Some Philosophers Are Leaving Twitter

Two philosophers with relatively popular Twitter accounts have quit using the social media service in recent days, both citing the mental tolls their engagement with other Twitter users has taken.

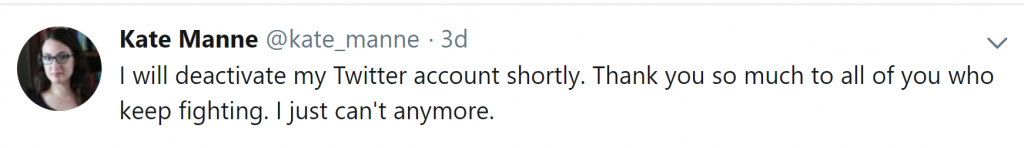

A few days ago, Kate Manne (Cornell), whose tweeting about philosophy, politics, and culture, often on the themes of her book, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny , announced she was deactivating her account:

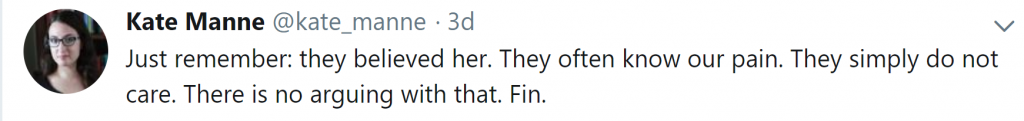

Manne, who regularly and patiently engaged with hostile Twitter users about her work, was receiving additional attention over the past month or so owing to the relevance of her ideas to the nomination and appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. Indeed, one of her last tweets referred to the testimony of Christine Blasey Ford about Kavanaugh’s alleged sexual assault of her:

Manne was the fifth most popular philosopher on Kelly Truelove’s “Philosophers’ Favorite Twitter Feeds” list.

This morning, Brian Earp (Yale, Oxford) announced he was taking a break from his Twitter account:

Folks, I think I’ll step away from twitter for a while. The norms of accepted discourse even among academics seem to allow for a degree of meanspiritedness, mockery, point scoring, snideness, etc it’s taken its toll. I’ve met a lot of really kind people on here. Wish you all well

— Brian D. Earp (@briandavidearp) October 29, 2018

Earp was 35th on the “Philosophers’ Favorite Twitter Feeds” list.

Two departures is not sufficient for a trend of any sort (if you know of similar exits, let me know), but they are a reminder of the challenges of online engagement, both with the public and within philosophy.

Modeling exemplary discourse online can be exhausting and dispiriting. The sheer volume of nonstop communication Twitter facilitates can be overwhelming. It is not always easy to resist provocation from trolls-at-large and members of the profession who seem to enjoy being jerks. Plus, the public is so large, and individual conversations so small, that after a while it is only natural to wonder whether one’s efforts are making any difference at all.

As for what to do about the “meanspiritedness, mockery, point scoring, snideness” and the like that Earp sees academics accepting, I have no solution. However, it might be useful to keep a couple of things in mind as you engage online on Twitter, Facebook, blogs, etc.

First, in almost all of these contexts, you owe no one a reply (or further engagement). So if you decide not to reply to someone because you don’t like their attitude, or you don’t think it would be a good use of time, or whatever, your decision is not in need of justification.

Second, it’s okay to not “win” online debates. Philosophers should already be comfortable with this but for some reason—perhaps because it seems more public—they are less comfortable with it in the context of social media. Remember that “I’ll think about that” is a perfectly fine response.

Third, try not to let what you take to be the bad behavior of others provoke you into engaging in bad behavior yourself. Don’t let the worst people turn you into a worse person. Be better than them, and try to take pleasure in that.

Further suggestions welcome.

Hallelujah! Philosophers are finally coming to their senses and getting off that wretched simulacrum of conversation. Let’s hope it’s a trend.

I’m not so certain it’s a good thing. I’ve found it immensely valuable for networking with other philosophers. I could do without a lot of the “complaining” but insofar as it has allowed me to reach out to other philosophers and learn their current projects, it’s been fun and educating.

People were networking long before there was Twitter. The evidence is pretty overwheming not only that these platforms bring the worst out of people but that they are partly responsible for the alarming rise in anxiety and depression among young people.

Do you have links to some of these studies?

No I don’t. My wife is a high school teacher whose school is wrestling with the problem of cell phones and social media. She and her committee are the ones who have surveyed the research.

I’m sure you can find it easily. The

Connection between social media and depression is a major topic of public conversation right now.

Hi Ken,

You can find discussion of and references to some of the relevant research in this article of mine:

https://quillette.com/2018/04/17/social-media-case-deactivation/

Thanks Jonathan.

Here’s a suggestion: all philosophers (and everyone else) should leave Twitter. It’s terrible, narcissistic, and emblematic of much of the worst of the profession (and us). Put your phone down, read a book, or take a run.

More generally, the rise of social media corresponds to many societal woes, specifically polarization and divisivess. (Insert cite—there’s plenty to pick from.) Aside from echo chambers and confirmation bias, the biggest issue is reducing substantive debates to sound bites, bereft of context, subtlety, or nuance, plus shortening our collective attention spans and encouraging/facilitating trolling.

We’d be better off without it.

Here’s another suggestion: Don’t just leave Twitter (if you have an account) but change your attitude towards it, regarding it as a disreputable platform that reflects badly on the individuals who use it. And (mildly) express this attitude to your friends, family, colleagues, and students so that a social stigma attaches to being active on Twitter.

> Put your phone down, read a book, or take a run.

This kind of attitude strikes me as toxic and elitist. Why are those hobbies better than engaging in social media?

Of course you might say: social media can make one toxic, or mislead you, or so on. But of course so can books, or any other form of media or communication. Twitter is a new evolution in communication, not a brand new phenomenon that we can just pretend never happened.

I think he’s absolutely right. Reduction ad elitist is not an argument.

Neither is your comment, so I’m not sure where we’re left.

Any serious opinion that can be expressed in 140 characters or less is really not worth much, is it? Oh wait, this is less than 140 characters. Never mind.

But seriously, the general tone of twitter seems to lend itself to being snide or worse. From college athletes tweeting purely nasty comments about their opponents and how they are going to annihilate, to the president doing the same, the negatives of being on twitter seem to greatly outweigh the positives. Not to mention the addictive quality it seems to have.

Courteous discourse demands more space and time than 140 characters affords.

Oh dear, times have changed. It’s 280 characters now.

And you can always have a thread…

I rarely feel so hip and on top of technology : ).

I’ve actually found the format of “Twitter thread” to be an interesting new one that seems to have some value. Unlike the traditional essay or blog post, a Twitter thread encourages you to make one self-contained point in every 140 or 280 characters. It’s obviously not the right format for everything, but a writing medium that encourages a particular rhythm of points being made has some virtues that aren’t replaced by other media.

The individual tweet may not be a great medium (at best it can be an aphorism or one-liner) but the tweet-thread really does add something new (even if the problem of how to view it nicely hasn’t really been solved).

I disagree on the basis that Twitter forces concentration, time management, and coordination of information. Many things come to light at a fast pace.

For example, Twitter has helped me focus America’s insidious problem with words. It is a deep symptom of failed education and cognitive disarray.

On The Atlantic now there is a valuable article by J. M. Berger on the Alt Right: A Twitter Taxonomy. Tell me about the characterization of the Proud Boys as “a discreet organization.” Should it be “discrete”?

What is the evidence?

If you are a specialist in discourse you need to be on Twitter. And manage potential addiction.

David Graham

Staff Writer, The Atlantic

—is on the case.

I believe in a conversation people are naturally owed (good) replies. A better reason for ceasing to engage can be that your interlocutor violates certain norms of constructive conversation (e.g., repeated neglect of contrary evidence), or that you have other priorities to attend to, or that their response pragmatically demands no reply, or departs from the focus of the conversation (e.g. ad hominem attack, note that sometimes even strongly emotional responses have some propositional content, and are subject to dispute, and are owed a reply with respect to that). A decision to dismiss based on one’s dislike of her interlocutor’s attitude might disrespect the right to respectful replies.

As a relatively popular philosopher on twitter (10K followers) I think its important to keep two rules in mind:

1) do not get into discussions. twitter is not for discussing. Just write your point of view and only discuss with people who think alike.

2) if someone behaves aggressively with you, just block him now. discussing with haters is a waste of time and energy.

Following these two rules can make the experience in twitter much better. I hope this is useful.

Why would you want to just state your opinion without having a discussion?

Why do people give speeches without Q&A after? They could be after influencing people, informing them, etc. Not everything has to be a one-one discussion.

This probably came out a bit more negative than I intended. But I think Diego is gesturing in the direction of something genuinely unfortunate about Twitter.

It seems like Diego is right that Twitter is unsuitable for engaging with people you disagree with. But it doesn’t sell itself that way. As a result, the only way to enjoy Twitter is to either avoid matters of substance or to avoid dialogue in a medium that sells itself as conducive to dialogue.

The former I have no problem with, and if someone wants to just follow George Takei, that’s great. But to just throw out opinions and not engage with objections reinforces the general feeling that those on your side of the issue have no good response. It also creates an echo chamber for you, by definition. I don’t think either of those effects are healthy epistemically or conducive to healthy epistemic communities.

Never have been able to bring myself to use Twitter. Facebook itself is already way too constraining. But what can anyone say with any serious thought in 140 characters or less? Twitter exists for point scoring and hoisting one’s flag, for signaling, nothing more. Why anyone even bothers with it is beyond me.

Actually, Twitter is extremely valuable if you know how to use it, in the same way that the great COBUILD English Grammar is—only if you know what to do with it, how to teach adverbial subordination, reported clauses, and cohesion.

Twitter is invaluable as linking to a huge corpus of quickly-moving, accessible fresh text from all perspectives, but philosophers have such a constrained view of language. For example, they do not grasp the poverty of the American connection to words.

David Graham at The Atlantic took the responsibility to have the mistaken word “discreet” in the story about the alt-right and Twitter referenced above in Daily Nous comment changed to “discrete.” No philosopher showed any interest in this language problem in so far as I know.

It is wretched behaviour. No wonder students in Harvard College are so disorganized.

The teaching of critical thinking is low grade, partially because of the lack of realism in teaching language and cognitive psychology.

@ClaytonBurnsPhD

So, I just wanted to make a quick and tentative response to the comments here encouraging philosophers to leave Twitter altogether. Quick background: I’m an applicant to graduate programs in philosophy, from a place where I have no direct access to philosophy departments, events, and professionals. I have some limited, mediated access to people at my undergraduate institution, of course, but most of my sense of what the philosophical community is talking about, what people are interested in, and, in general, what people are like, comes from the interwebs. Now, of course I do keep in mind that online personas are different from what people are like in real life, but I’ve found it very valuable, as I plan and prepare for a possible academic future, to have this kind of access to philosophy chatter. I’ve come across a lot of useful links, discussions on current and recent work, open-access resources, information on what kind of talks people are giving, going to, and interested in, and so on via Twitter that I almost certainly would not have had I just been browsing institutional websites and these blog pages. I even manage to get some quick questions in, and often get helpful responses and references in reply, in a way that is not possible on, say, Facebook (since I am neither friends nor “friends” with many philosophers) or email (it’s nerve-wracking enough to email people I *know* to ask about things!).

All that said, I do of course wish both Brian and Professor Manne the best with their Twitter breaks; I’ve seen a bit of the nastiness they’ve had to endure and I don’t blame them at all for wanting to leave. I definitely *understand* the thought that Twitter discourse is terrible if you have a philosophical community around you anyway, and if I were in that position I find it very plausible that I would think that as well. But if Philosophy Twitter at large were to suddenly disappear, I know that I would lose quite a lot of the sense that I might be part of this wider community as well, and I imagine that others like me – I know there are at least a few! – would also lose something. So I just wanted to put that out there for your consideration!

“Modeling exemplary discourse” might also be too boring to be sustainable. I really, really do not want to read anyone’s feed who thinks about it like that.

“Model” rollicking, free-wheeling discourse or go home.

I know I’m in the minority here, but I have found my corner of twitter (philosophy/logic; medieval studies/medievalists; SFF writers focusing on diversity and inclusion; past students) to be an immensely supportive and wonderful place. I have learned so much,– and been able to share so much of my own work–, gotten so much support, and made so many friends. There are at least three people that I’ve met on twitter that I am making plans to try to meet in person when I’m back in the US for Christmas. These are people I am likely to have never otherwise met, but we share interests in beer, logic, and the grammar of dead languages. In my book, that’s definitely a win.

I have so far basically completely managed to have escaped the notice of the trolls — the only trolling/harassing/defamatory comments I’ve ever gotten have come from fellow philosophers, sadly, but they have been minimal compared to all the positive benefits I’ve gotten. Part of this is luck. Part of it is that logic is not generally inflammatory. Part of it is that I happily wield the “block” and “mute” buttons.

I’m surprised to hear someone praising the science fiction and fantasy Twitter community. My strong impression is that since “Racefail 2009” it has been incredibly toxic whenever political issues of any sort become salient.

While I understand that people who’ve been subject to trolling or abusive rhetoric on Twitter may end up with a negative view of it, I have to disagree with some of the dismissals of it (a few of which read as if written by people who have never taken the time to learn how to use it).

I found Twitter overwhelming, confusing, and annoying at first, but once you learn to control the flow and regulate what you pay attention to on it, it can be useful, informative, and fun. I’ve seen on Twitter a good number of interesting philosophical exchanges, cogent and concise arguments advanced over a series of tweets, links to interesting and new (to me) research in philosophy and outside of it, and many good jokes and witticisms.

It can be a rough experience for some—especially on explicitly political subjects. But if you are selective in the people and organizations you choose to follow and interact with, you may get something good out of it.

You can follow Daily Nous on Twitter, and if you go to TruSciPhi you can scroll down to the philosophy section and check out various lists of philosophers and philosophy organizations others follow.

While Twitter has some good things to offer, I’m very concerned about the downsides of its widespread use, by philosophers and by anyone else. My concerns fare based on the research summarized by M. J. Crockett in this article:

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/modern-outrage-is-making-it-harder-to-bettersociety/article38179877/

A couple key points:

“Altogether, this [research] suggests that online news platforms may be artificially inflating people’s experiences of outrage.”

And

“All this social reinforcement may make expressing outrage habitual.”

(For theoretical background, see LaRose, “The Problem of Media Habits,” https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01360.x)

I see the increasing prevalence of habitual outrage as a disaster for our society. Its effects are clearly so thoroughgoing that it would be naive to expect “philosophy Twitter” to escape them. That is, habitual outrage surely affects how its subjects spend our (yes, I include myself in that group) time researching, writing, and teaching. To speculate for the sake of concreteness: will research on the kinds of largely symbolic, wedge issues whose tribal relevance is clearer, and that therefore elicit more outrage, gain at the expense of research into more technical policy issues? Or for that matter, at the expense of positions whose joints aren’t carved by the current constellation of online tribes? I don’t mean to suggest that symbolic/wedge issues don’t matter, but rather that habitual outrage in the service of a tech firm’s profit is likely to nudge us towards pretty imbalanced priorities.

Another clarification: I don’t doubt that some people are able to use Twitter without becoming habitually outraged. The concerns I’ve been raising pertain to larger populations using the platform.

I don’t want to speak for anyone, but I worry that suggesting the mental toll public engagement on social media takes on certain people, among them philosophers, can mostly be chalked up to a general lack of charity and civility or an overwhelming volume of responses obscures a very important piece of the equation. Philosophers like Kate Manne who advocate for social justice and write on topics like misogyny are subject to the most vile, despicable personal attacks and even threats, to rampant misogyny or other prejudice relating to their particular social groups (in Prof. Manne’s case, a staggering amount of antisemitism; homophobia, transphobia or racism for others…) In addition to subject matter, social identity/positioning makes certain people especially vulnerable online. We should be all the more appreciative of the hard and important work some scholars and activists are doing in the name of social justice in light of the great risks and burdens they take on with regards to their physical and emotional safety and mental wellbeing, not to mention the lawsuits feminists like Prof. Manne have been threatened with. I don’t know that I’m objecting to what the OP exactly; it just seems super important not to overlook this dimension of things.