Results of the Philosophy of Science Association’s Climate Change Survey (guest post)

“There is a clear signal in these results that very many professional philosophers of science want to be working in a more online environment as a consequence of the climate crisis.”

That’s one of several findings of a recent survey conducted by the Climate Task Force of the Philosophy of Science Association, discussed in the following guest post* by Kerry McKenzie, associate professor of philosophy at the University of California, San Diego.

[Cheyney Thompson, untitled]

Results of the Philosophy of Science Association’s Climate Change Survey

by Kerry McKenzie

During March 2021, the Philosophy of Science Association Climate Task Force (PSA CTF) issued a survey aimed at gathering information on members’ experiences of working in a more online environment as a result of the Coronavirus crisis and gauging attitudes towards continuing with some of these practices in the service of the climate crisis. Below are described (1) the motivations for this survey, (2) its implementation, (3) the most significant quantitative results, (4) some of their implications, and (5) some of the lessons learned in the administration of this survey that we hope will inform future efforts.

1. Motivations

Motivating the formation of the PSA CTF was the conviction that philosophers of science, and hence the PSA, must play a part in the global movement to slash global greenhouse gas emissions by approximately 50% by 2030 and to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, as urged by the IPCC. Its aims are to (a) help the PSA reduce the Association’s associated carbon emissions and (b) assist PSA members in their individual efforts as philosophers of science to achieve this goal.

Since aviation-incurred emissions are a very significant part of the carbon footprint of contemporary academic research, an urgent question is how philosophers of science as a community can reduce the amount of long-distance travel they undertake as part of their professional lives. Unlike questions of, say, how our campus offices are powered, this is a question that we as a community can have a direct impact upon via the choices we make as to what meetings we attend and how we organize those meetings. Since these choices will in turn be a function of what other philosophers are doing and willing to do in future, the question represents a collective action problem—hence a problem whose solution requires common knowledge of the views of the community. Hence, our decision to conduct the survey.

2. Implementation

The survey was made available through a portal on the PSA website and publicized through an email to everyone on the PSA mailing list; an active membership was then required to gain access to the survey. This ensured respondents were PSA members but arguably created other problems, as we describe in Section 5 below. Current membership of the PSA is around 700 and in the end almost 200 members (189) took the survey. The full results will soon be available to members via the PSA website and will inform a discussion during the President’s Plenary at the 2021 PSA meeting in Baltimore. The most significant results of the survey however are outlined below.

3. Results

After being asked to detail their experiences of engaging in research activities in a more online environment over the course of the pandemic, respondents were asked the following question:

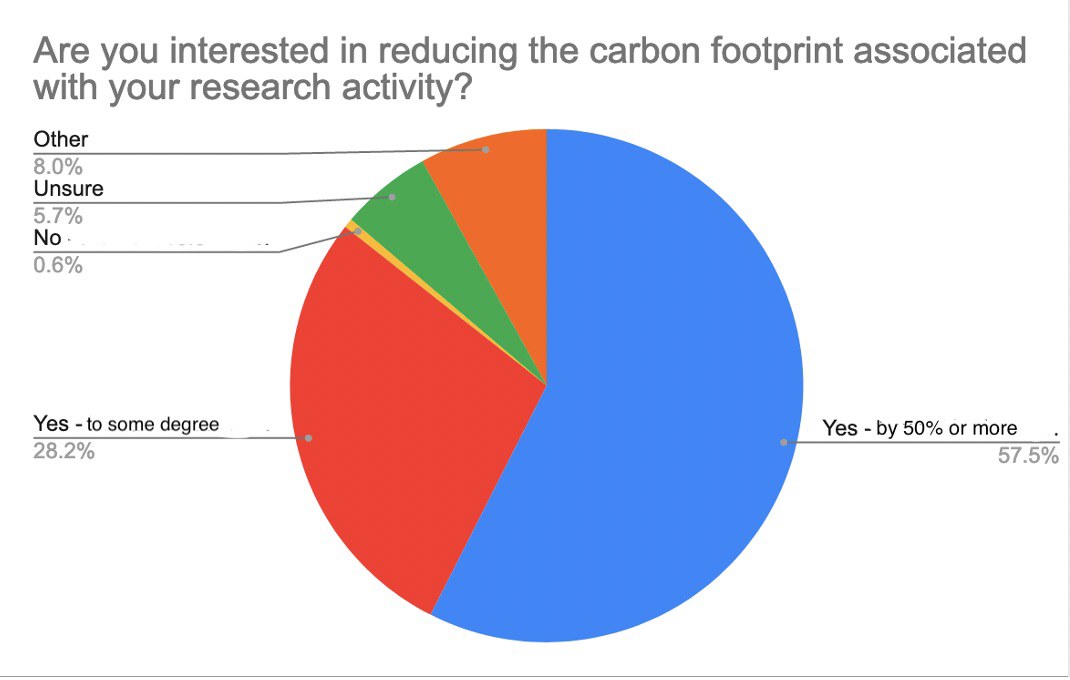

The United Nations International Panel on Climate Change states that a roughly 50% cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, relative to pre-2020 levels, is necessary to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. Given this, are you interested in reducing the carbon footprint associated with your research activity in particular?

The options given were:

- Yes — I would be interested in reducing it by 50% or more

- Yes — I would be interested in reducing it to some degree

- No — I would prefer my research activity to remain unaffected

- Unsure

- Other (please explain)

Over half of respondents (100) said that they wished to reduce it by 50% or more. 85% (49 respondents) said they wished to at least reduce it by some degree. Only one respondent said they wanted it to remain unaffected. 10 were unsure, and 14 had another response to the question.

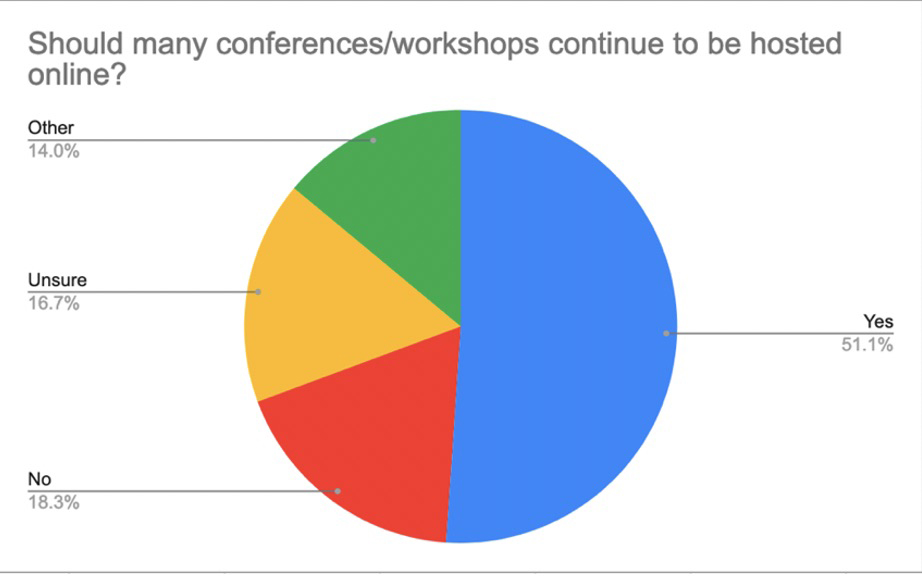

Respondents were then asked the question: ‘Given IPCC goals, do you think that many conferences and workshops should be hosted online?’ The options given were ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Unsure’, and ‘Other’ (please explain).

Results:

About half of respondents said ‘yes’. The remaining 50% was about evenly split between ‘no’, ‘unsure’, or had another response to the question.

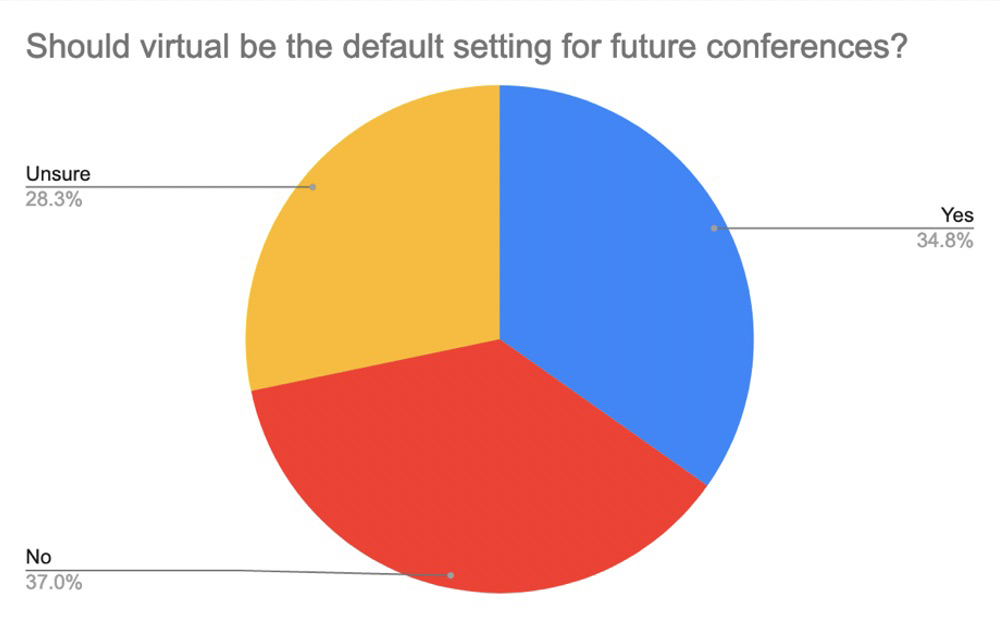

Respondents were then asked ‘Do you think that conference organizers should regard virtual as the “default” for meetings involving participants from distant geographic regions, moving to in-person only when they have good reason?’

There was a pretty even split between ‘Yes’, ‘No’, and ‘Unsure’.

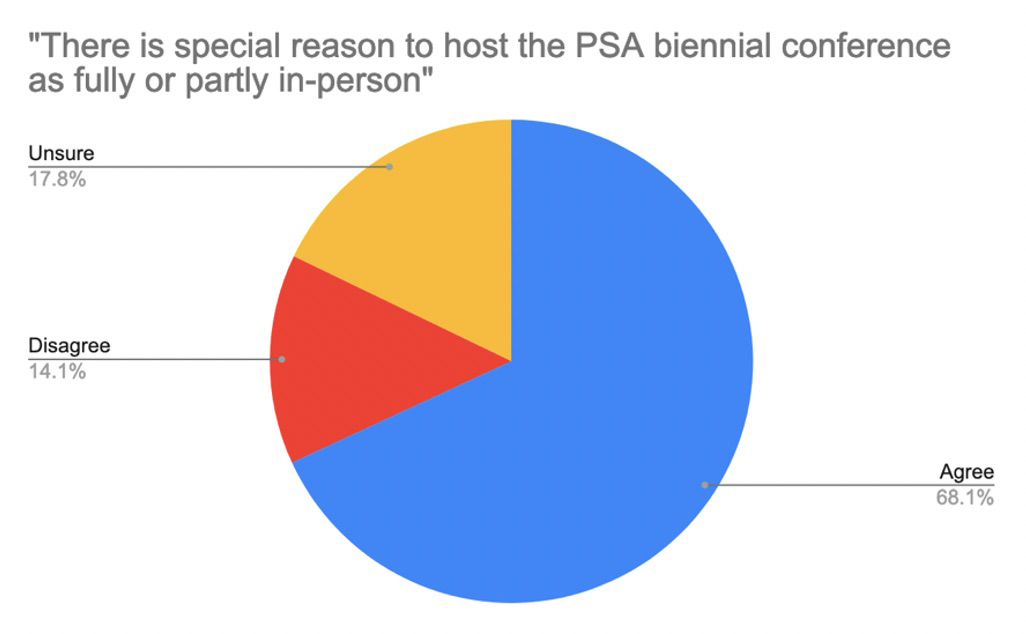

Respondents were then asked to ‘Please consider the following statement: “Even if we assume that more workshops and conferences should take place remotely, there is special reason to host the PSA biennial conference as fully or partly in-person.” The options given for a response to this statement were ‘Agree’, ‘Disagree’, or ‘Unsure’.

About two-thirds of respondents answered that there was special reason to continue to host the PSA meeting in person.

These we take to be the most significant quantitative results of the survey and the most useful for the community’s planning purposes. However, respondents were also invited to elaborate on their experiences of doing more workshops and conferences online. We will not enumerate these qualitative responses here—again, the comments in their entirety will soon be available to members via the PSA website—but suffice to say that in addition to some supportive comments it was clear that many respondents judged online conferences to be, in general, a pale imitation of in-person events. Some also enumerated ways in which they did not always better serve those with accessibility constraints. Others objected that focusing on academic travel was diverting attention away from other areas where we might more purposefully direct efforts against climate change.

4. Interpretation

It is not the purpose of this report to explain or evaluate in any detail the reasons behind why one might or might not wish to move to a more online meeting model, partly as there has already been so much discussion on this forum of the pros and cons of online working from the point of view of environmental sustainability, access and inclusivity, and quality (see e.g. Daily Nous post here and Daily Nous post here). Those discussions have already made clear that there are dilemmas posed along almost every relevant dimension by both virtual and by in-person meetings; that no one model will work for everyone, at every career stage, and in every locale; that reasonable people disagree about the issue of the effectiveness of these sorts of interventions; and in sum, that there is a plurality of views on virtually every aspect of these issues that deserve to be respected.

However, given the high level of support shown by the results of this survey for making a very significant cut in our research-related carbon footprint and for assuming that online is the ‘default’ for conferences moving forward (other than the PSA biannual meeting), we think there is a clear signal in these results that very many professional philosophers of science want to be working in a more online environment as a consequence of the climate crisis. This should be of interest to conference organizers regardless of where they themselves sit on the issue. We should after all presume that the views expressed by the majority of respondents are not unreasonable, and as such that people who hold these views should not be deprived of the goods associated with interacting with participants from geographically distant regions.

It is worth pointing out that the conflict that many philosophers of science seem to be experiencing between current professional norms and the challenge posed by the climate crisis evokes a scenario of ‘conscientious objection’ of the sort frequently discussed by bioethicists. In such scenarios, people experience a tension between their moral views and the expectations placed upon them as professionals—a tension which can result in them experiencing ‘moral injury’ as a consequence of doing their job. As is well known, many (though not all) bioethicists would argue that where the moral views concerned are not unreasonable, the correct response by their community is to minimize the professional harms suffered by those who refuse to engage in the practices that they regard as morally unacceptable—in part because moral injury should not be made a condition of doing one’s job. To be clear, the PSA CTF did not explicitly ask respondents whether they experience participating in a carbon-intensive research paradigm as a form of moral injury, or probe other relevant questions concerning morality that would be necessary to flesh out this claim. But regardless of the ultimate aptness of this analogy with conscientious objection, given the extent and the reasonableness of the desire of many in our community to reduce their research-associated carbon footprint, it behooves us as a community to determine the professional harms that may be associated with foregoing long-distance in-person meetings, and how these harms may be mitigated.

Finally, we note that there was a clear signal sent to the PSA that most members wish this conference to continue to take place in-person. This raises the question of how the PSA can reduce its own carbon footprint, and what the relative benefits of small- versus large-scale conferences are.

5. Lessons for other organizations and for future surveys

As already noted, there were problems with the implementation of this survey. In particular, by tying participation to an active membership we effectively imposed a ‘paywall’—to quote a word used by a graduate student who could not easily get access—that likely biased our results (although in which direction is unclear). In retrospect the timing was particularly unfortunate, as the fact that the 2020 conference was cancelled meant that there were fewer active memberships than usual. However, it did mean that we could at least be sure that it was PSA members that were taking the survey. Those who may be planning to undertake such a survey within a larger or different community of philosophers need to consider carefully how to maximize participation while still targeting the right demographic.

It is also worth reminding anyone planning more comprehensive surveys that—as anyone with experience here will know—getting the wording of questions right can be challenging (not least when the target audience is analytic philosophers!). Consider again the question reported on above: “The United Nations International Panel on Climate Change states that a roughly 50% cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, relative to pre-2020 levels, is necessary to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. Given this, are you interested in reducing the carbon footprint associated with your research activity in particular?’’ At least one respondent thought that this question was ‘egregiously leading’. But we had worded this question carefully, deciding in the end that (i) the qualification that it was research activity in particular that was in question mitigated its ‘leading’ nature (given that one could reasonably be disposed to reduce one’s carbon budget but see research as sacrosanct), and (ii) breaking the question down into simpler questions produced something unwieldy and (frankly) patronizing, given our target audience. Clearly not everyone agrees that we made the right call here—the lesson being that those planning to issue future surveys will likely have to make difficult choices regarding wording.

Finally, in retrospect we are unsure that we asked the most ‘actionable’ questions in this survey. Both the PSA CTF and our partner association Philosophers for Sustainability therefore invite input on what sorts of information other philosophers would regard as most useful from a planning perspective. Anyone with views on this issue can reach out to the Chair of the PSA CTF, Kerry McKenzie, or Philosophers for Sustainability via their website. Readers may also be interested to note that Philosophers for Sustainability are shortly (June 10th – 12th) running a Zoom conference on philosophy and the climate crisis, one focus of which will be a critique of extant research norms and strategies for changing them.

It’s really sad that because we spent a year and a half _managing ok_ in a zoom environment that some people now think we should just live like that all the time. If anything, this past year should have made it clear that the virtual model is a very poor substitute for real human interaction.

Aeon, unless you were at conferences every waking hour previously we are not suggesting you should live your life on Zoom “all the time”…

What I meant was, just because we made a temporary accommodation for the pandemic doesn’t mean we should keep doing it forever.

I think you are missing the climate crisis angle of this intervention. In any case, it seems many PSA members disagree with you.

Yes, that’s why I commented, to express disagreement. People will do what they’re going to do, I understand that.

come on, man

I don’t think anyone should interpret “cut emissions by 50% or more” as being synonymous with “cut 100% of emissions”.

These are interesting results. Personally, I have no interest in online conferences. I have attended them this past years, and not into it anymore. They do very little, if anything for me (for many reasons – from simply not really concentrating on the talks and losing overall motivation after a while, to finding it virtually useless in terms of scholarly improvement, etc.). At least in some areas, the conferences and meetings are not simply ways of exchanging information or receiving feedback on one’s work (i.e., conferences are not business meetings). Although this is certainly part of it, it is also about human and scholarly interaction outside the actual talks – perhaps even more so than about the talks themselves. It’s about being part of something and finding purpose and validation. It’s about friendships and passions. In some way, online conference is (to me) just a waste of time. I could just read a paper on my own. I expect, consequently, to simply go to less conferences in the future (instead of 3-4, maybe 1-2 a year, if I am lucky).

I agree with a lot of this, Joe, but the most important question here isn’t about which format is most useful professionally (though there’s a lot to be said about more innovative online conference formats, through which I’ve found friends and validation).

The most important question seems to be what event organizers should do in light of preferences like these.

A possible analogy: imagine a conference organizer for some organization was considering having an BBQ pork banquet. If a significant portion of the organization’s members (reasonably) found eating pork objectionable (for ethical or religious reasons), that would seem to give the organizer pretty strong reason to reconsider – even if another significant portion of attendees loved pork BBQ, and found talking while eating pork to be the best context for making friendships and talking philosophy.

I understand the question posed. I guess, in your example, I am one who would say that a vegetable loaf banquet is making me sad and disinclined to attend (although I am not sure this is a good analogy). I have nothing against people organizing these conferences, I just have no desire to attend them, esp. if like APA, they will make me pay money to do that (unless, of course, we end up in pandemic or otherwise extreme situations which make it impossible). I am less opposed to departmental talks being partially held this way (though only exceptionally), or to people coming to graduate seminars in this format, and so on. I can deal with a couple of hours for a one-time event of this sort. Conferences are a different matter for me. I also do not mean to underplay the environmental impact of plane travel (though I suspect academy is not the most important sector here). I am just saying online conferences are not (to me) attractive as a long term substitute and I’d rather do less or more local things (or do them in a more leisurly, say train powered, way).

Fair enough, Joe. I think the “doing less or more local” things is also a reasonable response to the climate crisis – especially for people in less remote areas.

And you’re surely right that the academy is nowhere near the most important sector when it comes to climate emissions. But our big conferences involve a lot of flights, and unlike, say, the entrenched political power of the fossil fuel industry, that’s something we can change right away (while working on other fronts).

Thanks for this really interesting pilot survey. I hope other, larger surveys happen soon and learn from this one.

It seems worth adding that conference formats are very rarely at or near their best in their first year. So the question is not whether our first rickety attempts were as good as in-person conferences, but whether continuing to explore and improve online conferences is the right response to a global emergency that is worsened by in-person conferences. Whenever someone says “never again” about virtual conferences, I want to ask them: why weren’t you also against going virtual during the pandemic?

One point of disagreement with the interpretation of the survey results: Believing in special reason is not the same as having an overall preference. I had special reason to visit my best friend this winter, but because of the pandemic I thought it better not to go. There is clearly special reason to hold a flagship conference in person, given its importance, and clearly special reason not to, given the climate crisis. So I’m not sure the question about “special reason” elicited respondents’ actual preferences about whether to hold the PSA biennial meeting in person. I would be interested in seeing survey questions that ask directly about preferences or overall evaluations, and also ask about alternating between in-person and virtual conferences, which might be an appealing and attainable compromise option.

Agreed that we could / should have worded that question differently and relied less on context!

I think the person who claimed the question was “egregiously leading” failed to distinguish between the epistemology of climate change and the ethics of climate change. The person may had bad faith if they felt compelled to answer it in a particular way that they were not forced to.

It may come to as a surprise for many or most people, but there are those who accept the evidence of climate change, but also don’t care about it.

Therefore, that question was actually epistemically fruitful and if it were targeted towards the general public, we’d have some insights into how much of a tension between knowing about climate change and people’s care about it within the general public.

A third option is holding the conference in-person, but requiring attendees to offset the emissions from their travel. For those interested, I defend such offsetting in this (working) paper.

While I don’t think your ethical reasoning is prima facie wrong, calling this an option with no readily available means of doing so seems a bit misleading. At least, it does not seem to address the current live issue.

One option: https://www.climeworks.com/

It might work better to build the offsets into the conference budget. (Probably depends on the conference and its funding model.)

I just have questions, maybe leading questions given I have some skepticism here, but they are based on the fact that I have little confidence in my own ability to assess them. So here goes:

I want to emphasize I’m not trolling or being disingenuous. But I think we collectively need some real statistical ground for understanding the effectiveness of our actions to limit climate change, even if, as I think they are, morally principled.

These are the right questions. I sometimes wonder whether we’d be more effective not by cancelling in-person meetings but by persuading our students not to buy F350 Extended Cab Super Stroke V8 Mega Stomper trucks, which are not necessary for bringing the new Peloton home from the mall.

If you aren’t already familiar with it, check out Kagan’s “Do I Make A Difference?” for a response to your (1).

And check out work by Julia Nefsky or Mark Budolfson, among others, for powerful responses to Kagan’s argument.

Alan, I myself don’t think of it in terms of “what difference can philosophers make?”, even if the answer there is: a basically negligible difference. The reasons is that you could say the same thing about virtually every academic field, every academic institution, almost every private company, and so on and on until you get all the way up to largish nations and fossil fuel execs. The question I ask myself is what should do *we* do, given that nobody can do everything and everybody can do something? I note also that many other academic disciplines are engaged in a similar conversation: see eg

the Society for Cultural Anthopology (https://culanth.org/fieldsights/reimagining-the-annual-meeting-for-an-era-of-radical-climate-change?fbclid=IwAR0Ghv8gWx-Gb-sw1fTJbgIVhXYQf2Zxt1AhU4OuO9iyGr7jtUeLWj9lw3w) ,

the American Association of Geographers (http://news.aag.org/2019/10/introducing-the-climate-action-task-force/),

the Society for Classical Studies (https://classicalstudies.org/about/scs-newsletter-may-2021-climate-and-organizations),

and I could keep adding others. So it’s not like it is just philosophers thinking about this. In fact we are, as is often the case, arguably behind the curve.

“The reasons is that you could say the same thing about virtually every academic field, every academic institution, almost every private company, and so on and on until you get all the way up to largish nations and fossil fuel execs.”

Correct, which is why we should be exerting pressure on fossil fuel companies and governments (sub-national governments included). Shareholder actions have been bringing out some positive change lately, for example.

If it became financially prohibitive to hold in-person conferences due to government climate policy (e.g., major tax increases on fossil fuels) that had a positive effect on global warming, I would gladly accept the move to online. But why should we sacrifice something of real value if doing so makes no difference to solving the problem that motivates the sacrifice in the first place? The moral obligation is to do something effective, not just to do something.

A couple thoughts on this: First, reducing the number (nobody here is proposing eliminating) in person conferences is a sacrifice for some people. But it benefits many others, who cannot travel for various reasons.

Second, our profession is small, but a big shift with us will have ripple effects. We don’t know how large those effects might be, but a lot of people in politics (often via law) come from philosophy, so there’s some reason to think that they could be significant.

A minor comment (I’ve said most of what I wanted to say on the broader issues on the other DN threads): I don’t think thinking in terms of personal sacrifice is quite right. The case for in-person conferences, insofar as there is a case, is that curtailing them will harm research in our field (in short-term ways as research-advancing discussions go less well, in long-term ways as networking atrophies).

David, I know you’ve already pitched in a lot on this issue and we’ve talked a lot already. But just to reiterate that I take issue with your assertion that even ‘curtailing’ in-person conferences will result in ‘networking atrophy’ as if that were just a straightforward fact. It is not! By moving to a more mixed model — such as the one a majority of PSA members seem to wish to see, in which there is still the big PSA meeting but lots of smaller more focused online events — we can get the best of both worlds. And it is likely an awareness of this possibility that has in part caused people to vote as they have (as one can assume that active PSA members value the quality of phil sci research and appreciate how our networks of interaction promote it).

I for one have really expanded my own network of collaborators through this last year — while continuing to cherish relationships that I’ve been able to build in in-person settings (such as with your good self!)

Kerry, as a preface, I have enormous respect, not just for you, but for your work in philosophy, which is a personal inspiration to me. I want to report, however, that for some of us the last year has caused our network of collaborators to wither (b/c we have trouble communicating w/ others online, and only feel comfortable talking philosophy in person). Perhaps this is simply our problem. (I truly am open to that possibility.) And perhaps also the benefit to the overall effort to fight climate change is worth it. But it is worth pointing out.

It’s not just you, and it’s not just your problem. This is why people come together in groups to confer. Video chat is slightly better than a conference call, but still vastly inadequate relative to coming together to meet in person, Don’t feel guilty for feeling that way.

Aeon Skoble — in many ways, yes. Hence a motivation to really try and develop local networks wherever possible that will provide the best of both worlds.

First of all, thank you for your nice words. I absolutely agree that the interests of early-career folk have to be front and centre in these deliberations. And please be absolutely clear that all that anyone is calling for here is more of a mix-and-match than before. I’ve been speaking the last year with people with all sorts of preferences for all sorts of reasons: people who prefer online for accessibility reasons, and people who prefer in person for a different accessibility reason; people who feel much more comfortable on Zoom discussion because that way they don’t see/ feel people starting at their body the whole, and also people who feel Zoom really alienating… We’re a diverse bunch!

One thing that I see all the time though and that I want to mention in connection with grads specifically is major-league philosophers defending their major-league fossil fuel consumption habits by reference to the opportunities that their presence at conferences provides to grad students. And while I think a lot of that is overstated (not to mention a little, let’s say, convenient), I also completely concede that early connections can be utterly crucial. But here at UCSD our grad students have been engaged in really focused reading groups which include the author of the paper we read that week. It seems to me that that is a really meaningful forum for interacting with top-of-the-shop scholars and showing what they can do — and much more systematic and less financially discriminatory than an impromptu meeting in a clammy hotel bar!

I completely agree that something like getting the author to appear at a reading group is a terrific use of Zoom and an example that it can increase research quality. (I have some worries about how well this will work in hybrid mode but they can probably be overcome.)

But of course that’s not replacing existing in-person events. (You almost never get a reading group that flies all its authors in.) It’s a (really nice) addition to in-person interactions, not a substitution.

Kerry: dialectically speaking, I’m not asserting it. What I said was that insofar as there is a case for in-person conferences, the case rests on the harm caused to research (including research networks) by curtailing them. That’s entirely compatible with thinking that curtailing them won’t actually cause harm, from which it would follow that there isn’t a case for in-person conferences.

As it happens, and as you know, I do think there are serious research harms that will follow from substantial reductions in in-person meetings. But when I have said that (e.g. in the other DN threads) I haven’t just asserted it ‘as if that were just a straightforward fact‘: I have argued for it, extensively. You’re not obliged to accept those arguments, of course! But it’s not fair to say that I’m not making them.

Separately: is it really established that ‘a majority of PSA members seem to wish to see’ a hybrid model? It looks pretty much evenly split to me: 51.1% of people want to see many workshops continue to be held online. (51.1% is >50%, I suppose, but not to a statistically significant degree – and it would have been 50.8% had difficulties with the website not prevented me from voting!) I’d be willing to concede that ‘a plurality’ of members want to see it – there are many more ‘yes’ than ‘no’ (and I’m ‘unsure’ myself, more because I see some academic advantages in a hybrid model than on climate-change reasons).

I was looking for a comment like this and it’s disheartening to me that I had to scroll so far…

Did we all along think our work was of such trivial importance that improvements in research quality and output are unlikely to justify emissions, but having more fun at a conference might well justify them?

To be fair to Kerry, she (as I understand her) believes both in the importance of our research and in the genuine contributions that in-person meetings make. The questions are (a) whether there’s a strong climate-change imperative to reduce those meetings even so, and (b) whether I and others are too pessimistic about how we could reduce in-person meetings without big negative research consequences.

(I realize belatedly that the DN system is flattening comment threads below the 5th iteration. My first post is a reply to Kerry McKenzie’s post at c.11pm Eastern. My second is a reply to Kerry’s post at c.3pm Eastern. My third is a reply to TN’s post at c.7am Eastern.)

Moti, it probably won’t come as a surprise to hear that myself and others on the PSA climate task force / Philosophers for Sustainability are also actively engaged in projects such as decarbonizing our campus; organizing fossil-free commutes; divesting multi-billion dollar university pension funds of all fossil fuel investments (both explicit and implicit); working to change university ethics codes to include disclosure of fossil fuel funding along the lines of funding from big tobacco, and so on and on.

So it’s not like the question here is: “Why this action and not that?”. Because unfortunately the answer to the question of which climate change action is always: ‘All of the above’.

I think there is much more to be done in this direction but I think local initiatives are, frankly, not particularly important. The problem is our whole way of life, not whether or not a university has investment in fossil fuels. When I came to USA about 25 years ago, I was shocked – completely shocked – by the amount of food wasted in front of my eyes everywhere, the amount of waste produced by regular daily activities, the amount of energy wasted just to make things more comfy (from the ubiquitous laundry dryers, to-go cups and silver ware, to air-conditioning everywhere, to the habit of showering constantly – in my country the people working on tourist ships can tell nationalities of the guests by the amount of water they use daily – Americans spend several times more than other people, and so on). It’s the way things work – when I go home, I notice I produce maybe 1/4 of waste than I do here and I am rather conscious of it. If you could just stop wasting food, you could probably reduce agriculture by 25 percent. And although USA is a particularly egregious case, the same goes for other places – we cannot have restaurants, bars, coffeeshops, concerts, movies, tourism, cell phones, cars, and so on – without causing serious harms. I picked on US because it was the first time I realize – by way of contrast – how wasteful modern, capitalist societies are. All this requires long-term and strict governmental action, laws and the whole country/countries changing habits. Frankly, I don’t see it happening unless this a matter of serious, visible and palpable threat. And maybe not even then.

Overthrowing capitalism is probably not in the PSA’s remit.

Sure, but so is not preventing global climate change? In any case, my point was (not particularly well-expressed, really) that the various proposed modifications of academic life are more about (some) people feeling good about themselves than about actually making difference and that, pessimistically, I am not sure what could make a difference as the problem is the whole way of life that we value and want. I do not think we (people) are going to stop flying – families and friends and businesses have become global, and the desire to see the world and now having the means to do so in a large chunk of population is too entrenched. And even if we reduce flying, there will be other things creeping in – from bitcoin to increased consumption of beef (somehow the many philosophers who lead by example of veganism are not making a dent) and even more mining and very energy-consuming and envir. polluting production of more and more life permeating electronics. It’s like people who prefer alluminium cans to plastic bottles to reduce plastic waste while having no clue about what pollution and energy alluminium production causes.

Kerry, appreciate your efforts, and your point that this isn’t an “either/or” situation with exclusive disjuncts. I’m just not convinced about the value of moving online for climate reasons. I certainly don’t mean to discourage anyone from doing what they can to contribute to the mitigation of the crisis.

And, also, I think in-person conferences are valuable along more than one dimension, and so I’m not thrilled about the prospect of them going away. Especially when there are so many other domains in which the greenhouse gas contributions are worse and the value so much less.

In terms of CO2 emissions associated with our own activities it’s very hard to beat not getting on a plane.

https://www.reddit.com/r/dataisbeautiful/comments/njw7kg/oc_comparing_emissions_sources_how_to_shrink_your/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=ios_app&utm_name=iossmf

Doesn’t this assume the flight wouldn’t happen if I weren’t on it?

But I doubt that anyone is thinking that if a single philosopher, or a handful of philosophers, take fewer planes this is going to have a direct and non-negligible positive impact on carbon emissions. Indeed, as Kerry McKenzie noted above, even if the philosophical community in toto were to commit to flying less this would make only a near-negligible difference, in and of itself, towards reducing carbon emissions. But I don’t take this to imply that it would make no difference whatsoever. Philosophers committing to fly less may not have a direct and/or immediate non-negligible impact in and of itself, but this doesn’t mean it couldn’t have an indirect and/or delayed positive effect (which would then still serve as practical/moral grounds for action; this is how I read Kerry McKenzie’s remark that “nobody can do everything and everybody can do something”).

For example, one way to think about the latter might be the following: “If philosophers collectively commit to reducing yearly air miles, and other academic communities do the same, also (not only, not primarily, but also) encouraged by the example set by (among others) philosophers, and this in turn plays even a small part in encouraging other categories to follow suit, then the overall knock-on effect will positively impact (lead to a reduction of) carbon emissions. By contrast and conversely, any community or category that stops short of making such a commitment will effectively set a small but cumulatively non-negligible ‘bad example’ – encouraging others to maintain the status quo.”

(I realise this is coarse, naïve and leaves lots of stuff out – apologies.)

There are about 1.5 million academic employees in the US. Around 3 million people travel by plane daily (pre-pandemic, that is). I don’t know how many academics would fly daily, but let’s say it’s 10 per institution on academic (conference) business (as opposed to personal or administration). This would be a number to know (I just estimated my university, which is a research one, so it’s probably less). There are 5000 or so, that’s 50.000 daily. That’s 0.16 (let’s say 0.2) of all daily travelers. In a 150 people plane, that’s 1/3 of a passenger.

I don’t deny such a thing is possible. But so many ifs, mights, and mays, and in the meantime we would–in my view quite certainly and obviously–be sacrificing something of value.

It’s also possible that if I spend my days doing nothing but writing strongly-worded letters to elected officials and corporate overlords that one of them may be convinced to take climate change more seriously, and this, in turn, could lead to non-negligible reductions in greenhouse gasses. But I’m not going to do that, either, because although the upside is significant, the odds of my actions leading to that upside are very unfavorable, to say the least. And that’s kinda what I think is going on with the move to avoid conference travel.

I can’t control what *we* do, except indirectly. If ethics is supposed to guide behavior by telling them to act, I don’t see why anyone should care what we should do (except indirectly, insofar as my choices affect the choices of others). (I grant that it at least makes sense to speak about group obligations.) I’m not saying that the effects of one’s actions determine their moral status; maybe I should act in a way that is universalisable for example. But there’s a large step from what we should do to what I should do which needs to be briefed before anyone should think the former provides reasons for the latter.

Ok let me reply to myself here to avoid saying anything to anyone who replied in this sub-thread specifically.

First, I’m gratified to have had so many different comments and thank all for weighing in.

Second, I wish I’d heard a bit more about how relatively small groups do/can affect real change on a truly global scale. Sure, if we contribute to say, magnifying generational change about climate-related actions, long-term positive results are possible. But one specific problem about climate change is that we are apparently in a relatively small window of time where we collectively can make a difference (if I understand the current science). We do not really have generational-scale time to act. So–the question then is what actions are most likely to have the greatest impact in the shortest scale of time? That I guess was the basis for my original questions above.

Third, what strikes me in our present US political situation is how fragile our own country’s overly large influence in these matters is given the radical divisions in this country. It appears to me–I’m just an informed political observer mind you and nothing close to an expert–that our individual and as-much-collective-as-possible actions should be to assure that our government from top down is committed to reversing dangerous climate-related policies. That means direct political action in support of reversing of such policies. Yes, our individual and group behaviors are important in reflecting that support, but it seems to me given four years of undoing responsible climate policy on a global and national scale that was barely opposed in the results of the last election (remember that 300k votes properly distributed could have resulted in the maintenance of harmful policy) should be of immediate and utmost concern. Not to mention that we in the US are barely hanging on to something akin to representative democracy to accomplish anything that smacks of progressivism. It seems to me these political issues dwarf those that focus on smaller-scale questions.

But again, I’m just one not-the-most-informed voice that is overall interested in effectiveness of action. That’s where I’m coming from, and that’s what I want to hear about.

I applaud the PSA for launching this survey and thank Kerry for this excellent write-up. Our carbon footprint is an important issue, and with the pandemic receding in some of the west, now is the opportune time to have discussions about what worked and didn’t when we went online.

Frankly, I find some of these comments very depressing. It’s like reading nextdoorneighbor, which one shouldn’t. All sorts of “academic” issues are arising — in the pejorative sense of the word. Will this solve the climate crisis? (No, duh.) Kerry doesn’t want us to ever fly again! (No, you’ve created a straw women via slippery slope, and I bet she wishes you’d visit your mom more often.) What’s the PSA’s take on Sinnott-Armstrong vs Broome? (PSA: Broome :)) How do we get from “we” ought to do something to “I” ought to do something? (Universal instantiation). If some of the commentators were in charge of the civil rights movement we’d still be living in the 1950’s.

Many faculty and universities want to be beacons of how to be more sustainable. We owe it to our students to be living laboratories of how to deal with the climate crisis. Societies and departments all over are busy discussing this question. Philosophy should too. Everyone agrees that dropping all in-person events would be a disaster for philosophy. But the survey shows that a good chunk think some activities that were in-person could go online. Where to go between these two poles is a serious practical question, one that I hope departments and societies will discuss. Hopefully we’ll run a natural experiment with a variety of models and develop a consensus about what works best.

“Everyone agrees that dropping all in-person events would be a disaster for philosophy. But the survey shows that a good chunk think some activities that were in-person could go online.” Right, because it’s easy to say that what _other people_ do is frivolous and can be duplicated virtually.

No one is saying that anything is frivolous or even that anything can be fully duplicated virtually. I think flying a single colloquium speaker 3000 miles for a two-hour event is now hard to justify doing too often. That doesn’t mean I think what the speaker does is frivolous or even as good as an in-person event. It just means that I think, all things considered, the benefits of a hybrid strategy outweigh the costs. For instance, it means we get to hear the speaker in the first place, since flying them out might have been too expensive.

Were there many people who’d fly 3000 miles just to give a talk and then go home? I’d assumed most people were like me in that situation: if you do it, come for several days, have a bunch of long conversations with various people and groups in the department, probably give another talk to a specialist subgroup or a nearby department or something.

Yes, although whether they go home or to the beach I don’t know—but in, out. But this is the sort of contextual info that makes too formal an approach to a hybrid model hard. For you, you’re known to love philosophical interaction, the more the better. And coming to UCSD we’d have grads and faculty who have read your work and would benefit from extended interaction, not just the colloquium. On my personal weighting, that would justify the 2437 miles (i checked) between the two (assuming we had money, and bearing in mind that flight costs and distance don’t covary very well); and on your end, maybe you’d work in a visit to UCI or LA too… Now, probably we implicitly took most of this into account often when issuing invitations beforehand anyway; still, I think we can take the carbon costs and pros and cons of the new technology as factors in this calculus too.

But as someone else noted upthread, the plane is flying from LGA to LAX whether that speaker is on it or not, so I’m not seeing the pollution benefit of not inviting him or her.

1. Well, of course, if the norms in enough groups changed then it *might* be that a plane doesn’t fly. This is to rehash all the Sinnott-Armstrong, Broome, and Kagan type work, and before that, Singer and others on small differences and thresholds. I’m definitely on the Broome side of things here.

2. But even if all the planes would still fly and no threshold was reached by this norm shift, I want to do my job in a socially responsible way. Our students are disgusted by earlier generations gobbling up all the resources and destroying the earth without concern. I think universities can be models of how to handle the climate crisis. How can we do that if we don’t at least take our carbon footprint as one factor in our decisions?

“Thinking about our carbon footprint” can’t mean “stop doing our jobs.” Teaching in-person classes, going to conferences, and hosting (and being) visiting speakers all consume resources but are all part of our job. Students who think it’s “disgusting” that their profs have arranged for a visiting speaker to come are probably not checking their privilege. If you’re at a super-elite institution maybe you don’t think you “need” to see a visiting speaker (though that too would be false) but maybe students at state schools appreciate the expansion of opportunity this represents. Similarly, maybe profs at super-elite institutions don’t “need” to go to conferences, but most of us do. The reality of academic travel is presented in these discussions as if we were taking private jets to Davos and Maui 3-4 times a year, when the reality is more like flying coach to Cleveland a couple times.

Point 1: It’s certainly true that if enough people stop flying, there will be less air traffic. But that’s not the question at all (if it ever was) – the question is if we reduce in-person conferences and talks, will that reduce flying or have enough positive effects on environment (including inspiring others) to outweigh potential losses of other kinds (social, research, and so on). This second question is much harder to answer. I am for example sure that cancelling APA conference entirely would be of benefit as that is a significant number of people. And I am pretty sure people at top departments won’t miss it.

Point 2: I didn’t think it was about an individual feeling good about themselves. I certainly I am glad to hear that. But at least my job influences other people – I am given opportunities and I give opportunities. I don’t need them anymore really but does that mean I can now decide to take them for others just so I can, on a certain conception feel socially responsible? I assume every young generation is disgusted with the older one. I was too. That seems to go neither here nor there. In any case, nobody here is arguing not to take carbon footprint seriously – just some of us think that cancelling or reducing in-person conferences is not in fact the thing to concentrate on since it makes virtually no difference (and probably won’t have any impact on anybody or anything either other than people not meeting).

Some of these questions are empirical questions. There are now systematic projects underway mapping the emissions associated with academic research that will decide some of these, for example this one: https://allea.org/new-project-to-explore-climate-sustainability-in-the-academic-system/?cn-reloaded=1

On 1, we’re not disagreeing. I’m just saying that our carbon contributions should be a factor in our decisions. the hard question is then what I want to turn to.

On 2, appealing to causal impotence is a way of saying that there are only costs to green policies and no benefits. But the casual impotence argument is terrible, and even if it weren’t, there are external benefits that accrue from acting as a socially responsible model for our students.

All I’m saying is that the carbon contribution should count as a factor in the cost-benefit analysis we as a field do. if a department has to buy a new refrigerator, should it go with the energy efficient one or the old inefficient horrible model? Well, if the efficient expensive one means no pizza at the student Philosophy Club and then no one shows up, well, that’s one strike against the green frig and something to take into account. But you seem to be suggesting to not bother with that calculation, just buy the old inefficient clunker because what difference does it make?

I am suggesting that as long as the cost of electricity is as low as it is in the US and, relatedly, the overall culture is one in which wasting energy is completely internalized (to the point that most people do not realize that they are doing it at all), it doesn’t matter what a philosophy department, full of entirely atypical people in terms of what they take into account when deciding things, buys. It doesn’t matter. Hence, what I am saying is that this is the wrong place to focus on if you do want to make a difference. It’s like any other academic squabble. It’s about scoring moral points, not really about doing anything. At the same time, I am very pessimistic – or maybe gloomy – about what there is one can do precisely because of all this. What do you do in a country where a significant percent of population doesn’t really care about environment and smaller, but serious percentage still (maybe 1/4?) doesn’t even believe in climate change? And all it takes is a few thousand votes to elect someone who will act accordingly? And those others won’t do much either (cosmetics only) as it is politically a non-starter? And, even if they did, how do you change a whole way of life, focus on consumerism, economic growth and so on? To take your example – the problem is not that I thin you shouldn’t calculate which fridge is more efficient – the problem is that you think it trivial that you need a fridge in the philosophy department – also a coffee machine, bunch of computers, copy machine, air – conditioning. projector, and so on. That the vast majority of employees and great many students commute by car (and if they need to buy a milk take a car to do so). And so on. From this point of view, buying more efficient fridge is…who cares?

Renewable energy increasingly seems to break the connection between electricity use and environmental harm, though, at least in the medium term. ‘Electrify everything’ is a fairly common slogan now in the more quantitative anti-climate-change literature.

The global fossil fuel consumption is still increasing, as far as I know, since the demand for energy is increasing too (and fast). It’s not that we use more renewable and less fossil. We use more of both.

I find it strange that people make this argument when it comes to flights and flights alone. When presented with an argument that you should eat fewer steaks on environmental grounds, no-one says “But the cow is going to be raised and killed anyway!” Obviously the market will respond to demand.

Well, people do say this. It’s the “causal impotence” objection to ethical vegetarianism motivated by utilitarianism, though that usually has to do with animal welfare rather than the environment. But it seems to me that the environmental argument for avoiding meat is even weaker than the animal welfare one. Mark Budolfson has done interesting work here. The crude summary is that the market is too large to be sensitive to the choices we make as individuals, so that even if I and everyone in my family and circle of friends stops eating beef today, we won’t save the life of a single cow. Of course, if millions and millions of people stop, then fewer cows will be killed. But I can’t influence millions and millions of people.

I don’t like this argument because I don’t like the conclusion, but I’m not convinced it’s a bad argument.

Yes, Kerry, the causal impotence argument is all over this thread, which is what I found so depressing. No solar on my house, no efficient water heater, buy the gas guzzler, don’t bother reducing meat, and so on, for what difference does anything make? I think it’s a terrible argument. What I find so depressing is that I bet other societies and fields are weighing the pros and cons of greener policies whereas here we’re instead distracted by this demoralizing philosophical argument.

I agree the argument is demoralizing, but I’m not sure it’s unsound. I’ve published a paper arguing against it but haven’t entirely convinced myself.

“No solar on my house, no efficient water heater, buy the gas guzzler, don’t bother reducing meat, and so on, for what difference does anything make?” Who has argued for this and where? That’s a ridiculous interpretation of what some of us were saying. It’s like me saying that you are arguing for going back to pre-industrial society. The argument was about disrupting or doing away with a significant part of academic profession, one that, for many, is one of the main draws and attractions of it (insofar as the human/social as well as research aspect of the job is concerned) and whether the reasons for doing so are sufficiently good, outweighing those other benefits. My view was that they are not and one of the reasons was the benefits are, in the context where they are operative, insignificant, while the losses, in the context where they belong, very serious. This might be different for other things (say, I do not lose anything by recycling or switching to more efficient lights). There was a related discussion about what does make actual difference for environment and climate change quite in general and that’s a separate issue.