Citing (and Thanking) the Referees at the Journal that Rejected You, Part 2

“We argue that when an author’s work is published, the author should thank the reviewers whose comments improved the paper regardless of whether those reviewers’ journals rejected or accepted the work.”

That’s Joona Räsänen (Oslo) and Pekka Louhiala (Helsinki) in “Should Acknowledgments in Published Academic Articles Include Gratitude for Reviewers Who Reviewed for Journals that Rejected Those Articles?“, a new article published in Theoria.

Here’s the abstract of the paper:

It is a common practice for authors of an academic work to thank the anonymous reviewers at the journal that is publishing it. Allegedly, scholars thank the reviewers because their comments improved the paper and thanking them is a proper way to show gratitude to them. Yet often, a paper that is eventually accepted by one journal is first rejected by other journals, and even though those journals’ reviewers also supply comments that improve the quality of the work, those reviewers are not customarily thanked. We contacted prominent scholars in bioethics and philosophy of medicine and asked whether thanking such reviewers would be a welcome trend. Having received responses from 107 scholars, we discuss the suggested proposal in light of both philosophical argument and the results of this survey. We argue that when an author’s work is published, the author should thank the reviewers whose comments improved the paper regardless of whether those reviewers’ journals rejected or accepted the work. That is because scholars should show gratitude to those who deserve it, and those whose comments improved the paper deserve gratitude. We also consider objections against this practice raised by scholars and show why they are not entirely persuasive.

Readers may recall from last year a post on this very subject, featuring an email calling for a “new norm” in academia to “acknowledge the help of all referees, at all of the journals to which you have sent your paper, if their help was of the sort that you would acknowledge from the journal that published it.”

Räsänen and Louhiala’s argument is simple:

Premise 1. The author should thank all whose comments improved the paper.

Premise 2. Comments from (some of) the reviewers at journals that rejected the paper improved the paper.

Conclusion. The author should thank (some of) the reviewers at the journals that rejected the paper.

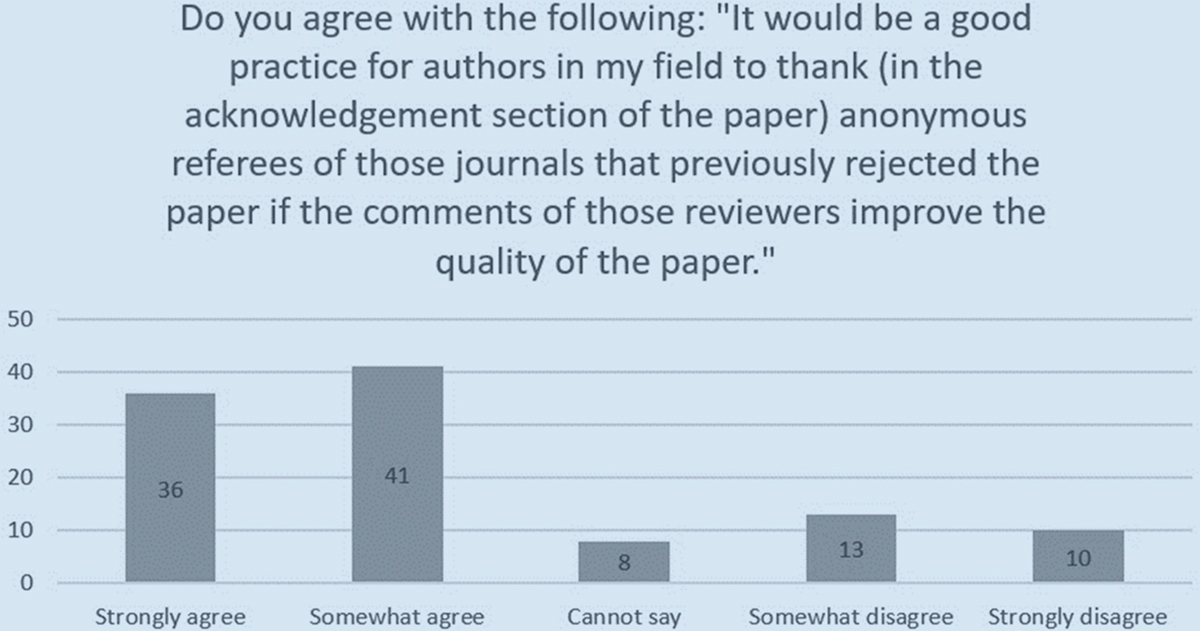

Most of the scholars they surveyed seem to agree with their proposal:

[Figure 1 from Räsänen & Louhiala, “Should Acknowledgments in Published Academic Articles Include Gratitude for Reviewers Who Reviewed for Journals that Rejected Those Articles?”]

I was one of the anonymous reviewers of this manuscript. To authors Joona Räsänen and Pekka Louhiala, I say “You are welcome,” and congratulations on the publication.

The author’s argue: “we think it is unlikely, that those who would suffer the most for showing the rejection history of journals (young scholars) actually care that much about journal prestige”

They then have a footnote: That said, it could also be that younger scholars care about journal rankings more than senior scholars because young scholars do not have permanent jobs and they think (regardless of whether it is true) that to get a permanent job one needs publications in prestigious journals. We thank Caj Strandberg for this remark

I think Caj Strandberg is right on the money here. At least here in the UK, having publications in prestigious journals dramatically increases your chance of getting any academic job at all and especially a permanent job.

More generally, I think that given we cannot list the reviewers by name, there is not enough benefit in the extra specificity of adding the journal name to overcome the potential costs of doing so. I’m going to continue with my current practice which is to acknowledge directly whenever a part of my paper has improved due to an anonymous referee by saying e.g. “Thank you to the anonymous reviewer whose comments lead me to ……” I will also include a thank you to ‘the anonymous referees who gave me helpful feedback’ in the acknowledgments.

‘Thanks to big shot A (my dissertation advisor), big shot B (on my committee), big shot C (who I met once on line at a hotel Starbucks at a conference), my friends from graduate school who have fancy jobs D, E, and F, and, especially, to the reviewers and editors for this essay’.

It’s amazing to me that we spend all our public-facing efforts trying to argue for the intrinsic value or practical importance of philosophy, and then researchers spend their precious time investigating such important questions as this.

This is such a ridiculous comment.

What is it about this topic in particular that prompts this reaction on your part? And what, in your view, are philosophers obliged to spend their time working on? Do most philosophers work on the topics you deem worthy of our attention? My bet is that they don’t (perhaps not even yourself).

Moreover, I would say that the vast, overwhelming majority of published work in philosophy is on relatively unimportant issues. Would you make the same comment under a post about an article on some obscure historical figure? Or under a post about abstract issues in metaphysics? What about folks working on formal semantics? Or how about <insert pretty much every topic that people sometimes work on>?

For my part, I think that philosophers (and other academics more generally) spend far too little time grappling with issues I think are truly important. At the same time, I think it is permissible for them to occasionally devote their time to working on issues they want to work on for whatever reason, no matter the importance. If people want to work on topics in applied ethics such as in the above post (or philosophy of language, or metaphysics, or whatever), who are you to say they shouldn’t?

Incidentally, if the underlying idea here is that we each have a duty to devote ourselves to work that does the most good, that may be true, but becoming a grad student in philosophy (like you or I) is likely not the best way to do that…

I think there are plausible arguments on the intrinsic value of investigating questions important to our understanding of existence, the human condition, etc., such as those in metaphysics, philosophy of religion, mind, etc. I think there is also practical value in investigating applied topics, including applied topics in philosophy of science (e.g. how publication norms advance certain research paradigms).

I do not think there are plausible arguments generally to justify research on the inside baseball of publishing relating to the most obscure and unimportant features of publishing. I do not think the authors blameworthy for doing this (and so am not making any claims about some wide-ranging ‘duty’). At worst, I think it counter to the mission of our profession, and damaging to its advancement; at best, it is benign.

Further, I was not primarily trying to signal what is ‘worthy of *my* attention.’ I was trying to remark on what is worthy of anyone’s attention.

I will not write a treatise here to draw the exact line between what is or what is not important. I intended only to signal that this particular topic seems firmly on a particular side of that line.

Well, I’m obviously not asking you for a treatise. Absent an account of these plausible arguments you have in mind, though, I’m not sure why we should take seriously the claim that these philosophers are wasting their time writing on unimportant topics. It’s very easy to *say* you have plausible arguments for the intrinsic value of all sorts of abstract issues in philosophy, together with plausible arguments for why their work on this topic is a waste of time. But my guess is that such arguments would in fact be quite controversial, and that philosophers would disagree about what sort of work is and isn’t worthwhile or intrinsically valuable.

Something similar applies to your remark that you’re “not primarily trying to signal what is ‘worthy of *my* attention.’ I was trying to remark on what is worthy of anyone’s attention.” Of course you’re doing the latter. But again, questions regarding what is worthy of anyone’s attention are going to be controversial, and you don’t speak for everybody in the profession on that front. So while you are attempting to remark on what is worthy of *anyone’s* attention, they’re still *your* comments and *your* ideas in that regard.

As I already mentioned, I agree that this particular work engages with a topic that, to me at least, seems quite unimportant. But I don’t know why that by itself warrants anonymous, sarcastic comments online like your initial comment (that the authors will likely see, of course, not they they’ll care).

Grad Student4 is exactly right. Suppose (as Fiona Woolard suggests) you simply wrote “an anonymous referee helped me sharpen this argument.” That’s a tiny increase in virtue, because while you don’t take sole credit, you’re not increasing anybody’s credit score either. Is it worth getting all huffy about somebody who thinks it’s not a big deal? I don’t see it.

This debate here is at an impasse. Both commentators can go on ad Infinitum about what is pressing or important in philosophy. I will avoid that and instead focus on the consequence it has on readers of articles.

As such, if you read the article, the author said the reader will see the acknowledgement. In a profession that values so much armchair philosophy and solipsism, it’s a good to show thanks to reviewers because it tells us that philosophers are people with flaws too. And that good work can come from the advice of others. Students and grad students will see and think “oh wow, this author received a lot of help. I guess there’s nothing wrong with asking for help or receiving critical feedback.” A lot of us who start off doing philosophy are afraid to be criticized. It’s good to see senior and seasoned philosophers still getting help and feedback from others. At least, we’ll be less afraid knowing we’re not alone.

In sum, one positive consequence of such acknowledgment is that readers e.g. students will feel more comfortable asking for or receiving critical feedback. This possible because of such transparency and epistemic humility. I can only imagine the level of anxiety and pressure in philosophy and on philosophers and students if *nobody* showed any gratitude/appreciation and pretends that he or she is naturally that good at philosophy or at least, expected to be that good.

“the author should thank the reviewers whose comments improved its quality regardless of whether the journals for which those colleagues were reviewing rejected or accepted the paper. That is because we should show our gratitude to all those who deserve it, and those whose comments improved the quality of our work deserve our gratitude. Our suggestion would thus be against current norms in publishing.”

Is it ‘a current norm of publishing’? I don’t think so (see Respondent 99 and 105). I am sure I am not the only one who has written: ‘Thanks are also due to various reviewers of various journals.’ This obviously includes the reviewers who rejected my paper. And as Fiona Woollard noted, we can always give credit to a helpful reviewer when discussing a specific issue in the text.

Without the empirical side, the paper wouldn’t be that interesting; it tells us what people think. But the example given to illustrate the question was unfortunate: ‘I would like to thank the anonymous referees of journals A, B and C…’ Understandably, authors will be reluctant to list the particular journals who rejected their paper. There is no need to mention the names of journals, just thank ‘the anonymous referees who improved the quality of the paper’. Interestingly, the authors think this is ‘too vague’ (section 6). They think the more information you give (i.e. the journal name) the better. But reviewers are anonymous; I don’t think there will be many reviewers who are so desperate for acknowledgements that they will keep an eye out for the progress of the paper they reviewed – they will have better things to do.

Most primary school children would agree, and could have come up with the same conclusion as the authors: we should show gratitude to those who helped us (i.e. those who deserve it). I ask myself: should this paper have been written? And should it have been published?

The value of gratitude stems from the fact that it is freely given, rather than expected or enforced. You help others because they need help, because they are close to us, etc. But we don’t do it because we expect or hope for gratitude in return. In this context nobody is ‘owed a debt’ (5.11).

If you ask another for help, and they help you, then the case for showing gratitude is much stronger than in the journal reviewers case. I didn’t ask for the help of reviewers; all I wanted is their decision to publish or not. They often freely give their help (through constructive criticism), but their – hypothetical – claim for showing gratitude would be much weaker than if I had asked for their help.

A much more interesting question is connected to the pressure to publish in academia today: should authors (and the scholarly community) be grateful to reviewers who reject their poorly argued or, horribile dictu, pointless papers?

Thanks. Based on the feedback we have received, half of our readers seem to think what we say is wrong, and the other half think what we say is so obviously right that is not worth saying. You were able to combine both!

While I don’t think your article will lead to a wide change of practices in the profession, don’t get to beat down by those saying that this is pointless, this a small but nonetheless worthwhile advance that is the hallmark of science. And who knows this might factor into greater peer review reform.

The difficulty of commenters here hinges on mentioning journals that rejected you in the acknowledgement but I am not sure about the harm claim given the standards of the field at the moment for publishing anyways, especially since really useful comments would not span the whole list of rejections.

Do we need a whole paper arguing it’s nice to show gratitude to people who help you, if possible? Should we have a paper about what gratitude is due to people who hold the door open for you, or who smile politely at you, or who give you a stray compliment, or who offer a dash of advice in passing etc. etc.? To be clear, I ask whether we should have a paper for EACH one of these cases, not on the issue of gratitude more generally (which could well be interesting), since this paper focuses in on just one case.

It seems to me that this question answers itself, since it in turn raises the next obvious question, which is: why don’t we already have papers on holding doors open, and compliments, and so on? The reason is that philosophers wrote this paper, and, narcissists as we all naturally tend to be, philosophers will tend to write about the minutia of day-to-day life that most affects their little egos, like the norms of little thank-yous in footnotes to journal articles. If there were an Onion news for the profession of philosophy, this could very well be a headline: “Ethics professor writes article about how it’s super mean and unethical when people don’t thank ethics professors for all the great stuff they do”

There’s a disanalogy here, which is that there are many reasons for thinking that the norms of academic credit-giving need to be rethought and reformed. No such reasons exist for the other examples you give of trivial norms of gratitude.

Grad Stu: You wrote, “why don’t we already have papers on holding doors open, and compliments, and so on?”

The answer is that these are already used as thought experiments or examples within the philosophy of gratitude literature already.

For more info please visit: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/gratitude/

As for this particular research article, I suppose it can be relegated as an example or thought experiment about gratitude in general.

However, because those above examples are so common to everyday life and because they are often used as examples or thought experiments within the gratitude literature, it would *redundant* to write about them specifically.

Since this particular practice of thanking referees is an extremely niche gesture compared to what ordinary citizens do in their daily lives AND because it is rarely (or hasn’t ever been) used as an example or thought experiment in the gratitude literature, it’s up for grabs I suppose.

Some people in the comments have said that this article is unimportant or at least trivial. I am sympathetic, but I still find such arguments unconvincing for reasons I have already provided in the comments above. As well, I also think people should write about what they’re passionate about so long as they also produce works that are “pressing” as well. I like to approach the middle way in regards to the debate about what is more important to publish in philosophy. Indeed, I’m so enmeshed in virtue ethics that I forget what I study means to outsiders. I think a lot of us can relate.

However, I do want to shed light on the (unsurprising) causes of such sentiments of people who think certain articles are unimportant or trivial in general. This is not targeted at this article per se. There are *at least* two causes: 1) philosophers’ pressure to publish and 2) philosophy’s obsession and expectation for originality.

When these two causes combine, the (unsurprising) result is that you’ll get *some* articles that are deemed unimportant or trivial (to some or many people ) because the authors were *scrambling* to produce something new or “novel” under the pressure to publish X amount of articles per year. Therefore, before we are quick to judge whether an article is unimportant or trivial, we should understand the background conditions that gave rise to existence such articles in the first place.

One thing I would really like to see implemented is a way for authors to (anonymously) thank referees for their comments. I have received some incredibly careful, conscientious and useful comments over the years, including on papers that have been rejected. I always felt bad that I could not express gratitude to these referees, who must feel a bit like they are spending care and effort to help a void. I also think that this small change would make it more rewarding for referees to do the work, which would improve the whole process. The only downside I can see is that there might become social norms to express gratitude, which could be awkward if you don’t think the reviews are good, or that authors could use the form to communicate with the referees in less constructive ways. Perhaps it could go through a brief check by the editors, but they are already overworked, I suppose.