Police Shootings of Blacks in the U.S.; What Can Philosophers Do or Say in Response?

News from the past week:

- July 5th, 2016: Police officer shoots and kills Alton Sterling, a black man, while he was seemingly pinned to the ground, unable to move.

- July 6th, 2016: Police officer shoots and kills Philandro Castile, a black man, after he was pulled over for a broken tail light.

- July 7th, 2016: Five police officers killed by sniper fire during a demonstration against police shootings of blacks.

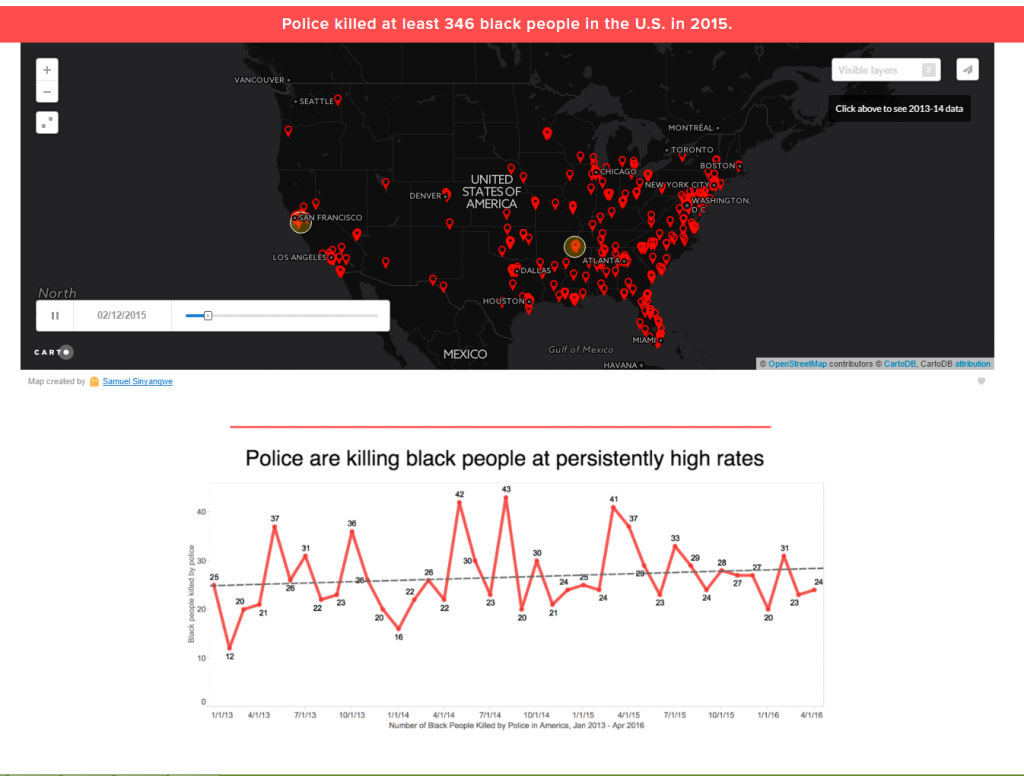

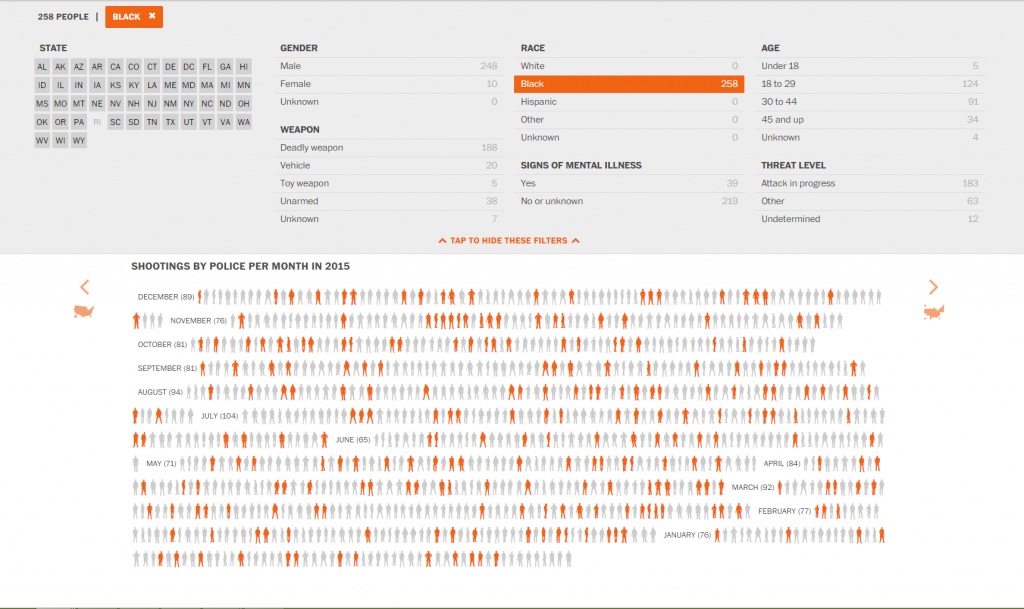

There is some variation in the data, but regardless, the numbers of black people killed by police in the United States are very high, especially in light of the underlying demographics of the country (roughly 72% of the population is white while 13% of the population is black—further demographic data here), and also in comparison to police violence elsewhere in the wealthy Western nations.

Nathan Nobis, a philosopher at Morehouse College, wrote to me following the shooting of Alton Sterling:

In light of the recent murder of another black man in LA, I wonder if you could post something asking what philosophers (and philosophy teachers) can do, or even say, about all this that might make a positive difference. Philosophy obviously thrives on controversial issues, and all these killings seem to uncontroversially wrong and completely unexcusable. Given that, it’s hard, at least for me, to see what to say or do about any of this, other than to say and do what anyone else might do or say, that this is all just awful. Anyway, I hope this makes sense and wonder if you could do something to raise some productive discussion here about what, if anything, philosophers can uniquely do or say to address these evils.

Consider this post an open forum for philosophers to discuss various aspects of these shootings, including the killings of the police officers. Discussion of substantive philosophical issues, or of practical matters regarding teaching and advising, or of anything else you think important to draw attention to in this forum, is welcome. Please post links to related articles, discussions, and resources elsewhere.

Here are a few related items of interest:

- “Curriculum for White Americans to Educate Themselves on Race and Racism—from Ferguson to Charleston“

- Description of and link to the syllabus for “Police Violence and Mass Incarceration,” a course developed by Lisa Guenther (Vanderbilt).

- “Philosophers On The Charleston Massacre,” a previous discussion here of the Ferguson shooting and how it might be approached in a philosophy class, and a previous discussion of police violence and race.

- A discussion of “How Many Police Shootings Are Tragic Mistakes? How Many Can We Tolerate?” by Christian Coons (Bowling Green).

(Note: As per the comments policy, while pseudonymous posting is permitted, no handles may contain the word “anonymous” or “anon.” If not logging in via a social media account, a working and accurate email address is required; email addresses are not publicly displayed.)

The NRA’s statement on the Dallas shooting, as imagined by Samir Chopra (CUNY): https://samirchopra.com/2016/07/08/the-nra-on-the-dallas-shooting/

Here’s an article I wrote last year on police brutality, terrorism, and the difference between “Black Lives Matter” and “All Lives Matter”: http://www.abc.net.au/religion/articles/2015/01/28/4169777.htm

One effort I am pushing, here in Charleston, is to institute ethics committees, run as they are in hospitals, in police departments.

Whats is your progress on that? “We can police ourselves” ?

Overall, the lack of response by philosophers on this issue is embarrassing. The linked syllabi are good places to start. Basic education, an open mind, and a willingness to listen would be other good responses. I’ve found that philosophers, being overwhelmingly non-Black, are as ignorant as most non-Black Americans about anti-Black racism in the U.S, if not much more so. Racism denialism is rampant; every putative instance of racism is immediately given an explanation that does not appeal to racism. This tendency is strong and somewhat puzzling, though I suppose it is likely rooted in the cognitive dissonance non-Blacks experience when they are forced to confront the possibility that they are not self-made creatures, that they have benefited enormously and chronically from being non-Black. Mindfulness of this tendency — and of the potential threat to one’s ego and self-conception that might occur in conversations about racism — could probably go a long way.

For those who prefer detailed and empirically informed analyses, here’s an item of interest:

http://slatestarcodex.com/2014/11/25/race-and-justice-much-more-than-you-wanted-to-know/

This may be empirically informed but the author draws conclusions that are unsupported by the empirical data, and at least sometimes advances the (to my mind quite inadequate) traditional conception of racism as a matter of conscious, hostile attitudes. To wit, “stops are most likely neighborhood-related effects rather than race-related per se, but the neighborhood effects do disproportionately target black people.”

I also have some questions about at least some of the numbers. The author claims that the UCR (which tracks arrest data) and NCVS (which surveys victims) show that blacks are not overpunished for violent crimes. However, a quick look at the reports does not support this general claim. In 2006, the last year I could find NCVS data on the race of offenders, blacks were arrested for 56% of robberies committed (per the UCR), yet only 37% of robbery victims said they were robbed by a black person (per the NCVS). Likewise, blacks were arrested for 34% of aggravated assaults, yet only 24% of victims reported a black assailant. NCVS 2006, Table 40 http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cvus0602.pdf; UCR 2006 Table 43 (http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2006).

“advances the (to my mind quite inadequate) traditional conception of racism as a matter of conscious, hostile attitudes”

A careful read of the post suggests that this is advanced not as a conception of racism but (if at all) as one of racial bias in policing. And this stands to reason: imagine a society with a perfectly just and efficient police force with a perfect track record (all and only offenders are arrested), but where Greens offend twice as often as Blues. Greens will be arrested twice as often as Blues; but this can hardly be attributed to racial bias in policing (perhaps it can be attributed to racial bias in the society at large, but that’s a different question altogether).

“I also have some questions about at least some of the numbers. The author claims that the UCR (which tracks arrest data) and NCVS (which surveys victims) show that blacks are not overpunished for violent crimes. However, a quick look at the reports does not support this general claim”

The total figures are probably more reliable than cherry picking a couple of categories. According to the NCVS, the percentage of all the recorded categories of crimes with a (perceived) white offender was 59.0% and with a (perceived) black offender was 22.4%. According to the UCR (adding together property crime and violent crime, which seems to correspond to the figure measured by the NCVS), 65% of those arrested (for property crime and violent crime, which seems to correspond best to the figure measured by the NCVS) were white and 32% black. So, fair enough, there’s a small disparity. The original claim was that the victimization rate and the arrest rates “closely match[…]”, which doesn’t sound far off to me.

On the empirical issue, I think Scott Alexander relies on Lauritsen and Sampson’s review of the literature, where there is a discussion of the comparison between arrest and NCVS data. I can’t recommend enough that review, which is really excellent. It’s from 1997, but I think the point they made about the comparison between arrest and NCVS data is still valid, even according to the latest data. I found NCVS data about offenders demographics from 2008: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cvus/current/cv0840.pdf. The corresponding arrest data from the FBI are here: https://www2.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2008/data/table_43.html. According to the NCVS data, blacks made up 42% of offenders for robbery, whereas according to the FBI 56.7% of the people arrested for that crime were black. But I think the discrepancy is mostly a result of the fact that, in the NCVS data, a large proportion (21.5%) of the offenders are classified as “Other” or “Not known or not available”, whereas in the FBI data people who are neither white nor black only make up 1.6% of arrests for robbery. If we assign people classified as “Other” and “Not known or not available” in the NCVS data to “white” or “black” in proportion of each group among those who were definitely assigned to either category, we end up with approximately 53.5% of blacks and 46.6% of whites, which is much closer to arrest data from the FBI. Now, this method is hardly ideal for various reasons (e. g. some of the people we end up classifying as “white” or “black” with that method would no doubt have been classified as “American Indian” or “Asian” by the FBI), but I think it’s still much better than a direct comparison with the FBI data.

Philippe, thanks for the 2008 data. It’s a shame that there is so little data, and that it is so hard to find.

As for the numbers, it seems very unlikely that a victim will label a black offender “Other.” If the implicit bias research is at all correct, the opposite will be true. So we should only divvy up the “Unknown” category, which puts a bit more distance between the NCVS and the UCR.

That said, the data is not very good and there’s a lot of noise. More work needs to be done.

Yes, some of the data are really hard to find on the BJS website, it’s really a shame. On the other hand, in my experience, they are happy to help when you send them an email because you can’t find something. As for the point you make, you may be right, but I think it’s hardly obvious. The reason I treated “Other” as “Not known or not available” is because there was really a huge discrepancy between the proportion of offenders classified as “Other” in the NCVS data and the proportion of arrestees classified as neither white nor black in the FBI data (we’re talking about a factor of 6), so I’m not sure what’s going on here. It’s difficult to know without knowing the exact procedure of that part of the NCVS interview. One possibility is that people classified a lot of Hispanics in “Other”, but since the NCVS data don’t include a category for Hispanics, I would be surprised if they didn’t make clear during the interview that white Hispanics should be classified as “White”. However, if that’s what is going on, then you are probably right. I’m just no sure at all that it’s what is going on. Lauritsen and Sampson’s review discuss a lot of other relevant data though. On the other hand, while I see why you talk about the research on implicit bias, I don’t think that research is helpful at all here. I really don’t have time to explain why in more details, so with apologies I will just say that the issue of police shooting is one of the best illustrations of the ecological validity problems which, together with the lack of predictive validity, plague that research.

Here are some discussion of the various racial disparities–but there are many others.

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/crime/2015/08/racial_disparities_in_the_criminal_justice_system_eight_charts_illustrating.html

Some other statistical discussions of incarceration rates and sentencing rates:

http://www.nccdglobal.org/sites/default/files/publication_pdf/created-equal.pdf

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/news/2012/03/13/11351/the-top-10-most-startling-facts-about-people-of-color-and-criminal-justice-in-the-united-states/

https://www.aclu.org/issues/mass-incarceration/racial-disparities-criminal-justice

See page 10 of the following for discussion of racial disparities in juvenile cases that control for offense. See page 15 for disparities in the pretrial process that do not depend on offense.

“…considerable evidence exists from a large body of empirical research that race and ethnicity do play a role in contemporary sentencing practices. Research results generally conclude that the primary determinants of sentencing decisions are legally relevant factors—seriousness of the offense and the offender’s prior criminal record. But studies also show that black and Hispanic offenders (particularly the young, male, or unemployed) are more likely than similar white offenders to be sentenced to prison, to receive longer sentences, and to obtain fewer benefits from departures from sentencing guidelines….”

http://www.asanet.org/sites/default/files/savvy/images/press/docs/pdf/ASARaceCrime.pdf

Any and all work by and related to Dr. George Yancy should be taught in every university.

I use a couple of readings on institutional racism in my Social Advocacy class, but I feel like I’m not doing the topic justice in the discussions I lead. Partly this is because my understanding of IR is still to vague, I think – I don’t fully understand its causes, though I’m sure they’re historically rooted, and its relationship to individual racism. And partly I think the problem is that when trying to look at these readings critically with my students, I’m inadvertently undermining the case for IR, which isn’t what I want to do at all. Plus as a grad student I my overall teaching experience is limited. I’d really appreciate some advice on how I can do a better job teaching my students about IR.

I think you may be right that your understanding is still too vague: the causes and the relationship to individual racism is really central (basically, there technically need not be any individual racism, but the prominent examples are largely the results of explicit historic individual racism).

What kind of criticisms are you discussing when you think you might be undermining the case for it? The case for whether the phenomenon exists? Whether it should be called racism? Whether we should be particularly concerned about it? Something else?

The critical questions I’m asking are things like – is IR rooted in individual racism, is the racist behavior intentional, what’s the mechanism behind the playing out of IR, etc. Because I don’t have a good answer to these questions myself, I feel like I’m undermining the case for the existence of IR. I don’t really have any training in this area – I’m a philosopher of science with an interest in science and values, and that’s how I come to be teaching a class in Social Advocacy. I feel pretty secure in most of the topics that I cover in the course, but this one is a noteworthy exception.

Jason Brennan on shooting police officers: http://bleedingheartlibertarians.com/2016/07/the-fall-out-objection-self-defense-vs-war/

Well, that’s a position one could take. :/

I have to admit the shootings yesterday reminded me of a discussion of the Salaita affair a couple of years ago. One commentator on a notable blog wrote: ‘I would find a black professor’s tweets, post Ferguson, troubling if they included expressions of indifference about whether the rioting there resulted in violence against police officers…’ But another commentator soon responded: ‘I’d find nothing whatsoever problematic about a black professor who expressed indifference about violence toward the cops…’ At the time I found that a particularly jarring position to adopt, but no-one in the subsequent discussion appeared to have any difficulty with it. I understand the complaints of racial injustice that rightly drove the protests in Dallas, but when did we as a profession become so blasé about violence against other human beings?

When did single tweets come to represent “we as a profession”? The violence in Dallas was a tragic, immoral, unjust, but understandable, response to a pervasive and deeply unjust system.

Like ejrd said, single commenters (disagreeing with other commenters!) of course don’t represent “us as a profession.” But philosophers have been offering lesser evil justifications of violence against other human beings for basically as long as we’ve been around, right?

Regardless, I wouldn’t read that comment as defending violence towards cops or even being indifferent about it, though it’s hard to mindread across time and hyperspace. “The police are in danger!” was a common derail around the Ferguson uprising, and in the face of police killing black innocents and so many black protesters putting their bodies on the line, I know I wouldn’t have felt like it was particularly problematic for a black professor to respond by saying “I don’t care about the police.” I think that would be a normal and acceptable emotional response.

I knew WP and ejrd were friends.

Here’s my article “When May We Kill Government Agents? In Defense of Moral Parity” at Social Philosophy and Policy

http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=10293534

Personally, I think we need to teach a clear ethic focused on the value of human life. It’s obvious that teaching mere political correctness does NOT teach this ethic. Most Americans, for instance, would be terrified to say (out loud) the plainly true statement that black men are far more likely to be criminals (per capita) than any other demographic group — despite their being racists. This dynamic, where one avoids telling truths, out of fear, builds resentment in people. So instead of just having racists, we have resentful racists. Not a good combination.

The truth is that the reasons for the criminality of African American men lies largely in racism toward them, and, yes, in cruelly unfair policing. But we can’t get to that truth if we don’t even allow people to state the facts.

When we talk about the value of human life, we sidestep issues of personal danger. Surely a gyspy in 1930s Europe was more likely to rob from you, but this did NOT change her value as a human being in the slightest, nor did it change your duty to assume the best of her. We can recognize likelihoods and come to terms with paranoias and fears without treating our fellow human beings like dirt.

It is going to be important to avoid the traditional trap of preaching to the converted by focusing too hard on writing papers and presenting talks for other like-minded academics.

On the other hand, we can certainly consider raising the issue in classes dealing with politics, ethics, philosophy in general, and critical thinking.

Another thing that we can do is encourage philosophers to publish in venues where they will reach a general audience, as opposed to an academic one. Work that isn’t addressed to other academics in Philosophy isn’t given much respect, but it is the broader public we need to influence. Furthermore, as we reach out to a broader public, we again need to avoid just using venues where we will predominantly preaching to the converted.

As we do raise these issues with our students and the broader public, we must remember to keep philosophical questions front and center, rather than devoting ourselves too exclusively to educating people on the facts. If we can’t find more than one side to a given issue, we should ask ourselves what we are contributing as philosophers by addressing it. Obviously, a philosopher who only educates on the facts has done something good, all else being equal.

On this issue, Heather Mac Donald’s recent book “The War on Cops” is worth reading. She argues that the claims of BLM and other activist groups have been vastly exaggerated (and in some cases are downright lies), and that the proactive data-driven policing that they’re opposed to been instrumental in reducing crime and saving minority lives. Here’s the Amazon link: https://www.amazon.com/War-Cops-Attack-Order-Everyone/dp/1594038759

Philosophy, to me, has always been a work of love and this subject is, my no means, an exception.

An Economy of Violence

https://sacredless.com/2016/07/02/an-economy-of-violence/

of the comments posted thus far, three of them seem to be shameless self-promotion and several others tend to avoid the actual question. that’s philosophy in action ! the bad guys better watch out now !

As nobody has posted this yet, here’s a look at some data that’s been going around the interwebs:

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0141854

From the abstract: “Finally, analysis of police shooting data as a function of county-level predictors suggests that racial bias in police shootings is most likely to emerge in police departments in larger metropolitan counties with low median incomes and a sizable portion of black residents, especially when there is high financial inequality in that county. There is no relationship between county-level racial bias in police shootings and crime rates (even race-specific crime rates), meaning that the racial bias observed in police shootings in this data set is not explainable as a response to local-level crime rates.”

I think one of the notable things to come out of this discussion is that police shootings of African Americans are unequally distributed. There are places with comparable populations to (e.g.) Baltimore in terms of size, SES variables, racial composition, &c, but where the police haven’t shot anyone in years. That suggests that local policies and police culture might play a strong role.

Hey Colin,

Thanks for posting. I agree with you. And since the analysis doesn’t include any data on the encounter rates of different races with the police, we can’t tell precisely what is driving the racial disparities in risk ratios. How much is implicit bias playing a role, for example? And how much do local police strategies like those outlined in the Justice Department’s report on Ferguson contribute to this effect? We can’t tell. As they put it:

“The USPSD does not have information on encounter rates between police and subjects according to ethnicity. As such, the data cannot speak to the relative risk of being shot by a police officer conditional on being encountered by police, and do not give us a direct window into the psychology of the officers who are pulling the triggers. The racial biases and behaviors of officers upon encountering a suspect could clearly be components of the relative risk effects observed in the data, but other social factors could also contribute to the observed patterns in the data. More specifically, heterogeneity in encounter rates between suspects and police as a function of race could play a strong role in the racial biases in shooting rates presented here.”

I’m posting again since this question left open by the Bayesian analysis seems crucially important to reformers. It is also discussed elsewhere in the comments to the original Nous post.

Roughly, reformers might wonder whether they should prioritize improving police training, screening of candidates, etc. Or, should they target the revenue-generating policing laws in cities like Gretna, Ferguson, etc.?

I’ve just read several stories about a certain kind of policing that had dramatic racial implications–it’s been called “revenue-generating policing.”

So, this might be a huge driver behind the relative risk ratios of getting killed while unarmed, even if we could somehow control for both officers’ bias in their lethal encounters and their profiling of black suspects for crimes.

An article in the New York Time came out today on a working paper by the Economist Fryer. It addresses these kinds of issues. The summary claims that he found no racial bias in lethal encounters with the police. But, this claim is based on self-reported data from small number of police departments, so it may be unreliable.

Interestingly, he also used data from the federal government’s survey of civilian encounters with police. Using this data, the estimate he made for racial bias in non-lethal encounters was an entire degree of magnitude higher than his estimate based on the self-reported data from police departments. That’s huge!

Here’s the link: http://mobile.nytimes.com/2016/07/12/upshot/surprising-new-evidence-shows-bias-in-police-use-of-force-but-not-in-shootings.html?smid=fb-nytimes&smtyp=cur&_r=0&referer

I have used Naomi Zack’s book White Privilege and Black Rights: the Injustice of U.S. Police Racial Profiling and Homicide. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015, in my Intro. Ethics class. The response from students (who I am pretty sure were all white–it was an online class) was very positive. They appreciated the the way concepts they’d read about earlier in the course such as justice and equality applied to a contemporary, real-life issue. They were also largely ignorant to the statistics about crime, stop and frisks, and homocides that Zack cites, and very concerned about the deaths of young black men at the hands of police. Since Zack’s book is 100 pages long, it’s not that difficult to insert into an intro. course and it’s pretty accessible.

I honestly believe that philosophers should not respond, at least not in the way politicians, journalists and social media responds, as a knee jerk reaction to an event.

Do what philosophers have always done, identify the real questions and dismiss mistaken apprehensions.

To avoid knee jerk reactions even among philosophers, I need to stress that I KNOW the problem is structural racism.

However, some important questions

1 Is there a distinction between rational fear of a group and irrational fear?

2 (Empirical question). What constitutes the group that is over-represented in police killings. Is it black people, poor people, felons or is there some other characterization of the group?

3 Is reasoning under perceived threat the same as reasoning under secure conditions?

4 Should reasoning under threat be the same as reasoning under secure conditions?

etc.

I agree that my orientation seems to be to try and get into the mind of police officers, but that is because they have the agency here.

I know we will find that the answer points to systemic racism, but I think we will find it has a very different form to that most people assume. Indeed, we will almost certainly conclude that the issue is not police racism but a much deeper and more prevalent racism.

“but that is because they [police officers] have the agency here.”

I can’t imagine what you mean by this that could possibly be true. We all have agency here; police traffic stops or other police encounters don’t happen in a vacuum. Just think about the presuppositions and social conditions necessary to make your (1) – (4) into salient questions. There’s nothing wrong with asking those questions, but it would be both a political and philosophical mistake to think that those are uniquely “the” salient questions, or that police are uniquely “the” agents in this.

Also, until you said so I didn’t realize those questions were meant to be mainly about police officers. They could just as easily be questions about the appropriate attitudes and disposition of black Americans toward encounters with the police.

OK, I actually agree with you. I was thinking of the simplistic fact of where agency lies when the trigger is pulled and understanding that moment.

Look any deeper and there are much broader and more profound assumptions and presuppositions involved and a historicity of events and narrative in which we are all actively involved.

Even so, I would suggest that one approach (but not the only approach) to getting a deeper picture f what is going on is to take a really close look at that mooment when a police officer pulls the trigger on an African American and then considering how that moment was shaped within a much broader, temporally extended and complex perspective

I think that a narrow focus on the moment when a police officer decides whether to pull the trigger on an African American is probably a very bad idea. (And the “reasonable fear” standard is the standard set up in American law that is a virtual get out of jail free pass for police violence–the civilian need pose no actual threat, need have done nothing to indicate that he poses a threat, as long as the police officer has a “reasonable fear” that there is a threat the use of deadly force will be ruled justified. And the standard for “reasonable fear” appears to be “The police officer says the victim reached for his/her waistband and there’s no video evidence disproving it.” See here.)

Anyway, undigresssing–I think analytic philosophers too often focus on individual decisions or individual people in thinking about ethics, and it makes it hard for us to give an account of institutional evil and the like. So I think we shouldn’t focus narrowly on the moment of the police officer’s decision. Instead, we could ask questions like this:

How does it affect people of color when they are unable to interact with the police without fearing for their lives?

What are the consequences for a community of being unable to call the police for assistance, or even to open the door for police, without fear of a shooting?

What are the consequences of being unable to open a door or enter a stairwell in your building without fear of being shot, because the police view your building as so presumptively high-crime that they patrol it with their guns drawn and will pull the trigger in response to any unexplained noise?

How does it affect the right of black people to bear arms when they can be shot by police for legally carrying a weapon, even if they have not threatened anyone or made any move to retrieve their weapon, and are in fact complying with an order from a police officer when they were shot? Is a right really a right if you can be shot for exercising it?

Who should bear more risk of being shot without justification in an encounter–a police officer, who has voluntarily taken a dangerous job with the responsibility of enforcing the law and protecting innocent civiilans, or a civilian, who has not voluntarily a position of danger and often is at risk of death in an encounter simply because of his or her skin color? Does police training or practice lead to an appropriate distribution of risk?

Does police training in use of force reflect a realistic assessment of risks, or does it train the police to use force indiscriminately?

Why do other countries have so many fewer killings by police? Is there anything we could do in our police training, etc., to be more like those countries?

I think we should start with questions like this, because if we look at the broader institutional context for five seconds, it becomes clear that the current situation is insupportable. Then we can ask the question of what we need to do to change police officers’ decisions in the moment. Focusing first on that moment puts the cart before the horse.

Sorry, my whole name didn’t autocomplete there–that comment is by me, Matt Weiner.

Excellent comment. Thanks. I especially appreciate the way you point out the narrow temporal focus on the action and the state of mind of the officer at the time. We could compare Stand Your Ground laws, which, if I understand the issue correctly, encode a similarly narrow temporal focus on the immediate action by removing the previously customary “duty to retreat.”

And I also appreciate the way this narrowing of focus to the mental state immediately preceding an action fits into bad philosophical habits.

for those just catching up on the Philando Castile case (one of the two case that allegedly motivated the sniper in Dallas), an overview: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/stopped-52-times-by-police-was-it-racial-profiling/2016/07/09/81fe882a-4595-11e6-a76d-3550dba926ac_story.html

To address the question in the title of the OP, “what can philosophers do?”, I think the answer is — for most of us — “nothing”. If this is your area of specialization, if you work in ethics or philosophy of race or maybe social/political philosophy more generally, then you may have something to offer.

But there is no reason to think that logicians, metaphysicians, philosophers of mathematics, epistemologists, etc. have anything special to offer. Maybe insofar as they’re generally intelligent people they could contribute something. I don’t, however, see any reason to think that philosophers as a group have anything to offer qua philosophers.

Perhaps I’m wrong. I’ve always found it a bit odd, though, that many seem to hold some presumption that we, as philosophers, have something special to contribute to the discussion of issues of great social import. I don’t think Chemists should be expect to have some special contribution, and likewise (most) philosophers are equally ill-prepared to productively contribute.

philosophers have general training in philosophy

Of course not all specialists will have something to offer. But at least some epistemologists, philosophers of mind, and philosophers of language will have something they might contribute. E.g., given how much interest there currently is in peer disagreement, one might think that there would be some interest in disagreement when peers have unequal information, as when Black Americans consistently testify that they are targets of frequent and hostile interactions with police. The rational response from non-Blacks in response to such reports is an interesting question. Epistemic injustice and testimony are also relevant issues here.

And (some) philosophers of mind and psychology could contribute to an understanding of the mechanisms that ground police violence, e.g., weapon bias is a phenomenon that warrants further work, as does implicit bias in general and the social psychological mechanisms that explain how hierarchies can influence interactions between police chiefs and their officers and between officers and the civilians they are meant to protect.

In phil languge, work on generics could be useful, insofar as generics best capture the contents of stereotypes. Generics aren’t, it turns out, very similar in their truth conditions to mere statistical claims, (e.g., “philosophers are men” and “most philosophers are men” turn out to have very different truth-conditions), and this fact has very important ramifications for the (ir-)rationality of stereotypes and for some of their pernicious effects.

I’m sure there are other areas in M&E that are potentially relevant, but those are just a few examples.

I’ve got to agree with Postdoc here, but also say that I think this actually isn’t as strong of a response as is necessary to Merely Possible Philosopher. Not only are there lots and lots of ways in which philosophy outside of social/political philosophy CAN be relevant for racial/social justice issues, I think this also HAS to be the case. That is, we should be deeply, deeply disturbed about our discipline if it had nothing to add to such discussions. As Merely Possible Philosopher rightly said, chemists most likely have little to add to such discussions as well. This needn’t be so disturbing to them, though, because spending time on their work is justified in other ways (e.g. they discover new facts, contribute to new technologies, etc.). We philosophers have no such justification at our disposal. We sit around, think, read, and talk for a living. Especially for those of us who work at public institutions, this should make justifying our work to the general public a high priority.

Now, just because we need to justify our work to the general public, it doesn’t immediately follow that we would need to justify it in terms of contributions to social justice discussions. That said, there are a number of reasons I think these should be high on our list. First, I think that matters of oppression and discrimination are simply the most pressing global issues of our day. So, this would just be a good place to start period. Besides that, though, it does seem to me that are facts specific to the nature of philosophy that make it so it would be problematic if we couldn’t contribute to improving such issues. Philosophy seems to be the place that we work out issues of our general conceptual frameworks. That our inherited conceptual frameworks on race, gender, sexuality, etc. contribute to implicit and structural bias/oppression seems quite clear. Philosophy also seems to be the place that we ask certain kinds of questions that are just taken for granted/ignored by large segments of the population. In my experience, white people are taught that they needn’t critically reflect on any questions related to race relations or racial literacy, generally. Many philosophers have also held that language is essential to what we do in philosophy. Furthermore, language is a social phenomenon. This would seem to suggest that the realm of the social is of particular importance to philosophy. So, breakdowns of the social—like social injustice—should be particularly important to philosophy.

All of that said, I do understand that there’s a very legitimate worry that most philosophers are not specialists with respect to social justice issues of any kind. This just means that we need to be very careful in how we decide to discuss these issues. I think this is doable, though. That is, I think there are clearly ways to stick within one’s area of philosophical expertise (even if that area is M&E, logic, etc.) and still contribute to discussions on racial and social justice. And, frankly, if we CAN do this, why would we not? To put my money where my mouth is and to shamelessly promote myself, the following video is one such attempt of mine to do so (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m3NwQR0GwdI).

What about if you are a logician or a philosopher of math?

I think this can be done even if one is a logician or philosopher of mathematics. With logic, there can be connections between racial/social justice issues and either deductive or non-deductive forms of reasoning. With induction, there are very strong connections between hasty generalization, confirmation bias, prejudice, and stereotypes. With deduction, there are strong connections between consistency, hypocrisy, and differential treatment. Since there are strong connections between logic and the philosophy of mathematics, there’s room for overlap here as well. That said, I do think things get more difficult when trying to connect the philosophy of mathematics to issues of racial/social justice. Of course, insofar as almost any philosophy class has a historical element to it, there’s always room for discussion of racial/social justice issues. Standard tellings of the history of philosophy are extremely Eurocentric. Disrupt this. Follow Bharath Vallabha’s advice and “Get beyond the same old line up of the great philosophers from the last century to emulate. Find new heros. Create new heroes.” In philosophy of mathematics, see what happens when you add Al-Kindi to discussions on infinity. Discuss the context in which Lambert Quadrilaterals and Saccheri Quadrilaterals came to be so-called despite the fact that ibn al-Haytham and Omar Khayyam studied them first. When you read Frege’s Grundlagen, have a discussion on his claim from page 1 that “In arithmetic, if only because many of its methods and concepts originated in India, it has been the tradition to reason less strictly than in geometry, which was in the main developed by the Greeks”. Ask if Frege is on to something here or if there might be some insidious assumptions leading to such a statement (which will hopefully involve investigating what various Indians were able to contribute to the study of arithmetic).

We can expand on the question “What can philosophers do?” in two ways.

First, “What would the most famous 20th century philosophers have done in response to the police shootings of blacks? Say, Quine, Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Rorty, Lewis, and so on?” The question isn’t, “What implications could one draw from their philosophies to the racial situation in America?” One can draw any number of implications from philosophies understood as abstract ideas. The question instead is, what would these thinkers as people, as living philosophers have done? It’s not clear what the biographical answer to that is. Quine, Wittgenstein, Heidegger – they lived through times of colonialism and end of colonialism, and of segregation in America – but none of that made it into their general thinking. So if they didn’t talk publically and philosophically about that, it is hard to know what they would say about the current situation.

Second, “Beyond what these famous 20th century philosopher would do, would the public listen to them?” Imagine Quine or Davidson going into the public sphere to talk about the racial tensions in the country, and trying to show a path of healing? Even philosophers critical of academic philosophy such as Wittgenstein and Rorty, what would happen if they went into a black community to grieve with them, or to grieve with a lower middle class white family? Would these thinkers help heal, or would it just be incredibly awkward, suggesting these thinkers had no idea how to bring philosophy truly to the everyday world? These philosophers, great as they are in certain contexts, just never developed some skills most ordinary people associate with philosophy.

What can current philosophers do? Get beyond the same old line up of the great philosophers from the last century to emulate. Find new heros. Create new heroes. Be new heroes. Take what is great in these thinkers of the last century, or last half century, but push beyond them, see their limits, and live beyond them. We are living in a world already so different from what Quine and Wittgenstein lived in. Current philosophers should allow themselves the freedom to move beyond the halos of these thinkers and create new role models for new times.

Jackson and I try to tackle some of these issues. We take a personalist look at the issues.

http://ow.ly/rGHf302982c

I have worked with some here and I recall there was no real interest in the critical philosophy of race, but I am glad you are working on it now. We’ve been working on it in the field for several decades and for me personally it has been the past decade. Interested parties might consider the brilliant work already being done in the critical philosophy of race the past ten years. For example, the edited and scholarly work of George Yancy. His ‘Black Bodies/White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America’ was published almost ten years ago now. It is a highly rigorous and systematic, phenomenological study of race and the issues in the critical philosophy of race.

We’ve been making animated videos about race the past year and half at Wireless Philosophy. Here is the link: http://www.wi-phi.com/front/Political-Philosophy