Reports from Striking University of California Philosophy Graduate Students

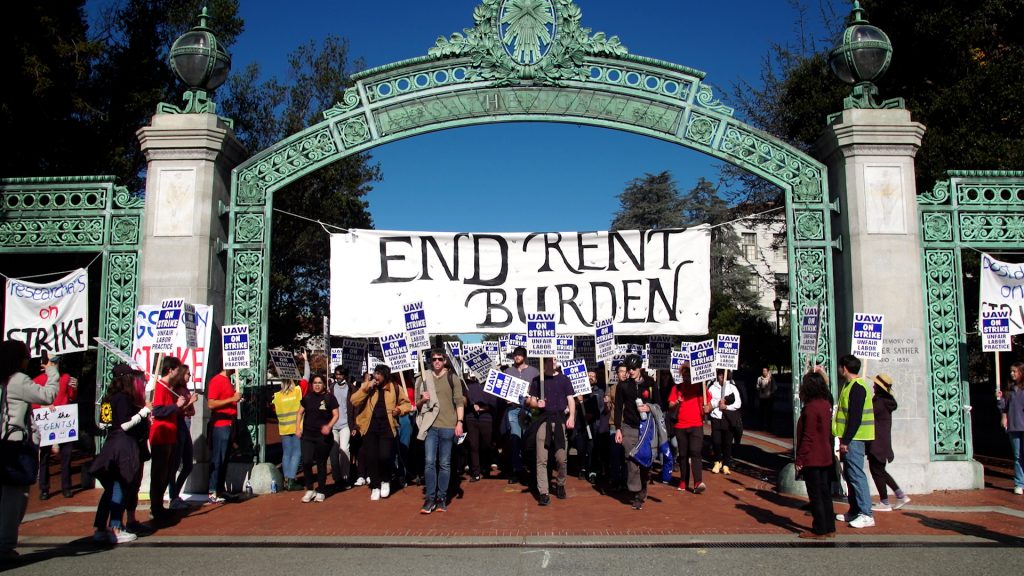

A strike by approximately 48,000 academic workers at the University of California’s 10 campuses is in its second week. The main issue is compensation, with graduate workers and others calling for major pay increases, improved parental leave and benefits, subsidies for public transportation, research funding, support for international scholars, and increased support for disabled researchers.

The following guest post was put together by Dallas Amico, a graduate student in philosophy UC San Diego. It includes comments from philosophy graduate students across the UC system and further information about the strike.

Reports from Striking University of California Philosophy Graduate Students

Laborers across the University of California system have gone on strike. Below you will find stories from philosophy graduate students who have gone on strike. You will also find information about the nature of the strike, why it has near universal support amongst union-represented workers, and about the University of California’s illegal behavior and woefully inadequate economic proposals.

Stories from Philosophy Graduate Students (part 1)

During my time in San Diego I’ve always spent more than 50% of my income on rent. My landlord recently raised my rent so I’m now paying about 75% of my income on rent. I simply can’t afford that. I’m trying to find a place to move, but it’s nearly impossible to find a place. Not just a place that’s safe or reasonably close to campus. It’s nearly impossible just to find a place, any place, that I can afford with my stipend. I work full-time over the summer and try to find ways to make extra money during the academic year, all just to be able to pay my bills. It’s undeniable that I would be a better philosopher and better teacher if I had been able to spend those countless hours doing what I came to UCSD to do instead of spending that time trying to survive. It harms grad students, our departments, the students we teach, our universities, and the discipline of philosophy as a whole when grad students are forced to spend inordinate amounts of time making extra money instead of focusing on our work. That’s why we need more money. ~ UCSD Philosophy Graduate Student

* * *

In my first year in the PhD program, I rented a room 25 miles away from the university where housing is cheaper. It was a 4 bedroom, one bathroom house with seven people living in it. I couldn’t afford a car, so my daily round-trip commute was 4 hours by train and e-bike. There weren’t public transportation options to get to and from the train station, so it was over 20 miles of biking per day round trip. It was exhausting. Because the commute took so much time, I would often leave the house at 5:30am and not get home until after 8pm. There weren’t many bicycle lanes on my route, and it was nerve-wracking to have to bicycle on the shoulders of busy roads in the dark. My daily commute also involved crossing a drainage ditch and climbing over a low chain link fence with my bike because the only alternatives were the freeway, where bikes aren’t allowed, or a 2-mile detour. I had hardly any time for my own research because in addition to the commute, I was the only TA for a class of 120 students in which I was doing more than the 20 hours per week that we are paid for.

When the pandemic started and the university switched to remote learning, I moved into a van. For about 6 months I either stealth camped along roads or parked on public land. When the logistics of finding a place to park every night became too time consuming, I parked outside a family member’s home in a different county. They have no driveway, so the parking spot is on a public road and living there in a van is illegal.

If I were paid more, I would rent a room instead of living in the van. The roof leaks and I have to cover it with a tarp when it rains. I constantly have to hide the fact that the van is being lived in. I still have a long commute because there aren’t places to park a van overnight near my university. It’s also stressful; vandwelling is criminalized in most cities in California and it’s mentally taxing to have a living situation that is technically illegal. I’ve had the police knock on my door twice. Living in a van means never fully “turning off”; you are always slightly alert, ready for someone to knock on your door and ask you to move.

However, I also feel very lucky to have the van, since the alternative is living paycheck to paycheck. Living in a van has given me a degree of financial security that I could never have while renting a room, even if I were to get off the 1+ year waitlist for grad student housing.

The current strike action has opened discussion about how many UC grad students are living in their vehicles. If the UC continues to refuse to increase wages, an alternative way for the UC to support its academic workers would be to create safe overnight parking programs for the employees who live in vehicles. Such programs have already been adopted by other California colleges like Long Beach City College ~ UC Philosophy Graduate Student

* * *

I am a graduate student and a teaching assistant, but I often feel like I have to choose between my well-being, my teaching, and my research. I have had to take on a second-job which takes away from my studies and my teaching. That being said, I am someone who is so lucky to have people who can support me financially if (and when) I need it. However, this is not the case for the majority of people and the lives of grad students shouldn’t depend on whether they have a support system like this. We all work so hard and we care so deeply about what we do. We should be able to feel like all this work allows us to support ourselves while also feeling appreciated by the university we work for. ~ UC Riverside Philosophy Graduate Student

* * *

One particularly difficult month, my 2003 auto needed a fairly expensive repair (~$500.00) and my dog needed veterinary care and medication for recurring seizures. (~$400.00). While these expenses may seem minor, they put me in a serious hole. I was unable to make rent after paying them, and I didn’t have anyone to turn to at the time. As a result, I was forced to explain my situation to my landlord and beg him to allow me to work for him in order to make up the difference. Fortunately, he allowed me to work for him. Immediately thereafter, I picked up a job as a part time landscaper, to avoid having to ever experience the humiliation of having to beg a landlord again. ~ UC Philosophy Graduate Student

About the Strike

This is an unfair labor practice strike (‘ULP’). The United Auto Workers union, which represents graduate students, post-docs, and undergraduate graders and tutors across the University of California, has filed 25 unfair labor practice charges against the UCs. The California Public Relations Labor Board has lent credence to 6 of these and filed complaints against the university; decisions remain to be made on numerous further charges. The university’s unlawful tactics include unilaterally altering working conditions, threatening retaliation to strikers, and refusing to provide information necessary to bargain.

As a result of this being a ULP strike, academic workers on strike have significant legal protections. For example, we can not be permanently replaced.

Notable facts:

- This is the largest current strike in the United States—the UAW represents 48,000 graduate students, undergraduate students, and postdocs.

- This is the first time in history that postdocs have gone on strike.

- 98% of members who participated in the strike authorization vote voted to go on strike.

- The California Labor Federation has sanctioned the strike—meaning 1,200 California unions support the action.

- The Teamsters union has also declared support for the strike (including UPS drivers), and will not cross the picket lines.

Facts on the ground:

Disclaimer 1. The following is primarily focused on the plight of philosophy graduate students although undergraduates and postdocs face serious issues as well.

Disclaimer 2. The following is primarily focused on the plight of philosophy graduate students at UCSD (as that is the case the author is most familiar with). That said, even though the exact details vary slightly across the state, what follows echoes true in spirit for graduate students across the UC system.

The current pay rates for graduate students from UCSD are as follows (we use San Diego as an example, but the facts are very similar across the UCs):

- Graduate Student Researchers (‘GSR’): $2,192 per month ($19,728 per 9 months)

- Teaching Assistants (‘TA’): $2,582.95 per month ($23,246.55 per 9 months)

(source)

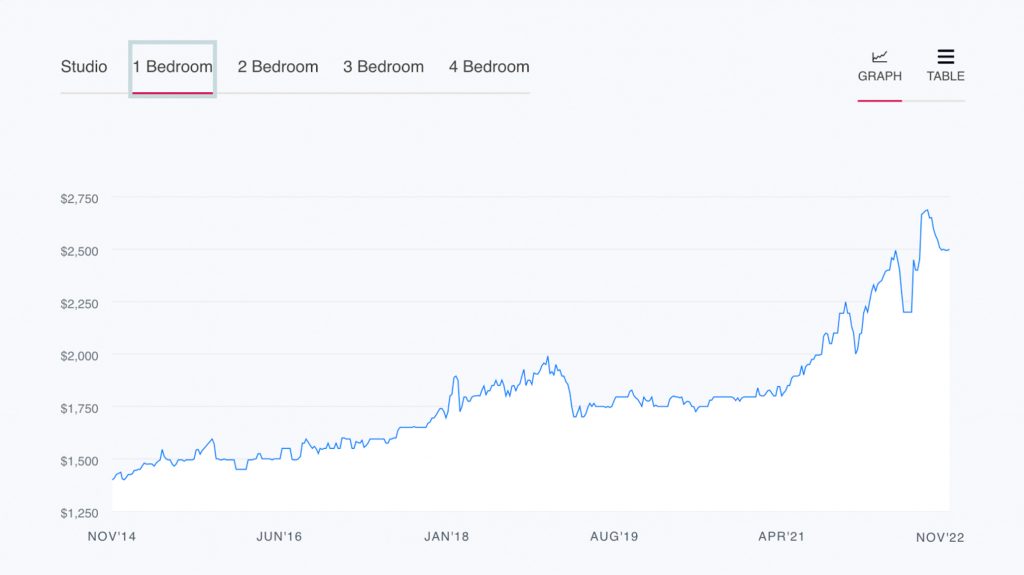

Those rates reflect the pay rates agreed upon in 2018 by the union and the university. At the time those pay rates were agreed upon, the median 1 bedroom apartment in San Diego cost ~$1,740 per month (per Zumper.com). Even at that time, it was extremely difficult for a graduate student to afford a 1 bedroom apartment in the city they’re asked to live in. But things have gotten significantly worse. San Diego’s rental market has spun out of control. The current per month price for a median 1 bedroom apartment in San Diego is estimated to be $2,500. This is a 4 year housing cost increase of 43.6%.

One thing the university has offered to some graduate students (there is not sufficient space for all graduate students) is subsidized housing. However, over the last 4 years, while graduate students’ rent checks have only increased by 3% each year, the university has increased the price of graduate housing by 35-85%. And many of these rentals supposedly for graduate students are too expensive for graduate students. As an example, a 480 sq. ft 1 bedroom apartment in UCSD’s Nuevo East apartments costs $1,977 per month. This is straightforwardly unaffordable given current salaries.

Given these facts, one might expect the university to make very generous economic offers at the bargaining table. Not only has the rental market in the city exploded (not to mention inflation), but, for those graduate students who live on university property, the university has begun taking back a significantly larger portion of their income. But UC has not done this. Instead, they’ve offered small increases and recommended that graduate students double and triple up in apartments, they’ve opened food banks on campus, and many graduate students have been encouraged to look into low-income housing (the city of San Diego deems any income below $27,350 per year to be “extremely low” and eligible for a wide range of poverty benefits).

More specifically UC’s initial economic proposal was for 4% raises the 1st year of the new contract and 3% raises thereafter. They have since increased those offers as follows:

- GSRs: On their current proposal “most GSRs will see 9-10% percent increases in year one of the contract, with a 3% percent increase in each subsequent year.”

- TAs: “Within 90 days from contract ratification, Teaching Assistants and Associate Instructors would receive a 7% pay increase; Teaching Fellows would receive an 8.33% increase. Hourly-paid ASEs would receive 5-8% increases. Next fall, TAs and Associate Instructors will be eligible for experience-based increases on top of their 3% increases annually.”

Even on this new proposal, the university is offering us a massive purchasing power pay cut. This is especially insulting for those students who live in graduate student housing. For those students the university has raised their rent by 35-85%, offered them a wage increase of 7-10%, and then repeatedly described their proposal as “fair and generous”.

It’s also worth noting a very obvious fact. In real dollars, 10% increases for GSRs and 7% increases for TAs is miniscule. On the university’s proposal GSRs and TAs should expect real dollar increases of under $200.00 per month, and per year raises of ~$1,800. These offers are pitifully low, and don’t even make it feasible for a graduate student to rent a small 1 bedroom apartment from the university.

These facts explain why the strike has near unanimous support amongst the union members.

Most of us want to get back to work. We applied for graduate school because we love to teach and we love to research and we love philosophy. But in order to do those things, we need to be able to afford basic necessities. We need to be able to afford modest apartments. We need to be able to afford food without having to rely on food banks. And we need a university that will bargain in good faith, and that will treat us with respect and dignity.

Below, you’ll find a number of further stories from current graduate students that emphasize the stress and difficulty of our current conditions.

Stories from Philosophy Graduate Students (part 2)

During recruitment, especially toward undergraduates, philosophers urge women, people of color, and other underrepresented people to apply to, and subsequently enter graduate programs to improve and diversify the discipline. This obviously often becomes extra labor through service to the department and the discipline (which many of us do indeed take on gladly because we love philosophy!). But this recruitment becomes especially disheartening when we get to graduate school and come to see that much of this has been lip service to an ideal that many in our discipline refuse to take more action to realize on a systemic level–such as by supporting our strike. When we cannot afford housing, groceries, childcare, and decent standards of living, all that support of us ‘underrepresented’ folks starts to ring hollow. I truly love philosophy and am committed to contributing to my discipline. But how can I believe that I, and others like me are truly valued, let alone respected when my peers and I cannot afford to live? ~ Woman of Color UC Philosophy Graduate Student

* * *

With my spouse and I having suddenly separated, I had to face the harsh reality of having to pay four grand to live in a one bedroom apartment (including utilities) by myself. Although I managed to secure a place to live, my new apartment is nonetheless exorbitantly expensive and swallows up my entire paycheck. Without the support of my parents, I would incontrovertibly either be living out of my car or couch-surfing ~ UC Philosophy Graduate Student

* * *

Faculty members in our department have told graduate students that we should not expect to make a living wage while in the program since our appointment is only 50%. As an international student, I am not allowed to get a second job. As a person whose financial background does not include generational wealth, I cannot rely on my family back home for financial support. Remarks like this are not just insensitive, they are heartbreaking. Their direct implication is that international students who are not financially well-off should not pursue a philosophy Ph.D. at UCSD. To me, they also mean that the people I look up to think I should not be in this program. ~ An International UC Philosophy Graduate Student

* * *

The rent for the “university sponsored” graduate/family housing was more than $1500, and my monthly income was $2100 — excluding Summer. I am an international student, so I can’t take up any jobs off campus, due to visa restrictions.

The financial burden meant that I had to move back in with my family (outside of the US), and I’m now continuing my PhD (I’m ABD) remotely. This year, I was able to use my one-year fellowship that I was offered with my acceptance letter. At least this means I can pick up other part-time jobs to fund my PhD. This was the only way possible since the non-resident tuition fee waiver expires 3 years after candidacy, and so I must defend my dissertation before it expires.

$600 a month is not really a liveable cost for an international student with a family. If we want to see our relatives and survive the summer, we have to be saving throughout the 9 months when we have some income. When I need to TA again after the fellowship, I don’t know yet how it will be possible. I just hope that I can finish my dissertation this year, so I won’t have to return to campus to TA. ~ UC Philosophy Graduate Student

* * *

With a stipend of $24k, my average monthly income is 2k. My rent is $1235/mo. (I share a 2-bed apartment with a flatmate, 50 mins public transportation away from campus.) That leaves me $765 each month to pay for everything else: electricity and internet, meals, medical bills, car (insurance, gas, on-campus parking), everyday supplies (shampoo, tissue, etc.), books, and money saved for conference travels not covered by department travel fund, and other unexpected small expenses. It’s an impossible financial juggle. I can’t take a second job because it messes with my international student visa. I didn’t take summer TA jobs because they are often heavy workloads and I really need time for my own research.

Earlier this fall, my apartment had a water pressure issue due to our old building’s outdated plumbings. For two months, I had no usable running water in the kitchen and unstable water in the shower. I had to get takeout much more often and a few times skip shower or shower in a friend’s place or the university gym. I thought about moving out, but then realized I couldn’t. If I move to on-campus housing, it will be cheaper (~$950), but the waiting list is for months, and after 14 months I have to move out to off-campus again (The university has a 2-year time limit for grad housing and I’ve used 10 months.) But then with my income I won’t pass any landlord’s income check for a new tenant. At least for the landlords in areas safe for a single woman to live. I am able to stay in the current apartment because of an outdated income record. I have no intention to ask and make the leasing office notice it as long as they don’t ask me ~ UC Philosophy Graduate Student

* * *

I live with a chronic medical condition that has a number of associated costs (e.g. medical care not fully covered by insurance). After I pay for housing and medical care, I have ~$600 to pay for everything else each month, including food, transportation, school supplies, etc.. Faculty, please look at your own monthly budgets and try to imagine what it is like to live this way.

A living wage for my county is defined as more than twice my current compensation (see this site for information about living wages in different California counties). Earning a living wage for my area would be life changing. Striking graduate students are asking only to be treated as human beings rather than as sources of cheap labor. Please support us. ~ UC Philosophy Graduate Student

How to Follow and Support the Strike

Ways to keep up to date on the strike:

Ways to support or get involved:

- Respect the picket line. What this means:

- Don’t pick up labor that union members have struck (e.g. don’t grade papers that graduate students ordinarily would).

- FAQs for UC faculty from The Council of UC Faculty Associations

- UC-AFT 19966’s guide for strike solidarity (for UC lecturers and librarians)

- Don’t give or attend talks on UC campuses.

- Postpone or move conferences scheduled to appear on campuses.

- Don’t pick up labor that union members have struck (e.g. don’t grade papers that graduate students ordinarily would).

- Donate to the UAW hardship fund.

- Sign the petition to President Drake.

- Support workers and unions that support us!

- Use your platform to raise awareness, and encourage others to respect the picket line.

We UC grads would appreciate public statements of support from philosophy departments around the country. Does anyone know which departments have offered such letters?

A letter of support from UC Davis philosophy faculty is here: https://ucdavis.app.box.com/s/hfsh5thkf634qqk6f0kgk3aalceitt65

When I did my PhD at UC, I had few complaints but the income is extremely low for the rent. I know someone who lived without front teeth for two years because they could not afford to get them fixed. It was far worse if you had dependents, anyone with children was either supported by someone else or dropped out. Really the question being asked here is: do we want PhD programs to be open to those capable of completing one or only those who have an independent source of income?

I hope this opens the eyes of UC Phil Faculty. We should not be begging faculty to support us, to have them come to our picket line, not do struck labor, not say awful things to us, or help us organize. Faculty lose nothing by showing up on the picket line. Faculty lose nothing by giving us accommodations in seminars. Faculty lose nothing by canceling talks or reading groups that cross the picket line. And we should not be giving to philosophical reasons or justifications as to why. The lack of compassion and empathy that has been shown is appalling.

I was told at the beginning of this to quit my job because I should be dedicating myself full time to philosophy. I am glad I never listened or else I would be homeless. Instead, I still live paycheck to paycheck, stressed and exhausted working a job on top of my TA job and grad school. I would LOVE to quit my job to do full time philosophy but I do not have the generational wealth to do that. (Which emphasizes how hollow the DEI statements and initiatives truly are)

I was a grad student at UCSD from 2011-2018 and I was lucky enough to get a SHORE Fellowship. I can’t remember what the acronym stands for (I think the H is for ‘housing’ and the R is for ‘research’) but what it does is it lets you stay in grad housing your whole time if you want: otherwise they kick you out after 2 years. At that time grad housing was ~$575/month (and it went up each year – it was ~$6XX when I left) which is half your paycheck but still way below anything else you’d ever rent in San Diego.

(Unfortunately, while I was there, they knocked down most of the grad housing and built new housing like the “Nuevo East” mentioned in the article, which has much smaller rooms than the old grad housing and which costs much more.)

It would’ve been pretty hard to make ends meet without SHORE, and even with SHORE, the new housing rents would’ve made things even tougher. I have no idea how existing UCSD students can make it work given how high rent has gotten in the past few years.

My time at UCSD overlapped with Danny’s (I started not longer before him; I left not long before him). I remember having a conversation with a different classmate in our mutual first year, where we tried to figure out whether anyone was able to do grad school at UCSD without supplemental money. Many people had external scholarships, family money, savings from prior careers, worked doggedly over the summers, and the like. And that was before the incredible growth in cost of living in the years since I have left. I had a one bedroom in a transit-commutable neighborhood for $800, and it looks like rent has now about doubled for that place. (Graduate student support, unsurprisingly, has not doubled in the same time.)

I was fortunate to find significant external income (tripling my annual income), and then I dropped out of UCSD while dissertating to adjunct at USD (maintaining that tripling number). I am not sure that graduate school in San Diego without those opportunities, opportunities which few graduate students have. And I am sure that the significant time commitments involved made my research work both more sporadic and less productive.

To all the Americans reading this thread, particularly those in a position to pressure their institutions into making substantive changes: It can be different. There are models abroad (ex., Scandinavia) that I sincerely hope you can use to persuade your administrations into believing that they should — and evidently can — actually value the labor of their PhD students and postdoctoral hires in the only way that really matters, which (as unromantic as this might sound) is getting paid.

Our work deserves fair compensation, and in some cases far better than fair compensation when the work stands to make a significant original contribution. Unfortunately, this might require American departments to scale back and reconsider one of the things that sets them apart, which is the wonderful cohorts of students they bring into their universities with each round of PhD applications. The problem is that departments see these cohorts primarily as a pool of cheap labor, as opposed to a group of persons with the potential to contribute much to each other’s projects and to the community at large during their time in the program. As long as departments conceive of these students first and foremost as cost-saving resources for the university, they will not ask themselves just how many students they can actually afford to hire at a dignified wage.

Just to put it into perspective: At some public universities in Scandinavia, the average PhD candidate makes almost $50,000 per year. Tuition is free because you are seen as the lowest ranking member of a faculty, as opposed to a (mere?) student. I know there will be people in the comments who insist that something like this isn’t structurally possible in the United States, let alone in the University of California system, but the point of my comment is not to speculate or quibble about the logistics of making such changes. It is simply to make it known that it doesn’t have to be this way, and that it is in fact not this way in all parts of the world.

Obviously, it doesn’t have to be that way. But how many PhD students do departments have? And what are the salaries of faculty? You have to take into account that the PhDs are paid for 6-7 years, count anywhere from 4-10 a year in a given department (so usually it’s about 40-60 active PbDs), are paid US style benefits (i.e. US level insurance cost which is insanely high) and the faculty are paid a lot – average is about 150.000 a year, more well known faculty get 170.000-240.000, some get to 300.000 and there are many of them.

I am currently applying to graduate school and working as a researcher at UCLA. Given UC’s current financial package, I worry about my future financial situation. I know graduate students across the UC system who are homeless and food insecure. Of course, I am hopeful that the strikes will bring about substantial change. Yet, I can’t imagine how many philosophers could never reach their full potential since their energy was focused on suriviving. This is especially disheartening for students like me who grew up poor with no external help. I fear that I will be one of the students who experience homelessness and, worse, never get to realize my full potential.

These stories are terrible to hear, although familiar to anyone who knows working class people in California, who have all been hit by the steep rise in rent. Given the financial situation of the UC (https://www.abc10.com/article/news/local/california/calmatters/can-uc-schools-afford-to-lose-out-of-state-students/103-716952ff-97e3-4219-b2bd-d35177243c60) and the state (https://calmatters.org/newsletters/whatmatters/2022/11/california-budget-deficit/) I am confused about where union members think this money will come from. To me the only likely source is tuition hikes for undergraduates, who are in a more precarious situation than graduate students (https://calmatters.org/explainers/california-cost-of-college-explained/). Undergraduates make around $15 dollars an hour for their work, whereas graduate students make around $25. (The current offer is for between around 24 and 30 dollars an hour; lecturers start at around $30 an hour). If the offer for graduate students goes up higher, their hourly rate will overlap with lecturers, who already have a PhD and teaching experience. While it might be nice to think their rate will go up, and then that of the faculty who are paid only a bit more (their hourly rate starts at $34 an hour, below market rate: https://archive.kpcc.org/blogs/education/2012/08/09/9358/report-UC-teachers-underpaid-paid-less-than-peers/), it is much more likely that graduate students will start to be replaced with lecturers. I, too, would like to see the UC better funded, see the housing crisis in California fixed. I am not sure how this strike is supposed to do that.

The point of a strike is not always to achieve a definite goal in a clearly delineated way, let alone to do so within a short timeframe. In this case, it is absolutely ludicrous that the persons who are victimized by this system should bear the onus of expertly creating the very solutions that they have every right to demand from the people who are exploiting them.

Well, there is of course an obvious way, namely make faculty and admin salaries (that is,.management salaries) more equitable. In Germany and many other places, a grad student might earn half or max. one third of what the professor (depending on case) does. In US, UC including it’s more like 5-6 times less, Dean’s earn around 300 and Chancellors 400.000. So bring the grad student and other salaries up and the rest down. Alternatively cut the number of grad students. None of this will of course happen. Our solidarity goes only that far. The low pay of a large number of cheap teachers is built into the whole system.

The last sentence is sort of true but also sort of not. TAs receive very little pay but cost the university a great deal. They are not cheap sources of teaching. Without them the university could pay pretty good wages to career teachers who could teach on a 2-2 or 3-2 or 3-3 load, and be spending (much) less per undergraduate credit than they spend for TAs. Of course in that case faculty wouldn’t have graduate students to teach (so they could teach more undergraduates and that would be a further saving). It’s true that the model of low paid teachers is built into the system but those low paid teachers are not cheap teaching labour at all.

(By the way deans in the UC system earn up to $800k. I don’t know any UC deans but none of the Deans I know is overpaid for what they do, relative to either TAs or Faculty, but especially relative to faculty).

Just to be clear the whole situation sounds desperate and I completely sympathize with the strikers (I have good friends striking). I don’t quite get why the demand is salary, rather than straightforward housing benefits, given that this is driven by rents.

One option for UC will be to negotiate (with the legislature) permission to enroll a much larger proportion of overseas and non-CA undergraduates, who will pay much higher tuition. (And of course whose presence will drive up rents further, but that effect will only be significant in smaller places like Davis and nearby the campuses in larger towns).

As Chair of the Philosophy Department at UC San Diego, I write in full support of our graduate students in their efforts to gain fair wages.

Our department has been greatly concerned about this issue for a long time. We recognize that graduate student funding has not kept pace with rising costs, especially the cost of housing. While not nearly enough, we have worked hard in recent years to provide more income for our students than the UC GSR and TA scales reflect. For the past two years, incoming students at UC San Diego have received a funding package of $30,000 per year made up of at least $24,000 during the 9-month academic year and a combination of TA’ing and stipends of at least $6,000 during the summer. For the past several years, our department has guaranteed an income of at least $24,000 through TAships and stipends with opportunities to earn more in the summers, as well.

These funding packages, while better than the minimal pay scales, have not kept up with the increased cost of living we have experienced in recent years, and we will continue to support graduate student efforts to secure better wages and benefits.

Sincerely,

Dana Kay Nelkin

Professor and Chair

Department of Philosophy

University of California, San Diego

It seems like there are a couple of issues being run together here – that of appropriately compensating someone for their labor, and that of providing stipends sufficient for someone to live reasonably and independently while in graduate school.

It’s seems a bit odd that researchers are compensated less well than TAs, since the former can be contractually required to work up to 20 hrs/week, while the latter likely come no where close to that number (at least in philosophy).

I suppose one must use whatever leverage one has at hand, but unless non-TA-related activities, such as one’s studies, are considered as part of a grad student’s labor, the claim that TAs are under-compensated (on a per/hr basis) seems strained.

Better to argue that stipends should be higher, just because it costs something to live while going to grad school. Admittedly, that won’t be a basis for an unfair *labor* practice strike.

So, I will go ahead and express the same sentiment as you, ajk. When I was a grad in a state university the US (not particularly well paid at all), my hourly wage is almost 45. While I was in the union, I didn’t really get the sentiment that grad students are being exploit. Well, this is true in some sense, but the pay is decent comparing to many other positions, including lecturers. In Europe, student spent a lot more time “working” rather than studying, so I don’t know how the hourly rate compare…

But I am really sorry for everyone who is having difficulties. I myself is also currently badly paid, and want to bargain for a better one, so I can relate.

I think the problem for grad students is that, generally, they do not have any other income than what they get as TAs (certainly at state schools, esp after 1st year) and they are expected not to really engage in other money earning activities, as the rest of their time (when not TA), is supposed to be study and research). The issue is that the current money they get, at least at UCs I’m California is not livable. If you get around 1400 a month, and you have to pay 1000 rent, you can’t really make it. The universities charge around that sum for housing (if you can get university one which is rare) and that’s just too much. 400 is very little these days even just for groceries in California.

Sorry for keep pushing back even though I agree with the basic spirit. How many people get as little as 1400 a month in CA? I thought it is more like 2500 a month. Rent is also higher, of course. Right? But maybe you are just trying to make the point rather than the numbers.

While I appreciate the distinction, I don’t think these issues can be clearly separated in this case – or at least we’d need to be clearer on what we mean by “fair”. That’s because whether compensation is fair would depend on how it compares to cost of living in the relevant region, given that that’s what determines the actual value of that compensation.

Your comment about the difference between RAs and TAs suggests that maybe you’re talking instead about fairness in the sense of whether the ratio between the compensations of two workers in the UC system matches the ratio between the value their work produces/amount of work they do. But that seems to me to be the wrong notion of fairness to apply here, since that sort of fairness would be compatible with everyone being massively underpaid.

Sorry, to clarify, in that second paragraph I’m talking about a notion of fairness where if W(x) is the amount of/value added by x’s work and C(x) is x’s compensation, then the degree to which worker a is compensated fairly/unfairly depends on the difference between C(a)/W(a) and something like the average across workers in the UC system of C(x)/W(x).

I agree that TAing or grading, and honestly even teaching a single class, takes up too little time to be classified as a full time job, so that the operative concern shouldn’t be a matter of grad students being adequately compensated for that labor. A major skill to be learned early in the program is the art of making the teaching duties as lightweight as possible, after all.

But what grad students should be demanding is the right to not live in constant financial insecurity for the 5-6 years of their PhDs. Grad students are an integral part of a vibrant active university, and their lack of financial security at ridiculously wealthy universities with money to throw around at any number of trivial causes is indeed an injustice worth being protested.

I got some help from my parents in grad school: I moved a few times and they paid my first/last (getting that chunk of change together is hard with moving costs; very hard); if I flew home rather than drove they’d usually cover my flight. Stuff like that. Really helpful and kind.

I still worked each summer though (the first three in straight up manual labour; the remaining few teaching/dissertating), and supported myself year-round by renting rooms (rather than apartments), rarely buying drinks out, packing lunches, etc.

When school would resume in September I’d marvel at some others’ summer activities: Norway, conferencing, Eastern Europe, whatever. We all made the same amount and they didn’t work in the summers. So family money was likely common.

Here’s where I get normative: why do you think you should not work when you’re able to and do not have the money of your own to live on? Struck me to be in bad taste. Plus, you get too used to that lifestyle you’re gonna crash if your philosophy PhD lands you in the economic gutter.

If you want to make it in academia, working another job is almost certainly going to be detrimental to your prospects. I’ve had a variety of side-hustles in grad school, mainly tutoring and some freelance writing, but I think working a full-time job on the side would jeopardize my ability to do quality work, attend conferences, and the like.

I don’t disagee with any of what you wrote. I’ll just add that some are able to work full-time, complete the dissertation, and write publishable papers during grad school.

Not sure where a second full-time job enters the picture. I didn’t work during the academic year because my full-time job was being a student/teacher. But when my funding lapsed in May or whatever I had to get another job to make it up.

So one full-time job September-April; a different one May-August. The alternative is that people who can ‘make it’ in academia are cossetted by family money in the summer, and academia becomes even more of a country club than it already is.

Oh my bad, I misunderstood what you were saying, and I totally agree with your point.

Shouldn’t one job be enough to live on?

Should be, yep. See above. I didn’t mean to say I worked two full-time jobs at once.

I’m unsure a sufficient processing of this information occurred, based on current comments.

One story clearly provides an acceptable ultimatum for the individual as: either give TAs more money or allow TAs to continue living in their cars, but legally on campus property.

Or rather, pay TAs or accept they’re houseless but let them stay on campus and continue being exploited.

Truly missing the mark by empathizing via anecdotes of days past when a room, parents, etc. made ends meet for oneself in an economy that’s markedly different from previous years or decades.