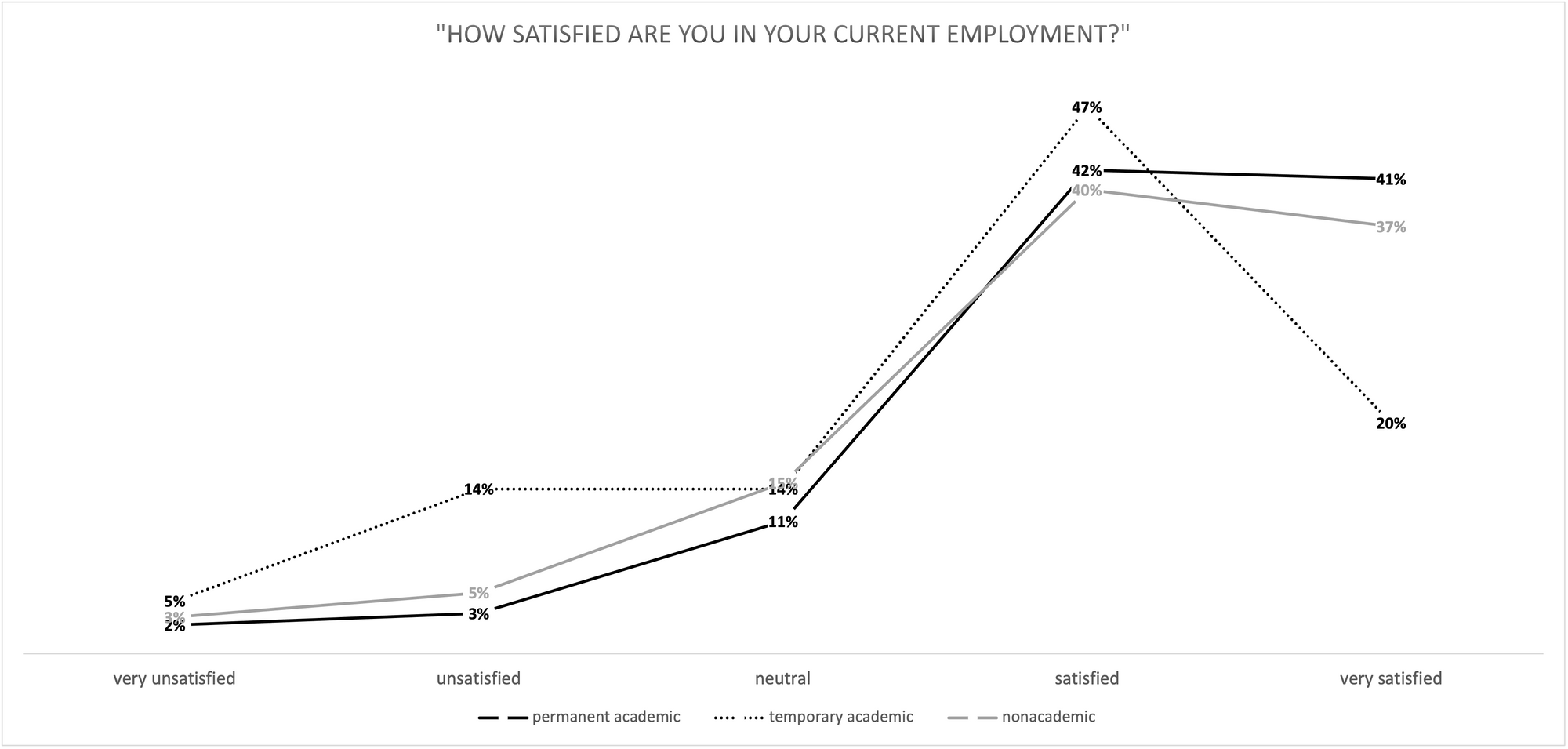

Moreover, this year’s survey found that job satisfaction is equivalent for nonacademic and permanent academic jobs. The job satisfaction for temporary academic jobs is, on the other hand, lower than these two categories.

The nonacademic sectors with higher average satisfaction than for permanent academic jobs were:

- technology (e.g. software developer)

- law (e.g. attorney)

- consultancy (e.g. consulting for a private firm)

- nonprofit/NGO (e.g. charitable organization, think tank)

More information about these and other career paths was compiled by Alex Dayer for Philosophy Works for those who are interested.

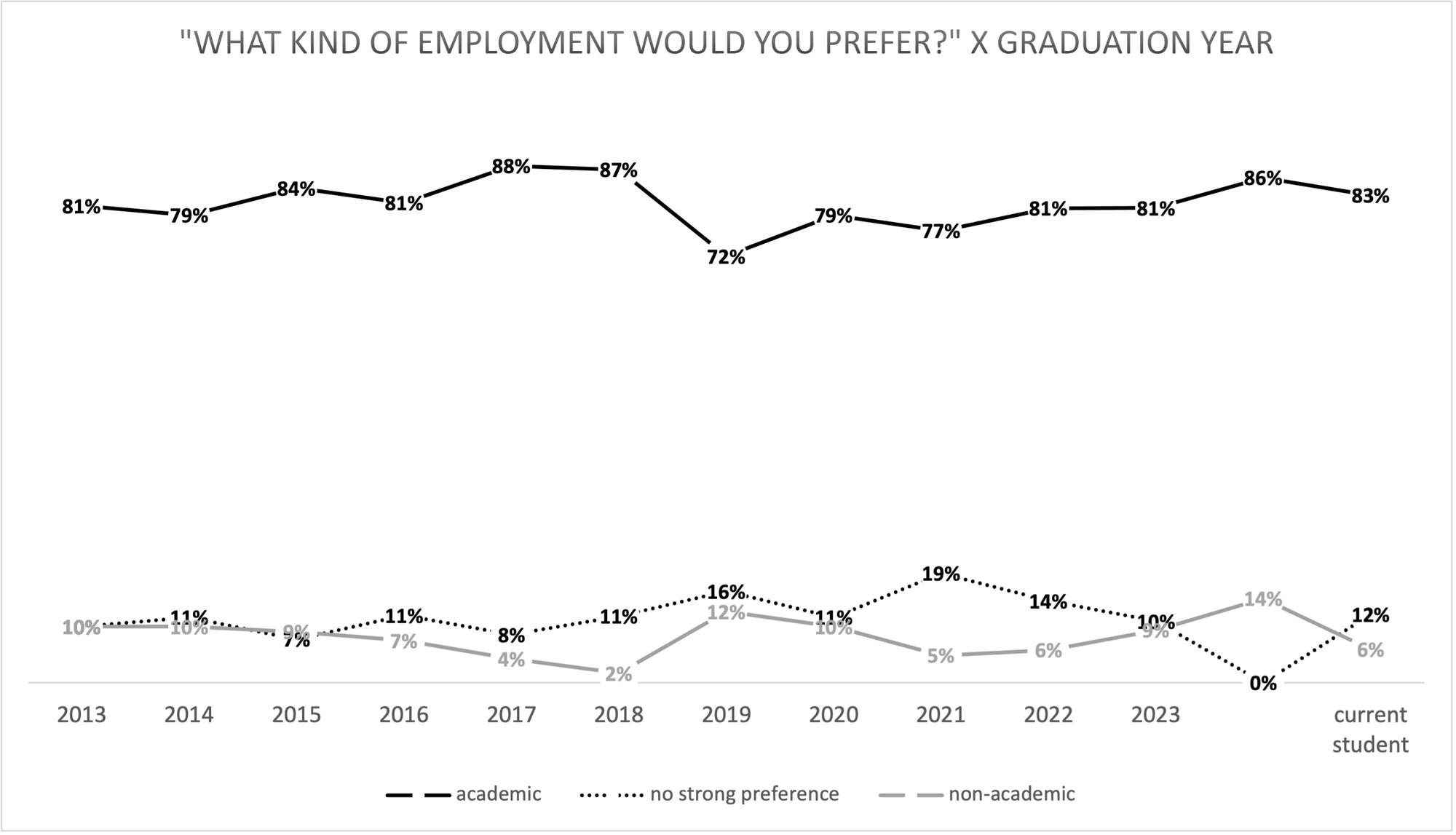

The salary and satisfaction findings are striking given the strong preference of most graduate students for academic jobs (82% of survey participants), with little change over time according to this year’s survey, and the proportion that are currently in temporary academic jobs (39% of graduates in tracked programs, and 26% of survey participants).

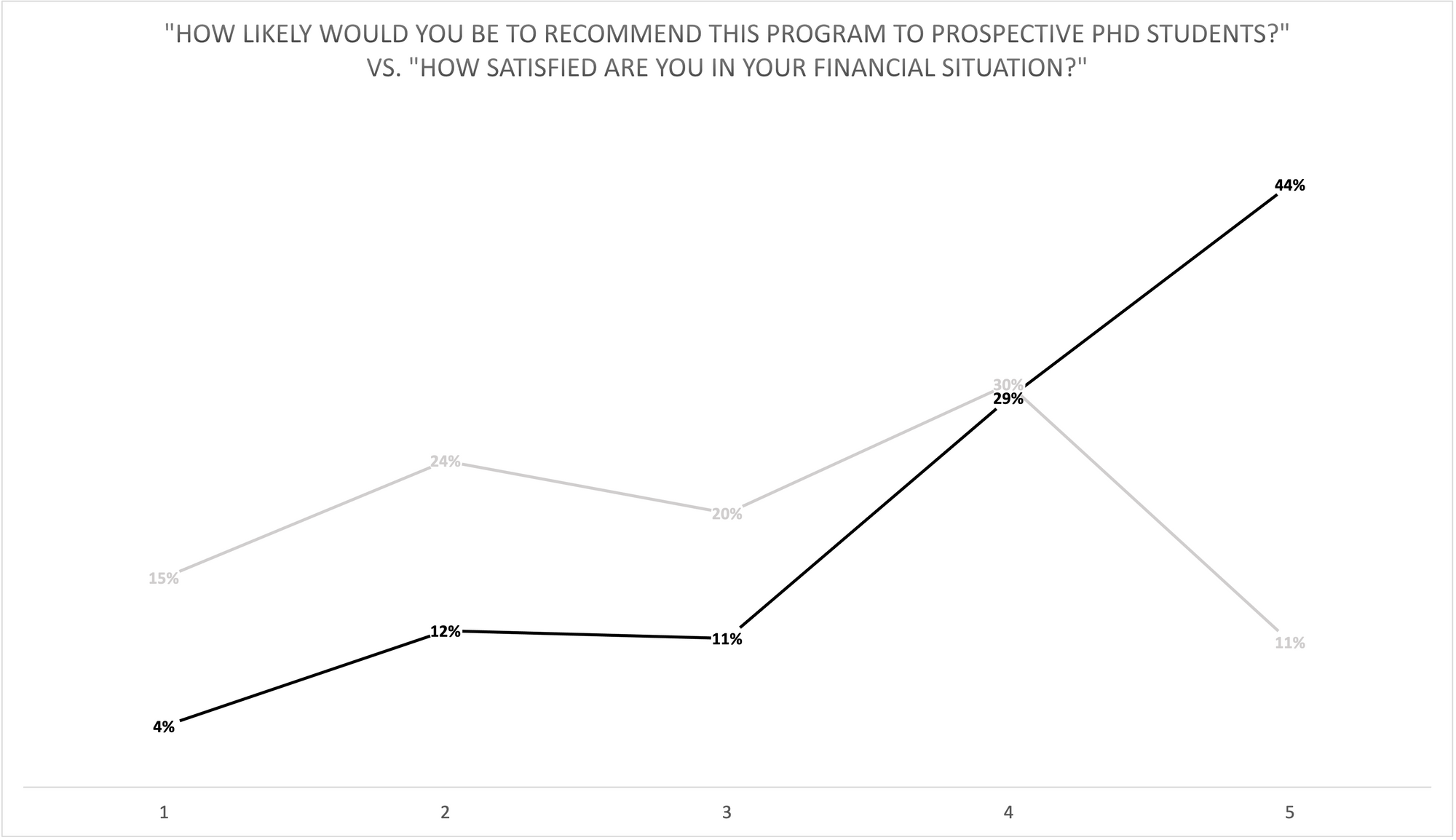

This preference for academic life is also visible in another set of questions: the plurality of current students would definitely recommend their PhD program to prospective students (black line) despite being only so-so on their financial satisfaction (gray line).

Thus, a final frontier to employment satisfaction may be finding better ways to include those in nonacademic employment in academic life. When asked about this in Q&A after a talk, Karen Kelsky of The Professor Is In recommended that programs include nonacademic speakers in their colloquia. I am currently in discussions with others in the UC system to create a network of UC philosophy PhD graduates in nonacademic careers who might be interested in such opportunities. What other ideas do people have about this? What could philosophy do to better connect philosophy graduates with satisfactory employment?

Other findings from this survey will be distributed through a research report in the coming months, in collaboration with UC Merced political science PhD student Neelum Maqsood. I may also report some of those other findings through blog posts. Stay tuned!

Every graduate department should maintain a formal network of alumni working in a variety of non-academic fields. Network members should be tapped regularly for 1:1 mentorships and panel discussions.

Networks like this should be easy to manage and cheap to run. Most ex-academics will share their guidance for free.

Faculty members cannot and need not develop expertise in the non-academic job market. They just need to connect their students with alumni, and they need to accept the fact that their students will spend some of their time cross-training—ideally under the guidance of a mentor.

(Background: I transitioned to ed tech directly out of grad school. I now work in health care as a data analyst.)

I’ve had a number of Zoom meetings with undergraduates from the University of Wisconsin (where I did my PhD in philosophy) arranged through their “success works” program that connects alumni with graduating/recently graduated students. On a couple of occasions I’ve also had philosophers I know bring me to campus to discuss my non-academic career (in my case, publishing). I’ve also been on panels about publishing at APA meetings. I’m always happy to do these things, and would encourage universities, departments, and the APA to offer these opportunities, since my impression is that they’ve been helpful for many of those participating.