The Intellectual Achievement of Creating Questions

A commonly recognized form of intellectual achievement is the correct answering of questions. This kind of achievement is not a matter of mere quantity—one doesn’t get much credit for answering easy questions or trivial ones—but also quality. What counts is providing answers that add to the store of human understanding, understood broadly.

When I’ve asked people, informally, which academic disciplines are particularly representative of intellectual achievement, in the sense that the people working in the discipline have accomplished a lot, the top answers have been physics, biology, and computer science.

These are disciplines that can be characterized as taking up questions that are important to advancing our theoretical and practical understanding, for example: What kind of stuff is the universe made of? How does that stuff behave? What can we do with this stuff? How did we come into existence? How do our bodies work? How can we fix our bodies when they are not working as we’d like? How can we use technology to make our tasks easier? How can we use technology to answer our questions? And so on.

Furthermore, these disciplines are good at answering their questions. We can look at the history of their inquiries and see improvements in their methods and in the justifiability of their answers. We see convergence on both methodological and substantive consensuses. Further, some of their answers have informed the creation of effective practices (e.g., medicine) and tools (e.g., computers), which provide further justification for their answers.

On this understanding of intellectual achievement—the “correct answers” version—how does philosophy do?

Let me preface my answer by saying to my fellow philosophers, I love you (in the sense in which one can love a large group of people most of whom one doesn’t even know—and I love you in part because you make me feel like I have to include this clarification; also, philosophers, I find you frustrating for that very same reason; dammit, I seem to be getting off-message now). And I love philosophy.

That said, I think the answer to “how does philosophy do at providing correct answers to philosophical questions?” is terribly. There may be some overly clever ways of denying this but most of you know what I mean.

For support, consider the well-known lack of consensus on answers to philosophical questions (for example, see the entire history of philosophy; also, the PhilPapers survey data). According to Michael Dummett, “It is obvious that philosophers will never reach agreement.”

It is not unheard of to hear this related complaint about philosophy’s stagnation: we’ve been working on the same questions for 2000 years.

I want to believe, with Derek Parfit, about the youth of certain branches of philosophy, and leverage that into optimism about the whole endeavor. But we have about as much inductive evidence as one could reasonably hope for that, as an intellectual endeavor aimed at providing true answers to good questions, philosophy is a failure.

The more I think about it, the more I am surprised at how little impact this failure has on what philosophers do, or how they understand what they are doing when they do philosophy.

Many philosophers see philosophy as a truth-seeking enterprise, and see its value in that. David Chalmers, who, both in virtue of his intellectual interests and his co-leadership of PhilPapers, has perhaps a more informed view of the discipline than most, says:

I think a case can be made that attaining the truth is the primary aim at least of many parts of philosophy, such as analytic philosophy. After all, most philosophy, or at least most analytic philosophy, consists in putting forward theses as true and arguing for their truth. I suspect that for the majority of philosophers, the primary motivation in doing philosophy is to figure out the truth about the relevant subject areas: What is the relation between mind and body? What is the nature of reality and how can we know about it? Certainly this is the primary motivation in my own case. (p.11)

Widespread disagreement among philosophers over answers to these questions, and even over the methods by which to approach them, should make us skeptical that philosophy is really about figuring out true answers to them.

My love of philosophy and my love and respect for philosophers has motivated me to try to make sense—in a charitable, positive way—of why there are still people going into philosophy, or continuing with it, despite its apparent ill fit with its practitioners’ ostensive goals. These are smart, interesting, and creative people. They’ve made philosophy their lives’ work. Start with the assumption that this decision makes sense and work backwards: what explains it?

The money? The fame? The power? No, no, no.

Just that they’re good at it? No, not just that—that fails at charity.

That philosophy is fun? Maybe, but that probably isn’t the the whole story for most philosophers.

Philosophers generally see philosophy as a worthwhile form of intellectual achievement. We can be right about this if there is an alternative understanding of intellectual achievement that fits better with philosophy.

So here is one form of intellectual achievement according to which philosophy does well—even though it is one that philosophers themselves do not typically emphasize: the creation of questions.

It’s actually misleading to say that philosophers have been working on the same questions for 2000 years. It is true that there are some questions philosophers have been working on for that long, but it is also true that there are more philosophical questions being studied today than ever before—because what philosophers have been doing all this time is creating questions. And when these are interesting and important questions, their creation, along with the hints we can provide about how to try to go about thinking about them, should be understood as intellectual achievements.

There are at least four (non-exclusive) kinds of question-creation going on in philosophy:

- Reinvention – bringing attention to a forgotten or neglected question by asking it in a new way.

- Application – reformulating a version of a known philosophical question so as to apply it to a new domain and in doing so bringing new considerations into play.

- Specification – showing that a known philosophical question is ambiguous or incomplete by making relevant distinctions and articulating the other questions whose answers are needed in order to clarify or complete the first one.

- Inauguration – asking a question that creates a new area of philosophical inquiry

Creating good philosophical questions takes knowledge, skill, ingenuity, and hard work. It is usually difficult. So it fits with a familiar understanding of achievement.

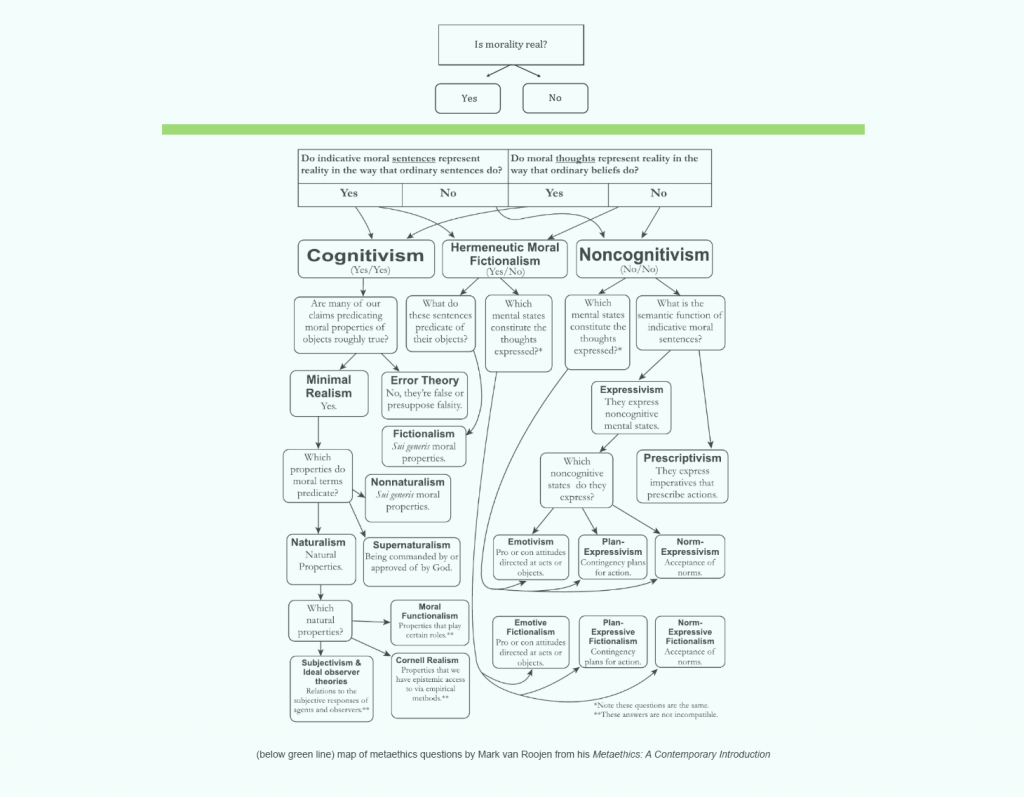

Above the green line: a basic question about the nature of morality. Below the green line: how philosophers refine and create/discover the questions that arise in addressing the basic question.

Why is it worthwhile? For one thing, the questions are interesting! Second, formally, if the answers to questions are valuable, then the questions, insofar as they led to the answers, are themselves at least instrumentally valuable in that way. Third, insofar as people value something like philosophical thinking, the creation of these questions is valuable insofar as they help structure and encourage such thinking. Fourth, unanswered questions indicate what we do not know. So insofar as knowledge of what we do not know is valuable—which it is, in various ways—such questions are valuable. Fifth, answered questions are valuable insofar as they provide examples and guidance for further inquiry.

Additionally, the idea that creating questions is an intellectual achievement is bolstered by an explanation often given for philosophy’s lack of progress, what Chalmers calls “disciplinary speciation”:

many new disciplines have sprung forth from philosophy over the years: physics, psychology, logic, linguistics, economics, and so on. In each case, these fields have sprung forth as tools have been developed to address questions more precisely and more decisively. The key thesis is that when we develop methods for conclusively answering philosophical questions, those methods come to constitute a new field and the questions are no longer deemed philosophical. (p.21)

If the disciplinary speciation account is part of the truth about our intellectual history, then, if the other disciplines that have emerged from initially philosophical questions are of value, then the creation of the questions that prompted their emergence are thereby valuable.

I’m not saying that the only way in which philosophy is an intellectual achievement is in its creation of questions. I’m just saying that it is truly excellent in this respect, and further that this is a valuable type of intellectual achievement. (I also recognize that some philosophical questions are themselves also answers to other philosophical questions, but leave aside that border skirmish here.)

Of course, the idea that the value or importance of philosophy lies with its creation and posing of questions should not be all that unfamiliar, as it is akin to how Socrates understood the value of what he was doing.

Yet I do not often hear philosophers today describe the value or importance of philosophical work in these terms; rather, many philosophers understand a significant portion of the value of what they are doing as trying to figure out the true answers to philosophical questions. They emphasize that in their research, and works that offer answers seem more highly esteemed in the profession, and seem more prevalent in public-facing venues, than works that create questions.

In short, by emphasizing answers, we are promoting an understanding of intellectual achievement that devalues philosophy, rather than an understanding of intellectual achievement that can make sense of why what we do is worthwhile and significant.

That strikes me as odd and unfortunate.

To help counter this, I am proposing a project for us to take up: a timeline of the creation of questions in the history of philosophy.

I think this would be a wonderful resource for the profession to have—interesting in itself, but also of use in demonstrating the richness, diversity, value, and magnitude of what philosophy has achieved.

This post is based on a section of a paper I gave at the Rocky Mountain Ethics Congress earlier this month.

“To help counter this, I am proposing a project for us to take up: a timeline of the creation of questions in the history of philosophy.”

This is an interesting proposal, it sort of is a research programme that can be pursued as a proof of concept.

It seems like this might serve to vindicate the choice of ‘great philosophers’ that we emphasize if they were particularly good at reframing debates to find new questions.

If we want to think about these things paradigmaticly, one could say that while science is a paradigm of knowledge, I’ve often pondered about philosophy as a paradigm of doubt.

But I think there is something Interesting to be aquired from this perspective. Let’s consider (in the Kuhnian sense) that the paradigm of science undergoes *shifts*. It seems appropriate in that this would be the case as we typically understand knowing to be monistic. If you know one thing, it’s inverse can’t also be true. But doubt is pluralistic, such that you can doubt both a thesis and it’s antithesis, even if you understand that one of them must be true. So the paradigm of philosophy, in the sense that it can be understood as doubt, does not *shift*, but just continues to expand. As an aside; while science does not want to shift, it wants to get things correct eventually, if we think of art as a paradigm, it is motivated by it’s shift, where it’s substance is defined by it’s process (of shifting).

Of course, a paradigm of doubt is only one way of understanding philosophy and is probably insufficient under critical scrutiny.

Steven Sverdlik has a very interesting paper that traces the history of the punishing-the-innocent objection to utilitarianism. Maybe objections aren’t exactly questions, but I imagine the legwork that goes into the research will look pretty similar.

Sverdlik, Steven. 2012. “The Origins of ‘The Objection,'” History of Philosophy Quarterly 29.1. (2012): 79-101.

There’s lot of progress and question-answering if you recognize which questions are answered. Philosophy is good at analyzing, thus answering questions about, proposed answers to deep questions, but not good at determining which proposal is the correct one. For example, while there’s no consensus about the nature of truth (deflation, correspondence, relatively), we have now several worked-out theories, and in inside each theory there’s normal intellectual progress. (What follows from what, what are useful axioms, what is (in)compatible with the theory, etc.) I propose we better compare philosophy to mathematics than to physics. In math, it’s no use asking whether spherical, hyperbolic or whatever geometry is the true geometry. Each is studied in its own right.

If philosophy is not about finding the correct theory, then why do philosophers argue for their theories? Why are there arguments for and against each theory? Why care about the costs and benefits of the theories? Shouldn’t philosophers stop arguing and just focus on creating as many logically consistent theories as possible?

“If philosophy is not about finding the correct theory, then why do philosophers argue for their theories? Why are there arguments for and against each theory?”

To get tenure?

it tends to be argued that philosophies are not theories. Therefore, the premise of your argument here, maybe unsound.

About twenty years ago I was lucky enough to be included in an in-service training course for teachers at a private school in Thailand, although at that point I was primarily the IT tech. The course was held at the Thai equivalent of a community college and most of it I’ve forgotten, but one thing about the course has stayed with me. The Thai education system is often criticized for relying too much on rote memorization, but one of the Thai teachers there impressed me — maybe I should say astounded me — with the excellence of the questions she asked. This is the mark of a truly great teacher, although I’ll bet it’s completely overlooked in American schools now with the unthinking emphasis on scores on “standardized” tests. As we were explaining our points, she invariably asked one or two questions that required a complete re-thinking of what we were saying. I asked her about it afterward, and she was just truly curious and wanted to learn more. That is what is so hard to instill in students.

There is a large research project at the University of Oslo that seems closely realted to your ideas: http://www.hf.uio.no/ifikk/english/research/projects/cl/

Why create questions that cannot be answered? Shouldn’t we focus on creating questions that can be answered?

If a question cannot be answered, then we should forget about the question, no matter how “interesting” it seems. Endless speculation and intuition mongering will just waste valuable resources that would be better spent elsewhere.

“Fourth, unanswered questions indicate what we do not know. So insofar as knowledge of what we do not know is valuable—which it is, in various ways—such questions are valuable.”

I don’t see much value in knowing that we don’t know whether, say, mereological nihilism or the trope theory are correct. It is enough to know that we generally don’t have metaphysical knowledge. This is of course a matter of taste but I think the world would have been a better place if these theories and the questions that they provide answers for would never have been developed.

“Third, insofar as people value something like philosophical thinking, the creation of these questions is valuable insofar as they help structure and encourage such thinking.”

Theoretical questions in science encourage similar thinking AND can lead to new positive knowledge. Shouldn’t we focus on them instead?

Maybe have a look at this: https://philosophyofquestions.com