Online Conferences: The New Default (guest post)

In the following guest post,* a group of scholars make the case that the online conferences, the recent prevalence of which has been spurred by pandemic precautions, should be “the new default.”

Online Conferences: The New Default

by Rose Trappes (Bielefeld), Daniel Cohnitz (Utrecht),

Viorel Pâslaru (Dayton), T.J. Perkins (Utah),

and Ali Teymoori (Helmut-Schmidt)

As vaccines roll out and the corona pandemic looks to have an end in sight, academics face a choice. Should we move back to in-person meetings, or should we continue online? The global shift to online conferences, reading groups, teaching and meetings forced by the pandemic has been welcomed by some, but there were a number of cancellations and concerned voices suggesting that video calls are no good alternative to in-person meetings.

In a paper just out in the European Journal of Analytic Philosophy, we argue that philosophers should embrace online conferences as the new default for reasons of sustainability, accessibility for minorities in philosophy, and lowering the financial burden of conference organisation and attendance. We present survey data from four online conferences: The European Congress for Analytic Philosophy, and the colloquia Doing Science in a Pluralistic Society, Eco-Evo Mechanisms, and Philosophy of Biology at the Mountains. Our data indicate that online conferences are satisfactory in terms of sharing knowledge and getting feedback and seem to be more accessible, falling down only in networking. In-person conferences, we conclude, should in the future be restricted to limited and well-justified departures from a new normal of online conferencing.

As well as arguing for more online conferencing, we provide some guidance for organising a good online conference. Some of this comes from our data. Our survey compared a large conference in which speakers pre-recorded their talks to several small conferences in which the talks were live. We found that both pre-recorded and live talks were seen as largely satisfactory by both presenters and audience members. We also found that participants prefer to have networking in small groups (using functions like breakout rooms in Zoom), such as coffee breaks, happy hours or group work. Based on our experience, we outline two models for online conferences with pre-recorded or live talks.

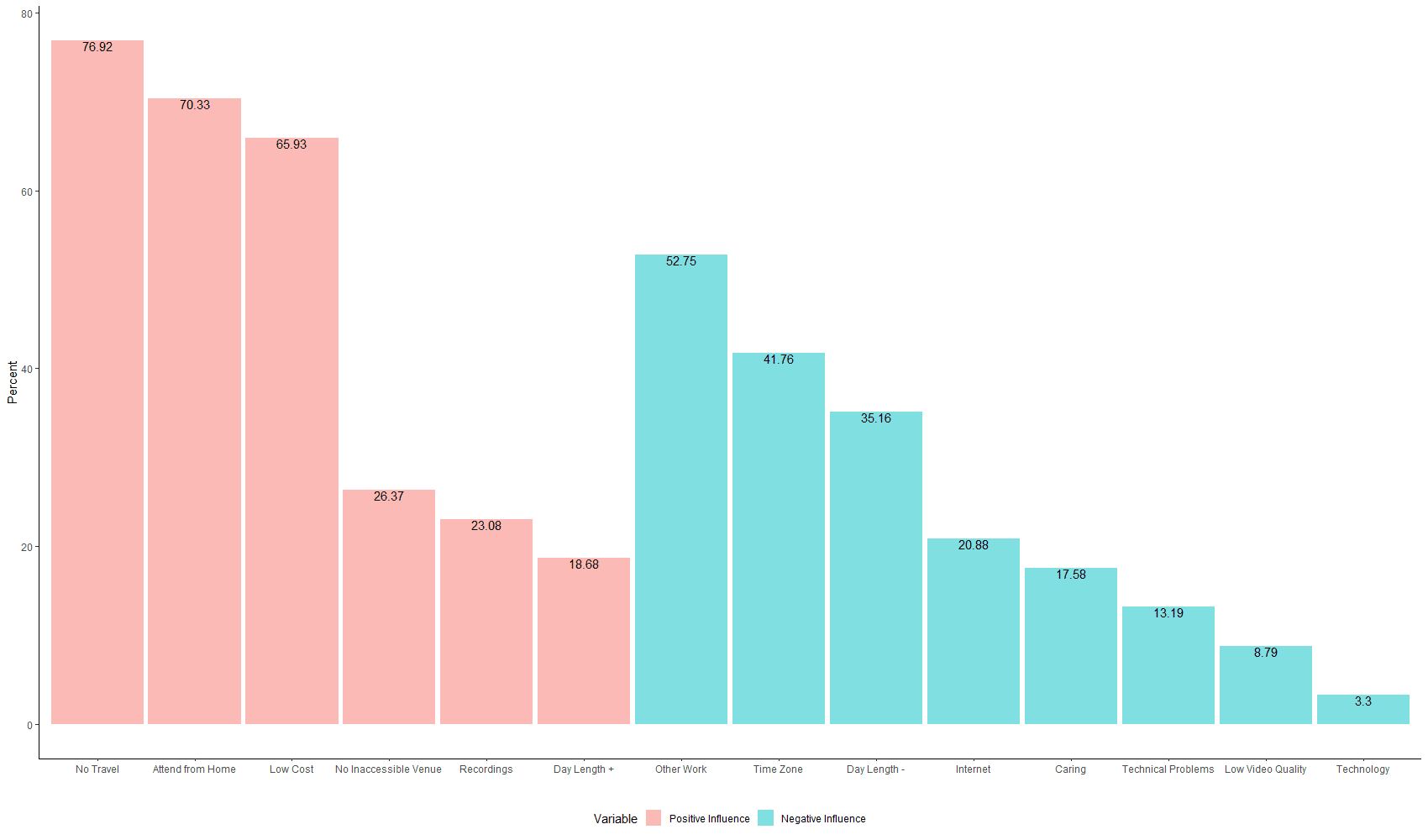

We also asked participants of the smaller conferences how various factors affected the accessibility of the online conferences (see Figure 1). The majority felt that reduced travel, working from home, and lower costs enabled them to attend, and some also cited not having to worry about venue accessibility and being able to watch recordings.

On the other hand, we also got an idea of factors that can limit attendance, such as time zone, conflict with other work, and day length. Some of these indicate special requirements for online conferences, such as having shorter days, longer and more frequent breaks, and scheduling to enable people from different time zones to join in. In supplementary material for the paper we also include some more specific tips for organisers of online conferences based on our own experience.

Figure 1. The percentage of participants that agree that the positive (left, pink bars) and negative (right, blue bars) factors affected their ability to participate in the conference.

It remains to be seen what will happen once lockdowns cease and borders open. We provide three reasons for continuing online conferences even after the pandemic has subsided.

First, there is the environmental justification. Online conferences drastically reduce pollution – up to 3,000 times – that otherwise would be produced by an in-person event. Most philosophers are committed to social justice and have accepted the findings and recommendations of the IPCC. Philosophers ought to limit harmful pollution produced by their academic activities, including conference participation, and off-set whatever pollution cannot be avoided.

Some philosophers have joined a growing number of scientists who refuse to fly to conferences, so-called conscientious climate change objectors. However, most major professional philosophy associations have not yet implemented measures to prevent and off-set carbon emissions. Some plan to discuss such measures, while for others it seems the issue is not even on the table. Many philosophers continue to engage in business as usual, a practice and attitude that they wholeheartedly despise when it comes from the mouths of climate change skeptics. Adopting the online-first model of conferences will allow philosophers to close the wide gap between their public defense of environmental causes and their actual actions.

The second group of reasons comprises issues of accessibility. Online conferences reduce the burden on scholars from less wealthy countries to seek visas for conference travel, as well as enabling participation for researchers with disabilities and scholars who have primary caregiving responsibilities. We hope that facilitating conference attendance from these groups will help to address some of the inequalities present in philosophical career progression.

The third rationale pertains to financial issues. Many universities have reported decreased budgets because of the pandemic. Budget shortfalls will negatively affect travel budgets, placing greater financial burdens on scholars to attend conferences. Given that some universities require faculty members to participate in conferences for the purpose of tenure or promotion, online conferences allow these scholars to fulfill their institutional expectations without experiencing a financial burden.

Philosophers and other academics should take the natural experiment that the pandemic brought about as an opportunity to build interdisciplinary work groups to study and establish best practices for online conferences, environmentally friendly and accessible in-person conferences, and adequate ways to offset carbon emissions.

We believe that philosophers ought to face up to the responsibility of tackling climate change and improving the lot of philosophers outside traditional conferencing areas, philosophers with disabilities, and primary caregivers. Doing so involves offering more online conferences, as well as implementing or continuing measures to offset emissions and improve accessibility for minorities in philosophy for both traditional and online meetings.

It is also a task for philosophers and other scientists to reckon with how to improve the quality of networking in online conferencing or to think of new ways to organise conferences such as combined online and in-person conferencing or multiple-site options that reduce distances travelled by individual researchers. Given the relative recency of online conferencing and the urgency of living up to sustainable and responsible research practices, it is perhaps time to approach critically our traditional ways of conferencing, information sharing and networking and to not only make use of online conferencing but also engage in the process of improving it.

Two thoughts:

1) The authors state that ‘the online format was not only seen [in their surveys] as a temporary replacement during acute crises like pandemics but as a legitimate alternative to in-person conferences (see Figure 1)’. That’s not how I read the data. Only 26% of their survey respondents think that online conferences are a satisfactory alternative to in-person conferences absent the COVID-19 crisis, with another 20% thinking that they’re a satisfactory alternative for small confererences. More than half the respondents who expressed an opinion (48% vs 46%) do not regard online conferences as a satisfactory substitute absent the crisis. And that’s from a survey among participants in an online conference, who probably skew more favorable towards online conferences than average or they wouldn’t be there. (Only 1% of survey participants say that online conferences are ‘never’ an acceptable substitute for in-person conferences; I assume that 1% won’t be attending any more online conferences!)

2) There’s nothing wrong with trying to find better ways of doing online networking. But I’m sceptical it will ever come close to the in-person alternative, just because of the more general experience of the pandemic. I imagine most people reading this site are in my situation: in person meetings with friends and family are drastically curtailed or eliminated entirely, but it’s easier than ever to stay in touch with people through Zoom and the like. And pretty much everyone I’ve talked to about this has my attitude towards it: *desperation* to get back to a situation where we can see people in person. I’m not sure I could really verbalise what’s so deficient about Zoom, or Teams, or GatherTown, compared to in-person meetings, but it’s just an empirical fact that they are really deficient. The mixture of shop-talk, informal idea-swapping, and plain chat that characterises academic networking isn’t identical to ordinary social conversation, but they have a lot in common.

The Australasian Association of Philosophy surveyed its members on this question. Members overwhelmingly (88%, from memory) preferred in person to on line.

sure but what are these preferences based on, anything that advances knowledge and not just careers/camaraderie?

would add that the virtual can also include the public who pay for much of this work but remain closed out by the paywall, couldn’t hurt to gain some public support in the coming austerity…

I thought that the utter dreadfulness of this year’s online conference season would finally put a halt to suggestions like in this post. Like David, I can’t quite articulate the precise issues, but the little conversations over coffee, lunch or dinner (and the ideas they sometimes spark) seemingly just cannot be replicated. Neither can just walking up to a speaker and toughing something out on a blackboard.

Admittedly, a little glimmer of enjoyment came from the fact that due to the low “entry cost” (if you will) of just tuning into a Zoom session, I did see some presentations that I would normally not have attended because they did not seem worth the time investment of attending in person. Some of these were surprisingly interesting. But I also missed some events I’d usually go to because I couldn’t stomach the dreariness of another Zoom call in that week. An amusing side-effect of the time zone differences was that for some events, I could just tune in after dinner and sit down with a bag of popcorn on the couch to enjoy some philosophy instead of some third-rate show on Netflix. Neither benefit, however, seems to be worth the loss of the in-person format.

The arguments presented in favour of “online-first” here seem weak. Climate: academic travel is a miniscule part of overall air travel, of which philosophy is a miniscule part. Many of my old classmates are now working in consulting and to them it is downright quaint that I am worried about flying 2-3 times a year whereas they get these numbers easily per month.

It is true that every bit helps to combat climate change, but pushing for this particular bit seems to stem from an idiosyncratic devaluation of conferences. Given how unfavourably commuting by car compares to a few flights per year, moving to working from home permanently would be far more efficent in cutting down CO2. But nobody advocates for this, as we all have painfully realised how bad online teaching is. But it is bad for the same reason as online conferences are bad. Pushing for the elimination of in-person conferences over the elimination of in-person departments seems to reveal that the authors don’t think conferences are all that important in the first place. But I think many would agree that they are a primary vehicle for knowledge exchange and progress in philosophy. If the authors don’t think this is very important, perhaps they don’t think philosophy is very important. Which is a fair position, I guess, but somewhat unexpected from professional philosophers.

Inequality cuts both ways. Graduates from “unranked” departments rely on the networking opportunities provided by informal chats with “big names” at small events. I have not seen these opportunities replicated in any way online (despite some valiant efforts). If everything is in-person, many might stay for the talk by the no-name grad student from the no-name school, but fewer might tune in for their pre-recorded talk.

The financial argument seems to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. The louder the voices are that claim we can and should move to online, the easier it will be for ever so money-hungry administrators to cut down budgets. This is also an argument against making conferences online-optional: it’s ammunition for the bean counters.

“Given how unfavourably commuting by car compares to a few flights per year, moving to working from home permanently would be far more efficent in cutting down CO2.”

I’m really not sure that this is true. Note for one thing that the aim is not to cut down on CO2; it’s to cut down on warming. And airplane emissions produce much more warming per molecule of carbon than almost anything else.

That said, it depends a bit on what you mean by “a few flights’. If you mean NY-Chicago, and the daily commute is like Westchester-Manhattan, then sure the driving might be worse. But if the commute is from the outskirts of a college town into campus, and the flights are trans-Atlantic or trans-Pacific, then the flights are much much worse.

Brian: I am by no means an expert, I just did a bit of googling. According to the EPA, an average car is worth about 4.6 tons of CO2 in a year. And according to a carbon calculator I found on google (I know…). A coast-to-coast roundtrip is about 1.1 tons (I used JFK-SFO) and a transatlantic one is about 1.6 tons. So getting rid of your car is worth 4 long domestic flights or 3 transatlatic ones. With three domestic and one international flight you are about on a par with owning a car. I can’t quickly pull up numbers on other factors.

Since I figure that most of us fly less than that (many commuting teachers, I suppose, don’t fly at all), eliminating commuting should be more effective all around. But I happily concede that there is a lot of back-of-the-envelope-ing in that argument. But then again, the same goes for the idea that stopping all conferences would make any sort of impact.

https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/greenhouse-gas-emissions-typical-passenger-vehicle

https://www.carbonfootprint.com

Isn’t this also an argument to replace classrooms with online teaching? Seems to be the same considerations, except at different scales. If so, I’d take that as a reductio against the position…

I’ve read many, many articles on this and similar subjects. Thank you to Justin Weinberg for writing up this post.

A bit of background, I have a photography business in Sydney that was providing photography specifically for B2B events. Like many people in the broader events sector 2020 came to a sudden business halt. I posted on this very website back in April 2020 here https://dailynous.com/2020/04/03/pandemic-conference-event-planning-2021/

Witnessing many events going online has been a blow but now in 2021 (and as Australia has by and large kept this nasty virus from running rampage) we’ve been able to work at a few events in late November and December (2020). Many of which have been carried out successfully with people in attendance and broadcast online to 5 cities.

Stats from the event, about 100 people at the conference and around 1500 online from other States that had borders shut or overseas who could not be in Sydney.

More about us here if you are so interested. (note most photos have people together 🙂 https://orlandosydney.com/

From my point of view and the feedback received form the event managers, it was a great success all round, the client was happy with the hybrid format. Having happy clients is key to confidence this early in the recovery cycle.

One common conversation from just about everyone we’ve engaged with online or in person is let’s do all we can to get back to in person events. Yes transport and early mornings can be a pain. But nothing online has beat meeting with humans for me and many others.

Heck, I’ve seen people inefficiently and ineffectually use video calls. Sometimes a simple email or phone would do 🙂

After seeing and working at hybrid conferences. I can see a great value add to our respective clients and attendees.

PS. Neil Levy – can you please provide a link to that survey?

Cheers

Orlando

I agree with all the comments about the issues with networking, social interaction and the like, and with the pessimism about the prospects for solving these issues. I also very much agree that, even all things considered, a world with no in-person academic conferences is not desirable. But I guess I don’t see why the choice is between all in-person or all online. There are existing events that I think make more sense in an online format. For example, some (not all) departmental speaker series. I imagine many departments are very constrained about who they can invite (and how many speakers they can invite) for financial reasons. Doing at least some sessions online avoids all these issues. Then there are events that only exist because of the shift. I can only speak for my corner of the field (epistemology), but there have been several things organised that wouldn’t have been possible in-person for various reasons. I’m sure some of these changes would have happened without the pandemic, but it has certainly hurried things along.

I think this lesson applies more generally. Is online teaching a replacement for in-person? No. But that doesn’t mean we haven’t learnt from the switch, or that there aren’t bits that are worth keeping going forward. I hope I’m not the only one who thinks their pre-recorded lectures are much better than their usual in-person lectures! A world where we upload a short-ish lecture before class, then use the class for discussion rather than lecturing, sure sounds good to me–both personally and pedagogically.

How depressing to see such hostility to such a reasonable proposal. After the climate-based catastrophes of the last year thousands of organizations in the private sector are now stepping up in a global effort to meet the IPCC target of halving global CO2 emissions by 2030, including by slashing their business-related aviation (see e.g. the We Mean Business coalition: https://www.wemeanbusinesscoalition.org/). So we’re in a situation in which e.g. the fashion industry is willing to change in the face of the climate emergency but not, it seems, philosophers. Not a good look.

I have mixed feelings about this. In terms of accessibility, I was able to ‘go’ to some conferences this year that I would not normally have been able to due to caring responsibilities. But because I was at home, I ended up missing talks and networking events partly because I was called on to help with dinner time/ bedtime. I suspect this is more likely to be an issue for women.

I was also limited to the number of talks I could attend because of zoom induced migraines. Finally, I found it a lot harder to focus on talks.

I also think that in these discussions we need to remember that the networking really is important for careers – given that grants require referees who aren’t at your institution and that career progression often requires you to have secured grants.

The climate change argument is really important. We all, including philosophers, need to change our ways of working and reduce emissions. But we need to recognise the costs, especially equity costs, and figure out how to manage them.

Replying to Kerry @12:57 –

I’m not sure I follow what’s ‘depressing’. I (and I think others) have serious concerns that online conferences fail to reproduce large aspects of what’s important about in-person conferences; I’ve said why. You can reasonably think either (a) that I’m just mistaken about the benefits of in-person vs. online, or (b) that academic conferences just aren’t that important to research and professional goals, so that it doesn’t matter much if they’re diminished, or (c) that while academic conferences are important, the impact on the climate emergency made by curtailing them outweighs that importance. I don’t agree with any of (a)-(c), but they’re clearly defensible – but at any rate they don’t seem so self-evident that it’s inherently depressing or a bad look for people to be arguing otherwise.

On the conferences:

There’s always been some sort of tradeoff between the costs of conference attendance (both financial, and in terms of personal travel time) and the benefits of conference attendance (both personal benefits for participants who get to spend some time in an interesting place with friends, and academic benefits of having a better networked group of people working on academic issues). Now that we all understand online events as a potential alternative, the cost/benefit analysis will work out somewhat differently for different events.

When the value of the event is mainly about discussion of new work that is not yet published, online events are a pretty good substitute, with some disadvantages and many advantages. When the value of the event is mainly about the informal networking that happens (which I think many people are too quick to discount as mere personal benefit, rather than a real benefit for the academic community) the in-person format is much, much better, particularly as the group getting together is larger.

This suggests to me that things like the APA, PSA, SPEP, still make a lot of sense to do in-person (and for climate and accessibility reasons, to do in cities with major hub airports, geographically close to the center of the community, so that most people can get there with only one take-off and landing, or a train ride, even if this is “unfair” to people who are based in geographically remote locations) while things like smaller specialized conferences, department colloquia, and work-in-progress brown-bag lunch series may be more natural to move online. (I think there’s an interesting case to be made that more colloquium series might no longer be organized by *department* and might be shared across institutions by specialist sub-fields of philosophy.)

On classes:

I’ve found that the pattern in classes is the opposite of conferences. Bigger classes (like intros) are more focused on intellectual material, while smaller classes (like advanced seminars) depend on more on informal interactions among the students for their value. My partner taught a 700-student intro to chemistry class last semester, and the online format was almost certainly much better than in person would have been, in terms of the amount of attention and access both to the professor and to each other that students had. I think it would not be unreasonable for universities (particularly ones like Texas A&M that have a commitment to ensuring that university education is available to many people) to do more intro classes online, and delay students arrival on campus to second year so that education can be in reach for more people, and so that people spend fewer years traveling between family home and campus several times a year.

On cars:

Many sites I’ve found have suggested that the climate impact of driving in a car that averages 1.4 occupants, and of flying in a commercial airplane with standard passenger loads, is about equal per passenger mile. Doing a 10 mile each way commute for 200 days would thus be comparable to about one and a half cross-country flights. If the average car is also used for shorter trips for errands and social events, and a few longer road trips, and if you also account for the carbon impacts of the manufacture of the car, this may end up pretty comparable to the figure listed above of overall car impact as comparable to four long-distance domestic flights per year.

For someone like me, that tries to cut down on personal car use, and who flies to a lot of events, that means that my personal impact from air travel is far greater than that from car use. Though if I’m right that there are benefits to the academic community of going to conferences, it doesn’t make sense to do the accounting on these in the same way, to attribute all the emissions to me (rather than to the community). (The same, of course, is true for the attribution of commuting costs to me rather than to the university, or the students, or the community at large that benefits from me and the students seeing each other in person rather than online.)

Replying to David @10.53 — I don’t think anyone, including the authors of the piece, is denying that there are goods associated with in-person meetings. What they state is that given the sizeable harms of putting on such meetings in comparison with their online counterparts — and implicit in this, of course, is that they involve flying people in for the purpose of the meeting, we’re not talking about meet-ups at the LSE with folk from Birmingham and Leeds etc — any decision to do so when we have a relativly workable alternative should be “limited and well-justified”. That just doesn’t strike me as controversial. Of course we are going to disagree about where the limits should lie (though of course there should be *some* limit — if morality didn’t require us to not have some nice things then we wouldn’t need it!). I for one am somewhat drawn (at the moment) to the sort of idea pondered by Kenny above — namely that there may be a rationale to still hold the PSA (partly) in person while most other stuff can be taken mostly online. I also very much like the idea of “hubs”, where local people get together in groups and have those groups meet on Zoom. But I see no justification whatsoever for (what seems to be) your claim that there should be no curtails whatsoever on academic aviation for the sake of its supposed goods.

One thing that I do find depressing about how these conversations are going (and I’ve been having quite a few over the last few months) is how open other fields are to the idea compared to ours. I could share plenty of info from scientific contexts but just look at this from the History of Science Society (which the PSA used to partner with). They, as other organizations, are way ahead of the curve here. And yet the ask we need to engage in seems so philosophical: carefully reflect on our experience, understand its value, and weight the relevant goods against the harms in a way that optimizes fairness for everyone.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-for-the-history-of-science/article/innovation-in-a-crisis-rethinking-conferences-and-scholarship-in-a-pandemic-and-climate-emergency/601948CB0B684F833AC3E96643E46F2C#.X7TlXVImv4A.twitter

Finally David (if you are still there!), and more constructively: I completely agree that we need to think about the potential harms caused to early-career people by any change in extant practice. But here there are also huge opportunities. One thing that has been a real plus point of the pandemic is the way we’ve been able to do reading groups including participants from different campuses. Has that been a way for you to connect with early career people who would benefit from interactions with someone so established as respected as you? While not as fun as having a big boozy meal together, hasn’t there been information in these sorts of experiences that might help you advance the careers of those whom you think deserve it?

More generally, very often in my experience more established people justify in-person conferences by defending their value to the less established. We need to hear from both sides of the equation here, and (in our heads at least) exhaust the alternatives for how these goods could be preserved or simulated in a less carbon-intensive environment.

@Kenny Pearce: possibly this just reflects the differences between subfields, but I don’t at all agree that ‘smaller specialized conferences’ move online more readily than big meetings. In the Before Times I went to lots of small specialized conferences and not many large meetings, largely because I found the former a lot more valuable – and at least 70% of the value of the small conferences to me was informal conversations with participants. The talks are necessary as a frame on which to hang the discussion structure, but they’re not the main point. I spent today and yesterday at a wonderful, beautifully organised and structured, small online conference on the interpretation of quantum mechanics – and it still didn’t hold a candle to similar meetings I used to go to in-person. (And I’m talking here about academic benefits, not personal benefits. I agree completely that ‘networking’ – which largely means informal research discussions – is an academic and scholarly benefit.)

@Kerry 8:10: I suppose the root of the disagreement is ‘relatively workable alternative’. I don’t think online conferences remotely succeed in substituting for in-person meetings. If in-person meetings are impossible – either because of the pandemic, or because they’re morally unacceptable on climate-change grounds – then sure, let’s salvage what we can by Zoom. But that says nothing about whether Zoom is actually a workable substitute. (Similarly, if we can’t do Zoom, let’s try to correspond as much as we can by email; if we can’t do email, let’s exchange letters… etc.)

Should there be ‘no curtails whatsoever on academic aviation for the sake of its supposed goods’? I haven’t argued that. It depends how valuable you actually think conferences are, and what you think about the importance of curtailing aviation to address the climate emergency. I’m arguing that Zoom doesn’t much affect that calculus, because I think Zoom conferences are such poor substitutes for in-person conferences. Take the pandemic as an analogy: because of COVID-19, we shouldn’t be meeting in person, and so there should be no in-person conferences; it’s great if Zoom lets us recover some small fragments of the benefit of in-person conferences, but even if there was no Zoom, we still shouldn’t have in-person conferences. (For what it’s worth, I’m sceptical of the value of curtailing air travel as a route to address climate change, but if you persuade me otherwise, Zoom still wouldn’t matter – I’d just start advocating that we don’t have conferences.)

@Kerry 8:15 – to be honest, having a new baby in the middle of the pandemic (something I think you may have some experience of yourself 🙂 ) means I’ve not really explored those issues as much as I could. (In practice – as somebody who travels a lot and spends many hours at conferences talking to people at all levels of experience – I’ve been vastly less useful to junior scholars this year than in previous years, but I can’t really know how that would have been absent family issues.) But to address your general point: I’m not appealing to the value of conferences to the less-established; I’m appealing to their value to scholarship. But the difference may be subtle: on a longer-term view, of course it matters that junior people are recognized and get a chance to develop their ideas and to bring them to the attention of senior people.

That Zoom meetings, even (by their own standards) successful ones, fail to even ‘remotely succeed’ in simulating the benefits of in-person ones strikes me as an extreme view. But it’s your view, and I’m of course not in a position to say that it’s not the correct value judgement! As an empirical fact about me however I’m surprised by this view — no doubt since I’m surrounded by people who’ve expressed so much enthusiasm, on both moral and personal grounds, for the fact they don’t have to get on planes to (supposedly) do their job anymore. It would be good to have more of a sense of how the community at large feels about the issue. We’re lucky then that the PSA plans shortly to administer a survey of members on how they feel about this issue. Lots to chew on there I’m sure.

It’s been suggested here (and elsewhere) that it is important for us to return as soon as possible to the old ‘norm’ of holding our conferences in-person because we need this kind of in-person interaction for purposes of securing support from other academics for our work, including acquiring reference writers. But it’s important to recognize that the in-person method of securing support isn’t a gold-standard but has significant shortcomings of its own, hence doesn’t provide the kind of overwhelming reason for academics to return to in-person conferences that rely heavily upon air travel for people to attend.

So, for example, whether a senior and more junior person ‘click’ at a conference may depend on lots of personal factors which have nothing to do with whether the junior person is doing good work that merits support. When things go well it may be because of superficial features to do with how someone appears or their sharing a sense of humour or an interest in football (or whatever it might be) and when things don’t go well that may be because there are prejudices at work or just because someone is nervous or prefers another sport or doesn’t like sport. It may even be the case that a senior philosopher simply isn’t open to this kind of interaction at conferences but sees the conference as a time to catch up with old friends and enjoy the food and wine or only wants to hear the papers and doesn’t want to socialise.

It’s even worse for people who can’t attend conferences for financial reasons, caring responsibilities, disabilities or, a significant new category: the growing number of academics who as a matter of moral conscience don’t want to fly regularly anymore, who are thereby cut off from securing support for their work by this route. It’s also worth pointing out this isn’t just an issue for junior philosophers. There are plenty of mid-career and late-career academics who want to apply for grants, change jobs or get promoted but their original referees have retired or died.

The upshot is that whilst virtual conferences aren’t ideal in all respects, because many of us enjoy in-person interaction, in-person conferences aren’t ideal in all respects either, never mind the environmental costs, and it may be that having more virtual interaction with one another opens doors for many philosophers who would otherwise be excluded or disfavoured by the old ‘norm’ whilst also cutting back on the environmental costs of our research.

@David Jones – I don’t mean to claim that the online version of a specialist conference is particularly close to that of the in-person version. I just mean to claim that more is salvageable than there is for something like the APA. I’m going to a few APA talks this week, and getting something out of it. But I think the ratio is lower than some smaller specialist conferences and workshops I’ve been attending.

That said, I probably haven’t drawn the line exactly right – it’s not exactly size and specialization that make the difference, but probably something further about the organization style, and community, and so on.

I expect that in the end, there will be some classes of events that in the past have occurred mainly via travel, that in the future will mainly occur online (and more of them total will likely occur because of their low cost, even if each online one is less valuable than each of the travel ones had been). There will be other classes of events that will still mainly occur via travel (and the number of those will likely decrease). The most pressing question is probably to figure out which are which.

I tend to agree with David Wallace that Zoom is not even close to reproducing some important aspects of an in-person conference experience. But I think Zoom is a more reasonably adequate substitute for departmental colloquia, class visits, and I think possibly better than the in person version for job searches (though I haven’t been through a complete zoom search experience so I might change my mind about that). I don’t know if others agree. But if they do, perhaps a smaller but still significant step would be to move most of those events online and keep a healthy number of in person conferences in place (I am however very much in favour of also having a healthy number of online conferences given that there are some obvious advantages for those as well).

As one of the authors of this post and the paper it’s based on, I’d like to thank everyone for their attention to this pressing issue!

We acknowledge that online conferences do have downsides, especially when it comes to the experience of networking. An in-person conference that is planned to be maximally accessible, that provides ample opportunity for networking (ideally more targeted and effective than merely milling around in a foyer trying to sidle into a group of professors to talk to that one person who you want to be a referee on a grant), and that offers options for online participation for those unable or unwilling to travel would, we think, be a candidate for a well-justified departure from an online default.

There are also limitations on online conferences in terms of zoom fatigue and caring responsibilities, as Fiona Woollard reports from her own experience. We make a suggestion in the paper that online conferences should still offer funding for childcare, so that (post-pandemic, when childcare is functioning again) caregivers don’t have to trade-off networking with cooking dinner and putting their kids to bed. In addition, we recommend that online conferences have shorter schedules to deal with zoom fatigue – obviously a limitation that some researchers view as a serious restriction in comparison to in-person conferences.

The option of local hubs for conferences seems to have worked in some other disciplines, and we think it would be worth trying out in philosophy too, at least for larger fields or national associations. However, it is important to note that such formats often require more expensive technology and can be more complicated to organise than single-venue or online events.

I welcome the point from Kerry McKenzie about recognising alternative ways to network and promote junior researchers, including smaller more regular formats such as online reading groups and colloquia. These do indeed seem to facilitate networking online in a more natural way than some online conference formats.

Finally, it is worth drawing attention to one of the points in our paper, which is a call for more research on this topic. Our surveys indicated that online conferences were well received by those who participated in them, albeit during a pandemic. But, as some people mentioned in their comments and as we acknowledge in the paper, these responses are likely to be somewhat biased both because they occur in a pandemic and because those who really hate online conferences wouldn’t have signed up in the first place. We hope that we will be seeing more results from empirical research on upcoming online conferences and also from the philosophy community in general. This will help us to move beyond personal opinions and experiences towards a picture of the general attitudes in the community towards online conferences as well as the variation across the community in terms of needs and preferences for meeting formats.

@ Rose Trappes, 10.16am: thanks for writing this piece! Regarding your past point, the PSA is about to survey their membership on precisely these issues and will be reporting results to DN in due course. I absolutely agree that what is needed now is a sense of where the community stands in general, as this is of course something of a collective action problem.

People might also like to note that Philosophers for Sustainability is running a (virtual!) conference on these issues in June, which will discuss, among other things, our carbon emissions as an urgent aspect of our professional research ethics. http://www.philosophersforsustainability.com/conference2021/

Regarding Zoom fatigue: absolutely it is real! But so is jet-lag and at least when I’m at home and feeling fatigued I can go for a lie-down 🙂

Lots more to say, but I’ll note in closing that the APA and the PSA have now endorsed the Sustainability Guidelines of Philosophers for Sustainability. These include an urge that philosophers reduce high-emissions travel where possible, so in a sense as a profession we have already ‘signed up’ to your proposal (and now I’ll let this descend into a discussion of contractualism!)

Thanks again for the article and I hope to get to work with you in some capacity soon.

I want to push back on worries about not being able to network in the traditional way.

First, if everyone is no longer able to network in the traditional way then no longer doing this doesn’t disadvantage anyone in particular.

Second, one part of the apparatus that keeps disabled people out of philosophy is precisely being excluded from traditional networking events. So not only does not having these events not disadvantage anyone in particular, it also may level the playing field for disabled philosophers who are typically excluded from such events.

There’s a lot going on in this interesting conversation, but let me pick out two points.

1) If the value of ‘networking’ is career advancement, then I agree that the value of networking in conferences is questionable, not least for Robert Chapman’s reason: it’s zero-sum. But I’m assuming that the main purpose of conferences in general, and networking in particular, is scholarship. Networking is valuable because it disseminates and develops ideas, because it leads to collaboration, and because it cuts across geographical divides that can slow and silo research. If I were to be persuaded that our research is not intrinsically that valuable and the main putative reason for conferences is that they play a role in our hiring and advancement structure, then I might well come around to the view that we should stop having them. But I would probably also explore the prospects for doing something else with my life – it’s fairly pointless to be a research academic if you don’t think your research is worthwhile.

2) Conferences basically do three (research-relevant) things: they let people present new work, they facilitate discussion of that work in the Q&A, and they facilitate more informal discussions among the participants. In my view, that’s an increasing order of importance: to me, the main point of conferences is the various informal connections they provide, and the formal stuff is a (necessary!) frame on which it hangs. From that perspective, conferences that don’t manage to make the informal connections work* aren’t usually worth going to, and (to pick up a point from Fraser McBride) , if ‘a senior philosopher simply isn’t open to this kind of interaction at conferences but sees the conference as a time to catch up with old friends and enjoy the food and wine or only wants to hear the papers and doesn’t want to socialize’ then it was a mistake to invite them and they shouldn’t be invited next time. (When I attend a conference – especially if I’m an invited speaker and my costs are covered – I take it as read that part of the deal is that I participate pretty actively in the discussions, in and out of talks.) But it is defensible to reverse my order of importance, so that the real point of a conference is the presentation of new work, the secondary point is formal Q&A feedback on that work, and the informal bit is just icing on the cake. From that perspective – which, for all I know, actually applies to lots of conferences, just not the ones I go to – the ‘move it online’ argument is pretty persuasive, on cost and time grounds alone whatever one thinks of the climate-change case.

*It’s not that difficult. Choose a conference theme that’s cohesive enough that participants have lots to talk about; organize a schedule that has long coffee breaks and doesn’t try to squeeze too many talks in; invite people who you know will work to participate fully (or at least: don’t invite people who you know won’t work to participate fully!)

How about both! Make all future in-person conferences streaming on Zoom. That could be the host’s job. Simply set up a Zoom meeting on your phone or laptop and aim at the speaker. The better the conference quality, the more seriously it’ll take its Zoom set-up. This won’t address the climate issue as much, but it’ll help with the other concerns (accessibility and financial).