What Is Learned from 70,000 Responses to Trolley Scenarios?

A team of researchers has reported on its collection and analysis of 70,000 responses to three scenarios that frequently comprise versions of the trolley problem.

Appearing in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, “Universals and variations in moral decisions made in 42 countries by 70,000 participants” lays out the results of the massive study that collected the responses, in ten languages, from 42 countries. The study was conducted by (Exeter, MIT), , , , and

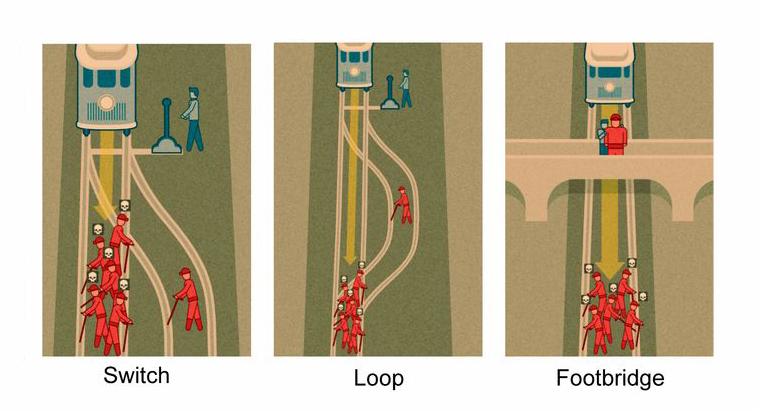

The participants were confronted with three hypothetical scenarios in which a trolley will soon roll over and kill five workers unless the participant chooses to intervene and sacrifice the life of one other worker.

In “Switch” (aka “Bystander”) the participant’s options are to do nothing, in which case the five workers are killed by the trolley, or to pull a lever that diverts the trolley onto a spur track on which one worker is stuck, killing that one worker. In “Footbridge,” the participant’s options are to do nothing, in which case the five workers get hit by the trolley and die, or push a large person off of a bridge above the track so that his body stops the trolley, killing him but saving the others. In Loop, the participant’s options are to do nothing, in which case the five workers are killed by the trolley, or to pull a lever that diverts the trolley onto a side track that connects back up to the main line just before the location of the workers; ordinarily, this would do nothing to save them, but in this scenario there is a large person on that side track, and if the trolley hits him, it will stop before it gets back to the main line, killing the one on that track but saving the five on the main line.

What did the researchers find? First, “Participants endorsed sacrifice more for Switch (country-level average: 81%) than for Loop (country-level average: 72%), and for Loop more than for Footbridge (country-level average: 51%).” The authors say that “data suggested that people from different cultures displayed a remarkable qualitative regularity, the Switch–Loop–Footbridge ordered pattern of preferences.”

Second, the data “also suggested that people from different cultures displayed quantitative variations in the exact degree to which they endorsed sacrifice in each of these scenarios.” This finding concerned relational mobility. Relational mobility refers to “how much freedom and opportunity a society or social context affords individuals to choose and dispose of interpersonal relationships based on personal preference. The researchers found a positive correlation “between relational mobility and the propensity to endorse sacrifice in each scenario variant.” Commenting on this finding, the authors write:

holding attitudes that put one at social risk is especially costly in low relational mobility societies, where alienating one’s current social partners is harder to recover from. This cost is likely lower (although not absent) in high relational mobility societies, as they offer abundant options to find new, like-minded partners. Accordingly, people in low relational mobility societies may be less likely to express and even hold attitudes that send a negative social signal. Endorsing sacrifice in the trolley problem is just such an attitude. Recent research has shown that people who endorse sacrifice in the trolley problem are perceived as less trustworthy, and less likely to be chosen as social partners. As a consequence, low relational mobility societies may feature more acute pressure against holding this unpopular opinion. Although it is possible that this pressure would discourage people who hold socially risky positions from expressing them, it could also change people’s attitudes, making certain ideas morally “unthinkable.”

The researchers have made their data publicly available on the Open Science Framework for others to examine and use.

Here’s one question for us: What, if anything, should philosophers take away from this study?

Related: “Trolley Problems: You’re Doing It All Wrong“, “On Trolley Problems“

More evidence for the claim that Steve Stich and I argued for against Knobe. For memory: http://dailynous.com/2019/12/02/philosophical-intuitions-demographic-differences/

Hi Edouard,

Really looking forward to continuing this conversation! I have a slightly different take on the relevance of this study to our debate, and I’d love to hear more about your thoughts on it.

In my previous paper, I suggested that one surprising finding coming out of existing empirical studies was that the effects experimental philosophers find in one population seem so often to arise in other populations as well. Time and time again, we run an experiment showing a difference between conditions in the application of some concept (knowledge, intention, personal identity,, causation, …), and we then find that this same difference arises in numerous other cultures and also in very young children. This robustness calls for an explanation. For example, it might be explained by theories that posit innate cognitive mechanisms that explain the difference between conditions.

This new paper takes a pattern that was observed in Western participants (Switch > Loop > Footbridge) and shows that this pattern is extremely robust, arising also in numerous other cultures. The robustness of this pattern calls out for explanation, and in this particular case, there actually are theories that provide such an explanation. These theories say that there is an innate cognitive mechanism explaining that pattern (though of course they also allow for cultural learning to affect people’s moral judgments). The present study seems to provide evidence in favor of theories broadly along those lines.

The point I was making is that we also observe this sort of pattern in lots of other areas, such as in intuitions about knowledge, intention, personal identity, causation, and so forth. In many of those other areas, we don’t at present have worked-out theories that explain patterns in people’s intuitions in terms of innate cognitive mechanisms. So the robustness observed in those other areas is quite surprising and calls for explanation. One approach to explaining it would be to develop theories that resemble the theories researchers have already developed to explain patterns in trolley problem intuitions.

Are you seeing this in a different way? Suppose that I previously assigned some credence to the proposition that there was a surprising robustness in certain patterns of people’s trolley problem intuitions that called for some special explanation, e.g., in terms of an innate mechanism. Are you thinking that I should now *decrease* my credence in that proposition in light of the cultural differences observed in this new study?

I was curious about this as well, but, like Josh, had assumed the primary relevance would go in the opposite direction – in supporting the contention that intuitions are surprisingly robust across cultures. Edouard, I’d be curious to hear more about your take on this and the disagreement between you and Josh. I’m wondering if the disagreement is being driven by whether we should care about (i) whether moral intuitions are driven by the *same factors* across cultures, or (ii) whether the *content* of moral intuitions (e.g. ‘switching in the Loop case is wrong’) is the same across cultures. If I have understood correctly, this study lends further support to the claim that that moral judgements are sensitive to intention and means-vs.-side-effects across cultures. In other words, this study supports the claim that (i) is robust across cultures. This is supported by the finding that participants across cultures morally differentiate between Switch, Loop, and Push in the same direction.

What was different across cultures here was the general level of endorsement for action in any given case. This seems to me to fall under (ii) – the content of intuitions about any given case. Some cultures are more likely to think Loop is morally wrong, for instance, despite the finding that factors like intention play a similar role in their moral judgments. We need to know more about the mechanism driving this – e.g. the mechanism by which being in a low relational mobility society leads one to be more reluctant to endorse sacrificial options for the ‘greater good’ – but, prima facie, there doesn’t seem to be reason to think it’s being driven by a difference of type (i) – that moral intuitions are driven by different types of factors. For instance, as the authors point out, choosing sacrificial options has *different consequences* in different societies in terms of social costs for the agent. So this could (pending further investigation into this mechanism!) be an interesting instance of the way that different types of action have different consequences in different societies, and sensitivity to consequences (including negative social consequences for the agent themselves) has an effect on moral intuitions across societies. This, again, would support Josh’s claim that the factors driving moral intuitions are basically surprisingly robust across societies, while supporting the claim Edouard might be making that the content of particular intuitions is different across societies.

I’d be very interested to know if I’m mistaken about how I’m interpreting your views here.

And right on cue, today’s (1/22) Pearls Before Swine weighs in:

https://www.gocomics.com/pearlsbeforeswine

Click on the comic to open it completely.

I think its important to contextualise the study with this remark made by the authors:

“We relied on voluntary participation in a viral online experiment, and our sample shows clear signs of self-selection…We estimate that a third of our participants were young, college-educated men. Thus, our population is more diverse than a convenience sample of university students, but does not optimally reflect the diversity of the countries we collected data from” and later “75% of survey takers were men, 75% were younger than 32, and 73% were college-educated”

This suggests a couple of things worth discussing. First, it seems likely that this self-selection skewed the proportion taking action. For instance, Greene et al. ran a similar experiment with a more balanced gender representation, and found that men were slightly more likely to take action in a similar set of cases (See section 4.2 here: https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/files/mcl/files/greene-solvingtrolleyproblem-16.pdf) . So folks who are interested in this study to give us insight into the norms of folk or common sense morality might want to be a little wary.

Second, this skew might have some effect on their main claims (i.e. 1. the stability of the Switch-Loop-Footbridge ordering across cultures, and 2. the relational mobility hypothesis). For instance, if the proportion of males (or young, or educated) taking the survey was even more skewed in low-relational-mobility societies, then the correlation they report might start to disappear.

Of course, I’m just being speculative here. And I don’t have the facility with the statistics to really dive into this. But since the data is open, it would be interesting to see someone run an analysis that looked at the effect of gender and education on these reported correlations. A nice little task for a senior project or PhD student!

In my 2016 book, Rightness as Fairness: A Moral and Political Theory, I argue that morality is fundamentally a matter of individuals and groups socially negotiating the costs people should face in pursuing ideals of coercion-minimization and mutual-assistance, and for resolving conflicts between these ideals. I also argue on pp. 181, 191-3 that this means that the trolley problem cannot be settled by rational argumentation (as many journal articles seem to presuppose), but instead must be morally addressed by actual social negotiation laying down social moral norms that individuals (in a relevant context) then justifiably take to be normatively binding. Costs of conformity to moral norms are in turn relevant on my account insofar as I argue that morality is continuous with and derived from prudence rather than a matter of responsiveness to supposedly non-prudential ‘moral reasons’. (https://www.marcusarvan.net/my-book)

These empirical results–which indicate that individuals’ moral judgments and motivation in trolley cases do in fact depend upon perceived personal/prudential costs in relation to different sociocultural norms (viz. risk of alienating others and social punishment)–seem to me to cohere very well with this account, which I further develop as a unified theory of prudence, morality, and justice and defend from existing critiques in a new book coming out with Routledge next month: https://www.marcusarvan.net/neurofunctional-prudence-and-morali

Four in five people would pull the switch?! I think that philosophers can take away from this some evidence that people are very bad at thought-experiments. I doubt if many of them would actually grab hold of such a lever in the real world, deliberately killing that individual.

The connection between loyalty and not pulling the switch, in the minds of those who take the latter to be some evidence for the former, is similarly illogical. Perhaps there are consequences for political philosophy. When we think about how resources should be allocated, are we similarly divorced from our own actual beliefs?

The respondents were asked which option should be chosen, not which option they would choose. (More specifically, they were asked what an agent in that position should do.) A respondent might think that diverting the trolley is what should be done without believing they would actually do it.

Thanks Justin, I had not bothered to notice that detail, which does make a big difference to my observation. Perhaps this shows that people who volunteer opinions on this sort of scenario do not realize that they are saying that agents should commit murder whenever they feel that it would be justified. The fact that fewer say that they should when it is about pushing someone off a bridge, rather than pulling a switch, does indicate that some of them did not notice that detail in the case of the switch. I wonder how many did notice in the case of pushing someone off a bridge. So, there is a similar consequence for the philosophy of politics.

Perhaps that explains the connection with loyalty, incidentally. If someone thinks that an agent should commit murder whenever it seems justified, then what else that is against the law will that person think is OK? A person may well not commit murder, just think that an agent should, but why would a person not cheat and lie and steal to get what they think they should have?

Incidentally, it is quite possible that a lot of the respondents were reporting what they believed they would do, if they found themselves in a similar scenario; we do not know that they were not making this mistake themselves. My own case shows that some of them do!

I won’t speculate about the extent to which this phenomenon was at work in these results, but here’s a study by Dana Nelkin and her colleagues arguing that participants in trolley thought-experiments tend to reject the stated estimates of what will happen if they make certain choices — e.g. not believing that the five people would certainly be saved, or would certainly die, if they made one choice or the other. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cogs.12598

Here’s the abstract (it is a really cool paper):

There is a vast literature that seeks to uncover features underlying moral judgment by eliciting reactions to hypothetical scenarios such as trolley problems. These thought experiments assume that participants accept the outcomes stipulated in the scenarios. Across seven studies (N = 968), we demonstrate that intuition overrides stipulated outcomes even when participants are explicitly told that an action will result in a particular outcome. Participants instead substitute their own estimates of the probability of outcomes for stipulated outcomes, and these probability estimates in turn influence moral judgments. Our findings demonstrate that intuitive likelihoods are one critical factor in moral judgment, one that is not suspended even in moral dilemmas that explicitly stipulate outcomes. Features thought to underlie moral reasoning, such as intention, may operate, in part, by affecting the intuitive likelihood of outcomes, and, problematically, moral differences between scenarios may be confounded with non‐moral intuitive probabilities.

I think that this aspect is crucial to my own answer to this problem, John (and therefore I guess that it is important 🙂

I think that no agent should commit the murder, but should instead spend all the remaining time checking to see if there is something else that can be done. That is to ignore the fact that we are told that there is nothing to be done, the deaths are inevitable. But it is very hard to imagine that fictional fact in a situation where one does have a choice about action.

Also, and more mundanely: while actually I share Martin Cooke’s intuition, I’m not sure his or my intuitions about what other people would do in a bizarre situation are more reliable than their testimony about what they think they would do in that situation.

The answer is that we know more about many of them than they do. Some evidence is how badly most people vote, and how much we intellectuals aim to think realistically about that. We make the effort, and have above average intelligence to start with. It is good that you are not sure, but the whole point of philosophy is that we can know ourselves better by pursuing it.

In this particular case, the bizarreness of the situation actually makes this akin to the famous four card puzzle. In that puzzle, our brains are wired for a quick and accurate intuition about the social version, but even those who get the logical version right have to work it out like it was a math problem. People who are good at math have knowledge by acquaintance with both of those ways of solving that puzzle. They know the difference. And analytic philosophers know about this puzzle and have thought about what it means.

In the switch version of this puzzle, we naturally feel that the puzzle is akin to allocating resources. In the footbridge version, it feels more like murder, but we naturally tend to use our intuitions, and our intuitions about allocating resources may well be leaking into the footbridge version. That is just how we humans are.

Not many people actually think that murder would be justified by the fact that lives would in fact be saved by it. Most people do think that murder is simply wrong. But most people do not work that correct answer out logically. They tend to let the intuitions that naturally arise tell them the incorrect answer. They do not know enough about themselves as humans to catch themselves doing that. We should.

Here’s something I haven’t understood about this sort of “intuition cataloguing”: why isn’t the response just that nothing normative hangs on it, that the “is” of people’s intuitions doesn’t gain purchase on the underlying “ought” question (cf., Hume, Moore, etc.)? In other words, even though we’re trying to track people’s normative intuitions in particular cases, the incidence of those normative attitudes is actually a descriptive fact about the world–not a normative one at all. I know there’s all sorts of methodological stuff in this regard (more critically from Williamson, more charitably from Weinberg) and so on, but grateful for any quick thoughts from the authors or others. Thanks!

Hi Jon: this is a really big issue, but I argue that different meta-ethical and normative ethical theories have descriptive implications for moral psychology, and that we should evaluate philosophical theories in light of all of their implications, both normative and descriptive. As some have remarked elsewhere, it can seem hard to square these kinds of results with (say) mind-independent moral realism. Conversely, I argue that my own preferred approach to meta- and normative ethics predict why people do and *should* take into account personal prudential costs in moral judgment, as well as why moral judgments do and *should* differ substantially across cultures where different prudential costs present themselves to individuals and groups–both of which are things this study found.

Agree that intuitions have no normative force for ethics…but they do for law and policy, which aren’t always aligned with ethics, even if they ought to be.

The reality is that law/policy that demands things that most people don’t want to do (regardless of how ethical that is) is going to be very problematic; and compromise is often needed, if we’re looking ahead at practical implications.

Also, this work on moral intuitions is still valuable in identifying the tensions and distance between ethics and law/policy here, if you want to move the needle closer to ethics, e.g., designing educational campaigns and policy arguments.

Maybe 2020 will be the year that we will read the original trolley problem again and see that Philippa Foot was just showing a problem deontological theories run into that was not seen before. The trolley-problem is that these deontological theories could not make a decision and face a dilemma. Maybe then we will stop this trolley-problem-madness that tries to confuse ethics with hypothetical decision-making of who gets to die in what cruel way.

So because Foot originally used the Trolley scenario for one purpose, no one can ever use it for any other purpose?

“Maybe then we will stop this trolley-problem-madness that tries to confuse ethics with hypothetical decision-making of who gets to die in what cruel way” – there are many completely equivalent dilemmas in military, medical, engineering and humanitarian situations.

That much of academic Ethics is currently sitting on a side track-?

Takeaway1: Ethics is about more than the greatest good for the greatest number.

Takeaway2: Rarely, if ever, can ALL the consequences of an action be determined in advance.