Did Frege Plagiarize the Stoics?

Frege “helped himself generously to Stoic logic” without ever crediting the Stoics or the author whose writings were his likely source about their ideas, according to Susanne Bobzien, professor of philosophy at Oxford University.

She makes the case in “Frege Plagiarized the Stoics,” a chapter in the 2021 edited collection, Themes in Plato, Aristotle, and Hellenistic Philosophy: Keeling Lectures 2011-18.

Bobzien argues that Carl Frantl’s Geschichte der Logik im Abendland was Frege’s source for the Stoic ideas he borrowed.

Professor Bobzien provides substantial textual evidence of remarkable similarities between Frege’s writing and the ideas of the Stoics, as presented in Carl Prantl’s 1855 4-volume Geschichte der Logik im Abendland (History of Western Logic). She writes:

No single textual parallel validates the thesis of plagiarism. It is by accruing passage by passage, sentence by sentence, phrase by phrase, the Stoic elements in Frege’s oeuvre, organizing them by (Stoic) topic, and considering their philosophical significance (and adding to this the historical data provided above) that a compelling case is built. Taking in the result requires patience on the part of the reader. Those who are less interested in the philosophical implications of the parallels can directly consult the tables with synopses added for each topic in order to facilitate absorption of the semblances at a glance.

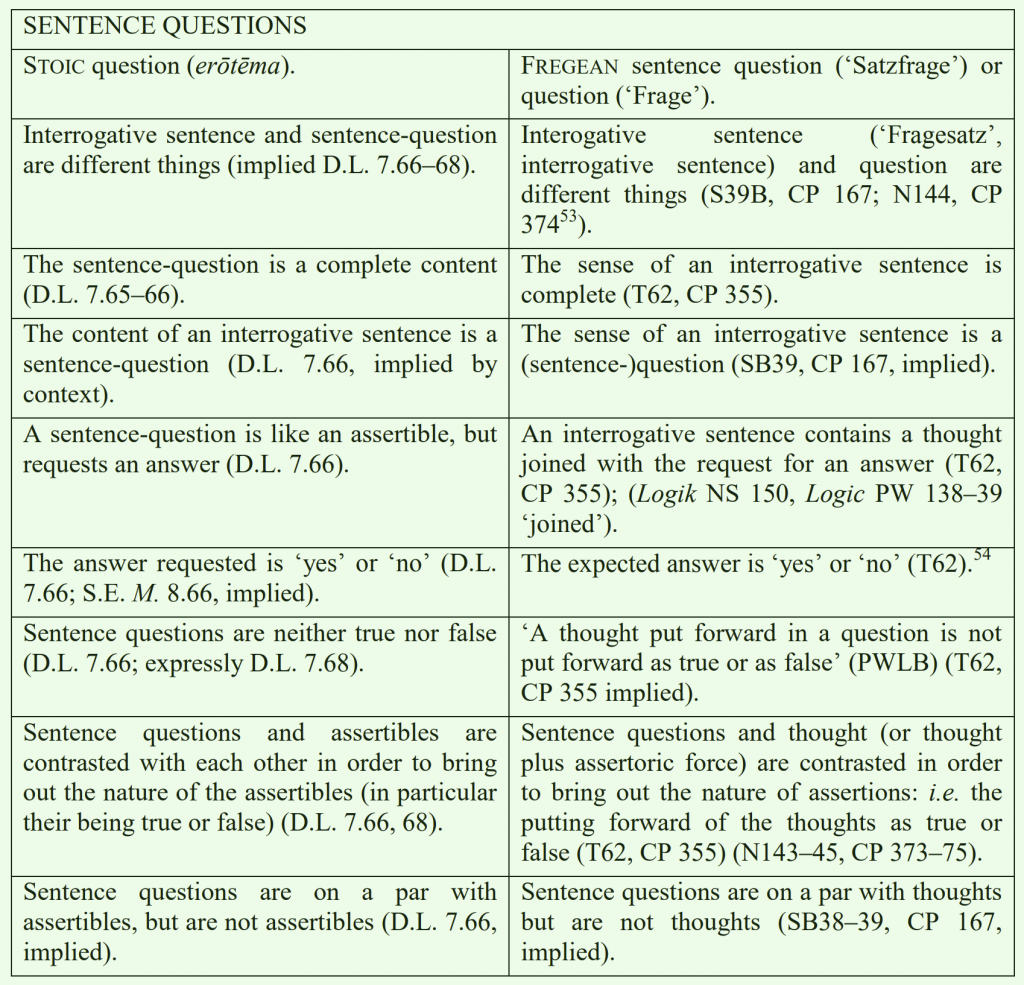

I reproduce two of those tables below as examples. All told, she counts up at least 120 “parallels” between Stoic ideas and Frege’s writings. Professor Bobzien adds to this collection of parallels three other lines of argument to support her conclusion that Frege plagiarized the Stoics by way of Frantl:

First, it is vastly more likely that Frege obtained his knowledge of Stoic logic from one text, rather than from browsing through the dozens of Greek and Latin works with testimonies on Stoic logic that Prantl brings together. (Of the hundreds of Stoic logical works, not one has survived in its entirety and we are almost completely dependent on later ancient sources.) Second, virtually all parallels between Stoics and Frege are present in Prantl, and some important elements of Stoic logic without parallels in Frege are missing in Prantl… Third, there are several misunderstandings or distortions of Stoic logic in Prantl which do have parallels in Frege.

Here are two of the many tables of textual similarities Professor Bobzien assembled. The Stoic ideas are in the left column, Frege’s are in the right. (You’ll have to consult pages 72-74 of the chapter manuscript for the abbreviations.) This table concerns sentence questions:

This one concerns universality:

Professor Bobzien doesn’t come to any conclusions about whether Frege’s plagiarism, if it is that, was intentional. She considers several possibilities in the conclusion to her chapter. She even considers the possibility that, “against all odds, Frege did not draw on Stoic logic”:

Then we have the following immensely fascinating situation. Separated by over two millennia, we witness logicians who started (a) with the same general idea of content that—in some sense at least—exists independently of our saying or thinking it, and (b) with the same general conception of a propositional logic. These logicians were then confronted by the same set of problems: problems regarding how linguistic expressions can serve us to express and communicate that imperceptible content and can explain the complexity of content (especially as it is required for reasoning); how for this purpose natural language expressions may fall short in several ways: in particular how they may contain too much or too little or the wrong expressions, and how they may not provide the means to unambiguously express content of potentially unlimited complexity. In this case, independently of each other, both the Stoics and Frege would have thoroughly considered all four issues, and in doing so would have followed staggeringly similar pathways.

Immensely fascinating indeed.

This is totally fascinating! My first project (“Sentences, Senses and States of Affairs”) after my PhD in 2001 was on the transmission of Peter Abelard’s dictum theory (which is often claimed to be derived from the Stoic lekton theory via Augustine’s talk of the dicibile) to the 14th and then to the late 19th and 20th centuries.

What was striking was that the theory seemed have dissappeared in the meantime, and there were no convincing texts to be found that allowed for connecting the dots to the 20th century. NEVER would I have thought that Frege might have just copied the Stoics.

That is indeed immensely fascinating! Lamely, I cannot resist pointing out that this question of the nature of Frege’s relation to the Stoics could be called the Fregefrage 🙂

Frege still deserves credit for developing a rigorous formalism of predicate logic.

This point has been made, almost 50 years ago, by Gabriël Nuchelmans in Theories of the Proposition. Ancient and Medieval Conceptions of the Bearers of Truth and Falsity, North-Holland, Amsterdan/London 1973, ISBN 0-7204-6188-X.

Good philosophers copy. Great philosophers steal.

In response to Menno Lievers: Nuchelmans has one paragraph, p. 85, section 5.2.2, in which he refers to an 8 page comparison of Frege’s Sinn and Gedanke to the Stoics’ lekta and axiomata in Mates, Stoic Logic (1961). This is an aside in Nuchelmans who is concerned to argue that Stoic lekta and axiomata, unlike Fregean Sinne and Gedanke, do *not* exist independently of thought in “a sort of Platonic third world,” rather “they exist only in so far as they are thought and expressed in words.” (p. 86) That is, Nuchelmans is arguing against the parallelism, not for it.

Mates, however, does make some of the comparisons argued for by Bobzien, but without attributing influence, and in the midst of a discussion not only of Frege but also Carnap. And Bobzien cites Mates on this. But her paper is 80 pages long, and covers much more than Mates. Clearly it deserves careful study, which I have not yet had time for!

In response to Michael Kremer: Nuchelmans did emphasise, if not in this book, then certainly in his lectures on assertion and later works, that there are strong affinities between the Stoic analysis of assertion and that of Frege. These do not concern the issue of the ontological status of lekta versus the ontological status of Gedanke, but the act of judging. Instead of assigning the assertoric force to the copula, the Stoics, just like Frege, separated the act of judging form the judgeable content (lekta, Gedanke). Nuchelmans also frequently referred to ancient and medieval philosophers who gave a bi-partite, instead of tripartite analysis of the content of an assertion (lekton, Gedanke). Given the provocative title of professor Bobzien’s article, it seems only fair to pay tribute to a pionier in the field, who has not received the recognition he deserves.

Responding to Menno Lievers: I think no one seriously working in this field, understimates the indeed pioneering works of Gabriel Nuchelmans. However, Nuchelman’s and Bobzien’s contributions are quite different: Nuchelman’s and others noticed striking conceptual similarities, but only Bobzien has made the directly historical case that Frege drew on and took over the Stoics via Prantl, without acknowledgement. That discovery is nothing short of a sensation, and a real game changer for the history of logic and semantics.

What is the probability of finding a few similarities in texts that deal with a similar topic? I would think it is very high, but I have no idea… Without some sort of measurements I’m not sure this is a very fruitful exercise. That is, we have no way to say if 120 parallels is high or low. Moreover, while some of the given examples are fairly similar, others are not, and some are just similar because they are so brief.

The presentation here is quite misleading. If one read the comparison table, which visually really stands out, one gets the sense that Frege copied almost word for word from the Stoics. But the table is just a summary by Prof. Bobzien of their ideas — some of them not even explicitly stated in the original but only implied by context. Now that’s not to say anything about the merits of Prof. Bobzien’s arguments, only about the presentation here.

By the way, some of the similarities are very superficial. Take the “Sentence Questions” table for example. That there is a difference between interrogative sentences and questions, that questions require answers, that (polar) questions require ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers, that questions are not true or false, and that by saying ‘yes’ a speaker expresses the same proposition associated with the question — these are all platitudes that anyone who reflects for a few moments on the topic will come to realize. They are also all part of contemporary linguistic theories of questions and no one credits Frege (or the Stoics for that matter) for them.

I think people should read the conclusion of Bobzien’s article, where she contextualizes the concern about plagiarism. There are several options she considers with varying degrees of severity. I don’t have a settled view of the matter but think it would be good to be mindful that there are some questions here about how to interpret this and just what it means.

Unsurprisingly, given the rest of their philosophy, the stoics didn’t feel the need to complain.

FWIW, here is a brief response to the paper and some initial reactions: https://handlingideas.blog/2021/02/05/the-stoic-foundations-of-analytic-philosophy-on-susanne-bobziens-groundbreaking-discovery-in-frege-and-prantl/

In my view, ehz is right that some of the comparisions may seem somewhat superficial, at least prima facie. What is worse, at least some seem sloppy with regard to Frege’s work and also misrepresent his positions.

As to sloppiness: Take the list about questions. Frege carefully distinguishes between yes-no questions, e.g.: Did you do it?, and wh-questions, e.g.: Who did this? The list above says he holds that questions require a yes or no as answer. That only applies to the first sort of questions he distinguishes. However, some of the references in the list concern passages in which he discusses wh-questions. This is an odd mismatch of topics and references.

And the point actually results in a wrong representation of Frege’s views. Frege takes a yes-no question to express an ordinary thought. For him, “Did you do it?” expresses the same thought as “You did it”. He thinks the difference between the two sentences is *not* located at the leven of content, but on what nowadays would be called speech-act level (speakers do something different with the same content).

With that in mind, take a look at the table again. At the same time, it is said that Frege takes questions to require yes and no answers and that he distinguishes between a thought and the content of question (last entry of the list). But it is precisely the case of yes-no questions in which Frege *identifies* the content of a question with a thought.

I conclude that the table of comparisons concerning questions is, as it stands, quite dubious. Not only are the comparisons somewhat superficial; the presentations of Frege’s views are distorted and sometimes simply wrong (and one may of course be afraid this was done in order to find more “similarities”).

I do not know whether this cluster of comparisons with respect to question is representative for the quality of the comparisons in Bobzien’s whole article. But this case alone should certainly raise some doubts about the whole thing; and before we declare this a fascinating find, we should test the premises on which it is built. If they are, on average, not stronger than the case about questions, then the find does not hold up to scrutiny.

Replying to Ben. There might be those who’ve read what you’ve had to say (some even who’ve given it a thumbs-up) and who suppose that you’ve responded to Bobzien’s paper. But evidently you have not read it. Despite this, you see fit to say that its table of comparisons is “dubious”, that the paper is “sloppy” and “superficial”, and that it distorts and misrepresents Frege’s views. These are preposterous judgments. I’ll comment now only on your three specific charges.

1. You suggest that Bobzien fails to appreciate that Frege distinguished between Yes/No questions and Wh?-questions. To see that this suggestion is false, see her III.1.2.3 in which Bobzien says ‘‘Both parties [sc. Stoics and Frege] distinguish between what Frege calls word-questions and sentence-questions. (I can only think you looked at the table at the end of III.1.2.3 and failed to see that that table concerned only sentence questions.)

2. You accuse Bobzien of misrepresenting Frege’s views, saying that for Frege ‘You did it’ and ‘Did you do it?’ express the same thought. In fact Bobzien shows, using quotations from Frege (and supplying the original German in fnotes) that Frege presents (at different times) two views of sentence questions, in the first instance taking force to belong in the sentence question.

3. You complain that Bobzien should say that Frege takes questions to require yes and no answers, and that he distinguishes between a thought and the content of a question. ‘But’, you say, ‘it is precisely the case of yes-no questions in which Frege *identifies* the content of a question with a thought.’ No doubt you confine yourself to what you yourself know of Frege’s later work. Bobzien considers earlier and later work, meaning to provide evidence for her hypothesis that Frege acquainted himself with Stoic logic by reading Prantl.

In your final paragraph you generalize from the specific claims you falsely attribute to Bobzien to the conclusion that “we should test the premises on which [the entire paper] is built”. Indeed we should –you included. It might be that if you were to test the paper’s actual premises and follow its argument, you would be led to retract your comment.

Hi Jennifer, there seems to be some misunderstanding here. I was talking about the list of comparisons provided by Justin, as did some other comments before mine. Some commentators found, based on these samples, that a fascinating discovery has been made. What I tried to say is that *the samples presented here* do not convince me this is so.

However, I did not claim no such discovery has been made. In fact, I did not intend to make general claims about Bobzien’s whole paper. I tried to express that in my first paragraph, and I explicitly opened my last paragraph with “I do not know whether this cluster of comparisons with respect to question is representative for the quality of the comparisons in Bobzien’s whole article.“ I wrote this because I had not read the paper, but only joined the discussion of the excerpts presented here. I am sorry if this wasn’t clear enough. Still, given my remark I just quoted, I do find some things you write about what I said somewhat uncharitable.

Also, it is of course excellent if Bobzien provides much more context and explication in her paper. That doesn’t change, however, that the table with the comparisons above seems misleading to me, for the reasons given. E.g. the 6th entry indicates that the table is concerned only with yes/no questions, since it generally says these are the expected answers; but the first reference in the last entry, given to support that Frege distinguishes the content of a question for that of the corresponding assertoric sentence concerns a passage in SB in which Frege does not speak about yes/no questions but about wh-questions. And one can certainly maintain that “who did it” does not express a thought that is true or false while at the same time holding that “ did you do it.” does — which is a combination of views Frege held (at least in some works).

But, as I said, all of this concerns only the table presented above. And while I said before that I don’t know whether this is representative on the paper, I am happy to believe you that it is not.

OK., Ben. I suppose I was questioning your assumption, which you now make more or less explicit, that the Table of Comparisons, considered in isolation from the textual evidence and argument of Bobzien’s 80 page paper, might be taken to be “representative”. It seemed that you thought that one could start to answer the question whether we had a ‘fascinating find’ without considering any of Bobzien’s findings of fact, her argument, and her knowledge (displayed through quotations) of Prantl and of Frege’s early work.

Myself, I meant to question whether one could “raise doubts about the whole thing” (as you put it) by attributing claims to Bobzien that she not only doesn’t make but actually controverts. (Thus my points 1., 2., 3.)

You spoke of “commentators [who] found, based on these samples, that a fascinating discovery has been made”. I’d guess that the commentators who said this based their judgment also on Bobzien’s reputation as a careful scholar, and that they would have assumed that she wouldn’t have distorted and misrepresented Frege—certainly not in order to make her case.

Ben, looks to me like in your initial comment you trash an 80 page paper and its author based on three inaccurate claims after having read a one page quotation of the paper. Dunno, but Hornsby seems about right in what she says.

Hi Nate, as I explained, my intention was neither to trash the author, nor to deny the paper’s claim. I only explained why *the excerpts presented here* do not suffice to make me think there is a fascinating find here. Whether the paper’s claim is correct or not, I tried to say, would have to be judged by a thorough appreciation of the whole paper (see the last paragraph of my comment).

But as I realize from Jennifer’s and your comment, this came across wrongly, and I said I am sorry if my post wasn’t clear enough; I am happy to say it again. And if this whole thread was meant to be a discussion between people who studied the paper, I mistook the nature of the conversation and thus contributed where I shouldn’t have.

The University of London does provide an open access (free) PDF of the book in which the essay appears:

https://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/keeling-lectures

Many other examples of such precursors can be found in this post and its comment thread:

“Overlooked Originators in Philosophy”

By Justin Weinberg. July 26, 2021

https://dailynous.com/2021/07/26/overlooked-originators-philosophy/