Philosophy PhDs Worthless According To Proposed Immigration Point System

“Had I received this job offer under the newly proposed plan for immigration reform endorsed by President Trump, I’d have been deported back to Canada.”

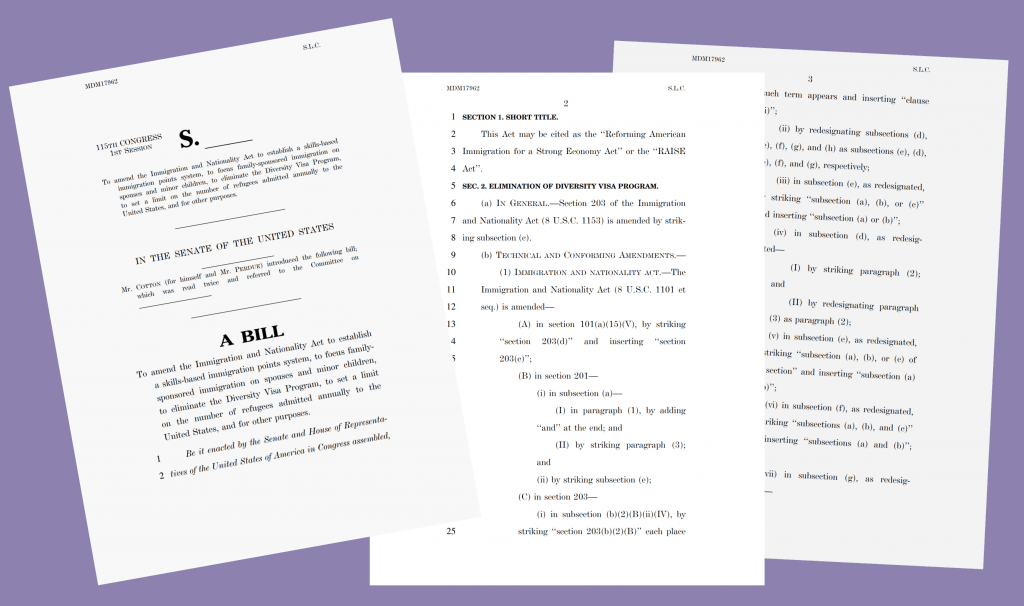

So writes Carol Hay, associate professor of philosophy at University of Massachusetts, Lowell, in yesterday’s The Stone column in The New York Times, in regard to a bill aimed at restricting legal immigration, sponsored by Republican Senators Tom Cotton (Arkansas) and David Perdue (Georgia). It operates on a point system.

Professor Hay continues:

I wouldn’t have passed muster. My main problem? I’m a philosopher. Receiving an Olympic medal is enough to bump you to the front of the line, but receiving a Ph.D. from a top ranked American university isn’t—unless it happens to be in a STEM field. Because I work in a discipline in the humanities, my American doctorate is worthless.

The essay can be read in full here.

Isn’t it reasonable for an immigration system to consider the expertise that the country is lacking as an important part of its criteria for selecting immigrants?

If the US has a huge surplus of PhDs in philosophy, are there any good reasons for allowing even more to enter the country?

There is an argument that the points system should include provision for truly exceptional candidates, but it is likely that it does already (other countries certainly do).

Why isn’t this just reason to let them in but not let them work in philosophy?

Why? Most countries want immigrants to fill specific gaps in the labor market. Immigration rules aren’t for the general benefit of foreigners who want to live in the US.

It’s weird to read some posters saying this means their degrees are being described as “worthless”. It’s not a comment on the worth of a degree, but on the demand for the degree in the job market – one specific property of their degree.

This seems like a prime example of people (like politicians) not understanding the value that philosophers add to the academy. BUT, I don’t think politicians (or others) are to blame for this misunderstanding. Philosophers (on the whole, in my experience) do a terrible job of explaining why philosophy is important. Hay’s article is an example. Rather than explain why philosophy should be valued on a par with STEM fields, she gives the written equivalent of the incredulous stare. And that kind of attitude is never going to convince people that philosophers are a valuable component of the academy (I’ll restrict this to philosophy because I’m not entirely sure that the humanities as a whole DO constitute a valuable addition to the academy; but that’s just my opinion).

It’s not just that our advanced degrees are worthless (although that’s bad enough) this system simply reduces merit to money.

For example, even leaving aside any philosophical accomplishments, being first author on a technical paper published in a NASA journal, the government’s chief technical representative on a $300 million dollar contract negotiation for intelligence satellite software, AND a professor who teaches philosophy of science at one the US Military Academies (a required class for science majors) doesn’t even garner the ability *to be considered* as a potential immigrant. You can’t even apply.

Now, if you make more than $160,000 or have $2 Million to invest, you’re fine without any actual technical expertise, but even if merit were only technical merit, merit is neither necessary nor sufficient.

I doubt that Philosophy PhDs are “worthless” here because the people that came up with this system thought to themselves “we already have a glut of Philosophy PhDs, it would be irresponsible to let more in.” The proposed system makes any non-STEM higher degree worthless. Honestly, to me it looks pretty antagonistic towards higher education in general — what this system likes is people who have capital, or who have skills that (they assume) can be converted into capital really easily. (Although, I’m surprised to note that MBAs are also apparently worthless?)

I, for one, am not surprised to learn that MBAs are apparently worthless.

Agreed. I am not surprised either that MBAs are apparently worthless, as it has always been my opinion that they actually are near worthless.

The good news is that I’m in with a score of 37.

I have a STEM PhD (as designated by ICE), plus a masters and JD, and I don’t qualify either.

To seriously debate the Trump administration on this point is to give it too much credit.

It irks me that Hay’s article in the NYT as well as the title of this blog post makes it seems as if there is something about the discipline of philosophy in particular which is being singled out in this proposed immigration point system, when rather, it is ANY and ALL non-STEM graduate degrees which are grouped into the same “worthless” category as concerns immigrants. A picture is being painted which is a little misleading. Nobody is attacking philosophy in particular.

That being said, I do think its a mistake that non-STEM doctorates are not considered at all in determining one’s value as an immigrant to the United States. I completely support the idea of accepting immigrants which are highly likely to bring value to the country, and the form of that value can and is up for debate. But I think whatever the answer, certainly a doctorate in a non-STEM discipline must count for something as far as determining a candidate’s level of education. That a foreign historian for example gets no merit for having attained the highest graduate degree possible, making him/her an expert in their field, is absurd.

I don’t have any brief to defend RAISE but isn’t Professor Hay confusing conditions for immigration with conditions for non-immigrant work visas? I thought most non-US-citizens came into the US on a non-immigrant H1B? In which case Professor Hay is wrong to say that she wouldn’t have been able to take up the job under RAISE, though it would constrain her longer-term plans. (Happy to be corrected, I’m not that familiar with how this works in the US.)

I think H1B visa has a limit for the duration of work time (6 years). After 6 years, one has to leave the country for a year in order to reapply for another H1B visa. So far as I know, many people use H1B to work at first and then apply for green card. So, if the point system is a hard line for green card, I think it will be irrational to give a tenure-track position to one who is neither American citizen nor a permanent resident. (And those who hold academic positions in the US but are not at least permanent residents will also be forced to leave, which I guess will create more open positions.)

Of course this only applies to those foreigners who will not score at least 30 points in the system. But as professor Hay points out, it means most (if not all) of them.

If the job market is terrible for US academics–in humanities, let’s say–that could at least be a prima facie reason to exlcude competition. Doesn’t Canada have preferential hiring for Canadians, so this is just the inverse of that? And it doesn’t bar foreign humanities PhDs from non-academic jobs; the salary dimension can let them in (e.g., into publishing houses or whatever). Not obvious why mere fact of PhD should lead to obvious entitlement to immigrate into some country.

Also, if Jason can get a 37 and the author couldn’t get a 25, it’s clearly not *only* the PhD that’s doing the work; maybe everyone should just be more like Jason (e.g., in the abstract–though he’s lovely in person, too).

Jason Brennan teaches at a business school, and business schools play much higher salaries than do humanities departments, especially humanities departments in non-flagship schools. That’s surely a big part of his higher score. Business schools don’t have higher intellectual standards, though (if anything, they are typically a bit lower, though not so much as most philosophers are likely to suppose) and it’s not clear that they contribute more to the good of society. Furthermore, in either case the person will be a net-contributor (will pay more in taxes than will use in services, on average) and so this is, if anything, an argument against the policy.

Canada does have a policy of preferential hiring for Canadians in academia. My impression is that the top Canadian schools manage to avoid this, for the clear reason that not doing so would be to their serious detriment. (Artificially limiting your hiring pool is almost never a good idea.) It’s not a general policy, like this is, but a sort of protectionist policy for Canadian academics. My view is that it’s a pretty dumb and arguably immoral policy that works to the over-all detriment of Canadians, as protectionist policies usually do, but even if that’s so, it’s not that relevant in evaluating whether this particular policy is a bad one. Insofar as it can be understood at all (it’s really unclear in the details – I’ve been following discussion among other immigration professionals, and the thing is, unsurprisingly, poorly drafted and a bit of a mess) it’s pretty bad, and would almost certainly be a net negative for the US unless you put a really high premium on keeping out foreigners.

Let’s be clear: like Canada, the US has preferential hiring policies in place that require university employers to demonstrate that they couldn’t find a better domestic hire for a position requiring VISA sponsorship. It’s the same all over the world, including in the UK and Australia. That’s pretty much the extent of the hiring law in Canada, it’s just that all job ads feature boilerplate language to that effect, which might make it seem more serious than it is. And just like in the US and elsewhere, it’s really easy for universities to get around that requirement–and they frequently do (it’s not just Toronto/UBC/McGill).

The reason it’s hard for Americans to get jobs in Canada isn’t the hiring law, it’s that it’s hard for *any* academic to get a job in Canada. There are what, five or six TT openings in philosophy across the country (several of which are at Toronto alone) every year? Most Canadian citizens who are on the academic job market will not find a job in Canada, and that’s especially true for philosophy.

Preferential hiring it is not “the same all over the world”. This ridiculous policy certainly is not present in most countries in W Europe, at least those I’m familiar with. Even when academics are public servants, citizenship is not a requirement.

You’re right, it’s not identical all over the world. If you want to read my remark that strongly, I’ll gladly walk it back. Note, however, that citizenship is *not* a requirement (de facto or de jure) for a work permit in Canada, nor in the US. I’m not sure where you got that from. In theory, it’s an advantage; in practice, it’s mostly not, because academic hiring is so narrowly specialized that it’s easy for universities to make the case that there’s no better-suited domestic candidate in their applicant pool.

My point was simply that such policies are not at all rare, and that they’re not necessarily the obstacles they’re often made out to be. The US already has one in place that’s pretty close to Canada’s. And as commenters have pointed out, the entire EU has a similar requirement, since there’s a minimum number of EU nationals who have to be interviewed. Couple that with “cooling off” requirements for consecutive work visas (such as in the UK) and the like, and you’ve got the makings of a similar set of policies. Sure, they’re different, but their goals and mechanisms look analogous to me.

That’s not to say that non-EU nationals don’t get hired, or that they have an especially difficult time on the EU or UK job markets, all things considered (I have no idea whether that’s the case; it’s an empirical question, and I don’t have the data). But that was my point: the same is true of Canada’s policy, and the US’s (again: the current policy, not the proposed immigration changes).

Again, and to be perfectly clear: I am *not* talking about the points-based immigration system that the Trump administration is proposing.

Um, are we seriously considering the ‘prima facie’ merit of the most severe nativist turn in US immigration policy in decades based on the state of the academic job market? Come off it, folks.

RAISE has essentially no chance of getting through the senate. It’s filibusterable and there’s no chance it will get significant Democratic support; more importantly, enough Republican senators support fairly-free movement of labor that it won’t even get a majority (even if those senators might find it politically helpful to blame the filibuster). So discussing it is interesting more as the first steps in a possible conversation about immigration reform than anything else.

There are good reasons someone might want to avoid that conversation: they might be ideologically opposed to any tightening of immigration; they might have a systematic no-engagement policy with the Trump administration (albeit RAISE comes out of the Senate, not the White House). But if you’re either in favor of moving the immigration system to be more skills-based, or more pragmatically would prefer a well-designed skills-based system to a badly-designed one, it makes sense to point out its more specific shortcomings in the hope that future iterations are better designed. (RAISE is clearly pretty badly designed even if you’re in favor of a skills-based pivot, and while some members of congress are probably just using it as a pretext for reducing immigration and don’t care about the details, it’s unlikely in the extreme that they can get it through without support from members of congress who do care.)

‘Michel X says t’s the same all over the world, including in the UK and Australia.’

I may be wrong, since not living in the UK I don’t follow every twist and turn of the Brexit debate, but as I understand it, until March 2019 this isn’t true of the U.K. a (unless by domestic you mean ‘EU citizen’, which would be an odd thing to mean by it right now.) Until then, it remains the case that UK universities are required *not* to have a preference for UK citizens over equally well-qualified applicants from elsewhere in the EU.

“Domestic” exactly means “EU” in this context: that requirement is part of EU law, which requires all EU citizens to be treated equally.. If it sounds odd right now, it’s because the U.K. has said that it is leaving the EU but has not actually done it.

It sounds very odd to say that a requirement to treat (some) non-citizens in a non-discriminatory manner is *just the same* as a requirement to give one’s own citizens priority, as Michel X seemed to be. (And even odder to say that the proposed US policy is ‘just the same’ as the existing EU one.)

It would sound just as odd, to my mind, if this arrangement was going to continue indefinitely rather than (we should probably presume) end in 2019. Using the word ‘domestic’ to mean ‘all EU citizens’ seems to me to obfuscate rather than clarify in this context (though I can

I think there’s been a misunderstanding: I most emphatically did *not* say that the *proposed* US policy is the “just the same” as the existing policy in Canada, the UK, and elsewhere. What I did say was that we shouldn’t make too much of Canada’s preferential hiring policy, because it’s one that’s equivalent to one *currently in place in the US* (and elsewhere), and it has about as much clout (i.e. not that much). It was a small point about hiring policies, not immigration policies.

The idealistic way to think about “EU citizens” is that the EU is a unificatory project, and that in its current iteration everyone is a citizen of the EU as well as of their individual country – and that part of the unificatory project is that rights are defined at an EU rather than an individual-nation level (just as, in the US, they’re mostly defined at a federal rather than a state level).

There’s a more transactional way to think about it, where it’s more like a free trade deal for labor: EU nations mutually agree to give each other’s citizens equal employment rights.

Either way, this is one of the key issues behind Brexit.

Given the current state of political affairs in the United States, I would not consider *visiting* that country, let alone migrate to it. Of course I understand if some academics make different choices, after all the prospect of a well paying job is not something most people would easily pass up on. But the worry that a humanities PhD is insufficiently appreciated in the new immigration rules strikes me a totally oblivious to the mess we, the world, are currently in. The USA are heading for nuclear disaster and apparently purposely accelerating global warming. I’d say that those issues should be the priority before considering the pros and cons of attracting foreign PhDs. Moreover, whining about how you might have been ‘deported’ under the new rules, will not likely impress anyone who needs convincing that the current administration is performing subpar.

Just to be clear, I do not think that all US citizens should lapse into a state of paralysis concerning everything other than the Big Issues. It is specifically the narrow, self-centered focus of US academics expressed here that I find… well, distasteful.

I am a little puzzled as to how criticism of the RAISE act is going to increase the likelihood of nuclear war.

But of course, nowhere did I suggest that. I do suspect, however, that American scholars congratulating themselves on their wittiness have played an important role in the election of Donald Trump.

Anyway, my objection was not against criticism on the RAISE act in general, but, on how this specific reaction expresses a mode of self-absorbed thinking. But maybe you had stopped reading by then.

I’m interested in hearing how American scholars congratulating themselves on their wittiness has played an important role in electing Donald Trump.

Well, I said I suspect and that’s exactly what I meant. I think that those who have the skills to voice their opinion eloquently (and to have that opinion published in, say, the New York Times) in general have a tendency to be rather dismissive of opposing viewpoints, which will more than likely come across to many as inspired by an attitude of smug self-satisfaction. It seems to me that such a perception may do much to fuel divisiveness in an already polarized country. Correct me if I’m wrong, but from what I understood many people who voted for Trump did so out of resentment towards a ‘liberal elite’. The same liberal elite, I suppose, who like to mock and ridicule those who hold an opposing view.

It makes me relieved at the humble attitude I try to take to my own wittiness.

I would like to urge Carol Hay and other privileged nondisabled feminist philosophers to stop publishing articles in The Stone. As I and others have pointed out here and elsewhere on numerous occasions, The Stone systematically excludes work by disabled philosophers on disability. Although disabled people make up the largest minority group in society, disabled philosophers are the most underrepresented group in philosophy. Privileged nondisabled feminist philosophers must do more than they have thus far done to mitigate and eliminate this exclusion in the profession, ,regardless of the venue in which the production of it takes place. There are plenty of other venues in which nondisabled feminist philosophers can make their work available to the public.

I would also like to urge the members of the APA Committee on Public Philosophy to stop conferring prizes upon nondisabled philosophers who publish in The Stone and hence, in effect, rewarding The New York Times for the column that discriminates against us. I would think that the current exclusionary publishing policy of The Stone column in The New York Times goes directly against the organization’s anti-discrimination policies.

The willingness, on the part of nondisabled philosophers, to overlook, disregard, and remain indifferent to the policy of exclusion that The New York Times has instituted with respect to work in philosophy of disability by disabled philosophers seems to be an example of what I call “ableist exceptionism,” whereby political values and beliefs that one assumes and uses in other domains do not have salience when it comes to disability and ableism. I find it hard to imagine that feminist and other philosophers would abide by a policy of exclusion with respect to any other marginalized and subordinated social group or group of philosophers like the one that The New York Times continues to enforce against disabled philosophers.

“The Stone systematically excludes work by disabled philosophers on disability.”

Can you provide some support for this accusation?

Nevermind, I didn’t see the links below.

What makes you think they are systematically excluding this work? There has only been so many articles published, and there are *a lot* of different types of people that have not yet been represented. That does not mean The Stone is excluding them, they just haven’t yet published work by them yet as the weekly article is a limited resource and can only do so much.

http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/2016/01/throwing-stones-at-a-glass-house.html

http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/2016/07/disability-and-the-stone-which-public-whose-philosophy.html

http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/2017/07/david-perry-on-philosophy-disability-and-the-stone.html

http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/2016/12/tipsy-tullivan-and-the-new-york-times.html

I sent these links a while ago, but they seem to have disappeared. Here they are again:

http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/2016/01/throwing-stones-at-a-glass-house.html

http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/2016/07/disability-and-the-stone-which-public-whose-philosophy.html

http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/2017/07/david-perry-on-philosophy-disability-and-the-stone.html

http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/2016/12/tipsy-tullivan-and-the-new-york-times.html

Asked for evidence of systematic discriminatory exclusion you provide links to your own blog posts which assert that there has been systematic discriminatory exclusion. Thanks.