Intuitive Expertise in Moral Judgments (guest post)

“People’s intuitive judgments about thought experiment cases are influenced by all kinds of irrelevant factors… [and] the issue of intuitive expertise in moral philosophy is anything but settled.”

So Joachim Horvath and Alex Wiegmann (Ruhr University Bochum) decided to find out more on how such irrelevant factors influence moral philosophers’ intuitions about various cases through a large online study. The results were recently published in the Australasian Journal of Philosophy, some of which they share in the following guest post.*

Intuitive Expertise in Moral Judgments

by Joachim Horvath & Alex Wiegmann

Since experimental philosophy (or x-phi) got started in the early 2000s, non-experimental philosophers have thought hard about how to resist the challenge that its experimental findings pose for the method of cases. As it seems, people’s intuitive judgments about thought experiment cases are influenced by all kinds of irrelevant factors, such as cultural background, order of presentation, or even innate personality traits—to such an extent that some experimental philosophers have declared them unreliable and the method of hypothetical cases unfit for philosophical purposes.

The most popular response to the x-phi challenge has been the expertise defense, which starts from the assumption that professional philosophers are experts in their areas of specialization—in analogy to other disciplines, like law or math. However, x-phi studies until the early 2010s had almost exclusively been done with philosophical laypeople—and not with trained philosophical experts. So, according to the expertise defense, the inductive leap from laypeople to philosophical experts is unwarranted, and the burden of proof for showing that philosophers’ intuitive judgments are equally problematic rests solely on experimental philosophers here.

But it was clear from the start that the expertise defense might just be a way to buy non-experimental philosophers some time, maybe for thinking about a better defense. For, it is relatively easy to test the same irrelevant factors with philosophical experts that already caused trouble in laypeople. This is what happened in a pioneering study by Schwitzgebel & Cushman, who found that moral philosophers are equally influenced by order effects with well-known ethical cases, such as trolley scenarios or moral luck cases—even when controlling for reflection, self-reported expertise, or familiarity with the tested cases. These findings have been confirmed since then, and new ones, such as the influence of irrelevant options, have been added.

However, since only a handful of effects have been tested with moral philosophers so far, the issue of intuitive expertise in moral philosophy is anything but settled. We therefore decided to broaden the scope of the investigated effects in a large online study with laypeople and expert moral philosophers. The basic idea of the study was to test five well-known biases of judgment and decision-making, such as framing of the question-focus, prospect framing, mental accounting, or the decoy effect, with a special eye on their replicability (see our paper for details). We then adapted these five effects to moral scenarios, for example, to a trolley-style scenario called Focus with a question framed in terms of people saved or people killed. Here is the text of Focus as we presented it to our participants (with the positive save-framing in bold):

Carl is standing on the pier and observes a shark swimming toward five swimmers. There is only one possibility to avoid the death of the five swimmers: Carl could make loud noises, and thereby divert the shark into his direction. However, there is a fisherman swimming on the path between Carl and the shark. Diverting the shark would therefore save the five swimmers but kill the fisherman.

How much do you disagree or agree with the following claim:

Carl should make loud noises, which will result in [the five swimmers being saved / the fisherman being killed].

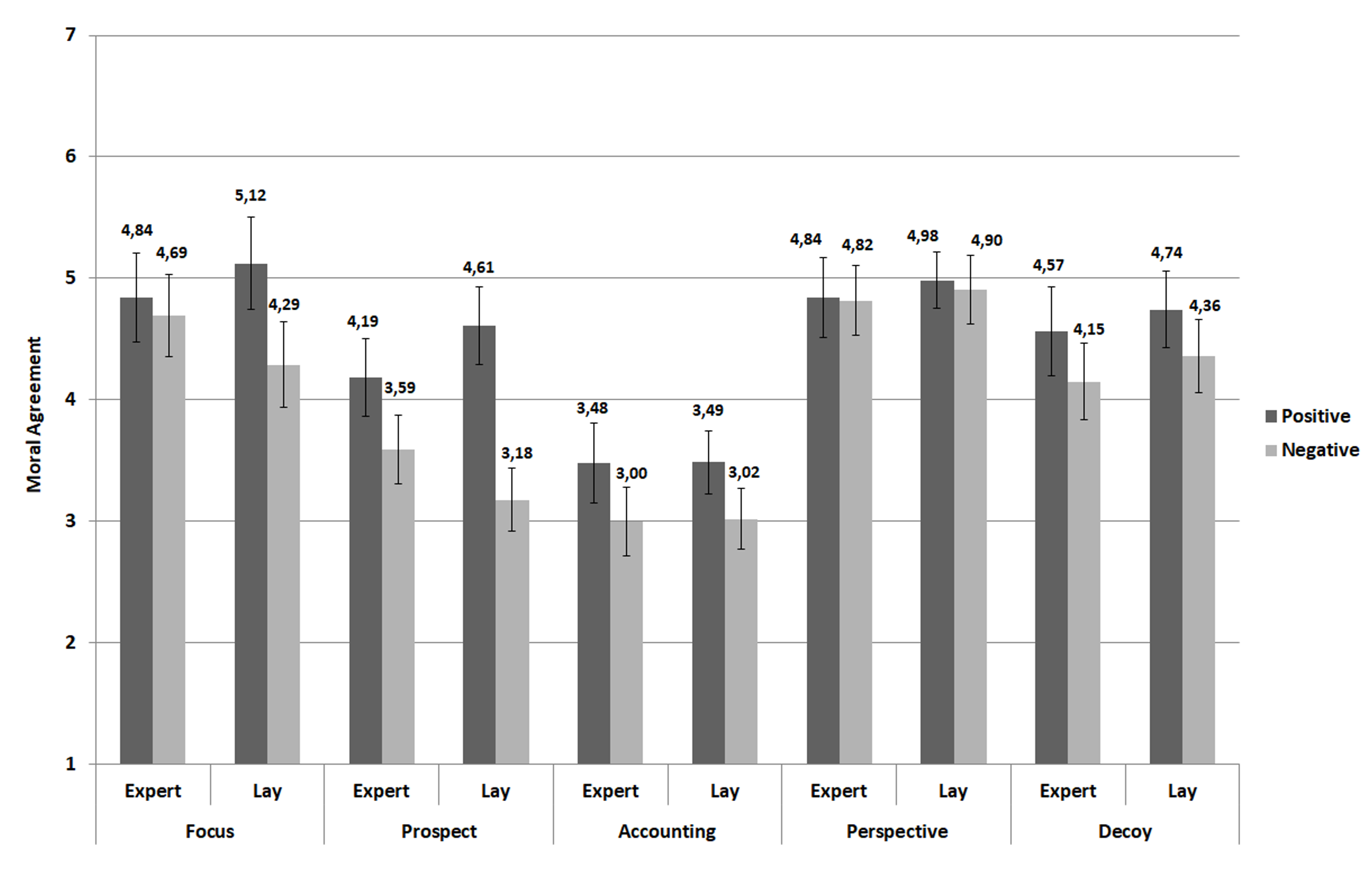

In our preregistered experiment, moral philosophers and laypeople were randomly assigned to one of two conditions of framing direction (Positive or Negative), and presented with five moral scenarios that implemented the five different framing effects (Focus, Prospect, Accounting, Perspective, and Decoy—always in this order). The framing of the scenarios was expected to either increase (in the Positive condition) or decrease (in the Negative condition) agreement-ratings for the presented moral claims. The main results are displayed in the following figure:

Across all scenarios, our manipulation had a significant effect on both moral philosophers and laypeople’s intuitive judgments. And while the size of the effect was descriptively larger for laypeople than for moral philosophers, this difference in effect-size was not statistically significant. Overall, the intuitive judgments of moral philosophers and laypeople were relatively close to each other—without any of the stark differences that one would expect in domains of genuine expertise, such as chess or math.

Concerning individual scenarios, we found the biggest framing effect for the most well-known scenario: Tversky and Kahneman’s prospect framing (aka “Asian disease” cases). Applying a strict criterion (p < .05, two-sided), Prospect was the only individual scenario with a significant effect in moral philosophers, while laypeople were also significantly influenced by the simple saving/killing framing in Focus. With a weaker criterion (p < .05, one-sided), laypeople’s intuitive judgments would come out as biased in four out of five scenarios (with the exception of Perspective), and those of moral philosophers in three scenarios (Prospect, Accounting, and Decoy). The outlier in terms of non-significance was Perspective, which tested an alleged finding of “actor-observer bias” in professional philosophers and laypeople. Our high-powered study suggests, however, that this is probably a non-effect in both groups (in line with another failed replication reported here).

What are the take-home lessons of our study? First, as in previous studies, expert moral philosophers are not immune to problematic effects, such as prospect framing, which adds to the growing evidence that tends to undermine the expertise defense. Second, unlike in previous studies, moral philosophers do enjoy a genuine advantage in some of the cases, most notably in the simple saving/killing framing of Focus, which was only (highly) significant in laypeople. We think that this is still cold comfort for proponents of the expertise defense, because one cannot predict from one’s armchair in which cases moral philosophers are just as biased as laypeople, and where they enjoy a genuine advantage. At best, our findings suggest the possibility of an empirical and more piecemeal version of the expertise defense. With sufficient experimental data, one might eventually be in a position to claim that moral philosophers’ intuitive judgments are better than those of laypeople with respect to this or that irrelevant factor under circumstances XYZ. How satisfying this would be for the metaphilosophical ambitions behind the expertise defense—and whether this would still deserve to be called “expertise”—is another matter.

[art: Phlegm, “Mechanical Shark” mural]

Very interesting! At the level of different effect types did you correct for multiple comparisons? I’m wondering how statistically secure the lower effects are for experts vs lay for Focus and Prospect.

No, we did not but I guess one can provide reasons for and against (treating the effects as different biases/effects). Anyway, the effect for Prospect would stay significant (p=.006 originally), but adjusting the one for Focus would render it non-significant (originally p=0.18). So one might be sceptical about Focus. Personally, I would bet on a successful replication since the effect for lay people seems to be real (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0010027721001220) and my intuition tells me that pilosophers are not/less susceptible to this effect (but I also thought – before I learnt of your study – that they would not be affected by the Prospect manipulation)

Thanks! That helps. I wonder if our findings on Prospect are within sampling error or each other or whether there’s some difference in the stimuli, population, or pre-stimulus materials that explains the difference.

Regarding the shark case, I wonder if the difference in intuitions based on the case being framed as one of killing or saving has anything to do with intention. Same physical action in either case, but done with a intention to kill in one case and an intention to save in another. If that’s right, I think it’s a substantive question whether the intuition is simply a morally irrelevant “bias”.

However, there’s nothing in the case that suggests that Carl might have the intention to kill the fisherman. Rather, the most natural interpretation is that Carl would have the intention to divert the shark in order to save the five swimmers, if that’s what he decides to do (in fact, the case description doesn’t say what Carl actually does, or will do, in the situation). So, given that the saving/killing-framing only has a significant influence on laypeople in our study, one could argue that if lay people’s responses are really due to projecting intentions in the way you suggest (which doesn’t seem overly charitable to begin with), they are simply misinterpreting the case – and so the experts would still have an advantage here (even if “only” in their better understanding of the case).

Assuming both that the framing in terms of killing versus saving points to the intention of the agent and that intentions in this (and similar) scenarios to the moral status of the action, you are right. But I do think that intentions should matter here (or in similar cases). Even if the agent has the worst of intentions (he hates the one person for some horrible reason) it does not seem of importance for the question of whether he should do the proposed action. For instance, image that the agent asks another person what to do in this situation, it seems strange – at least to me – to say something along the lines of “Well, that depends on your intention!” (in scenarios with identical physical actions and consequences). Scanlon (Moral Dimension) and Kamm (Intricate Ethics) forcefully argue against the claim that intentions matter in this kind of scenarios (might be different for assigning blame/praise though)

My point doesn’t actually require that intention makes a moral difference, though. Suppose, as seems plausible, that actions done with the intention of saving are typically good, and actions done with the intention of killing are typically bad (maybe because such actions are typically savings/killings, respectively). Suppose that it’s wrong to divert the shark regardless of intention. The intuition that says it’s okay when the action is framed as a saving but not as a killing is faulty. But, it’s still tracking something morally relevant, since the intention to save or kill typically corresponds with good/bad actions. So it’s not simply a morally irrelevant bias.

Thanks for spelling out your point! I agree that it might or even probably tracks something morally relevant and is thus not generally a bias. Perhaps one could say that it might be a good heuristic but applied to certain cases it can result in “biased” answers (as is the case with many useful heuristics)?

Something along those lines, yes. In general, I think apparent “defeaters” for intuitions are worth philosophical investigation in their own right.

A genuine question: has there been any work conducted (by philosophers, psychologists, philosophy-psychologists, psychologist-philosophers) assessing the external validity of thought experiment intuition cases like those used here and, well, just about everywhere else.

My question may not be about external validity, I suppose, but instead about ecological validity. I sometimes confuse which is which in contexts like this. What I really mean to ask is something more like this:

Do we have any reason to think that people’s moral intuitions about short written dilemmas tells us anything about how they would actually act in similar real-life situations?

If the answer is yes, I would really like to see some work that investigates these questions as I’m currently not aware of many (I’m familiar with some pseudo-versions of the trolley problem involving lab mice but I think those are far enough away from the trolley problem itself to not be useful).

If the answer is no, then I wonder why we (we philosophers, we psychologists, etc.) continue to use these sorts of cases when we study moral judgment. Are we really studying moral judgments when we do this or are moral judgments better though of as being tied to actual behavior? Do I count as a track switcher, for example, if I say that I would switch the tracks on the vignette version of the trolley problem but if I wouldn’t switch the tracks if I actually found myself in a trolley problem case?

This might be a crucially relevant question when we’re talking, for example, about moral expertise. Are debates about hypothetical moral expertise actually finding the relevant moral experts if they focus only on performance of PhDs on vignette cases? I’m inclined to say no in that I think moral expertise is action-oriented not knowledge-oriented but that takes us a little farther afield than my original question. Is there work on the question I asked? I’m genuinely interested.

I agree that there are problems with taking what people say about hypothetical scenarios as fairly straightforward evidence of their actual moral beliefs. But there are also problems with taking actual behavior as straightforward evidence of moral beliefs. Unless you think that people never act differently from what their moral commitments would suggest, actual behavior can be pretty poor evidence of moral beliefs too. That’s (one reason) why it’s important to ask people what they think morality tells them about various choices, and not simply what they would do in the situations. I can certainly think of many situations in which I almost certainly wouldn’t do what morality recommends, and anyone who says otherwise about themselves is lying or deluded.

If I am not mistaken, Joshua Greene writes something about this question in Moral tribes (moral judgments in hypothetical scenarios versus real life) and reports a high correlation. Kathryn Francis research (e.g. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0164374) employs virtual reality to gap the bridge (and surprisingly finds that people are more willing to sacrifice a person’s life). And here is a (quite unscientific) “field study” with people who were tricked into believing that they really have to decide decide whether to pull the switch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1sl5KJ69qiA (at about minute 16).

I don’t see how an expertise in having moral intuitions could be developed. I don’t think that intuitions serve as evidence of moral truth. I think thought experiments calling on intuitions are useful, but because they reveal our commitments to us, helping us to be consistent.

You are right that some kind of cognitivism about moral judgments is part of the dialectical context of our study. So, if you think that notions like reliability or epistemic trustworthiness don’t apply to moral judgments at all, this kind of work may not be so relevant or interesting for you. However, note that biases are still a problem if you think that intuitions primarily reveal our moral commitments, because these biases would then frequently prevent us from accessing our actual commitments. Here, I’m only making the very modest assumption that we do not have infallible access to our own commitments, and so can be mistaken about them sometimes.

You can think that moral judgments can be reliable and truth-apt, but still think that intuitions about cases aren’t reliable indicators of moral truth.

This type of science applied to philosophy always befuddles and amuses me! But, apart from that, what makes the so-called lifeboat, trolley, or (your version) shark scenarios moral or ethical problems? I think, at best, such setups are marginally in the realm of ethics. They remind me of Bertrand Russell’s no-win logical paradoxes—on the margins of logic or mathematics. Could it be like Captain Kirk that some folks just can’t stand no-win scenarios?