Room for Uncertainty in Online Philosophical Communities

“Uncertainty, I once thought, is what philosophers do. Now I have doubts.”

Those are the words of Amy Olberding, professor of philosophy at the University of Oklahoma and one of the most thoughtful observers of the philosophy profession, in an essay at The Chronicle of Higher Education. (The essay is paywalled but may be accessible through your library’s website.)

The current essay builds on themes she has discussed earlier.

Professor Olberding observes the “pugilistic practices” of philosophers interacting on social media and blogs:

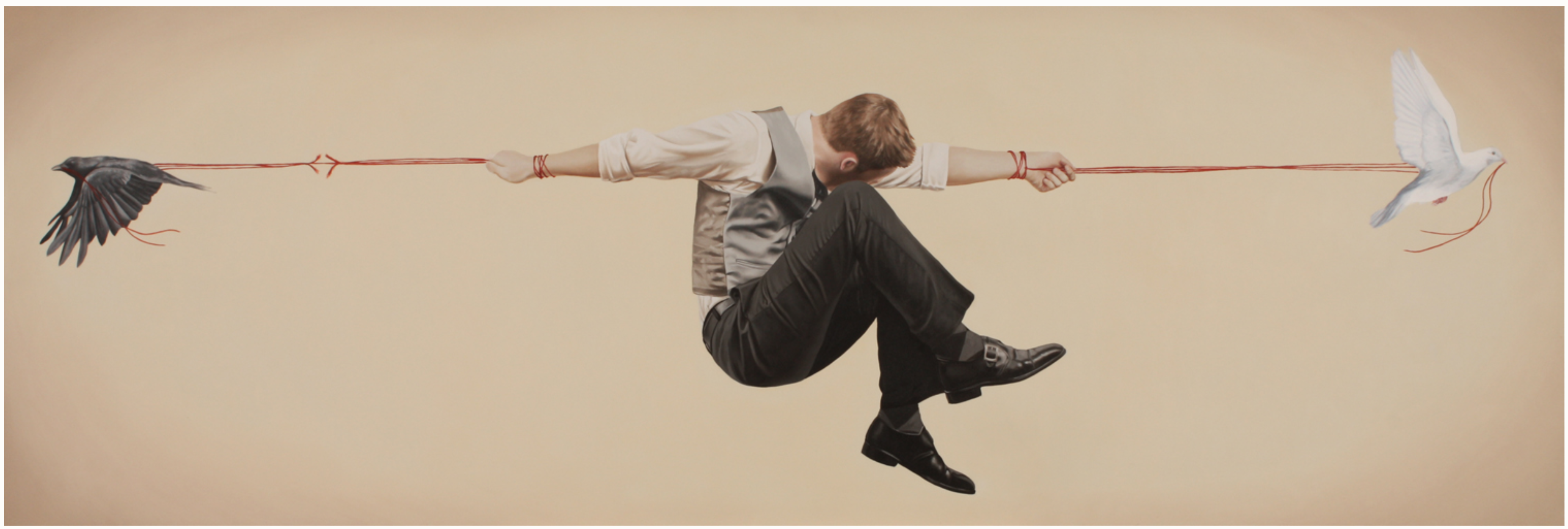

Philosophers of all stripes wield the heavy weaponry of scorn, derision, and insult online. The rhetorical assaults take a couple of general forms: assailing the basic competence and intelligence of one’s opponent or assailing her moral scruples and humanity. Though the rhetoric typically includes lively flourishes, much of it amounts to slinging charges of stupidity or hatred back and forth. And, because this is philosophy, the slinging can go meta: Philosophers will not only rhetorically punch an opponent—when challenged they may justify their punching with elaborate claims that he needed punching and, by the by, if you’re doubting this, maybe you need punching, too. This is where our online conversations are most demoralizing: Certainty of one’s own views transforms into cruelty cast in self-valorizing terms. Cruelty becomes righteous, the cruel heroic.

She notes how the results of these practices run counter to the pursuit of wisdom, with discourse that is limited and, in an important way, unphilosophical:

The casualties of these pugilistic practices are many, but the one I mourn the most is uncertainty. Philosophers who harbor uncertainty are simply unlikely to participate in online dialogue. The fervent antagonism of the interaction selects against those who have no “side,” so we will rarely hear from the importantly perplexed or learn what new complexities they might discern. But more than this, I think the nature of online dialogue distorts and corrupts uncertainty itself, though I struggle to say just how.

I suspect that uncertainty cannot be effectively expressed. Trepidation, doubt, hesitation—these can be leveraged by the insincere as subtle weapons of attack. A posture of “uncertainty” is sometimes but a battle pose, simulated confusion just one more way to lash and thrash. It is only the woefully naïve who can read a philosopher say, “What I really don’t understand is …” and expect what follows to reliably reflect honest confusion. (In this sort of counterfeit confusion, too many philosophers do indeed follow ironic old Socrates, and more’s the pity. He was cleverer than most and at least he had his daemon—we have only each other.)

If sincere uncertainty may be received as but one more salvo in the escalating wars, better, then, to keep it to oneself. So, too, it’s not clear what one would win if one were taken as sincere. For in our online dialogues, to be found uncertain can itself invite contempt. When dialogue is driven by those not only certain of their views but agonistically scornful of those who think otherwise, harboring doubts and reservations is a form of “otherwise”—in failing to agree outright, one might as well be foe…

But we could do better:

The complexities that each could bring to each would have us tarry long and carefully. We could then be better on our guard, not against being called stupid or hateful, but against being so. We would want each other’s reservations and hesitations because these would make us better, not only smarter but more humane.

The full essay is here.

Discussion is welcome, but please do take care not to exhibit here the problems Professor Olberding identifies in her essay. Thank you.

Related: “Commenting Here: Some Advice“; “A Note on Making Discussions Here Better“; “Comments Policy“

There is much to agree with here. Thankfully, there are some who do well in these online discussions. The most prominent, to my mind, is David Wallace (with whom, by the way, I disagree about a lot). Thank you, David Wallace, for exhibiting some of our most important virtues!

Thank you; I really appreciate that.

You’re welcome!

The truest DN comment in living memory!

This works at a meta-level too. People who express with certainty that philosophers need to be more charitable toward those who exhibit uncertainty are taken to be the enemy, even if they agree outright with the particular Groupthink claims du jour. The only really safe position to hold is that the claims du jour are entirely correct, and that anyone who would undermine them by suggesting it is OK for people to question them is actually an enemy of all that is good. It’s the same way religious indoctrination works. Doubt is considered sin. (Mind you, some religious approaches avoid this pitfall by encouraging questioning, and good on them).

If some of you disagree with me or doubt my conclusions, by all means, you’re welcome to it. I don’t think you’re the enemy. I want to listen to your reasons and I hope we can understand each other.

Important article but also seems to run together a couple of potentially distinct things. There’s appropriate appreciation of complexity and uncertainty, then there’s intense substantive argumentation, and then there’s what I took the piece to mostly be about from its examples: illicit rhetorical or ad hom moves (“assailing the basic competence and intelligence of one’s opponent or assailing her moral scruples and humanity”). I only bring it up because we should probably be eschewing the latter things generally regardless of intensity or uncertainty.