A New Topography of Philosophy: Analytic, Continental, and Philosophy of Science

When it comes to mapping the territory of academic philosophy, “the timeworn analytic-continental divide should be replaced with a three-way split, between analytic, continental, and philosophy of science programs.”

That’s Pablo Andrés Contreras Kallens (Cornell), Daniel J. Hicks (UC Merced), and Carolyn Dicey Jennings (UC Merced) in a new paper, “Networks in philosophy: Social networks and employment in academic philosophy,” published in Metaphilosophy.

Given disputes over both the substance and usefulness of the analytic-Continental distinction, the authors asked whether “other divisions might be more informative.” They used cluster analysis on data collected by Academic Philosophy Data Analysis (APDA), to investigate:

In machine learning, cluster analysis is any method that arranges units of analysis into subsets—that is, clusters—based on some measure of similarity between the variables that characterize them… In the current project, the units of analysis are philosophy Ph.D. programs, and the variables that characterize them are aggregated from (1) the areas of specialization (AOS) of their Ph.D. graduates and (2) the “keyword” survey responses. Recall that the survey respondents are asked to select keywords that distinguish their Ph.D. program. We hypothesized that if the analytic-continental divide exists at the departmental level, it will create patterns of association among these AOS and keyword variables and thus that the programs will cluster along this divide.

They found:

While there is a prominent split in the field that might be described as reflecting the analytic-continental divide, there is significant overlap between the two sides of this split. This might be, in part, because historical and pluralist programs tend to include both traditions. Further, splitting the field into three groups provides a better overall group structure according to at least one measure; on this picture, philosophy of science is distinguishable from both analytic and continental philosophy.

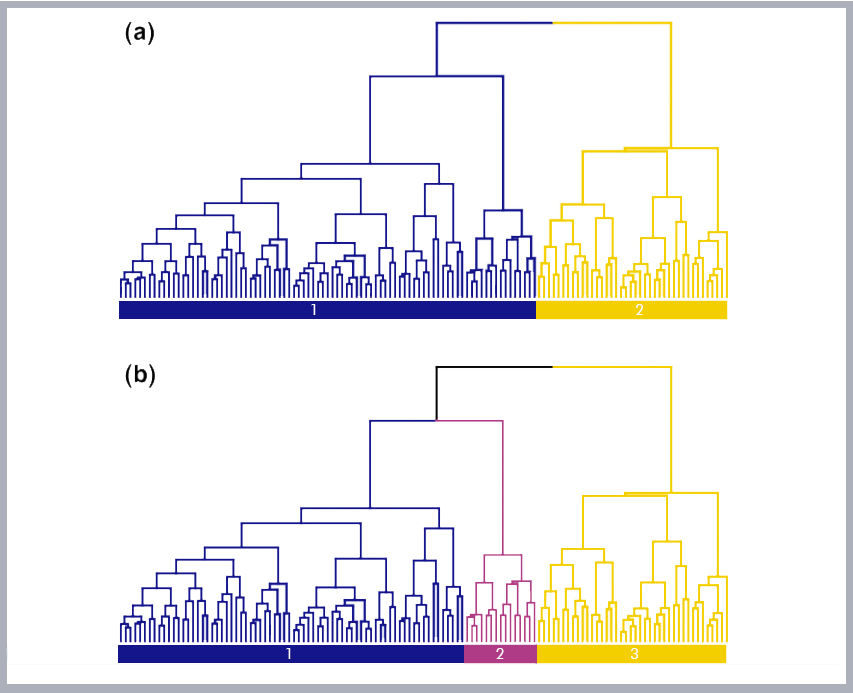

The team tried their analysis with PhD programs sorted into multiple numbers of clusters, from 2 to 10 clusters, determining that the data points were “better grouped” when limited to 2 or 3 clusters. The following figure (a modification of their Figure 3) shows the structure of the clusterings when the programs were sorted into two clusters (part a) and three clusters (part b):

In (a), Cluster 1 (blue) includes 87 programs and Cluster 2 (yellow) includes 40 programs. Here are the positive trait keywords for Cluster 1: Analytic, Naturalist/Empirical, AOS Mind, Mind, and Logic/Formal. Its negative traits are: Continental, Phenomenology, AOS Continental, Critical Theory, and German. In Cluster 2 (yellow) of (a), these traits are reversed: the positive traits for Cluster 1 are the negative traits for Cluster 2, and vice versa. The authors write: “based on these traits, this clustering appears to correspond to the analytic-continental divide.”

Regarding (b), the authors say:

the “analytic” cluster separates into two sub-clusters. The first [blue] of these two now includes 72 programs, and the second [dark pink] includes 15 programs; the “continental” cluster [yellow] is unchanged… with 40 programs. The positive traits of the first cluster [blue] are now keywords Analytic (0.43), Mind (0.38), AOS Mind (0.35), Epistemology (0.28), and AOS Metaphysics (0.25). All of these fall under the LEMM AOS category. The positive traits for Cluster 3 [yellow] are the same as the 2-cluster solution: Continental, Phenomenology, AOS Continental, Critical Theory, and German. For the new Cluster 2 [dark pink], the positive traits are Biology (2.18), AOS Science (1.88), AOS Biology (1.71), History and Philosophy of Science (1.44), and Naturalist/Empirical (1.42). This cluster appears to correspond to philosophy of science. When we use these clustering methods, philosophy of science is closer to analytic philosophy than to continental philosophy, but it is clearly distinguishable from analytic philosophy. This analytic philosophy/philosophy of science distinction is highlighted by the negative traits of [the philosophy of science] cluster, which include AOS Ethics (−0.65) and Mind (−0.57).

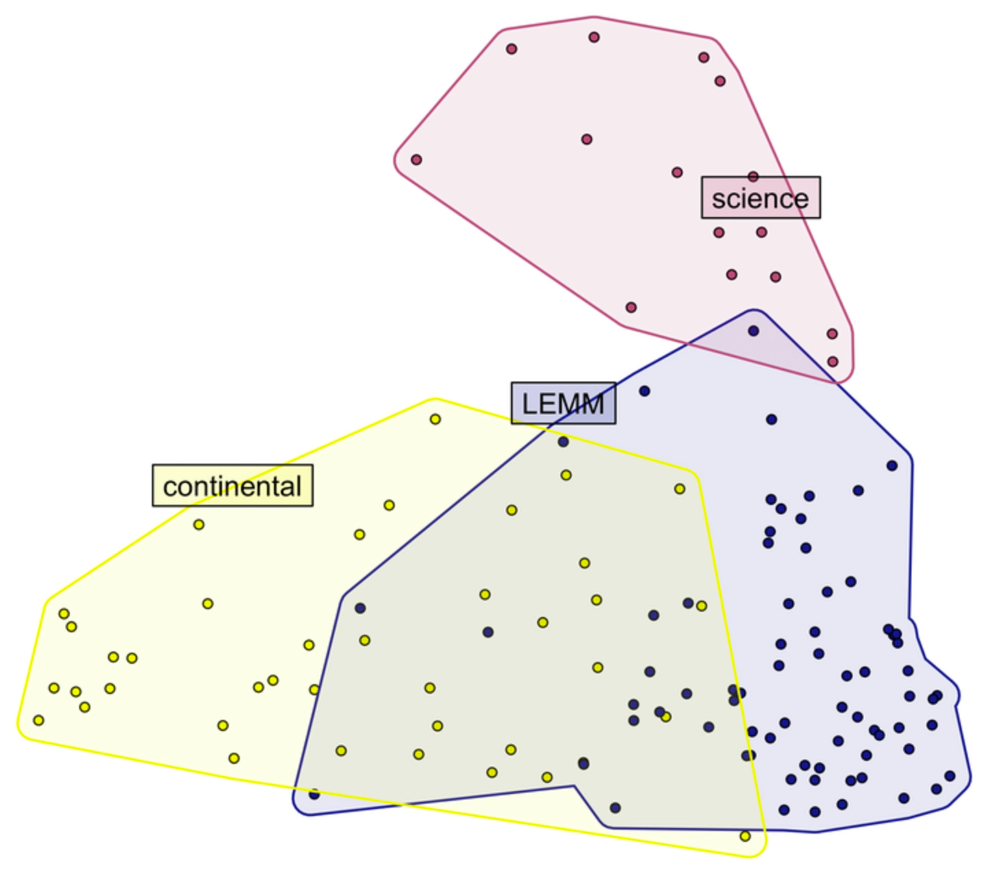

Here’s another color-coded visualization of the clusters as indicated in (b), above. In it, “each point represents a single program… On average across all pairs, Euclidean distances between these points approximate the correlation distance between programs, used to construct the clusters”:

The authors write:

This three-way split provides a better overall grouping structure than the two-way split and sheds light on what is a highly unified set of programs—the philosophy of science group has minimal overlap with the analytic and continental groups and should be considered a distinct entity.

Further analysis by the authors indicates that the Continental grouping depicted in yellow in the above figure actually is characterized by “substantial heterogeniety” evidenced in three subclusters:

One, with 15 programs, has the same traits as the [overall] “continental” cluster. A second cluster (17 programs) has traits Historical (1.26), Medieval (1.16), AOS 19th/20th (1.04), AOS Medieval/Renaissance (1.00), and Religion (0.93). And the third (8 programs) has traits AOS Applied Ethics (2.24), Gender/Feminist (1.87), Applied (1.40), Bioethics/Medical Ethics (1.27), and Political (0.97). To us, this array of clusters suggests that the “continental” label… might be an oversimplification. The [yellow] cluster seems to include not just “core continental” programs (phenomenology, 19th- and 20th-century French and German philosophy) but also work on the history of philosophy—especially the kind of historical work done at some religious-affiliated programs, such as the University of Notre Dame and Baylor University—as well as a practical, applied, feminist tradition. In short, and in line with the discussion above, this cluster analysis suggests that there are multiple, somewhat distinct “nonanalytic” traditions in anglophone academic philosophy.

You can read more about their methods and findings in the full paper, here, which includes analyses of the role of prestige and gender in the philosophy profession.

The analytic/continental division is largely methodological, whereas philosophy of science is of course distinguished by its subject, not its methodology

That’s true for some parts of philosophy of science, but not all. There is a lot of overlap in subject matter between philosophy of physics and metaphysics, between philosophy of psychology and philosophy of mind (and also between philosophy of biology and philosophy of mind), between history of science and history of philosophy, and between work on scientific methodology and epistemology. In lots of these cases there is a more pronounced difference in methodology than subject matter.

That’s not to say that the boundaries are clear, or that no one lives in both camps. (The same is true for analytic/continental; the boundary-lands are blurry and inhabited.) But it is to say that in a lot of cases, the difference between LEMM and Philosophy of Science is as much who one cites, which arguments/positions one takes seriously, which moves are allowed, and more generally the vibes, than it is the subject matter.

Right! Anecdotally, I have moved from continental (undergrad) to analytic (grad) to phil of science (after grad). My personal experience is that the difference between the latter two is much smaller than the first two, but still pretty perceptible. Phil of sci is far more driven by empirical considerations and resort to scientific methods more often (e.g., modeling, survey, data analysis, mathematical language).

Three clusters is an interesting proposal. However, I propose that philosopher is best seen as divided into negative one clusters. (If you do not understand this proposal then you’re probably in the wrong cluster.)

It’s a pretty odd clustering that puts Chicago, Columbia, Illinois, and Notre Dame in the same group (4, at the finest grained level) with Fordham, Duquesne, Catholic U, and Marquette.

Yes indeed! I was thinking that too. I skimmed quickly, so I didn’t quite figure out whether it was entirely driven by clustering based on who hired whom, or whether it was partially (or even entirely) driven by keywords in job ads. Regardless, it’s not totally surprising that a clustering based entirely on hiring (rather than publications), and forced into a tree structure (rather than something more multidimensional or Venn diagram like) has some odd features.

Keywords used by graduates to describe the program and the primary AOS of past graduates/current students.

This might just be because I work mainly in the history of philosophy, but if I were going to propose a tripartite division of the field as it stands, I would propose (1) analytic, (2) continental, and (3) history of philosophy. The reason – though I recognize this is purely anecdotal – is because folks who work in the history of philosophy seem to me to be more resistant to bring called either analytic philosophers or continental philosophers than folks who work in philosophy of science. Put another way, philosophers of science strike me as happier to present themselves as specialist within the analytic or continental traditions than scholars who specialize in ancient, medieval, early modern, etc.

Does that seem right? Does it even matter?