Do Men and Women Philosophers Argue Differently?

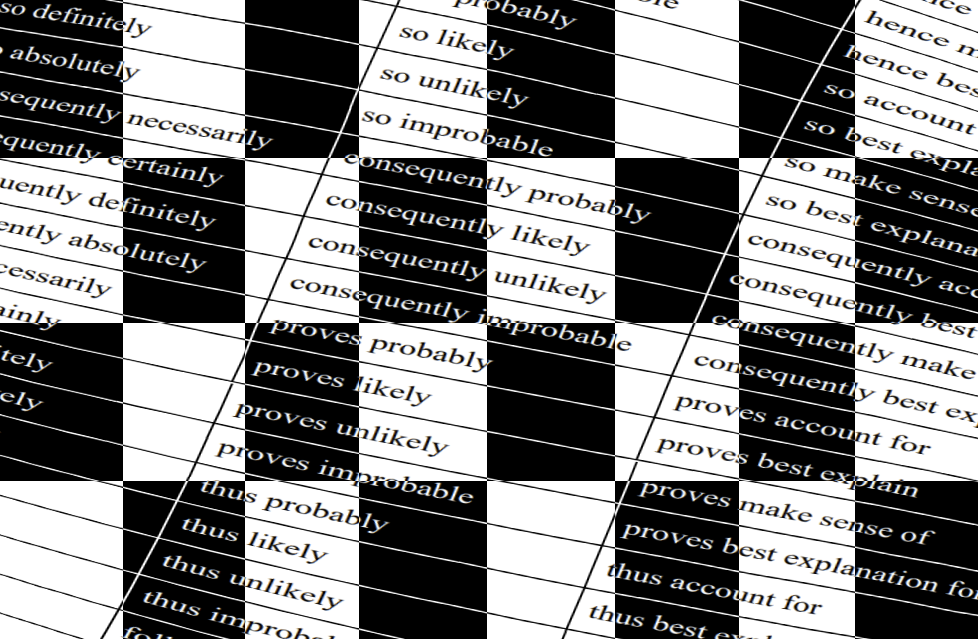

There is no statistically significant gender difference in the argument types used by frequently cited contemporary men and women philosophers in their articles, according to a new study that uses corpus linguistic analysis to search their works for “indicator pairs” of words that are likely to differentiate between deductive, inductive, and abductive arguments.

In “Philosophy’s Gender Gap and Argumentative Arena: An Empirical Study,” forthcoming in Synthese, Moti Mizrahi (Florida Institute of Technology) and Mike Dickinson (University of Illinois) look at the works of the 32 most-cited contemporary men and 32 most-cited contemporary women in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and conclude:

Our results suggest that both men and women philosophers make arguments in their published works. More specifically, our data reveal no statistically significant differences between the types of arguments advanced in published works written by male philosophers and the types of arguments advanced in published works written by women philosophers. In fact, both men and women philosophers make the three types of arguments we have searched for systematically, namely, deductive arguments, inductive arguments, and abductive arguments, with no statistically significant differences in the proportions of those arguments relative to each philosopher’s body of work.

Are the findings useful, as Mizrahi and Dickson think they are, for assessing a hypothesis about academic philosophy’s gender gap (floated by Marilyn Friedman, among others), that the mode of argumentation prevalent in philosophy, long dominated by men, deters or alienates women? Mizrahi and Dickinson explicitly acknowledge an objection that supports a negative answer to this question: that their sample of women is unrepresentative, owing to “survivor bias”:

we have selected women philosophers who have managed to be successful in academic philosophy in spite of the ‘logic-chopping’ and ‘paradox-mongering’ nature of argumentation in academic philosophy… There are plenty of other women who have fought in the ‘argumentative arena’ (Alcoff 2013) of academic philosophy as well but did not survive.

Still, they think their study can speak to the credibility of the hypothesis. Here’s the relevant (given their findings) part of their response:

If we were to find no significant differences in patterns of argumentation between the most cited male philosophers and the most cited women philosophers, then such findings could suggest that women philosophers can be just as concerned with arguments, and just as philosophically argumentative, as male philosophers supposedly are.

This won’t do. “That women philosophers can be just as concerned with arguments and just as philosophically argumentative” does not tell us whether the dominant modes of doing philosophy alienate or deter or make things more difficult for women in general. If we are looking for clues about what might be problematic with the status quo it is unclear why we’d focus exclusively on those for whom the status quo appears to be unproblematic.

That said, I don’t think this “concerned with arguments” hypothesis for the gender gap—understood as something that could be tested by counting the number of arguments people make and whether they are deductive, inductive, or abductive—is remotely plausible.

Further, it seems to be a misrepresentation of the complaints about philosophy it is supposed to capture. The complaints about philosophy that Mizrahi and Dickinson quote to motivate the hypothesis characterize philosophers not simply as people who argue, or argue a lot, or who use one type of argument more than others, but rather as people who are “just logic-choppers and paradox-mongers” and who are “concerned only with arguments.”

The complaint isn’t about the presence or degree of argumentation, but rather, it seems, about argumentation mainly detached from life as we know it, or detached from the contexts in which its problems arise. That said, I have no idea whether the “degree of detachment” of philosophical work varies by gender at all, or whether a hypothesis for philosophy’s gender gap that more faithfully represents this complaint of detachment has any evidence supporting it. Perhaps someone could figure out how to empirically test for these things.

And perhaps there is also interest in this: whether there are differences in how men and women argue about whether there are differences in how men and women argue.

There’s also the problem that selecting the 32 most cited men and women imports the citers’ biases into the study. It could be that the 32 most cited women are so cited because they argue the ‘right’ way — i.e. like men. To know whether there’s actually a difference, you’d have to look at all women philosophers, or at least a much bigger group, not just those who have been highly cited.

My first thought was to do something like look at all papers published in (say) Synthese in the last three years, and do the same coding of authors as female or male and of arguments as present or absent and deductive, inductive, or abductive. (Synthese would be a particularly good journal to consider since it has a large number of published papers every year.)

This of course would invite the same survivorship bias – maybe the *published* papers have the same types of arguments, but the difference arises at the level of papers that don’t get published?

(It might nevertheless be interesting to drop the gender angle, and just consider whether the pattern of argument types varies by journal, comparing Synthese to Phil Review to Ethics to the Review of Symbolic Logic or something. If the ratios aren’t different across these journals, or if they are in unexpected ways, that might reveal more about what these ratios actually mean.)

Yeah as you suggest, it doesn’t really solve the survivorship bias problem. If “hypotheses about the gender gap” here refers to putative explanations of the gender disparity in professors/PhDs/etc, then finding no existing variation in published work wouldn’t license inferences about selection into and out of the profession. Suppose you don’t find any differences in the broader sample. Then it’s still possible that women are choosing to not to enter or to exit philosophy for the reasons suggested

Yeah, or you could just train a classifier on this corpus and see which words and n-grams are most associated with which types of authors.

Would be easy to test in principle, I think. Just gotta find ppl to do the related studies and run the analysis, ha!

One thing to try I gues is to operationalize the explanation for the gender gap as variation among intro to econ (phil) class sections, TA sections, whatever

So just design the courses so that some profs/TA discuss issues with greater attention to context, less abstraction, however you want to cash that out. And then see how the different ways affect rates of dropping the class/continuing in the major, whatever

I haven’t read the paper, but isn’t there an equivocation on ‘argument’ here? As I understand the literature, most of the work on philosophy, argumentation, and gender is not focused on whether philosophy is ‘too deductive’ for women, but on the idea that the norms of argumentation in philosophy systematically place women at a disadvantage. So the point isn’t one about the form of arguments women offer, but about the norms that, in practice, govern philosophical discourse as practiced by mainstream analytic philosophers.

On another note, if it turns out that women *don’t* produce as many deductive arguments as men, that could be explained in terms of topic– I suspect women have out-published men in areas of philosophy that might lend themselves more to inductive arguments.

Don’t all oppressed groups use more autoethnographic/autobiographical methods? There are loads of examples. In “Africana Existentia,” Lewis Gordon writes, “It is no wonder that the autobiographical medium has dominated black modes of written expression. The autobiographical moment afforded a contradiction in racist reason: How could the black, who by definition was not fully human and hence without a point of view, produce a portrait of his or her point of view?” In “The Capacity Contract,” Stacy Simplican writes, “Because the vulnerability of the researcher is a crucial component in autoethnography, it counters abstract philosophical discussions of intellectual disability, as the latter implicitly disconnect philosophers from their own corporeality. In this way, autoethnography seems well suited for projects on disability, as both genres reject the disembodied and idealized subject.” In “What Can She Know?”, Lorraine Code writes writes, “Challenging the hegemony of prevalent methodological orthodoxies calls for imagination and a respect for autobiographical accounts and observations, even when those accounts appear to require reinterpretation.” Code criticizes “malestream” philosophy’s “characterizations of this abstract figure [of “autonomous man,” which] lend themselves to a starkness of interpretation that constrains moral deliberation while enlisting moral theories in support of oppressive social and political policies.” Those are just 3 offhand examples of autobiographical argumentation, which emerge from critiques of the traditional, abstract, “view from nowhere” epistemological method.

To my layman’s eyeballs, the gender/racial division in methodologies, insofar as it exists, is a defensive reaction to past discrimination in the field. When a Tuvel, Cofnas, Singer, what have you engaged with the subject matter of philosophy of race or gender using analytic methods, there’s outright hostility that they used their preferred methodology instead of these other modes of argumentation. When you call 911 and hide under the bed when a mid-level analytic comes around, claims about your methodologies strength ring hollow. Why not welcome the chance to show how misguided and harmful they are, if your tools are up to the job?

One more quick point – the authors say, “both men and women philosophers make the three types of arguments we have searched for systematically, namely, deductive arguments, inductive arguments, and abductive arguments…” That’s a very narrow range of styles to study. Michael Gilbert recognizes 3 additional modes of argumentation – the emotional, the visceral, and the kisceral – and Khameiel Al Tamimi recognizes a 4th mode – narrative/biographical argument. Gilbert and Al Tamimi say that these modes are utilized differently by different social groups. (Whether this is true in general, it certainly seems borne out in the philosophical literature, as per my previous examples). The results are inconclusive if only these 3 traditional modes are studied!

To be less misleading, “three” should replace “the” in the first sentence.

Gender is a fake and destructive social concept.

The correct view is gender nihilism or particularism, which are functionally equivalent. Everyone is their own thing, and even what they are varies from time to time. There is no gender. Gender is a socially destructive social construct we are obligated to reject right now. There are no men or women, period.

When someone complains to me about whether philosophy is better for men or women or exhibits gendered modes of expression, I regard that person as a backward knuckle-dragger who insists on putting people in artificial boxes. I laugh and then get back to serious business. Asking about whether men or women argue differently is the wrong question only backward people would ask.

This is so bizarre. “ then such findings could suggest that women philosophers can be just as concerned with arguments, and just as philosophically argumentative, as male philosophers supposedly are.” Why look for weird reasons for this gender gap when blatant sexism is right there in the open.

Ok so I haven’t clicked through and read the paper but based on these excerpts and summary this seems to take a poorly-motivated and implausible hypothesis (that women in academic philosophy argue differently from men), test it in a clearly flawed way (by examining the work of women and men who are highly-cited professional philosophers), and found that it appears not in fact to hold.

Nothing to see here would be my view.

Where is the logic in the hypothesis that who is different(Science can show you the differences, we can measure some of it ) must argue the same way?

Is it not correct to think that who is different must argue different?

Why are you so surprised IF the paper suggest that common logic applies to the question?

Of course different individuals can and do argue differently than each other, but I don’t see any reason to believe that women systemically argue differently than men… my experience is that if we were to make a distribution of people vs different argumentative styles, this would look much the same for everyone, just men, or just women.

So my priors on this hypothesis would be low. And I mistrust the intuitions that lead people to think otherwise.

“The complaint isn’t about the presence or degree of argumentation, but rather, it seems, about argumentation mainly detached from life as we know it, or detached from the contexts in which its problems arise.”

Maybe we haven’t found a way to test or verify this hypothesis. But we can already see that it may be unhelpful. It suggests, albeit somewhat indirectly, that women aren’t into PURE arguing, for its own sake; rather, unlike men, they need the further perk of some down-to-earth relevance. It’s like when we “sell” philosophy to our students by using pop-culture examples, because unlike people already sold on philosophy, already truly into it, they need the extra hook. Whatever its merit (fwiw I don’t believe the hypothesis, and I totally get that you weren’t defending it), this is the kind of idea that may serve to reinforce, rather than help remedy, the underrpresentation of women in philosophy.

I’ve looked at the paper. It’s a sad bit of work. In real-world data analysis pov, it’s the wrong way round. If you have a tool – word category frequency – you should apply that blindly to a random sample of articles, look to see if it clusters anything significantly and what is left out. Then you can test your clusters against all factors e.g. with a multivariat analysis (how much of this clustering is accounted for by e.g. gender, publication date, country of origin, etc. etc.) double blindly (i.e. the statistician should be given categories A, B, C with someone else knowing how those related to facts). Once that’s done with random articles, it would be legitimate to re-apply the whole method (blindly) to the hand picked list to see if there’s a significant difference between those and the random papers.

And that’s even before the issue of bias setup by the system and the source…