In Defense of Boring and Derivative Philosophy (guest post)

“Even if you prefer the sexiness of radicalism or the glory of revolution: you need boring, work-a-day normal conservative philosophy.”

Yesterday, J. Dmitri Gallow (Senior Research Fellow at Dianoia Institute of Philosophy) tweeted out a thread on the value of what he labels “conservative, normal philosophy.” Finding it interesting, I asked him to turn it into a brief blog post for Daily Nous, which he very kindly did.

In Defense of Boring and Derivative Philosophy

by J. Dmitri Gallow

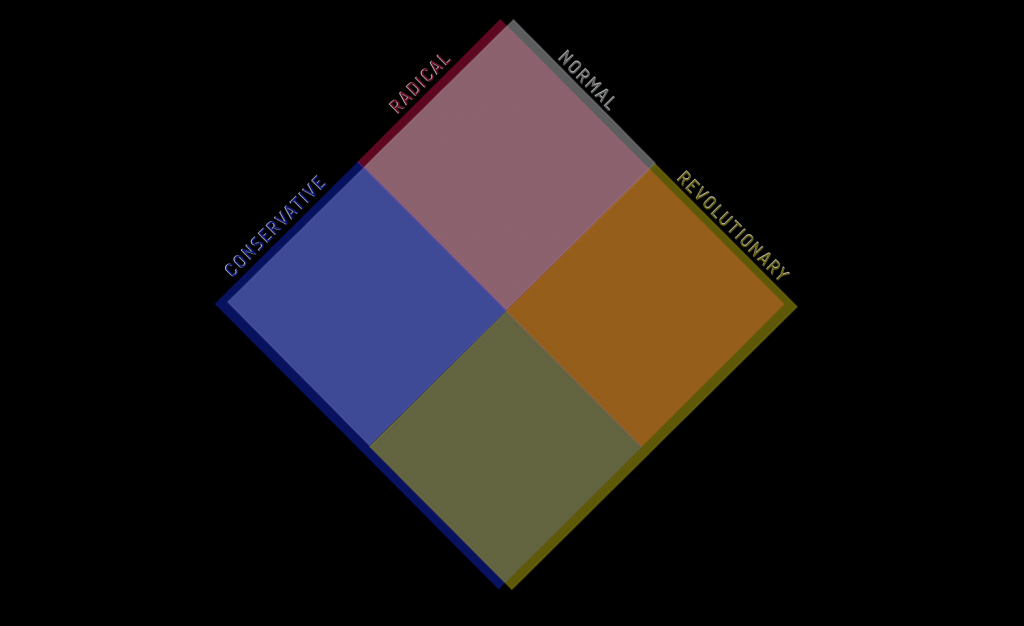

I often hear papers, talks, or projects dismissed as “boring” or “derivative”—contrasted with philosophy that’s “novel” or “insightful.” This dismissive attitude is usually directed at (a) work that’s conservative, rather than radical (in a sense I’ll explain below), and (b) work that’s normal, rather than revolutionary (in the sense of Thomas Kuhn). I think the dismissive attitude underestimates the value of normal conservative philosophy. Below, I’ll introduce these distinctions and defend normal conservative—and therefore, boring and derivative—philosophy.

As I understand philosophy, it’s an attempt to answer the question “How should we think about X?” for values of X where the question isn’t answerable by empirical investigation or demonstrative proof. We’re often led to philosophy by puzzles in which our unreflective ways of thinking about X are contradictory. For instance, we’re inclined to say that losing a single hair won’t make you bald, but we’re also inclined to say that some people become bald by losing one hair at a time. Once we notice that these things can’t both be true at once, we’re driven to philosophise; we attempt to resolve the puzzle by revising some of our pre-theoretic ways of thinking about things.

Some philosophy tries to resolve puzzles by doing as little damage as possible to our pre-theoretic, unreflective ways of thinking about X. Let’s call this kind of philosophy “conservative”. Other philosophy takes puzzles to reveal widespread systematic error in the ways we unreflectively think about X. Let’s call this philosophy “radical”. More generally, conservative philosophy defends views that hew closely to our ordinary thought and talk, whereas radical philosophy defends views that ascribe widespread and systematic error to our ordinary thought and talk. (Of course, the distinction between conservativism and radicalism isn’t hard and fast; philosophy can be more or less conservative, and it can be radical about some things and conservative about others.)

Conservativism is often boring. Conservative work solves puzzles by saying things like “everyday reasoning is good as a heuristic, and it’s almost always valid, but there are few outré cases where it is led astray, so a slightly more nuanced method of reasoning is needed. Let me axiomatise the proper logic for you”. If conservative philosophy is successful, you learn only that the ways you’re already inclined to think about X are, by and large, correct.

Radical philosophy is often exciting. Radical work solves puzzles in striking, surprising ways. It says things like “there’s no distinction between F-ness and the act of judging to be F”, “freedom is impossible”, “causation is a relic of a bygone age”, or “tables and chairs do not exist”. Radical solutions are intellectually thrilling; they have interesting and unexpected consequences for our thinking in many other areas.

I think something like Kuhn’s distinction between normal science and revolutionary science applies to philosophy, as well. Some philosophy attempts to articulate an existing, established way of thinking about X (the ‘paradigm’). It spells out the details, dots the ‘i’s, crosses the ‘t’s, explores consequences, and defends the view from objections and counterexamples. Call this “normal philosophy”. For instance, quite a lot of political philosophy over the past 50 years has been normal work developing the Rawlsian paradigm. Other philosophy is revolutionary. An existing, established view is challenged and a replacement proposed. For instance, I think of the emergence of quasi-realism 40 years ago as a revolution within expressivism. (Of course, as in science, the distinction between normal philosophy which articulates a paradigm by proposing a minor revision and revolutionary philosophy which upends and replaces the paradigm isn’t always clear-cut; there’s work that’s hard to classify either way.)

These distinctions cross-cut each other. There is revolutionary conservative philosophy and normal radical philosophy. For instance, I think of compatibilism as a conservative philosophy; it tries to conserve most of our ordinary thought and talk about freedom and moral responsibility. And within this conservative philosophy, the turn away from a conditional analysis of freedom towards a reasons-responsive analysis was a revolution.

Like radical philosophy, revolutionary philosophy is exciting and sexy. Both offer whole new ways of thinking about and understanding X. Radical or revolutionary philosophy feels relevatory and insightful.

On the other hand, normal philosophy is often boring and derivative. It is boring because it adds little to prior, familiar ways of thinking about X. And it’s derivative because it leans heavily on prior work articulating its paradigm.

My defence of normal conservative philosophy is this: it is needed to do both radical and revolutionary philosophy well. So, even if you prefer the sexiness of radicalism or the glory of revolution: you need boring, work-a-day normal conservative philosophy. (Of course, if a paradigm conservative view is correct, then I take it that normal conservative philosophy needs no defense. Since I take the goal of philosophy to be answering “How should we think about X?”, if the answer is given by the conservative paradigm view, then normal conservative philosophy is plainly needed to achieve the goal. So I’m just focusing on the difficult case in which some radical or revolutionary view is correct.)

Without knowing the best conservative options, it’s difficult to appraise radical views. Perhaps the puzzles show us that free will is impossible, chairs don’t exist, there’s no F-ness without judging to be F, or that there’s no such thing as causation. But unless we look at the less radical alternatives, how confident of this can we be?

Similarly, without examining the output of normal philosophy, you cannot tell whether revolution is called for. Perhaps the existing paradigm cannot satisfactorily deal with the counterexample or objection you’ve discovered. To figure out whether that’s so, you’ll have to consider the best attempts of the normal philosophers.

In general, deciding between different ways of thinking about X requires weighing the costs and benefits of the alternatives. But whether something is a cost, and how costly it is, is going to depend upon the menu of options. If every view on X has to reject some pre-theoretically plausible claim, then the fact that your view on X rejects a pre-theoretically plausible claim shouldn’t be held against it. So doing philosophy requires having well-articulated alternatives to appraise. Generating these alternatives requires conservative and radical philosophy both. And getting well-developed alternatives requires normal philosophy.

So conservatives should want clever radicals to challenge them. Fielding and responding to those challenges brings out the costs and benefits of their view. Likewise, radicals should want clever conservatives to rebut their challenges and stir up trouble for their radicalism. Normal philosophers should want revolutionaries to draw their attention to counterexamples and objections. Treating those counterexamples and responding to those objections is an important part of articulating their paradigm. And revolutionaries should want normal philosophers to offer the best paradigm response to their counterexamples and objections. Without this work, it’s hard to say whether revolution is called for.

In sum: even if you most prize radical, revolutionary philosophy, and even if you find normal conservative philosophy boring and derivative, you should still want there to be lots of boring and derivative normal conservative philosophy around.

A good piece!

Novelty gets published. So, even if the best arguments you know of are somewhat derivative, the stuff that gets published and rewarded is often really out-there arguments with weak foundations. I find that, in a small way, this undermines our search for truth sometimes.

Am I the only one who’s never heard anyone make such complaints? Obviously I hear people complain about boring philosophy. And I hear people complain about “epicyclical” philosophy, and of course that’s one way of being derivative and thus in one sense conservative. But I’ve never heard anyone complain that all or even most philosophy that is not radical in OP’s sense is boring or derivative.

From Ray Monk’s recent-ish article about G. E. Moore.

That sounds a lot like a complaint about someone doing philosophy that is not radical in Dmitri’s sense.

There have been many philosophers who rejected common sense for one reason or another, and for those reasons they might well object to nonradical philosophy, but that does not look to me to be the complaint that such philosophy is “boring or derivative.”

I’ve met many people who have complained in general terms that journals publish too much stuff that is unambitious, which they usually describe as either derivative or so worried about responding to the objections of others that the conclusion they come to is so qualified as to be not very interesting. I am sympathetic to the author of the original post’s conclusion, and I don’t think that journals really publish too much stuff that is objectionably unambitious — I do think that journals tend to publish a lot of “normal” philosophy and a fair amount of “conservative” philosophy (using the terms in the sense that the original post did). My belief is that some of the people who complain about the journals in this way are conflating philosophy that is boring or epicyclical with philosophy that is conservative or normal; of course, they don’t complain about normal or conservative philosophy as such, but I think that’s because once you make the distinctions the original post is making you won’t make this complaint about the journals. An alternative hypothesis is that the people I’ve met are live to these distinctions, but simply have a different opinion from me about whether most of the articles published in contemporary journals are epicyclical or derivative. I think that the original post does an important service in making these distinctions explicit and thus helping people who hold my opinions to distinguish between these two hypotheses when in conversation with others who disagree with us about the quality of a particular piece of philosophical work.

I can’t find it now, but I think that Micah Schwartzman wrote something along these lines in the early era of blogging…

Thanks for the post.

This might be irrelevant. But I think when people complain about “conservative philosophy”, they often have in mind the kind of analytic elitism that keeps reproducing itself in academic philosophy; when people complain about “boring philosophy”, they often have in mind the kind of philosophy that deals with problems that don’t interest them or the kind of philosophy that is overly technical but loses sight of what’s really important; and when people complain about “derivative philosophy”, they often have in mind the kind of philosophy that lacks an awareness of its own foundation or lack of foundation.

The kind of “boring” and “derivative” philosophy that you nicely defended here seems perfectly fine even to someone like me who tends to prefer “radicalness” and “otherness”.

Nice piece. Although “boring” can mean many things. Common sense can seem boring to a philosopher, but it can have many interesting effects on philosophical theories. For instance, when I engage in a practice unreflectively and smoothly with my environment, a subject-object or representational model is undermined. And with Russel’s “nurse” comment against Moore, I daresay that many “radical” theories would be undone when raising children.

From: https://www.smbc-comics.com/index.php?db=comics&id=2406

This sort of reads as a defense of professionalization and its impact, but that can’t be right. I can’t tell what the author is actually defending.

Maybe it is just deference to what X-phi reveals to be the intuitions of some group? Not sure which group though.

“Some philosophy tries to resolve puzzles by doing as little damage as possible to our pre-theoretic, unreflective ways of thinking about X. Let’s call this kind of philosophy “conservative””

Who are “we”? How would this bear on the majority of philosophers who do not really investigate what “our pre-theoretic, unreflective ways of thinking about X” are…unless the we is we who are already discipled into philosophy departments?