Women in Philosophy: Recent Reports (updated)

Two studies have recently been conducted on the status of women in the philosophy profession, with one published by the British Philosophical Association (BPA) and the Society For Women In Philosophy (SWIP), and the other described in a post at the Canadian Philosophical Association (CPA) site.

[Jenny Saville, “Arcadia” (detail)]

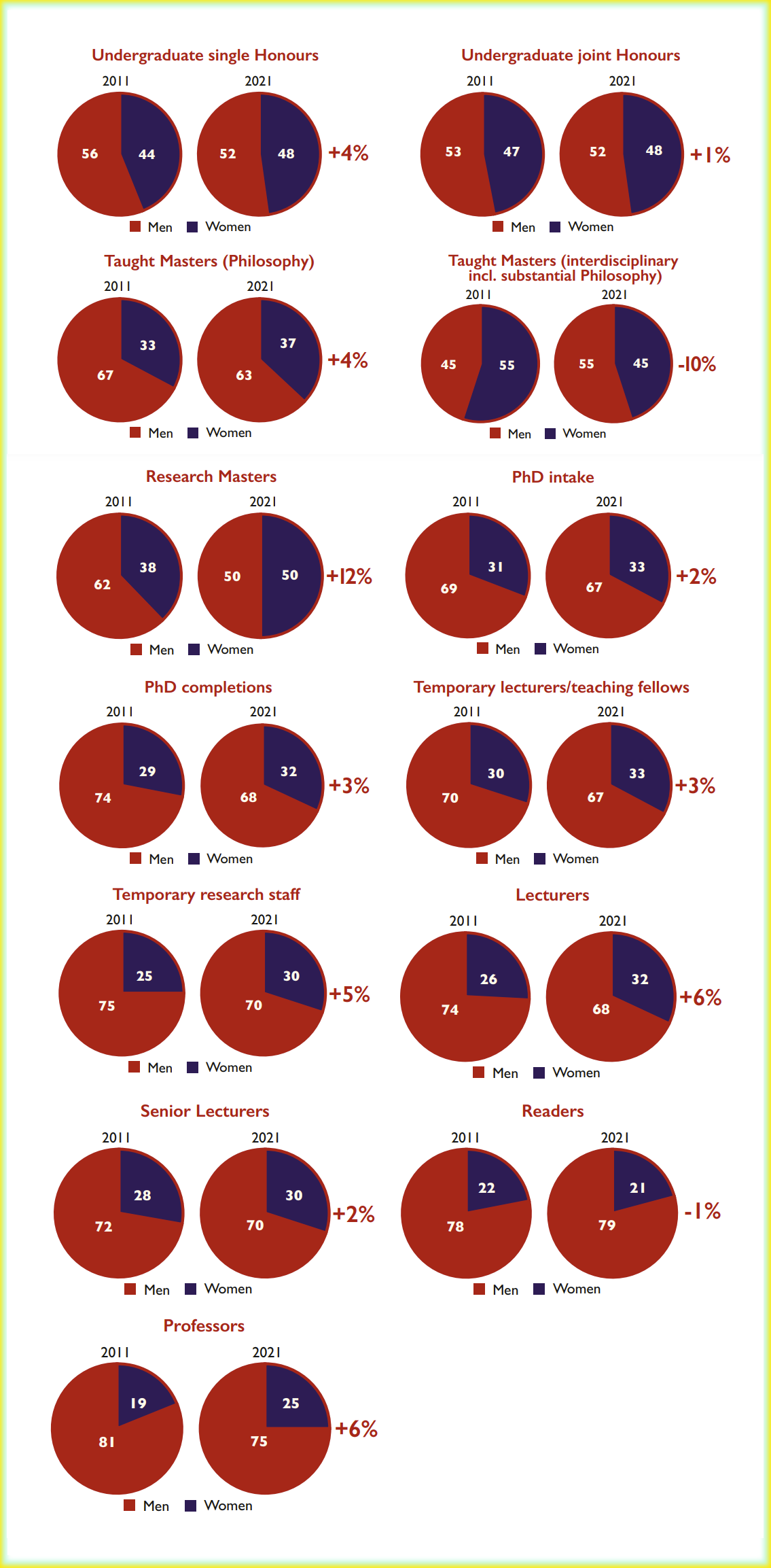

Some of the information is the result of new survey data that reveals what’s different in 2021, compared to 2011:

from “Women in Philosophy in the UK”, 2021, by Helen Beebee & Jennifer Saul

-

- The new survey results paint a picture of slight improvement in representation of women at nearly all levels, with substantial improvement in the percentage of permanent staff who are women (up from 24% to 30%) and in the percentage of professors who are women, (up from 19% to 25%).

- Nonetheless, there is clearly still much to do: women continue to enrol on philosophy courses in numbers very close to men (48%, up from 44% in 2011), but they continue to leave the field starting at MA level and then yet more at PhD level. The drop-off between undergraduate and PhD remains unchanged at 15 percentage points.

- Overall, the figures suggest it would be well worth focusing attention particularly (though obviously not exclusively) on ways that undergraduate and postgraduate experiences for women can be improved.

Perhaps the most significant change since the 2011 Women in Philosophy report has been the explosion of research attention devoted to the issue of the underrepresentation of women in philosophy. While the underrepresentation of women in academia was already well studied, especially in STEM, in 2011 there had been virtually no empirical research relating to women in philosophy. There has now been a huge amount of work in this area. The 2021 report describes 3 particular topics of research in detail:

-

- empirical studies of undergraduate student enrolments in philosophy degrees

- studies of implicit biases generally, and of their influence on and within philosophy

- work on intersectional oppression in philosophy

The last ten years have seen a flourishing of interventions aimed at improving the situation for women and other marginalised groups in philosophy, including actions related to:

-

- sexual harassment in academia

- diversity in the curriculum

- Athena SWAN

- The BPA / SWIP Good Practice Scheme

- The GPS impact report (2018) written as a result of a small-scale survey of departments subscribing to the scheme revealed the two biggest impacts to be culture change—primarily relating to a less hostile and more constructive atmosphere in seminars and workshops—and a higher proportion of female speakers at research events.

-

- parental leave funding for PhD students and early career researchers / temporary contracts

- precarious employment particularly effects women, first generation students, people of colour, disabled people and caregivers

- the gender pay gap isn’t closing very quickly

- the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing gender inequalities

You can read the full report here.

The report posted by the CPA, “Gender Ratio in Philosophy: An Inferential-Statistical Model of Possible Determinants,” takes up the question, “Why are only about one third of academic philosophers women?” Katharina Nieswandt (Concordia), who is leading a team of philosophers and psychologists researching this, writes:

The Question: Why are only about one third of academic philosophers women?

Answer: Mainly because only about one third of students who either enroll in the undergraduate major or stay after introductory classes are women. I.e., at least in North America, the main pipeline leak occurs at the first stage of a potential academic career. Retention within the university system thereafter is probably proportionate, except for a significant drop at the step from associate to full professor…

Follow-Up Question: Why, then, do women either not enroll in the first place or drop out after the introduction? I.e., why is philosophy not an attractive major to women?

Answer: From a review of theoretical and empirical work on gender gaps in academia, we designed and implemented a survey…. The two most important factors turned out to be self-perceptions of brilliance and of belonging….

Overall, our findings provide (of course defeasible) evidence for the claim that students choose philosophy because they perceive a good fit between philosophy, qua requiring brilliance, and themselves, qua being brilliant, combative, systematizing, and indifferent towards “worldly rewards,” like family-life and money…. Fewer women than men show these self-perceptions and preferences.

[updated to add:] According to Professor Nieswandt, “this is the first inferential-statistical model, and in fact one of the few studies on the whole topic of women in philosophy to provide any inferential statistics at all.”You can learn more details about this work here.

One of the arguments for hiring a non-white non-male for a college or university teaching position instead of a white male, all other relevant things being equal, is that the non-white non-male’s non-whiteness and non-maleness will show other non-white non-males that they can be non-white and non-male and yet do philosophy. The idea seems to be that it will help to diversify the profession if non-white non-male students can see themselves in their professors, and a good way for non-white non-males to see themselves in their professors is for the professors to be non-white or non-male.

So, if the claim above is true (that there’s a perception of philosophers as unconcerned with family or worldly goods), it might put some pressure on this argument. That is, it might be (1) that what women would tend to prefer to see in a philosophy professor is not so much womanhood as a person (not necessarily a woman) who’s not indifferent toward family or worldly goods. That is, whether the professor is a woman might be less important than whether the professor appears indifferent to family or worldly goods.

That said, however, it might also be (2) that what women tend to prefer to see in a philosophy professor is a *woman* who’s not indifferent toward family or worldly goods. This, I think, doesn’t put the pressure on the argument that 1 does.

It doesn’t depend on preference, right? It depends on what’s most likely to get them “to see themselves” in those who fail to be indifferent. If seeing a woman is the crucial mechanism, the evidence reported puts little (if any) pressure on the argument mentioned for hiring non-white non-males.

That’s a good point.

Perhaps I should add: I’m not convinced that representation matters. I’m much more inclined to believe that what matters is that brilliant non-white non-males be recruited at higher rates than mediocre white men (who, because of their mediocrity, have trouble identifying brilliance in men and in women).

Hi, Jen. Yah, I’m not convinced by the representation argument, either. So I’m with you there. (I think that’s what you’re referring to — correct me if I’m wrong.) I was just exploring how the claims reported in the post might make contact with one of the usual arguments for identity-conscious hiring.

There’s already a word for a non-male, and that word is “female.”

That’s certainly what I think! I was just trying to avoid ruling out conceptions I don’t happen to share.

No worries. I know you weren’t doing this intentionally, but referring to females as “non-males” can (unintentionally) send the signal that males are the default. To quote Simone de Beauvoir, “Thus humanity is male and man defines woman not in herself but as relative to him; she is not regarded as an autonomous being.”

I think it might make sense to describe an Intersex person as non-male yet not make sense to describe them as female.

Men in philosophy don’t have families or worldly goods?

Male philosophers seem somewhat more likely to have families than female philosophers. I don’t have the data on philosophy and perhaps it is a bit better than science but I suspect not by much.

“The women who do make it often do so alone. Women professors have higher divorce rates, lower marriage rates, and fewer children than male professors. Among tenured faculty, 70 percent of men are married with children compared with 44 percent of women.”

https://slate.com/human-interest/2013/06/female-academics-pay-a-heavy-baby-penalty.html

I appear to be replying to the comment immediate above.

I am commenting on the post. Apologies.

BTW per the Slate article above–women also make less money.

“Men and women retire at about the same age, but women have less income to rely upon in retirement; their salaries at retirement are, on average, 29 percent lower. This is partly the result of parenting responsibilities: For women, each child reduces her pay. This is mostly as a cumulative effect from time and money lost earlier. But children have no such effect on men’s salaries.”

The article says that 70% of academic men become fathers. 61% of US men are fathers overall.

Assuming philosophers are similar to other academics a man may come out well in an academic career if he happens to want children.

According to Statista around 52% of women in the US have children. but only 44% of academic women have children. Philosophy may decrease your odds of having children if you’re a woman.

Being a woman means a hit in retirement income. Men who are fathers do not suffer a decrease in retirement income.

When women consider the odds of obtaining family and worldly goods they face different odds.

The higher number of men choosing philosophy does not seem to indicate less regard for family and worldly goods but instead a much greater likelihood of getting them.

It’s interesting that nobody seems to be concerned with increasing the ratio of males in psychology.

It’s not especially surprising that a philosophy blog focuses on issues in philosophy rather than other subjects.

Might there not be a relationship, though? Imagine that men find fields with a supermajority* of women less attractive than fields without; and imagine that women find fields with a supermajority of men less attractive than fields without. If that were true, then the fact that some fields have a supermajority of women could help to explain why philosophy has a supermajority of men.

FWIW, according to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences (https://www.amacad.org/humanities-indicators/higher-education/gender-distribution-advanced-degrees-humanities), the gender breakdown of advanced degrees awarded is as follows as of 2015 (my percentages based on looking at graph II-26a):

Education: 75% female

Health & Medical Sciences: 72% female

Behavioral & Social Sciences: 64% female

Humanities: 61% female

*–I’m using this term as a shorthand for “much greater presence of one sex over another”, and not necessarily as a particular percentage.

Are you suggesting that given the possibility of a relationship, it’s surprising that philosophy blogs and philosophers aren’t focusing on the issue in psychology? Why would it be surprising if there is no evidence to suggest the relationship is more than a mere possibility? Or are you suggesting there is evidence?

“Are you suggesting that given the possibility of a relationship, it’s surprising that philosophy blogs and philosophers aren’t focusing on the issue in psychology?”

No.

“Why would it be surprising if there is no evidence to suggest the relationship is more than a mere possibility?”

I wasn’t suggesting it was surprising.

“Or are you suggesting there is evidence?”

No, I’m not suggesting there is evidence. I’m suggesting that there’s a possible relationship there. There’s no evidence for it that I’m aware of. I do think there may be a relationship there, and I think the question should be studied by someone to find that out.

Then why reply to David Wallace’s comment in suggesting this? Bizarre.

When we consider the reasons for the ratio of males to females in philosophy, it only makes sense to consider why we are better at attracting males than other departments. The number of men we get is not going to be independent of other departments’ abilities to attract men.

I get that, but the number of men we attract and retain also won’t be independent of the military’s ability to attract and retain men. What’s your point? We should be surprised only if we have evidence of a relationship that stands a good chance of throwing light on philosophy’s issue.

We are not, in general, losing female majors to the military. We are, in general, losing them to other majors. Likewise, the men we get are generally choosing between us and other majors rather than between majoring in philosophy and joining the military.

I get that there’s this difference between the military and other majors. (I used the example of the military precisely because of the *prima facie* importance of this difference.) You still haven’t identified something about the psychology issue that makes it likely to throw light on our issue.

Anyway, I agree that when looking for an explanation of the philosophy issue, we should be interested in the subset of people in college and the subset of their interests, beliefs, etc. that bear on their choices for a major. The question is: what is it about the psychological profiles (i.e. interests, beliefs, etc. that bear upon their choice) of psychology majors that makes them *likely* to throw light on our issue? What makes them more likely to do it than, say, the profiles of math majors (or biology, sociology, political science, history, and art majors for that matter)? It is not enough, I take it, to respond that ratio of men to women in psychology is similarly skewed. For this isn’t enough to make it *likely*. I suppose our disagreement might simply come down to a difference in intuition regarding the likelihood.

Psychology and other disciplines are relevant because their attractiveness to male and female students looking for majors will be a factor in how many male and female students major with us.

You mean nobody seems to be doing this kind of thing? https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-33/september-2020/tackling-gender-imbalance-psychology

Psych departments do care. Maybe we’ll see attempts to make that discipline more combative. Fingers crossed.

Maybe they should go back to their roots: cocaine.

I’d be interested to see how the above explanation being given for the underrepresentation of women might also generalize to Hispanics or Latinos. It seems to me that some of them might have similar concerns given that said groups tend to value family life strongly for cultural reasons and that there is ample empirical evidence supporting this.

So I suppose I am wondering whether, like women, both male and female Hispanics’ familial values, stemming from their culture, deters them from continuing in philosophy for the same reason as women (at least when it comes to family life). Is there any data confirming this?

Speaking anecdotally, as a former Hispanic undergrad who chose not to pursue grad school (but could have), I can say that the prospect of spending 6-10 years in grad school did not entice me precisely because it would make it far too difficult for me to start a family. That coupled with the well-known fact that, even if I did get a permanent academic job after grad school, that it would probably be in a state far away from my extended family was an absolute dealbreaker.

The fact that psychology and philosophy are mirror images of one another in male/female involvement is very interesting, and rarely gets the attention it seems to deserve. Presumably, what is reasonable to do in one case is reasonable to do in the other.

I wonder which of these options people prefer:

Option 1: Radical Mechanical Correction. This one is very simple. If we combine the male and female philosophers and psychologists, we have plenty for a fair distribution in both disciplines. All we need to do is implement strict limitations in those departments on both levels. Let’s suppose that, at a given university, there are 300 philosophy majors and 300 psychology majors. Well, we limit the number of male or female psychology majors to exactly 150 (or a bit lower, to make room for people who self-identify as non-binary). We put similar limits in place for every single course in the departments (especially introductory-level ones), for graduate program admissions (the department gets no funding for its graduate program unless it makes the ratio of male to female students exactly 1), and hiring. A male or female professor leaves? Hire another one of the same sex immediately, or terminate the employment of one of the opposite sex, etc. This option rides roughshod over departmental freedom and the personal autonomy of students, but it guarantees male-female equality very easily.

Option 2: Address Departmental and Disciplinary Bias. Assume that all disparities must be products of discrimination in the department or discipline, and take steps to remove that discrimination. Steps have already been underway for some time to deal with this on the philosophy side. To do the same in psychology, one could organize males in psychology at all levels to supply a perspective on how the psychology department continues to alienate male students. The recommendations of committees of males in psychology should be implemented until male/female equality is achieved. These committees could suggest ways to ‘masculinize’ the curriculum after identifying whatever it is that makes male students check out. If that means that psychology has to become radically transformed in the process, so be it. Of course, the same should be done in philosophy, with male and female reversed.

Option 3: Focus on Pre-College Bias. According to the Canadian research Justin W. presents, there is strong evidence that the male/female disparities we observe in philosophy are primarily the effect of much earlier preferences that affect the course and major choices of incoming male and female students. If that is true, Options 1 and 2 focus on downstream effects without ever having a chance of getting to the source of the issue. Instead, the problem should be addressed by conditioning pre-college children and teens, possibly from a very young age, so that the preferences of college-age males and females for philosophy or psychology are exactly the same.

Option 4: The ‘No Problem’ Approach. Perhaps, rather than trying to socially engineer a result of equal representation in all disciplines, we should simply accept that preferences and autonomous career choices are unevenly spread across the sexes. On this option, care should be taken to make things pleasant for people in both disciplines, and things that make a department or discipline uncomfortable to those who prefer it (like sexual harassers or people who make bigoted general comments about the underrepresented sex) should be dealt with. Beyond that, if people are happy with the major they choose, Option 4 doesn’t see a problem to solve.

*

What I often find in these discussions is that everyone gets started on the assumption that one of these options is the right one, and from that point on it’s all a matter of working out what’s best given that option. But it seems to me that the choice of which option to pursue is a reasonable and important first step.

The piece linked by Helen Beebee demonstrates that philosophy and psychology are not mirror images in at least one important sense: only 20% of (UK) psychology undergraduates are male, but 37% of psychology lecturers (read: junior academics) are male, and fully 67% of psychology professors (read: full professors, roughly) are male. I found that striking.

That *is* very interesting, David. Among other things, it casts some doubt on one hypothesis for the disparity in philosophy: that women are generally uninterested in pursuing disciplines whose professors are mostly male.

I’m sure that many women who are disabled, racialized, and in other marginalized groups in philosophy will recognize the problems with the analysis of this post as well as with the analyses of the various studies highlighted in it.

It would be interesting to see breakdown by area. If the 2009 philpapers survey is any guide, there are big differences in percentage of females in different areas (I wasn’t able to find data on this in the 2020 survey). For example, looking at areas that had more than 50 respondents, 5.3% and 8.3% are female in philosophy of physics and in logic, while 22.6% and 23.9% are female in philosophy of cognitive science and in social/political philosophy. This resembles patterns in related academic fields: less female representation in fields such as math and physics, and more in psychology and other social sciences. If this data is accurate, it suggests that the problem of female underrepresentation is not a problem of philosophy as such but has more to do with specific subject matters.

I wasn’t able to add the link to the data for some reason, but it can be found on the 2009 philpapers survey page.

I really appreciate all the work that the BPA puts into these valuable reports. But I think they missed one of the most important studies on this topic, previously discussed on Daily Nous and available here:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/hypa.12443

These authors found in Greece, there is no female gender gap at the undergraduate level (in fact it was 70% women) and this seems to largely be attributable to Philosophy being a high school subject. The authors put a lot of weight on this having an effect on pre-university stereotypes and climate, but a large component is that it also means majoring in philosophy leads to certain job opportunities, namely, being able to teach high school philosophy (job availability also seems to explain why Mathematics has a much lower undergraduate gender gap than other STEM fields; see my paper below). This is notable for two reasons: 1) it suggests that desirable career opportunities can easily overcome many of the purported undergraduate climate factors thought to be contributing to gender gaps in other countries, and 2) it suggests that many of the purported undergraduate/classroom climate factors are not what explains faculty gender gaps, given these classes were overwhelmingly women but the faculty gender gap is comparable to that of other countries. (One might suggest that faculty-level climate and bias might still be an issue. Assuming bias has a somewhat proportionate effect on gender gap, I would note that this would require Greek faculty to be both significantly more biased than other countries since there’s a much larger pool of female candidates to dissuade, but also not so biased as to make the gender gap any larger than other countries. This strikes me as somewhat unlikely).

More generally, I think this literature needs to start emphasising effect size more than just statistical significance. I realise this isn’t always possible, but we don’t want to fall prey to the streetlight effect, searching for our keys under the streetlight just because this was the easiest place to look. It’s possible to have 100 studies showing e.g. stereotypes or implicit bias have some statistically significant effect and yet it be the case that completely eliminating such factors has negligible effect on the actual gap size. This is one of the reasons why I wrote a paper reviewing which interventions aimed at closing gender gaps in STEM fields have actually had some success, and which might be relevant to philosophy, and which I think many people interested in this area might find useful:

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/ergo/12405314.0006.026?view=text;rgn=main

In summary, evidence suggests role models have some effect (but it needs to be one students can identify with, being of the same sex alone may not be enough), belonging matters (but can be achieved by having students do tasks which reframe their interactions with others) and jobs probably make a big difference. (I suggested that improving undergraduate gaps would have flow-on effects at higher levels due to improving e.g. undergraduate classroom climate; the earlier paper suggests I was mistaken).

I also think this literature needs to take more seriously the risk of survivorship bias when considering methodology. All of the papers which look at the experiences of women in philosophy, or which only look at data using philosophers, are looking at the women who ‘survived’ and then effectively asking them what almost prevented them from surviving. But this can be like asking planes returning from war where they got shot to determine – given the aim of increasing the number of planes returning – which areas of said planes most need more armour (this actually happened). Counterintuitively, you need to put more armour in the areas where the returning planes *don’t* get shot, which would be (roughly) equivalent to seeing what women in philosophy find easier relative to women who did not go into philosophy (of which the point about worldly rewards etc. would fit). Given most of the gap develops before majoring, this will mean looking at women who did not major at all.

“The ‘pre-university effect’ is, however, somewhat puzzling from a UK perspective, where most students choose their major before arriving at university and—outside Scotland—have limited opportunities to switch once they start, and we have seen close to gender parity in these numbers for some time. There is a drop-off in the UK between undergraduate and Masters levels (from 48% to 40% in 2021). But this cannot be explained, even in part, by a pre-university effect, given that female undergraduates in the UK have all already actively chosen to major in philosophy.”

This seems to be like arguing that since a sample of heterosexual couples start out by doing equal amounts of housework, when the males end up doing less housework several years into the relationship (perhaps after a child is born and the housework demands increase), the cause of this housework gap could not have been factors occurring prior to the two people forming a couple – after all, the males had actively chosen to do equal amounts. I take it we would rightly emphasise a lot of things that occur before the couple forms in explaining this persistent gender gap.

Thanks for the links, Adam — will check those out! Just on the pre-university effect: the hypothesis we’re referring to (as defined by Baron, Dougherty & Miller) is the specific hypothesis that there are “causes that increase female under-representation among prospective students who intend to major in philosophy, even before they have begun university” (BDM, 332). So if the pre-uni hypothesis is true, the drop between intro course and major is explained simply by the female students sticking with a decision they’d already made before they started, as opposed to them being disproportionately *put off* majoring in philosophy by what happens after they arrive at uni. That distinction, and hence the pre-uni effect hypothesis thus defined, doesn’t apply in the UK (outside Scotland anyway). And what’s puzzling is why, if the pre-uni effect hypothesis is true in Australia (where the BDM study was done), and hence prospective philosophy students *there* are disproportionately male, they aren’t disproportionately male in the UK. (One possibility I hadn’t thought of is that this connects with the extent to which philosophy is taught at high school, as per your previous post.) So anyway the claim wasn’t that the big drop-off at Masters level in the UK can’t be explained by anything that went on before the students started their undergrad degrees!

Thanks Helen, apologies if I’m still misreading something, but is idea is that: in Australia BDM hypothesise that females already have less intention to major, and so the increase in the gap from Day 1 enrolments to majoring is mostly attrition of people who didn’t intend to major. But since in the UK females are already intending to major roughly at parity, this hypothesis (which is about things leading up to the intention to major prior to university) cannot be true, so the puzzle is: if BDM are correct, why don’t we observe such effects causing the attrition to happen earlier, resulting in our UK group of people who ‘intend to major’ being mostly male?

I had been thinking of ‘intention to major’ as a scalar, psychological property, in contrast to ‘declaration of an intention to major’ which is binary and what I took the UK data to be directly measuring. And supposing that all that is needed for someone to declare an intention to major is that they have (say) >51% intention to major in that area, it would still be the case that in the UK you start out with gender differences in intention to major that are similar to that of Australia, even if the UK group of ‘declared intention to major’ is at parity, and this locks you into actually majoring even if your intention decreases. There could then be things which happen after Day 1 which reduce intention to major across both sexes, but I had taken pre-university effects to include things which might have interaction effects with such factors e.g. suppose in their third year students learn that being a philosophy major is uncool, and male would-be majors are less concerned with being cool (perhaps they are already uncool and can’t go any lower) due to pre-university factors. One framing of this is that females are being put off by something happening after they enrol, and so we need to make philosophy cool, but another is that what explains the decrease is propensity to care about coolness, which I had been considering a pre-university effect affecting intention to major.

What happened to stereotype threat (between 2011 and 2021)?

It turned out not to replicate very well, if at all.

I vaguely remember that years ago some philosophers warned (unsuccessfully) that stereotype threat was uncritically accepted as an important part of the explanation of gender disparity in our field.

Perhaps Neven is referring to “Women in Philosophy: Problems with the Discrimination Hypothesis.”

I can confess to being uncritical here. At the time, I was not as aware of the statistical issues that have led to the replication crisis. FWIW, experimental philosophers have been doing a pretty good job of improving practice and methods in the last six years or so.

The notion that “there’s much work to do” suggests that those women who choose to leave the field, or many of them at least, are making the wrong decision, does it not? Maybe the men who disproportionately stay in the field are the ones making the mistake, or maybe they are equally good life choices. I’m not sure I see a problem here that needs solving.

No, it does not suggest that those who leave make the wrong decision. To leave is not necessarily to choose or decide to leave, for one can leave by force. It simply suggests that the rate at which women leave philosophy is undesirable.

You are now free to say you’re not sure you see why it’s undesirable, which is a perfectly reasonable thing to say if true. However, if it’s true, you likely lack imagination, experience, or good judgment. For your sake, I hope it’s experience.

“However, if it’s true, you likely lack imagination, experience, or good judgment. For your sake, I hope it’s experience.”

If what I say is *true*, then I am presumably flawed in one of these ways? How? And why the need for the personal attack?

“If what I say is *true*, then I am presumably flawed in one of these ways? How?”

Well, do you know what desirability is? How it is to be explained? If not, that’s due to a lack of philosophical experience, and not only could it explain why what you say is true, but it would explain why you’re flawed in one of the mentioned ways.

“And why the need for the personal attack?”

It’s not a personal attack. It’s just to let you know where you likely have room for improvement. We always have room. Some have more than others. It’s good to exhibit humility, and I’m helping you recognize your need for it. I’ve done the same with others, some of them are in this discussion.

Indeed, it’s good to exhibit humility.

The discussion of Katharina Nieswandt and her co-authors is a great evidence-based approach to the issue. The “striking results” include the following:

The key variables are characterized as follows:

If I’m reading this right, then an interest in a systematic rather than an empathetic career, a perception of oneself as combative, and a willingness to place less significance on money and family, correlates with a sense of belonging in philosophy rather than psychology.

It seems that one question worth pursuing is whether philosophy is, at least as it’s practiced today, one that rewards systematicity and combativeness over empathy, and which tends to inhibit the ability (relative to psychology) to earn as much money and start a family. If it does, then one possible explanation for why there are more women majors in psychology rather than philosophy is that women tend to have a set of preferences, and a set of true beliefs about philosophy and psychology, that make it reasonable (given those preferences) to tend to opt for the latter over the former.

Prima facie, this interest in empathy over systematicity, and the over-representation of women in disciplines like education, healthcare, and behavioral and social science, and the overrepresentation of men in disciplines like physics, math, and engineering, fits well with the “men prefer to work with things, women prefer to work with people” hypothesis in social science research on gender differences in occupational choice.

Of course, even if it were found that philosophy and psychology as a matter of fact line up with these preferences, this doesn’t touch the normative question of whether philosophy as a profession should prioritize combativeness and systematicity, or be such that financial gain and family are less likely than in psychology. But it seems worth considering whether the differences in representation of women and men in philosophy and psychology today are at least partly the result of a combination of preference and true belief.

Anyway, I hope I haven’t misread or -interpreted anything here, so please correct me if I’m made a mistake somewhere. Plenty of work to do going forward, and thanks to everyone for giving this the attention it deserves.

I don’t see how we can look for the reasons for the ratio of males to females in philosophy without also looking for the reasons for the ratio of males to females in other disciplines, including the ones that attract more females than males. After all, if we lose a major, it’s generally because they have been attracted away by another major. How attractive other disciplines are to males and females will impact the ratio of males and females that end up in philosophy.

But isn’t the whole idea that all majors should be equally attractive to all genders (and so that there are no preferences for subjects that are inherently gender-based only) and that this should result in people lining up for university studies and majors within them in the precise ratio in which they exist in the population at large and if this is not the case, then we need to keep correcting things until we have the desired outcome?

Is that not compatible with what I said?

Two thought experiments and a follow-up question:

I’m genuinely trying to understand the motivation. Answers are welcome.

In both cases, it depends. For the movie case, suppose: (1) The lives of people who enjoy the movies are significantly improved by the value of the movies, and no comparable improvement would likely otherwise occur. (2) The movies have content which tends to perpetuate the preferences that lead people to dislike the movies. (3) The relevant content can be removed without a significant loss of the value of the movies. For these reasons, the content might be objectionable enough that the movies should be changed to remove the content.

For the music case, suppose the preferences that make people enjoy the music significantly improve the lives of people who have them, and no comparable improvement would likely otherwise occur. This is enough to make pressing the button an improvement.

I think this reply is complete only if we carry the movie analogy fully over to philosophy. But when we do I think conditions (1)-(3) are not obviously satisfied, and so Justin Kalef’s question remains open.

For instance, I find both claims in (1) pretty strong. Starting with the first, I think it is doubtful that, as a rule, philosophy would significantly improve the lives of most who would study it. One reason is that philosophy is notoriously inconclusive, and this leads many smart people to other disciplines whose methods and results more reliably yield consensus. Another reason is that I do not think we can isolate the benefits of studying philosophy from the sociological context in which this study occurs. But many studying philosophy struggle with mental health because they are precarious, do not study something that garners much social respect, and are very worried about whether and how to translate their expensive education into future earnings to pay for a basic, comfortable life.

If by ‘improve the lives of…’ you are instead focusing on the instrumental benefits of studying philosophy, however, then now the second, subjunctive claim in (1) is problematic. For even if we allow that in this particular way philosophy improves the lives of those who study it, I see no reason to believe it would uniquely do this. A solid math degree demands one be able think just as rigorously and clearly.

As for (2) and (3), following up on Prof L’s query, I think that for your objection to go through it is not enough to observe that, in the case of movies, it is conceivable that some offending content could be removed and that this would not damage the movies as such. If the analogy to philosophy obtains, then I think you owe an account of (a) what this offending content in philosophy might be, and (b) why and how it can be removed without damaging the discipline. Otherwise it’s just not clear your reply to Justin Kalef carries over to philosophy, which was the thrust of his questions.

Thanks for replying. This is interesting. But unlike you, I don’t think that the reply is complete only if… My reply to Prof L makes clear what I’m up to in the comment. And it is complete as is.

Of course, it’s perfectly reasonable to ask how a similar response can be offered for the case of philosophy. In the spirit of answering that question, I’ll refer you to my reply to one of his comments below. When you read it, I hope it becomes clear why your first worry about whether (1) carries over to philosophy misses its mark, for the claim need not be that all or even most of those who study philosophy are the benefactors. (The analogy need not be perfect. It does need to be reasonably clear, and I think it is.)

Your worry about the subjunctive clause of (1), too, misses. The reason is that the benefactors I have in mind are those whose philosophical study is not simply instrumental to their living a fulfilling life, for such a life (as I’m imagining it) is one that integrally involves philosophical inquiry at the highest level. For these people, studying mathematics is not enough (unless, of course, it is the philosophical study of it at the highest level).

Your worry that builds on Prof L’s thought misses as well. The analogy (since it need not be prefect) doesn’t require that *content* of philosophy be removed or changed, just that something about studying philosophy be changed. This can be something as simple as changing the culture within departments.

Thanks for the exchange. I hope my responses, although brief, were somewhat satisfying.

I’m not sure if this addresses your questions about motivation, but suppose that there is a history of people not letting women watch action adventure movies, and some evidence of this continuing. Suppose also there’s a history of people being discouraged from liking a certain kind of music based on their gender or sex, etc. Does that matter? Because I suspect that may be where you differ from some of the defenders of having greater participation by females in philosophy. They’re worried – more than you, I guess – that women have been pushed away from philosophy for bad reasons. If there were no such history – with its (arguably) still continuing effects, then maybe your thought experiments would be relevant. But also what Jen says here.

Thanks, Chris.

“[S]uppose that there is a history of people not letting women watch action adventure movies, and some evidence of this continuing.”

Is the idea that women are significantly underrepresented in philosophy because men haven’t let women study it, and many women are not allowed by men to study philosophy today?

I for one would find that quite surprising. I’m 50 years old, and none of the many female students I knew in my undergraduate years (or before) were allowed or forbidden by men to study different academic subjects. Moreover, I’ve also been good friends with a number of people a generation older than I am. Feminism famously prospered on university campuses throughout the 1970s. If any man had dared to presumed to ‘let’ female students study one thing rather than another, I’m pretty sure many of them (including women from that time whom I know personally) would have done more than pay them no heed: they would have protested the very idea of men giving women permission to study whatever they want, and would probably have been more apt to study those things just to spite the men who would dare to suggest such a thing.

Those women would be about 70 years old now. I just don’t see how it can be plausible that the high male-female ratio in philosophy today, half a century later, can be a function of men not giving women permission to study whatever they want, and of women caring enough about this to passively obey.

Slightly over half the students in law school and medical school today are women. The fact that the legal and medical professions were dominated by men a few decades ago hasn’t stopped women from enrolling in these schools in high numbers, and thriving in them. If the ‘men historically never let them’ rationale is so effective in philosophy, why has it been so ineffective in so many other fields?

The hypothesis that men and women are not equally interested in all subjects, and that philosophy is a field in which proportionally fewer women are interested (just as psychology and many others have proportionally fewer male students) seems much more plausible to me.

This thought experiment overlooks the existence of hybridized movies like The Princess Bride. It’s got romance, comedy, action, drama. It has Cary Iwves who was and is so handsome and charming.

In reality, philosophy is quite big in terms of its “sub-genres” nowadays. You don’t have to change much of the character of philosophy itself to attract students, but rather, direct students towards its various and different avenues.

When I was a science major a lot of my science teachers informed us about the many specializations one can pursue. Likewise, I think philosophers should tell their students about the various things they can pursue in philosophy that have not been offered at their university.

To give an example, my university did not have any epistemology class. I was briefly introduced to it in my feminist philosophy class when we went over stand-point epistemology. My teacher was like, “…and that’s epistemology a branch of philosophy dealing with knowledge.” And I was hooked and wanted to learn more.

However, as somebody who is first generation from lower class background, going to grad school in philosophy is risky so I opted out.

The purpose of the examples he uses is simply to put pressure on the idea that disproportionate representation between groups due to disproportionate preference-distribution between those groups is itself to be avoided. So his example of movies can be modified to avoid the worry you raise. He’ll just advise you to imagine away the problematic “hybrid” movies. It’s a fair move.

What he apparently fails to understand is that his opponents are not all näive or simple-minded in opposing the underrepresentation of women and POCs in philosophy, and that they are not all foolishly guided by the simple idea mentioned above.

Yeah I agree. If we had to make a list of possible/probable reasons as to why women are underrepresented, it would be long than being reduced to simple personality differences between men and women.

I do think some of the surveys and pollings could be better and more descriptive if the researchers asked more direct questions like: “Will you be applying to graduate school for philosophy? Why or why not?”

And give a list of rationales or have them write their own if theirs are not included.

Oh dear… the good old ‘he fails to understand that…’ rhetorical move that I try to get my freshmen to stop using. If you’ve got a serious move to make within the dialectic, I’d be interested in hearing it. But no thank you to that.

If you don’t believe that your examples actually pose a problem for opposition to the underrepresentation of women in philosophy, then what is the point of the comment? You do believe it, so you *apparently* fail to understand…

I already provided grounds to dismiss the purported problem you attempted to pose. Contrary to what you believed when offering those examples, you haven’t driven a wedge between disproportionate representation of the relevant sort and its to-be-avoidedness. If you fail to understand this point, and need me to spell it out for you in more detail, I will. Just ask.

As I explained in that comment, I’m genuinely interested in understanding people’s motivations. I’m not committed to the view, as you seem to think I am, that there is no reason to promote a greater male-female balance in philosophy. On some ways of articulating the project, I’m all for it! And I try to be conscious of how engaged my various students are, and whether certain things I do change the dynamic, etc. It’s just that I’ve noticed some odd trends in this sort of advocacy that don’t seem to make much sense.

At no point did I say that there can be no good reasons for wanting to spread an interest in philosophy among different demographics. I posted a couple of prompts to solicit a certain range of moves. You and others supplied them. I think the moves you made are interesting but, in the end, ineffective. I was near the end of writing out a long explanation of why, but then my computer crashed, erasing everything I’d written, and I’m not particularly motivated to write it again. But I do plan to write something about this elsewhere, and I thank you for contributing your three-part condition, which I plan to address there.

I recommend paying more attention to the difference between failing to understand an argument and being unimpressed by that argument.

Oh dear… the good old ‘I would have submitted my work, but then my computer crashed…’ excuse that I try to get my freshmen to stop using.

I won’t be checking out your work somewhere else, for you haven’t told us where to look. But I’m familiar enough with your commentary here to be confident your work is unlikely to be worth my time.

I’m curious—with the movie analogy, you seem to imply that there’s some “content” we could remove from philosophy to make it more palatable to women, and that nothing of value would be lost when getting rid of that content. What do you have in mind?

No, I’m not implying this. This is the dialectic as I understand it. He attempts to pose a problem for opposing the underrepresentation of women in philosophy. This is the argument I think he would need for the problem to be interesting:

1. There could be good reasons for opposing the phenomenon

of underrepresentation in philosophy only if there could be good reasons for opposing the phenomena in the examples.

2. There couldn’t be good reasons in the examples.

3. So, there couldn’t be good reasons for opposing the phenomenon in philosophy.

I deny the second premise without implying the specific relationship between my conditions and the phenomenon in philosophy, to which you refer. Notice, however, that my conditions suggest there *could be something* to change about philosophy, just as there could be something to change about the movies in his example.

Jen, I already explained, six hours before you posted this, that I am not making that argument at all. I was asking a question (as I had already explained before the last explanation) to try to understand the motivation.

But here you go, swaggering around telling people what I would need “for the argument to be interesting.”

Does it occur to you that, perhaps, some other people find the question (not argument) interesting for reasons you might not? Why be so aggressive and self-confident?

And then there’s your smug swipe that my commentary is “unlikely to be worth your time” (though you seem to have endless time to respond to it here), and your insinuation that I made up the bit about my computer crashing because… what… you think your response was so devastating that there was nothing to be said against it? Really? You’ve been taking an awfully arrogant line here against a number of people. I don’t know why you think you’re in a position to look down upon us, pityingly and condescendingly. Enough. Why not just get your point across without all that?

For the record, here’s the main point I wanted to raise against your earlier reply, before it got cut off:

The essence of your response was, by analogy, that philosophy confers something of great benefit to those who study it, and that nothing else can supply that great benefit; therefore, we clearly have an obligation to push for the equalization of rates of male and female study of philosophy.

Two rejoinders:

1. If the goal really is to spread the goods of philosophical study more widely, it seems difficult to defend this way of doing it. As we learned from Eric Schwitzgebel’s post here a couple of years ago, roughly 0.39% of university graduates today are philosophy majors, and slightly over a third of those graduating majors are women. So there we have it: this major that can do so much good to anyone who takes it is only chosen by one person in two hundred fifty.

By Schwitzgebel’s numbers, then, male philosophy majors make up about 0.26% of all university graduates, and female philosophy majors make up about 0.13%. If we were to increase the number of female philosophy majors to the point where there are equally many men and women in philosophy undergraduate programs, we would increase the number of philosophy majors from 0.39% to about 0.52% (a little less, really, because of the non-binary students who aren’t counted in either category). To put it another way, this would reduce the number of non-philosophy majors from 99.6% to 99.5%. Is that really the most effective way to ensure that those vast numbers of non-majors who are currently missing out on the irreplaceable benefits of philosophy begin to receive them? Wouldn’t it be much more effective just to popularize philosophy, full stop?

But in fact, balancing out male and female majors wouldn’t even do this! The goal of equalizing male and female majors might well be achieved by making changes that would reduce men’s interest, or perhaps by a female-dominant major like psychology or English finding ways to attract more male students. In that case, the ratio of male and female students could be equalized while the total number of majors stays the same.

More than that, we could even equalize the number of male and female students while *reducing* the total number of philosophy majors. This might be the easiest way to do it, in fact, since we wouldn’t need to persuade anyone else to take the major. We could simply count up the number of female majors in any given department, and limit the number of male majors to exactly that number. All the other male majors would need to go elsewhere.

Hence, if the purpose is to improve more people’s lives by giving them the gift of philosophy, this doesn’t seem to be an effective way to achieve that.

2. I don’t have time to pursue this other line fully here, but it seems at least a little strange to me that so little concern is given to the apparently autonomous choices of students.

Suppose, by comparison, that I try an amazing new superfood, and feel that it has changed my life for the better. I become a great advocate of it, constantly telling my friends and co-workers about how much it will improve their health — and so delicious, too! I provide them with literature supporting it whenever I can, and I also strategize on ways to get people to try it. Some people try it but don’t like it: I try to get them to stick with a three-month intensive diet with the superfood as the main component, so that they can *really* find out how amazing it is. Other people like it well enough, but just say they’re not interested in making a commitment to it. I spend a great deal of time scheming to get them to consume it more often.

Even if I’m right that eating the superfood regularly would confer amazing health benefits that people can’t get anywhere else, this strikes me as somewhat disrespectful of people’s free choices. They’ve heard my pitch, maybe tried the food… I can maybe try one or two more things here and there, but if they say they’re just not that into it, it seems to me that I should respect their judgment even if I believe that it will leave them worse off.

I’m not sure whether your food analogy is symmetrical with some of the proposals. But even if it is, how would you reconcile that with what schools are doing with other subjects such as math, English, history, etc.? These subjects have been shoved down students’ throats since first grade despite the fact that different students have no interest in some of these subjects.

Do you think these subjects are okay to require students to take or do you feel the same way about them?

Thanks for the comment, Evan.

I’m not quite as concerned about generally required courses. In fact, I’m one of those outliers who think it wouldn’t be so bad if we went back to something like an option-free curriculum at university, for various reasons. If the idea is to require everyone to take a certain number of philosophy courses, so that we all learn the great things philosophy has to teach us, all right.

But at a certain point during or after university, people are given the free choice to decide what to study or at least what careers to pursue. If we are serious about giving people that freedom, then it seems to me that we need to be comfortable with the fact that members of some demographics will like certain areas of study or employment more than members of other demographics.

Of course, as I made clear, there are some things — sexual harassment, blatantly sexist comments, etc. — that are I think rightly condemned by everyone as having an unacceptable influence on people’s choices and generally making things worse. Let’s get rid of those things. But once we have, there’s no guarantee that the free decisions will fit the desired social pattern. At that point, we must either remove free choice or else accept unequal representation.

I treat decently people I believe to be decent. I treat others otherwise, according to what I believe of them. (Notice, I’ve regularly treated other interlocutors, such as David Wallace, well because they treat others well.) I noticed in the past that you treat dismissively and disrespectfully people you believe to be your political opponents. So when I deem it appropriate, I treat you similarly. Potentially, you’ll begin to change your behavior. (Sure, you’ll still mistreat me in retaliation. But it’s worth it. That’s why I spend time responding to you, not because your work/commentary is worth my time.)

Now you know why I respond to people as I do. I know you’ve grown tired of me. My advice is to treat your political opponents and other interlocutors fairly.

Judging by what you regard as “the essence of my response” to your examples, you still haven’t understood what I was up to, despite the fact that I laid it out for Prof L.

Anyway, your rejoinders seem to miss the response you’recalling mine, at least on one interpretation of it. Here’s what I have in mind:

For many who reach the highest levels, I believe, philosophical study increases levels of analytical skill and clarity of thought to a degree that allows them to live a fulfilling life, and no other activity is likely to confer the same benefit to them. (The number of such benefactors need not be high.) As the number of people who study philosophy increases, the number of potential benefactors increases. In the absence of sufficient reason for believing women are likely psychologically incapable of benefitting from philosophy at the same rates as men, we should work to ensure they have equal access to the opportunity to benefit from it. We should, therefore, oppose the underrepresentation of women unless and until they have such access. And things that likely pose obstacles to equal access, such as a culture of sexism, thus should be opposed for this reason (among others, of course).

This line depends on an account of equal access that I have not as of yet articulated. Still, both of your rejoinders completely miss this point. The first does because it interprets the scope of the response too broadly: the claim is not that *all* who study philosophy are the benefactors, but merely that some are. The second does because it falsely assumes that the response requires deception or loss of autonomy.

Jen, your comments and representations of me are getting more and more ridiculous as we go. I’m not the only person you’re doing this to. I see that you disagree: fine. You believe what you will, and I’ll gladly leave it to readers who have seen this conversation to form their own assessments. Enough.

I suppose there is an alternative explanation of many (although not all) of my observations of your behavior, but you wouldn’t want me to mention it here. You’d likely regard it as a personal attack and the comments might soon afterward get closed. But since I’m willing to accept the alternative as satisfactory, here’s a proposal: I’ll relent until I notice further dismissive or disrespectful behavior from you. You can accept my proposal by responding affirmatively to this message today. If you do not respond affirmatively today, I’ll take that as a rejection of it.

It sometimes seems that you’re intentionally getting things wrong in order to make your interlocutors appear incorrect or foolish. Here are some examples from this comment.

1. You wrote, “Jen, I already explained, six hours before you posted this, that I am not making that argument at all.” This would be true only if you had denied making any of the claims in the argument I laid out. Yet, you never did. The closest things you wrote were these:

“At no point did I say that there can be no good reasons for wanting to spread an interest in philosophy among different demographics.”

“I’m not committed to the view, as you seem to think I am, that there is no reason to promote a greater male-female balance in philosophy.”

Neither of these is the denial of any of the claims of the argument. So, it seems, either you’re intentionally being deceptive in order to make me look foolish, or you’re very sloppy in your thinking.

2. You wrote: “But here you go, swaggering around telling people what I would need “for the argument to be interesting.” Does it occur to you that, perhaps, some other people find the question (not argument) interesting for reasons you might not?” But I didn’t write ‘for the argument to be interesting’. Instead, I wrote ‘for the *problem* to be interesting’.

Not only is what you quote inaccurate, but it suggests that I made the mistake of calling a question “argument” in what I wrote. But I made no such mistake, and in fact, you did attempt to pose a problem using those examples. (Of course, you claim you weren’t attempting to pose the problem I attribute to you, but you we’re still posing a problem, the one I attribute or another.) So, I in fact made no mistake in the words I wrote. Again, it seems that you are either sloppy in your thinking or intentionally being deceptive to make me appear foolish.

3. You wrote: “The essence of your response was, by analogy, that philosophy confers something of great benefit to those who study it, and that nothing else can supply that great benefit; therefore, we clearly have an obligation to push for the equalization of rates of male and female study of philosophy.” Really, ‘we clearly have an obligation’? Here are the closest things I wrote:

“For these reasons, the content might be objectionable enough that the movies should be changed to remove the content.”

“This is enough to make pressing the button an improvement.”

Neither of these comes even close to being ‘we clearly have an obligation ‘. Again, then, it seems that either you are very sloppy in your thinking, or you are intentionally being deceptive in order to make me appear foolish.

I assumed you we’re intentionally being deceptive. But I’m beginning to consider rejecting that assumption. You know what the alternative explanation of your behavior is. Do you still question why I think I’m in a position to look down upon you pityingly and condescendingly”?

Do you question my grounds for regarding your work/commentary as likely unworthy of my time?

How highly should I think of you and the people who “like” your comments?

Thanks for pointing this out. I also feel the same way about some people on here. Strange how some people on this site have no problem pointing errors in their students thinking, but when the table is turned on them they can’t or refuse to see it.

Your comment is professional and generous. Most people would not bother helping others see their own errors.

I would think that having spent years doing philosophy, some of these people would be more cautious in their writing, reading, and thinking.

People tend to rush to respond more than understand. That, I think, is impulsive and shows a lack adequate self-control and hence is irrational. We’re not being autonomous if we’re mostly impulsive like that. And I truly pity those who lack such autonomy.

Yes, there are many people who are guilty of this stuff. (There are also many who are more careful.) I agree that it seems a bit strange, but it also makes some sense that not everyone takes very seriously their reading, writing, and thinking when engaging in conversation on blogs.

It certainly may be correct that he and others respond impulsively, but I suppose it could instead be that they (falsely) believe they’re better than their opponents, and so underestimate the quality of their opponents’ abilities, beliefs, attitudes, etc. This might, I turn, make them overestimate the quality of their own abilities, beliefs, etc. I’m not sure what to think.

Hi Justin. I just want to express, publicly and where it has taken place, my sympathy with you over the treatment you’ve received in this discussion. It was not called for, and you have been a model of restraint in responding to it.

Jen and Evan, I’d be happy to talk about why I think this way privately. Feel free to email me. But beyond expressing this point of solidarity, I see no more reason to speak on this subject publicly. So if you’d like, please have the last word here, and by all means send me an email if you want to talk more with me about why I’ve said what I have.

It’s no surprise that you would express sympathy. You were one of the bad actors in a prior discussion. I couldn’t care less about what you think.

Interesting you say that because 8 months ago you wrote this to me. See. Pic. Your previous attitude about inquiry and free speech seems to contradict your present attitude/argument.

Did you have a change of heart? Would you still think your refusal to engage publicly about this issue “childish and immature, unbecoming of a well-functioning adult member of society” like you wrote before?

I never singled out anybody. But Jen provided justification for her claims about Justin Kalef. I’ve engaged on this website for less than a year and I’m assuming she and him have been at this blog longer. If what she says is true, then it’s become a habit and hence character issue.

Granted, I did do a Google search of Justin Kalef and found out he had similar issues with others in the past by other bloggers. This problem seems too persistent to ignore and may make commenting hostile and frustrating. Hopefully, we can all learn from this.

Hi Evan. No, I still think it is childish and immature to speak of university students in the U.S. today as “emotionally triggered marginalized people” in need of “coping” mechanisms when faced with the results of inquiry they prefer not take place. I understand some people disagree with me about this. But that’s my view, and it’s part of what I take to be a ground for the open discussion of the problems we face that such views can be entertained publicly.

Concerning the treatment of Justin here, however, I simply think there’s little to be gained from discussing it further in this venue. That isn’t a matter of suppressing what you’re calling here “inquiry and free speech”, or what you earlier referred to as “absolute free speech”, but rather one of the appropriateness of that kind of conversation in this venue. I also have some concerns about what social media does to our natural habits of association and concourse when we disagree with one another in public fora over exchanges like the sort above.

But as I said, I’m happy to converse offline. I’m using my real name, so you’re welcome to reach out to me if you’d like. And you can continue to use a pseudonym if it suits you.

Then we don’t really have much to discuss further. I’ve said what I said and Jen said what she said.

Of course, I can personally remonstrate to these people privately. But I doubt doing it privately would change their character if they hardly improve via being called out in public in the first place. I have no interest in continuing, but if somebody continues to strawman others, it’s appropriate to point it out publically.

Point out what, Evan? You point vaguely to character flaws you’ve diagnosed in me, and errors you’ve diagnosed in things I’ve said. But you don’t explain where my reasoning is meant to go wrong or what exactly I’m meant to do that is objectionable. You mention other people who have written things against me. Fine — when one says things that go against the grain (as I hold it is out duty as philosophers to do, just as I hold that it is our duty to support others in doing, when they present reasons for their views), there will always be people who get annoyed and who will come up with reasons for attacking one. But do those attacks have any merit? That’s the question: this isn’t a popularity contest. Nothing that you have presented indicates that you have given that matter any independent thought. Instead, you hide behind your concealed identity ad throw out mild comments about the character of people who are not similarly hiding behind pseudonyms.

As for Jen’s last few comments, or really anything at all that she has been saying and the way she conducts herself in these conversations, I still don’t think there’s anything I can add to the conversation with more comments that will make clearer what she is already making so clear herself. If anyone reads through this or any other exchange I (or Preston Stovall or Spencer Case) have had with her and comes away thinking that she has made some good points, I’m not sure what I could say that would help clarify things. The record as it stand already speaks for itself, and each of Jen’s additions to it seems to make it clearer rather than more ambiguous.

We are all meant to be philosophers here. We are unusual people who share an analytic bent, an eye for tensions and anomalies and the curiosity to inquire into them. Among us, there should be no mystery about why I do that. The puzzle is why there are domains in which a dominating narrative should be accepted by so many philosophers, any self-described philosopher would *not* wonder about things and raise questions.

We’re talking about complex social issues here, not pure logic. The odds that there would be nothing worth raising questions about is practically zero. Where there are whole areas in which few people seem to express any doubt at all about the dominant moral picture — especially when, as here, that moral picture is rejected by the majority of the population across all major demographics — it’s natural to wonder whether, say, the threat of character assassination might be a factor. Your offhanded tendency to presume that my character needs repairing, just from what you know of my from the questions I ask, is a helpful sign. But as with Jen, I think the record of this very conversation is already sufficient for anyone interested in looking into this.

The beauty of hypothetical syllogism is that it doesn’t guarantee or necessarily indicate truth. If you read carefully, I said, “If what she says is true, then it’s become a habit and hence character issue.” The “if” here is important because it leaves open the possibility of whether or not what she says about you is true.

I don’t actually know whether you’re perpetually like this. Hence why I said, “hopefully we can learn from all this.” But IF you are, then it’s a character issue and I strongly recommend you work on that.

Last, this issue really isn’t about general disagreement. That’s fine. You can be as contrarian as you can be. I welcome it. I’ve read a lot of arguments and many things aren’t new or surprising to me.

But what I get from Jen was that you keep straw-maning and misrepresenting her arguments. She provided detailed evidence. So please read her words more carefully next time.

“I don’t actually know whether you’re perpetually like this. Hence why I said, “hopefully we can learn from all this.” But IF you are, then it’s a character issue and I strongly recommend you work on that.”

I am perpetually the kind of person who notices anomalies and unexamined presumptions, and who raises questions about them and tries to figure them out. Yes, it is a character issue that sets me apart from most people. My way of ‘working on that’ has been to become involved in the world of philosophy and ply my trade there, meanwhile minimizing the time I spend on people who for some reason also call themselves philosophers despite opposing that cluster of character traits. It’s been working out quite well, thank you.

“But what I get from Jen was that you keep straw-maning and misrepresenting her arguments. She provided detailed evidence. So please read her words more carefully next time.”

I’m sure that you would get that from Jen if you read her words and took them to be an accurate representation of what happened. But they are not, and any reasonably perceptive person who open-mindedly compares what she said with what I actually wrote would see that. I did, in fact, read her words very carefully when she made those accusations. I went back and reviewed our most recent interaction to see whether there was any way in which she could be said to have made a point. I found that she did not. I intend to spend less time, not more, thinking about what she says in the future.

Since you presume to give me advice, I’ll return the favor: it’s worth keeping in mind that anyone can make a compelling-sounding case that he or she is being misrepresented if one is willing to take his or her word for it, and it’s not that difficult to provide detailed evidence for one’s claims if one doesn’t have to ensure that that evidence is any good or that the details are true.

Take care.