Some Remarks on Form in Philosophy (guest post)

“When my younger self complained angrily in the margins with scrawls of ‘where is this going?’, he missed the sights and insights that the journey itself provided.”

A kind of philosophical innocence is the subject of the following guest post by Bradford Skow, Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Professor Skow works mainly in metaphysics, philosophy of science, and aesthetics, and has a blog/newsletter, Mostly Aesthetics, on Substack, which I highly recommend.

This is the fourth in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

[Posts in the summer guest series will remain pinned to the top of the page for the week in which they’re published.]

Some Remarks on Form in Philosophy

by Bradford Skow

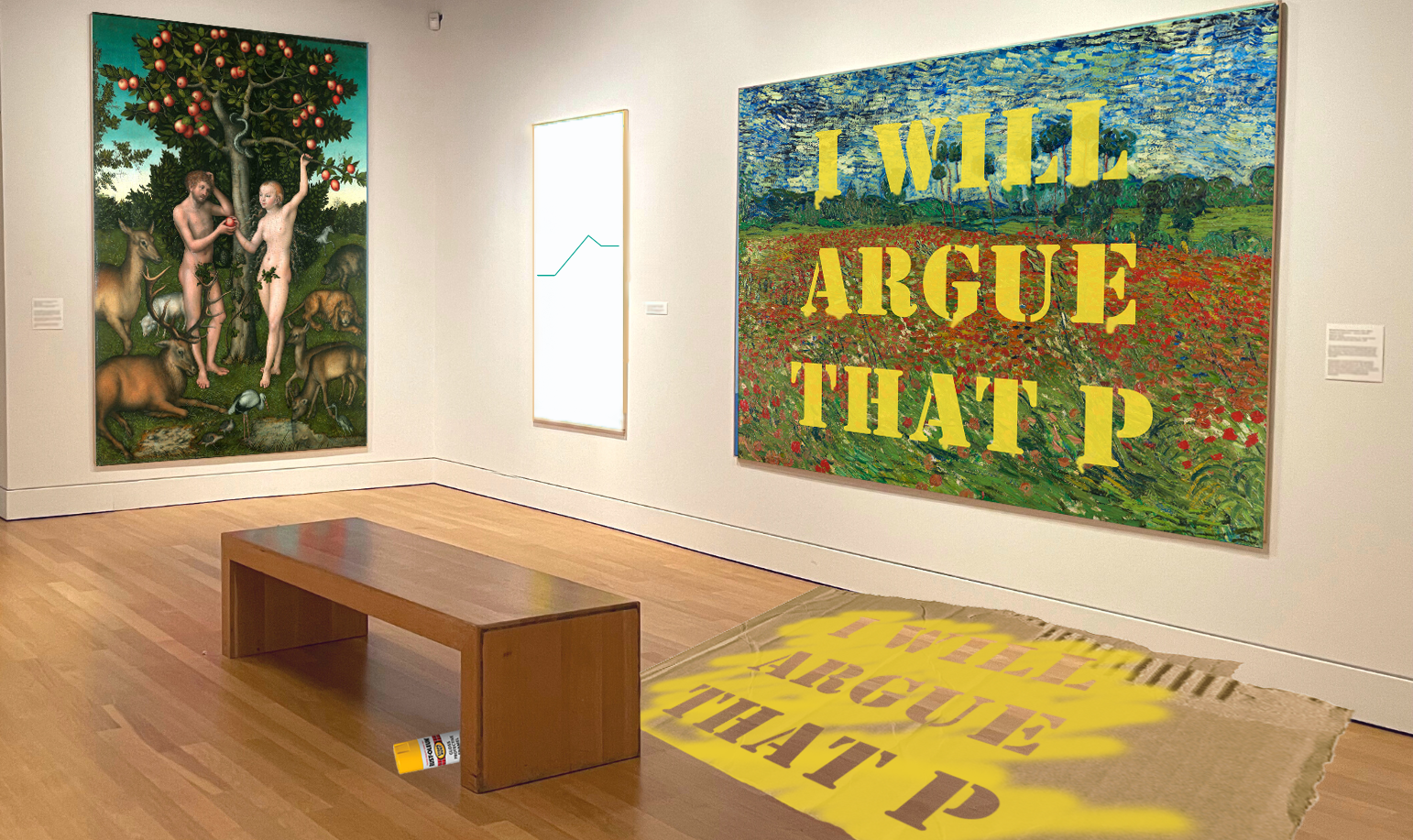

Herbert Morris read an essay titled “Lost Innocence” at the 1975 Oberlin Philosophy Colloquium. In it, he attempted an analysis of Adam and Eve’s loss of innocence, when Eve was tempted and they ate from the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The knowledge they acquired was not, obviously, perceptual knowledge, nor did they draw some new conclusion from their evidence. It is closer to say, Morris thought, that they acquired “a different way of feeling about what had been before them all along”: “[w]hereas one had earlier felt at ease, felt a kind of natural joy, one now is cursed with an absence of joy, perhaps more, with feeling anxious and bad.” But this itself is just a first approximation, and Morris steers us toward, and then away from, several more accounts of lost innocence, until, after a pause at his preferred one, he closes with a meditation on the nature of evil, and on the morally wise people who have “not been crushed by what they have confronted, but have emerged, in ways mysterious to behold, victorious, capable, despite and because of knowledge, of affirming rather than denying life.” Life-affirmation is not an ending that the essay’s opening paragraphs point you toward. Morris announces only that the essay was stimulated by reflection on the story of Adam and Eve, and he acknowledges early on the “serpentine nature” of his reasoning.

Every age has its favored philosophical templates. Readers of this venue are doubtless familiar, either as writers, or as readers or referees, with one in common use today:

I will argue that P.

Lo, notice that I am now arguing that P.

Reminder that Modus Ponens is valid!

In conclusion, I have argued that P.

On top of all this meta-signposting, not to be neglected is the obligatory here is the plan for this paper, placed at the end of the Introduction, and skipped over by every reader. The basic unit of philosophy is taken to be the argument with numbered premises and labeled conclusion, as the proof is the basic unit of mathematics. Of course books and papers in mathematics also have definitions and explanatory insertions, nor do works of philosophy consist only of arguments—not even Spinoza’s Ethics—but everything is built around them.

At sea between college and graduate school, I pursued a self-directed course of philosophical study, and focus on the argument was the straw keeping me afloat. When chance scudded me into Peter Unger’s paper “The Problem of the Many,” therefore, it seemed scandalous. “Although,” he wrote, “I think arguments are important in philosophy, my arguments here will be only the more assertive way for me to introduce the new problem, not the only way.” What an idea, that a philosophical goal could be achieved by other means.

I am just old enough to have had passed down to me, like myths of a lost age, other templates that were once more common. After his death, various collections of Wittgenstein’s notes and lectures were published, under titles like Remarks on Suchity-Such. A tradition began in which the basic unit of philosophy was—at least in presentation—the remark, sequences of which were presented in numbered paragraphs. On the surface this practice was more collegial and less aggressive, gentlemen (remember this was decades ago) lounging in tweed coats and exchanging thoughts between puffs of their pipes, but of course in reality a seemingly-anodyne “I would like to make a few remarks” was usually a preface to something devastating, or anyway intended to be so.

Because philosophy is so old, and because the ideas of the earliest philosophers are still alive today, it can seem that finding new philosophical positions, or new arguments for existing ones, requires a gold-medal performance, while those practicing other, newer disciplines languorously pick low-hanging fruit on their lunch breaks. I sometimes joke that, because of this, a career-making philosophical achievement can now consist in something as small as drawing a distinction. Or even in erasing one: I was once present when a famous philosopher complained, to the students in his graduate seminar, that one of his undergraduates could not grasp the distinction between numerical and qualitative identity, and I complained back that that student might just be a philosophical genius, seeing clearly that the alleged distinction Mr. Famous was trying to draw was not real. When Amos Tversky was a student, he chose psychology over philosophy in part because there were far fewer giants over whose shoulders one needed to see. However their eventual publications compare to Tversky’s Nobel-worthy life’s-work, I tell philosophy graduate students, they should take heart in the fact that he was a coward who could not muster the courage they have displayed.

Premise, premise, conclusion is the Freytag’s triangle of philosophy, and its de-throning in literary criticism may inspire. Jane Alison, in her book Meander, Spiral, Explode, explores a bunch of alternatives to the exposition, climax, resolution form, including the titular ones, which also makes good philosophical models. If Morris’s essay is a controlled and steady navigation by an experienced hand through a carefully surveyed territory, Arthur Danto is a great meanderer. In just the first few pages of The Transfiguration of the Commonplace he riffs on Euripidean and anti-Euripidean art, the imitation theory, and Sartre, and when my younger self complained angrily in the margins with scrawls of “where is this going?”, he missed the sights and insights that the journey itself provided.

The point is not, or not just, to have more fun, or to unleash unruly intellectual impulses that academic disciplines try to discipline. Form can be expressive in ways that matter aesthetically and even philosophically. Wittgenstein’s Tractatus sometimes achieves an austere oracular beauty that the philosophy-as-lab-report genre cannot equal and to which it cannot aspire. It is also, to some, offputtingly arrogant. To their temperament the Philosophical Investigations may be more congenial. “Bear in mind,” Kripke observed in Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language,

that Philosophical Investigations is not a systematic philosophical work where conclusions, once definitively established, need not be reargued. Rather, the Investigations is written as a perpetual dialectic, where persisting worries, expressed by the voice of an imaginary interlocutor, are never definitively silenced… the same ground is covered repeatedly, from the point of view of various special cases and from different angles, with the hope that the entire process will help the reader see the problems rightly.

If for Herbert Morris the loss of moral innocence was “like the loss of peace of mind accounted for by acquiring anxiety,” the form of the Investigations—as it struck Kripke anyway, as it presented itself to him—is expressive of a loss of philosophical innocence, and the—possibly appropriate—gnawing philosophical anxiety and uncertainty that some of us cannot shake, but may hope not to be crushed by.

I love how this comes shortly after Mark Wilson’s imitation of rigor.

To be honest, I don’t know whether you love this because Mark Wilson’s post needed more signposting and clarity (which it did!), or because you see Wilson as complaining about the same kind of thing as Skow,.

Well, it is (by design) an inkblot, so see what you wish. Here is my own take:

https://philpapers.org/rec/CHAAPC-3

Fantastic essay Marc. This quote in particular encapsulates much of the humour of the analytic/continental divide in a way I hadn’t fully realised before

To go back to one of the points made in Skow’s piece, one artefact (feature?) I’ve noticed in the form of much continental work is the willingness to engage with wordplay, ranging from unapologetic construction of German portmanteaus (as you describe in your piece regarding dasein) to philological & etymological examination of Greek/Latin roots as the starting point of analysis.

I wonder, though, why this is such a source of disapproval from the analytic camp, since playing around with words as the unit of analysis (in the broad sense) has been endemic to philosophy since at least Aristotle.

My partly tongue-in-cheek suggestion is that the example analysis you gave of “juxtaposition-ism”, whilst intended as a critical example, might yet be a valid instance of philosophical inquiry. Is there really a problem with doing philosophy by taking a word and throwing -ism at the end? Maybe there’s a path along which we accept both the continental literary slipperiness and analytic compositional verbiage as both fruitful forms of philosophy, just in different ways?

“On top of all this meta-signposting, not to be neglected is the obligatory here is the plan for this paper, placed at the end of the Introduction, and skipped over by every reader.”

I never skip these. I cherish them as a guide to which upcoming sections I can safely skip. (When appropriate, I also write them with that function in mind.)

These “table of contents” sections are also incredibly useful as someone who has read the paper several times, and is dipping back in to look at one part of what goes on, and needs to know which section to look at! They are easy (and reasonable) to skip on a first read, if you already know that you plan to read the whole thing. But they are indispensable on later visits to the paper.

Well my complaint about the “plan for this paper” stuff may not have been entirely serious.

You might have added extreme literalism as another symptom of philosophical innocence…

(Loved the piece!)

I do not think my comment implies that I took the claim to be that literally every reader skips plans. I liked the piece too.

“Skipped over by every reader.”

“I never skip these.”

I was mostly just teasing (as in: one could, ironically, read this as another example of what the piece is criticizing). But the juxtaposition of these two quotes does make me wonder…

Hi I got Dog-Whistled to Comment on THIS.

I think what you’re talking about is Narratives and Digression in relation to the composition of Philosophical Discourse, and so in essence it’s kind of a Narratological Standpoint that is being asserted here. I personally find that ALL TEXTS are Expressions of a Philosophy whether Explicitly so or through the Implicature of the Topics and their Argumentative Structure, or through something more Subtle such as Narrative Design.

As a person who is Critical of Freytag’s Triangle as it has been more or less Normalized as a Readymade Structure of Narrative Argumentation, I also take the position that Meandering can be a BAD THING.

Also, quick note, I have to Write Like THIS in order to Establish Consistency, I’m involved in a Criminal Case involving Domestic Terrorism and Seditious Conspiracy, even thought I’ve contacted the FBI and they Track my Online Activity, it just Helps Establish a Breadcrumb Trail. YES this is Real, it’s weird, and I’ve been Living with IT for OVER Half a Decade.

Anyway, back to what we might as well call the Philosophy of Narrative Composition we have to Understand something that, per THIS Investigation, I’ve come to Refer to as ‘Deep Implicature’, which is more or less the Esoterica of Philosophical Texts, because if you have a Framework as Based upon Neo-Gricean Pragmatics and van Eemeren’s Pragma-Dialectics, that can Discern Esoterica towards not just Cohesive Ties but also a Consistency towards the Intended, and often Hidden Application of a Philosophical Discourse.

When speaking of Narrative Applications of Philosophy, this used to be called the ‘Dialectic’ and we often Mistake this as the Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis Schema from Fichte has been Popularized in several Books on Writing, it’s actually slightly closer to Hegel’s original Dialectic of Abstract-Negative-Concrete, but if you really want to be Accurate goes back to Aristotle and the Organon, as a System, and I have a Rough Outline of WHAT I THINK is the Dialectic from Poetics, which I then used to ‘Read’ what some Scholars like Richard Janko believe to be a Reconstuction of Aristotle’s Poetics II, or the Discourse on Comedy.

BUT Important to ANY Constraints on Composition is the Ethics of Composition, and for that we can look to more Contemporary Developments in Narratology, notably James Phelan. In the Introduction to his Book, ‘SOMEBODY TELLING SOMEBODY ELSE, Phelan creates a Criteria which he thinks would be more suitable for Understanding the Rhetorical Poetics of Narrative. Item 6 is particularly interesting for me because he Explicitly lays out something that I think is VERY IMPORTANT for the so-called ‘Culture Wars’, namely the Ethical Considerations regarding Telling Events. He writes:

“In addressing narrative ethics, rhetorical theory distinguishes between the ethics of the telling and the ethics of the told. The ethics of the telling refer to the ethical dimensions of author-narrator-audience relationships as constructed through everything from plotting to direct addresses to the audience, while the ethics of the told refer to the ethical dimensions of characters and events, including character-character interactions and choices to act in one way rather than another by individual characters. In keeping with the a posteriori principle, I approach ethics from the inside out rather than the outside in. That is, rather than using a particular theory of ethics to interpret and evaluate the ethical dimension of narratives, I seek to identify the system (whether coherent, eclectic, or incoherent) an author has deployed (consciously or intuitively) in the narrative.”

And so the Pragmatic Structure of the NARRATIVE ITSELF is a kind of Statement of Philosophy, which again, gets at the ‘Deep Implicature’ as to the RELEVANCE of a Sequenced Event to a Narrative Telling. And the funny thing is that Even When You Try to Defy the Canonical Expectations of an Anticipatory Convention you STILL Make a kind of Statement, even if it is seemingly ‘Random’ that Randomness STILL Asserts a kind of Statement regarding the Selection Process.

IN CONTRAST THEN to a Purely Meandering Text, I think that a Greater Attention to the Relevant Features of what Narratologist David Herman refers to as Canonicity and Breach, or University Professor Peter Stockwell from Centre for Research in Applied Linguistics in Nottingham refers to as Cognitive Schema, is perhaps a BETTER COMPOSITION TOOL than either the Inherited Traditions from the Analytics School or the Digressive Meanderings of Autofiction.

I will END THIS DISCUSSION with a Brief Discussion on the Reconstruction of Enthymeme according to University Professor James Fredal, which is NOT what he refers to as a Truncated Syllogism, but is Closer to a Marked Feature or, if I Recall Correctly, he Refers to as a ‘Noticed Indication’ within a Narrative Telling. It is in Fredal that I notice, and Returning to the Discussion on Digressions, a Correspondence with the Work of the German-American Academic Anselm Haverkamp, specifically with his more recent work on Poetics as being more Properly Understood as what he refers to as a ‘Productive Digression’. Thus I think that the Marked Features of a Narrative Telling such that they Provide for a Disruption or Disequilibrium to the Anticipatory Sensemaking of Event Sequencing, thus Providing for the Narrative’s Tellability.

(insert chef’s kiss gif here)

I don’t completely get it, aside from the meandering nature of the comment are there some other bits of context I’m possibly missing?

I think the standard template can be given an ethical defense along the following lines. Suppose I think I have some new philosophical contribution to offer to the community. Then (so *I* think, anyway) I owe it to my readers to explain that contribution in a way that puts them in an optimal epistemic position to critique it, and more generally to decide for themselves what to make of it and why. That’s actually very hard to do (in my experience): it means, for example, that I have to be on the lookout for key terms that I might understand differently from some of my audience, think hard about background assumptions I might be making that smooth my argumentative path in ways I might not have noticed, etc. But it’s ethically important (again, so I think). The standard template, along with other stylistic standards we tend to enforce in contemporary analytic philosophy, helps reinforce the ethical importance of treating one another with this kind of epistemic respect.

This seems to assume that the form or style in which I offer my philosophical contribution does not impact the contribution itself, so to speak. Yet it seems that, in some cases at least, the style is *part* of the contribution. I don’t think Plato would be as effective if he wrote in the traditional article format, for example.

Compare the efficacy of a dialog with that of an alternative (below). It would seem that the latter is more effective because it includes nothing irrelevant and properly focuses the reader on the argument itself, and this allows the reader to better understand and engage the relevant ideas. For example, the latter allows us to more easily pinpoint the claim(s) we want to dispute.

The Dialog

Me: Some would say that a philosophical contribution is nothing more than the novel idea, which might be put forward in a paper. The contribution, e.g., might be the new argument itself, the new distinction itself, or the new theory itself. Do you agree with those who would say this, Daniel?

Daniel: No, I most certainly do not.

Me: Well, if not the novel idea, then what is a philosophical contribution?

Daniel: Most people would say that it’s the presentation of the new idea, which includes the style in which it’s presented.

Me: I’m not interested in what others would say. I want to know what you say. Is this what you say?

Daniel: Yes, that’s what I say.

Me: Excellent! I’ve found someone in a position to teach me. And like my prior teachers, Daniel, you have left me with more questions than answers. The presentation includes more than the style; indeed, it could include such things as the paper, the ink, and the other things by means of which the new idea is communicated. Do you agree?

Daniel: Yes, of course, I do.

Me: Do you also agree that when a thing made of paper, ink, and the other things is utterly destroyed by flame, it’s transformed and lost, and if I were to try to re-create it using new materials, I wouldn’t have the same thing but an altogether different one?

Daniel: Must you insist on wasting time on trivialities?

Me: I’m trying see if I understand what you’re saying, Daniel. Anyway, I won’t ask too many more if you’d be so kind as to answer.

Daniel: Yes, you’d have an altogether different thing. I fail to see what this has to do with our discussion.

Me: Well, if my philosophical contribution were utterly destroyed by flame, and I later re-create it in every way except that I use new materials, would I have created an altogether new contribution? Or would it instead the same contribution?

Daniel: It would be the same.

Me: But how can this be? If the contribution were the presentation of the new idea, and the paper, ink, etc. were part of the presentation, then destroying these materials would destroy the presentation and, with it, the contribution, right?

Daniel: Apparently so.

Me: Since I wouldn’t be able to re-create the same presentation using new materials, I wouldn’t be able to re-create the same contribution. So, if the contribution is the presentation, then contrary to your earlier claim, the contribution I create using new materials wouldn’t be the same as the destroyed one.

Daniel: I see. It would seem that I was mistaken. Clearly, the contribution is not the presentation.

Me: What, then, do you say the contribution is?

Daniel: I’d be happy to tell you. But I’m very busy today, and unfortunately, I’ve run out of time. I really must take my leave.

Me: If you leave now, who shall teach me?

The Alternative

1. If the style is a part of a philosophical contribution, then the contribution is the presentation of a new idea.

2. If the contribution is the presentation, the contribution consists of, among other things, the materials used to present the idea.

3. If the contribution consists of, among other things, the materials used, then if the materials were utterly destroyed by flame, the contribution would be destroyed, and any attempt to re-create it using new materials would result in a new contribution altogether.

4. Even if the materials used were utterly destroyed by flame, the contribution wouldn’t be destroyed, and the same contribution could be reproduced.

5. Therefore: the style is not a part of a philosophical contribution.

I think this comment unhelpfully equivocates between efficiency in the sense of economy of words and effectiveness in communication. Sometimes the two go hand in hand. But I think many would concede that linguistic practices are full of redundancies whose function is to aid in overall communication of a point/meaning. So it can’t be necessary that economy of words goes hand in hand with effectiveness. In that case though, the case that needs to be made is that the effectiveness of dialogue format, in particular, is somehow always strictly dominated by the effectiveness of the alternative being endorsed. And an example (granting you it, for the sake of argument) isn’t going to be compelling evidence for the universal.

I take your point, but I’m not sure that particular counterexamples refute the overall argument being made, simply because the context of a tradition matters.

If I would write a dialogue, even if I did it as brilliantly as Plato did, instead of a paper in the style of contemporary analytic philosophy, I would not be as effective in communicating my intent.

Is the form of the dialogues more effective in demonstrating his theses or in making them compelling? (Please interpret this false dichotomy with charity.) If something closer to the former I am interested in hearing more about that.

I’m re-reading The Philosophical Investigations now and I don’t think it is really possible to present W’s “views”(the word itself is deceptive) without distortion. Evidence: the various quasi-behaviorist readings of some early commentators gave it.Some philosophy is about advancing positions based on argument, other kinds of philosophy are about coming to a better understanding of what we really know all along but have not reflected on it. Thus W: Look at what actually happens when you use a word. J.J. Valberg remarks. in his excellent _Dream, Death and the Self_ that philosophy really deals with coming to grips with what we already know…It’s a bold untrue statement if meant to apply to all philosophy, but it does apply to phenomenology. E.g. you may. not have explicitly thought “Ordinarily things are present to me not as mere objects, but as as “objects of use” (H’s ready-to hand) that are part of a system of signification that constitutes the world. That is a mouthful of obscure verbiage..but the phenomena that is being pointed to (not described) is not. It’s already there in our everyday experience. We just need to learn how to “see” it