The Underproduction of Philosophy PhDs (guest post by Daniel Hicks)

The following is a guest post* by Daniel Hicks (UC Davis), in which he explains how it could be that, contrary to conventional wisdom, there aren’t enough people getting PhDs in philosophy.

The Underproduction of Philosophy PhDs

by Daniel Hicks

One common explanation for the continuing structural employment problem for philosophy PhDs is that there are “too many” philosophy PhDs. That is, according to this explanation, the supply of philosophy PhDs (i.e., the number of new PhDs) is greater than the demand (specifically, the need for people with PhDs in philosophy to teach philosophy classes). One way to empirically check this explanation is to look at the tenure-track employment rate—what fraction of recent philosophy PhDs are employed as tenure-track faculty? Insofar as this rate has gone down and remains low, this suggests that the field has been overproducing PhDs.

But this empirical check ignores the phenomenon of casualization or adjunctification. That is, instead of hiring tenure-track faculty to teach, colleges and universities have hired adjuncts and other contingent faculty. Given this phenomenon, the number of new tenure-track positions in philosophy doesn’t necessarily reflect changes in the demand for philosophy teachers. So the tenure-track employment rate is not a good measure.

A more accurate way to measure demand for philosophy teachers would be based on total student enrollments in philosophy courses. However, as far as I know these data aren’t publicly available, either nationally or for individual schools. I suggest the number of bachelor’s degrees in philosophy could be a useful proxy for total course enrollments. These data are publicly available from IPEDS. This assumes that the ratio of philosophy majors to total enrollments in philosophy courses is roughly constant. But, given that assumption, changes in the ratio of new BAs to new PhDs can give us a sense of whether philosophy has recently been producing “too many” PhDs. Specifically, if this ratio is much lower today than it was, say, 25-30 years ago, then this is an indicator that the field has overproduced PhDs.

In fact, the opposite appears to be the case. Over the last 15 years, the bachelors:PhD ratio was elevated, suggesting that the field has underproduced PhDs. This is not the case in all fields.

For comparison, in this post I examine electrical engineering, English, biology, mathematics and statistics, physical science, and sociology, as well as philosophy. I use IPEDS data from 1984 through 2016. As of December 15, 2017, the IPEDS data for 2016 are provisional. I use simple sums to calculate the number of bachelor’s degrees and PhDs in these fields in each year. This produces slightly higher numbers than Eric Schwitzgebel reports in this post using the same data; usually the difference is 50 bachelor’s degrees or fewer. Since Schwitzgebel does not fully document his methods, I can’t tell where this discrepancy comes from.

The complete code to reproduce this post—including data retrieval—is available here. If you find errors in the code, please submit them as issues on GitHub or email me directly at [email protected].

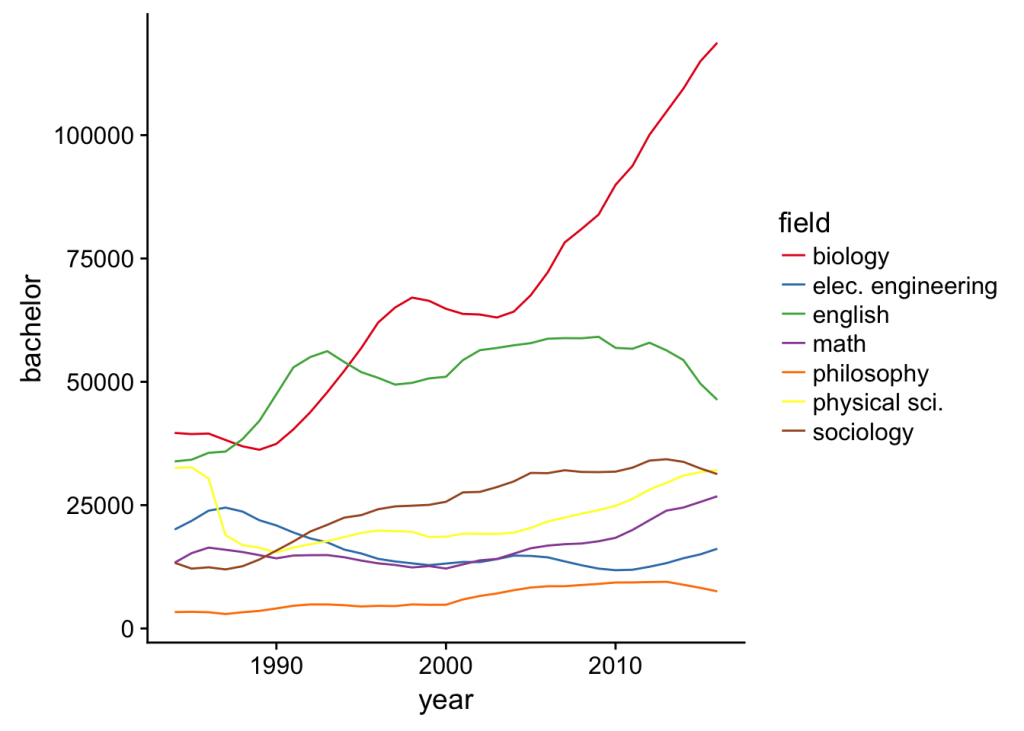

The first plot below shows the total number of bachelors degrees, by field and year. The plot shows a dramatic rise in biology; a sharp drop-off in physical science in the 1980s, followed by a gradual increase; and more-or-less stable numbers across the other fields.

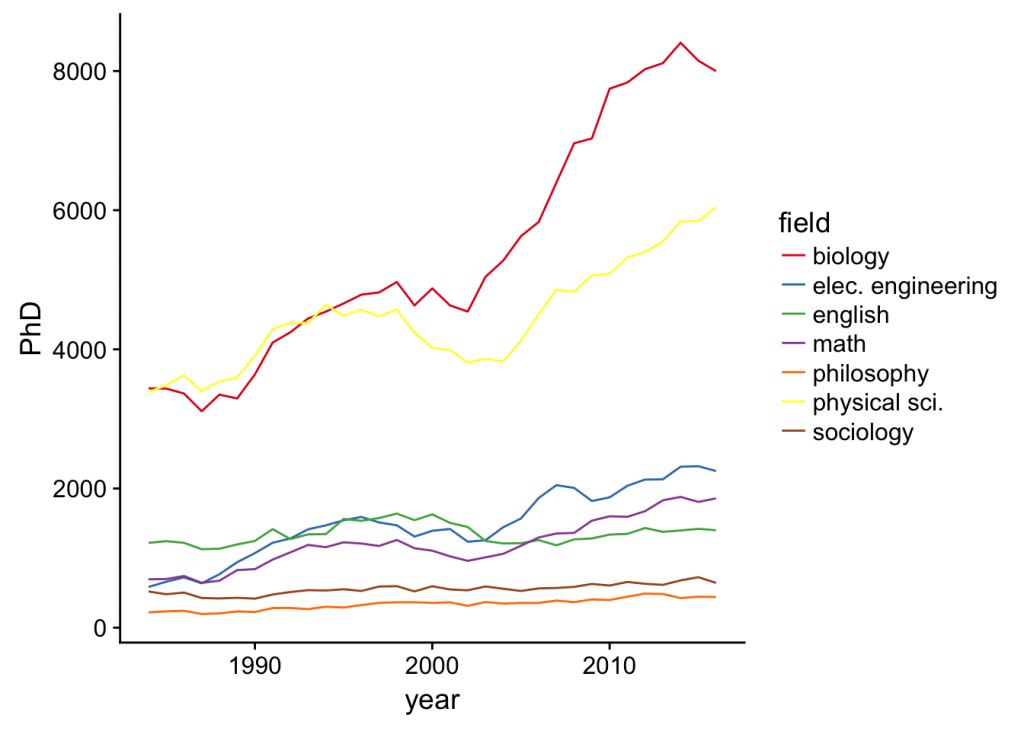

Next we plot total PhDs. Again, there is a dramatic rise in biology, and smaller increasing trends for most other fields. Physical science is much more prominent in this plot than in the bachelors plot.

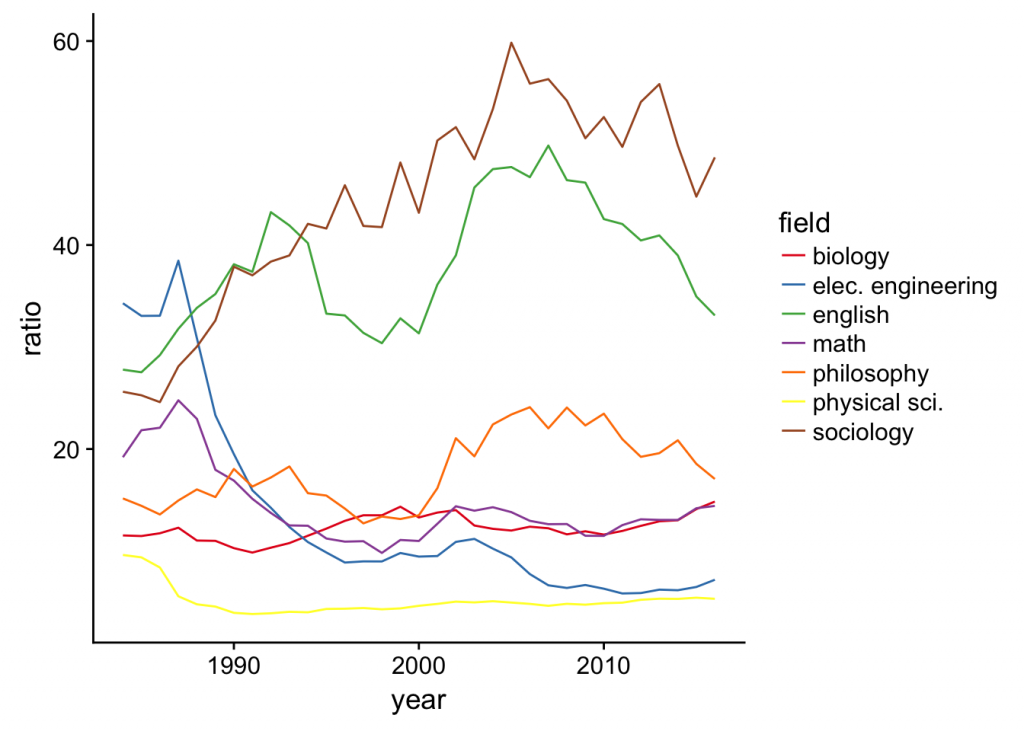

Now we move on to the ratio of new bachelors degrees to new PhDs. Again, we are using bachelors degrees as a proxy for the total demand for philosophy teachers. Comparing this ratio for recent years (the right-hand side) to 25+ years ago (the left-hand side) gives us an indication of whether these fields have been overproducing or underproducing PhDs. If the ratio is lower today than 30 years ago, this suggests that supply (PhDs) has increased relative to demand (bachelors), and so the field has been overproducing PhDs. But if the ratio is higher today than 30 years ago, this suggests that demand has increased relative to supply, and so the field has been underproducing PhDs.

Working from top to bottom, the long-term trends for sociology and (to a lesser extent) English is an increasing ratio. This suggests that these fields have been underproducing PhDs. This story is somewhat more complicated for English, which shows large peaks and troughs.

In contrast, electrical engineering and math had decreasing ratios in the first 15 years of the data, and recently have been more-or-less flat. Physical science follows a similar but more mild pattern. This suggests that these fields overproduced PhDs.

Philosophy shows a cyclical pattern, similar to English. During roughly 2002-2010, philosophy’s ratio was higher than during 1985-2000, suggesting that the field underproduced PhDs. The ratio has decreased slightly in the last few years, and today appears to be roughly where it was in the early 1990s.

Finally, the ratio for biology has been nearly flat. While the number of PhDs in biology increased dramatically over the last 20 years, so did the number of bachelors degrees.

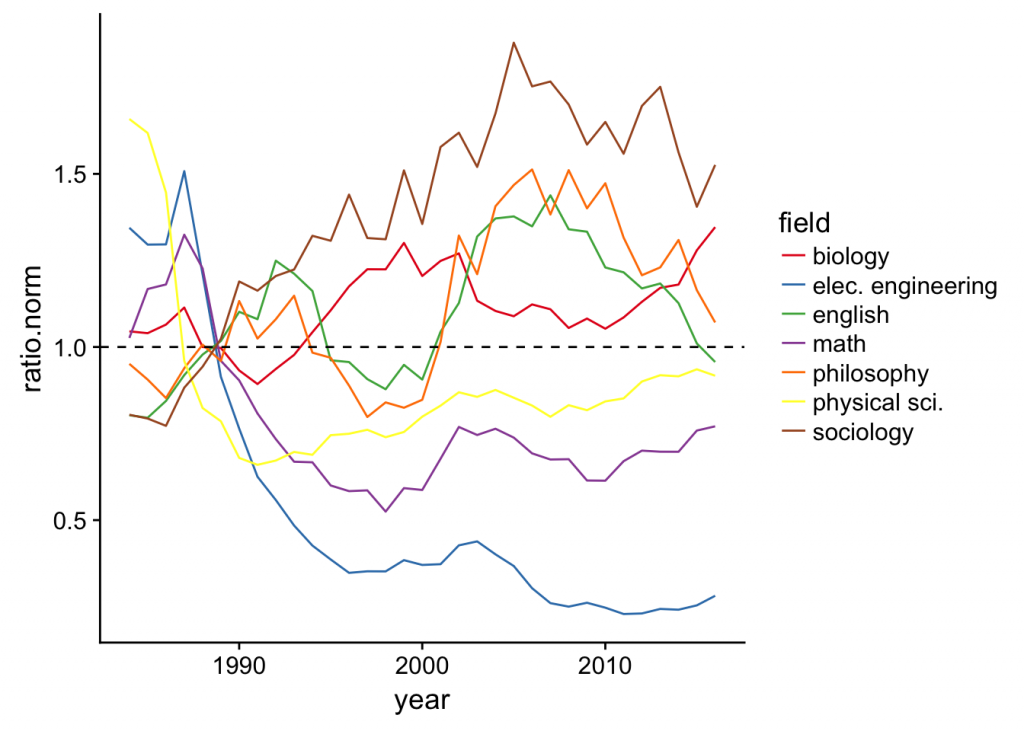

Because the ratios for different disciplines are on different scales, it may be easier to interpret a normalized ratio. In the following plot, for each field, we first calculate the mean ratio over the first ten years of the data (1984-1994), then divide the ratio in a given year by this mean.

As with the previous graph, if this normalized ratio is high—above the dashed line at 1.0—that suggests that the field has underproduced PhDs. This appears to be the case for sociology, philosophy, English, and biology; although philosophy has increased only slightly relative to the 1984-1994 baseline, and English has recently dropped just below this baseline. There appears to be chronic overproduction in physical science, math, and electrical engineering.

So, against the common explanation for the structural unemployment problem, this analysis suggests that philosophy (along with English, biology, and sociology) has produced too few PhDs, rather than too many. This suggests, I think, that the right way to address the structural unemployment problem is to focus on de-adjunctification—that is, pushing colleges and universities to turn short-term, part-time teaching contracts into long-term, full-time teaching positions, and to turn long-term, full-time teaching positions into tenure-track faculty positions. This push is likely to be most effective by organizing strong faculty, adjunct, and graduate student unions. But that is a topic for another post.

Related posts:

“Against Reducing the Number of Philosophy PhDs”

“Are There Too Many Philosophy PhDs? It’s Complicated“

The premise that the number of bachelor degrees in philosophy is an accurate indicator of total enrollment in philosophy courses is probably false. In my experience majors make up only a small proportion of total enrollment in all but higher level ‘seminar’ style courses.

I had this concern as well, however, the more I thought about it (and I admit I am no statistician) the more reasonable it seemed; the claim is not that the only people taking philosophy courses are majors, since this is demonstrably false, but rather that the number of majors correlates with the number of people taking the classes. This may also be false, but I don’t think we have the data to say conclusively.

There is no philosophy major at the community college where I teach, but this doesn’t mean that no one is taking philosophy. We would have to do some more research to determine if there is a correlation on a wider scale, however.

I tend to give the author the benefit of the doubt in this case, though I wonder to what extent I do that because his conclusions are consistent with my own agenda.

This article ignores the fact that course caps and course loads continue to rise. I teach more students and more courses than I did three years ago. In fact, our department lost two full-time faculty members last year, a senior professor and a lecturer, and we will likely never receive new lines to replace either one. Nevertheless, our number of majors and enrollments are increasing.

This article fails to take into account is the administrative fetishism of efficiency. They want more work out of fewer people even if it sacrifices quality. This is true in English, as well, my wife’s department. So, the analysis just doesn’t work.

The solution may indeed be to push colleges and universities to hire more full-time and tenure track philosophers…good luck with that. We have been trying for years. It isn’t going to happen for us anytime soon.

I’m not sure these things are ignored (though they are not explicitly mentioned to be sure) and in any case they seem to support the author’s claims, and if I’m reading you correctly, you’re at least generally sympathetic to his conclusion.

Larger classes and heavier course loads are one way to respond to increased demand for philosophy teaching without increasing the number of philosophy teachers. In terms of the bachelors:PhD ratio, this would mean that the “correct” ratio would be higher. In economics jargon, this would be called increasing “worker productivity,” and it does look more economically efficient. So yes, this is one possibility that my post doesn’t explicitly take into account. I assume that “worker productivity” of philosophy teachers has remained constant.

But that criticism assumes the quality of the “products” is the same; in other words, that students who take a 50-person bioethics course from a more harried teacher are getting an education just as good as students who took a 20-person bioethics course from a teacher with more time to give individual feedback. I suspect the two are not equivalent.

In fields such as bio, phys, and electrical engineering, it seems strange to suggest that an increasing/decreasing trend over the last few decades in the bachelor:PhD ratio is grounds for thinking that PhDs are being under/overproduced in these fields. Presumably, the job market outside the University is an important factor to consider, and this seems (I assume) to be even more true for bio, phys, and electrical engineering than the other fields mentioned.

I don’t see a really credible argument that the PhD/bachelor ratio is a reliable proxy for “demand,” particularly when you’re comparing to fields with a laboratory/applied science component that requires more one-on-one teaching. There is also the simple fact that engineering, natural, and formal faculty tend to pay their own salaries through outside funding a lot more than philosophers. The problem with philosophy PhDs remains demand, not supply, and the argument that in a perfect world demand should be high is not a good reason to further increase supply.

This may just be a tangent, but I’m curious: how do these numbers account for the effects of philosophy program elimination, often justified by the decrease in majors in the context of overall under-enrollment and under-endowment at the schools in which it occurs?

Relating these trend lines seems dubious. If nothing else, why shouldn’t an administrator look at the rise and fall of those ratios as a justification for hiring adjuncts? After all, what is to say an increase in philosophy majors is a lasting trend or one of the bubbles shown in the ratios? And bear in mind that there is a gap of about 7 years between the time a PhD student starts in the doctoral program and then finishes the degree shown in the second trend line, followed by another 4 to 6 years between the time that PhD emerges on the job market and an undergraduate receives one of the philosophy degrees shown in the first trend line. There are a lot of variables between those data points, with no clear evidence that faculty contingency is the link. To the contrary, the most recent survey of philosophy departments found relatively low levels of contingent faculty (per http://bit.ly/2x117ri ).

Yes. it would be great if we had more tenure track professor lines. World peace would be neat as well. It is not as though the suggestion: “Let’s get more tenure track philosophy professors” is one that we all haven’t agreed with and have been trying to make happen for years. It isn’t happening. In addition, to know if there are too many philosophy PhDs, all we need to know is if the demand for philosophy teachers is being met. It is being met. So it seems we have enough. Let’s not make this more complicated than it is. Lastly, for those who are not going to end up with a tenure track position and only teach in adjunct positions, it would probably make more sense for their well-being to only go with a MA.

This entire post likely uses the wrong data points for its proxies.

Academic disciplines differ widely in the number of new PhDs who enter into the non-academic workforce, so that’s a poor measure to examine academic employment. It’s also likely the case that patterns in new bachelors degrees influence patterns in new PhDs issued, since one partially feeds into the other.

A more appropriate measure is to look at the Occupational Employment Survey and figure out how many people are actually working as faculty in given fields, then compare that to bachelor’s degrees issued. I don’t have philosophy’s stats nearby at the moment, but I do know that ratio for English explains the dismal English job market very well. Specifically, in 2000 there were about 50K English faculty and just under 50K English bachelors degrees issued per year…or almost a 1:1 ratio. Today, there are about 75K English faculty, yet English bachelors degrees have dropped to 44K per year. Their faculty hiring over the intervening years far outpaced student demand for English degrees. So now we have an English PhD glut.

Unfortunately, the OES lumps philosophy and religion together, so it does not quite compare. (The trends can be found at http://bit.ly/2yUxgye ). In the context of this report, their numbers also do not differentiate between full- and part-time faculty, so the growth could merely reflect an increase in adjunct employees.

“So, against the common explanation for the structural unemployment problem, this analysis suggests that philosophy (along with English, biology, and sociology) has produced too few PhDs, rather than too many.”

OK, so amend the explanation then: structural unemployment is a problem because the field is overproducing PhDs, GIVEN the constraints imposed by the absurdly powerful administrative-industrial complex. I think this is a much more charitable reading of what everyone is thinking.

So the political question is: do we live with these constraints, or fight them? Notice that this is a high-stakes question: if you continue to admit lots of PhDs and lose the fight against the admins, you’ve wrecked a lot of young lives and derailed a lot of careers. So, in my view, in order for this post to evade a serious objection to its content–an ethical objection–this next post had better have one HECK of a plan for getting universities to de-adjunctify. That post is coming, right?

I’m sorry, that final question wasn’t rhetorical. I want to know if the author is planning to tell us what the de-adjunctification plan is. If not, I want to emphasize that he is playing cute statistical games with people’s lives, and this is plainly ethically reprehensible. These aren’t just numbers, every “PhD” counted in a spreadsheet or database is a person. I can’t think of a positive moral theory according to which it wouldn’t be seriously wrong to admit more of them without a corresponding employment plan.

The post ignores the fact that the (over)supply of PhDs *contributes* to the trend towards contingentization (not just adjunctification). Institutions are able to staff philosophy courses with contingent faculty in part because there is a large supply of cheap labor–qualified people who are willing to accept the wages and conditions of such positions and who are in no position to bargain for better.

I don’t think you’re wrong, of course, but adjunctification and contingentisation are rampant across disciplines.

Isn’t it a leap to say that having a lower ratio of PhDs to Bachelor’s degree relative to the baseline of the 1980s implies an underproduction of PhDs? I thought that casualization and some overproduction of PhDs started in the 1980s so using that as a baseline is really problematic. A change in ratio (even if it was a good proxy) doesn’t say anything about the appropriateness of the baseline. You can’t argue that having more X relative to Y implies that we have too few Y without saying why the beginning ratio was good or balanced.

It’s a fair point. Unfortunately, IPEDS began in 1984, and I don’t know of any comparable, easy-to-access dataset that goes back earlier.

The OP wrote:

This suggests, I think, that the right way to address the structural unemployment problem is to focus on de-adjunctification—that is, pushing colleges and universities to turn short-term, part-time teaching contracts into long-term, full-time teaching positions, and to turn long-term, full-time teaching positions into tenure-track faculty positions.

= = =

This reflects a breathtaking ignorance of what is going on at the overwhelming majority of institutions of higher education. There is zero chance of this happening at my institution or at any others like ours — i.e. unranked, largely undistinguished public universities and community colleges.

Others have explained why using majors as an indication of demand for philosophy makes no sense. Most philosophy is taught in general education. At our university it’s more than 10-1.

Hicks’s analysis is roughly confirmed by another method for analyzing the question of PhD overproduction. The question is whether the number of PhDs explains the poor employment prospects, or whether other (political and economic) factors are needed. The upshot is that numbers alone do not explain the academic employment “market.”

(1) Start with the total number of FTE philosophy positions (in the US). Available data from the Department of Education may only be aggregated by field for humanities. There are maybe 120,000 FTE humanities positions in the US, maybe more. That’s a bit of a guess. Perhaps a better estimate can be made using available data. https://www.humanitiesindicators.org/content/indicatordoc.aspx?i=10

(2) Take the number of PhDs produced in the US annually. This data also are incomplete. But humanities production is around 5500, and of these about 83% (using the NSF numbers, it’s 4531), get academic employment. https://nsf.gov/statistics/2016/nsf16300/data-tables.cfm (Tables 12 and 46)

(3) Then the (idealized) turnover is 1 out of 26 annually. In other words, the current employment and PhD productivity would support a 26-year full-time career for every humanities PhD working in US academia.

Taking the data on PhD production and FTE employment alone does not explain the bad bargaining position of academic employees. I suppose we want enough jobs to support a 30-year career for every PhD who wants one. But 26 years isn’t bad.

The numbers of jobs and PhD production leave out many political and economic factors. *All* US employees are in a bad bargaining position. The explanation for *all* of us is likely to do with the political conditions of employment, not so much the numbers of jobs and available employees. That’s the point of this kind of analysis.

Similarly, truck drivers are still needed as much as ever, yet their wages are falling. The inference: probably the reason is declining bargaining power. https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2017/05/23/trucking-and-blue-collar-woes/

Thanks for the interesting post, Daniel! I’m not sure why you’re getting slightly higher numbers, but it seems like we should figure that out. Are you limiting the data to US universities only? Are you using 38.01 as the code for major? Unfortunately, my programming skills are about 30 years out of date, so I can’t follow your code.

I’m downloading the data files directly from the IPEDS site, and as far as I know IPEDS only includes US schools. Is that incorrect? And yes, I’m using 38.01 for philosophy. Feel free to email me directly to follow up: [email protected].

I’ll email. IPEDS actually has a function on their site to limit the results to US schools, which does exclude some schools. So my guess is that’s the difference.

Wait a minute. The first two paragraphs seem to express something like the following argument (in the most charitable form I can come up with):

1. Many people think that the reduction in tenure-track hiring is evidence for decreased demand for philosophy PhDs.

2. But merely observing the reduction in tenure-track hiring doesn’t capture the whole picture, because there has also been an increase in adjuncts and such.

3. So it’s possible that there’s demand for philosophy PhDs that’s being met by adjuncts, rather than tenure-track professors—a reduction in tenure-track demand doesn’t necessarily mean a reduction in overall demand.

This argument seems seriously confused in a way that highlights difficulties with talk about “demand for PhDs” in general. And that is this: PhDs aren’t the product. The product is some package of teaching and research (and, I guess, service). PhDs are the thing that the sellers of teaching/research/maybe-service packages themselves demand, in order to enable them to sell their teaching/research/maybe-service.

If adjuncts are replacing tenure-track professors, then this suggests that perhaps the demand for teaching is stable (or perhaps it isn’t—this data about bachelor’s degrees downsteream in the post might shed light there), but the demand for research is decreasing.

If that’s true, then the decline in tenure-track jobs is evidence that the demand for people who hold PhDs is also decreasing, by the following reasoning: If an average person who has a tenure-track job and a PhD works for some constant number of hours, C, and is obliged to divide that time into N hours of teaching and M hours of research, then when universities drop research (by replacing tenure-track folks with adjuncts), they can get a full C hours of teaching out an adjunct. (Or they can hire multiple part-time folks and get N hours out of each of them, at the cost of a tenure-track person or lower—which amounts to the same idea.)

And from that, it follows that universities that desire a constant amount of teaching would be able, by switching to adjuncts, to hire fewer PhD holders to teach a constant number of students.

None of this speaks to the demand for PhDs themselves—because, as I noted at the top of the comment, that doesn’t make sense, except when we’re speaking about the people who go to graduate school to acquire them. It might suggest that the demand for PhD-holders is decreasing, however, and hence that graduate students are over-acquiring them.

This is helpful. It does not commit the Econ 101 fallacy by taking the “job market” at face value. Yes, it’s true (in my experience) that department chairs mostly want to put someone with minimally acceptable credentials in front of a classroom. On the other hand, Professor Gowder merely assumes that the product being sold is *not* PhD-holders.

How and what determines what the product is? Are academics themselves are capable of regulating this in some way that better serves the common good?

One proposal for self-regulation is to constrain PhD production. Hicks’s analysis suggests that is not the only possible response, since the number of PhDs is not the only, or even the main factor. I agree.

Many professions regulate who is allowed to practice. Not only doctors and lawyers. Librarians (I’m one) jealously set and apply their own credential standard for who counts as a librarian. Librarians defend librarian jobs for librarians. Librarians are not more powerful than philosophy professors. (I’ve been both.)

It is plausible that academia forfeits the ability to regulate who practices by already allowing graduate student teaching assistants to teach introductory courses (as I did, poorly, a long time ago). Other factors prevent academia from this form of self-regulation, such as lack of adequate institutions. Unions are a kind of institution that would make a difference (I once tried to organize an adjunct union) for truck drivers as well as for teachers.

I read the title of this post and just started laughing out loud. Man!!!!! I had to check if it was April 1st.

If there were not enough PhDs to meet demand, there wouldn’t be adjunct jobs. The value of a PhD would be much higher, and universities would have to pay more to compete for the few PhDs available.

We have adjunct jobs, because there are more PhDs than are in demand. The value of a PhD is thus lower. Universities can then easily *get away* with paying PhDs less and giving them worse jobs.

This is more or less basic economics. Decrease the number of PhDs and adjunct jobs will go away.

This seems perhaps an oversimplification of the complex market forces involved in academic hiring scenarios. I think it reductionistic to suggest that adjunctification is merely the result of a supply/demand curve. There’s a whole lot more involved, not the least of which are declining social capital of scholarship among the broader citizenship and attacks on academia (and intellectuals generally) in popular (and thereby political) discourse.

The declining social capital of scholarship affects demand for PhDs. The problem in academia is that the supply of PhDs has been increasing at the same time as demand has been decreasing. Certain factors affect the demand curve; other factors affect the supply curve. No doubt the demand curve has been negatively affected by the fruitcake liberal nonsense coming out of our universities. It has also been negatively affected by the neoliberal, ‘conservative’ nonsense coming out of Washington (and apparently every other western government), where the solution to structural economic problems is austerity to support the rentier class. On the supply-side, we are fighting the motivational structure of universities (the more students the better), a poor job market causing students to stay in school, and an overall higher education bubble.

What a hilariously stupid blogpost. This post alone is why PhDs in philosophy are no longer in demand. They know less than an economics 101 student.

I bet you could have expressed 99% of what you wanted to say, Jerry, while being 100% less of an asshole about it.

You’re right. My apologies.

Is this article a joke?

Demand for philosophy PhDs and other similar humanities degree are arguably academia-driven. Few folks care about a philosophy PhD (or a Victorian English PhD, or an Art History PhD) unless you’re teaching it or working in a very specialized field.

The opposite is true for most of the putatively-“overproduced” fields. PhDs in psychology and sociology; biology; chemistry; and physics act like professional certifications and are widely relied on in the real world. Most biology PhDs are working at places like Pfizer, or in hospitals. Most psychologhy PhDs are working as psychologists.

How on earth could the author ignore that?

If we take your claims as given, can you elaborate how that impacts the argument of the article?