Compensate Graduate Students for Service Work (guest post by Carolina Flores et al)

The following is a guest post* by Carolina Flores (Rutgers), Milana Kostic (UCSD), Angela Sun (Michigan), Elise Woodard (Michigan), and Jingyi Wu (UC Irvine), graduate students in philosophy who comprise the organizing team of Minorities and Philosophy (MAP).

Compensate Graduate Students for Service Work

by Carolina Flores (primary author), and (in alphabetical order) Milana Kostic, Angela Sun, Elise Woodard, and Jingyi Wu

(This post introduces and summarizes Minorities and Philosophy’s report on Service Work Distribution and Compensation Among Graduate Students, which you can read here.)

What do Minorities and Philosophy activities, departmental climate initiatives, undergraduate mentoring, conference organizing, outreach activities like the Ethics Bowl, and prospective graduate student visits have in common?

One answer is that they all rely crucially on graduate student labor, particularly the labor of members of marginalized groups, like women and people of color. In addition, all these activities matter deeply to the profession. They play an essential role in building and sustaining community at the departmental level and creating opportunities for vibrant philosophical discourse, turn departments into more supportive spaces, and contribute to making philosophy a more diverse discipline.

There has been substantial discussions of how faculty who are members of marginalized groups are burdened with a disproportionate amount of service work (in the form of both official roles in the department and of informal support of departmental life and the well-being of its members).[1] Such work—which is central to a department’s functioning—makes it more difficult to carve out time for research. This is almost universally recognized to be unjust and in need of correction. But there has been little discussion of how unfair distribution of service work affects graduate students. Graduate student service work tends to remain invisible, just part of the fabric of day-to-day departmental life.

To bring this to light, MAP (Minorities and Philosophy) used our network of chapters to conduct a study of graduate student service work. Our findings indicate that service work distribution at the graduate student level prefigures the lopsided distribution we find at the faculty level. If departments care about ensuring that graduate students from marginalized groups have a chance to thrive in graduate school and beyond, they must take action to ensure fair distribution and compensation of this work.

We also propose some concrete policies that departments can institute to do better. We encourage faculty to take these seriously, and graduate students to advocate for these in their departments (perhaps with graduate student unions as allies).

That said, these are preliminary proposals. We are keenly interested in hearing from faculty and graduate students about other ideas for improving on the status quo on service work distribution and compensation. We hope this report serves as a springboard for designing, discussing, and eventually implementing fairer distribution and compensation models.

Graduate Student Service Work: The State of Play

Using the network of MAP chapter representatives, we collected information on the distribution and compensation of service work among graduate students in 40 departments, most of which are in the US. You can read the full report here.

The results are only indicative, their central limitation being that they do not rely on official departmental information but just on the perspectives of MAP-involved graduate students in each department (who are mostly members of under-represented groups in philosophy). This might skew responses towards the conclusion that graduate students from those groups are over-burdened. That said, the results are strikingly robust in showing unequal distribution of service work, with special burdens placed upon students who are members of marginalized groups in the profession, and lack of compensation for, or recognition of, this work. They cannot plausibly be discounted by appealing to biases in responses. That said, we welcome further studies of this issue to get a clearer sense of service work distribution.

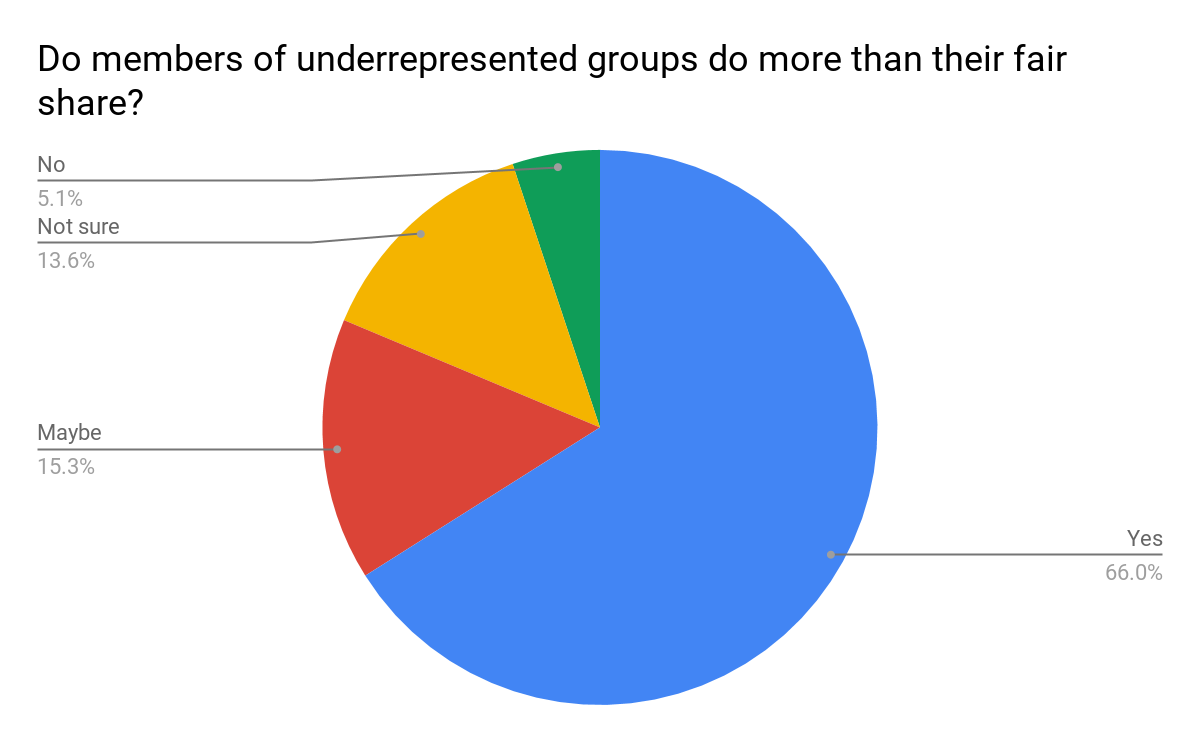

We want to highlight two results. First, service work appears to be distributed in very unequal ways, with members of underrepresented groups shouldering a large proportion of this work (figures 1 and 2). For instance, close to half of survey participants say that less than 15% of graduate students do the majority of the work. In addition, 66% said that this burden was more likely to fall on underrepresented groups, with only 5% saying that underrepresented groups do not do more than their fair share.

Figure 1. Summary of answers to “Is service work distributed evenly? If not, what percentage of people do most of the work?”

Figure 2. Summary of answers to “Do members of underrepresented groups do more than their fair share?

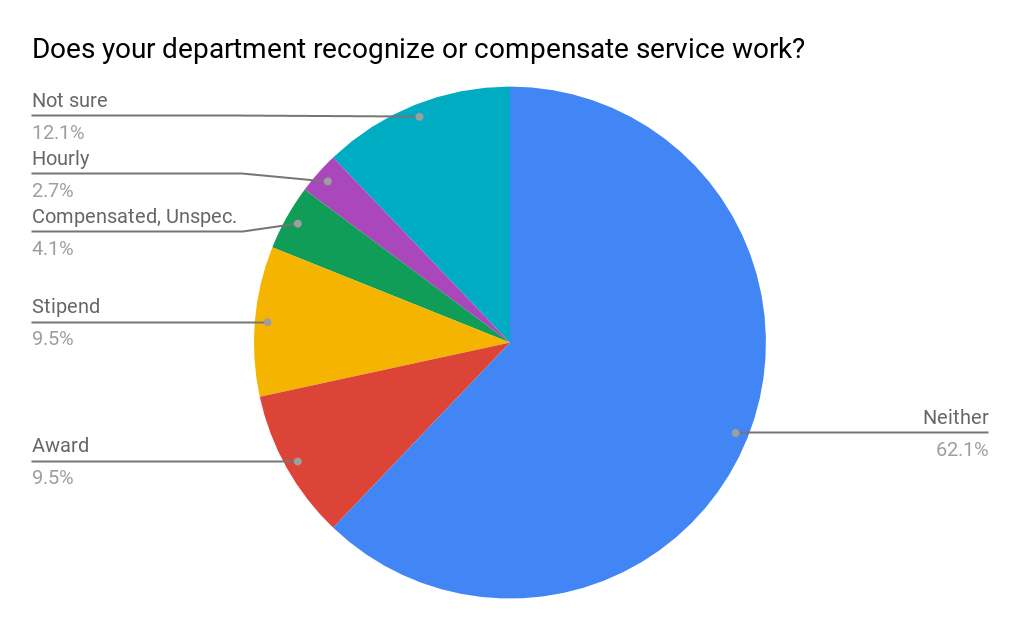

Second, for the most part, departments don’t financially compensate graduate students for service work:

Write-in responses also indicate that departments are more likely to compensate work related to the prospective visit and to organizing conferences. Work that is more community-oriented or more focused on issues of diversity and inclusion is less likely to be compensated.

If you are interested in the details, you can read the full report here. The central take-away is that members of underrepresented groups bear much of the service work load, and are not getting compensated for this. This work takes time away from research and teaching and is often draining, especially when it includes advocating for change in the department, attempting to shift cultural norms, or emotionally supporting others. Further, having one’s important community-oriented work remain unrecognized and unappreciated—though others reap benefits from it—compounds the sense of alienation and invisibility often experienced by members of marginalized groups in academic settings.

Why can’t grad students just say no to service work?

The main response we currently see to unjust distribution of service work is advice targeted at members of marginalized groups to just say ‘no’ to service work.[2] We think this advice is misguided and won’t solve the problems we are concerned about.

First, service work strongly benefits departments and the profession at large. As such, it needs to be appropriately valued, not treated as a toxic waste of time. Second, in many cases, people from marginalized groups are under disproportionate external pressure to take up service work, especially if they have taken up these roles in the past.[3] Third, students from underrepresented groups tend to be particularly attuned to the importance of this service work. This often leads to a sense of moral duty to do service work, especially when it connects to diversity and inclusion. In addition, empirical research on gendered and racialized labor suggest that students from marginalized groups are more likely to have internalized that part of their role in life is to support others and attend to the needs of the community.[4]

To get the benefits of a lively, supportive, inclusive community, without exploiting already marginalized graduate students, departments need to take steps to improve policies around service work. In our view, the central focus here should be on appropriately recognizing, compensating, and distributing service work.[5] To this effect, we have put together a list of suggested policies.

Policies MAP recommends

The following are proposals which MAP recommends that departments take up. Some of these are policies that only faculty can implement; others can be achieved within the graduate student community. We encourage readers to comment with additional suggestions.

Structural policies:

- Financially compensate (at least) especially onerous service tasks, in the form of stipends, awards, or a reduction in teaching or research assistant duties.[6]

- Institute clear standards for what different roles demand and accountability mechanisms to ensure that people do their fair share when it comes to shared roles.

- Limit volunteer-based allocation of service work: instead, make a clear list of available roles and rules for how many roles each student must and can take up over the year and over their time in graduate school.

- Institute simple rules for distribution: e.g. every student must take up one role per year, and none can take up more than three.

- If grad students decide on role assignment at a meeting, then encourage people to sign up for roles before and shortly after the meeting. This limits the amount of pressure on people who attend the meeting.

- Incorporate discussion of the importance of service work in beginning-of-the-year orientation sessions, and publicly set clear expectations for all graduate students.

- Be clear about the value of service work in hiring processes.

Individual behavior:

- Publicly acknowledge and appreciate service work, e.g. through public or personal “thank you”s from faculty for service work. Graduate students should also try to show appreciation for others’ community-oriented work.

- Faculty should be mindful of primarily asking members of marginalized groups to take up service roles (especially ones that do not bring professional advantages), and should always check how many service roles students are already performing before asking them to take up new roles.

- All should avoid expressing special expectations that members of marginalized groups take up service roles.

- All should discuss service work distribution and compensation with prospective students, as a significant factor affecting graduate school experience.

- Members of privileged groups should seek out service work roles.

- Volunteers for shared roles ought to make every effort to do their fair share rather than allow the work to fall on one or two people.

We thank Alex Guerrero, Yarran Hominh, Cameron Domenico Kirk-Giannini, Meena Krishnamurthy, Lisa Miracchi, Keyvan Shafiei, and Justin Weinberg for insightful comments on this material.

[1] See, for example, “Faculty Service Loads and Gender: Are Women Taking Care of the Academic Family?,” “The Ivory Ceiling of Service Work,” and “The Burden of Invisible Work in Academia: Social Inequalities and Time Use in Five University Departments.”

[2] See, for example, “Women, Stop Volunteering for Office Housework!” and “Women of Color Get Asked to Do More “Office Housework.” Here’s How They Can Say No.”

[3] See, for example, “For Women and Minorities to Get Ahead, Managers Must Assign Work Fairly”

[4] “Women, Stop Volunteering for Office Housework!,” for example, suggests that women are more likely to be asked to take up service work and are more likely to accept service work.

[5] Our view is also consistent with some recommendations by empirical researchers. See, for example, “For Women and Minorities to Get Ahead, Managers Must Assign Work Fairly.”

[6] This recommendation (and the remaining) should be read in conjunction with the other recommendations that we put forth, especially the structural ones. Furthermore, we do not recommend depriving minority students of service work that might benefit them. Instead, we recommend that in cases where the service work brings little professional advantage and is inadequately compensated, faculty members should be mindful of primarily asking minority students to perform these tasks.

Thanks for all the valuable work you’re doing!

I’m wondering if there could be further clarification of what the authors mean by “strikingly robust,” and why the results “cannot plausibly be discounted by appealing to biases in responses.” I’m open to this conclusion, but I’m wondering why the authors think this is true. Everyone has biases that can skew results in extreme ways, and when you select only from a certain group, and come out with results that indicate that group has been disadvantaged, I wonder why we should give any credence to the results. If I surveyed subscribers to a libertarian philosophy blog and ask them whether their views are unfairly punished in departments more generally, I won’t be surprised by a overwhelming yes, and I also wouldn’t rely on those results very much.

The study design also seems somewhat skewed– asking “Do members of underrepresented groups do more than their fair share?” seems to prime a particular answer, no?

Thanks so much for doing this work and making these helpful suggestions. I would also add that departments should, wherever possible, *ensure that the service obligations they ask grad students to take on not involve financial burdens* for those graduate students (even “temporary” ones). When I was in graduate school, I was one of three grad members on our department’s colloquium committee: the graduate students were typically responsible for picking up visiting speakers from the airport and taking them to lunch (or finding another grad student to do so) before their talk. Consistent with the data suggesting that a minority of people actually do the work, this task regularly fell to me, as some people were unreliable and others just said they were unavailable. There was no “petty cash” or departmental credit card for us to use to take care of this responsibility; we were expected to use our own credit card and then seek reimbursement for the meal (no one ever mentioned that I might also seek gas money for the trip to and from the airport and I did not think to ask). The university finance office regularly took 4-6 weeks to issue reimbursement checks. After several experiences like this, I complained to a faculty member about what seemed to me an unfair financial burden. I was told, essentially, to suck it up: we were given generous stipends compared to other universities, eating lunch with visiting speakers was an honor I should be grateful for, and “we all have credit cards.” At that point I did not feel that pointing out the interest I was accruing on behalf of the department would be well received.

To top it off, years later I heard through the grapevine that the conversation in which I complained about the financial burden was recounted to a hiring department trying to decide between me and another student from my program, as evidence that I was perhaps not committed to the profession. I am not angry about this–I am tenured now at another institution and am happy where I am. But the expectation that graduate students not only do work for the department, but take on financial burdens for it too (without complaint!) still strikes me as unconscionable.

Sorry to (yet again) be the voice of skepticism here, but I’m really struggling to see what this survey actually tells us. Now, I’m already of the opinion that this phenomenon is probably real, especially since every department has rules/norms about including women and minorities on every committee, and since in my experience women are asked for help (and say yes to such requests) more often than men. But, you know, I’d love to see direct data from our field, so a responsible study would have been nice. But then I read:

“Total number of respondents: 61

Number of universities we gathered information on: 40 (plus 7 responses from unknown departments)

Target participants were graduate students in Philosophy with some involvement in diversity and inclusion work. 92% of respondents identified as members of

underrepresented groups in philosophy.”

To be blunt, I don’t understand how anyone thinks this is data. If a methodology like this were employed in favor of a more traditionally conservative viewpoint, I’m quite sure the authors would dismiss that study out of hand, as would the author of this blog. Even if we assume that subjective impressions of 1.3(!) grads per department are tracking the truth about the entire department, how is this a representative sample of graduate students? Moreover, every group in every organization since forever thinks it does the lion’s share of the real work. Workers think bosses are lazy, bosses think workers are slacking and comparatively unskilled. Would we poll CEOs (1-2 of them out of a workforce of 50) to ask who is responsible for the good-functioning of their company? Of course not. Even if the idea is to deploy some kind of standpoint epistemology, with 1.3 grads per department out of dozens of graduate students, a huge number of voices and impressions are being systematically filtered out, including lots and lots of underrepresented voices. Am I missing something here?

From what I can tell from this post there were three questions on the survey: (1) Is service work distributed evenly? (2) Do members of underrepresented groups do more than their fair share? (3) Does your department compensate for service work? The fact that most of the respondents are involved in diversity and inclusion work and identify as members of underrepresented group might affect their responses to (2) in the ways you describe, but less so their responses (1) and not at all their responses to (3).

It would directly affect (1), because the degree of unevenness will be at least directly proportional to the degree of disproportion among underrepresented groups. Although it is possible they might think work is distributed unevenly and it is the well-represented who are taking on a disproportionate amount, that claim would be implausible and the students polled would have strong biases against considering it. So really, we should expect that (2) is directly proportional to (1), and that is just about what the study shows.

I’m not saying that this survey is of super high quality (because, you know, they are done by unpaid grad students), but:

1. It might as well be true that had a similar survey result be used to support a more implausible conclusion, most people will choose to disregard the study. If you have a very low prior in a hypothesis, then maybe even a very good study won’t be able to raise the posterior above the level of acceptance. In that case, maybe it makes more sense to question the validity.

Of course, since the current survey is not top-quality, the authors shouldn’t use it as definitive proof and should also include supporting evidence from elsewhere, which is exactly what the authors did.

2. If the sample was representative, the claim would be that the proportions represented in the answers are actual proportions of all grad students. No such claim is made (as far as I can tell). As some suggested, the sample might as well be a group of “minority students who care a lot about these issues and like to fill out online surveys”. If most of these people believe that minority students (themselves or others) are unfairly exploited, does that change any of the authors’ conclusions?

Thanks very much for your valuable work on these issues! One question:

What do you mean when you state that people should “be clear about the value of service work in hiring processes”? I think having conducted service work *should* have be regarded as valuable during hiring processes… but I’m not convinced that it currently is regarded as such. In fact, part of what is psychologically taxing about service work is (1) being unsure about whether service work will be of any professional value down the line, (2) knowing that research certainly is , (3) knowing that spending time doing service work might negatively impact your research (at least by taking some of the time that could be spent doing research), and (4) knowing that there are people not doing service work whose research might end up being more impressive in the job market.

When I was a graduate student at Yale, and particularly when I was the elected graduate student representative, this was a major issue. I just want to share some concrete steps we took to try to alleviate some of these problems. I want to list these examples just to provide some ideas for other departments facing these issues:

1. Increase the daily rate at which the department pays graduate students to host prospective graduate students.

2. Have the department be fully responsible for constructing prospective student schedules. Previously some of this fell on graduate student volunteers. Although we raised the possibility of compensating graduate students for this service, the department chose instead to give more responsibility to the administrative staff.

3. Casual department-wide events sometimes relied on graduate students to bring in a baked good and clean up afterwards. For these events, we got the department to switch to a catering company which would also clean up afterwards.

4. Keeping shared spaces clean was a responsibility which often fell to women in the department. We re-organized our elected positions to give two students the power to delegate cleaning duties across the graduate student body, and made sure at most one was a woman.

Thanks everyone for their comments so far! For now, we want to briefly respond to the worry about skepticism about the results. We are very much aware of the limitations of the data, and as we note in our full report, we sincerely welcome improvement upon it. (MAP, as an organization comprised of 4-5 graduate students, does not have the institutional or financial means to run such a survey.) At the very least, our survey data shows that there is a deep need for more research on this topic to see precisely how robust these patterns are.

That said, we see very little reason to think that the survey data—preliminary as it may be—is not tracking a real problem; the only question is how extreme it is. We suspect that more data would not show that the problem is nonexistent but rather that it is more or less extreme than our data suggests. The first type of evidence in support of this is testimonial. One of the most frequently reported problems in end-of-semester surveys, sent to over 130 chapters, pertains to the distribution of service work. According to these chapter members, only a handful of students do the majority of service work within their departments. Second, we have directly heard concerns about the distribution of service work directly in various settings – conferences, workshops, various departments, and the like. The second type of evidence comes from an analogy and inference to the best explanation. The problem of service work falling disproportionately on underrepresented groups is, we are told, well-documented at the faculty level. There is no reason to think that similar dynamics do not hold at the graduate level. (It would be odd if work were equally distributed at the graduate level yet suddenly an unfair distribution was produced once one transitioned to faculty.) Rather, it is more plausible that the problem at the graduate level feeds into the problem at the faculty level. They are two instances of the same general problem, arguably with a common cause.

Finally, some have raised concerns that the data is biased partly because we mainly surveyed current MAP organizers. First, it is not obvious that their participation in service work makes them less accurate. It’s also possible that it might make them more accurate. Compare, for instance, the fact that men overestimate how much housework they do, yet women accurately assess it.[1] Second, even if it is biased, as we noted, it would only show that the problem is less extreme than we suggest, not that it is non-existent. We should already have had high priors that service work is not equally distributed. Lastly, as others have noted, even if our claims about distribution are inaccurate, it would not show that service work ought not be better compensated and recognized.

We look forward to further discussion, and hope to see some discussion of ways to correct the various problems raised here!

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/12/upshot/men-do-more-at-home-but-not-as-much-as-they-think-they-do.html?fbclid=IwAR3TDK1ihDtyJSfnDXkk96yT8GXSrfG6vueF-YNYu_OIKOKHsEsK5UNi7Oc

MAP, thanks for replying to some of these concerns. But I did want to note something very important:

“First, it is not obvious that their participation in service work makes them less accurate. It’s also possible that it might make them more accurate. Compare, for instance, the fact that men overestimate how much housework they do, yet women accurately assess it.[1]”

The reason this fact is reasonably well-established is because they went beyond merely polling women (or, indeed men) as to their subjective impressions of this question. As your linked article shows, various studies in this area have employed in-home observation, collecting data from daily diaries, etc, as a way of *independently* measuring the phenomenon under study. That’s why we are allowed to conclude that women are epistemic superiors in that case. I hope the point is clear. And I’d like to stress again that the problem is worse than this, because even *if* we accept that grads from underrepresented groups are epistemic superiors here, you didn’t survey a representative sample of underrepresented grads. You surveyed people who were guaranteed to skew towards the result you wanted. Frankly, since you had other options for independent checking (i.e. looking at CVs, asking departments for lists of committee members), the skepticism in these comments is perfectly warranted.

Some very different things are being lumped together here.

Some of the items, like organizing (politically neutral) conferences, mentorship (when allocated to students regardless of demographics), and planning departmental colloquia should count as non-partisan service.

Other items, like running MAP chapters and departmental climate initiatives (where the latter refer intentionally or extentionally to pushing a progressivist, identitarian agenda) do not at all seem to be neutral. For a department to explicitly support those while not supporting items that emanate from alternative political agendas would be partisan and inappropriate.

There are, e.g., different explanations for the low relative representation of minorities in philosophy. Some of these hypothesize explicit or implicit racism. Others interpret that representation as stemming from the free, and sometimes, very reasonable, decisions of minority students as autonomous agents, having nothing to do with bias against them. The second of these interpretations, if any, seems more likely to many of us, though the evidence in support of it is seldom mentioned and the (usually nonexistent) evidence in favor of the first hypothesis is seldom contested. And this can be attributed to the stigma of dissent. But even if we treat the matter as an open question, it’s odd to treat the furthering of a partisan view on one interpretation as ‘service’, and the other as non-service.

Those who hypothesize that racism or bias is the cause will see MAP and other initiatives as social progress. Those who hypothesis that free choices are the cause will not. Suppose some other group wished to distribute literature and posters arguing that the MAP literature and posters are fallacious. Should that other group also receive departmental support? Is this not also service? If not, why is the first thing service?

Skeptic: are you for real? Are you aware of the scandals in our discipline over the previous decade?

“Skeptic: are you for real?”

And if “yes”, do you claim to know this by inference or by performance?

I wrote a response to this, but it was administratively deleted.

Lulu, Here’s a different reply to you than the one that got deleted for some reason: do you have in mind any examples of recent ‘scandals’ that involved minority students (or faculty) being kept our of philosophy? If so, please remind/inform us.

So, pervasive sexual harassment , being given differential evaluations on letters of reference, being discriminated against in teaching evaluations, and regularly taken for a student or administrative staff person you are faculty by other faculty does not constitute “keeping people out”? This is all well documented. It’s not 1999 anymore.

The evidence for “pervasive” sexual harassment has never been presented (there have been a few scattered accusations, some more credible than others, usually leading to the ruin of the accused person). The ‘differential evaluations’ thing is at least contested. Being regularly taken for a student or administrative staff person: do you have a citation for a credible study on that? Or is it just anecdotal evidence.

But even if you provided all those things, what exactly does it have to do with keeping out MINORITIES? Connect the dots, please.

Nobody is saying it’s still 1999. I don’t even know what you’re talking about. I’m simply asking for support for your claims, rather than free association between some anecdotes about sexual discrimination and the need for departmental support for things like MAP, which deal with other issues.

1. Carolina et al, thanks for doing this important work! I don’t think I agree with every single idea here, but I’m in full support of the general picture (both of what the problem is and how we might start fixing it).

2. The skeptical comments on this post are depressingly out of touch. This is not a knock against MAP doing this survey, but thinking that we need hard data to corroborate the obviously true claims about disproportionate service responsibilities and work is itself a demonstration of part of the problem here, which is that something about both the nature of service work (and how much of it is “soft” service) and the way it is not valued, along with who is actually doing it and what kinds of biases people have against those of us doing it, makes it particularly invisible/unnoticeable to those who are not doing it. The idea that we even need to collect empirical data here, rather than just being like “listen this is a serious problem and it needs to be fixed”, is itself part of the problem. One thing you might want to ask yourself if you are one of the skeptics here is this: if a woman (who you had no particular reason to distrust) told you that she did the majority of childcare and housework in her heterosexual relationship, would you believe her? Or would you tell her that you weren’t sure, you needed to check with her husband to see if she was telling the truth or was biased? I am completely unclear (well, depressingly clear) about why the word of philosophers who are members of underrepresented groups are not being taken at their word here.

I know some people commenting here would bite the bullet and say that they would need to check with the husband. (And some of you probably don’t even see this as biting a bullet!) I don’t have much to say to those people. But for those who might be inclined to trust her, you might want to think about whether protecting your own self-interest is influencing the way you are thinking about this blog post. In the case I just gave, it’s no threat to you one way or the other if the woman is doing more of the housework and childcare; you’re not the husband, so you are free to sympathize with the woman and judge from the outside. Nor do you need to worry about guilt by association. When it comes to the related issue in this blog post, though, you metaphorically speaking are the husband, and it may well be that being in that position is clouding your judgment about how to appropriately respond, since the threat is… you’ll have to start doing your fair share of the work, which probably seems like it threatens your own self-interest.

That seems awfully loaded, junior faculty.

Let’s try it the other way: if those same readers had a man (whom they had no particular reason to distrust) say that he did the majority of childcare and housework in her heterosexual relationship, would they believe him? Or would they tell him that they weren’t sure, they needed to check with his wife to see if he was telling the truth or was biased?

Junior Faculty,

I think it is unfortunate that those of us who are straight white males (I’ll out myself as one– protestant anglo-american too, if you’ll believe it) have perverse and appropriate incentives in the same apparent direction. If I were merely interested in preserving my ‘self-interest’ (although I’m not sure being a free-loader really counts), then I might want to try to hold these sorts of half-baked (was that a micro-aggression?) studies, overweening policy proposals, and moral self-righteousness to hard standards. Then again, being threatened by social classification as the bad guy would chart a clear incentive path for a moral person to find the truth in order to be vindicated or know for sure that his or her penance was just. The really important thing to notice is that it will end up being uncomfortable either way. In fact, given the lack of insulation for some of us in the academic environment, it might even be easier just to roll over. After all, if I just throw my weight behind the movement then I don’t really lose anything, given that asylum seekers are already being granted mercy.

What I’m trying to illustrate here is that there are two possible explanations for the skepticism– (1) the skeptics are holding onto a self-righteous self-image for its own sake and without regard for the others that its possible deceptiveness might hurt; (2) the skeptics, being moral, philosophers, and human, are given epistemic clarity where their crude self-interest stirs them to question the current social justice ideology and find that it is actually overstepping its bounds.

I’m involved with a MAP chapter and do an overwhelming amount of service work in my department – and I find these suggestions paternalistic and neo-liberal. This is not the kind of change I am looking for. Quite the opposite.

-Increasing bureaucracy around service work increases the work-load, and is oftentimes so prohibitive that it ensures less gets done in the end because of the increased checks and balances. (Like what happens with increasing admin at the university level.) It would also be more burdensome for marginalized faculty, who are also already often overwhelmed with service work. I don’t want more oversight.

-Make a clear list of roles? A lot of our service work is done in response to the changing needs of our students and our department. We need flexibility in order to implement handle issues as they arise. Having increased departmental overnight limits our ability to respond to pressing issues.

-Why advocate that all grad students “must” take up service work? Do we actually want all students doing service work? Many of us are far better suited to take on a lot of these roles than others, given our organizational backgrounds, our personal and emotional investments, and our situated knowledges. This seems more likely to create problems than solve them.

-I really wish these kinds of posts would be done by individuals, not MAP. I don’t agree with these, and I find it disappointing that the group I’m associated with is making these suggestions without explicit consultation with the community.

TL;DR: More bureaucracy, more work for marginalized faculty, and enforced distribution of work that we care deeply about to students who are ill-equipped and unmotivated to do that work is not the right take.

Hmmm… the report *is* published under their own name *as* the organizing team of MAP. Like any other organization, MAP’s subsections can produce reports that don’t reflect the view of the whole organization but are commissioned by MAP. Not to be dramatic, but when a congressional subcommittee produces a report with suggestions it does *not* reflect the view of the congress at large, and it’s still a report that comes from the congress.

(And I do disagree with many of their suggestions. But at least they are very transparent about their method and they’ve opened up an interesting discussion).

As issue-laden as the rest of the post is, my big concern is with the section entitled “Policies MAP recommends”.

I think it’s fair to say that the analysis of the survey should be attributed to the individuals. However, they have made recommendations as “MAP”, which is the concerning part of the post. Some of these recommendations would be disastrous if implemented, and I am very concerned that departments might take them seriously *as* “MAP” recommendations rather than the recommendations of a small number of people involved with MAP, and without consultation with the larger MAP community. (They did, however, send all of us MAP organizers an email yesterday asking us to share this around.)

The tag line of this article is “Compensate Graduate Students for Service Work”. Yes, absolutely, graduate students should be compensated for labor. But for “service” work? What kinds? My feeling is that there’s going to be a vast disagreement about what qualifies as service work – and of what qualifies, what we should be paid for. Not having this discussion previous to posting recommendations is bad form, especially since they are calling for departmental interventions.

Requiring students to do service work needs to be reconsidered as a recommendation. Students who have caregiving responsibilities or who are underfunded (or have additional living expenses) and working outside the department would be additionally disadvantaged. Committees, conferences, and whatnot run by grad students with personal investments in issues would suffer. Anyone who has done a group project, organized a conference, co-authored a paper with someone who is totally uninvested knows that this is a bad idea. The recommendation of a limit on involvement also needs to be reconsidered.

TL;DR: Some of these recommendations would harm underrepresented students. Your department benefits from you NOT KNOWING the difference between service work and unpaid labor, so let’s get clear on that before we recommend giving them more power.

Fair enough. I didn’t notice the language around the recommendations.

Our aim in writing a blog post on this topic was to get feedback on these suggestions *before* advocating implementation of any particular norms, so we are very much open to feedback and discussion about alternative proposals. Anyone is very welcome to email us with alternative suggestions, and we are thankful for those flagged so far.

The post says: “The following are proposals which MAP recommends that departments take up.” If this is not the case, it should probably be edited.

I’m a faculty member, female. I avoided service work as a graduate student, but I have noticed at the departments I’ve worked at that female graduate students do a disproportionate amount of the work. From what I can tell, there seem to have been an almost equal number of male and female graduate students helping to run things. But since there are so many fewer female than male graduate students, it means that about 20% of the male graduate students and 80% of the female graduate students have been doing service work.

Of that service work, the lowest status work–which is not necessarily difficult or time consuming but also clearly doesn’t offer a professional boost and might (tragically) even make some faculty members think less of you, unconsciously level, if they see you doing it–was almost exclusively performed by women. For instance, putting food away after colloquia receptions. I can think of two male graduate students in ten years that I’ve seen help out. It was striking enough in both instances that I still remember them.

A lot of the women also serve as graduate student representatives, and unfortunately, even though that’s quite time consuming and difficult, politically and intellectually, I’m not sure it ends up being much of a professional boost either. Things like organizing speaker lunches would be.

The only real advantage I can see of juggling service work while a graduate student is that it gives you a much more realistic picture of what life will be like as a faculty member. After my solipsistic run in graduate school, I was not prepared.

First off, thank you to Carolina and MAP Cosmipolitan for studying these issues and producing this report!

My perspective, as a late stage grad student…

I don’t see this as an issue that fundamentally has anything to do with *grad students* per se, but is, rather, about how we think of service work and its role in “professional” academic philosophy.

I take it that the idea is that there’s some amount of service work that every professional philosopher is “expected” to do (depending on one’s position), and that if one doesn’t do this, one is informally sanctioned, socially, with a mix of shame and, perhaps, lowered chances of successfully advancing one’s career.

Further, I take it that academia, as a profession, works differently from other professions. Most of us are not primarily or centrally motivated out of desire to “pay the bills”, although we all, of course, need to pay the bills! (By that I just mean: I think most philosophers did not choose to work in philosophy because the compensation is good.) And so we’ve settled into a system where our “official” employment/compensation comes from a university or research center, while it is generally understood that we do not “work for” that university. By that I mean: people like me, at least, think of “my work” as conveniently aligning with what my university wants me to do, but, fundamentally, the university isn’t my boss. The university can’t demand that, come what may, that I do so extra service work over and above any responsibilities that I have agreed to in my contract.

And so I come to the conclusion that the underlying problem here has more to do with old collective action problems that arise from a decentralized power structure. I know that people think this is kinda crazy, but there exists a technical solution to this: various formalized reputation systems and/or electronic currencies.

I don’t expect philosophers to adopt that sort of system, and so I don’t know what should be done.

For the time being, it would be cool if individual departments came up with their own novel solutions for collectively deciding who does what service work. The existing system of “asking for volunteers” seem like something that can be easily improved upon!

TL;DR: This is an expression of a deep tension in the very idea of academic “work” and so I don’t know how we can solve this.

I find it interesting that we seem to find it of vital importance to secure the legitimacy of the data. Obviously that is important as a matter of factual knowledge and as fundamental for wide policy proposals (given at least that for contingently situated problems wider than the scope of a single community’s experience, policy proposals address empirical data and not the stuff of anecdote).

HOWEVER! I think that we should be sensitized to the issue of the distribution of labor in our own communities as a matter of personal and even communal morality, regardless of the sex/race/ethnic etc… identities of the people we work with. That is not to say that sex/race/ethnicity/etc… will not play a role in our decisions and thinking, but that these will at least be local matters of moral decision… again, regardless of whether the conclusions of this study turn out to be true.

As has already been suggested, I think both the report’s findings and its recommendations would be more compelling if it used a tighter definition of “Service work”. The online survey defines Service work as “including but not limited to organizing a MAP chapter, organizing Ethics Bowl, organizing conferences, serving as graduate representative, etc.”. The inclusion of the first item on that list is obviously going to skew the results: if we ask MAP-involved graduates whether they and their friends do a disproportionate amount of the work involved in organizing MAP chapters then the outcomes are rather predictable.

It also raises the question as to how the proposed “concrete policies” are meant to apply to a set of activities so diverse as to include doing volunteer work for a political organisation to serving as graduate representative to cleaning up after graduate colloquia. I can well imagine women being disproportionately burdened with post colloquia cleaning duties: of course they shouldn’t be, and Departments should take steps to ensure these are evenly distributed (a roster, perhaps?). Conversely, I don’t see that a Department has any business at all enacting policies that require students to help organize a MAP chapter (or punish those who don’t) or otherwise regulate the level of grad student involvement in MAP-related activities.

This entire thread reminds me of what a sage once said:

“I used to be an altruist, until I discovered there’s really nothing in it for me.”

Those who volunteer are willingly engaged in elective activity for the benefit of others. It’s lovely, and it defines community. True volunteers demand neither recognition nor compensation.

Those who volunteer, and then invoice others for it, shed the guise of communitarian to reveal their actual identity: opportunist.

Bless volunteers always. Thank and honor them. And gently remind them that taking care of and valuing oneself are prerequisites to a sustainable life of voluntary service. “You’re doing way too much here” is often the case. And burnout is a common feature in voluntary effort. It’s not for everyone. The uneven distribution of generosity is what makes its gifts beautiful. Self-interest is no sin. Kindness is a virtue, not a burden.

In reality, true altruism is rare. Rather, most altruists experience genuine, self-generated returns, often via interdependent preferences. What keeps altruists in the game is palpable self-fulfillment, not selflessness. Thank goodness for that. Did you know that some philanthropists actually forgo the tax benefit?

Beware the purported altruist who then complains of unfairness. They were an opportunist all along.

Some GA contracts are awarded yearly. A contract isn’t always a guarantee from one year to the next. As a result, some grad students feel pressured to do the extra work. Moreover, an overwhelming majority of handbooks state that the school reserves the right to terminate the contract at any time for no reason at all. The students are not given any sense of security.

Just as a light echo of what junior faculty said above: I think it is helpful to see this as a testimonial survey. People at 40 universities said this was a problem. I am less inclined to believe that they are lying about this (it would seem bizarre that they were doing so – unless you took a particularly cynical interpretation of a kind of conspiracy driven by purely political motives.) I wouldn’t get distracted by the shape this was packaged in and see it for what it is.

I don’t think anyone thinks that anyone is lying. But if you’ve ever lived with other people, I think you’d concede that it’s not uncommon for several parties in the same household to feel that they’re doing more than their fair share of the housework. At least I’ve gotten in disagreements with my wife about this. The same thing extends to the workplace. It’s just much easier to notice what you yourself are doing than what other people do.

Hold on there. The survey is NOT asking people whether they are doing most of the work. The survey is asking *MAP-affiliated graduate students* to speculate about whether members of proportionally underrepresented groups take on more than their fair share.

There isn’t just one problem with this. There are many problems.

1. This is a group with a clearly predictable bias, and that bias affects the very thing they are being asked about, and it’s easy to predict that the group is likely to overestimate rather than underestimate the problem (if there is a problem).

2. They are NOT being asked to discuss whether THEY are doing more than their fair share. They are being asked to speculate on whether members of underrepresented groups do more than their fair share. The situation is therefore completely unlike one in which someone, speaking from direct personal experience, says that he or she does the lion’s share of the housework in a two-person household.

3. It would be rare for anyone to even have any way of finding out, in the time it takes to fill in the survey, what the correct answer is. What are the chances that the average MAP-involved grad student knows reliably how many hours per week each other member of MAP, or each other grad student, puts in on these service and advocacy projects? How would they have that information? Through hearing firsthand or even secondhand anecdotes, which are then reported as anecdotes about anecdotes when the MAP-associated students fill in the survey? Many of them probably don’t even have that.

This information is pretty well worthless. Even one of these three things, alone, would be problematic.

Sure, I was assuming that most MAP-affiliated graduate students are minorities, and that they’ll be using their own experience to estimate whether minorities are overburdened with service work.

I’ve just Googled, at random a bunch of contact people for the various MAP chapters. I’d estimate that maybe half of them are minorities.

But even if 90% or more were minorities, this has real problems. Suppose I’m a MAP member and a minority. I get a survey question asking me whether minorities do more than their fair share of service work in their departments. Now,

1) As a member of MAP, it seems highly likely that my political biases would make me overestimate rather than underestimate the proportional amount of work done by minorities;

and

2) As a member of MAP, I’m clearly more likely to be a volunteer myself (since this survey only asks people who are involved in an extracurricular program), so reflecting on my own experience will skew the results in that direction;

and

3) Answering the question accurately through reflecting on my own experience will require me to separate out the extent to which the amount of volunteer time I put in is correlated with my minority status or whether it’s correlated with my being a member of a race-based advocacy group, which would plausibly make it less likely for me to consider how different the experience of other, non-political minorities among philosophy grad students would be;

and

4) I belong to a race-based advocacy group, presumably because of an agenda I care about, and it will not be lost on me that the answer I give to this question could further or inhibit that agenda, so I’d be motivated to overestimate it even if I didn’t have beliefs either way;

and

5) On top of all that, I might not even have a good basis for objectively estimating the relative extent of my personal volunteering, which is supposed to be the basis for my making this general assessment.

I really don’t see how the results of this survey item are supposed to be taken as serious data on this issue.

Yeah I agree with all that. I’m not sure why you’re responding (to this and my previous post) as if we’re disagreeing on anything substantial.

But on a side note, upon Googling MAP contacts just now, my estimate is that close to 100% would count as minorities in philosophy.

Awesome post & report! From experience, I can confirm most of the observations borne out by the survey as applied to my own old department. And I agree with all the recommendations. Without meaning to detract from the important suggestions in any way, I’d especially like to underline the call for the easiest and cheapest one: do just try to say “thanks” from time to time –– you’ll be surprised to find how often you’re the first one to do so.

It is really dispiriting to have ones contributions go apparently unseen, and it can be a great relief to find that your work has been at the very least noticed and appreciated. Thanks to the writers for compiling this report and blog post, and for raising this important issue in such a thorough and thoughtful way.

A general lesson to all philosophers who wish to carry out empirical work: please know how to carry out good empirical work if you are going to base substantive claims on that research. If you do not know how to carry out good empirical work (and this survey really has zero value in terms of providing empirically legitimate inferences about the discipline as a whole) then please recognize that limitation and seek help from others with that competence. Otherwise you open yourself, and your cause, to some pretty obvious kinds of critiques.

I shouldn’t have to say this but…I say this as someone who is intersectionally extremely rare in philosophy: a mixed-race immigrant from a non-English speaking country who spent many years living in the US without documents and who grew up living in extreme poverty. My identity shouldn’t lend my points any additional credence but I want to make clear that I’m not here to protect the status quo. But this survey is just bad work. It should not have been conducted and its results shouldn’t be taken to license any policy proposals.

I am disappointed in many of your responses in this comment thread. You are behaving unacceptably toward courageous efforts by colleagues at vulnerable stages in the profession who are literally asking for your help solving an important problem: unpaid department labor.

For those of you who disapprove of the research methods and have social status in our profession: shame on you for using this opportunity to disparage and personally attack the authors. If you don’t like the methods, by all means design your own research instrument to deepen the conversation about the ethics of unpaid labor in philosophy departments. Use your status and privilege to improve our understanding of the issue rather than perpetuate all the stereotypes that make being a minority in philosophy difficult in the first place. Im embarrassed by my profession most days—by it’s blatant sexism, racism, agism, and ableism—but this comment thread is a new a low. Grow up philosophy!

What’s embarrassing is that you can’t post a reasonable critique of a clearly unwarranted inference from badly acquired statistics without someone baselessly calling it “blatant sexism, racism, agism and ableism”. What an ugly smear. We’re philosophers here. We’re supposed to be good at critical thinking, not unfalsifiably imputing base motivations to each other in a flashy manner.

I think in this case tunnel visioned critical thinking is getting in the way of basic decency. Critiquing a bad inference could be an in road to meaningful exchanges and helpful suggestions. Too much of the above discussion does just the opposite, is not constructive, and I think it constitutes a moral failure.

Also I find the blatant sexism etc part of the climate of much of our profession. I did not mean it as a personal smear to anyone. I think that would be inappropriate. I do think we have a professional and a moral duty not to standby the mistreatment of members of our profession, especially vulnerable ones. I am merely calling out a moral failing in this discussion.

We ought to be hard at work solving the various problems of this profession, which could include unfair distribution of unpaid labor. When graduate students come forward to draw our community’s attention to a serious issue, we ought to take it seriously even if we think further research and debate is called for.

Still Embarrassed, you’re begging the question. Some graduate students have drawn our attention to two issues they say are serious and that you say is serious, but it’s not even clear that it’s an issue. Even a member of a MAP chapter has posted in this thread, arguing that the claims and solutions are poorly thought through and don’t even represent the views or wishes of many members of MAP, whom they apparently didn’t consult. Also, as I and others said already, the whole post runs together service work and advocacy work in a problematic way that we would not accept if its political valence were reversed.

I see no good evidence that there’s a serious issue here. That’s because the methodology was hopelessly flawed. In addition to all the serious flaws already mentioned before, the survey question assumes that those who are members of underrepresented groups (which is not the same thing, by far, as being a member of a MAP chapter) can authoritatively estimate the *comparative* amount of service/advocacy work done by members and non-members of those underrepresented groups. But how would they have the basis for that estimation? It assumes not only knowledge of the amount of time they spend working on these things, but an estimation of the amount of work their ethnically under-represented peers and also that everyone else does. That’s all kinds of bad. You can’t fault us for failing to take the ‘serious issue’ seriously when this is the evidence we’re given that there is a serious issue at all. Let’s establish that first. Again: we’re philosophers here. We should be noted for thinking and then acting. I’m not saying we need to wait until we have perfect knowledge or anything like that. I’m saying, and many of us have already shown, that this survey is so pathetically bad that it gives us no useful information whatsoever.

And we *are* taking the post seriously. We’re not dismissing them: we’re looking at the argument and the evidence supporting it, and examining it objectively. That takes time and mental energy. We’ve identified serious flaws that anyone would see in an instant if the post were arguing for the opposite political agenda. We’ve clearly explained what the problems are. At this point, the message from MAP is not even consistent, since on the one hand an apparent MAP representative here is saying that MAP is not really advocating things that the original post says that MAP advocates. You don’t get to say we’re not taking this seriously just because it’s falling apart as we examine it.

Finally, it really harms your case when you accuse people of “blatant sexism” and “blatant racism” when you have no evidence whatsoever that we are sexist or racist. We’re just engaging in critical thinking. Nobody has uttered a racist or sexist slur or said that one sex or race is superior to any other or advocated discrimination. Philosophers qua philosophers should not go around making accusations like that, especially those that can so easily be shown to be baseless. It discredits you and discredits the profession. And these so-called ‘problems of the profession’ have never been established. They really haven’t. I know you might not think any of this needs argumentative support, but it really does.

I think that the division between paid and unpaid labor in academia is almost impossible to estimate. Will helping organize a conference or write a review or letter of recommendation ‘pay off’ or has one already been paid to do it? It depends on what one thinks is an essential part of the job (already paid for) and what one is hoping to gain. Kindness exists but I think that what we do should really reflect what we value and that a better way to frame the entirely justified request for support for MAP if that is what this is might be this: we are doing the hard work of fixing problems with the discipline that should be born by those who have created and sustained the problems (or at least these costs distributed more equitably). Of course, not everyone in philosophy thinks that these are problems to start with (which is part of the reason they persist) and others just do not care enough to change them. Once they have made this case (and thought about what else they can do to receive compensation!), graduate students should do what they want to do understanding that having the opportunity to participate in department governance and other service activities is possibly a right they should be grateful for just as much as it is a responsibility. That said, I really hope that they continue with this hard work and fully support the idea that MAP in particular should revive departmental and disciplary support!