Overlooked Originators in Philosophy

Sometimes, one person comes up with an idea, but the idea later comes to commonly be attributed to someone else. When has this happened in philosophy?

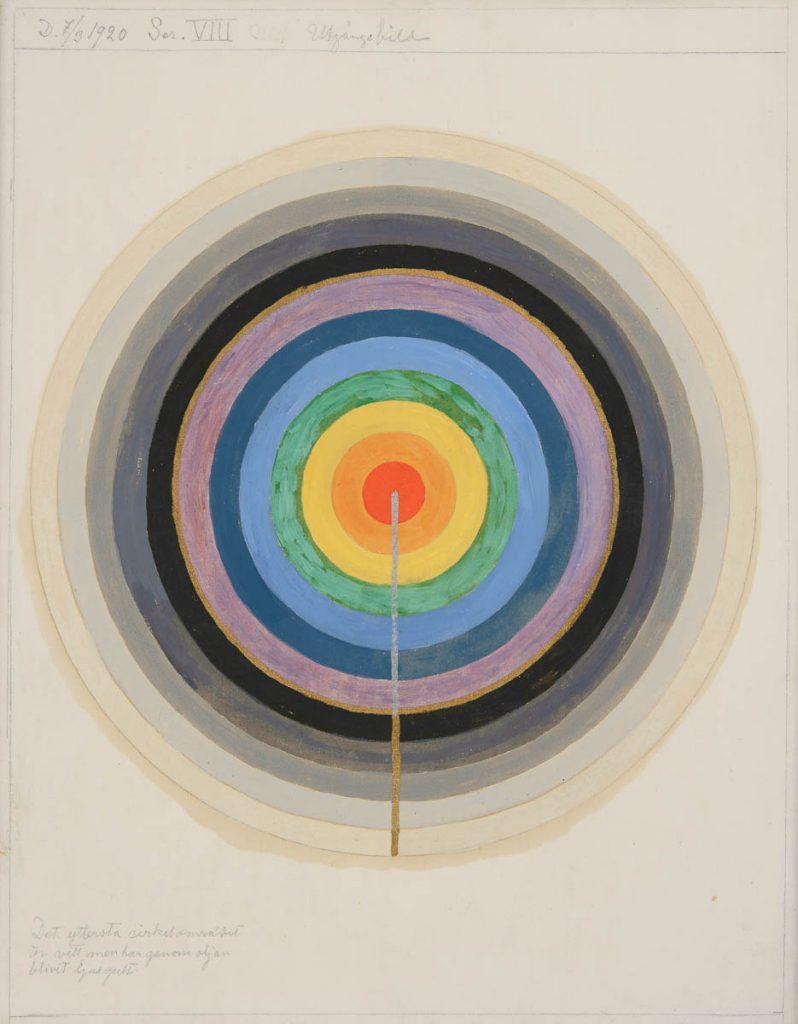

[Hilma af Klint, “Series VIII – Picture of the Starting Point”]

Take Descartes, for instance, who everyone knows as the creator of the Cogito argument. But this argument appeared in Augustine’s City of God a thousand years before. Augustine wrote: “I am certain that I am, that I know that I am, and that I love to be and to know. In the face of these truths, the quibbles of the skeptics lose their force. If they say: ‘What if you are mistaken?—well, if I am mistaken, I am. For, if one does not exist, he can by no means be mistaken. Therefore, I am, if I am mistaken. Because, therefore, I am, if I am mistaken, how can I be mistaken that I am, since it is certain that I am, if I am mistaken?'”…

Locke is often considered to be the founder of the movement because he so clearly articulated the empiricist principle. Yet reading Hobbes, I found exactly the same principle in his Leviathan: “For there is no conception in a mans mind, which hath not at first, totally, or by parts, been begotten upon the organs of Sense. The rest are derived from that Originall.” Now this might only be a coincidence, you could say. Or perhaps Augustine “anticipated” Descartes just as Hobbes “anticipated” Locke. But in both instances, we have a plausible explanation of how the later writers would have known the work of the earlier. In Locke’s case, this came to light only recently when evidence emerged proving that he had read Hobbes closely.

What are some other examples of “overlooked originators” of ideas, arguments, examples, etc., in philosophy? The examples need not be from the distant past. Perhaps there’s a misattribution gaining momentum right now that you know of, that you can mumford* by letting us know about. (And if you yourself are an overlooked originator, let’s hear the details.)

In Professor Mumford’s examples, there is the suggestion that those historically credited with the ideas were aware of where they had appeared earlier. We need not limit ourselves to cases in which we think that’s true. We have an interest in an accurate account of the origins of ideas regardless of whether misconceptions about them were introduced intentionally.

* mumford. (verb) — to correct the record of who gets credit for which philosophical idea.

There are lots of examples of this (Descartes’ argument for God in Meditation III ain’t original either!), and I look forward to seeing more in the comments… but I have a tangentially related thought.

I think it’s important to note that the whole tradition of philosophy preceding Descartes was predicated on being largely un-original. There certainly wasn’t the same value placed on being new, novel, inventive, original, groundbreaking. The approach to philosophy was rather ongoing conversation, often involving substantial regurgitation of other authors. The most creative part came in attempting to synthesize the insights that came before into a cohesive whole.

Boethius’s “Consolation of Philosophy” is hardly original. Nor is most of Aquinas. (To take one example, exactly none of his Five Ways are original to him.) Then you have Pico in the late 15th century explicitly advocating a broad synthesis of ancient Greek, Hellenistic, early/medieval Christian, medieval Jewish, medieval Islamic, Zoroastrian philosophies, and more.

For as much as Descartes waxes about his dissatisfaction with previous philosophy, or about burning everything down and starting over, he’s still very much part of this mode of philosophy. Footnotes to Plato and all that.

Gaunilo of Marmoutier (a contemporary of St. Anselm) in his ‘Liber pro insipiente’ (section 7) is subtle about the certainty of the cogito: “I know most certainly that I exist; but I know nonetheless that I am able not to exist. Moreover, I understand without any doubt that the Supreme Being, which is God, both exists and cannot not exist. However, I do not know whether, during the time when I know most certainly that I exist, I could think that I do not exist. But if I can do this, why can I not think the non-existence of whatever else I know [to exist] with the same certainty?” [Et me quoque esse certissime scio, sed et posse non esse nihilominus scio. Summum vero illud quod est, scilicet deus, et esse et non esse non posse, indubitanter intelligo. Cogitare autem me non esse, quamdiu esse certissime scio, nescio utrum possim. Sed si possum, cur non et quidquid aliud eadem certitudine scio?]

I only learned yesterday (somewhat embarrassingly, because I made this mistake in print) that Marx didn’t coin “false consciousness” – Engels coined it in a letter after Marx died.

.

Lucretius’ Spear (or at least an argument very similar to it) comes up in Aristotle’s Physics 203b20–22; 208a11–13, where it is attributed to some Pythagoreans.

Bradley’s Regress about relations comes up in Avicenna (although maybe even he didn’t originate it – he presents the argument as beloning to one party in a dispute) at Metaphysics of the Healing III, 10, 14.

One note on the Cogito example. Is Descartes really giving the same argument as Augustine? Augustine’s argument moves from ‘I doubt’ to ‘I exist’; Descartes moves from ‘I think’ to ‘I exist’. Seemingly the arguments have different premises.

For Descartes, doubting is thinking. And his argument moves from ‘I doubt’ to ‘I exist’, with the intermediate moves from ‘I doubt’ to ‘I think’, and from ‘I think’ to ‘I exist’.

In Meditations II, Descartes begins his method of doubt by supposing, believing, questioning, persuading himself, etc. He writes:

“Therefore I suppose that everything I see is false. I believe that none of what my deceitful memory represents ever existed…Is there not some God…who instills these very thoughts in me?”

He almost immediately afterward concludes that he exists, on the basis of having “these thoughts.”

A lot of foundational stuff in the philosophy of literature–from the (over)use of Sherlock Holmes cases to the notion of backgound to work on the semantics of fictional discourse–is attributed to David Lewis and (to a lesser extent) John Searle, when in fact it comes from John Woods’s book, “The Logic of Fiction”.

But that, too, may be prefigured by something else. (I’m reasonably certain not in philosophy, though!)

Perhaps you refer to John Woods’s “Truth in Fiction – Rethinking its logic”

No, that’s from 2018! The original, from 1974, is as above.

In fact, in ‘Rethinking its logic’ Woods disavows a number of te positions he initially took, notably with respect to the feasibility of using logic to model fiction.

Philosophers under the age of 50 may be unaware that there was a controversy at the 1994 APA about whether Kripke plagiarized Marcus, since I don’t think it’s been much discussed since the mid-90s. I have no idea whether those in the know regard the matter as clearly decided one way or another, but I find the Marcus side pretty compelling, and in any case it seems like even if the plagiarism charge doesn’t stick this probably is a case of his getting credit for ideas she had first.

http://linguafranca.mirror.theinfo.org/Archive/whose.html

“None of Kripke’s main ideas appears in Marcus’s 1962 paper or in anything else she published before Kripke’s 1970 lectures.”

That’s from Stephen Neale’s discussion of Quentin Smith’s APA presentation, which later came out in Synthese. Neale also says “Smith’s papers are not worthy of discussion.” I have heard the same from other philosophers of language.

Here’s one example of where Kripke innovates on Marcus. Suppose Sam = Mark. Marcus would say “Sam = Mark” is a priori knowable, since “Sam = Sam” is, and she thinks names are logically proper. Kripke, by contrast, would say “Sam = Mark” is necessary but a posteriori.

ttps://neale.commons.gc.cuny.edu/files/2014/09/Neale_Kripke.pdf

[Justin feel free to delete this reply, as on reflection I’d rather not get involved in a discussion about this. I stand by the original comment and will leave it at that.]

Neale isn’t just a friend of Kripke’s. He’s also an expert. I thought he was worth citing since you said you have “no idea whether those in the know regard the matter as clearly decided.”

[You can delete this, too, if you’d like. No desire to get into an argument here, just wanted to point out that some experts don’t buy Smith’s claims.]

I was at that APA session. It was standing room only (I was standing). By far the most dramatic and entertaining session I’ve ever been to at the APA. I scored it a 3-3 draw. Smith claimed that Kripke took 6 claims from Marcus. The commentator (Soames, I think) tried to demolish these claims, but at best succeeded in casting doubt on 3 of them (and was made to look pretty foolish with a couple of others when Smith turned the tables in his response). In talking to others after the session, I came away with the impression that Smith had persuaded a fair number, but certainly not all. I also got the impression that a lot depended on how fine-grained you wanted to be in your delineation of claims.

Ruth Marcus was in a dispute with W. V. O. Quine and Kripke entered defending Marcus. There is a 3-way discussion that you can find. Marcus had used direct reference together with substitutional quantification in her pioneering work on quantified modal logic. Quine thought is was fundamentally confused. Kripke told Quine that he was being too fast, that there was a coherent point of view here. He went on to develop it. Ruth thought that she deserved credit for being a pioneer in quantified modal logic, and in particular, in applying direct reference to it. Kripke and his defenders thought he deserved credit for getting it right. These are compatible, and arguably both true. There shouldn’t ever have been a fight and it is really a shame that it happened.

In case folx are interested, I dedicate a chapter of my “Race, Gender, and the History of Early Analytic Philosophy” to this controversy. I come down squarely on the side of Ruth Barcan Marcus. The conclusion I get to is:

“while Soames is right that Kripke cannot be accused of plagiarism, there is good reason to believe that the entire discipline should be accused of discursive injustice in its treatment of Marcus’ works. That is to say, because Marcus was a woman in a field dominated by men, her speech acts were not given the correct uptake—her expert assertions and arguments being treated as mere suggestions.”

Most of the chapter is available for free as part of the Google Books preview: books.google.com (no proxy) .

> because Marcus was a woman in a field dominated by men, her speech acts were not given the correct uptake

What evidence do you give for that claim?

I’d also like some justification for the claim that, owing to “discursive injustice”, Marcus’ work didn’t receive its “correct” uptake. I know you’ve taken yourself to have laid it out in the book, Matt (if I may), but is there anything more you could say here?

From what I understand, her work was recognized as important from the 1940s, and it’s still given that recognition today. She laid the foundations for much of quantified modal logic, and people still read her papers (some of them are real gems, offering philosophical insight into abstruse features of modal cognition). The suggestion that there was some kind of systemic “discursive injustice” RBM suffered at the hands of “a field dominated by men” appears to minimize the otherwise wide respect that she and her work have been met with. It’s not like she’s a C.S. Peirce or a C.I. Lewis or a Josiah Royce, a system-building logician who left bits and pieces only the more historically minded give much attention to today.

RBM was much more like a Frege or a Kripke, in that she blazed a trail across the philosophy of logic (in her case, with model-theoretic metalanguages for quantified modal formulae) that just about everyone else after her has marked on their own maps of the terrain. I don’t see why the internecine debate about who came up with a particular theory of meaning is revelatory of much more than that the Cult of Kripke is still with us. And Jack Samuel’s use of the term “plagiarism” doesn’t seem very helpful to me (sorry buddy — no hard feelings).

Hi Ronald and Preston,

I’m happy to answer your questions. I’ll try to be as brief as possible:

(1) Thanks for mentioning the fact that (what I take to be) the evidence is laid out in the book, Preston. This was part of the initial response I wanted to give to Ronald—and not in an obstinate, being-a-jerk kind of way. It’s just that I don’t take this to be an easy situation to break down. That’s why I wrote a 28-page chapter on it (and, really, the 29-pages of the chapter that follows my first chapter, “Discursive Injustice and the History of Analytic Philosophy: The Marcus/Kripke Case”, are part of the full defense of my argument). I also wrote this much about it because I thought it was unfortunate that folx just talked about this case in sort of quick and shallow ways. People brought it up constantly in my grad school experience (and since), always with very strong opinions, but never for long enough to try to argue for those opinions. Admittedly, some of this happens to me more as a result of the fact that I’ve sort of set Soames up as my professional foil in a lot of my published and conference work. But, I still found it odd how much people were so confidently willing to treat this as a case to have strong opinions on, but to not want to talk about in depth. Soames even suggested at the time that having anything like this discussion was unfortunate (“My task today is an unusual and not very pleasant one. I am not here to debate the adequacy of any philosophical thesis. Rather, my job is to assess claims involving credit and blame” Soames 1995, 191). Within a year of the initial session, some really big names in the field (e.g. Anscombe, Davidson, Geach, Nagel) also published a letter to the editor in the APA Proceedings stating their “dismay” due to the fact that “a session at a national APA meeting is not the proper forum in which to level ethical accusations against a member of our profession, even if the charges were plausibly defended.” Hell, the most liked comment in this discussion is the one from Brian Skyrms saying it shouldn’t have happened. Admittedly, this may have to do with the fact that Brian said a FIGHT shouldn’t have happened and I completely agree that this shouldn’t have taken on the feeling of a fight that it did.

Regardless, I find it absurd that some have suggested that anything like my conclusion or Smith’s original papers are out-of-bounds in some way. Ethics is a part of philosophy. Sessions at national APA meetings are appropriate settings within which to do philosophy. So, it seems that arguments about ethical claims like those made by Smith or myself are perfectly appropriate for national philosophy conferences. Furthermore, implicit norms on not airing dirty laundry have been responsible for perpetuating injustices over and over throughout history in every institution imaginable. Of course, it has been made clear to me repeatedly that many in our field disagree with me on this. Just recently, I gave a paper at a conference arguing that there is a pattern of problematic white feminism (with this understood not in the demographic sense of whiteness, but a conceptual or political whiteness) in the history of analytic philosophy. I was told that a conference wasn’t the place to give such arguments. I still don’t understand why that would be.

(2) So, with all of that as a caveat to why I’d really encourage folx to read chapters 1 and 2 of my book for the full argument, I can try to summarize some of what I say. For starters, the progression I take is:

[i] to argue that it is uncontroversial that a combination of 3-4 of the original 6 theses Smith associated with the new theory of reference originated with Barcan Marcus’ work

[ii] to argue that, given [i], Barcan Marcus deserves more credit than she has received.

[iii] to further argue for [ii], I looked at things like citation numbers, numbers of works anthologized, numbers of pages discussed in history texts, rankings by philosophers, etc.

[iv] to give an explanation of [ii], I focus on an abductive argument that the best explanation for her being undercited, underanthologized, undertaught, and underappreciated is sexist discursive injustice.

[v] to fill out [iv], I look at textual evidence from Barcan Marcus, Burgess, Smith, and Soames. I also look at biographical evidence from Barcan Marcus’ life and the lives of other women in and out of the field. I also consider six alternative explanations and suggest why I think sexist discursive injustice is a more plausible explanation.

Please let me know if there are particular steps in that you’d like me to expand on more in this discussion specifically.

(3) You say, Preston, that I “appea[r] to minimize the otherwise wide respect that she and her work have been met with.” It seems to me that there are at least two ways to read this. On one reading, I am minimizing the respect that she and her work have been met with (in the sense of doing something to cheapen that respect). On another reading, I am stating that the respect she has received is minimal compared to what it ought to be. I think the first reading is false, the second reading is true, and I’d defend my doing what makes the second true. With respect to the first reading, Ruth Barcan Marcus experienced a great deal of disrespect from her colleagues as a person. This was the point of the biographical evidence from [v]. As for her work, I don’t see how I’ve cheapened the respect she has received here. I agree that there has been some respect. I don’t try to hide how much there has been. In fact, I do some quasi-quantifying of that respect to try to avoid doing so. I merely say that the respect Barcan Marcus has received is nowhere near in line with what she accomplished. That brings us to the second reading I mentioned. Again, I am perfectly happy to claim that the respect she has received is minimal compared to what it ought to be. That’s what [i]-[iii] of the original chapter (as well as the chapter that follows it) were attempting to justify.

(4) You also say, Preston, that “It’s not like she’s a C.S. Peirce or a C.I. Lewis or a Josiah Royce, a system-building logician who left bits and pieces only the more historically minded give much attention to today.” For what it’s worth, my experience has been that Peirce and Lewis receive more respect and attention than Barcan Marcus. At my graduate institution (University at Buffalo), there was a C.S. Peirce Chair of American Philosophy (RIP Randy Dipert). I was also taught Peirce and Lewis in multiple classes (RIP John Corcoran). I basically took nothing but philosophy of language and logic courses in graduate school and still was never taught Barcan Marcus’ work. There is no Ruth Barcan Marcus chair in philosophy. There is no Ruth Barcan Marcus Foundation or Ruth Barcan Marcus Society. There are Peirce foundations and societies, though. Also, a quick glance at google scholar citation counts seems to confirm my feelings here. Compare Barcan Marcus (“Moral Dilemmas and Consistency” cited by 561, “Modalities and Intensional Languages” cited by 385, “Modalities: Philosophical Essays” cited by 217) to Peirce (“Collected Papers” cited by 16,444, “The Essential Peirce” cited by 3,407, “Logic as Semiotic: The Theory of Signs” cited by 1,892) to Lewis (“Mind and the World-order: Outline of a Theory of Knowledge” cited by 1,679, “A Survey of Symbolic Logic” cited by 1,312, “A Pragmatic Conception of the A Priori” cited by 229).

Even a really rough metric like space given in their Wikipedia articles seems to confirm my feelings too. Compare 2,066 words for Ruth Barcan Marcus’ entry to 18,270 words for Charles Sanders Peirce’s entry to 2,842 words for Clarence Irving Lewis’ entry. We could also include Royce on this front—whose entry comes in at 4,715 words. I left Royce out of the discussion otherwise because I know almost nothing about him. I’m only aware of him from Tommy Curry’s fantastic work arguing that “Josiah Royce was an ardent supporter of British colonization, an adamant racist, and an advocate of American empire. His proposal to colonize Black Americans in the South is an extension of this logic and is especially relevant to how one theorizes his idea of community and the consequence of such ideas on racialized groups like Black Americans today.” I’m not trying to put any support of Royce or any of that on you, Preston. Since we were talking about Royce in relation to matters of justice and injustice, I just wanted to name these facts about Royce. We philosophers are way too hesitant to recognize how much our discipline has been not only complicit with, but taken a large role in horrific white supremacist, colonial, and imperial projects. I’m so thankful for Professor Curry doing the work that he does pushing back against this trend. If folx are interested, Professor Dwight Lewis (Minnesota) and I have a conversation with Professor Curry (Edinburgh) and Professor John Youngblood (SUNY Potsdam) on some of their work at our podcast, “Larger, Freer, More Loving” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0i2F-TQGwuk .

(5) Back to things you do say, Preston, another is “I don’t see why the internecine debate about who came up with a particular theory of meaning is revelatory of much more than that the Cult of Kripke is still with us.” Again, I do feel that this debate is revelatory of more, but I don’t think that’s straight-forward. As I said, I took a book to argue for that. That said, even if it’s only revelatory of the fact that the cult of Kripke is still with us, I think that matters. Because the cult of Kripke is just one particularly stark version of what happens all over philosophy (with cults of Kant, Locke, Plato, Descartes, Wittgenstein, etc.). And, these cults have serious power in the discipline and seem to wield it nepotistically. And I think it’s telling that all of these cult figures are white men. It seems to encourage the reproduction of philosophy’s very problematic demographics. Again, if folx are interested, Dwight and I have a conversation on the reproduction of racism and ableism in the discipline of philosophy on our podcast as well. This time, it’s with Linda Martin Alcoff, Charles Mills, and Shelley Tremain. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DnOc8Gkvup4

Thanks for engaging,

Matt

Thanks Matt, this is all helpful. And I can appreciate not wanting to have to hash out something like this in a blog comment, especially if you’ve published on it. So I’m grateful that you took the time to respond.

For what it’s worth, I’m agnostic about who should receive the bulk of the credit for the ideas at issue. But I’m not sure that political conferences are places to level accusations of ethical impropriety. It sounds like you’ve found that other people in the profession feel similarly. And I’m glad to see you didn’t label anything plagiarism. But I might have been one of those people in one of your audiences. So let me try to articulate something about where that would be coming from. Make of it what you will – I’m saying this in the hope that it helps you see where someone like me is coming from, rather than as an effort to convince you I’m right.

To my mind, talk of “discursive injustice” is fine on its own, but talk of discursive injustice sounds a bit off when it’s paired to an explanation that adverts to sexism. Here I’m reminded of the accusation of “egregious levels of liberal white ignorance and discursive transmisogynistic violence” that attended the Tuvel affair, and I worry about the inflation that terms like “violence” and “injustice” are receiving in some quarters, particularly when an avowed political program is behind that inflation.

As you say, you take yourself to be offering an abductive inference to this explanation (what you call “sexist discursive injustice”) on the basis of your research. But one thing this thread illustrates is that there are lots of cases like this. What you’ve said here does an admirable job in briefly but forcefully motivating the Marcus side of what I was characterizing as an internecine fight among the Cultists of Kripke. But I’m not very optimistic that citation counts (or wordcounts) are telling us much about sexism. As with talk of “whiteness” in what you call “the reproduction of philosophy’s very problematic demographics”, the problem seems to be on the supply side, in the interests of students who choose not to pursue a career in the profession (as Morgan Thompson’s work on women in philosophy has been showing), rather than with systemic oppression at the level of the profession and its members.

Of course, perhaps both explanations have some merit. And none of this is to deny the presence of sexism or racism in the discipline, or to suppose that Barcus herself wasn’t at various points looked down on (implicitly or explicitly) for being a woman. But I’d be much more amenable to some measure of the sexism explanation if I saw more discussion of that elephant in the room.

And it sounds like your exposure to Marcus was different from mine. In my experience, modal logicians and metaphysicians seem pretty widely conversant in RBM’s work. Still, maybe there’s some “discursive injustice” if Marcus should receive the credit for a particular theory of meaning in 20th century philosophy. But I don’t see the inference to sexist/racist discursive injustice as warranted.

Finally, you say that you agree with Skyrms that the debate shouldn’t have taken on the character of a fight. But I don’t know how else to parse accusations of “discursive injustice” on the part of sexist (or racist) attitudes other than as the basis of a political conflict. And from what you said above, it sounds like you’re presenting this stuff in such a way that people in your audiences have sometimes responded with concerns about the propriety of the deed in the venue in question. Something to think about, I suppose. I’m not sure what the long arc of justice (sexist/racist, discursive, or otherwise) requires.

Thanks again for the exchange.

Completely anecdotal but as a grad student I read works by all the philosophers mentioned except for Marcus in classes on Pragmatism, Early Analytic Philosophy, Philosophy of Language, 20th Century Philosophy, Logical Theory and so on. I had never even heard of her until a blog post a couple years ago (possibly on the Daily Nous) argued that we need to pay more attention to the contributions of women in the history of analytic philosophy.

People sometimes attribute the brute facts vs. institutional facts distinction to Searle, when it’s from Anscombe’s “On Brute Facts” (1958), a portion of which was reproduced in her more famous essay “Modern Moral Philosophy” (also 1958)

Oh, here’s a biggie: Ockham didn’t originate Ockham’s Razor!

Well we don’t have to posit another philosopher to explain the origins of this principle, so by Ockham’s Razor…

Touche

Reid is famous for his Brave Officer objection to MT (Reid EIP: 276). However, the objection is not original to Reid. It appears in Berkeley’s Alciphron: or, the Minute Philosopher (1732) and Reid himself attributes the example to George Campbell. See Van Cleve (Problems from Reid 2015: 258, n20).

The idea that the mind extends beyond the skin was made famous by Andy Clark and David Chalmers in their 1998 Analysis article, “The Extended Mind.” A lot of people don’t know that Carol Rovane (1993) also proposed that the mind goes beyond our skin and that our knowledge and memory can include the contents of our journals and logs. (See pages 95–97, esp. footnote 23, of Rovane’s 1993 “Self-Reference: The Radicalization of Locke,” Journal of Philosophy, 90/2: 73–97.)

i didn’t know about this one! that footnote and the surrounding pages are definitely very much in the spirit of our article. in “the extended mind” we cited a few predecessors but not rovane. she should definitely be added to the list. thanks, catherine!

p.s. as it happens i’m returning the proofs today for a book (due out in january) with a chapter on the extended mind, so this thread came just in time for me to work in a mention of carol rovane in crediting predecessors. thanks again.

You’re welcome. That’s cool about your new book.

Speaking of minds extended, Marshall McLuhan anticipated it, for instance here:

«My main theme is the extension of the nervous system in the electric age, and thus, the complete break with five thousand years of mechanical technology. This I state over and over again.»

— Letter to Robert Fulford, 1964. Letters of Marshall McLuhan (1987), p. 30

Also, C.S. Peirce:

«A psychologist cust out a lobe of my brain […] and then, when I find I cannot express myself, he says, ‘You see, your facilty of language was localized in that lobe.’ No doubt it was; and so, if he had filched my inkstand, I should not have been able to continue my discussion until I had got another. Yea, the very thoughts would not come to me. So my faculty of discussion is equally localized in my inkstand»

— C.S. Peirce, CP, 7.366

And finally, Dewey:

«Thinking, or knowledge-getting, is far from being the armchair thing it is often supposed to be. The reason it is not an armchair thing is that it is not an event going on exclusively within the cortex or the cortex and vocal organs. It involves the explorations by which relevant data are procured and the physical analyses by which they are refined and made precise; it comprises the readings by which information is got hold of, the words which are experimented with, and the calculations by which the significance of entertained conceptions or hypotheses is elaborated. Hands and feet, apparatus and applicances of all kinds are as much a part of it as changes in the brain»

— J. Dewey, Essays in Experimental Logic (excerpt extracted from Krist Vaesen (2014) “Dewey on Extended Cognition and Epistemology” Phil Issues 24).

Rousseau is famous for his conjectural history in the Discourse Concerning the Origins of Inequality, but it owes an awful LOT to Poulain de la Barre’s conjectural history in his “On the Equality of the Two Sexes” (1673). Rousseau also seems to have lifted his line about man being born free but being everywhere in chains from Gabrielle Suchon, who uses a very similar turn of phrase to describe women’s condition in her Treatise on Ethics and Politics (1693)

I find these discussions maddening. It’s not the cogito as such, it’s the role of the cogito in his foundationalist argument which is wholly different from Augustine. It’s closer to Scotus’ use, but it’s certainly not allied to the New Science in Scotus. Descartes was quite aware that he was integrating and drawing on ideas from his predecessors in a new framework — the very title is lifted from Saint Ignatius (as well as some of the ways in which it is presented) and Augustine. Locke is very different from Hobbes, his account is not allied to and dependent on a materialist/mechanist ontology in the same way — it is an epistemic doctrine that could be satisfied by different ontological commitments.

But actually this is beside the point. “X came up with this first” is replicating the mistake that philosophical ideas are wholly distinctive and original — if they are — on the basis of the bit that can be easily summarized. And it replicates the idea of genius and originality to begin with. As Lucy Parsons said all idea have many authors, don’t confuse a copyright with originality.

This is totally fair, Aaron, as is Brian’s point that citation practices themselves are historically-situated and vary widely over times and cultures. But there are interesting cases. If Locke repeatedly denies having reading Leviathan and then we find out he has, that’s pretty interesting. And as we move closer to 20th century Anglophone philosophy, where we have a sense of what the citation practices are, there are cases where neglecting the origin of an idea is more easily attributable to possible biases. What do you think of the question of overlooked originators in these contexts?

Hi Becko! Chances are the reasons have much more to do with Locke’s political philosophy and Hobbes’ famed impiety and the associations of his politics than they do with Hobbesian epistemology. It’s interesting to think about how ideas clustered in the past differently then they do for us, for example the ways that epistemological questions were moral, religious, and political in seventeenth and eighteenth century Britain. Berkeley’s Alciphron is a great example of this.

I do certainly agree that many interesting philosophers have been forgotten, or actively buried, and one strategic way to revive them is to say that they are the real originator of a famous idea. But the problem is that this tends to cobble them to our current ways of thinking about what is important, which is underwritten by the Imperial history of philosophy which buried them to begin with, as opposed to try to actually draw out their concerns or their complexities which are often connected with issues we no longer view as philosophical — the glorious properties of tar water for example. That’s hard and is often impeded by taking philosophers and books as the basic unit of research as opposed to general problems which many philosophers and non-philosophers have takes on. But then we start to sound like intellectual historians, and the philosophers are embarrassed (not me obviously).

Suffice it to say I have far too many thoughts about this issue, hence it being a pet peeve.

What do you think?

I see it now and I’m in total agreement. It’s about “taking philosophers and books as the basic unit of research as opposed to general problems which many philosophers and non-philosophers have takes on.” Add to this “…as opposed to arguments, puzzles, distinctions, and -isms.” Thanks for the clarification. Yes, we’ll look more like intellectual historians, but as you say, we should not embarrassed by that!

Here’s a fun passage from Suchon (Preface to the Treatise on Ethics and Politics (1693). “I have not followed Seneca’s opinion in composing this book: he advises us to make the author’s identity while taking his thoughts, to hide his name while appropriating his possessions. This way of writing is frequently used at present: most learned people follow the ancient’s doctrine without revealing the sources from which they take so many fine ideas. I have never had any desire to imitate them, since the thoughts of others do not belong to me…” (The editors suggest she is referring to Seneca’s Epistle 12.11).

Just to add to this – the specific example of ‘nothing in the intellect not first in the senses’ just seems like a bad one to try and attribute to one particular ‘originator’ – it was everywhere! And had been for a long time

My initial reaction was the same as Aaron’s, but at least these discussions can introduce us to forgotten figures from the history of philosophy like Augustine of Hippo.

We should probably start by noting that what you’ve coined as Mumford-ing is actually Arnauld-ing, since (as I pointed out on Twitter), in the fourth set of Objections to the Meditations, Arnauld points out Descartes’s debt to Augustine, and in the replies to Arnauld, Descartes acknowledges the point. (Just as Hobbes points out that the first meditation doubts are not original to Descartes and etc.). So, despite the lack of uptake, this is not some well kept secret, it is merely a failure of uptake of a widely publicly available piece of information.

powell – (verb) – to correct the record of who should get credit for correcting the record of who gets credit for which philosophical idea.

Leibniz’s Law can be found in Cicero’s writings (1853, 2nd book, XVII, p. 48f)*. I stumbled across it while reading Bolzano’s notebooks who was already well aware of it. It also has been pointed out a couple of years ago by Gonzalo Rodríguez Pereyra somewhere, I believe.

The regress described in Lewis Carroll’s What the Tortoise Said to Achilles can be found in Bolzano’s Theory of Science.

In Russell’s Problems of Philosophy we have at least something very close to Gettier-cases. But about this one people have become quite aware of in the last years.

*Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1853). “Academic Questions”. In: The Academic Questions, Treatise de Finibus and Tusculan Disputations. Trans. by C. D. Yonge. London: Henry G. Bohn, pp. 1–92.

Note that one finds a version of so-called Leibniz’s Law in Aristotle’s Topics (152b25-152b29): “Speaking generally, one ought to be on the look-out for any discrepancy anywhere in any sort of predicate of each term, and in the things of which they are predicated. For all that is predicated of the one should be predicated also of the other, and of whatever the one is a predicate, the other should be a predicate as well.”!

Leibniz’s Law also occurs in Plotinus: “There can be only one first; for if there were another, the two would not differ in any way, and would resolve into one” (E 5.4.1.1-20)

Thank you, Motta and Eric! Given that Cicero had an eclectic approach to philosophy, I suspected that he was not the first. Having a clear, explicit and general formulation as early as in Aristotle surprised me, though.

Hi Jan! What I pointed out in my book on Leibniz’s Principle of Identity of Indiscernibles (page 1, fn. 1) was that Cicero attributed the *Identity of Indiscernibles* to the Stoics. I italicise this phrase because I find the use of “Leibniz’s Law” ambiguous. Sometimes it is used to refer to the Indiscernibility of Identicals, sometimes to the conjunction of the Indiscernibility of Identicals and the Identity of Indiscernibles, sometimes to a very different principle better referred to as the Substitutivity of Identicals and, much less often, to just the Identity of Indiscernibles — but it is only the latter I claimed to have been attributed to the Stoics by Cicero.

This reminds me of Marcus Arvan’s Campaign for Better Citation and Credit-Giving Practices, which you posted about in 2015 (but which doesn’t seem to have gotten off the ground, alas). https://dailynous.com/2015/03/06/credit-where-credit-is-due/

This is an example in a slightly different direction, but Buridan never discusses a donkey who is unable to decide between two equally appealing bales of hay.

“For there is no conception in a mans mind, which hath not at first, totally, or by parts, been begotten upon the organs of Sense. The rest are derived from that Originall.”

“Nihil est in intellectu quod non sit prius in sensu”, Thomas Aquinas, De veritate, q. 2 a. 3 arg. 19.

People would not attribute nearly as many innovations to the Early Modern philosophers if they read more medieval philosophy…

[Also, I’m fairly certain that by now I’m pretty infamous at logic conferences as being the person who in the Q&A raises a hand to go “well, ACTUALLY, so-and-so was already doing this sort of stuff in the 13th C. Thankfully, logicians seem to find this cool, and keep inviting me back to conferences, whereas philosophers get rather shirty when you suggest they read something written between 1000 and 1500.]

Basically everyone has just been rediscovering the distinctions and views of the medieval period for hundreds of years now.

Gettier-type cases appear in Russell (stopped clock), who is said to have known this example from Lewis Carroll. Other Gettier-type examples appear far earlier in Dharmottara’s work–see Jennifer Nagel’s discussion of whether either of these philosophers used them against JTB as Gettier does, though.

If I’d read more Indian philosophy, I could doubtless give many more examples of overlooked originators. (I do know that, for example, what Western mathematicians call “Pascal’s triangle” is in China called Yang Hui’s triangle (1200’s), but fragments of ancient Indian text from Pingala apparently discussed such triangular coefficients as early as 5th C BC.) An interesting question is the debt Pyrrhonian scepticism might owe to the Indian ‘Gymnosophists’– according to Diogenes, Pyrrho learned the practice of suspension of judgment from these Indian philosophers after a trip with Anaxarchus.

In the more contemporary examples listed, I can’t help but notice a certain trend — Carol Rovane overlooked where John Searle is cited, Ruth Barcan Marcus arguably overlooked for Saul Kripke, Anscombe overlooked (where Searle is credited). Huh. Then there is the fact that malestream analytic epistemologists mainly ignored (at best– more like actual scoffing) feminist epistemology in the 90s and suddenly discovered ‘social epistemology’ much more recently. Even now, reading Goldman and Cailin O’Connor’s SEP article on social epistemology, they mention precursors in Latour/Woolgar, Rorty, Kuhn, Foucault then bam! Goldman’s own work. How about Sandra Harding, Helen Longino, Lorraine Code, Patricia Hill Collins, Linda Alcoff?

I’m sure many of us have had the experience of reading in a recent paper a point we ourselves made twenty years earlier. Very lifelike. But I really agree with Aaron and Lisa. The idea that what made Descartes or Locke famous was one bright idea rather than what they did with ideas that had been floating around for some time is ludicrous and grounded in the great-philosopher-as-lone genius mythology which has been so dangerous to the development of philosophy.

Gilbert Harman (‘intrinsic character of experience’) and John Searle (‘intentionality’) having pioneered the intentionalist/representationalist outlook in the philosophy of perception in the 1980-90s and Anscombe’s paper on the issue (‘the intentionality of sensation’) in the 1960s. Anscombe’s paper did not come out of thin air, of course, so perhaps mostly a gripe about citation practices.

Given all the Anscombe examples above, her “Modern Moral Philosophy” argument that obligation is meaningless without God was given earlier by Schopenhauer in On the Basis of Morality (it’s a bad argument in both places).

Re Parfit: I think this is now widely known, but his repugnant conclusion was anticipated, in a single-life form, in McTaggart’s The Nature of Existence; McTaggart even said this “conclusion … may be repugnant to certain moralists” (though he himself thought we should accept it).

What’s called the Frege-Geach argument was given, against emotivism, by Ross in Foundations of Ethics. I doubt Geach knew of the Ross. He seems to have thought he knew in advance that anything written by an “Oxford Objectivist” would be wrong and so didn’t need to read it. (His “Good and Evil” claim, against Ross and others, that “good” is only attributive doesn’t mention the lengthy discussions of attributive uses of “good” in both of Ross’s books. Why not?)

I’m pretty sure Millikan invented Swampman in LTOBC before Davidson, but since she didn’t have all the superficial comic book details, Davidson gets the credit.

There’s a good case that Iamblichus discovered the number zero. Pesic, P. (2004) Plato and zero. Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal 25 (2), 1-18.

Socrates’ understanding of intellectual eros. -Diotima.

(You’re welcome!)

Robert Stalnaker is credited with the idea that a conditional, “If p then q”, is true at a world w if and only if the nearest p-world to w is a q-world. Stalnaker’s first paper on this was published in 1968. But this idea is explicitly set forth in William Todd’s 1964 paper in Philosophy of Science. Todd clearly states that in evaluating a counterfactual conditional we must consider whether the consequent is true in a world in which the antecedent holds and “is as much like the actual world as possible”. He also anticipates David Lewis’s idea (1979) that the relevant notion of similarity has to be tailored to its use in evaluating counterfactual conditionals. It’s true that Todd does not develop the idea in nearly as much formal detail as Stalnaker and Lewis. Todd was my colleague in Cincinnati until his retirement in 1996. Todd was a modest man and, although he knew that I was interested in conditionals, he did not tell me about his contribution, and I did not find out about it until I saw a reference to it in Jonathan Bennett’s 2003 book. I am not making any accusations, though. Before the internet it was extremely hard to know what had been written on a subject, and when the time is ripe two people can have the same idea independently.

I think I share some of the reservations voiced by Aaron Garrett, Margaret Atherton, and others. But I’d also like to mention that I have a forthcoming paper in which I argue that Susanna Newcome (1685-1763) played a previously unappreciated role in the development of utilitarianism and is arguably the first modern utilitarian.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/utilitas/article/abs/susanna-newcome-and-the-origins-of-utilitarianism/042A67DBD79219FF2037F0F5D324BE7F

This is really fascinating stuff Patrick.

Looks awesome.

The Descartes example is wrong. The Cogito isn’t the original element, that’s a shorthand for his innovation which was to proceed from radical doubt. The Cogito is the just the null point where doubting fails and the system is then built back up on increasingly complex arguments rooted back in analyticity. That was certainly original; it isn’t that every philosopher from Spinoza to Schopenhauer was ignorant of Augustine, it’s that his statement was part of a wholly different argument.

Proceeding from radical doubt wasn’t solely his innovation. Al-Ghazali, in “Deliverance from Error” proceeded the same way, and from the same motivation, 500 years earlier.

Reading “Geach” in one of the comments made me aware of another one:

Geach once claimed that “it took the genius of young Frege to

dissolve the monstrous and unholy union” of entertaining a proposition and judging it to be true. There is an excellent paper by Jennifer Marušić, “A Monstrous and Unholy Union” on this conflation in Locke and Arnauld.

Setting aside all of the implicit avoidance in various thinkers:it is explicitly dissolved before Frege’s “The Thought” right in the first paragraph of Meining’s “On Assumptions” from 1910, where he distinguishes in his account of assumptions between presenting (“Vorstellen”) and judging (“Urteilen”) propositions and also explicitly distinguishes between assumptions and judgements.

Frege emphasized this sort of point already 40 years before “Der Gedanke”. See the opening paragraphs of Begriffsschrift for example — this is the point carried symbolically by his distinction between the “judgment stroke” and the “content stroke”.

But anyway Bolzano was already making a similar distinction in 1837. “Es ist ein wesentlicher Unterschied zwischen dem wirklichen Urtheilen und dem bloßen Denken oder Vorstellen eines Satzes zu machen.” Etc. Wissenschaftslehre, section 34.

And who knows who might have preceded him?

Descartes began with a treatise on that his “Cogito” rescued him from then enabling him to build a theology from that singular truth. Within the book “Certainty and the Search for Absolute Truth” there is an extension to Descartes initial doubt, doubting memory and sanity that removed the basis that Decatrtes used to proceed.

The painting by Hilma af Klint is a very appropriate illustration for this thread, since she was doing this kind of abstract art about 10 years before the Delauneys and Kandinsky and other people who are better known for this kind of art. But this is far from the most impressive specimen of her oeuvre.

Thanks for noticing. As for why this particular piece of hers: for one thing, the title seemed spot on.

Oh, right! I didn’t even think about the title. And now I see how the picture might represent the spread of ideas, with a common thread remaining intact.

Is it wrong for me to believe ideas and works made famous or popularized has more to do with privilege and luck or both rather than one’s disposition. There’s just too many brilliant people that get left behind.

In the case of af Klint, I believe that in her later years she actively sought to keep her work from public view.

This reminds me of Shaughan Lavine’s invention of “McGee’s Law: Every mathematical invention is named for someone who didn’t invent it.” I believe his favorite example was Russell’s paradox.

This reminds me of “Stigler’s law of eponymy”, which states that no scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer. (Stigler attributed the law to sociologist Robert Merton.)

I read about this one in an online publication called ‘The Daily Nous’:

‘Frege “helped himself generously to Stoic logic” without ever crediting the Stoics or the author whose writings were his likely source about their ideas, according to Susanne Bobzien, professor of philosophy at Oxford University.’

From: “Did Frege Plagiarize the Stoics?”

By Justin Weinberg (February 3, 2021)

https://dailynous.com/2021/02/03/frege-plagiarize-stoics/

Some person named C.E. Emmer noted in the comments that the source can be accessed for free:

“The University of London does provide an open access (free) PDF of the book in which the essay appears,” he wrote.

https://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/keeling-lecturesRepor

I doubt that Putnam – or anyone else – has ever claimed credit for being the originator of the Brain-in-a-vat scenario (which is obviously just a variation of Descartes’ evil demon hypothesis), but I was amused to find a very similar scenario to the one Putnam describes in “Reason, Truth in History” in the notes of a lecture series by Sellars edited by Pedro Amaral and published as “The Metaphysics of Epistemology”. Here’s a short excerpt of the passage I am referring to: “Take the modern form of this line of thought. An old, mad scientist anesthetizes people, excises their brains and sensory nerves (efferent and afferent motor nerves) and puts them in test tubes and keeps them healthy. There they are! on the wall. You can see the jars. He has cut the brain, and the blood is being pumped in with the right amount of nutrient. There are 20 or so lined up. Suppose he has over in one corner of the lab a fantastic electronic device with keyboards of various kinds-you know the story-and the sensory nerves are hooked up to the electronic system. […|” Sellars himself calls it “the science fiction version of Descartes’ demon” a couple of lines later. The lectures were given in 1975 but appeared in print only years later. It seems like this way of presenting Descartes’ skeptical hypothesis was just somehow common around that time (Putnams “Reason, Truth and History” was published in 1981). At any rate, I don’t mean to imply that any sort of plagiarism occurred…I will just not call Putnam “the originator of the BIV-scenario” anymore. And I’d be curious to know if there is a common source for Putnam and Sellars (besides Descartes of course…I am rather thinking of some actual work of Science fiction for example).

Putnam never claims to originate the brain-in-vat scenario. On the contrary, he introduces his discussion of it with the sentence “Here is a science fiction possibility discussed by philosophers.” (Reason, Truth and History, p. 5)

Speaking of Putnam, let me mention that what is universally called “Yablo’s Paradox” (published by Steve Yablo in 1985) was completely laid out in a lecture by Putnam in his logic class in 1966 (it’s in my class notes). As far as I know, though, Putnam never published anything on it.

That’s neat. Did you let Steve know? It’d be useful to have your notes published (in the way that Dunn published his famous “formal and natural languages” conference paper — viz., his website. The “Putnam-Yablo paradox” still attracts various applications, so citing the “Goldfarb’s Putnam notes” would be good!

OMG!!! I had no idea Putnam came up with it. Albert Visser had a closely analogous paradox. We discussed at Stanford in 1985 or so at a conference Feferman organized; Vann McGee was there too and Hans Kamp. I think I didn’t quite follow what Albert was saying which led to not acknowledging him properly. (Some do speak of the Visser-Yablo paradox.) Kripke talks about these issues in a 2019 paper “Ungroundedness in Tarskian Languages.” Burgess once suggested to me that Kripke had presented a similar paradox in a Princeton seminar way back when.

PS I remember Robert Solovay saying in a Berkeley logic class in the 1980s that a convention had arisen of attributing results to whoever proved them after Godel lest everything be called Godel’s theorem.

Did Visser publish his conference paper? Or does he still have a copy? (Again, as with Mike Dunn’s paper, it can be valuable just to throw it up on one’s website.)

…lest everything be called ‘Gödel’s theorem’ indeed.

It’s in Visser, “Semantics and the Liar Paradox,” Gabbay and Guenthner (ed) Handbook of Philosophical Logic (1989), p638.

Bewdy. Thanks, Steve.

jonathan harrison’s wonderful 1967 aristotelian society short story/article “a philosopher’s nightmare”(https://philpapers.org/rec/HARXPN) is a neglected classic in the brain-in-vat genre.

This is great!

Almost as early as Harrison’s paper, there is Stanislaw Lem’s brain in a vat story in Memoirs of a Space Traveler: Further Reminisces of Ijon Tichy, originally written in 1971. Though it is more brains in boxes than in vats.

As with all of these, one could argue about the similarities/ dissimilarities. But Harsanyi (Cardinal Utility in Welfare Economics and in the Theory of Risk-taking” 1953) discusses a notion of the veil of ignorance before Rawls. Here’s a quote:

“A value judgment of the distribution of income would show the required impersonality to the highest degree if the person who made this judgment had to choose a particular income distribution in complete ignorance of what his own relative position (and the position of those near to his heart) would be within the system chosen.”

A while back I heard there is some small library (in Canada?) that received the part of Rawls’ library that was devoted to economics, which would include his copies of Harsanyi (at the time his library was being donated, these materials apparently were not seen as desirable). I hear his marginal notes are there in many of the books. Not sure if Rawls scholars have really delved too deeply into those holdings. Anyone know more details / if I heard that right?

I can’t answer that question, but thought I’d note that Forrester in In the Shadow of Justice (pp. 12ff.) discusses Rawls’s interest in Frank Knight’s The Ethics of Competition (1935) (Knight was a noted Chicago School economist). Forrester used Rawls’s papers at Harvard, among other sources, but I don’t think there’s any mention of a Canadian library in her endnotes.

The Harsanyi paper is widely known and cited in A Theory of Justice. What is lesser known is that Harsanyi wasn’t the first economist to come up with the idea. William Vickrey, in a paper from 1945, refers to the idea that the distribution of income in society should follow the choice of an individual who does not know his position in society. (“Measuring Marginal Utility by Reactions to Risk,” Econometrica 13 (1945): 319-33.)

What about Hume’s bundle theory of the self being anticipated and richly developed by Buddhists 2,000 years earlier (ie anatta or “not-self”)?

This is getting a bit silly. The point is not to just identify similar ideas. The point is identify ideas that may have influenced another, but where credit or influence has not been acknowledged.

That’s a fair point. However, Mark appears to simply be asking a question. Furthermore, Hume is believed to have traveled to parts of the world where these Buddhist ideas were being circulated, and even to have sought to discuss philosophy there. So, it’s not charitable to interpret Mark’s comment as simply pointing out similar ideas. It is better to interpret it as asking whether and to what extent the bundle theory might be influenced by similar Buddhist ideas. Someone who knows might be willing to offer an answer.

I wonder whether Hume’s ideas about induction might have been influenced by the Buddhist ideas about universal concurrence (e.g., of fire with smoke) that were discussed in India long before Hume. (For a prominent example, see the work of the Indian philosopher Dharmakīrti.)

Perhaps I misunderstood the intent of the article. I’ve heard theories that Hume was influenced by Buddhist ideas in some direct or indirect ways but I’m not an expert in that so can’t evaluate it.

Still, it seems especially important to try to identify the origins of ideas that reappear throughout history in various forms, regardless of whether the people who developed them later were influenced by those who came before. Imagine thinking that Hume was the first philosopher to come up with the idea of the bundle theory of self? That would indicate a serious knowledge gap in the history of philosophy. I’m sure there are many other such examples. And since Buddhist and other Asian philosophy has been and continues to be relatively marginalized in philosophy, it seems worth looking at. After all, the title of the article is “Overlooked Originators in Philosophy”.

My two cents anyway.

Old news (conjecture) at this point, Gopnik has a paper on it: https://philpapers.org/rec/GOPCDH-4

Probably various philosophers borrow from classical sources and then subtly disguise their tracks.

What did Taylor Swift say to the ancient Greek doctor? “She doesn’t get your humors like I do.”

Descartes seems deeply misunderstood here.

By his own account, Descartes spent much more time working on what we today would call science than on metaphysics. And his contemporaries saw him the same way. The method he introduced was a method of careful reasoning that would allow the thinker to understand the world without “the useless lumber of scholastic entities.”

In 1633, just as he was preparing to publish the beginning of the first part of his major work (which was on science, not metaphysics), Galileo was condemned. As a Catholic, he had to advance very guardedly, especially since heliocentrism was at the core of much of _The World_. He therefore decided to publish a shorter version of his scientific work, together with an accompanying essay on the method he used to arrive at his conclusions. This new work, the _Discourse on the Method_, explained quite clearly his method of reasoning. In one chapter, he tried to show how his method of reasoning could be used even to demonstrate that God exists and that the soul is distinct from the body, without depending on Aristotle’s conclusions. This demonstration was, presumably, meant to help dispel the view that his new, independent method of reasoning would not lead people into atheism, despite the fears of many at the time that the new science was pushing in that direction.

But it is clear that Descartes’ method of reasoning did not centrally involve a grappling with radical skepticism — how could it, when the majority of the _Discourse on the Method_ dealt with the sciences? But that is not the _Discourse_ most of us encounter in our philosophy classes. Those versions have only the introductory essay, with the sections on optics, geometry and meteorology removed, thus obscuring the purpose of the work.

A few years later, finding that the charges of irreligiosity persisted, Descartes wrote the _Meditations_ to emphasize even more strongly that his new method of reasoning (which did not entail that all proper thinking be a priori, despite the later misrepresentations, which were based on an incorrect extrapolation from a reading of just the _Meditations_) would only confirm what he saw as the truth of religion. But as Descartes made clear, he saw these metaphysical arguments as worth thinking about only once in one’s life. It was empirical science and mathematics that he mostly aimed to illuminate through his method of reasoning.

The great innovation of Descartes, as he himself saw it and as his contemporaries saw it, lay in the elucidation of a new scientific method. It was for this that Descartes was originally recognized as one of the great philosophers of his day. Much later, when the term ‘philosophy’ had become much more limited, certain historians with simplistic and systematic projects seem to have assumed that Descartes’ importance rested on the _Meditations_. And so it is that generations of philosophy students are incorrectly taught that Descartes’ main innovation is the ‘cogito’. But as far as I recall, Descartes nowhere suggests that this is true or even that the ‘cogito’ was his own invention.

This comment is so true. When I was in graduate school, I had to read something in Descartes’ optics for a project and went to another library to find the “full” Discourse on Method. For the first time I read the Discourse with the sections on optics, geometry and meteorology (I recall a discussion of the rainbow!). It put Descartes in a whole different light and corresponds to Justin K’s take on this. Thank you.

Hume on necessary connections (Berkeley got there first)

Actually I think you can find that argument in the Cartesian occasionalists like Malbranche and others whom Hume probably had read. Nor was it novel in them, it originates in the Muslim philosopher Al Ghazali who used it to defend occasionalism against Muslim Aristotelians.

In the XX century the verifiability of a scientific theory was considered and eventually, with K Popper, assumed not to be possible.

Approximately in 1270, St Thomas Aquinas in the comment to De coelo et mundo (On Heavens) by Aristoteles, Liber 2, lectio 17, no 2:

“ [St Thomas has listed the cosmological theories known to him. Next: ] Illorum tamen suppositiones quas adinvenerunt, non est necessarium esse veras: licet enim, talibus suppositionibus factis, apparentia salvarentur, non tamen oportet dicere has suppositiones esse veras; quia forte secundum aliquem alium modum, nondum ab hominibus comprehensum, apparentia circa stellas salvantur.

The hypotheses found by them are not necessarily true: even though the phenomena might be explained under these hypotheses, it is not admissible to consider such hypotheses as true because perhaps the phenomena of the stars can be explained in some other way not yet known.

and in the Summa Theologiae (Summary of Theology) I pars, q. 32, a. 1, ad 2

Alio modo inducitur ratio, non quae sufficienter probet radicem, sed quae radici iam positae ostendat congruere consequentes effectus, sicut in astrologia ponitur ratio excentricorum et epicyclorum ex hoc quod, hac positione facta, possunt salvari apparentia sensibilia circa motus caelestes, non tamen ratio haec est sufficienter probans, quia etiam forte alia positione facta salvari possent.

Reason is otherwise used not as to give a sufficient condition to prove an hypothesis but in order to give agreement between the hypothesis and the resulting facts, in the same way as in astronomy eccentrics and epicycles are introduced because with such hypothesis the observed phenomena of the heavenly motions can be explained; but this is not enough in order that sufficiency is proven [for the hypothesis to hold], because the phenomena might be explained with some other hypothesis.

I hope that my translation is effective as I am neither a native English speaker nor a phylosopher, but a mathematical physicist.

I think Thales is often given too much credit for allegedly spearheading the idea that ‘water’ is of important philosophical significance. The rather derivative work of Thales (born 624 BCE or 620 BCE) is predated by well over a thousand years by the pseudonymous Babylonian authors of the notably water-centric Epic of Gilgamesh (earliest versions of which appeared in 2100 BCE). A scandal!

This is mostly fair, but I feel you are giving too much credit to the Babylonians here, even if you are right to point out that Thales’ extolment of water is non-original. You see, the Babylonians themselves, even in the third millennium BC, were themselves deeply indebted to much earlier scholarship on water, not least the inscriptions on the The Narmer Palette, also known as the Great Hierakonpolis Palette, which dates to the 31st century BC, and which denotes early hieroglyphic representations of water, signifying its importance, that would have been well-known by the authors of Gilgamesh.

And even before that it’s a turtle. And then more turtles.

Nelson Goodman is usually given credit for a bunch of arguments against the resemblance theory of depiction, especially logical considerations (e.g. resemblance is symmetrical, depiction is not)— from Languages of Art, 1968. Many of these arguments show up in Arthur Bierman’s “That there are no iconic signs”, 1962 in PPR.