Philosophy Professor Resigns to Protest University’s COVID-19 Plan

Jeremy Fischer, who until yesterday was a tenured associate professor of philosophy at the University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), resigned from his position to protest his university’s COVID-19 policies for the coming term.

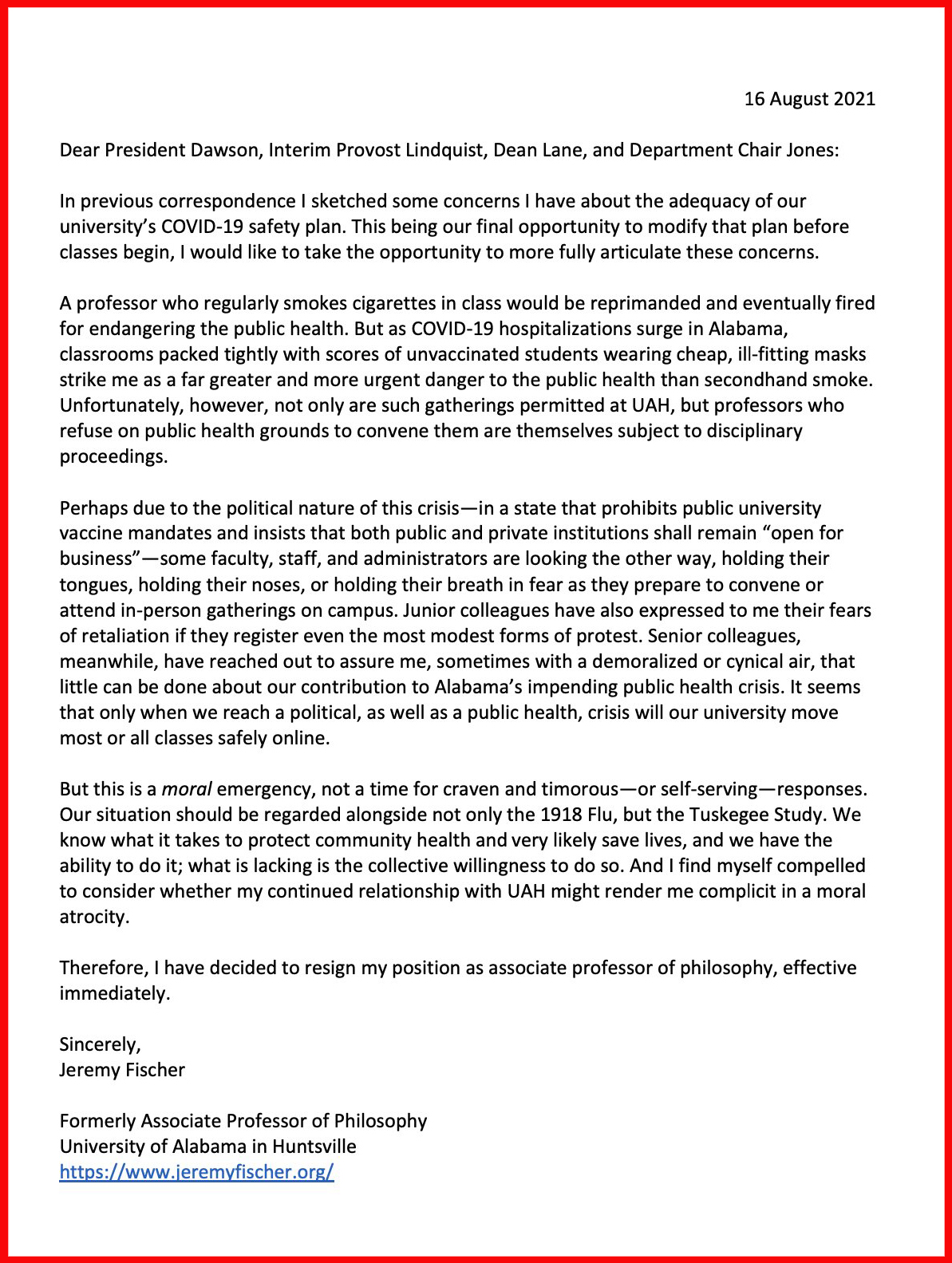

Writing to his university president, provost, college dean, and department chair, he said:

We know what it takes to protect community health and very likely save lives, and we have the ability to do it; what is lacking is the collective willingness to do so. And I find myself compelled to consider whether my continued relationship with UAH might render me complicit in a moral atrocity.

Therefore, I have decided to resign my position as associate professor of philosophy, effective immediately.

Jeremy Fischer

Dr. Fischer had described UAH’s pandemic plans last month in a guest post here, “Sounding the Alarm: 2021-2022 COVID Risks at Unprotected Colleges and Universities” and launched a petition to urge the University of Alabama system to strengthen its COVID-19 safety protocols. In that earlier post, he wrote about the implications for his university of Alabama SB 267, signed into law on May 24th of this year, which prohibits state-funded schools from requiring students to be COVID-vaccinated.

While UAH reformed some of the policies discussed in that earlier post and has now implemented an indoor mask mandate,* Dr. Fischer wrote, in an email:

I remain concerned about my former institution’s (1) lack of vaccine mandate (and its unreported, but likely low, student vaccination rate), (2) lack of re-entry COVID testing at the start of the semester, and (3) lack of regular COVID-testing of the unvaccinated throughout the semester; as well as (4) its refusal to implement social distancing indoors in accordance with C.D.C. recommendations for universities where not everyone is fully vaccinated, and also (5) its refusal to move substantial numbers of classes, especially large lecture classes, online, even when the instructor would prefer such a move.

Dr. Fischer, who specializes in moral psychology, ethics, and the emotions, voiced concerns about faculty complicity in a public health crisis, asked about whether instructors at unprotected institutions are morally permitted “to risk the public health in order to convene philosophy classes,” and suggested that faculty might consider resigning in protest.

Yesterday, he did just that. He announced his resignation on Twitter. His resignation letter is reposted below in its entirety:

You can view UAH’s current COVID policies here.

In response to follow-up questions, he emailed:

Perhaps you might direct sympathetic readers to support the email campaign I have been urging. People can email the leadership of my former institution, UAH, and of the UA System more generally, and urge them to adopt the sensible COVID policy of our neighboring university, Alabama A&M: among other things, (1) moving courses online for the first two weeks of the semester and (2) mandating weekly random-sample (“sentinel”) testing of the unvaccinated thereafter. We also urge the adoption of (3) universal social distancing mandates that accord with C.D.C. recommendations for institutions of higher educations where not everyone is fully vaccinated.

Here are a few key decision-makers (and their public email addresses):

Darren Dawson, President, [email protected]

Robert (Bob) Lindquist, Interim Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, [email protected]

Kristi Motter, Vice President for Student Affairs, [email protected]

Finis St. John IV, Chancellor, [email protected]

Members of the Board of Trustees, [email protected]

He also encouraged faculty—especially senior faculty—to form “local ad hoc COVID-policy committees” on their own campuses with their colleagues and to reach out to university unions, faculty senate committees, and school administrations with their concerns. He warned, “what is happening in the Deep South may well be coming soon to a town near you!”

* The original version of this post did not mention this update to UAH’s policies.

If all philosophers had this moral courage it would be a different world.

I commend Dr. Fischer for his commitment to acting on his very strong belief that UAH’s policies pose a serious if not catastrophic public health risk. I hope his actions are publicized and persuade students to get vaccinated, if they are not already, and to mask up.

I do have some questions: Is Dr. Fischer the only faculty member at UAH to tender their resignation? What are faculty with similar concerns doing? While it is clear the administration is not doing much, I wonder what efforts faculty who share the sense of imminent risk are undertaking to persuade those who remain unvaccinated and unmasked to change their practices with respect to the pandemic.

Have you been able to answer your questions? Or were they just rhetorical?

An incredibly brave move (though not out of character for Jeremy). I hope some department at a better run university is able to offer him employment soon.

tragic that faculty moral will and solidarity are so weak across the country that instead of general strikes we have instead this kind of individual sacrifice…

My understanding is that SB 267 prevents vaccine mandates under state law. UAH currently requires masks indoors, for both vaccinated and unvaccinated.

So, at least in those regards, there’s constraints on what it can do in the first place, and it did the major thing that it could do (i.e., require masks indoors).

Moving online at the beginning of the semester, weekly testing for unvaccinated, and social distancing shouldn’t be so controversial.

Though I admire his courageous action, I do wonder what, ultimately, we are to do. When I look to, on the one hand, Israel and other highly vaccinated places and, on the other hand, to Australia and other highly self-isolating places (that have been very successful so far), I become very skeptical – by which I mean – Delta changed the whole game completely. I do not believe there is any stopping it anymore. What we can do is, more or less, make sure that the vulnerable (older and pre-existing condition) population is fully vaccinated, but beyond that it’s simply delaying the inevitable (unless, by miracle, we would get 100% vaccination rate) – we can delay another 6 months but masks and lockdowns and so on, but it will come for us. At one point, we will have to resume living, travelling, socializing and it will come. I think the sooner we now come to terms with this, the better. It’s a terrible situation.

Yes, I agree with this sentiment. Sadly, it seems that identity politics on the left is holding back the widespread realization that this is where we are at. Earlier in the pandemic right wing identity politics was the main problem prompting people with that identity to take silly stances on COVID not based on evidence or conservative principles but simply on their need to maintain a “right wing” identity opposed to the left. There is, of course, much of this right wing silliness still around. But now, as the situation changes, some of the things that were initially embraced by those on the left no longer apply so clearly, and the correct position seems to require a partial shift towards some of the right wing positions about living with the virus and accepting some deaths for greater liberty. Unfortunately, many on the left are unable to unbiasedly consider the reasons that supporting changing our approach in this way because their identity is tied up with virus policies from last year that were associated with the left and opposed by the right.

If we have to accept some deaths for greater liberty, as you suggest, may I modestly propose that we start by accepting the deaths of those who, like you, advocate that we ‘accept’ otherwise preventable deaths? Seems only fair to lead by example…

I don’t think COVID deaths are transferrable that way…

Not yet, anyway. Just wait until the Omega strain arrives, though!

If you think COVID politics is divisive now…

Wait until they start blaming brown undocumented immigrants for the virus! Oh wait…

Justin may want to consider removing this comment.

I think the commenter intended it as tongue-in-cheek (note the “modestly” reference). Besides, it’s not as if a related idea hasn’t been considered in the philosophical literature: https://academic.oup.com/pq/article-abstract/70/281/850/5782388?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Your blog, your rules. I find the comment more repugnant than accepting utilitarian tradeoffs, but YMMV.

Exactly right! Just a repurposed joke-pattern from the ancient Greeks filled in with today’s referents and an explicit allusion to Swift to make the humorous intent obvious, but one’s knowledge of the history of philosophy, literature, and satirical traditions may vary…

I got the reference (it was implicit though, not explicit). My knowledge of history of philosophy and literature is fine, thanks. The fact that it was a joke is far from obvious but if you say so…

The article Justin linked us to isn’t a joke, and if you’re as mortified by the suggestion as you claim to be, consider authoring a reply to that author’s piece. In my case, I was simply applying the following line of humor to an earlier post:

“When he was being initiated into the Orphic mysteries, the priest said that those admitted into these rites would be partakers of many good things in Hades. ‘Why then,’ said he, ‘don’t you die?'”

Ultimately, it is a matter of profound indifference to me whether you’re persuaded that I’m joking. Here’s why:

“He was asking alms of a bad‑tempered man, who said, ‘Yes, if you can persuade me.’ ‘If I could have persuaded you…I would have persuaded you to hang yourself.'”

If you think that’s repugnant, wait until you read the brief account of the life of Timon in Plutarch’s Antony. There’s a public service announcement involving an olive tree that’s either hilarious if you have a funny bone or scandalously repugnant if you’re tone-deaf…

Yeah, okay. Cool.

I’m having trouble seeing where this hostility is coming from. We enact policies all the time that allow some preventable deaths in order to achieve other goods. For example, by permitting people to build swimming pools in their yards we allow several hundred drowning deaths to occur each year that could have been prevented by banning such pools. We do this because we think that other goods that come from permitting private pools outweigh the deaths they cause. Indeed, the same thing appears to apply to whatever COVID policies you support. For example, perhaps you support very strict lockdowns in response to each COVID outbreak in order to prevent deaths. But even the strictest lockdowns we have seen in the West do no compare to the much stricter lockdowns that China has used to curb its outbreaks. Yet I presume that you are not in favor of China-style lockdowns even if they can prevent more deaths. And the reason for this is obviously that the marginals gains in deaths prevented by opting for a China-style lockdown over the strict, but not that strict, lockdowns that you prefer could not justify the significant sacrifices of other things we value in a China-style lockdown.

So, the idea that we must make tradeoffs between preventing deaths and preserving other things we value is not a controversial idea but something inescapable that everyone is committed to. The controversial question is where to draw the line in these tradeoffs. But all I have said on this matter is that (1) the policies supported by the left last year made this tradeoff correctly in my opinion, whereas those supported by the right (or perhaps its populist wing) did not, and (2) as circumstances change its seems to me that some on the left are no longer being consistent and sticking to the tradeoffs they endorsed last year, instead they are supporting the same policies as before (perhaps for identity politics reasons) even thought the tradeoff of deaths prevented vs. other goods sacrificed has fundamentally changed.

Now maybe there is good evidence against my claims. I’m open to hearing such evidence and changing my mind. But I don’t understand the hostility in your reply.

Any time a student of mine dismisses someone else’s moral claims with “identity politics,” “just what old white men think,” “wokeness” in a written assignment etc I dock them a good 2/3 of a grade at least for laziness and an egregious violation of the principle of charity. I’m glad they don’t read philosophy blogs because what would they do if they knew that people with graduate degrees in philosophy won’t hold themselves to the same standards I expect a seventeen year old in 101 to follow to even get a B in that class?

You might not like the term, but you can hardly deny the phenomenon. Society is becoming more divided by the “political tribes” we belong to. Our membership of these tribes is becoming an increasingly important part of how we identify ourselves and who we associate with. This is resulting in people adopting certain positions on social issues not because these positions follow from their fundamental values, or are supported by independent evidence, but simply because taking these positions is a way to mark their identity in the political tribe they belong to and take a stand against those in the opposing tribe.

How much this is going on in various societies is up for debate. But you can hardly deny that it is going on at all.

“You might not like the term, but you can hardly deny the phenomenon.” That may well be true– though it’s hardly obvious and you offer zero evidence for it. But let’s suppose it is and that political tribalism is as rampant as you claim. Even if we grant that you can’t cite that fact to just dismiss people’s moral positions. That’s an ad hominem straight out of a 100 level critical thinking textbook. (I’m sorry if this is condescending but it’s true). You actually have to do the hard work of examining those claims and seeing if they stand up to scrutiny. And the fact is that there’s an easy way to prevent COVID deaths generally without any of the bad stuff you gesture at– vaccine mandates (while we’re at critical thinking level mistakes the claim that we have to choose between “freedom” versus “Chinese level repression” is a complete howler of a false dichotomy). I can see no compelling argument whatsoever that all students shouldn’t be required to be vaccinated against COVID as they are for measles, mumps, whooping cough etc. I take it Alabama banned that sensible response on a state level so the only responses left are pretty kludgy but they’re better than nothing. At any rate if you have an actual argument against vaccine mandates at colleges I’m all ears, but don’t trot out “tribalism.”

I will file this under “another case of someone on the internet accusing another of committing the ad hominem fallacy by themselves committing the ad hominem and falsely attributing several uncharitable claims to their target”.

On a more serious note, the tone of the responses I have gotten here has led me to realize that this is a very emotionally laden topic that requires a significant level of sensitivity. Those of us who live in, and have all our loved ones in, countries that have handled the pandemic very well with very few deaths can fail to see how raw the feelings might be for those living in countries that have had a different experience. In such circumstances, even if you have a reasonable point to make, you should be careful how you word it.

Of those three expressions, JTD only used one—”identity politics”. While the term may have been misused here, the phenomenon of tribalism that they were alluding to is not only real, generally, but particularly evident around COVID. Do you disagree with JTD’s description of the phenomenon or just with the phrase?

I think the use/mention distinction might be relevant here. I take it JTD was mentioning identity politics, not engaging in it.

Suppose I said, “Hey, driving is worth it, even if it means some people are going to die. Allowing people to drive is overall a good deal despite problems of risk and death.”

And suppose you said, “If you think that, let me modestly propose that you be the first to die.”

That would be a really dumb and mean thing to say in response, no?

I should say that I do not see the situation in terms of left and right politics, or liberty or whatever (though it’s hard to avoid this bs, of course). It’s an issue of public health and the best management of that in view of other concerns. My thought is simply that Delta changed the situation and that the approach we had so far, which included massive reduction in social, educational, and economic activities of various sort, will not work anymore and so we need to adjust to the reality of it (however terrible that reality is). Delta is becoming or already is an endemic virus, we won’t get rid of it and, I suspect, at some point, all of us will get it (symptomatic or not), just like all of us will get cold or the flu. The concept of herd immunity needs to be junked here, this thing will percolate through the populace. At least so I think. My hope is that it will mutate to something less harmful in time. It’s all depressing.

One would assume that advocacy for high stakes policies that kill people in the absence of interference to prevent harm to others (this follows from your version of ‘liberty’?) requires extremely substantial evidence.

At the very least you’d need to explain how we preserve a value that outweighs the disvalue of a horrendous torturous death for some of those we fail to protect.

Just FYI– people pointlessly dying in agony when their deaths can be prevented is way up there in terms of terrible things.

I avoided reading philosophy blogs for years because it is so disheartening what some in this profession seem to think about the worth of their fellow humans.

So I cannot believe the one time I stumbled back into these conversations I come across a comment blithely suggesting without any evidence (or even explanation) that we’re going to have to kill a few people (or more than a few) to preserve a liberty (to do what exactly?) that cannot be curtailed even when its exercise will inevitably result in a pile of dead bodies.

And look at the upvotes.

I admire Prof. Fischer greatly.

Delta likely changed the game but far from completely. There’s no evidence, at this point, that a 100% vaccination rate is needed to “stop” the Delta variant nor is “stopping” it the only worthy goal. It wasn’t the goal of the “flatten the curve” strategy before the vaccines were discovered and turned out to be more effective than expected.

Iceland, with 71% of its population fully vaccinated, just had its Delta surge and, after just two weeks, is past its peak, with cases declining. On a per capita basis, this wave produced a low rate of infection compared to our Delta variant outbreak here in the US.

More importantly, Denmark’s high rate of vaccinations reduced the strain on hospitals and prevented covid-related deaths: so far, Iceland hasn’t reported a *single* covid death since May 27th and its hospitals weren’t overwhelmed.

We’ll see whether other countries with 70%+ of the population fully vaccinated experience similarly brief and relatively small Delta waves (without other, costly mitigation policies). What we do know is that high vaccination rates have made Delta waves less deadly and less overwhelming to hospitals in other countries, like the UK and Israel. These are the most important reasons to flatten the curve until we’ve achieved a higher level of vaccination.

As daily vaccines administered increase again in the US, and as hospitals, including pediatric hospitals, get overwhelmed in multiple states (the entire state of Alabama apparently has *no* available ICU beds), it makes as much sense as ever to reduce the spread of the virus. Indeed, it makes more sense to do this now that it’s certain to save lives and reduce pressure on hospitals than at the start of the pandemic, when it was unclear what kind of vaccines, if any, we’d end up with or how long it would take. It’s reasonable to expect more upticks in vaccinations when the vaccines are fully approved and when they’re approved for children under 12.

Lastly, not only would “flattening the curve” until we achieve a 70%+ full vaccination rate relieve hospitals, save lives, and likely lead to fewer infections, there’s also evidence that it would reduce the percentage of infections that cause long-term damage; see the last few questions in this interview, where Hampshire states that vaccination reduces the risk of a covid infection causing a long-term decline in cognitive function:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5aAbvSoBVpE

You can flatten it temporarily, as Iceland, Malta, or Israel, but it will come back once you relax the measures and hit back with another wave. Moreover, Delta does not behave like the old strain which basically needed multiple seeding in a country (so closing off borders worked) and relied on super-spreading events. With Delta – everyone is a super-spreader. Vaccination lowers the risk, but does not erase it and it spreads from vaccinated without detection too. So either you live the rest of your lives in lockdowns or accept a level of risk and death in a country. You cannot be flattening the curve for ten more years (or 20?). You have countries that are 70-80%+ vaccinated and surges that hit as high as before and no real idea about how to prevent them from re-occuring. There was a surge in Gibraltar with 100% vaccinated. The coming apart of hospitalization and infections is already here, but I seriously doubt it can be improved much from the current situation. In a very short term maybe, but once you look from a point of view of a year or two, it’s delaying the inevitable. I think it’s awful. I didn’t mind the measures till now but it’s becoming obvious that they are just postponing what will come in any case. Lastly, there are heavy costs to flatenning the curve – not just economical but on lives. In my country, it is now becoming painfully clear that a significant number of the deaths ascribed to Covid19 were not caused by Covid19 but by lack of proper treatment – due to pandemic – of other conditions people had so that, once they go covid, it finished them off quickly (and they were not treated properly). We made huge medical progress on many illnesses and closing things down for COvid is erasing them drastically too. So – I remain skeptical of the measures at this point. I am not skeptical of the usefulness of vaccines – to be clear – but I am skeptical of the point of lockdowns etc. at this point.

The OP isn’t calling for lockdowns. He is calling for “among other things, (1) moving courses online for the first two weeks of the semester and (2) mandating weekly random-sample (“sentinel”) testing of the unvaccinated thereafter. We also urge the adoption of (3) universal social distancing mandates that accord with C.D.C. recommendations for institutions of higher educations where not everyone is fully vaccinated.”

It seems to me as if your comments and those ofJTD present a false dichotomy – we either have to accept deaths and resume normal life, letting Covid sweep through and do its thing, or face lockdowns. Surely that’s not right; measures like masking, vaccinations, and testing allow us to continue normal life without lockdowns while controlling the rate of the (inevitable) spread of Covid, including variants like Delta. This is the exactly the sort of thing that will help hospitals to dedicate more resources to non-Covid illnesses, as it helps prevent them becoming suddenly swamped by Covid patients.

You write, “You have countries that are 70-80%+ vaccinated and surges that hit as high as before and no real idea about how to prevent them from re-occuring.” I’m not sure what information you’re referring to, but just as an example, I’m in the UK. Something like this has happened – we have a very high vaccination rate, and also our cases have surged since almost all distancing, masking and lockdown restrictions were lifted. Crucially, however, our hospitalization and death rates have *not* surged to anything like previous levels – they are much, much lower, which is presumably due in large part to vaccinations.

I think UK is doing the right thing – lifting almost if not all measures. It has come to accept the situation, abandoning the zero cases strategy which still dominates much of the approach elsewhere – incl. many states in US, Australia, NZ, much of South/East Asia and so on. I think if you just think of masks and such you are missing the point. Look at Israel – sweeping travel restrictions back in place, mandates for mask policy and closures again. US still has a number of travel restrictions (not open to Europe and other countries, etc), refugee acceptance, and many other restrictions in place. It is still effectively in lockdown from a certain point of view and for certain people and purposes. The online classes and all – it’s taking terrible terrible toll on children, esp. in poor circumstances. Nobody has doubted the benefits and need for vaccinations here, btw.

I hear you on the point that the negative effects of lockdowns are themselves devastating, and I sympathise with a lot of your points. But your comment still strikes me as suffering from a bit of black-and-white thinking. For instance, regarding online classes: yes, this has taken a terrible toll on some, especially children who have had only online schooling. But moving university-level classes online for a couple weeks at the start of a semester to allow extra time for testing/vaccines? Or even just large lectures? This doesn’t seem to me to have a comparably terrible toll, especially if, for instance, students are on campus with access to resources (I appreciate it has negative consequences for some students, but it benefits others e.g. those with various disabilities for whom remote study is easier, so it’s not at all obvious that on balance this has a ‘terrible toll’).

(Side note – the UK is a in strange hybrid place policy-wise – everything is open, and masks and distancing are no longer legally mandated, but individual businesses have the power to mandate them. We also still have travel restrictions with compulsory quarantine depending on the country of origin, and there’s a plan to require people to have had vaccines to go to nightclubs as of next month.)

I live in California – here, the schools and universities have been closed since April 2020. So more than a year by now. No in-person anything. I can’t stress how damaging that has been (at least they kept offering food) and, frankly, not sure for good reasons (when compared to many countries that kept schools mostly open). We have a elementary school for kids with disabilities (coupled together with a regular school) nearby – they have been cut off from social interaction – it’s harder, much harder for them actually – the loneliness. They are kids who want and need to play and have fun and socialize, not machines to learn stuff.

I agree that large lectures could be online (I don’t see the two week postponement point though). But I would like to emphasize that Delta is a very different sort of fish now – it just cannot be stopped and, in my view (taken from many scientists), any flatenning is just temporary – once relaxed, it will flare up and spread like wildfire, and do so in waves. It will spread even in a more or less fully vaccinated population. The lessons from Israel and Australia are there to see. THe only way forward is heavy vaccination of course, to reduce the stress on hospitals and deaths, but in many countries those who wanted to be vaccinated are basically vaccinated. What more is there to do, short of compulsory decree and shifting vaccination to Africa and countries who are basically exposed without protection now?

The situation for children like that has I’m sure been incredibly tough. I’m sad for the impact this has had on them, and agree that that counts strongly in favour of avoiding closing schools and full lockdowns.

But I’ll just pitch in once more. The part of your comments that I’m still not quite understanding is the claim, which seems to be implicit (but maybe I’m misinterpreting you) that since the Delta is so infectious and will spread and everyone will get it at some point once restrictions are eased at all, there’s no point having any restrictions. But here’s where I disagree (or maybe there’s something I don’t understand). Insofar as some restrictions are (1) not horribly costly (e.g. closing schools is very costly; wearing masks in crowded indoor places is not very costly) (2) slow down the *rate* of transmission at the population level, it seems this would help stop hospitals getting overwhelmed. This is true even if eventually everyone gets infected – it just helps spread out the infections over time to make it more manageable. I guess a crucial assumption supporting this line of thought is that once you have been infected, you are *less likely* to get it again and/or as badly, at least for some time. The science is still going on that, but reinfection rates seem to have been very low, and immunity appears to have lasted for at least several months according to studies (I don’t know the latest, but, e.g. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-52446965). If that’s right, then having some level of restrictions in place that reduce the rate of transmission is worthwhile, even if Delta is going to have to go through the whole population eventually.

I don’t think I disagree with you, actually. The difference might just be that (1) we have different restrictions in mind (coming from different countries) – I am thinking more of travel, transportation, borders, keeping schools closed totally, and so on. I have nothing against masks or shifting some things that can be shifted online without loss of “function” (it did miracles to DMV in US), and such, though I am a bit unsure about the efficacy of the usual ones – cloth – and the way they are worn esp. by children when it comes to Delta but masks are not an issue for me); (2) I am thinking more long-term perspective and the usefulness/harm of such restrictions from that point of view and their political feasibility/desirability (not in terms of left/right wing, but in terms of general societal stability and breeding of extremism). I should say that I have become much more skeptical than I was 2-3 months ago. Still, no disagreement on vaccines, or seriousness of Covid or anything like that.

What lesson are you drawing from Australia? They’re only 1/4 vaccinated – of course it’s a crisis there.

But at least they don’t have 100 deaths/day like the UK does. Avoiding that seems like a good idea.

That there is no hiding from this virus (esp. Delta now), ultimately – isolation, tracing, sophisticated lockdowns…ultimately, it’s just postponing. The only strategy is vaccination, at lest short-to-mid-term. I fear for Australia and NZ. I hope I am wrong and they will manage it. Long term, not sure.

If by “schools”, you’re including public elementary schools, then they haven’t been closed in CA since April 2020. My 7-year-old son went back to school, face to face, in April or May (I can’t remember which) of 2021. He’s also been back to face-to-face learning since the school year resumed, on August 16.

“The coming apart of hospitalization and infections is already here, but I seriously doubt it can be improved much from the current situation.”

Of course it can be. The higher the percentage of the population that’s vaccinated, the more it comes apart. Hence Iceland’s 0 covid deaths and our overwhelmed hospitals. States like Florida with 50% or lower vaccination rates are seeing daily deaths skyrocket again. And as I pointed out, daily vaccine doses administered are rising–and that’s without full FDA approval or approval for children. So flattening the curve is pretty much guaranteed to improve on the situation in this regard.

I can’t find much information on Gibraltar’s pandemic response, but its Delta wave was pretty benign and with what seem to be minimal mitigation policies (no work closures or stay at home orders):

https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/countries-and-territories/gibraltar/

https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/countries-and-territories/gibraltar/

Its number of cases during its Delta wave was extremely small. Its Delta wave peak of daily infections was under 1/5 of its earlier peak and was shorter. It’s recorded one covid death during its Delta wave. These data are encouraging about how much of a difference a high vaccination rate makes for living with the virus.

“In a very short term maybe [infections and hospitalizations can be pulled further apart], but once you look from a point of view of a year or two, it’s delaying the inevitable.”

As far as I can tell, this is pure conjecture. I see no reason why we can’t live like Iceland, or at least get closer to it (e.g., keep our hospitals from getting totally overwhelmed).

“In my country, it is now becoming painfully clear that a significant number of the deaths ascribed to Covid19 were not caused by Covid19 but by lack of proper treatment – due to pandemic – of other conditions people had so that, once they go covid, it finished them off quickly (and they were not treated properly).”

I don’t know which country is yours, so I can’t address your claim about covid deaths being over-estimated there. But the point you’re making about the pandemic hurting health care actually works *in favor* of the measures that are actually under consideration here (in contrast to lockdowns). Hospitals are overwhelmed with covid patients in many states–there are no ICU beds available. This means people have to wait longer for emergency treatment. And the responsible thing to do is to delay elective procedures. By flattening the curve as vaccination doses increase, and are poised to increase at a higher rate, we’d make our hospitals more able to heal people.

I think you need to talk to people working in healthcare. It’s correct that hospitals can get overwhelmed at ICU, but then walking through empty outpatient clinics and other hospital departments is also a consideration. People started to get procedures and treatments again in May/June/July and now that is under threat again.

So how do you get the vaccine to the people who simply refuse and won’t get vaccinated? It’s not an insignificant number.

“walking through empty outpatient clinics and other hospital departments is also a consideration. People started to get procedures and treatments again in May/June/July and now that is under threat again.”

Yes, this is one of my points. Allowing the pandemic to spiral out of control and overwhelm hospitals affects many aspects of health care. It’s forced Greg Abbott to ask hospitals to delay elective procedures:

https://www.texastribune.org/2021/08/09/texas-hospitals-elective-procedures-covid-greg-abbott/

“So how do you get the vaccine to the people who simply refuse and won’t get vaccinated? It’s not an insignificant number.”

This is the perfectionist fallacy. No one would claim 100% of Americans will get vaccinated. The point is that daily doses are increasing and are poised to increase again when the vaccines are fully approved and approved for children. All the available evidence points to our being able to achieve a degree of vaccination that would significantly reduce deaths, hospitalizations, and infections during future waves, relative to what we’re seeing now, even if we won’t things back to how they were in 2019 for the foreseeable future.

“allowing the pandemic to spiral out of control” – I am not sure this is fully up to us. I don’t know why it’s spiraling out of control in some places, like Texas and Florida, and in others it is not (like California or, for example, many Central European countries, that have very low cases and low vaccination rates) – or not yet. I think the evidence is mixed and I tend to read it much more pessimistically.

I think it’s worth remembering that even though US vaccination rates are way down compared to April, three quarters of a million shots (and rising) are still being given every day. That’s more than 10 million more fully vaccinated people every month – more than 10% of the population fully vaccinated between now and 2022. (And hopefully many more if the vaccine gets authorized for under-12s.) People sometimes talk as if everyone is either vaccinated already or refusing to get vaccinated, but that really isn’t true.

That’s true – it’s a good sign too, but at this rate, it will take till next year to get to 75% which is not enough for Delta and I assume it will slow down then too. Still, I am hopeful that more and more people will get the vaccine. I would actually be for compulsory vaccination.

Yes. The idea that the as of now unvaccinated are somehow morally vicious and deserving of illness or blame for the situation strikes me as one of the more abhorrent going around these days. Many people still can’t get jabs, including in the US, for a bunch of reasons, and many are susceptible to systematic contrary information from trusted epistemic sources.

Key point, right here, from David Wallace about the ongoing vaccination drive.

Moreover, Alabama vaccination rates are somewhat increasing, as the terrible truth sinks in:

https://www.al.com/news/2021/08/vaccine-rates-shoot-up-across-alabama-in-july-especially-in-rural-counties.html

Florida’s 50% vax rate puts it right in the middle of the pack. Statements like “states like Florida…” are at best unhelpful, at worst downright deceptive. Florida’s current wave is no joke. Low vax rates states are in for trouble at some point. Both these claims are true but make sure you get your facts right before drawing inferences.

All I meant to express with that phrase is that the situation in Florida shows that a 50% vaccination rate isn’t enough to avoid skyrocketing death rates. I chose Florida because daily covid deaths there are particularly high at this point. To me, that seems clear from the context I provided, but I’m not attached to the phrase. I’m not seeing any factual disagreement between your post and mine.

Fair enough. I don’t like the use of the term ‘skyrocketing’ here, but you’re right that being average on vax rates is not sufficient to prevent hospitalizations and deaths from rising. What isn’t obvious however is that this will not happen in states with higher vax rates. The evidence is not all that clear frankly, even though until two weeks ago I thought the decoupling with cases was self evident. I think what’s happening in Florida (and elsewhere) may only have a partial explanation in lower than desirable vax rates. Our (Florida’s) vax rates among the elderly is very high.

I also don’t know why in some states with relatively low vax rates, the cases are very low even if slightly rising (e.g., Slovenia, Croatia, Latvia, or Slovakia). I think there is no obvious answer available yet of what is going on and why.

People’s ability to draw causal inferences about extremely complex phenomena based on very shoddy data has been magically enhanced during the pandemic.

Florida’s vaccination rate is clearly only a partial explanation of the terrible outcomes there. I doubt there’s anyone who thinks vaccination rate is the only determinant of the rate of spread or any other outcome or that a, say, 60% vaccination rate guarantees a non-disastrous outcome.

What the data unambiguously show is that vaccines substantially reduce the rate of spread, death, and hospitalizations. That’s surely a major reason why Florida’s delta wave has been nothing like India’s (imagine if all those elderly Floridians were unvaccinated right now), the UK’s hasn’t been like Florida’s, and Iceland’s hasn’t been like the UK’s.

So will a state like Vermont’s delta wave be as bad as states with 50% or lower vaccination rates?? It’s possible but highly unlikely. I’d bet a lot of money on it being significantly less deadly.

I doubt there’s anyone who denies that vaccination rate is a determinant of the rate of spread or any other outcome. The question is to what degree and whether that degree will be sufficient to be clearly reflected in between-states comparisons when controlling for other factors. So yeah, it’s unlikely Vermont will have as bad of a wave, and it’s plausible this has in small part to do with vaccination rates, but there’s A LOT of other factors at play. The thing is, people do focus on vaccination rates, and governor policies, as the primary explanations.

I’m not sure we disagree with each other or with Prof S except in vague points of emphasis. But if the vaccine makes hospitalization orders of magnitude less likely, conditional on infection, I don’t see how the difference between an 85% vaccination rate and a 50% vaccination rate could play a merely small part in the number of hospitalizations we’d expect from a Delta wave. I get that taking age profiles, super-spreader events, and various other things into account could reduce or increase the expected difference. I just don’t see how, given everything we know, a 35 point difference in vaccination rates could be a small thing. If that’s your view, I think the burden of proof is on you.

Oh no I don’t think it’s a *small* thing. We absolutely agree on this. Florida remains puzzling because so many of our elderly are vaccinated. My guess is Delta is reaching pockets of unvaccinated vulnerable populations and that is enough to make it look like cases and hospitalisations are not decoupling in Florida. And/or most of the elderly were vaccinated pretty early on, so *if* immunity wanes then this might also account for what we’re seeing. All that to say, we don’t really have a clear sense of what’s going on. Facile explanations appealing to “low” vax rates in Florida just don’t hold water. They may in states like Alabama or Missouri, but even there I suspect there’s something more going on than just low vax rates.

To make it absolutely clear, I have seen thus far no reason to doubt that vaccines are very effective (albeit maybe slightly less than promised) at preventing severe illness and death.

Gotcha, I think there’s a typo in your comment (“small part” instead of “no small part”) and that’s what I was responding to.

“I don’t like the use of the term ‘skyrocketing’ [to describe the rate of increase in daily covid deaths in Florida].”

Florida’s seven-day-average covid deaths is now at an all-time high. It got here faster than it got to the peaks of previous waves.

If people are willing to use that term for states other than Florida and southern red states when that happens, then fine. Typically, however, the language then becomes very measured, cautious, euphemistic. I don’t think we need that sort of rhetoric but you do you.

(It’s also worth noting the reporting of 7-day averages in Fl has been quirky recently, leading to artificially high numbers according even to the NY Times. The numbers are bad, and comparable to previous trends, there’s no sugar coating it. But it’s best to wait a little while to make strong claims about what’s going on.)

I don’t share your view of, e.g., the language used to describe the outbreak in NYC in March 2020 or in various states in winter 2020-1. I also don’t see the harm in coarse-grained terms for distinguishing fast from slow increases in something. But I take your point about Florida data and whether we can yet say with confidence that deaths there have recently skyrocketed.

Potato, potato, it’s not a huge deal, no worries.

Getting into smaller and smaller deals, but just FYI, I read “you do you” as “you do.”

The devil’s in the details but since they don’t exist it’s no big deal.

His courage and moral commitment fascinated me, I hope that others will learn from him what it’s like to be a committed, moral and responsible person.

Imagine thinking that requiring healthy 20 year olds to take a vaccine that could otherwise go to elderly or HCWs in the developing world is going to save lives.

Especially when all the evidence coming in from high vaccination places is that the vaccine is poor at providing sterilizing immunity, and therefore at providing community protection.

That is part of my thinking too.

I think the evidence is much more complex and equivocal than that. For instance, the delta variant surged in the UK (a very high vaccination country) but then fell away again, even as it opened up. And US COVID rates correlate fairly well (though, to be sure, noisily) with low vaccine uptakes. I don’t want to commit myself to “these are because of vaccination” (cf Nicolas Delon’s wise sarcasm above) but they’ll do as illustrations that “all the evidence coming in from high vaccination places is that the vaccine is poor… at providing community protection” at the very least overstates the clarity of the signal. (I’d go further and say that the theoretical and empirical evidence is pretty good that the vaccine at least significantly reduces transmission rates, and so vaccinating young highly mobile people will indeed save lives, but that’s a longer discussion.)

I’ve looked at the data in considerably more detail than that, and I stand by the claim. In fact Pfizer has now released the efficacy data for all end points in their RCT and the effectiveness for preventing infection tout court, and infection with mild symptoms, was nowhere near the level you need to provide community protection in the long run. In one case IIRC the confidence interval included zero.

The health minister of Iceland, Francois Balloux, and several other sources I respect have reached the same conclusion.

But there is a big difference between ‘the vaccine efficacy is not enough to provide long-run community protection’ and ‘the vaccine efficacy is too low to save any lives via slowing spread’ – where we came in was your criticism of anyone thinking that lives were going to be saved by encouraging young people in the US to get vaccinated.

(If you want to say that my previous post wasn’t careful enough to distinguish the two, fair enough.)

There is also a big difference between ‘I’ve looked at the evidence in a lot of detail, and to me it now looks like the evidence is strong that we’re not going to get community protection from the vaccine, and here are some sources I respect who agree with me’ (your current post) and ‘you would have to be an idiot to support vaccinating 20-year-olds’ (your previous post.)

How does slowing spread save lives in the long run? If everyone is eventually going to be exposed to the virus?

I did not say anybody had to be an idiot, for one thing. And I said nothing about “supporting vaccinating 20 year olds.” I said something about *requiring* 20 year olds to be vaccinated. And I asked how you could believe that by taking vaccine from elderly and HCW in developing countries and mandating that it go into the arms of healthy 20 year olds, the end result could be net lives saved.

Seriously? Even if the number of lives lost is the same, people tend to prefer to die later rather than sooner. Many old people will get to die with their loved ones around them rather than inside a ventilator all alone. Also, people with comorbidities or with compromised immune systems would have longer to get well.

Then there is the simple fact that if your health care system is overloaded people that could have survived start dying due to a shortage of ICUs, ventilators, and so on. If you overload your health system you will start seeing an increase in deaths not just from covid, but from accidents and other illnesses.

The chart in this tweet shows the number of infected persons per 100k in Iceland that are vaccinated and unvaccinated. You can clearly see that the vaccine is providing protection, but also see that it is clearly not providing sufficient protection to prevent everyone, in the long run, from being exposed to the virus.

https://twitter.com/hjalli_is/status/1423251051873017859

You wrote: “Especially when all the evidence coming in from high vaccination places is that the vaccine is poor at providing sterilizing immunity, and therefore at providing community protection.”

High vaccination place alone doesn’t really tell us much since it could be a high vaccination place relative to other places. High vaccination places are also high populated places so there could be lots of *unvaccinated* people in those places as well. I would look at the overall population size and then the ratio of vaccinated:unvaccinated people to see how it compares with the infection or hospitalization rates.

For example, Maryland is a high fully vaccinated place (60.1%) and 66.7% have at least one dose according to Mayo Clinic. “High” here is relative and not ideal. Maybe 80%+ is the ideal “high.” But I’m just going by the relative use of “high” since that’s how the health officials use it currently.

It’s population is ~6 million people. This means ~33.3% of the population isn’t even vaccinated yet. That’s about ~1,980,000 people who have not been vaccinated yet.

As a result, the majority of hospitalizations/deaths were unvaccinated people. In June this year, all Covid deaths were just unvaccinated people.

So given the multiple variables and ratios involve, I‘m skeptical about your claim that vaccines being poor at sterilizing immunity. There’s more to the story here.

https://www.baltimoresun.com/coronavirus/bs-md-unvaccinated-coronavirus-deaths-maryland-june-20210707-7zugtntgifg4pomlrjy4lmjhnq-story.html?outputType=amp

It also noisily correlates with many other factors, like heavy prior infection rate/surge or prior isolation/travel restrictions. Nobody is denying that vaccines protect – the question is in what way and how, and the community protection has so far been rather elusive (long-term).

Right, but the question is ‘do vaccines protect third parties’? I took Eric’s previous post to be challenging that.

Here are the full endpoint results from the Pfizer trial on children, which were not released in the adult version:

https://twitter.com/BearGauss/status/1425658618217644033

The efficacy against asymptomatic infection, and mere symptomatic infection are both at best around 70% and at worst close to zero.

1) I’m not sure why you think this research supports skepticism. Obviously the error bars are wide here: it’s a population that just doesn’t get a lot of COVID, so on normal statistical grounds you’re going to get a noisier signal than with a more susceptible population. But there’s a fairly strong signal even for asymptomatic infection (around 50% reduction) getting successively stronger for more serious levels of infection. (And there are fairly strong cases, both theoretical and empirical, to think that asymptomatic infections spread less virus, so one can’t just leap to the assumption that it’s the asymptomatic efficacy that matters for spread reduction.)

2) I really don’t recommend getting, far less disseminating, science data based on twitter retweets. They often leave out relevant context. For instance, in this case, nothing in the tweet you link to tells you that the placebo group only has half as many members as the vaccinated group.

3) It’s the Moderna vaccine, not the Pfizer one.

(I probably won’t comment/reply further to this bit of the thread, on time grounds.)

Yes I meant moderna.

I don’t see why any of these details are especially important. You haven’t explained how a vaccine that provides even 80% effectiveness against transmissible infections will save any lives other than those of the people who receive them, in the long run.

Let alone how a jab in the arm of a healthy 20 year old American will save more lives than it would save in the arms of vulnerable people in the developing world.

Wouldn’t an 80% effective vaccine be able to get us to herd immunity? The epidemiologists I’ve heard address this issue have concluded that herd immunity seems out of reach because the vaccines and prior infection don’t produce strong enough immunity against Delta.

One reason, it seems to me, this might still be relevant is that we can’t accurately predict the course of innovation in vaccine and other technology. So who knows what it will be like in the “long run” to which we delay a person’s infection.

Unless you vaccinate more than 100% of the population, a vaccine that’s only 80% effective at preventing transmission (and it’s probably less than that) will not get you anywhere near herd immunity. Someone else can do that math for me, but that ship has sailed a long time ago.

Nobody I take seriously on these issues doubts the virus is going to become endemic at this point. Its a fantasy to think otherwise.

Yeah, that’s definitely not a claim I’d accept on faith. It could be true, but I’d need to see some kind of evidence. It doesn’t jibe with the modeling I have seen or with the degree of disagreement there’s been over the threshold required to reach herd immunity at various points in the pandemic.

I’m not saying herd immunity is achievable at this point. I’m addressing the specific claim that an 80% effective vaccine wouldn’t lower non-vaccinated people’s likelihood of being infected (no matter the degree of uptake). I’m also not seeing many scientists suggest herd immunity as a realistic goal, but the reason I’ve seen them give is that the vaccines aren’t effective enough for long enough against the Delta variant (nor is immunity acquired through natural infection). I have yet to see any epidemiologist, much less a preponderance of them, argue that a vaccine that remained 80% effective for a longer stretch of time couldn’t get us to herd immunity.

I agree this is somewhat of an academic point, given that none of the available vaccines are 80% effective for long. But then again, a lot of the points we’re discussing are academic, for example, the idea that doses foregone by healthy 20 year-olds in the US will go to people who need them. I’m all for our government vaccinating the rest of the world. But this debate about the benefits of vaccinating healthy 20 year-olds in the US has basically nothing to do with that.

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/08/10/1025463260/alabama-just-tossed-65-000-vaccines-turns-out-its-not-easy-to-donate-unused-dose

The idea that we might, in the future, have vaccines that are more effective against whatever variant is circulating is also related to a broader point, that’s not academic, about the benefits of flattening the curve. We’re thinking of “community protection” as preventing members of the community from getting at least one infection during the course of their lifetime. That’s obviously a narrow conception of community protection. So narrow that, in my view, it’s of little practical interest when deciding on the mitigation strategies under consideration here. Specifically, this narrow understanding of community protection doesn’t take account of when the infection occurs (and our state of knowledge about the virus at this point in time) nor of the total number of infections (which will correlate with the total number of hospitalizations and deaths). So if we delay the time until the virus “gets” unvaccinated person X, (a) there’s a better chance there will be better treatments by the time it gets to X and (b) X’s lifetime expected infections and, therefore, hospitalizations, etc., will be lower On the risk of hospitalization of reinfection, see this letter, particularly the final paragraph:

https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciab363/6253740

The people I know who have been hospitalized with covid or who suffer long-haul covid would think that reducing their lifetime infections would be a really good thing.

In a procrastinatory moment I played with the numbers. IANAE, etc, but on my back-of-the-envelope model, if some fraction v of the population have partial immunity (either through vaccination or from getting COVID some while back), and if the fractional efficacy of that partial immunity is e, and if r is the current r-value for the virus, then the fraction f of the population who’d have to get the virus on the current wave before exponential growth chokes off is given by

f=1- 1/(r(1-ev)).

Putting some numbers in, suppose that e=80% (I’m ignoring differences between vaccine e and past infection e; it’s a quick and dirty model) and that aspirationally we get to 90% of people being protected. Then to a good approximation,

f=1-4/r.

So if r is 4 or less, we get herd immunity straight away. If r is 8, we get herd immunity once 50% of people have caught the delta variant. And so on.

I’ve seen r0 for delta estimated as 5-9. But that’s the before-masking, before-social-distancing number. So I think we’re in a penumbral space where herd immunity might be possible or might not be, depending on exactly what you assume about vaccination rates in the fall, what the effective r ends up being for delta, how effective the vaccines are with or without boosters, and what level of protection exists from previous infection.

…which is roughly what the epidemiologists are saying, as I understand it.

People mean different things by herd immunity. But yeah, that sounds plausible. What I wrote was a bit sloppy. I should have said that vaccines alone won’t get us there. But at any rate, even if we ever hit the HIT, (1) this is going to involve natural infections (vaccines alone will likely be insufficient); (2) reinfections seem more frequent than one would have hoped (though reinfected people don’t seem to get sick twice), so it’s all gonna take more time than we thought; (3) herd immunity will not mean that the virus doesn’t spread; it will become endemic and keep coming back in (smaller) surges. The sooner we realize this the better is what I’m gathering from the most trustworthy sources that I’m following.

This excellent thread lays out the reasoning fairly clearly and succinctly.

I don’t really disagree.

Same, except that his suggestion that “people yelling for NIPs forever” has contributed to lower vaccination rates. This looks like an example of people’s “ability to draw causal inferences about extremely complex phenomena based on very shoddy data” being “magically enhanced during the pandemic.”

Yeah *I* didn’t say that and agree that that would be a bad inference. I wouldn’t be entirely surprised if that turned out to be a factor but I don’t know.

What’s fascinating to me about this whole discussion is that everyone wants to bicker with me about the claim that vaccines aren’t going to prevent everyone from eventually being exposed but nobody wants to deny either of two premises, either of which is sufficient to establish my conclusion.

This is so utterly typical of covid discussions where people only want to focus on one side of the CBA ledger.

I have no idea what CBA ledger is. But I think that, concerning 1 and 2, it’s not clear what to say. (1) seems unclear as to what it means or implies. At least for some of us, the question is not so much about being infected, but about becoming seriously ill and spreading further. I think there is some evidence at least that vaccines reduce the chances one becomes seriously ill and there is some evidence too that they can cut the transmission rate too. So even if the virus is or becomes soon endemic, this is still a big positive (just like getting vaccinated against the flu is, both in preventing one’s own sickness and from spreading it to others). I think many people think, myself included that there is still good reason to increase vaccination levels and extend it to children too, if they prove to be safe and reasonably effective. The fact that everyone will get the flu, for example, does not mean we should not try avoid spreading it. Above I have not tried to say that we should just give up on all measures (esp. in these early stage of the presence of a new disease), but merely that Delta forces reevaluation of the measures that have been in place up until now. (2) it’s true, i think, but it’s also hard to discuss. The data from Africa is odd – either we lack information or Covid has so far been relatively mild there. I don’t know. But, granting the point, it has become clear that nations first look after their own (India was a prime example, and I thought they were right to do so) and it’s hard to see this changing any time soon, even if they go about it wrongly (i.e. even if vaccinating Africa and other nations quickly is in the best interest of everyone). There are realities of politics. So although academically speaking yes, we should move the priorities, it’s probably not that obvious that’s an actionable idea as opposed to (for example) move fast on vaccinating one’s own nation to the point where it starts to be economically and politically feasible to focus on places elsewhere (some of it is already happening).

Re: 2, is that the trade-off? I.e., if the students who didn’t want to get vaccinated don’t get vaccinated, will the vaccine that would have gone to them instead go to people in the developing world?

Not snarky questions! I really don’t know what happens to our vaccine supply when people don’t use it. Does it often go to the developing world?

As for 1, from what I can tell from this comment thread, we don’t know that to be true or false. If I had to bet, I would be that 1 is true, but it seems like a lot of well-informed people read the data as more ambiguous than you’re reading it. Is there a killer link you can post that makes the case for 1? Is it the Pfizer trial?

1. In the short-term, here’s what happens to unused vaccine supply:

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/08/10/1025463260/alabama-just-tossed-65-000-vaccines-turns-out-its-not-easy-to-donate-unused-dose

2. In the long-term, we need more of this to happen:

https://khn.org/morning-breakout/pfizer-speeds-up-vaccine-production-fauci-sees-end-to-shortages/

3. What matters most is reducing suffering and death from disease. I don’t know how important eliminating spread of the virus is. (I’m open to being convinced either way.)

4. Student vaccination is merely the first point of my “5 Point Plan” ((1)-(5) above in Justin’s OP). Increasing student vaccination will have little impact on campus spread in the extremely short-term (~the next 5 weeks). What matters most for that time period is mandating high quality (e.g., N95) masks, improving ventilation (e.g., with standalone HEPA filtration machines in classrooms) and/or items (3)-(5) of the 5 Point Plan. (I guess it’s a seven-point plan now.)

I agree. My main concern lately has been about reducing the death and hospitalization rates. I have friends who are nurses telling me that the majority of hospitalizations are unvaccinated people. Vaccines in many places are still operating via appointments so many people gotta wait. The other problem is that there are millions of undocumented people who do not have appropriate IDs and can’t get one. Those people want to get vaccinated but can’t.

Wow, you guys are uncharitable readers.

My point is that in the long run, the virus is going to be endemic and spread everywhere. So, if you want to prevent suffering and death, you

(*) deliver the vaccine to people who are most likely to suffer and die if they become infected with the virus while they are unvaccinated.

Now, one could have a long argument, in which reasonable people disagree, about whether allowing countries to bid for vaccine, in the way that that the US secured its supply, was conducive to *.

But if someone has an argument that requiring 20 year olds at UAH leads to *, it has completely eluded me.

This is irrespective of facts about what happens to unused vaccine. Unused meat at the grocery store is often thrown away. There is no good argument from this to the conclusion that requiring a huge number of people who are currently vegetarians to add meat to their diets wouldn’t lead to more animal suffering.

How am I being an uncharitable reader? I literally responded to a quote of yours and I responded to Jeremy. Your comment here is a red herring. Do better, read better.

In my defense, I’m stupid, not uncharitable.

So, I think I get it now: the thought is that the more policies you have that mandate people in low-risk groups in the west getting vaccines, the less vaccine you’ll have to give to other countries, even if in this particular case the unused vaccine gets thrown away. The thought is: stop requiring this policy for the least endangered people, because that’s (possibly) a necessary condition for providing more vaccine to more endangered people. Do I have you right?

Robert Gressis: yes. exactly right.

Thanks, I understand your argument better now. The earlier stuff about “community protection” and herd immunity threw me off the scent.

Now I get the big picture but I think the meat analogy is basically hand-waving. Covid vaccines are bought and distributed totally differently from meat and the differences seem important.

I’m not an expert on this market but here’s my understanding. Governments are the biggest buyers of vaccines. Some non-profits buy them too. Governments distribute their vaccines to ensure that the most vulnerable of their citizens have the best access to them.

It seems to me to follow from the fact that the US government buys doses directly from the pharmaceutical companies that college vaccine mandates are unlikely to affect how many doses the US buys and, therefore, how this purchasing decision affects vaccine availability in other countries. I don’t see how these mandates would affect the US government’s incentives when it comes to this purchasing decision. The overwhelming political incentive seems to me to be as much American vaccination as possible. American politicians benefit, in the timeframe that matters to them, by lowering US hospitalizations and deaths.

It seems to follow from the US’ domestic distribution policies that college vaccine mandates are highly unlikely to deprive vulnerable Americans of doses.

For these reasons, the excess doses we’re throwing out are probably more of a feature than a bug, with or without college vaccine mandates, and such mandates would systematically cut into these otherwise excess doses rather than taking doses away from the vulnerable.

Obviously more could be done to ensure the vulnerable in various countries have better access to the vaccine. I’m just not convinced preventing college mandates is going to help with this.

Again, I’m not an expert on the sale or distribution of vaccines, so maybe the above will just help you identify which misunderstandings it would be helpful to dispel.

That analysis is very convenient.

And that response is a textbook example of the ad hominem fallacy.

Look, I’m persuadable on this issue. Given my acknowledged ignorance of vaccine markets, I thought I was teeing you up to elaborate on a key assumption of your argument. But playing your cards this close to your chest, at this stage of the game, makes it look like you’re bluffing.

If students get their shots, that’s great. I think Eric is just laying bare the trade-off we’re making when we’re making this a policy, in a context of limited supply, both nationally in some pockets and globally. If the goal is to save a net number of life-years in the long run, then this cost-benefit analysis is important, just like taking into account life-years lost to the impact of NPIs.

As for doses left unused, it seems like the shift should happen *upstream*. The US should redirect a (IMO, large) fraction of its stockpile to the global poor and/or to high-demand/low-supply areas in the US. Of course it’s difficult to do much with unused doses that have already been set up to be put into people’s arms. But that doesn’t mean you can’t alter the distribution chain to help those who are clearly worse off than most of us. Maybe someone can convince me that that’s structurally impossible. If so, then it turns out there’s another way in which our pandemic response is f***ing the poor. Manufacturing capacity, while not fixed, cannot be extended indefinitely, and knowledge and tech transfers are also limiting factors. So yes, it’s difficult to redistribute vaccine supply. Still, within those constraints and assuming the supply chain can be altered (nationally and/or globally), allocating vaccines to less vulnerable people is effectively depriving more vulnerable people of a chance to get vaccinated.

So I don’t know about (1) and 2. (1) doesn’t tell us anything about the possibility of redistribution upstream. (2) is from February and about increasing capacity and efficiency IN THE US. I’m sorry but it’s just gross to think more lives are going to be saved by prioritizing healthy, young Americans than doing much more than we are currently doing to accelerate the rollout in poorer countries. Even if we were to restrict ourselves to the US, the priority should be to aggressively vaccinate vulnerable populations. And I’m happy to accept the conclusion that, even though I was eager to get vaccinated, hundreds of millions of people need it more than I do.

Changing US policy so that more vulnerable people, as opposed to more Americans, would get shots would be great. What I’m not seeing is how college vaccine mandates affect the likelihood of this happening.

Feeding the hungry would be great. What I’m not seeing is how force feeding a large part of the population that doesnt need more food would leave less food for the hungry, in a situation in which there is a finite amount of food.

you aren’t being serious anymore.

“What I’m not seeing is how force feeding a large part of the population that doesnt need more food would [sic] leave less food for the hungry, in a situation in which there is a finite amount of food.”

Multiple people have given a simple model like that: the food would otherwise be thrown out. I gave a slightly less simple but still pretty simple model where that remains the case, the main consequence of which is that the same number of vaccine doses are bought for Americans regardless of whether vaccine mandates are implemented at colleges. While my model does reflect my understanding–such as it is–of how vaccine distribution works, I assumed that, if you responded at all, you would provide *some* empirical basis for thinking my model *might* be wrong in at least *one* of its details; I was expecting at least *one* empirically-informed causal mechanism connecting college vaccine mandates to vaccine availability for the vulnerable. But your substantive response is a priori economics. (And is supplemented with ad hominems and put-downs.)

(By the way, Delon seems to be saying the “distribution chain” or “supply chain” would need to be changed in order for doses that aren’t used here to go to those who need them elsewhere. At the very least, this suggests, it can’t be assumed with a high degree of confidence that the doses that would be used to meet college mandates would go to those who need vaccines elsewhere, were we to not implement college vaccines. Is he being self-serving or unserious?)

Serious–to use your term–discussions in food ethics don’t discuss food markets like that. They address causal impotence arguments by examining the empirical realities of food markets, not a priori stipulations.

Anyway, we’re going in circles now. I’m asking for empirical evidence concerning a causal link that I and, apparently, many others, honestly find dubious. You think my request is unreasonable. The most charitable assumption I can make is that we disagree about basic epistemological issues that we can’t hope to resolve here.

Have a good one.

I’m all too aware of the causal impotence objection in food ethics and I actually buy it with respect to individual consumption. But we’re arguing about national policies here, which is typically where proponents of causal impotence argue we should shift our efforts. If you think policies that affect potentially tens of thousands of students, and will then certainly apply to millions of younger adults and children, have no impact on distribution then you’re misunderstanding the import of the causal impotence objection. I’ll grant this however: it’s not entirely clear what needs to be done and what we can do to make this change, but if we can’t even discuss it we’re clearly not going to make much progress.

I appreciate the willingness to engage in good faith and, of course, agree about some of this.

My analogy to food ethics was based solely on the provision of empirical evidence in serious responses to the causal impotence objections.

So the shift to policies doesn’t matter, in my view. Policies can be, and often are, causally inert too. In this case, we’re dealing with a complex geo-political system with many actors including many powerful ones. I doubt–and at times it sounds like you do too–that we understand how efficacious US colleges, and mandates they might impose, are within this system. That seems to me to establish what I take to be a pretty modest point: we can’t know a priori what the effects of a college mandate, within this system, would be. So, to have significant credence in causal potence, here, *some* empirical evidence is required. I’m not asking for a meta-analysis of 100 top-notch studies each directly addressing the issue. Let’s just start with *something*. For example, has college policy had an effect on an US policy on an important geopolitical issue at some point in the past?

There’s another reason, besides the complexity of the system and the actors in it, why evidence is needed for the causal chain: it seems to me that the Biden administration’s incentives to buy enough vaccines to vaccinate college-age students are too powerful for college mandates to make a difference. Politicians won’t risk an avoidable vaccine shortage and will err way on the side of enough vaccines to meet demand for *everyone* who wants one. Imagine if multiple states’ ICUs were to fill up with a significant percentage of unvaccinated young adults and children (as is currently happening), and the administration didn’t get enough vaccines to meet demand amongst these populations. Do you think there’s a nearby possible world where college mandates make the difference between Biden risking this outcome or not? Maybe you think there are other scenarios where colleges impact vaccine availability without having to impact these incentives. Okay, my imagination could easily be failing me; I just want to hear what these scenarios are.

You are just making up the rules to make it come out the way you want it to. Its not just the forced consumption. If you don’t think agitating for colleges to mandate their young students to be vaccinated–after all, we are supposed to be the smart, knowledgeable, rational, well informed people in the room: college professors–contributes to a political climate in which the Biden admin is going to hoard more vaccine; push for under 12 to be approved (utterly disgraceful if you ask me); press for 3rd booster shots, etc, then I don’t know what to tell you. This the *wrong kind of moral calculus to be arguing for*. Period.

And you guys haven’t provided a modicum of evidence that making 20 year olds get vaccinated is going to save any lives. I look at this data almost constantly and I’m utterly unconvinced of this.

I think I’ve met a much higher burden of showing the policy you advocate will cost lives than you have of showing it will save any–particularly if we multiply by the relevant number of lives.

“If you don’t think agitating for colleges to mandate their young students to be vaccinated–after all, we are supposed to be the smart, knowledgeable, rational, well informed people in the room: college professors–contributes to a political climate in which the Biden admin is going to hoard more vaccine; push for under 12 to be approved (utterly disgraceful if you ask me); press for 3rd booster shots, etc, then I don’t know what to tell you.”

Okay, thanks, this is the kind of thing I was asking for: a little bit of description of the causal chain from college mandates to less access elsewhere.

However, I don’t think “contributing to a political climate” does much in this particular case. The problem is that, as I’ve been saying for a while now and as you haven’t addressed, the Biden admin will do everything you mention without college mandates, namely, hoard doses, approve the vaccine for younger children, and recommend 3rd boosters. This has been my point all along.

As for the benefits of getting younger people vaccinated, I think many people, including me, have shown that there are significant benefits to these groups themselves and to the broader community via reducing impacts on the hospital system. I don’t think you’ve addressed any of these arguments. If you won’t acknowledge they’ve even be made, I don’t know what to tell you.

Your messages are not only filled with fallacies, they’re also consistently jerkish. As Evan said, do better.

This is one of many cases during the pandemic in which it’s important to be fine-grained about causality. Just as recommending ineffectual NPIs can do more harm than good, so can recommending ineffectual approaches to reducing hoarding, in this case by causing more vaccines to go unused without succeeding in reducing hoarding. Indeed, speaking of climates, we need one of fine-grained analysis, in which opposing a given NPI on grounds of inefficacy isn’t construed as some kind of big picture political/moral stance on the pandemic, and, similarly, opposing a particular response to the problem of hoarding isn’t construed as some kind of big picture disregard of other countries.

I thought of two things.

Well, except its not like food, because we have a fixed amount of production capacity at least right now.

Yes, I recognize the difference. I was thinking about the vaccines that go into waste because of expiration. But you are absolutely right on the difference.

I have never read your work, but I respect you more than Kant, Rawls and Mill.

In solidarity,