That’s Not Kant

Some people are concerned about Immanuel Kant’s image.

No, I’m not talking about his racism.

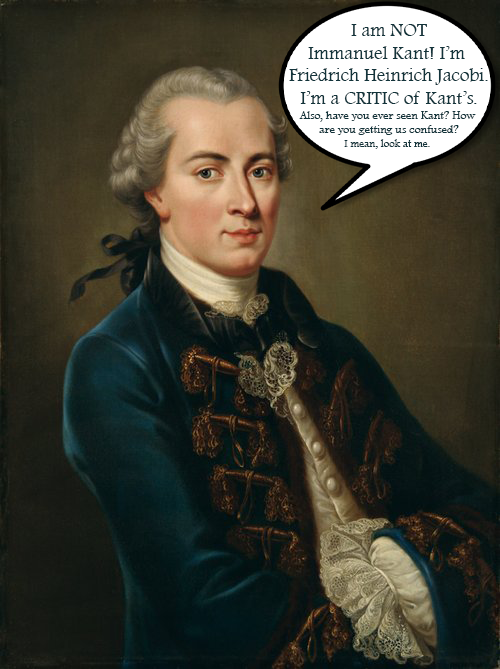

I’m talking about his actual image, or likeness—for the following image, widely used to depict Kant, is not an image of Kant:

Not Immanuel Kant. Seriously. This is a portrait of Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (by Johann Christian von Mannlich)

That’s Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi.

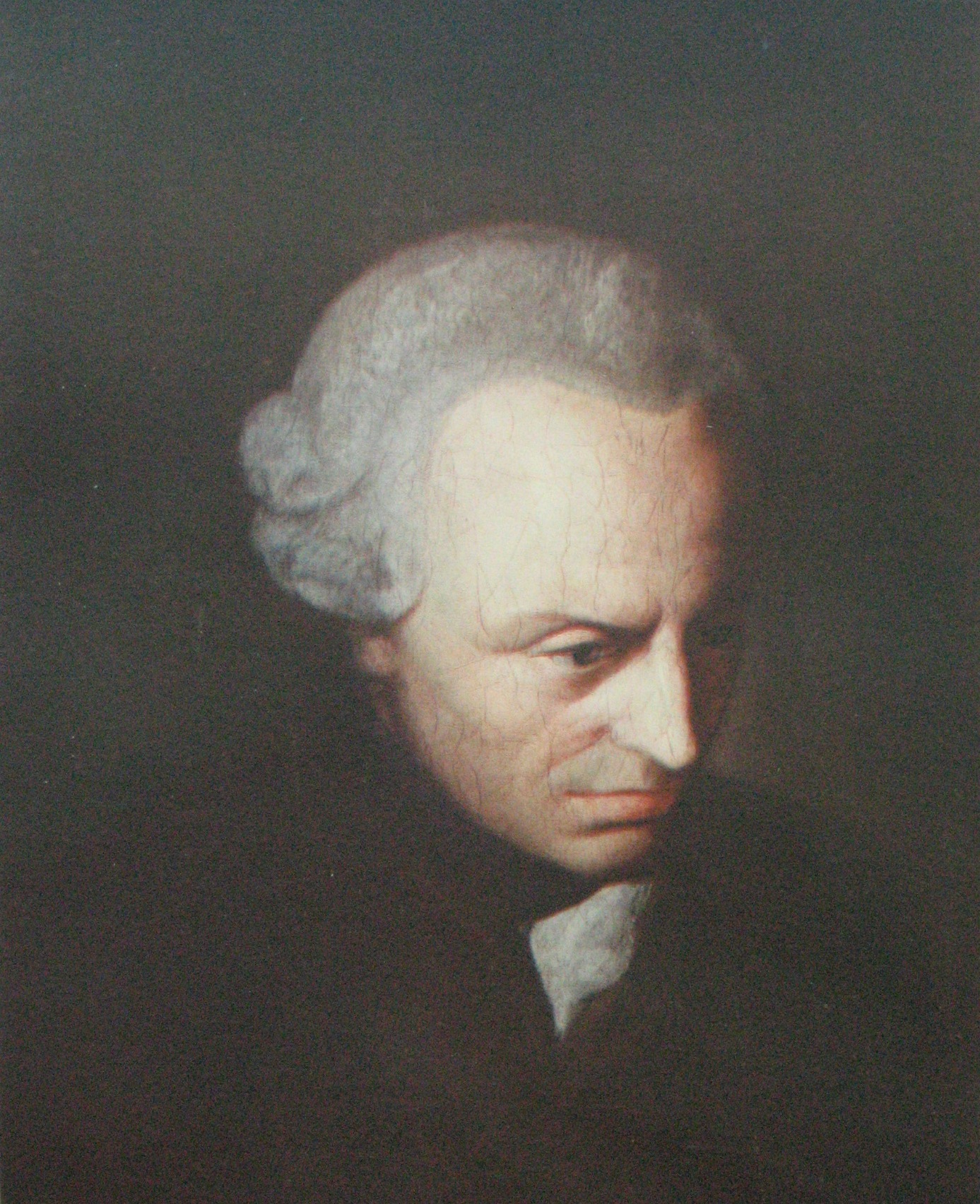

This is Kant:

Okay here’s a better portrait:

Also Immanuel Kant (by a student of Anton Graff, possibly Elisabeth von Stägemann)

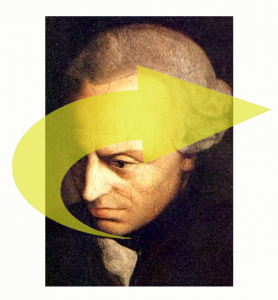

Thanks to Daniele Procida for pointing this out, and for also bringing to my attention a collection of Kant portraits from which I pulled the following badass snake-framed one:]

[Stipple engraving of Kant by John Chapman, 1812]

And here Kant is, as illustrated by my daughter:

Clinton Peter Verdonschot, a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Essex*, wrote to me about the confusion. He says:

I believe it may have to do with the English Wikipedia article on Kant. Back in January 2017, someone changed one of the actual depictions of Kant, the one functioning as the main image, to one of Jacobi because it was “more formal (and better quality)”. Sadly, this person did not check whether s/he changed it to an actual image of Kant. As you might imagine, a minor edit war ensued in which contributors kept (re-)changing the image of Kant for Jacobi and vice versa. The whole thing seems to have been settled on 28 May of the same year, when one editor managed to convince the rest that the painting was actually Jacobi. The actual painting, currently in the collection of the Goethe Museum in Frankfurt/Main, is unequivocally described by the collection’s digital archive as being of Jacobi.

By this time, however, the damage was done. From then on, I keep seeing Jacobi’s image in places where one should find Kant’s. The first time I noticed it was when a staff member at my university used it in his lecture slides on Kant’s epistemology. I also noticed the mistake on a poster for an academic event on Kant’s philosophy, hosted by a research group on German Idealism. And of course, the portrait made its way onto various blogs, the odd pop-philosophical media outlet, and so on.

At first, I found this mildly amusing: we teach our students that it is a cardinal sin to get their information by simply Googling unchecked, possibly untrustworthy sources on the internet (exemplary, in this respect, Wikipedia), and we say this precisely because of the danger of misrepresentation. Evidently, we don’t hold ourselves to the same standards when it comes to a literal (mis-)representation of a philosopher. By now, however, it is no longer amusing: of the first twenty pictures that an Ecosia image search on “Immanuel Kant” yields, seven of them are this damn portrait of Jacobi. It even comes up as the first result, which links, ironically enough, back to the Wikimedia Commons page of the portrait (which, to its credit, at least correctly states that it is a portrait of Jacobi often mistaken for one of Kant).

This has got to stop. I genuinely worry that we might come to erase Kant’s likeness and replace it with Jacobi’s. I do not know why people keep singling out this particular image, though I suspect it has to do with the fact that the portrait of Jacobi is much more handsome than any of Kant’s (as was the reason why it was originally switched on Wikipedia). As philosophers, we are concerned first and foremost with abstract thoughts and not the heads they occur in, that’s fine. It’s only natural then, that we don’t apply such rigorous standards to researching the images we use, we just select the prettiest one. Natural, maybe, but that does not make it right. I would find this business insulting if I were Kant, and I can only imagine what Jacobi, a staunch critic of Kant’s philosophy, would have felt about his likeness being mistaken for Kant’s.

So next time you see a portrait of Jacobi being used to represent Kant, you can just forward this post to the person making that mistake.

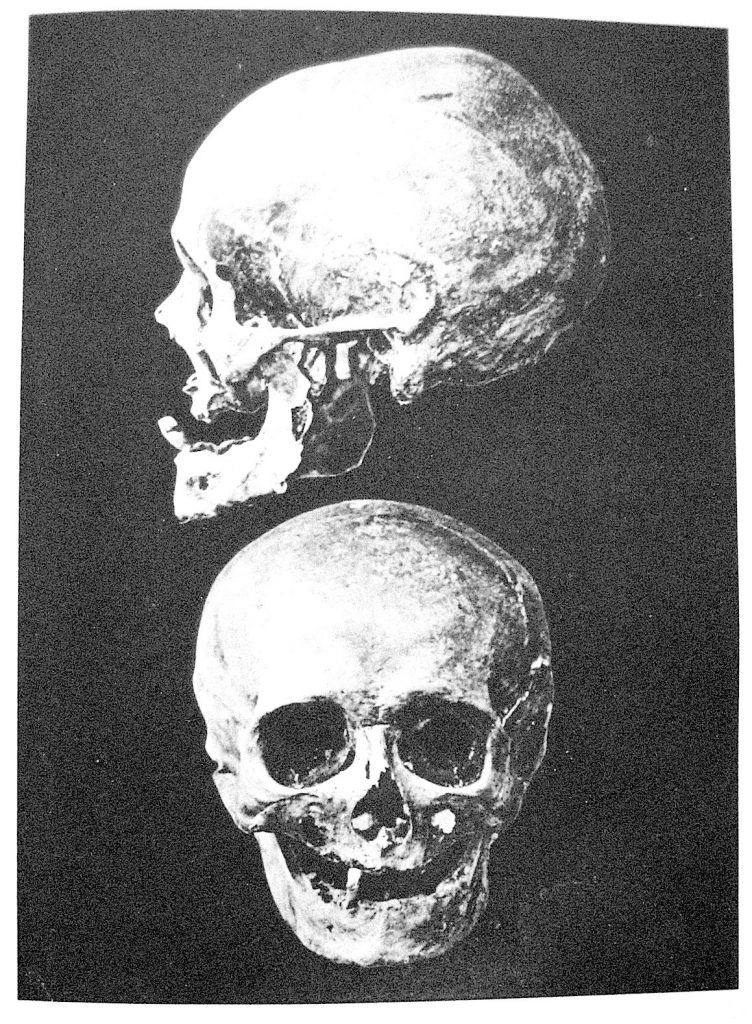

By the way, the following are thought to be the only photographs taken of Kant. Unfortunately they are just of his skull, and were taken after Kant’s body was exhumed in 1880:

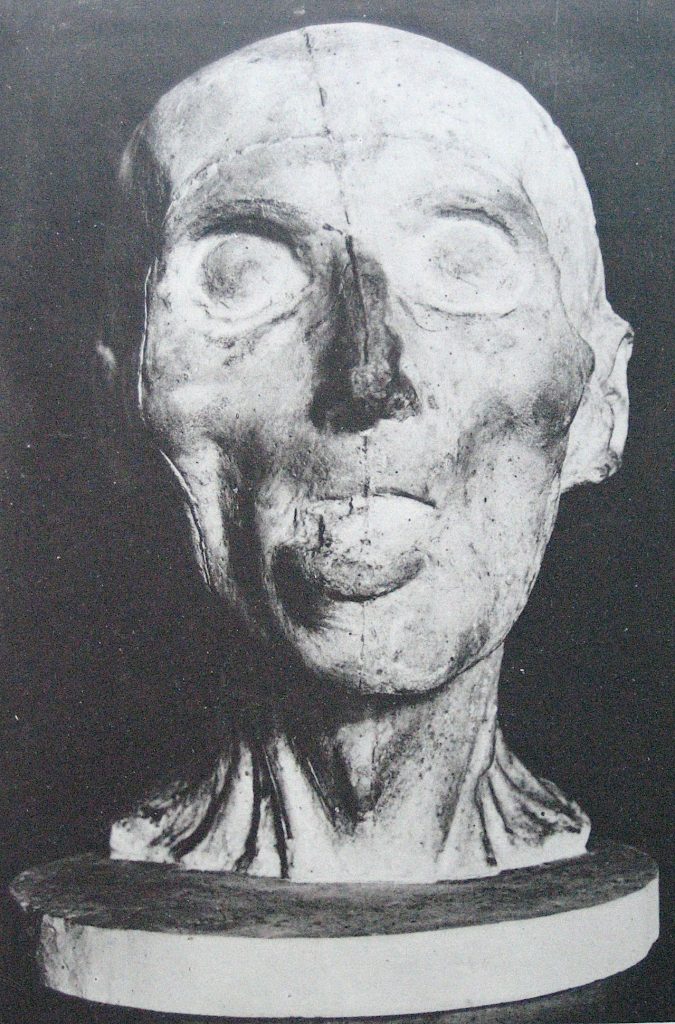

There are even plaster casts of Kant’s head, made shortly after he died by artist Andreas Knorre. Here’s a picture of one of them:

The photos of the skull and plaster cast of Kant’s head come from the remarkable online collection, “Kant’s Body In Pictures,” compiled by Steve Naragon, professor of philosophy at the University of Manchester.

(*The previous version of this post misidentified Mr. Verdonschot’s school.)

UPDATE (10/7/2020):

Many thanks for posting this Justin! Also thanks for the photos of Kant’s skull, fascinating! One tiny remark: I am doing my PhD at Essex, not Sussex 😉

Essex, Sussex, Kant, Jacobi — how can people be expected to keep these things straight?

(Thanks for letting me know. I made the correction. Sorry about that.)

Is Kant suffering as a result of this misidentification?

You know that doesn’t matter!

At least they’re not using the Kant lookalike mentioned in this post: http://dailynous.com/2014/09/19/philosopher-celebrity-lookalikes/

Same thing happens recurrently with Steinbeck and his friend Ed Ricketts (https://www.ecosia.org/images?q=ed+ricketts) and I think the overlapping reason is that Ed was handsomer than John.

I think there’s interesting psychology to uncover there: the tacit assumption or desire that a beautiful mind would go with a beautiful face or some such.

Russell Shorto, in his book Descartes’s Bones, provides a fascinating discussion of some of the historical controversies about Descartes’s appearance — from the famous Frans Hals portrait to alleged copies of Descartes’s skull.

Steven Jay Gould wrote about a phenomenon in science illustration such that the first pictures (usually drawings) that got into texts were reproduced almost without question as accurate, when, in fact, they were not. He cites Duhrer’s drawing of a rhino with armor plating and other misrepresentations that, nonetheless, became the standard for European depictions of rhinos for decades. the unquestioned acceptance of what has been accepted, even if in error, he says occurs in most fields of science and especially in anatomy, biology, anthropology and such.

I think this is what has happened with drawings of Kant and others, not just philosophers. The “experts” say that first painting was Kant, hence it became a portrait of Kant. This is unfortunate but does no real harm, whereas Gould points out that incorrect anatomical drawings might harm actual patients of doctors and so forth, also inaccurate drawings of toxic plants….hmm…

If you would like to see one (of two remaining) casts of Kant’s face, then come to University of Tartu, we have it on display.

Sometime I have the impression that people of that time had all the same face.

I now want to do a book on Kant just so I can use the plaster cast photo on the cover.

The autoicon doesn’t look so bad now, does it?

I could swear this was an issue well before 2017, no? Maybe I’m wrong, but I seem to remember reading about the image of Jacobi being used on bootleg copies of Kant books.

I don’t think the portrait resembles real Kant

Every great philosopher has a grumpy face, not such a pleasant face

In the ‘badass’ portrait: not a simple snake — an ouroboros 🙂