Placement Patterns in the UK Philosophy Job Market

“Who gets to teach at good philosophy departments in the UK?” That’s the question taken up in the following guest post* by Philip Schönegger, a graduate student in the St. Andrews and Stirling Graduate Programme in Philosophy who is working in ethics and experimental philosophy.

Placement Patterns in the UK Philosophy Job Market

by Philip Schönegger

Who gets to teach at good philosophy departments in the UK? In this analysis, I aim to answer this question by looking at Ph.D. origin and first job placement of academics currently employed at a top-15 philosophy department according to the Philosophical Gourmet report (PG). By doing so, I hope to give prospective graduate students another tool to evaluate the strength of philosophy departments.

Methodology and Data

For data collection, I went to the departmental websites of all PG ranked universities in the UK and analysed the faculty profiles on three points: (i) Where have they studied for their Ph.D.? (ii) Where did they land their first job? (iii) Where are they currently working?

(iii) Per definition, all individuals are employed at a PG top-15 university.

(ii) Based on the departmental or personal (hyperlinked) website, first employment was recorded. No differentiation between fellowships, postdoctoral employment, or professorships was made.

(i) Similarly, origin of (first) Ph.D. was recorded.

If any of (i)-(iii) were insufficiently documented, the data point was not recorded. In other words, if it was unclear where a person received their Ph.D. from or where they had their first job, no data about this entry was gathered. In total, 425 full entries of faculty at PG top-15 departments were analysed.

Results

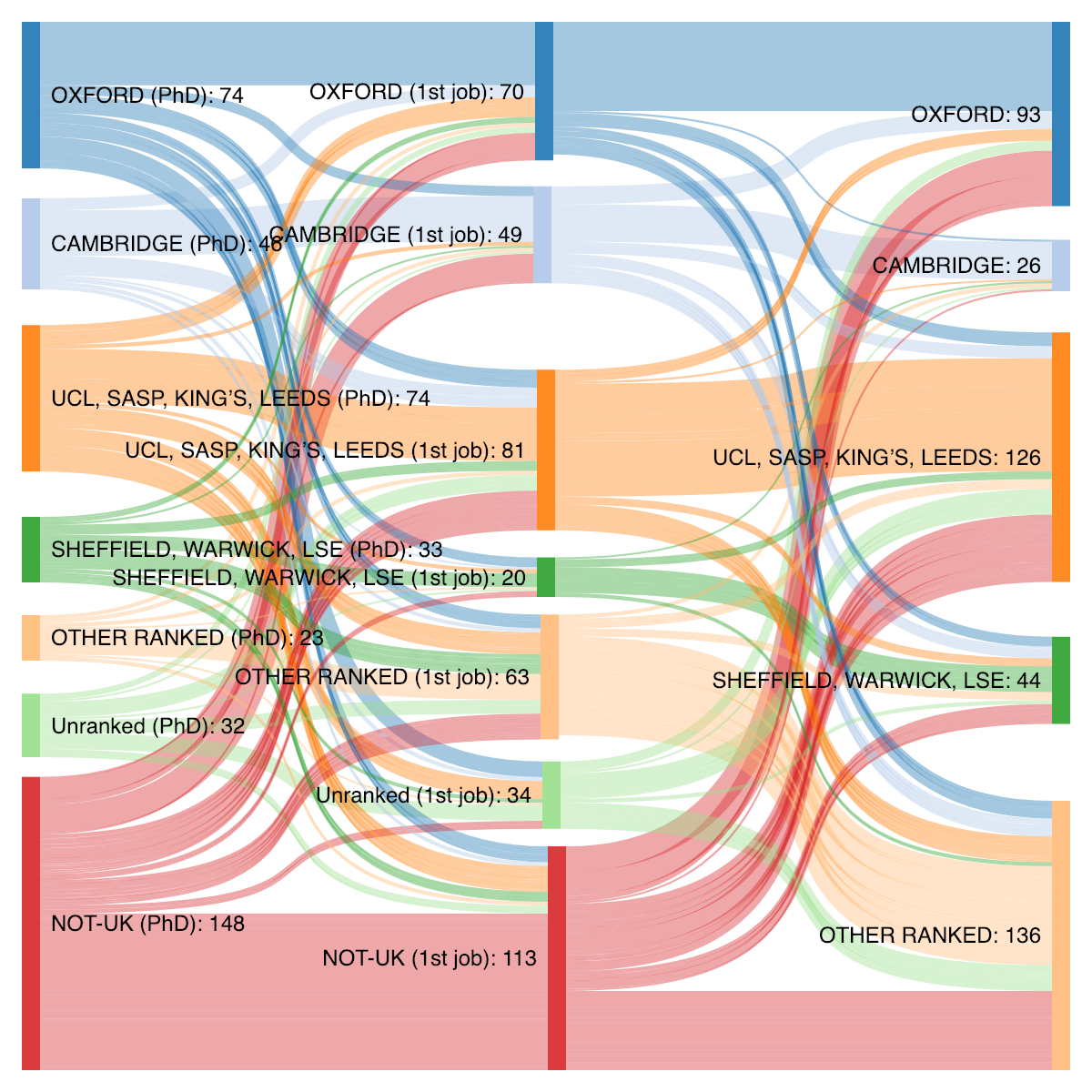

Diagram 1: Left column: origin of Ph.D. (ranked by number of successful graduates); middle column: first job (ranked by number of successful graduates; right column: current employment (ranked by PG report ranking).

148 of the 425 faculty positions at PG ranked departments have received their Ph.D. outside the UK (34%), with the US and the EU supplying the vast majority of those.

Oxford secures placements at ranked schools far and above any other school. Over 17% (74) of faculty have received their doctoral degree from Oxford. About half of graduates also got their first job at Oxford (with a further half of them staying for following jobs or continuing their first employment).

Cambridge graduates secured a total of 46 jobs (10% of all hires), outpacing all other ranked schools except Oxford. Similar to Oxford, a large number of those who get their first job at Cambridge stay.

University College London (UCL), St Andrews / Stirling Joint Programme (SASP), King’s College London, and the University of Leeds are all relevantly similarly successful in placing graduates in PG ranked departments (between 22 and 17). SASP, akin to Oxford and Cambridge, shows a strong relationship between first job at SASP and current employment there. Leeds surpasses all three in keeping the majority of their faculty who were employed for their first job in the department. Together, they account for 17% of all hires.

Trailing the third group, but still relevantly successful in placing graduates are the universities of Sheffield, Warwick, and the London School of Economics (between 14 and 9), together totalling 7% of hires at ranked departments.

Last are the universities of Durham, Manchester, Edinburgh, Bristol, York, and Birmingham who place significantly less graduates at PG ranked departments (between 5 and 3), i.e. just over 5%.

Moreover, only 7% of all faculty positions at PG ranked departments are filled by graduates of the entirety of UK unranked programmes.

Collapsing together these 5 groups, the following picture emerges in which the first three groups are mostly hiring amongst themselves or the non-UK applicant pool. Similarly, the lowest group also hire strongly from their own ranks (and the non-UK applicants).

Diagram 2: Left column: origin of Ph.D. (ranked by number of successful graduates); middle column: first job (ranked by number of successful graduates; right column: current employment (ranked by PG report ranking).

Moreover, diagram 2 shows the strong relationship between first and current job. While this might be due to the fact that some people’s first job is their current one, the data show relatively clearly that if one’s first job is within one group, one’s current job is also very likely going to be in that group.

Limitations

There are a few (potential) problems for the analysis reported here. First, the data presented are subject to a potentially significant time lag. This means that some of the data might go back relatively far, making the results insufficiently responsive to short-term changes in departmental restructurings like hirings. I believe this aspect to be relatively insignificant but due to the data collected I cannot present an analysis to defend this claim (though I might return to this issue with a more detailed data set in the future).

Second, not all departmental websites were equally detailed. Some specified (i)-(ii) for all faculty members, while others did only do so sporadically. For example, the websites for Bristol, Warwick, LSE, and Manchester were generally less specific as to the origin of Ph.D. and the specifics of the first job. However, given that the analysis presented does not specifically differentiate between the PG ranked departments (but rather treats them as aggregates), this limitation might not sufficiently skew the results. As such, not too much weight should be put on the right end of the diagram as this limitation impacts the numbers per department disproportionately. However, given that most Ph.D. graduates do not end up at the same university they received their Ph.D. from, this distorting effect should not be very strong.

Third, the analysis at hand does not differentiate between a person going from a first job at university X to a second job at university Y and then back to university X and a person who stays at university X. Given that the relevant question is what the origin of the Ph.D. is and where the first job was obtained (the left and the middle part of the diagram), this limitation only impacts a small part of the result.

Discussion

I take this analysis to be of supplementary importance when deciding between departments. Given the relative lack of placement data in the UK, these results should be used in addition to other established rankings or primary considerations like departmental fit and supervisor availability.

Five groupings of universities emerge. Oxford and Cambridge, though distinctly different in placement rate (and departmental size) place first and second respectively. A third group of considerably successful departments is comprised of UCL, SASP, King’s, and Leeds. Still relevantly able to place some graduates are departments from the universities of Sheffield, Warwick, and LSE. Trailing all other ranked programmes are the universities of Durham, Manchester, Edinburgh, Bristol, York, and Birmingham.

These results differ in two relevant ways from the PG ranking. On the PG report, Edinburgh is ranked above UCL, though the placement data presented here show that UCL is exceedingly more successful in placing graduates at ranked programmes (22 vs. 4 placements). Second, Sheffield outperforms its rather low PG ranking in these data as well. This suggests that, in general, the data fit with established rankings, except in some cases.

Given the limitations outlined above, the results ought to be taken with a grain of salt. However, as placement data are rare, I understand this analysis to be a valuable addition to one’s decision process nonetheless.

You can follow Philip Schönegger on Twitter here.

There are some serous problems with this analysis. I will mention two. First, it conflates number of PhDs placed with success at placing, although these are obviously different. A department with 100 graduates, 20 of whom get such and such jobs, is less rather than more successful than a department with 15 graduates, all of whom get jobs. It is quite irresponsible to suggest otherwise. Second, the analysis ignores the question of whether graduates who don’t get placed at UK top 15 universities get placed at equal or better non-UK universities, which is crucial if one is trying to under the “success” of a university at placing its students in good jobs. I note this factor is especially relevant because UK universities differ quite a bit in the demographics of their students — some have a lot more Euros, Americans, and other non-Europeans, who it would be natural to expect may be more likely to seek and land good jobs outside of the UK than UK-national students.

Compounding the issue about total placement rate is the assumption here that success should be measured by placement at top ranked universities. Given the apparently abysmal state of the job market a better metric might simply be total placement rate. Sure, almost everyone would prefer a job at a higher ranked university, but the utility difference between no (academic) job and some academic job very likely dwarfs the utility difference between a top ranked job and a lower ranked job (especially once we take into account other, nonacademic, factors that might weigh in favour of a lower ranked university for particular people).

I agree with Toby’s overall point, but I’d like to question his assertion that “almost everyone would prefer a job at a higher ranked university.” Well, many people would, but I don’t think that almost everybody would. I know of a fair number of people who prefer jobs which place less emphasis on research and more emphasis on teaching, even if that sort of job involves a higher teaching load and (in our profession) lower prestige.

Hey Nick,

(i) I agree, proportional analysis would have been better. However, it is nigh impossible to get this data so this is what we can work.

(ii) I set myself the goal to look at who gets a job at PG top 15 universities, see my first sentence, which is why I did not look at any other non-UK placements (and neither did I claim that my analysis held for this bigger picture).

Placementdata.com might be helpful to you. This project works with placement rates (placement divided by total graduates) and includes UK data.

Philipp, I think you are missing the point of my criticisms. Yes, proportional data is hard or impossible to get. But in that case, don’t draw conclusions about which departments are better at placing their students, or which have more success in doing so. In the same vein, yes, you did start off with the goal of looking at who gets a job at PG top 15 universities. If you had stopped there, that would be great, we would learn something interesting. But you didn’t, you went on to make unsupported claims about the placement successes of various programmes, that’s in fact the structure of most of the discussion.

I hadn’t quite registered you were a PG student when I made my first post (it was early!) or I would have been more measured in tone.

That was really interesting, thank you Philip! I would not have guessed that so many at the top 15 had PhDs from the US or the rest of the EU.

I’d be interested to see the top few programs from outside the UK broken out (that is, those with the most PhD graduates currently in UK-Gourmet-top-15 departments). I’d also be personally interested to see the breakdown of the Oceania-trained people, though as there’s 12 I can probably work most of that out in the armchair.

No pressure, of course: the fact that you’ve done a bunch of volunteer work to collect this information doesn’t put you in the hot seat to do more!

Hi Daniel, thanks!

For the US, Rutgers, Berkeley, Princeton, Harvard, and MIT are highly represented.

For the EU, it is mostly universities in Spain (e.g. Barcelona), Italy (e.g. Milan), and the Netherlands.

In Oceania, the majority of graduates come from ANU.

This is interesting. Not so much a comment on the analysis itself, but more on the general issue. It isn’t clear to me that someone who ends up being employed by a non-top-15 UK department loses out much. If we look at the latest report, Birkbeck, Reading, Glasgow and Nottingham are listed as being outside the 15. Is a job at, say, Glasgow clearly a worse outcome than a job at, say, Manchester (or Leeds, for that matter)? As universities, they are roughly comparable. I assume teaching loads will not vary enormously. And there are good philosophers at both departments. Speaking as someone who was until recently looking for a job in the UK, I would have been delighted with both, and would have chosen between them (not that such a choice was very likely!) largely on personal grounds.

I suspect this point generalises. Many (far more than 15) UK philosophy departments (though not all) are housed in prestigious, research-intensive universities, and I suspect that, with the exception of a few places (e.g. Oxford) the job and the opportunities one has don’t differ that much. This represents a pretty big difference with, say, the US, as we don’t really have the category of “teaching schools” that exists there.

Just to be clear: this isn’t so much a criticism of the analysis, as a reason why we should maybe worry a bit less in the UK about “top 15” placement than many in the US seem to worry about “top 50” placement (though even in the US the idea that this serves as a proxy for the question of whether you can hope to get a job in a research university with good colleagues strikes me as somewhat odd).

As someone in a well-regarded UK PhD programme, I strongly recommend that potential PhD applicants look to the US or continental Europe instead. Various political factors are bleeding UK universities dry and PhDs are taking some of the worst of the brunt. PhD funding is bad and often non-existent for non-European students, teaching pay for PhDs borders on exploitative, and staff are overworked and distracted.

I agree with this.

In my experience UK PhD programs have serious failings and are not competitive with US programs (at least not top 50 US programs). The funding is poor. The pay for teaching and grading is exploitative. You get little opportunity to teach or run your own classes. The bureaucracy is just silly and out of control and wastes a ton of your time.

The placement rates of many of these programs outside of Oxford and Cambridge and maybe a few others is difficult to asses and probably low.

The present research illustrates how UK PhDs are not competitive. The US places more PhDs in the UK than Birmingham, York, Bristol, Edinburgh, Manchester, Durham, Warwick, LSA, Sheffield, Leeds, and Kings place combined (1st job).

The degree of cronyism represented in this data is staggering too. I know this exists in the US too though. Sigh…

“The present research illustrates how UK PhDs are not competitive.”

I don’t see that in the data. The UK has 8 PGR-top-50 institutions (Oxford, Cambridge, SASP, Kings, LSE, Leeds, UCL, Edinburgh), and with the exception of Edinburgh all seem to be placing lots of students into top UK programs. Eight out of fifty is about what you’d expect given the UK’s population. It’s true that lower-ranked programs don’t place many students into higher-ranked programs, but that’s true in the US too.

Whether true or not, it misses the point. There’s more to doing a PhD than whether or not you will get an academic job at a top department in the UK. There’s the matter of the quality of life of PhDs and whether or not the need for teaching on a CV and good will towards students is financially exploited by universities and departments for the sake of placing well on UG rankings. And in this way, prospective PhDs would be better off looking elsewhere.

You made several claims; I was only commenting on one of them, that UK PhDs are not competitive with US programs as regards placement. I don’t know enough to comment on your other claims (I know Oxford well, but as you say, it’s anomalous and observations about it probably don’t generalize to the rest of the UK sector).

There are some important differences between US and UK PhD programmes that students should be aware of, which connect to the supposed different levels of success in placement between UK department. The main difference is that US departments have been churning out a lot of students for a long time, for a variety of reasons, including the role that PhD students play in supporting undergraduate teaching. In the UK there were far fewer PhD students, and these were typically only very good students who were able to win national funding, and they did a three year research degree with zero teaching. This is why so many great departments have ‘low placement’, to use the misleading expression in the original post — they simply didn’t produce very many PhDs until very recently, as in the past few years. This is even understating it – there were many departments, even top departments, that had almost no PhD students. That has changed in the very recent past, but goes a very long way toward explaining differentials in the quantity of students placed in UK top 15 departments.

Regarding this comment:

“The present research illustrates how UK PhDs are not competitive. The US places more PhDs in the UK than Birmingham, York, Bristol, Edinburgh, Manchester, Durham, Warwick, LSA, Sheffield, Leeds, and Kings place combined (1st job).”

Is it unsurprising that a country with over 300 million people has placed more people in UK jobs than 11 UK departments combined, some of which didn’t even exist as universities when some current faculty were doing their PhDs? York was founded in 1963, Warwick in 1965, and University of Manchester in 2004! Moreover, several of the other universities mentioned are older (around 1900) but didn’t develop as major research universities until much more recently. That they didn’t produce PhDs in the 1970s, 80s, 90s who could go on to land jobs in UK departments is totally irrelevant to whether they are good places to do PhDs now, and to their placement records in recent years, which is presumably what would matter to prospective students.

I’ll respond by just looking at one University, the U. of Manchester.

Let’s clarify something.first. The U. of Manchester goes back a long way. Before 2004 it was two different universities: UMIST and Victoria. These universities go back to the 1800s. Also these universities have a lengthy record of academic achievement.

From Wikipedia,

‘The University of Manchester is a major centre for research and a member of the Russell Group of leading British research universities.[50] In the 2014 Research Excellence Framework, the university was ranked fifth in the UK in terms of research power and fifteenth for grade point average quality of staff submitted among multi-faculty institutions (seventeenth when including specialist institutions)[51][52] Manchester has the sixth largest research income of any English university (after Oxford, UCL, Cambridge, Imperial and King’s College London),[53] and has been informally referred to as part of a “golden diamond” of research-intensive UK institutions (adding Manchester to the Oxford–Cambridge–London “Golden Triangle”).[54] Manchester has a strong record in terms of securing funding from the three main UK research councils, EPSRC, MRC and BBSRC, being ranked fifth,[55] seventh[56] and first[57] respectively. In addition, the university is one of the richest in the UK in terms of income and interest from endowments: an estimate in 2008 placed it third, surpassed only by Oxford and Cambridge.[58]

Historically, Manchester has been linked with high scientific achievement: the university and its constituent former institutions combined had 25 Nobel laureates among their students and staff, the third largest number of any single university in the United Kingdom (after Oxford and Cambridge) and the ninth largest of any university in Europe.’

So, it’s not like the University of Manchester is some brand new university with little clout or standing. It has a famous past going back far longer than 2004. It’s also highly respectable today. It’s misleading to say that it didn’t exist until 2004.

So, given what we now know, let’s look at their placement according to this data: 4 placements in UK departments. Even if this only includes the last 15 years, after its name change. 4 placements in 15 years? Of course we’d need to know how many PhDs they’ve produced in that time, but I bet it’s quite a few, i.e. 30 or more most likely (2 a year). Looking at their website they have 31 current PhD students. So, they may have produced over a hundred PhDs. 4 placements in the UK? Not looking good folks!

I don’t see that this says anything very specific about UK departments in particular.

That placement number is (AIUI) not total placements, but placements in the UK PGR top 15 (i.e. roughly equivalent to the US PGR top 50, though really it’s more like the top 80 given the relative populations). And Manchester is ranked around the bottom of the PGR’s UK top 15. I wouldn’t expect a US department near the bottom of the top 50 US departments to place many students in top-50 departments, and I wouldn’t expect a UK department near the bottom of the top-15 UK departments to place many students in top-15 departments. That’s just how the (Anglophone) job market works, rightly or wrongly: people normally place in lower-ranked departments than they do their PhD in, just as a matter of arithmetic combined with a reasonably strong department hierarchy.

I didn’t say the University of Manchester was a brand new university with little clout or respectability. If anything the point was the opposite: although it is new as a university, it has tremendous clout, and a ‘study’ that looks at how many people with jobs in top 15 UK universities have PhDs from “The University of Manchester” is what is misleading. Nothing you say changes this.

I have no information about the placement rate of Manchester over the past 15 years (nor does the author of the ‘study’ I was criticising). But I don’t see why 4 placements in top 15 universities is so terrible, especially when you bear in mind that few people land jobs immediately after they defend — especially in the UK, with three year PhD degrees, and automatic tenure which generates risk aversion, making department lean toward hiring people a few years out with more of a track record. Remember that Top 15 in the UK is probably like top 50 in the US, and while placing 4 people in Top 50 departments over 15 years isn’t amazing, it isn’t *that bad* either. Find me a US department that is similar to Manchester in terms of Leiter rank that has that record with US departments. Maybe there are some, that would surprise me.

Where do you see that they have 31 current PhD students? On this page they say they have 15:

https://www.socialsciences.manchester.ac.uk/philosophy/research/postgraduate-research/

Can I make two final points, in case anyone following this thread is genuinely interested in understanding the differences between the UK and the US with regard to PhDs and placement? In my experience there a couple of key differences between the systems.

1. My sense is that it is much more common in the UK (and in Europe generally) to pursue a PhD (in a humanities subject) without wanting an academic job, and indeed while thinking of it as a deliberate step to something else, or just something fun to do while you’re young. I think this is because PhDs are typically only 3 years (and in England undergrad degrees are only 3 years), making it quite easy to be done with a PhD by age 24 or 25 and jump into law or policy work, etc., at an early career stage. It may also be that these sorts of degrees are more valued in the UK, I certainly have the sense that the US is more anti-education/anti-philosophy than the UK, where the liberal arts are booming. I think placement rates — whatever the facts turn out to be, which the OP didn’t provide us with — should be read in that context. Many US departments only want PhD students who will get academic jobs when they finish. In the UK many departments think their role is partly that, and partly to provide high level education to people who will work in policy, govt, industry, etc. (Again, I think this is a euro thing.)

2. In my experience UK philosophy departments, at least the elite universities, have much more diverse PhD-student-bodies than American universities by national origin/country of UG degree. Among other sociological reasons, this is because UK universities are disproportionately prominent within Europe, which has as many people as the US. E.g., in my department there are PhD students from all over the place, at least a dozen countries (some of which are multiply represented), and many apply for and get jobs ‘back home’ after they finish. I know this happens to some degree in the US but it is much less common. Trying to assess the success of UK departments at placement by looking at placement in UK universities is a bit like looking at the success of California or Massachusetts universities by looking at placement in California or Massachusetts. That is exaggerating of course, but the general point holds. (Remember that for centuries UK universities have been educating the elite from other countries and then returning them home, the US is much more about inward traffic that stays. This is just a difference between the countries and their education systems that should be understood.)

The second point is very much worth making. My PhD cohort was very international, and many have TT jobs in their home countries.

Recent discussion concerning whether UK departments are competitive with US departments involves the notion that places like Manchester probably place a lot of people outside the top 15. I have my doubts, and I have some honest questions.

1. How many departments outside of the top 15 are there in the UK that have analytic philosophy departments? I don’t know, but I wouldn’t guess there are more than 15 additional universities in the UK outside of the top 15 that have analytic philosophy departments. I might be widely mistaken, but whenever I search for jobs I don’t see too many universities outside of the top 15 with ads up.

2. Does PGR rank really matter that much in the UK? There is plenty of evidence now that the US is prestige crazed. I always thought because of the REF that the UK was a little more meritocratic. However, that doesn’t seem to be what David Wallace is saying. Is it true that you really shouldn’t aim higher than the rank of your graduate program in the UK when applying for jobs? Is this effectively a waste of time?

Anyway, I think it’s obvious that answers to these questions mean a lot for the present discussion.

(1) There are around ~30 high quality UK philosophy departments, depending on exactly how you count.

(2) This is all just my personal impression, but my experience is that:

(a) The hierarchy in the UK is much flatter than in the US, both in terms of actual quality and in prestige.

(b) Departments care *much* more about the REF than PGR rank, since the former comes with government money, and more importantly feeds into things like league tables in the newspapers, and that in turn affects student intake.

(c) I think David Wallace is way off if he intended to imply that gradutes will struggle to move upwards from the ranking of their PhD instituion: my experience is that departments will hire based *primarily* on publication record, because publications are the primary input into the REF.

(I should add that I’m with Nick that the information above is really not that useful for ranking UK departments.)

I think Alex is completely right on 2a and 2b.

I also think that PhDs in the UK are much more research based and have little to no coursework component. This means that almost all of your ‘training’ comes from your supervisor, meaning the overall quality of the department or university is largely irrelevant to the quality of your thesis and it seems like hiring departments realise that. I.e. if you do your PhD with Professor X at prestigious University Y and then he/she moves to less prestigious University Z, it wouldn’t change your thesis or how you are perceived by hiring departments. Futhermore, since funding is often done on quotas (each department will have x AHRC grants to give), sometimes students will get into a more prestigious and less prestigious department but accept the less prestigious offer because they have funding for him/her. Unlike in the US, you can’t assume that the student attended the highest ranked university they were accepted at.

I agree with the points made here.

1. There are no more than an additional 15 analytic philosophy departments outside of the top 15 in the UK, plus or minus a few.

2. Prestige according to PGR rank doesn’t play a big role in the UK.

If 1 and 2 are both true, then the data we have for top 15 placements should worry us a lot.

We shouldn’t expect placement outside the top 15 to be that much better than within the top 15. Also, we shouldn’t expect placements to occur in that many additional departments.

This is different from the US where we would expect a lower ranked top 50 to perhaps place better outside the top 50 than within the top 50, and where there are probably 100-150 additional universities that have analytic philosophy departments (or combined departments that employ analytic philosophers).

In the US, outside the top 50, there is wayyyyy more than an additional 100-150 departments that hire philosophers.

Maybe but they’d be inconsequential if they only employ 1 philosopher and hire once every 40 years. I’m interested in universities/liberal arts schools/whatever that are substantial employers and worth considering here.

Right, but to A’s point, there are about 5000 colleges and universities in the US. I’m sure a lot of them don’t employ philosophers, but 150 does seem like a very low guess to me.

The APA has about 6300 members. Not all of those are employed as academics, of course, but many employed academic philosophers are not APA members.

It was just a guess.

My conjecture is there are way more notable employers of analytic philosophers in the US outside of PGR ranked schools than in the UK, even taking the countries’ relative populations into account.

I consider this conjecture on my part. I think it is true based on who I see advertising on jobs.ac.uk, and also many of the universities my wife interviewed at in the UK for psychology didn’t have philosophy departments at all.

Quick reply to various comments (DN threading is making it tricky to do so in situ):

– I don’t think I actually made any first-order claim about how the UK job market works – only that *if* the UK job market worked the same as the US one, you’d see the pattern described here, so that pattern isn’t’t evidence for a difference between UK and US hiring opportunities.

– That said, the pattern in the OP tracks the PGR UK ranking really pretty well, which makes me skeptical that departmental reputation is a poor guide to placement success in the UK.

– The fact that UK departments prioritise research doesn’t mean their hiring patterns should be less correlated with departmental rank than in the US (where plenty of departments also prioritise research, it should be said!) That turns on an issue we’ve discussed on DN before: how much institutional reputation correlates with other measures of job-applicant quality, whether due to program selectiveness, quality of mentors, quality of peers, etc.

– Pendaran asks: is it really true that you should not aim higher than the rank of your graduate program when applying for jobs? I wouldn’t give that advice, in the UK or the US. If you think your CV, and in particular your publication record, makes you competitive for a given job, apply for it no matter where you did your PhD. These are statistical generalizations, not iron laws. But just as a matter of arithmetic, if there’s any reasonable correlation between what grad school admissions committees look for and what hiring committees look for, you’d expect to see something like that pattern, because strong departments admit many more PhD students than they hire faculty.

‘That said, the pattern in the OP tracks the PGR UK ranking really pretty well, which makes me skeptical that departmental reputation is a poor guide to placement success in the UK.’

Perhaps a third variable, e.g. department size or number of PhD students, explains the apparent connection?

I find it hard to believe that PGR rank has much to do with employability in the UK for myriad reasons I won’t get into. I think Elizabeth above though outlined some of them quite well. I may be totally wrong though.

Thanks David – just to confirm, I think we are in agreement: there might be some *correlation* between departmental prestige and hiring of their PhDs, but I take it that this is better explained by selection effects etc. rather than by hiring committees actually caring about prestige of PhD-granting institution. From that point of view, PhD students should apply for jobs wherever (as you say) and prospective PhDs should not be driven by prestige-related considerations (though of course, they might take into account the actual quality of a department!).

All that said, I think there is still something misleading in what you say: As Pendaran implies, the ranking in the OP is best explained by relative sizes of departments, not by PGR-rank.

On the correlation: yes, absolutely. (There’s then a further question about what are good metrics of quality, and in particular whether PGR is a good metric; that’s a whole other conversation.)

On the ranking in the OP: I don’t think the numbers add up for that.

(i) Oxford placed 74 students in the PGR-top-15 UK departments; Durham, Manchester, Edinburgh, Bristol, York, and Birmingham collectively placed 23. Oxford’s PhD program admits about 15 students per year; for sheer size to explain the effect then on average those six programs would have to admit fewer than one student per year. I’m fairly certain that’s not the case.

(ii) If it was just size, you’d expect a random distribution of PhD-holders around departments: the average graduate of Birmingham would be as likely to get a job at Oxford as the average graduate of Cambridge, there are just (we’re hypothesizing) more of the latter. As the OP points out, this is clearly not the case: there is a very substantial sorting into bands.

Yes, fair enough, I probably overstated that. Perhaps I should have said that departmental size is playing an important role with some of these numbers, even if other factors are influencing them too. (Oxford, to be fair, is a very big outlier in part because they hire an awful lot of their own students, and there is also a question about whether their *recent* placements are quite so dominant compared to the above data which is partially tracking hires made many decades ago. But again, you’re right that I overstated my point.)

I didn’t notice that Alex also made the point about Oxford. It applies to Cambridge too it seems.

I’d love to see more data looking at the rest of the UK’s big philosophy departments like Nottingham etc.

This is all fascinating!

The data we have seems to suggest many people staying within the ranking tiers they graduate from. This is different from the US where it’s normal to get a job at a department significantly below your PhD granting institution (I did some research a while back and found the average drop to be 14 tiers). Also, Oxford and Cambridge seem to produce a great deal of their own hires, which skews their overall placement. It does seem that something like PGR rank is playing a role in the UK, but the situation isn’t exactly analogous.

I’ve just been playing with the data (the OP was kind enough to share the dataset) and I don’t think it’s true that there’s not downward motion. Here’s a breakdown, among students who got final jobs at UK PGR-top-15 departments, of where that final job was:

– Students with a PhD from Oxford (PGR rank 1):

Rank1: 41% Rank2: 5% Rank 3-6: 22% Rank 7-9: 15% Rank 10-15: 18%

-Students with a PhD from Cambridge (PGR rank 2):

Rank1: 23% Rank2: 15% Rank 3-6: 21% Rank7-10: 13% Rank 10-15: 28%

-Students with PhDs from PGR rank 3-6 departments:

Rank1: 13% Rank2: 0 Rank 3-6: 45% Rank 7-9: 12% Ranks 10-15: 31%

– Students with a PhD from PGR rank 7-9 departments:

Rank1: 9% Rank2: 2% Rank 3-6: 19% Rank 7-10: 33% Rank 10-15: 37%

– Students with a PhD from PGR rank 10-15 departments:

Rank1: 5% Rank2: 0 Rank 3-6: 12% Rank 7-9: 27% Rank 10-15: 56%

33% of Oxford graduates ended up with jobs at departments ranked 7 or lower, as did 41% of Cambridge graduates and 43% of graduates of rank 3-6 programs, so that’s a fairly significant downward flow (while only 30% of graduates of rank 7-9 programs, and 17% of graduates of rank 10-15 programs, got jobs at rank 1-6 programs, and only 11% and 5% respectively got jobs at Oxbridge). You can’t see downward motion directly in lower-ranked programs because the data cuts off at 15, but there’s fairly good evidence of it coming from the fact that the numbers getting jobs at all are so much lower, as we discussed above.

You can also do this the other way around: of the permanent staff at the institution who did PhDs in the UK PGR-top-15, where did they do their PhD?

Oxford faculty:

Rank 1:57% Rank 2:20% Rank 3-6:11% Rank 7-9:7% Rank 10-15:4%

Cambridge faculty:

Rank 1:31% Rank 2:62% Rank 3-6:0 Rank 7-9:8% Rank 10-15: 0

Faculty in rank 3-6 departments:

Rank 1:25% Rank 2:15% Rank 3-6:40% rank 7-9:12% rank 10-15:8%

Faculty in rank 7-9 departments:

Rank 1:22% Rank 2:12% Rank 3-6:12% Rank 7-9: 35% rank 10-15: 20%

Faculty in rank 10-15 departments:

Rank 1:16% Rank 2:15% Rank 3-6:19% Rank 7-9:19% Rank 10-15: 32%

More than 3/4 of Oxford faculty, and more than 90% of Cambridge faculty, who did their PhD in a UK PGR-top-15 department, did it at Oxbridge. But about the same number of such faculty in rank 10-15 departments have Oxbridge PhDs as have PhDs from those departments. Yes, relative size (especially of Oxford) explains some of this, but it’s nothing like large enough to be the main driver.

We’d have to compare this to US data to know for certain, but my sense is that the situation isn’t analogous. As your data shows, many stay within the tiers they graduate from. I suspect this occurs far less in the US. Also, Oxford and Cambridge hire so many of their own graduates that I almost think they are their own special case and muddy the waters.

But I do have to admit that it seems something like the PGR plays a big role in the UK, which is counter to what people have consistently told me. I should have just gone to the best ranked program I got into. I didn’t understand how the system worked at all.

I’d love to see data for all UK departments.

I only skimmed some of the comments but, while I saw various criticisms of the methodology, I didn’t see any making the point I’m about to make.

In the spirit of transparency (and because it’s relevant to the point that I want to make) I’ll begin with my own career history. I have a D.Phil from Oxford, had my first (temporary) job there, then my first permanent job in Stirling (part of SASP), before moving to my current job, which is not in either the top 15 or in fact in Philosophy at all.

Why is this relevant? Well, the question that this is supposed to address was “Who gets to teach at good philosophy departments in the UK?” It’s not clear to me that this is helpfully answered just by looking at who currently teaches in these departments.

Clearly, I did get to teach in two good Philosophy departments. Moreover, had I not chosen to leave Stirling, then I probably still would be doing so. Yet, so far as I can see, this analysis will not include me, nor others like me. That means we may be missing many people who have got to teach in good UK philosophy departments.